This is the latest post for an ongoing media project — SoCal Sports History 101: The Prime Numbers from 00 to 99 that Uniformly, Uniquely and Unapologetically Reveal The Narrative of Our Region’s Athletic Heritage. Pick a number and highlight an athlete — person, place or thing — most obviously connected to it by fame and fortune, someone who isn’t so obvious, and then take a deeper dive into the most interesting story tied to it. It’s a combination of star power, achievement, longevity, notoriety, and, above all, what makes that athlete so Southern California. Quirkiness and notoriety factor in. And it should open itself to more discussion and debate — which is what sports is best at doing.

The most obvious choices for No. 99:

= Wayne Gretzky, Los Angeles Kings

= Aaron Donald, Los Angeles Rams

= Manny Ramirez, Los Angeles Dodgers

The not-so-obvious choices for No. 99:

= Hyun Jin Ryu, Los Angeles Dodgers

= Denis Bouanga, LAFC

The most interesting story for No. 99:

Charlie Sheen, as Ricky “Wild Thing” Vaughn, Cleveland Indians relief pitcher (1989) in the movie “Major League.”

Southern California map pinpoints:

Santa Monica, Malibu, Hollywood

Carlos Estévez, Charlie Sheen and Ricky Vaughn walk into a bar …

The hope is at least one of them comes out alive.

This also seems to add up to more than just two-and-a-half men. The algebra and physics are far more complicated.

Carlos Estévez, as known to his friends when he grew up playing in Malibu Little League, the Pony-Colt transition, and then on the Santa Monica High baseball team, was good ol’ Charlie. His true center.

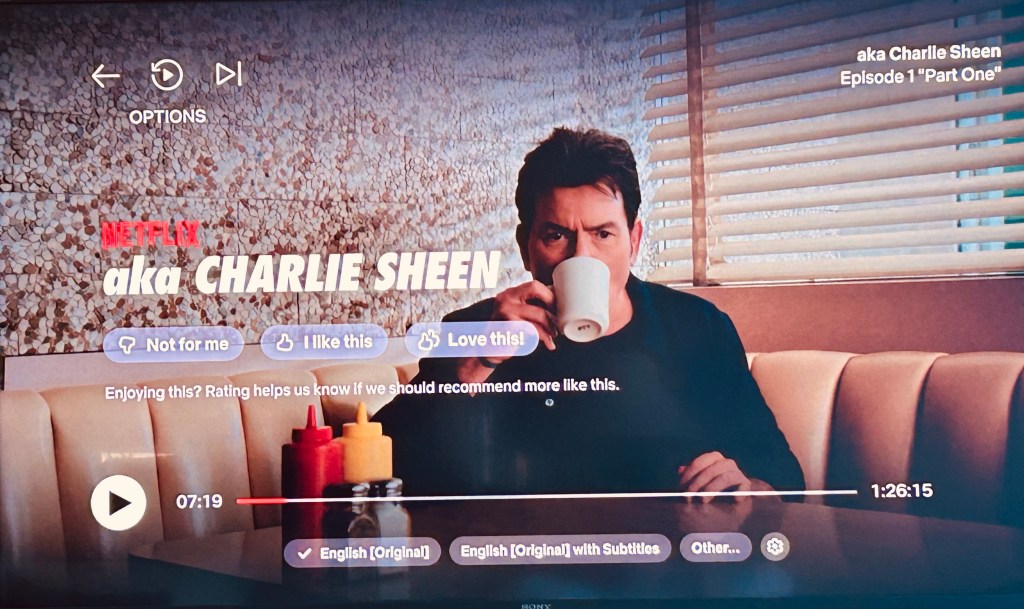

Charlie Sheen is the Hollywood flip-side, best explained in a 2025 Netflix documentary appropriately titled, “aka Charlie Sheen.” Good time Charlie. You know him to some degree, and then you don’t.

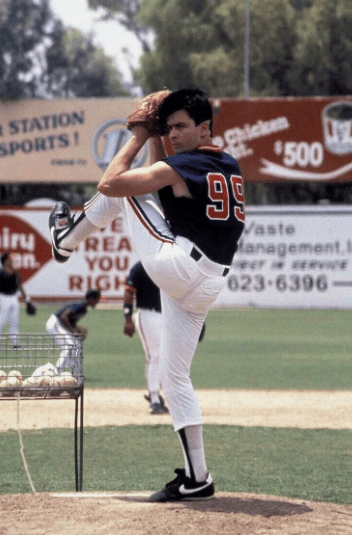

Ricky Vaughn, a role Sheen played as the steel-focused wild-child relief pitcher in the 1989 film “Major League,” amplified his Hollywood persona. It would have a notable ripple effect within the culture of Major League Baseball bullpens. Art reflecting life reflecting relief artists. All the way down to wearing No. 99 for some psychological advantage when staring down a tepid hitter in the late innings.

Meanwhile, there is an art to understanding this “concept” of the Estévez/Sheen/Vaughn triumvirate.

“I think there’s so many stories and many ingrained images in people’s minds about the concept of me,” Sheen says in the documentary, sipping something from a coffee cup while seated in a booth at Chips Restaurant, one of the last iconic Googie diners across the street from a Catholic church in Hawthorne where Sheen is making his confession.

“(People don’t even) think of me as a person. They think of me as a concept or a specific moment in time.”

As this SoCal sports project hits the far end of numbers — starting at 00 and ending here — it seems obvous we found our closer. Ricky “Wild Thing” Vaughn is called in to provide the Hollywood ending.

Charlie “Wild Man” Estévez/Sheen will get credit for the save. A tip of the coffee cup for those in his circle who’ve saved him time after time.

Grab a beverage and we’ll see where it leads.

Baseball is the connective tissue ultimately in the Estévez/Sheen/Vaughn concept. It become evident sorting through film, TV, tabloids, depositions, affidavits and general convoluted hearsay. Whenever Estévez/Sheen needed the serenity, security and sweet spot of baseball, troubles became secondary.

There’s the famous Jim Bouton quote: “You spend a good piece of your life gripping a baseball and in the end it turns out that it was the other way around all the time.”

Estévez/Sheen might relate to that in a different way.

It’s through baseball where Estevez found his true best friend, Tony Todd.

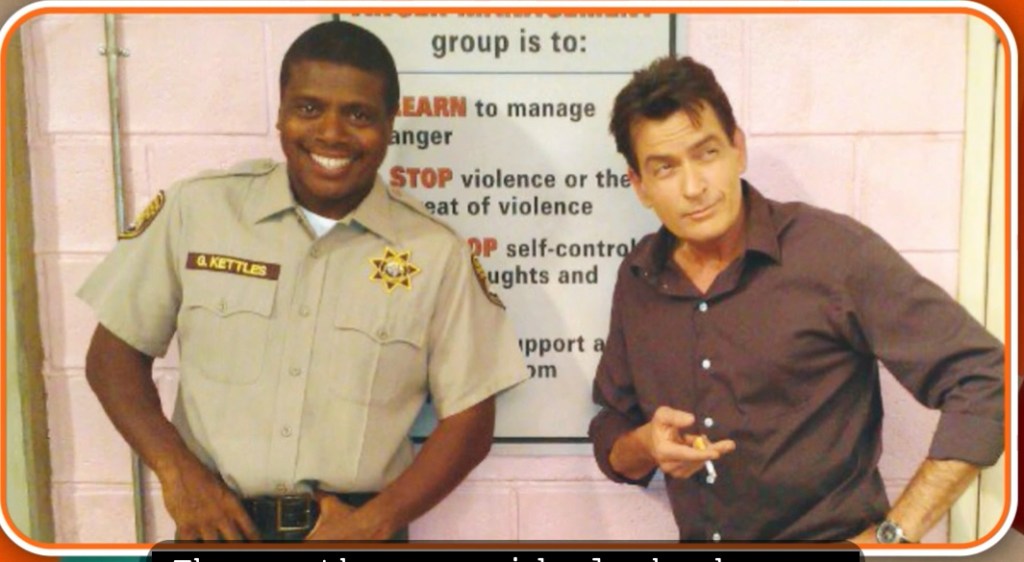

They grew up experiencing the game’s teachable moments of teamwork, following rules and accountability. As Todd says in the “aka Charlie Sheen” documentary, “everyone needs a Black friend.”

And one who also understands the acting business (see: Antonio Todd, someone who once made it on the MLB Network to show off his Rawlings Gold Glove for his role as Minnesota Twins rookie second baseman Micky Scales in “Little Big League” and still enjoys talking about it.)

Carlos Estévez was born in New York on Sept. 3, 1965, the son of acclaimed actor Martin Sheen, younger brother by 3 ½ years of “Brat Pack” actor Emilio Estévez. His father, born Ramon Antonio Gerard Estévez, was performing on Broadway, breaking into show business, starting a family.

Charlie talks in the documentary about being 11 years old when he brought his baseball glove with him to the Philippines to be with his dad on the set of “Apocalypse Now.” When Martin Sheen experienced serious health issues during the shooting, Charlie said tossing the ball around with him seemed therapeutic. For both of them.

“It redefined that age-old moment of a father-son playing catch,” the son says.

(Fast forward to another surreal level of the father-son sports connection — in 1986, a made-for-TV show called “War of the Stars” features the Sheens teaming up to play 2-on-1 against Michael Jordan. They actually win. The show, taped at the Notre Dame High of Sherman Oaks gym, actually exists on video).

Charlie developed an affinity for the Cincinnati Reds during “Big Red Machine” era of the ‘70s, admiring second baseman Joe Morgan. Charlie said part of the connection came as a result of his father coming from Dayton, Ohio.

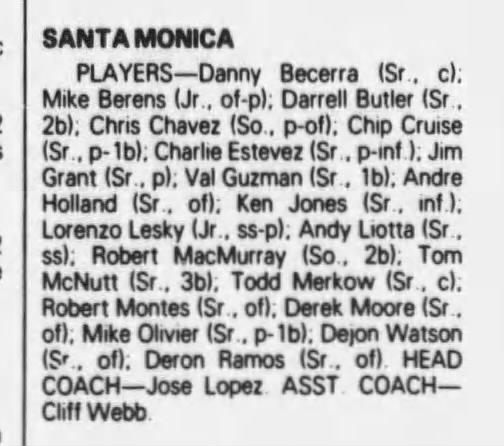

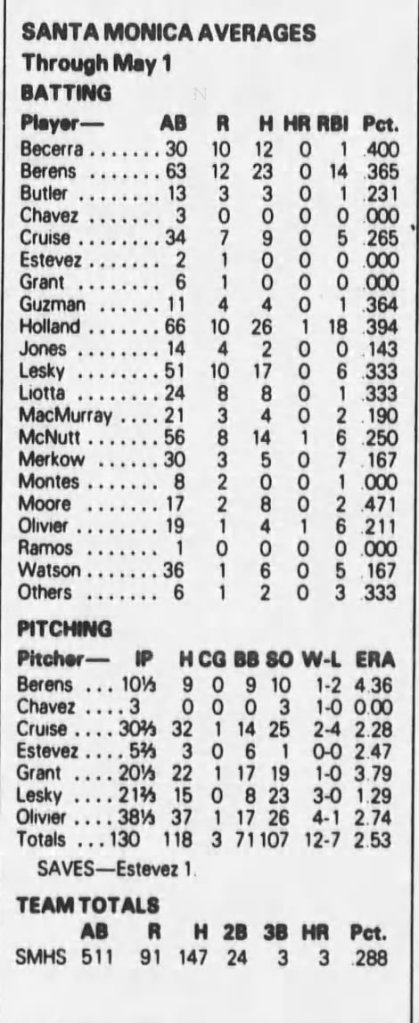

As such, the Estévez/Sheen’s imdb.com bio proclaims he was a “star shortstop and pitcher” with the Santa Monica High Vikings of the early 1980s. Eventually, Estévez focused on pitching because, he admits, he had trouble hitting the curveball.

Jose Lopez, the Santa Monica High baseball coach in 1983, was kind enough to once tell the Los Angeles Times that Estévez was his “bullpen ace” … very, very efficient … an outstanding athlete … with me, a model kid.”

When the Vikings finished third in the Bay League in ’83, they might have used Estévez in the first round of CIF-Southern Section 4A Division playoff game against Hoover High of Glendale. The Vikings fell behind early 3-0 and lost the game, 4-3 in nine innings, eliminated by future major league pitcher Wally Ritchie. Their season ended 14-9.

