This is the latest post for an ongoing media project — SoCal Sports History 101: The Prime Numbers from 00 to 99 that Uniformly, Uniquely and Unapologetically Reveal The Narrative of Our Region’s Athletic Heritage. Pick a number and highlight an athlete — person, place or thing — most obviously connected to it by fame and fortune, someone who isn’t so obvious, and then take a deeper dive into the most interesting story tied to it. It’s a combination of star power, achievement, longevity, notoriety, and, above all, what makes that athlete so Southern California. Quirkiness and notoriety factor in. And it should open itself to more discussion and debate — which is what sports is best at doing.

The most obvious choices for No. 90:

= Larry Brooks, Los Angeles Rams

= Mike Wise, Los Angeles Raiders

The most interesting story for No. 90:

Andrei Voinea, California School of the Deaf Riverside football center, offensive lineman, tight end (2021 to 2022)

Southern California map pinpoints:

Riverside, Burbank

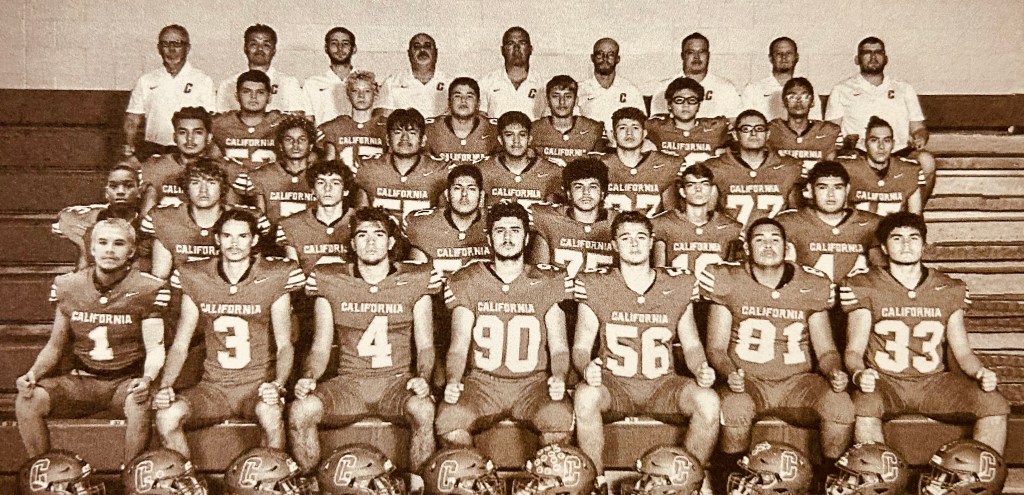

In the 2022 team photo of the California School of the Deaf Riverside high school football squad, No. 90 Andrei Voinea is front and center.

The starting center on the offensive line by season’s end, Voinea may not have been the most athletic or talented of a team that would go on to win a championship, but he was the biggest and perhaps the quickest learner, with a computer science mind and newfound appreciation for how he could converse with classmates.

The position of center who starts the play is vital, not only in an eight-man football alignment where the line works harder on protection after the snap. But, as the name of the school indicates, unique communicate is needed before and after the snap. It’s a skill set that starts in the school’s classrooms, social networking, and transfers to the football team’s collective success.

That photo also shows Trevin Adams, No. 4, the team’s quarterback/linebacker captain, next to Voinea. Adams is the son of the head coach, Keith Adams, up there in the back row, five in from the left. Trevin’s younger brother, freshman Kaden, was his backup at quarterback.

Jory Valencia, No. 3, is next to Adams, the team’s 6-foot-3 senior captain at wide receiver and cornerback. His grandfather Seymour Bernstein came to the school in 1958 and coached football. His parents, Jeremias and Scarlett, both attended CSDR and excelled in sports, as did his older brother Noah and his uncles Joshua Valencia, Jonathan Valencia, Steve-Valencia-Biskupiak and Ethan Bernstein.

Next to Valencia is Felix Gonzales, No. 1, the team’s most outstanding player and another senior captain. By the end of the season, Gonzales was recovering from a leg injury and couldn’t make the team picture. The school deftly edited him in digitally for this team shot.