(Post script: Samohi was eliminated, by the way, in a very painful way. The Vikings’ Mike Berens hit a homer off Ritchie early in the game and leaped to high-five the first-base coach en route to circling the bases. But the umpires ruled he failed to touch first base. Samohi lost the game on a bases-loaded walk surrendered in the bottom of the 10th.)

(Second post script: This is the same Jose Lopez who a decade earlier played three years of baseball and four years of soccer at UCLA, is inducted into the Bruins’ Athletic Hall of Fame, then played three seasons with the Los Angeles Aztecs. He taught AP Spanish Language and Literature at Santa Monica High School for many years after his playing days and coached baseball.)

(Third post script: Todd would have been on that Samohi baseball team as well his senior year, but he tore up his ankle playing football the previous fall season and was in a hip-to-foot cast that didn’t come off until the baseball season ended. It also derailed any hopes of a college football career).

The reason Estévez wasn’t able to help his team in that playoff game — he had been expelled from school two days earlier because of an exceptionally poor GPA and horrendous classroom attendance. Apparently, he couldn’t save himself even if joined the Santa Monica High version of the “Breakfast Club” in Saturday morning detention.

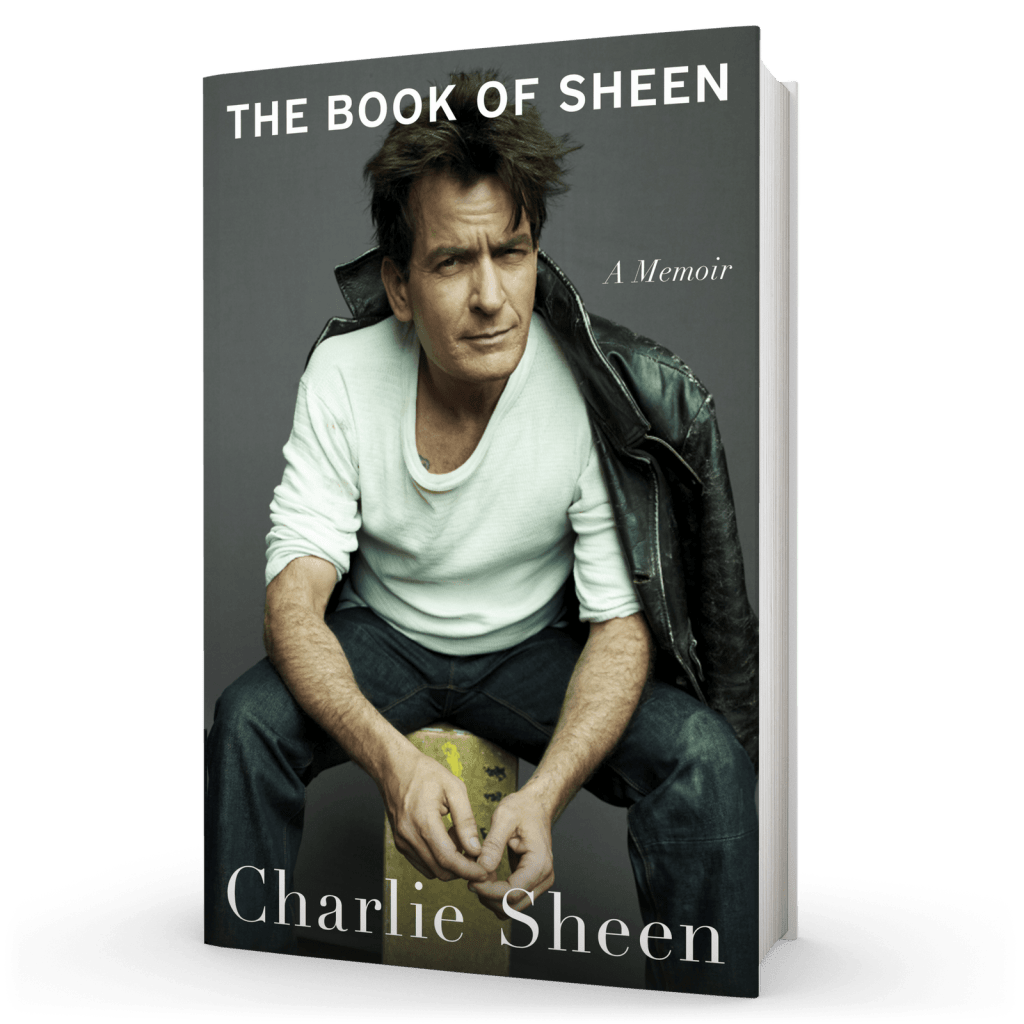

In a 2025 memoir, “The Book of Sheen,” which came out at the time of the “aka” documentary, Charlie Sheen wrote that he only made the sophomore baseball team at Santa Monica High as a hurler because “the key to my success was a pitch I threw that the school hadn’t seen in 10 years — the knuckleball.

“Thrown properly, it dips, jukes and flutters with zero rotation. With thrown improperly, it’s a meatball that usually gets clobbered. The metaphoric intersections were blatant — to survive the next three years, I’d have to emulate this unique weapon in my baseball arsenal. Not a lot of practice with the flutter. Juke and dip? I’m your guy.”

Todd Merkow was the Samohi team catcher first assigned to try to corral Estévez’ knuckleballs.

“Since I caught him a lot from high school to summer leagues at Pepperdine University we played in, I’m not sure anyone else experienced his knuckleball as much as I did,” said Merkow, once the vice president and general manager of Fox Sports West regional cable channel, the president and COO of the Los Angeles Avengers, a sports journalism lecturer at Arizona State and founder of Valiant Sports Society, a non-profit that works to focus on the mental and physical health of youth sports athletes.

“He just loved playing baseball, no matter what position. Baseball was a major part of his life, and it was the bond we had with out friends at the time. Charlie was such a good guy, always fun to do things with.

“It still makes me laugh the first time I caught him in that sophomore scrimmage and his dad was standing behind the backstop as I kept chasing multiple passed balls. I think it got to a point where he and I were joking about it.”

Merkow said he could vouch for Estévez’ Reds fandom, as they went to games together at Dodger Stadium, especially when the Reds played the Dodgers, using season tickets the Estévez’ family had on the loge level down the first base line.

“What also made me laugh was there were a couple of guys that were Mets fans that would sit near him, and they never wanted to know the Mets’ score on the out-of-town scoreboard because they were recording the game. Charlie just loved messing with them.”

For three straight summers, Estévez went to the Mickey Owen Baseball School in Missouri. He writes in the book that he was offered a scholarship at a community college in Kansas called Pratt, which was a feeder to the University of Kansas baseball program.

“I saw an ad in The Sporting News or Baseball Digest when I was in high school,” he told Sports Illustrated. “I went to get scouted. But I looked at the talent there and knew I couldn’t do it for a living. I think my baseball career would have been spent riding buses, not jets, if you know what I mean. So I figured, Hey, I’ll pursue a real idiot’s job instead. Acting!”

Seriously, how close was he to getting scouted and playing college ball?

“There was a coach there who had a cup of coffee with Baltimore, and he made some calls and some guys came out,” Sheen continued. “I got a half ride to a junior college, and if my grades improved I might have gone on to the University of Kansas. That would have been cool. In high school the talent is good, but you don’t get a chance to look at the overall spectrum. That’s what a baseball camp did. Suddenly I’m facing this kid who had just signed with the Phillies, and he’s throwing 98 with left-handed zip. He strikes his first two guys out on six pitches. Four of them curveballs that just come out of the parking lot. I got to see guys who were going to do it for a living. And knew I couldn’t do it for a living.”

At some point, Estévez realized he wasn’t in Kansas anymore. Maybe after he was lured into a credit-card fraud scheme when he was in high school, which he attributes to “curiosity … boredom …sudden profit.” He also said being part of his Class of ’83 ceremony from Santa Monica High was problematic when “I threatened the life of my English teacher. It was the last day of classes my senior year. I needed a C to graduate. She wouldn’t let me take the final because I didn’t have the re-admit, the slip re-admitting me to the classroom. I crumpled up the exam paper and threw it in her face and left.”

(Estévez would get his diploma in 2013 as part of Santa Monica High’s 100th anniversary, bestowed upon him during a bit on “The Tonight Show with Jay Leno” thanks to Todd’s intervention as the Santa Monica High assistant baseball coach.)

It came to a point where Estévez bargained with his parents — let me try this family acting thing, and if it doesn’t work out, I’ll find something else productive.

His first move was changing his name to Charlie Sheen, a surname his father created for his own acting career as a way to honor of the former Catholic Bishop Fulton Sheen. Older brother Emilio had been more adamant about staying with the Estévez birth name. He liked the alliteration.

Charlie Sheen’s first credited acting gig came during the 1983 production of a film called “Grizzly II-Revenge,” abandoned because of poor financing, rediscovered, and released in 2020. Sheen’s commitment to that production overseas eventually led him to turn down what would become a more famous role — Daniel LaRusso, played by Ralph Macchio in the 1984 film, “The Karate Kid.”

By the time Sheen got to show off his baseball skills in the films “Eight Men Out” and “Major League,” which came in 1988 and ’89, he had established himself in “Platoon,” “Wall Street,” and “Young Guns.”

In “Eight Men Out,” Sheen happily played Happy Felsch, the center fielder and reluctant participant in on the scheme by the Chicago Black Sox of 1919 to throw the World Series to appease gamblers and line their pockets against a stingy owner.

Sheen, who says he got the role because brother Emilio was asked first but wasn’t available, pulls on the old-timey uniforms and clumsy leather gloves to play baseball with actors John Cusack (Buck Weaver) and D.B. Sweeney (Shoeless Joe Jackson).

The Los Angeles Times’ Bill Steigerwald described Sheen at the time as a “a mature-looking 22 … more natural in a baseball uniform than in the jungle fatigues … a cool-guy type who patiently endured the assaults of autograph-seeking extras who surrounded him at lunch the day before.”

Sheen had told the writer the he “may need an operation to repair his left shoulder, which he says he injured ‘chasing a curve ball’ while taking ‘BP’ (batting practice) with the Dodgers this summer as part of his preparation for the movie.”

During shooting in Indianapolis, Sheen also told Steigerwald: “This isn’t really a career move. I have, like, three scenes and I’m just one of the guys. But it’s a chance to play in the World Series. It’s something I always wanted to do.”

Sweeney added to the story that “Charlie and I are both here — I risk going out on a limb and speaking for Charlie — first, because it’s a wonderful script about baseball. I think Charlie had some of the same experiences about baseball as I had, about wanting to be a ballplayer, and acting being sort of a second choice.”

Felsch, banned after the 1920 season in which he posted his best offensive numbers with a .338 average, 14 homers and 115 RBIs, admitted he received some $5,000 for his participation in throwing games — almost double his regular-season salary. After hitting .275 during the 1919 season and playing a stellar center field, Felsch hit just .192 (5 for 26) in that World Series.

As Felsch later said to the Chicago American: “Well, the beans are spilled and I think I’m through with baseball — the only profession I know anything about, and a lot of gamblers have gotten rich. The joke seems to be on us.”

Felsch had several baseball cards made of him during his six-year MLB career — and now, so did Sheen, when Pacific Trading Cards issued an “Eight Men Out” set in 1988.

That 1919 White Sox roster of Flesch, Jackson, Weaver, Eddie Collins and Eddie Cicotte played 10 years before numbers started appearing on team jerseys. The practice wasn’t officially adopted until 1937.

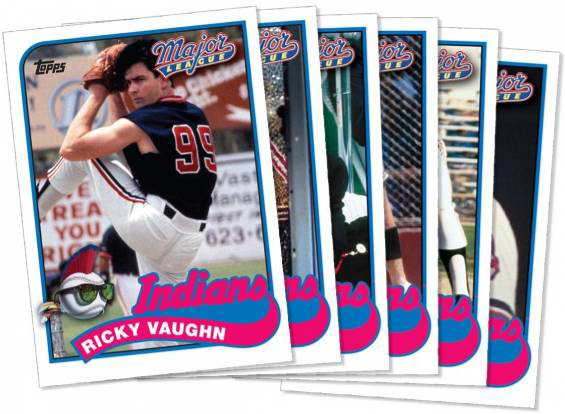

But on the 1988 Cleveland Indians fictional roster featured in the movie “Major League,” No. 99 wasn’t an afterthought. It was front and center, starting the theater posters.

A script centered on how a team intentionally made up of spare parts and misfits rallied against the new Indians owner that wanted to lose as an excuse to shift the franchise to Miami. Sheen was given the amp up his bad-boy persona from his memorable scene from the police station in “Ferris Bueller’s Day Off” and kick it up a few notches to make Indians relief pitcher Ricky Vaughn a character so noteworthy, the movie’s marketing logo became a baseball adorned in sun glasses and a fringe-painted Mohawk haircut.

In the R-rated film, Vaughn makes his appearance at spring training in Arizona, just released from jail, with cutoff sleeves pitching off the mound. A teammate pranks him, making him think he was cut from the roster, which sets Vaughn off, sparking a fight. Vaughn then marches into the manager’s office:

“I got news for you Mr. Brown,” Sheen growls as Vaughn. “You haven’t heard the last of me. You may think I’m shit now, but someday you’re gonna be sorry you cut me. I’m gonna catch on somewhere else and every time that I pitch against you I’m gonna stick it up you’re fuckin’ ass!”

Vaughn then throws a ball against a locker.

“Good, I like that kind of spirit in a player,” replies the crusty manager Lou Brown (played by James Gammon). “The only problem is I didn’t cut you. …I think someone’s been having some fun with you.”

Eventually, Indians outfielder Willie Mays Hayes (Wesley Snipes) approaches Vaughn and asks: “What the hell league you been playing in?”

Vaughn: “California Penal.”

Hayes: “Never heard of it. How’d you end up playing there?”

Vaughn: “Stole a car.”

From then on, Sheen, as Vaughn, was a scene stealer. It helped that Bob Uecker unloaded his famous line, “JUST a bit outside,” from the broadcast booth when describing one of Vaughn’s wild pitches.

Maybe this gritty, unpolished and unpredictable Vaughn was believable because of Sheen’s real life experiences. Also a foreshadow to Sheen typecasting.

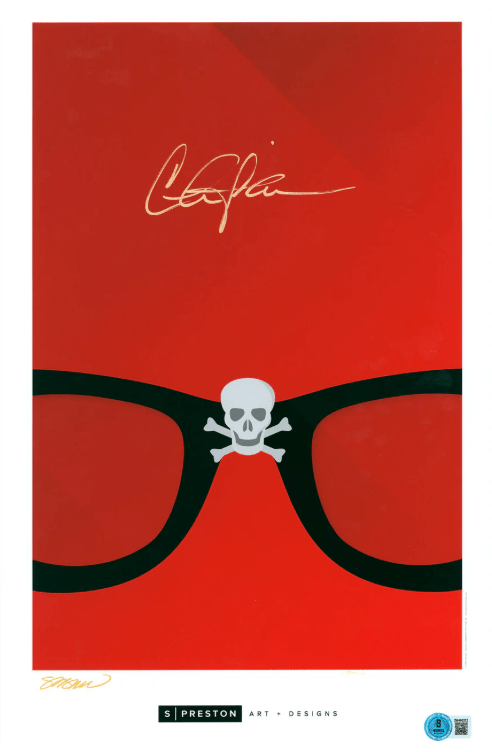

The Vaughn “concept” wasn’t complete without fans screaming the lines to The Troggs’ hit from the 1960s, “Wild Thing … I think I love you!” as it blared over the stadium speakers. Vaughn then made black-rim glasses with a skull and crossbones insignia looks cool after an eye exam.

At this point, Sheen wasn’t messing with the knucklehead any more.

In 2019, at a time when put up for auction the Indians cap he wore in the film as well as a ball used in a scene where he was recorded as throwing a 101 mph pitch, Sheen said he threw a solid “84 to 85 mph” on the movie set, and “I remember my arm being completely wrung out from all of the pitching that I did throughout the movie and that final game sequence that we shot. … That was the last time I was ever able to throw a baseball with that kind of velocity from the mound.”

Still, a PG-rated version of a sequel squeezed out in 1994, Vaughn returned and proclaimed he had a new pitch called “The Eliminator.” While “Major League II” brought back much of the original cast, the Vaughn subplot was about how he had “become a media sensation and is more concerned about his public image than his pitching.”

In one scene, Vaughn quarrels with Hayes and the two begin fighting, leading to the entire team in a brawl with each other getting ejected during a game against the Boston Red Sox.

Spoiler alert: Vaughn is called in to get the last out of Game 7 of the ALCS. He walks the first hitter so he can get to former teammate Jack Parkman (David Keith) before striking him out to clinch the title.

For the 1998 third try of “Major League: Back to the Minors,” Sheen, and most of the others, weren’t interested. That’s a minor quibble.

It didn’t matter much to Sheen, who, by age 30 in 1995, had his star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame.

Sheen’s Hollywood trajectory in the 1990s after “Major League” was somewhat of a major-league hit-and-miss — interventions, drug overdoses, drug rehab, gambling issues, womanizing, a Heidi Fless trial appearance, claims of spousal abuse, admitting to being HIV-positive to avoid blackmail, a bizarre one-man show focused on “Winning!” — his comebacks included winning a Golden Globe for best actor in a TV comedy for “Spin City” in 2001 and then for “Two and a Half Men” in 2006. “Anger Management,” his last TV series role, came in 2012.

The fact Sheen has appeared in three films selected for the National Film Registry by the Library of Congress as being “culturally, historically or aesthetically” significant — Badlands (1973), Ferris Bueller’s Day Off (1986) and Platoon (1986) — speaks to his choices. It was said Sheen was also up for the role of Nuke LaLoosh in “Bull Durham” before it was given to Tim Robbins.

Maybe because the concept of Ricky Vaughn never spun too far away from the Sheen aura.

Michael Weinreb, a sports and pop culture writer, called “Major League” a “broad fairy tale, but it works because it’s also grounded in reality.”

Weinreb notes how screenwriter David S. Ward “based the character of Ricky Vaughn on hard-throwing pitchers like the Yankees’ Ryne Duren,” a right-hander who also spent two seasons with the expansion Los Angeles Angels (8-21, 4.86 ERA, 182 strikeouts and 132 walks in 170 innings).

A bio created for Ricky Vaughn by Baseball-Reference.com notes that the most linkable MLB player to Vaughn came in the form of real-life relief pitcher Mitch Williams.

Williams, a Santa Anita-born left-hander, seized the nickname “Wild Thing” because of an awkward delivery that caused him to fall to the third base side of the mound during his follow through. And, yes, he had control issues.

Williams wore No. 28 for Texas (1986 to 88), the Chicago Cubs (’89 and ’90) and the first two years he was in Philadelphia (’91 and ’92) before taking on No. 99 for the Phillies in 1993, four years after “Major League” became a cult hit. Back in Chicago, the Wrigley Field organist played “Wild Thing” when Williams entered the game from the bullpen in 1989, the year of the film’s release. Then-Cubs manager Don Zimmer once said that Williams, who made his only All-Star Game appearance at Anaheim Stadium in 1989 by pitching the final inning, “did everything 99 miles an hour.” Eventually, Williams came into games with The Trogs’ soundtrack.

Williams insisted his number switch to No. 99 wasn’t because of Vaughn, but his admiration for Mark Gastineau, who wore No. 99 for the NFL’s New York Jets.

Williams kept No. 99 in Houston in ’94 and then for the Angels in ’95 when his career ended.

More than 30 MLB players have worn the otherwise attention-seeking No. 99 over the years — perhaps most visible now as New York Yankees MVP outfielder Aaron Judge. Yankees outfielder Charlie Keller was actually the first to wear No. 99 in 1952. Boston Red Sox outfielder Alex Verdugo, who came up as No. 61 and then had No. 27 with the Los Angeles Dodgers, took it as a badge of honor to wear No. 99 when he was traded away in a deal for Mookie Betts.

Other MLB pitchers who likely sported No. 99 as an homage to Vaughn in one way or another:

== Joe Kelly: No. 58 seemed to suit the right-handed reliever born in Anaheim who played at Corona High and UC Riverside when he came with the St. Louis Cardinals. In his college bio, he created a story that he was as a distant relative of the Prohibition-era gangster George “Machine Gun” Kelly. It wasn’t true, but it followed him into the big leagues and explained a lot of who Joe Kelly was. After winning a World Series with Boston in 2018, he came to the Dodgers and wore No. 17 until 2021, took it to the Chicago White Sox, and brought it back to L.A. in 2023. But in 2024, change was happening. Shohei Ohtani, who wore No. 17 for the Los Angeles Angels in his first six seasons in Anaheim, was a free agent and considering the Dodgers as a preferred choice. Joe Kelly’s wife, Ashley, launched a viral campaign called #Ohtake17, part of the lure to get Ohtani with the Dodgers. Whether or not that was the deal breaker, Ohtani gifted Ashley with a silver Porsche as a thank-you gesture for Joe giving up No. 17. “I wasn’t going to give it up to just anybody,” Kelly said after Ohtani was announced as his new teammate. “If Shohei keeps performing, he’ll be a future Hall of Famer and I’ll be able to have my number retired. That’s the closest I’ll get to the Hall of Fame.” Kelly posted a 1-1 record and 4.78 ERA in 35 games in 2024 before retiring, but not before the Dodgers had a Kelly No. 99 uniform giveaway.

Since then, number 99 is now worn by Dodgers pitching coach Mark Prior (often underneath his sweatjacket, which he removed for the 2025 MLB All Star Game in Atlanta to expose it.

== Keynan Middleton: The right-handed reliever debuted with No. 39 as a Los Angeles Angel in 2017, but he said he switched to No. 99 after coming back from Tommy John Surgery, a new man for the ’19 and ’20 seasons. He kept it when he went to Seattle (’21). Arizona (’22) and the Chicago White Sox (’23), because of his affection for Ricky Vaughn. “I’ve got a little bit of ‘Wild Thing’ in me,” he joked. Middleton had to give it up when he was traded to the Yankees at the end of the ’23 season.

== Spencer Strider: The right-handed starter switched to No. 99 in 2023 after two seasons in Atlanta wearing No. 65. Strider admitted his favorite movie is “Major League,” he relates to Rick Vaughn, and he also uses No. 99 when he adds himself to the roster while playing MLB The Show. The change produced a 20-5 season, an NL All-Star selection, and he led the league with 281 strikeouts. He had Tommy John surgery the next year and continues on a comeback journey.

== Turk Wendell: Started wearing it in 1997 with the New York Mets through 2001, then in Philadelphia — before giving it up to Mitch Williams for a season. Wendell got it back in Colorado in ’04. When the superstitious Wendell joined the Mets, his usual No. 13 was not available, so he asked for No. 99, without reference to ‘Major League’ – he simply thought it was cool. The 33-year-old Wendell signed a three-year contract with the Mets that will pay him $9,999,999.99 for appearing in 70 games in each of the next three seasons.

== Taijuan Walker: Started with No. 99 in 2017 with Arizona, then ’20 with Seattle, ’21 with the New York Mets and ’23 with Philadelphia. When Arizona equipment manager Roger Riley asked Walker his number preference, he went with No. 99. “It was the first number that popped into my head,” Walker said. “No one really wears 99, so I shouldn’t have a problem keeping it.”

Two actual Cleveland Indians/Guardians players wore No. 99:

== Dan Robertston (2017). The outfielder took No. 99 for his final MLB season. The Sunny Hills High standout born in Fontana also wore No. 44 for the Angels in 2015, which has not been retired for Reggie Jackson). Robertson was asked in a Q&A with the New York Times about his number choice:

Q: Why did you pick No. 99 as your uniform number? “I played at Concordia University before I transferred to Oregon State. We had to wear ugly, like, mustard yellow pullovers at our school. We all had the same jerseys. They said ‘Eagles’ on the front and ‘99’ on the back. All of us had the same jersey. The message behind it was, all that energy that happens in the ninth inning in the stadium, in the dugouts, whatever, channel that for nine innings and play that with that kind of energy from the first pitch. I just kind of adopted that. I got the first opportunity to wear it last year with Seattle. Now, I’m just not going to change it.”

Q: Did you know you’re the only player in team history to wear No. 99 — outside of Ricky Vaughn? “Me and my wife, we watched ‘Major League’ this offseason to freshen up on Cleveland history, even though it’s fictional, that’s still part of it. When I saw him wearing No. 99, we talked about, ‘Hey, do I get the haircut?’ And she just looked at me like, ‘No. You just go out there and play.’”