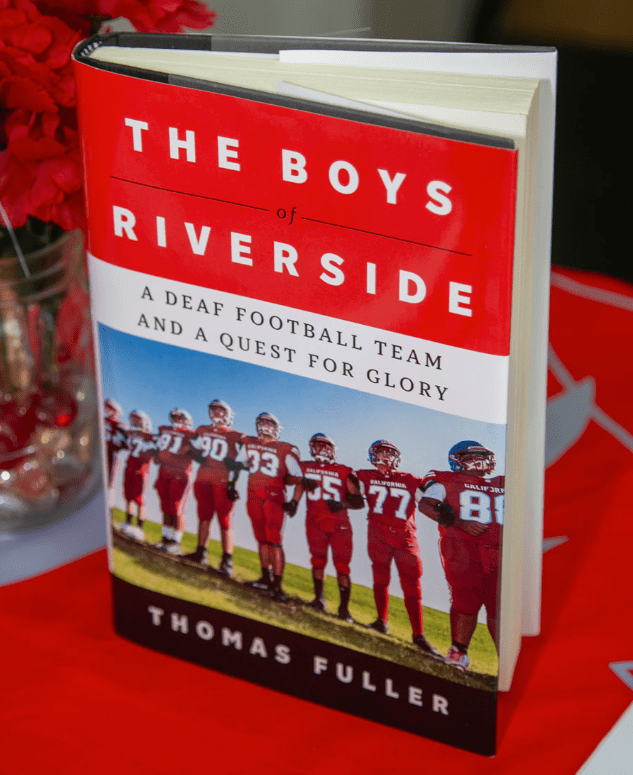

All of them and more make up the central casting of the 2024 book, “The Boys of Riveside: A Deaf Football Team And a Quest for Glory.” Note on the cover: Voinea, fourth in from the left, linking arms with teammates.

New York Times writer Thomas Fuller introduces Voinea and his teammates who, coming out of a COVID confusion that shutdown all the school’s sports, happened to be at the right place at the right time to make California School of the Deaf Riverside a rather improbable California Intercollegiate Federation (CIF) Southern Section champion.

“It was so quintessentially American,” Fuller, struck by the students’ perseverance, eventually described it to People Magazine. “A team that had endured seven decades of losing seasons was now beating the pants off of all their opponents.”

Listen as these Cubs roar.

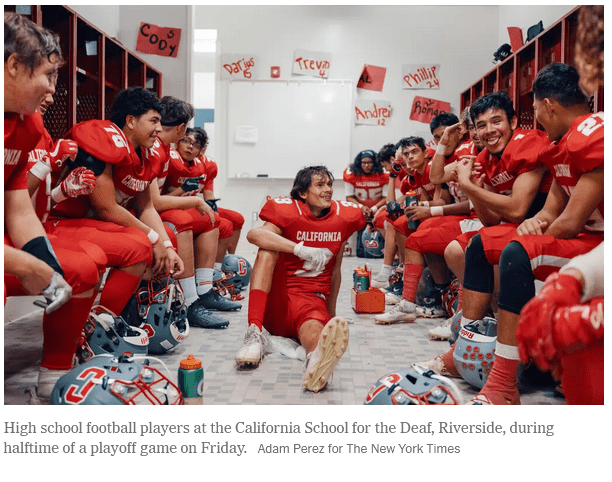

On the wall behind them are posters of players’ names and numbers. One of them is “Andrei 12.”

Voinea wore No. 12 as a junior (as well as when the team was on the road and needed a white jersey) because “Tom Brady was my favorite player in the NFL,” he said.

He wore No. 90 more in his senior year, admitting “it sounds bigger and more fitting for my size, considering most of the big guys in the NFL chose higher jersey numbers.”

Below: A photo of Voinea wearing No. 12 during a game at Avalon High on Catalina Island.

A year earlier, in 2021, the Cubs made noise as the first in the school’s 68-year history to advance to a section championship game. Scores of local and national media outlets came along for the ride and a storyline that was too good to pass on — a team of deaf players, at a school with more than 50 years of losing seasons, rose up out of COVID and did something remarkable.

Even though CSDR lost that title game, 74-22, to Faith Baptist of Canoga Park, the 2022 team went all the way on a 12-0 run, avenging the defeat with a convincing 80-26 win over the same Faith Baptist program.

Andrei Voinea was hardly the center of attention on either of the CSDR ’21 and ’22 football teams — just the biggest.

At 6-foot-4 and 240 pounds, Voinea shot up between his junior and senior seasons, just trying to figure out what shoe sizes to wear, let alone a proper fitting jersey.

Voinea explained to us in an e-mail interview how this came to be:

“I grew up in mainstream elementary and middle school. I was one of the only deaf students among thousands of hearing peers, so I had to rely on my interpreters for access to education. A casual and direct conversation with others was nearly impossible, often feeling like I was talking to my interpreter instead of the classmate or teacher.

“When I was young, I grew up playing soccer and baseball in local leagues with no other deaf teammate or opponent. There was also no interpreter, which makes it more challenging for me to learn new skills and plays. Most of the time, when my coach tried to train or give me advice, they’d have to use simple gestures, just hoping I’d understand.

“Since my elementary and middle school didn’t have an actual sports team, these league sports were my real training ground where I learned a lot of new skills that applied to my football career in CSDR.”

Voinea transferred to CSDR in the eighth grade.

“Everything changed,” he said.

To that point, Fuller explained in the book about how Voinea, living with his parents in Burbank, frequently traveled to see family in their native Romania. It lead to living a “split-screen life, between the freeways, the smog and the conveniences of Los Angeles, and the poor rugged countryside of his grandparents’ subsistence farming in Eastern Europe.” The trips to Voinea’s grandparents’ farm for long vacations, living among apple orchards, gave him the experience of helping tend to their animals.