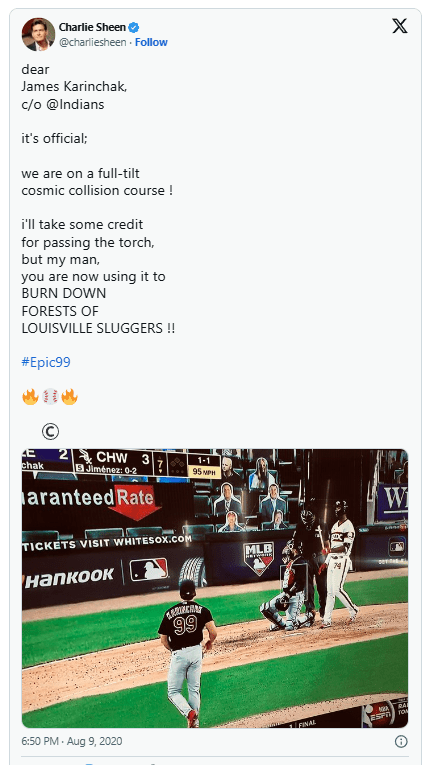

== James Karinchak (2020 to ’23), a right-handed middle-innings reliever who started his career in Cleveland wearing No. 70, switched to No. 99 and also came into the games at Progressive Field with the same “Wild Thing” version playing as he warmed up. Sheen notice, of course.

== Billy Ray “Rojo” Johnson (2010). Can we count this? As another blur between reality and Hollywood, Will Ferrell once took on the name, and persona, of an angry relief pitcher for the Triple-A Round Rock Express against the Nashville Sounds. He threw one pitch and got into a “brawl.” Ferrell created the backstory: Johnson, a fire-balling right-handed phenom, was born in the U.S. but raised in Venezuela. He had been serving time in a central Texas prison for running a smuggling ring that imported rare and illegal species of reptiles into the U.S. Upon his release he joined the Express and, on Thursday, May 6, wearing gold chains and toting a bag full of beers, he threw his first pitch went behind the Sounds player and was immediately ejected. He eventually left the field, but not before fighting with the umpire and spraying the Sounds player with beer. Johnson was asked to make a return during the 2011 season but declined citing the affiliation change. “Rojo doesn’t play for an American League team,” Johnson said. “I don’t just pitch, I also hit. When the Express changed their affiliation from the Astros to the Rangers, I decided to hang up the cleats. I’m a National League guy.”

The perfect candidate who never (so far) has worn No. 99: Carlos Estévez.

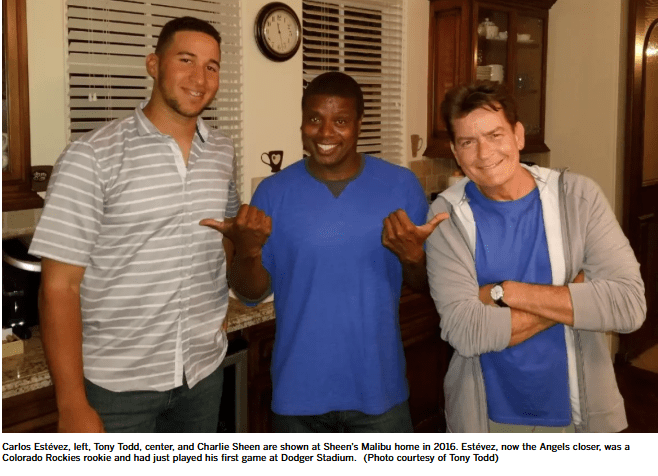

The Los Angeles Angels picked up the relief pitcher by that name in 2023, watching him become a member of the AL All-Star team as he saved 31 games in 63 appearances. Charlie Sheen already knew about him, and wanted to make a connection. Todd, through his friend, Colorado Rockies first-base coach and former Dodgers infielder Eric Young, invited Estévez to Sheen’s Malibu home for lunch in 2016 after his first game at Dodger Stadium, pitching for Colorado.

“It was really cool,” said Estévez, who had 51 saves in two seasons with the Angels. “We got to talk about how weird it was that we had the same name, and how cool it was at the same time, because of the ‘Major League’ movie.”

Estévez, who also made the AL All Star team with Kansas City in 2025 and had a league-best 42 saves, also told the Los Angeles Times: “I had no idea how big a fan of baseball he is. It’s insane, he knows so much about baseball. He told me, ‘I’ve been following you since you were pitching in Modesto.’ ”

The afterlife of Ricky Vaughn has been preserved well. More than just Funko Pop dolls, bobbleheads and more jersey sales.

One website, MinorLeagueBall.com, even created a fictional backstory on him — aligned with Charlie Sheen’s real life timeline:

*Drafted by the Los Angeles Dodgers in the fifth round of the 1984 draft, out of high school in Malibu

* Spent 1984 at in Rookie Ball, spent ’85, ’86 and ’87 at Single-A Great Falls, Vero Beach and Bakersfield

*Released by Dodgers May 1, 1987 following arrest for grand theft auto

*Pitched in California Penal League 1988 (no statistics kept)

*Signed by Indians as a free agent, February 9, 1989

*Spent the whole ’93 season on the injured list.

* Had a career line of seven seasons: A 46-40 record and 3.78 ERA in 189 games (103 starts), 732 innings, 613 strike outs, 325 balks, 680 hits, five saves. Not sure how many wild pitches.

Pop Fly Art Prints sells a comic-book cover creation available in the National Baseball Hall of Fame online store, a product touted as a way to celebrate “baseball’s cultural legacy.” The item is often sold out.

TikTok videos show how to get a haircut that matches the Ricky Vaughn look with jagged edges behind the ears.

There’s the tale of a star of the Pro Bull Riding circuit named Ricky Vaughn, a bull said to “as sweet as a golden retriever” that had once been blind in one eye until it regained its sight and became a champion.

“He’s got the best personality, and anybody that’s interested in being in the bull business, or is a fan of bucking bulls, needs to meet him because he’s that kind of deal,” said his owner, HD Page.

Through all his games of pickle with Hollywood success and getting tagged out in a rundown, Sheen’s connection to baseball remains golden.

In 1992, he paid a reported $93,500 at auction to take ownership of the ball Mookie Wilson hit under the glove of Bill Buckner in Game 6 of the 1986 World Series.

In 1996, he paid more than $5,000 to buy all 2,600-plus seats behind the left-field fence at Anaheim Stadium for an Angels-Tigers Friday night game, in the desire to increase his chances of catching a home-run ball for the first time. He sat with three friends about 20 rows back, pounding his glove. The one homer hit in the game by the Angels’ Tim Wallach went to right field.

As “Major League” became a frequent re-run on the MLB Network and other cable channels, DirecTV did some commercial spots in 2007 that featured Sheen as Vaughn. Sheen got to take some BP between takes at Dodger Stadium. This happened.

It was almost like Sheen and Todd could pass off as a version of “White Men Can’t Jump,” creating a sandbag situation to win a bet or two on Sheen’s baseball abilities before stunned observers.

In 2016, when the real Cleveland Indians made it to the World Series against the Chicago Cubs, there was a social media movement to have Sheen throw out the first pitch in the opener.

Sheen was ready to do the honors for the Indians, but he didn’t get the call.

It didn’t hurt that, in 2014, Topps issued its own Ricky Vaughn baseball card as part of its “archives” collection for the film, celebrating its 25th anniversary.

In 2017, Sheen continued his decluttering by putting up for auction his ownership of a Babe Ruth 1927 World Series ring and Ruth’s 1919 transfer contract from the Red Sox to the Yankees.

Baseball never left Sheen’s line of vision. He was part of its history even if he never played one game as a professional. Maybe there’s a time and place for a baseball film where Sheen plays a former MLB reliever-turned-bullpen coach who teaches life lessons to an entitled newbie who can’t handle his stardom.

The photos and Super 8 millimeter film may look grainy now, but in his tell-most book, Sheen shares a variety of photos showing him playing baseball. He wears No. 5 in a Malibu Little League Astros uniform with his self-described “gully-joint” hat “worn properly” in 1977. He is shown pitching and hitting in a PONY league game from 1978.

From 1998, there’s a shot of him hitting, “a self-taught lefty,” during his time at the Promises rehab in Malibu. The reason he hit lefty, he admitted in an SI story, was because he was a fan of Reggie Jackson. A shot of him with Reggie Jackson from the set of the 1997 movie “Bad Day on the Block”/ “Under Pressure” is also in the book. Sheen had created an indoor batting cage for himself at his home in Malibu and spent hours refining the left-handed swing.

Another poignant photo is of Charlie and Martin Sheen at the Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown in 1990.

In the “aka, Charlie Sheen,” doc, one story told is about how Sheen and former wife Denise Richards had their first date in 1998 at Sheen’s Westwood apartment eating take-out. They stayed in because Sheen didn’t want to miss a chance to see Barry Bonds on TV hit his 70th homer of the season as the San Francisco Giants were playing in Houston.

Tony Todd’s video collection of times with Sheen includes a hitting display at Oak Park and Santa Clarita Hart high schools around 2008. That’s where Sheen hit a home run Todd estimated traveled 445 feet at Oak Park and hit a barrage of homers at Hart in the presence of Hall of Fame slugger Eddie Murray and the Hart High team.

Todd becomes emotional in the documentary when he explains how, in ’98, Charlie’s father Martin had picked him up from rehab, and within 20 minutes, granted Charlie’s wish to find a baseball field. They went over to Malibu High’s campus. A men’s pickup game was going on and Todd talked them into letting Charlie play.

He gets in and goes into the left-handed hitters box.

“This is one of the best moments … my man gets up during the game and he hits a home run in front of his dad,” says Todd. “Just leaving rehab … I could not believe that actually happened. I wish I had the ball.”

Actually, for what it’s worth, Sheen did get the ball:

The Hollywood sports numbers

Is Ricky Vaughn the most well-known No. 99 in Hollywood sports flick history?

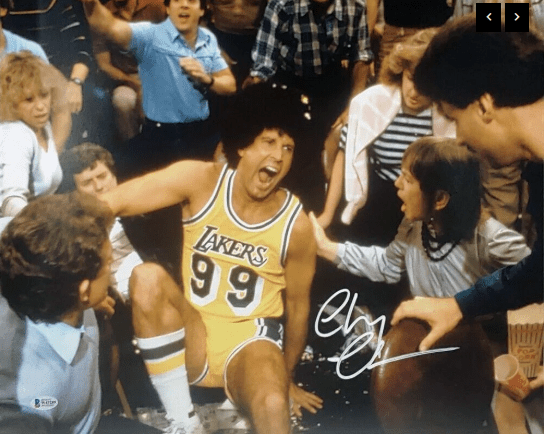

Chevy Chase has a cult following when he went undercover in a Lakers’ No. 99 jersey and Afro wig as Irwin “Fletch” Fletcher from the movies “Fletch” (1985) and “Fletch Lives” (1989).

Fans of the “Mighty Ducks” franchise might remember Adam Banks (Vincent Larusso) going from No. 9 on the rival Hawks team to No. 99 when he joined the Ducks — for three movies.

Sports characters on film go back to 1898 when “The Ball Game” was considered a “documentary” that showed a game between Reading and Newark as an experiment to see how film might record history.

“Right Off The Bat” was the first baseball drama in 1915 staring MLB player Mike Donlin in somewhat of a biopick. (More on Donlin from this review of a biography done on him in 2024).

Harold Lloyd was already doing crazy things with nutty props by the time he appeared as Harold “Speedy” Lamb, a college football player in “The Freshman” (1925).

Lloyd starts out wearing No. 0 as he waits to get into the football game, but he is forced to give up his jersey to a “healthy” player as injuries start mounting. Eventually he gets into the game wearing a white numberless shirt (he is easier to spot for the movie viewers) and the highlight is when he goes the length of the field to score the game-winning TD after a) blocking a field goal, b) making a game-saving tackle and c) recovering a fumble, all on the same play, as time expires. (Game sequences were filmed at the Rose Bowl, and football scenes were filmed at USC).

A good many players and teams are fictional, products of the Southern California creative think tanks of script writers and show runners. But in the process, the use numbers on jerseys to try to make them as authentic as possible.

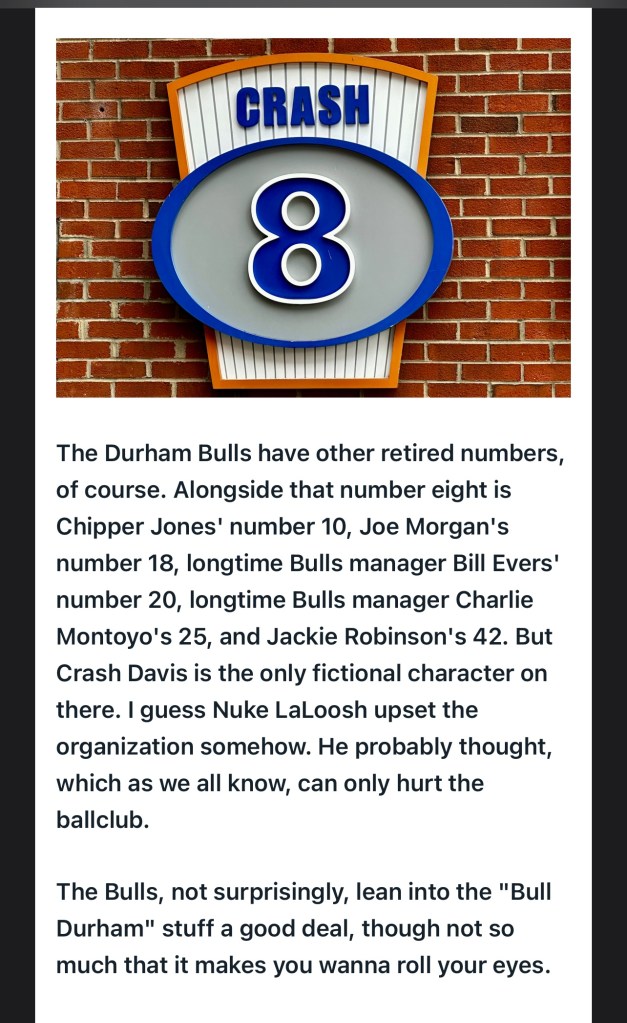

Kevin Costner might be best known as No. 8 playing Crash Davis in “Bull Durham,” but he came back 10 years later to wear No. 14 as Billy Chappel in “For Love of the Game.”

Joe Pendleton wore No. 16 for the Los Angeles Rams when he (played by Warren Beatty) took them to the Super Bowl at the Coliseum against Pittsburgh in the 1978 movie “Heaven Can Wait.” It matched up with NFL Film archived footage. And it happened just a year before the real Rams and real Steelers played in the Super Bowl, at the Rose Bowl.

When the Marx Brothers made “Horse Feathers” in 1932, Groucho wore No. 13 (as Professor Quincy Adams Wagstaff), Chico had No. 11 (as Baravelli), Harpo had No. 0 (as Pinky) and Zeppo had No. 8 (as Frank Wagstaff). A bit different from what the movie poster showed.

Eventually, the Three Stooges had their own take on a numbering system on the football field when filming movies at the old Gilmore Stadium in the 1934 short “Three Little Pigskins” (mistaken by bad men to be the “Three Horsemen of Boulder Dam”) in a movie with Lucille Ball:

Years later, in the 1996 movie “Space Jam,” consider it an homage to the Stooges when the Tune’s Squad included 1/2 (Tweety Bird), a heart symbol (Pepe Le Pew), an exclamation point (The Tasmanian Devil) and a question mark (Beaky Buzzard).

A 2012 Bleacher Report 64-person bracket of the “best fictional athletes” determined Roy Hobbs (Robert Redford) as the winner. In a 2019 ESPN post written by Peter Keating trying to determine the “best fictional athlete in movie history,” starting a 32-person bracket and quizzing ESPN staffers, Sylvester Stallone’s portrayal of “Rocky” came out on top — but, as a boxer, of course he didn’t wear a number. Runner up: Dottie Hinson (Geena Davis), who wore No. 8 in “A League of Their Own” (1992).

In 2013, something called the “Fictitious Athlete Hall of Fame” came about, even garnishing a Wikipedia entry. Ricky “Wild Thing” Vaughn was inducted in 2014.

In the grand roster of Hollywood sports figures on TV screen and silver screen, who do we see that can be added, subtracted or multiplied?

No. 00:

= Willie Mays Hayes (Wesley Snipes) in “Major League” (1989)

= Barney Gorman (Tony Danza) in “The Garbage Picking Field Goal Kicking Philadelphia Phenomenom” (1998)

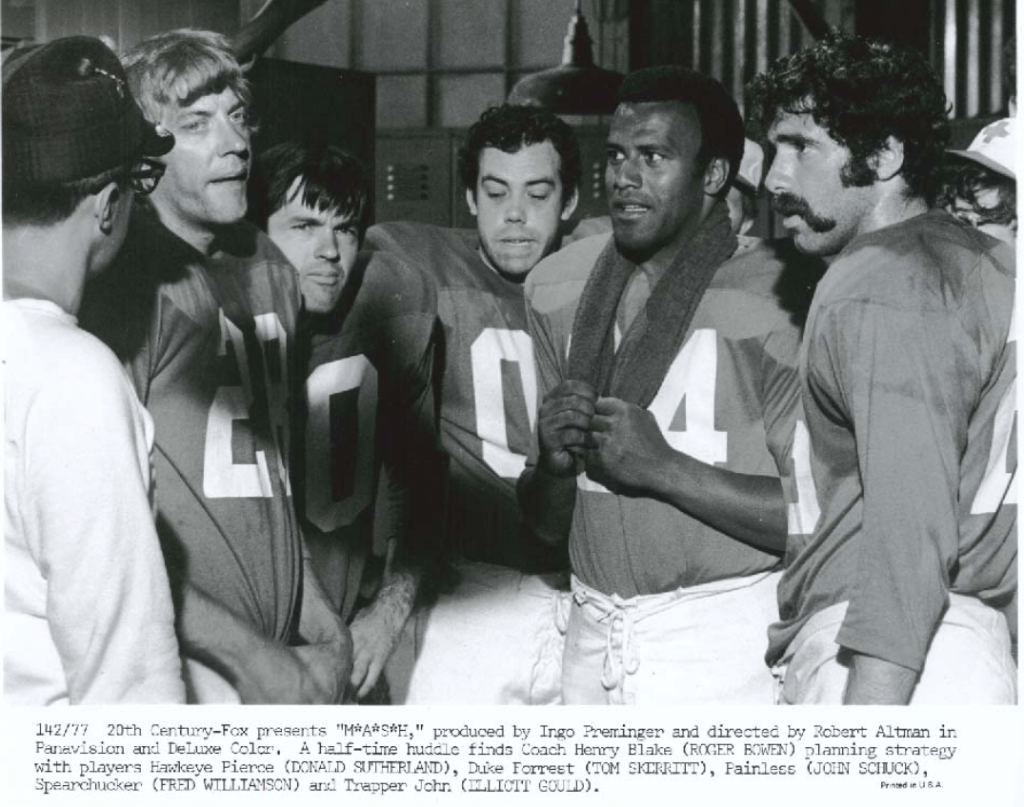

= Captain Walter “Painless Pole” Waldowski (John Schuck) in “M*A*S*H” (1970)

Note: The historic background to Waldowski/Schuck: According to director Robert Altman, this was the first R-rated movie to use a notorious four-letter word. During second unit shooting for the football game chaotic, high-stakes match staged near the end of the movie between the 4077th MASH and the 325th Evacuation Hospital, which consumes about 15 minutes of the final part of the film and includes “ringer” players that are actual NFL players at the time (such as Fred “The Hammer” Williamson, Ben Davidson, Johnny Unitas and Fran Tarkenton), Schuck was told to say something “really nasty” to his opponent. As Schuck lined up against Davidson, he came up with: “All right, bub, your fuckin’ head is coming right off.” Davidson responded by colliding with Schuck hard enough to knock him out cold. Alman loved the raw authenticity of the moment and decided to keep it in the final cut. It has been said that the word was forbidden by any major studio under the Hays Code. By 1968, the Hays Code was replaced by the MPAA rating system, which allowed more freedom, as long as films received an appropriate rating. M*A*S*H, rated R, became the first major American film to use the word “fuck” in dialogue — which in modern times, seems almost like a throw-away line.

No. 0:

= George Plimpton (Alan Alda) in “Paper Lion” (1968).

Plimpton also wore No. 0 on the cover of his 1966 book, “Paper Lion,” when he tried to play third-string quarterback for the Detroit Lions. When Alda played Plimpton he also wore No. 0 for a team scrimmage and during the end of an exhibition game for the Detroit Lions against the St. Louis Cardinals. He also wore No. 17 in practice. It’s also noted that Alex Karras wore his own No. 71 and Lions teammates kept their own numbers in the film. On the cover of one VHS version of the movie, Alda is somehow wearing No. 88.

No. 1:

= Bingo Long (Billy Dee Williams” in “The Bingo Long Traveling All-Stars & Motor Kings” (1976)

= Lucy Draper (Kathy Ireland) in “Necessary Roughness” (1991)

= Robert Hatch (Sylvester Stallone) in “Victory” (1981)

= Dean Youngblood (Rob Lowe) in “Youngblood” (1986)

= Henry Rowengartner (Thomas Ian Nicholas) in “Rookie of the Year” (1993)

= Joe Kingman (Dwayne “The Rock” Johnson) in “The Game Plan” (2007)

= Jacques “Le Coq” Grande (Justin Timberlake), a Los Angeles Kings goalie, in “The Love Guru” (2008)

No. 2:

= Leon Carter (James Earl Jones) in “Bingo Long’s Traveling All Stars and Motor Kings” (1976)

= Lewis Scott (Damon Wayans) as a Utah Jazz player in “Celtic Pride” (1996)

No. 3:

= Kelly Leak (Jackie Earle Haley) in “The Bad News Bears” (1976)

= John Colby (Michael Caine) in “Victory” (1981)

= Leo Wiggins (Robert Downey Jr.) in “Johnny Be Good” (1988)

= Babe Ruth (William Bendix) in “The Babe Ruth Story” (1948)

= Babe Ruth (John Goodman) in “The Babe” (1992)

= Duke (Willie Mueller), the New York Yankees relief pitcher, in “Major League” (1989) (Read his SABR bio project post)

= George Bailey (James Stewart) in “It’s A Wonderful Life” (1946) in the scene after he falls into the pool and needs a football shirt to wear home.

No. 4:

= Jonathan “Mox” Moxon (James Van Der Beek) in “Varsity Blues” (1999)

= Lou Collins (Timothy Busfield) in “Little Big League” (1994)

= Lou Gehrig (Gary Cooper) in “Pride of the Yankees” (1942)

No. 5:

= Michael Delaney (Steve McQueen) in the car driven in “Le Mans” (1971)

= Jackie Robinson (J.R.) Cooper (Gary Coleman) as a San Diego Padres batboy-turned-manager in “The Kid from Left Field” (1979)

= “All The Way” Mae Mordabito (Madonna) in “A League of Their Own” (1992)

No. 6:

= Clu Haywood (Pete Vukovich) in “Major League” (1989) (Read more on the SABR bio project post)

No. 7:

= Jake Taylor (Tom Berenger) in “Major League” (1989)

= Reggie Dunlop (Paul Newman) in “Slap Shot” (1977)

= Oliver Barrett (Ryan O’Neal) as a Harvard hockey player in “Love Story” (1970)

= Clarence “Coffee” Black (Andre “3000” Benjamin) in “Semi-Pro” (2008)

= Hank (Hank Luisetti) in “Campus Confessions” (1938), Betty Grable’s first starring role.

= Jess Bhamra (Parminder Nagra) in “Bend It Like Beckham” (2002) (wearing Beckham’s number)

= Eddie O’Brien (Gene Kelly) in “Take Me Out to the Ball Game” (1949)

= Mickey Mantle (Thomas Jane) in “61*” (2001)

No. 8:

= Crash Davis (Kevin Costner) in “Bull Durham” (1988) (although in some scenes, you’ll see him wearing a helmet with the No. 20 on the back as he’s wearing it backwards while making trips to the mound)

= Dottie Hinson (Geena Davis) in “A League of Their Own” (1992)

= Dennis Ryan (Frank Sinatra) in “Take Me Out to the Ball Game” (1949)

= Jonathan E (James Caan) in “Rollerball” (1975)

= Ron LeFlore (LeVar Burton) in “One In a Million: The Ron LeFlore Story” (1978)

= Duke Temple (Steve Yeager) in “Major League” (1989) (the ex-Dodgers catcher couldn’t even get his old No. 7 as the Indians coach)

No. 9:

= Roy Hobbs (Robert Redford) in “The Natural” (1984)

= Ray McElrathbey (Jay Reeves) in “Safety” (2020)

= Johnny Walker (Anthony Michael Hall) in “Johnny Be Good” (1988)

= Roger Maris (Barry Pepper) in “61*” (2001)

= Jackie Robinson (Chadwick Boseman) as a member of the Montreal Royals in “42” (2013)

= Bobby Boucher (Adam Sandler) as the South Central Louisiana State University Mud Dogs linebacker in “The Waterboy” (1998)

No. 10:

= Cpl. Luis Fernandez (Pele) in “Victory” (1981)

= Sheriff John Biebe (Russell Crowe) in “Mystery, Alaska” (1999)

= Henry Steele (Robby Benson) in “One on One” (1977)

No. 11:

= Johnny Hanson (John Wayne) as a New York Panthers hockey player in “Idol of the Crowds” (1937) (Watch it at this link). Marion Morrison/John Wayne started his acting career, along with some of his USC football teammates as uncredited players in “Brown of Harvard” (1926), “The Draw-back,” (1927), “The Drop Kick” (1927) and “The Forward Pass” (1928).

= K.C. Carr (Raquel Welch) in “Kansas City Bomber” (1972)

= Francis “Ike” Farrell (Joe. E. Brown) in “Alibi Ike” (1935)

= Ed Monix (Woodie Harrelson) in “Semi-Pro” (2008)

= Arthur Agee in Hoop Dreams (1994) (to honor his idol, Isiah Thomas)

= Amanda Whurlitzer (Tatum O’Neal) in “The Bad News Bears” (1976)

= Mickey Scales (Tony Todd) in “Little Big League” (1994) (with more video evidence of his playing abilities)

No. 12:

= Tanner Boyle (Chris Barnes) in “The Bad News Bears” (1976)

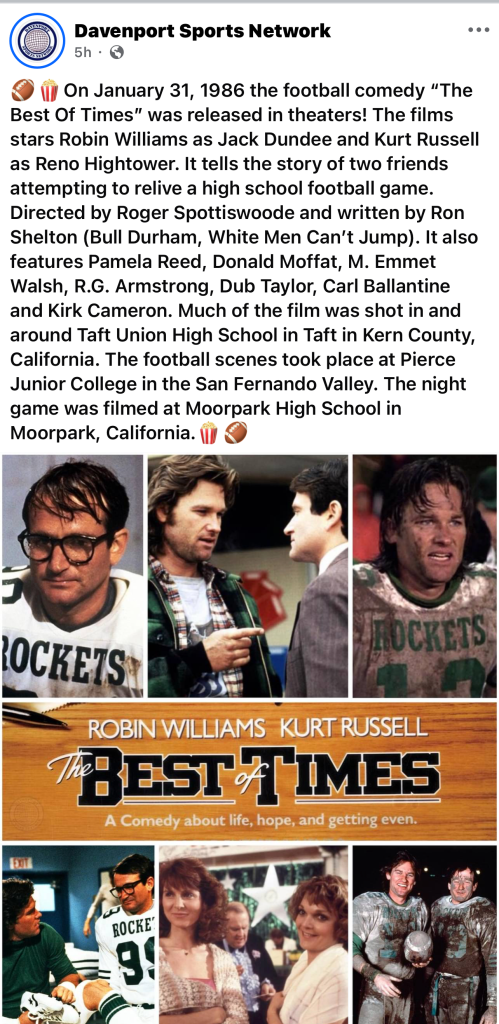

= Reno Hightower (Kurt Russell) in “The Best of Times” (1986)

= Scott Bakula (Paul Blake), the Texas State Armadillos QB in “Necessary Roughness” (1991)

= Jim Gregory (Bruce Jenner) in “Grambling’s White Tiger” (1981)

No. 13:

= Willie Beaman (Jamie Foxx) in “Any Given Sunday” (1999)

= Pedro Cerrano (Dennis Haysbert) in “Major League” (1989)

= Sam Tuttle (Michael Papajohn) in “For Love of the Game” (1999)

= Professor Vernon K. Simpson (Ray Milland) in “It Happens Every Spring” (1949)

No. 14:

= Billy Chapel (Kevin Costner) in “For Love of the Game” (1999)

= Michelle Langford (Vivica A. Fox) in “Juwanna Mann” (2002)

= Pete Gray (Keith Carradine) in “A Winner Never Quits” (1986)

= Pete Rose (Tom Sizemore) in “Hustle” (2004)

No. 15:

= Jimmy Chitwood (Maris Valainis) in “Hoosiers” (1986). Valainis only has four lines in the movie, including “I’ll make it.”

= Larry Kelly (Robert Young) in “Death on the Diamond” (1934)

= Bruce Pearson (Robert DeNiro) in “Bang The Drum Slowly” (1973)

= Jack Parkman (David Keith) in “Major League II” (1994)

No. 16:

= Charlie Tyler (Joe Kapp) in “Two Minute Warning” (1976)

= Shane Falco (Keanu Reeves) in “The Replacements” (2000)

= Seth Maxwell (Mac Davis) in “North Dallas Forty” (1979)

= Dean Youngblood (Rob Lowe) in “Youngblood” (1986)

= Jack Hanson (Dave Hanson) in “Slap Shot” (1977)

= Joe Pendleton (Warren Beatty) as a Rams quarterback who makes it to the Super Bowl in “Heaven Can Wait” (1978)

No. 17:

= Ron Catlan (Charlton Heston) as quarterback for the New Orleans Saints in “Number One” (1969) (Thanks to Michael Weinreb’s Throwbacks.substack.com post on this film that notes New York Times critic Howard Thompson wrote the movie offered “one of the most interesting and admirable performances of (Heston’s) career.”

= Doug Remer (Matt Stone) in “BASEketball” (1998)

= Brad McQuade (Channing Tatum, as officer Jenko) in “22 Jump Street” (2014) as a QB for Metro City College

= Steve Hanson (Steve Carlson) in “Slap Shot” (1977)

No. 18:

= Jeff Hanson (Jeff Carlson) in “Slap Shot” (1977)

= Paul Crewe (Adam Sandler) in “The Longest Yard” (2005)

= Jeff Hanson (Jeff Carlson) in “Slap Shot” (1977)

= Paul Crewe (Adam Sandler) in “The Longest Yard” (2005)

= Happy Gilmore (Adam Sandler) wearing a Boston Bruins NHL sweater in “Happy Gilmore” (1996) and “Happy Gilmore 2” (2025)

= Mel Clark (Tony Danza) in “Angels in the Outfield” (1994)

= Steve Nebraska (Brendan Fraser) in “The Scout” (1994)

No. 19:

= Jack “Cap” Rooney (Dennis Quaid) in “Any Given Sunday” (1999)

= Matty Reynolds (Owen Wilson) as a Washington Nationals pitcher in “How Do You Know” (2010)

No. 20:

= Derek Sutton (Patrick Swayze) in “Youngblood” (1986)

= Gavin Grey (Dennis Quaid) in “Everybody’s All-American” (1988)

No. 21:

= Stan Ross (Bernie Mac) in “Mr. 3000” (2004)

= Ben Williams (Matthew McConaughey) in “Angels in the Outfield” (1994)

= Jimmy Piersall (Anthony Perkins) in “Fear Strikes Out” (1957)

No. 22:

= Paul Crewe (Burt Reynolds) in “The Longest Yard” (1974)

= Quincy McCall (Omar Epps) as a Crenshaw High and USC basketball player in “Love and Basketball” (2000)

= Juwanna Mann (Miguel Nunez Jr.) playing for the WUBA’s Banshees as Jamal Jeffries in “Juwanna Mann” (2002)

= William Gates in “Hoop Dreams” (1994)

= Doris Murphy (Rosie O’Donnell) in “A League of Their Own” (1992)

= Bill Murray (as himself) for the Tune Squad in “Space Jam” (1996)

= Dizzy Dean (Dan Dailey) in “The Pride of St. Louis” (1952)

No. 23:

= Kit Keller (Lori Petty) in “ “A League of Their Own” (1992)

No. 24:

= Roger Dorn (Corbin Bernsen) in “Major League” (1989)

No. 25:

= Monty Stratton (James Steward) in “The Stratton Story” (1949)

No. 26:

= Ricky Bobby (Will Ferrell) driving the Wonder Bread NASCAR ride in “Talladega Nights” (2006)

No. 27:

= Gus Sinski (John C. Reilly) in “For Love of the Game” (1999)

No. 28:

= Jarvis Edison (Jason Bateman) in “Necessary Roughness” (1991)

= “Happy” Jack Jackson (Dan Dailey) in “The Kid from Left Field” (1953)

No. 29:

= Wacky Waters (Eddie Albert) in “Ladies’ Day” (1943)

= Grover Cleveland Alexander (Ronald Regan) in “The Winning Team” (1952)

No. 30:

= Jim Craig (Steve Guttenberg) in “Miracle on Ice” (1981)

= Jim Craig (Eddie Cahill) in “Miracle” (2004)

= Benjamin Franklin Rodriguez/aka “Benny The Jet” (Mike Vitar) in “The Sandlot” (1993). He is in a Dodgers’ No. 30 uniform at the end of the film, with Maury Wills, who actually wore No. 30, coaching third base. Rodriguez may still be the last Dodger to have a true steal of home plate. Also to be accurate, the player wearing No. 30 for the Dodgers in the film is Vitar’s older brother, Pablo, according to Baseball Reference.

No. 31:

= Chuck Smith (Alex English) playing for the Boston Celtics in “Amazing Grace and Chuck” (1987)

= “T-Rex” Pennebaker (Brian J. White) in “Mr. 3000” (2004)

No. 32:

= Monica Wright (Sanaa Latham) as a Crenshaw High and USC women’s basketball player in “Love and Basketball” (2000)

= Nick Bonelli (Tony Curtis) in “All American” (1953)

= Chet “Rocket” Steadman (Gary Busey) in “Rookie of the Year” (1993)

No. 33:

= Charles Jefferson (Forest Whitaker) in “Fast Times at Ridgemont High” (1982)

= Monica Wright (Sanaa Lathan) as a USC women’s basketball player in “Love and Basketball” (2000)

= Julian Washington (LL Cool J) in “Any Given Sunday” (1999)

= Jackie Moon (Will Ferrell) in “Semi-Pro” (2008) Noted: Ferrell was said to have been the captain of his basketball team at University High in Irvine as well as a kicker for the football team and a soccer player.

= Stef Djordjeciv (Tom Cruise) in “All The Right Moves” (1983)

= Greg “Goldie” Goldberg (Sean Weiss) in “The Mighty Ducks” (1992), “D2: The Mighty Ducks” (1994), “D3: The Mighty Ducks” (1996)

= Bobby Rayburn (Wesley Snipes) in “The Fan” (1996) Rayburn also spends time in the film trying to get No. 11 from teammate Juan Primo, who doesn’t give it up, and Rayburn goes into a slump.

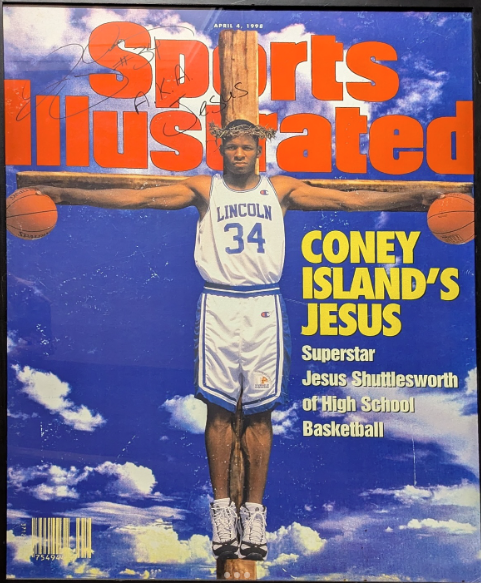

No. 34:

= Jesus Shuttlesworth (Ray Allen) in “He Got Game” (1998)

= Lou Brown (James Gammon), Cleveland Indians manager in “Major League” (1989)

No. 35:

= Moses Guthrie (Julis Erving) in “The Fish that Saved Pittsburgh” (1979)

No. 37:

= Ebby Calvin “Nook” LaLoosh (Tim Robbins) in “Bull Durham” (1988)

= Lee (Bill Lee) in “Eephus” (2024)

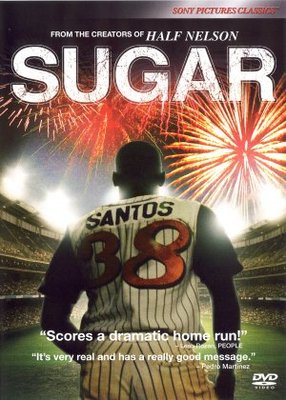

No. 38:

= Miguel “Sugar” Santos (Algenis Perez Soto) in “Sugar” (2008)

= Bill Lee (Josh Duhamel) in his Longueuil Senators beer league baseball jersey in “Spaceman” (2016)

No. 39:

= Larry Hockett (Robert Wuhl) as the Durham pitching coach in “Bull Durham” (1988)

No. 40:

= Kent Stock (Sean Astin) in “The Final Season” (2007)

= Max “Hammer” Dubois (Dennis Haysbert) in “Mr. Baseball” (1992)

= Gayle Sayers (Billy Dee Williams) in “Brian’s Song” (1971)

No. 41:

= Brian Piccolo (James Caan) in “Brian’s Song” (1971)

No. 42:

= Jackie Robinson (Chadwick Boseman) in “42” (2013)

= Scott Howard (Michael J. Fox) in “Teen Wolf” (1985)

No. 44:

= Forest Gump (Tom Hanks) as the Alabama kickoff returner in “Forest Gump” (1994)

= Reggie Jackson (as himself) in “The Naked Gun: From the Files of Police Squad!” (1988)

= Luther “Boom Boom” Jackson (Ron Rich) in “The Fortune Cookie” (1966). Jackson runs over cameraman Harry Hinkle (Jack Lemon) and sets brother in law Willie Gingrich (Walter Matthau) out to get him insurance money. At Municipal Stadium in Cleveland, 1966.

= Joe Cooper (Trey Parker) in “BASEketball” (1998)

= Steve Novak (John Derek) in “Saturday’s Hero” (1951)

No. 45:

= Rudy Ruettiger (Sean Austin) in “Rudy” (1993)

= Boobie Miles (Derek Luke) in “Friday Night Lights” (2004) (Miles’ number is actually 35)

No. 49:

= Jim Bowers (Jonathan Silverman) in “Little Big League” (1994)

No. 50:

= Neon Bodeaux (Shaquille O’Neal) in “Blue Chips” (1994)

No. 54:

= Jack Elliott (Tom Selleck) in “Mr. Baseball” (1992)

No. 55:

= Kenny Powers (Danny McBride) for various teams in “Eastbound & Down” HBO series (2009 to 2013)

No. 58:

= Luther “Shark” Lavay (Lawrence Taylor) in “Any Given Sunday” (1999)

No. 62:

= Ricky Bobby (Will Ferrell) driving his new “ME” car in “Talladega Nights” (2006)

No. 63:

= Jim Morris (Dennis Quaid) in “The Rookie” (2002)

No. 69:

= O.W. Shaddock (John Matuzak) in “North Dallas Forty” (1979)

= Douglass Menachem “Doug The Thug” Glatt (Seann William Scott) in “Goon” (2011)

= Ed “Bull” Lawrence (John Goodman) in “Everybody’s All-American” (1988)

No. 74:

= Michael Oher (Quinton Aaron) in “The Blind Side” (2009)

No. 77:

= Darren Roanoke (Romany Malco) as a Toronto Maple Leafs player in “The Love Guru” (2008)

No. 78:

= Sinbad (Andre Krimm) in “Necessary Roughness” (1991)

No. 83:

= Vince Papale (Mark Walhberg) in “Invincible” (2006)

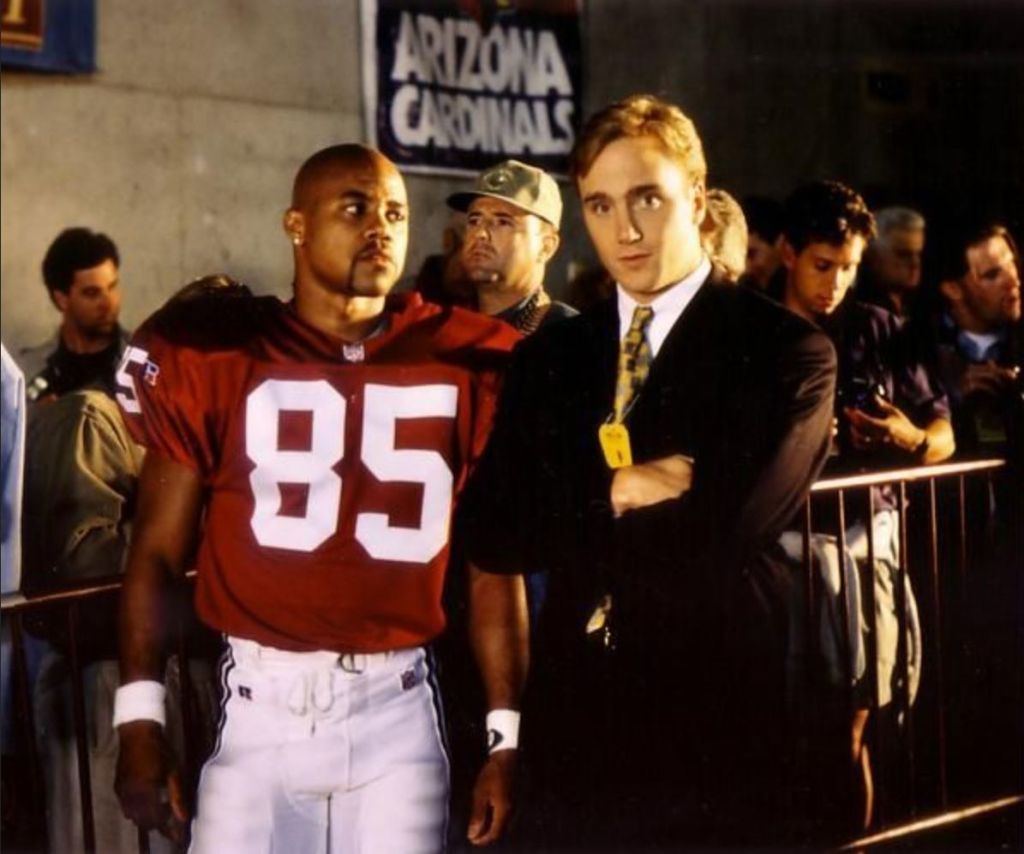

No. 85:

= Rod Tidwell (Cuba Gooding Jr.) in “Jerry Maguire” (1996)

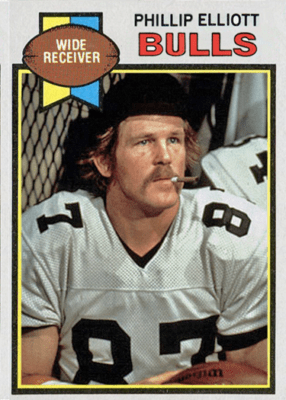

No. 87:

= Phillip Elliott (Nick Nolte) in “North Dallas Forty” (1979)

= Terry Brogan (Jeff Bridges) as a Dallas Outlaws tight end in “Against All Odds” (1984)

No. 94:

= Derek Thompson (Dwyane Johnson) as a hockey player in “Tooth Fairy” (2010)

No. 96:

= Charlie Conway (Joshua Jackson) in “The Mighty Ducks” (1992), “D2: The Mighty Ducks” (1994), “D3: The Mighty Ducks” (1996)

No. 99:

= Irwin “Fletch” Fletcher (Chevy Chase) in “Fletch” (1985) and “Fletch Lives” (1989)

= Adam “Banksy” Banks (Vincent Larusso) in “The Mighty Ducks” (1992), “D2: The Mighty Ducks” (1994), “D3: The Mighty Ducks” (1996)

= Jack Dundee (Robin Williams) in “The Best of Times” (1986)

Who else wore No. 99 in SoCal sports history? Make a case for:

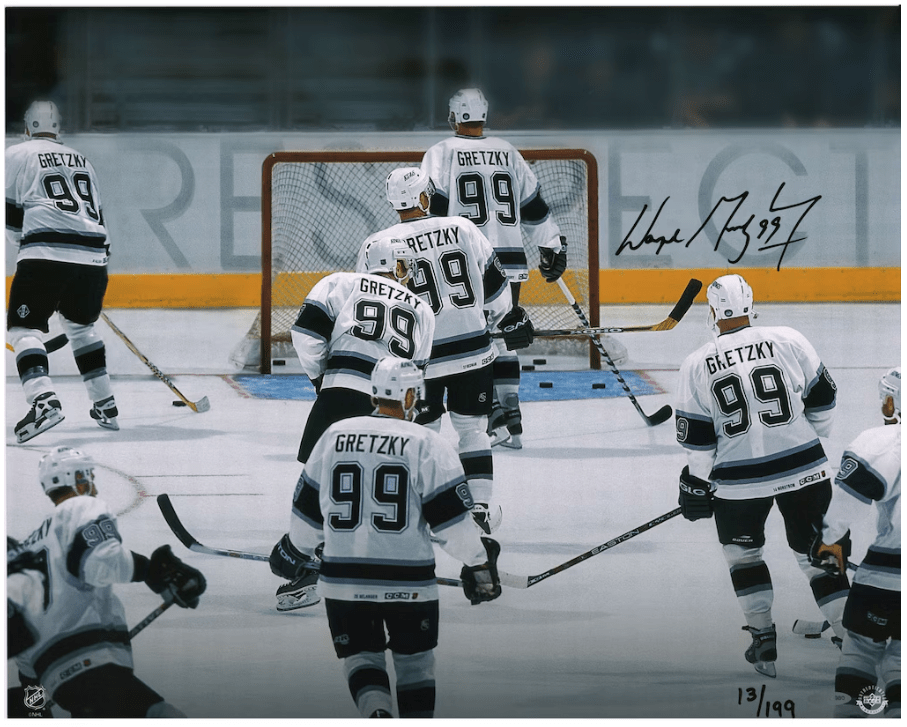

Wayne Gretzky, Los Angeles Kings center (1988-89 to 1995-96):

Wayne Gretzky’s wizardry was in his appreciation of geometry.

“People talk about skating, puck handling and shooting,” he once said, “but the whole sport is angles and caroms, forgetting the straight direction the puck is going, calculating where it will be diverted, factoring in all the interruptions.”

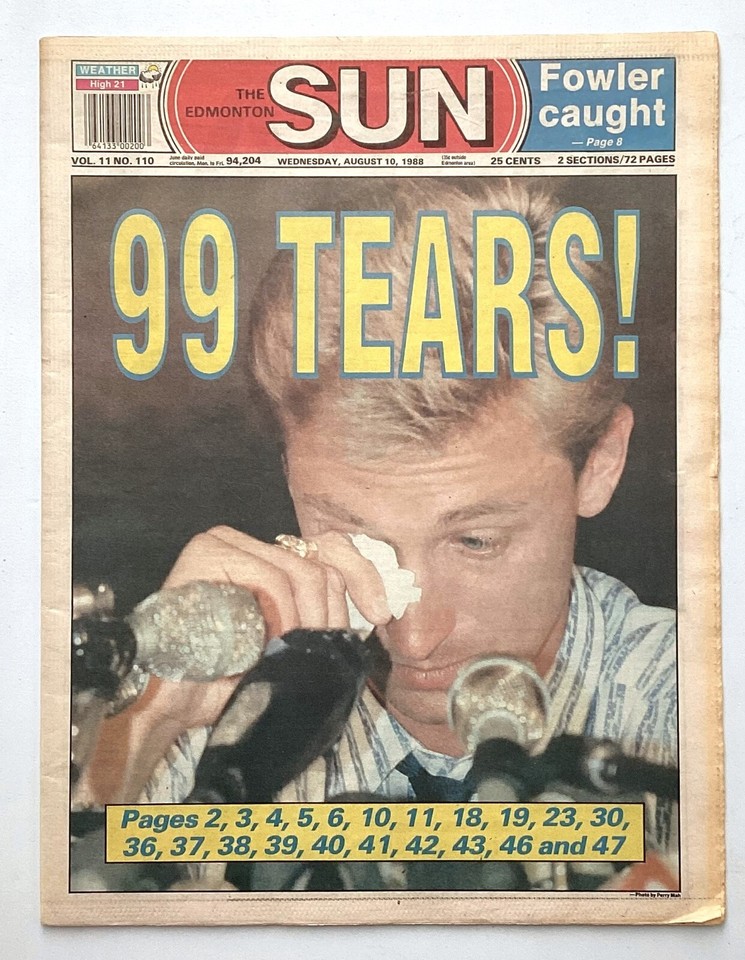

His eight seasons with the Los Angeles Kings may have resulted in just one trip to the Stanley Cup Final — the franchise’s first, in 1993, and also the last time a Canadian team won it as of 2025. He had won four championships with the Edmonton Oilers in the nine seasons prior to coming to Hollywood. But the acute angle to his arrival in L.A. was perpendicular to how the game of hockey became far more fashionable and celebrity driven than it had been since the team’s existence 20 years earlier. There is even a rare accurate “AI Overview” of what happened on Aug. 9, 1988 if the date is Googled: The idea that “the biggest trade in hockey” happened “due to its historical significance and the star power involved.” History.com even has an entry for it.

It was referred to in headlines as a “Kings’ Ransom” (which became the title of the first ESPN 30-for-30 documentary in 2009) when Edmonton agreed to send Gretzky to Los Angeles Kings with Marty McSorley and Mike Krushelnyski in exchange for Jimmy Carson, Martin Gelinas, three first-round picks and $15 million — even if most people stopped listening to the details after trying to process the first few words of that previous transactional sentence.

The nation of Canada lost its collective minds. The city of L.A. thought, hey, this could be fun.

The 27-year-old, in-his-prime, holder of some 50 NHL records had won eight Hart Trophy/MVP Awards, had been hijacked by a Kings owner who may have turned out to be a financial fraud, but … you’re welcome.

As a member of the Kings, Gretzky was able to break Gordie Howe’s all-time goal-scoring record (Gretzky had taken No. 99 as a way to honor Howe’s No. 9). Gretzky’s landing in L.A. is also said to have directly resulted in the NHL adding a franchise in Anaheim and San Jose, and a movement for teams to relocate in the Southwest (Arizona, Dallas, Salt Lake City).

In 2000, the NHL announced Gretzky’s No. 99 would never be worn by another player. The Kings threw up a statue of him outside Staples Center and a banner honoring No. 99 hangs in the arena (aside from the No. 99 set aside for George Mikan, the Minneapolis Lakers center who played before the team moved to L.A.)

Gretzky’s 583 games as a King included another MVP in his first season (a league best 114 assists to go with 54 goals), leading the league in assists four times, setting a franchise record of 1.25 assists per game (Marcel Dionne is second at 0.82), twice voted the Lady Bing sportsmanship award, scoring 246 goals (currently eighth-best in the franchise), recording 672 assists (currently third best), posting 918 points (currently fifth best), and scoring six hat tricks.

Three interesting takeaways. He never led the Kings to a Stanley Cup title (only the finals, once in 1993), he got to host “Saturday Night Live” in 1998 (with the Fine Young Canibals as the musical guests) and when the Kings traded him to St. Louis in February of 1996, it didn’t seem to be all that shocking any more. Gretzky lasted just 31 games with the Blues and went to a rest home after that to play for the New York Rangers.

When Gretzky retired in 1999 at 38, he held or shared 61 NHL records, and still holds nearly all of them. Except career goals. So be it. That was never one of Gretzky’s career goals anyway.

Aaron Donald, Los Angeles Rams defensive tackle (2014 to 2023):

In Joe Posnanski’s 2024 book, “Why We Love Football: A History in 100 Moments,” Aaron Donald takes up Chapter 100 to focus in on one play that may have summed up the player who wore No. 99 for the Rams over 10 seasons. It’s the end of the 2021 season, less than a minute left in Super Bowl LVI, as the Los Angeles Rams held a 23-20 lead over the Cincinnati Bengals at SoFi Stadium in Inglewood. Bengals quarterback Joe Burrow, trying to get his team into field goal range, handed the ball to running back Samje Perine on third-and-1. Perine, all 240-pounds of him, heads for the first down line but Donald, at 6-foot-1 and 280 pounds, spun around Cincinnati’s 6-foot-4, 315-pound right guard Hakeem Adenji on the snap and then grabbed Perine from behind. “Nobody is that strong without CGI,” wrote Posnanski. “Only Aaron Donald is, in fact, that strong.” On the broadcast, NBC’s Al Michaels said: “That is why people say he’s the best layer in the league.”

Then, on fourth-and-1, one last gasp for the Bengals. Burrow took the snap in the shotgun. The Bengals planned to have two blockers on Donald. Instead, Donald left behind left guard Quinton Spain, sped past center Trey Hopkins, got behind Burrow and brought him down.

Donald, who came back for an abbreviated 2022 season (11 games), and played a full 16 in 2023 before retiring at age 32, piled up 10 Pro Bowl selections, eight All-Pro picks, was AP First-Team eight times, Defensive Player of the Year three times, and a member of the Hall of Fame’s All-2010 Team.

After his first two years with the franchise in St. Louis, picked No. 13 overall in the 2014 NFL Draft out of Pittsburgh, the man on Instagram known as aarondonald99 had 111 sacks, 543 tackles, 340 solo tackles, 176 tackles for losses, 260 quarterback hits, 24 forced fumbles, seven fumble recoveries and a safety in 154 games.

Manny Ramirez, Los Angeles Dodgers outfielder (2008 to 2010):

“Manny and Los Angeles fell for each other like teenage lovers,” wrote Jean Rhodes and Shawn Boburg in “Becoming Manny: Inside the Life of Baseball’s Most Enigmatic Slugger” a 2009 authorized biography of Ramirez. “Accustomed to celebrities, and hardly as diehard about their jocks as Bostonians, South Californians granted him relative privacy when he left the park. Manny rewarded Dodgers fans with gaudy numbers and a division title.”

It was, for a brief time, “Mannywood” in left field at Dodger Stadium. Seats in Sections 51 to 53 in the corner by the bullpen were once selling by the team at $99. More than 14,000 Ramirez T-shirts and 500 authentic No. 99 jerseys were sold by season’s end in 2008.

The Dodgers and general manager Ned Colletti took “Manny Being Manny” off the Boston Red Sox anxiety menu and worked a deal at the July 31, 2008 trade deadline (outmaneuvering the Angels). The Dodgers send four non-descript players to Pittsburgh, allowed the Pirates to send outfielder Jason Bay to Boston, and then had Boston give ship Ramirez to L.A. as well as $7 million to cover his salary, aware Ramirez could be a free agent when the season was over.

Ramirez couldn’t get his familiar No. 24, already been retired for Walter Alston. He asked for Nos. 11 and 34, but the Dodgers had them set aside (for Manny Mota and Fernando Valenzuela). Ramirez asked clubhouse manager what was left. Poole suggested 28. Then 66 (later to be given to Yasiel Puig). The flipped it and settled on 99.

Ramirez, a 12-time All-Star, two-time World Series champ and nine-time Silver Slugger with more than 500 homers, arrived for the final months of the ’08 season, 53 games, and created a slash line of .396/.489/1.232 with 17 homers and 53 RBIs. In the eight games that made up the Dodgers’ ’08 playoffs, Ramirez was 13 for 25 with four homers and 10 RBIs.

In spring of ’09, the Dodgers signed Ramirez to a two-year, $45 million deal. But on May 7 of that season, after having posted a .348 batting average with six homers and 20 RBI, he was handed a 50-game suspension for violating the MLB’s PED policy. Returning in July, Ramirez hit a pinch-hit grand slam on his bobblehead night, but he had a clout of doubt over him again as he was outed again in a New York Times investigation into steroid use, along with Barry Bonds, Sammy Sosa and David Ortiz. In the 2009 playoffs, spanning another eight games, Ramirez went 9 for 22 with a homer and 4 RBIs.

In both seasons seasons, the Dodgers fell one round short of the World Series appearance.

By 2010, Ramirez was on the disabled list three times, but still, at age 38, hitting .311 in 66 games. On the last day of August, the Dodgers put him on waivers, and the Chicago White picked him up for the last 24 games. He sputtered out with trips to Tampa Bay, then signings-and-releasing with Oakland, Texas and the Chicago Cubs by 2014 at age 42.

All in all, the Dodgers-Ramirez quirky marriage that produced a .322 batting average, 44 homers, 156 RBIs in 223 games. And a 6.3 WAR. His career stats — 555 homers, 1,831 RBIs, .312 batting average, 69.3 WAR — are in line with Frank Thomas, Vlad Guerrero and David Ortiz, but Ramirez has yet to get close at all in voting to join them in the Hall of Fame.

“Through a certain prism, Manny can also be viewed as the most potent slugger in Dodgers history,” wrote Ryan Ferguson. “Regardless of the subsequent controversy, for three glorious months in 2008, there was no greater hitter on planet Earth than Manny, and he wore Dodger blue. That legacy cannot be accurately quantified, because it tugged at the heartstrings while also exploding calculators. Manny Ramírez was a force of nature in Los Angeles, even if the star eventually collapsed in on itself, like a startling supernova above the Santa Monica hills. Manny Ramírez was a law unto himself, but the Dodgers used that law to great effect, and they continue to do so today, as their winning culture becomes a paragon of baseball and business.”

Hyun Jin Ryu, Los Angeles Dodgers pitcher (2013 to 2019):

After seven seasons with the Kanwha Eagles, as well as pitching for China in the 2008 Olympics, Ryu became the first player from the KBO to join an MLB team when the Dodgers won the bidding for the rights to the 6-foot-3, 250-pound left-hander. The Dodgers posted a $25.7 million bid to negotiate, and then gave him a six-year, $36 million deal. A series of “firsts” followed — the first South Korean starting pitcher in an MLB post-season game (2013), the first South Korean to start a game in the World Series (2018), the NL’s starting pitcher in the 2019 All Star Game in a season where he led all of MLB with a 2.32 ERA and was second in the Cy Young voting, starting the season with a 1.26 ERA through his first 14 games. Ryu signed a four-year, $80 million free agent deal to go to Toronto, and returned to South Korea to pitch in 2024 for eight years and 17 billion won, the largest contract in KBO history. Ryu is so revered in South Korea that no other Hanwha Eagles player wore his No. 99 since he went to the Dodgers in 2012.

Denis Bouanga, LAFC forward (2022 to present):

The star from France signed with the LAFC and became the first player in MLS history to score 20 goals in three straight seasons when he had a hat trick against Real Salt Lake on Sept. 21, 2025. The list of team and individual awards Bouanga accrued since his arrival from Saint-Étienne in August 2022: Two All Star appearance, the 2022 MLS Cup, a Golden Boot and Best XI honors in both MLS and Concacaf Championship Cup.

Tim Ryan, USC football defensive tackle (1986 to 1989):

After starting the ’86 season opener as the first true freshman to do so in eight years, the 6 feet 4 1/2 inches and 270 pound Ryan became a two-time All-American and left USC as its all-time leading tackler, setting a record for sacks in a career with 20. The team captain was also a starter in three Trojan Rose Bowl games.

Mike Patterson, USC football nose tackle (2001 to 2004)

Out of Los Alamitos High, Patterson (6-foot-1, 300 pounds) became a starting All-American nose tackle on Trojan teams that claimed two national championships. A first-round pick by Philadelphia, he has the franchise’s longest fumble return — 98 yards for a touchdown in 2006.

Tony Corrente, NFL official (1995 to 2021):

A social sciences teacher at La Mirada High, Corrente put in 26 seasons as an NFL ref until he retired because of throat cancer. He started officiating games on the high school and junior college level in Long Beach and San Gabriel Valley in the early 1970s, moved up to NCAA games in the PCAA, WAC and Pac-12, and caught on as a back judge in the NFL in 1995. His 13 NFL post-game assignments included three AFC and NFC title games and as the referee in Super Bowl XLI.

We also have:

Kenyon Coleman, UCLA football defensive end (1997 to 2001)

Jerry Tillery, Los Angeles Chargers defensive lineman (2019 to 2022)

Anyone else worth nominating?

Here is where things can get a little problematic wearing No. 99. Is this the same person? One is at Dodger Stadium from 2022. The other is at Glendale, Ariz., spring training in 2025.

2 thoughts on “No. 99: Carlos Estéves, Charlie Sheen, and Ricky Vaughn”