At CSDR, starting in middle school, Voinea tried cross country, wrestling, track and field, baseball and basketball. As a football player, he was considered “too nice” by his varsity line coach, Michael Mabashov. But for the first time, Voinea was on a team that was 100 percent deaf, and had deaf coaches.

Even if Voinea admitted he wasn’t getting a lot of playing time because his athletic skills “weren’t polished,” the fact he could “chat with nearly everyone on the campus was overwhelming to me in the best way.” Nearly half of the Riverside school’s 51 high school boys were on the varsity football team.

As a freshman, Voniea wasn’t into football yet. As a sophomore, all sports were shut down because of the pandemic. As a junior, because of Voinea’s growth spurt, a friend recommended he try varsity football.

“My role wasn’t as a center until one day when we had to practice inside the gym because it was raining,” Voinea explained. “During the practice, one of my friends asked me to snap the ball for him — my ball snapping was pretty good enough to be a back-up center. So, it pretty much went from there, I practiced as a center every single day improving my snap accuracy with our coaches.”

Coach Adams gave him starting opportunities, but Voinea said “usually I didn’t play well because of immense pressure that I wasn’t used to, so I usually got replaced. I remember all the embarrassment and frustration in myself after failing the snap or getting replaced — but that is what improves and thrives me.”

About to turn 17, Voinea was also a “formidable video game programmer in his spare time,” Fuller explained in the book. Voinea designed animation for games on the Roblox platform, popular with preteens. He did animation for parts of the game ESCAPE Miss Marie’s Library, one of the most popular on the platform.

“At times, he saw real life through the lens of his video game programming,” Fuller wrote of Voinea. “In football, it helped him conceptualize plays.”

Voinea told Fuller: “I feel like I am looking at the field from above, and I can move the pieces around.”

The California School for the Deaf in Riverside, which educates deaf and hard-of-hearing students from 11 counties in Southern California covering kindergarten through 12th grade, didn’t field itss first varsity football team until in 1956, three years after its initial graduating class.

By 1965, it had the CIF 1A-Southern Section Player of the Year and Riverside County Player of the Year in Jerry Moore, a senior fullback who ran for 1,127 yards and 18 touchdowns, averaging eight yards a carry. For his career, Moore ran for 3,630 yards and 53 touchdowns in 25 games. He remains a benchmark for players in the deaf community.

The Cubs won league titles in 2004 and ’05, but they suffered first-round playoff losses in both those seasons, as well as in 1988, 1994, 1997 and 2009. The program had only nine winning seasons in its history before 2021.

Enrollment at the school was declining — it was at 165 in 2021. Three years earlier, in ’18, CSDR decided to switch from the traditional 11-man football to the 8-man format, used in more than 100 schools in California to accommodate smaller enrollments.

CSDR is about adaption. The school’s 63-acre campus, once surrounded by orange groves, is now framed by strip malls, freeways and fast-food restaurants. Yet it remains the only all-deaf public school serving the southern half of California.

In 2019, CSDR finally got a post-season win in Eight-Man Division II, 60-52 in overtime against St. Michael’s Prep of Silverado, and finished the season 5-5. Any momentum that generated was squashed during the 2020 COVID pandemic. The school, which housed many of its students on campus from Sunday evenings to Friday afternoons, had to cancel all sports for the 2020-21 school year during distance learning.

What also changed, Fuller noted, was the team’s leadership.

“Something about having all deaf players but also an all deaf coaching staff,” Fuller said. “No offense to Pete Lanzi (the late coach who led CSDR from 1961 through 1985 and is, in many respects, the godfather of the program), but having your coaches and your players being all deaf, I think that puts you even one notch higher in terms of communication, in terms of being able to leverage deafness.”

When a 2021 finally happened, Fuller wrote that some of the football players still were not fully housed as the sport was ready to resume. One player, Phillip Castandea, lived with his father in a car at a Target parking lot across the street from the campus.

The Cubs’ first big win was in late September 2021, a 66-57 win over Division I Calvary Chapel in Week 4. It was a serious surprise to those following the Division II Cubs.

“That started waking people up,” Valencia said. “It was a shock for us too.”

Fuller did his first reporting on the CSDR program for the New York Times in mid-November of that season, at a point when the team won 11 in a row. Someone from the California Department of Education sent him a tip to what was going on.

The New York Times coverage begat more of the local coverage, which begat more Southern California coverage.

CSDR’s trip a CIF title game in 2021 may have not only blindsided the team and players, along with the increased media coverage, but they adjusted to seeing themselves on ESPN, CNN, NBC, CBS and even PBS. An appearance on “The Kelly Clarkson Show” included receiving $25,000 to upgrade the school’s stadium.

Coach Adams knew it was good PR for the school, but said his players were getting a little tired of the redundancy of interviews.

The media also created the storyline about how the deaf players on the team could use that to its advantage. Almost as a super power. They relied on visual rather than verbal cues. They were rarely penalized for a false start because they didn’t move until the ball was snapped. They weren’t distracted by the cheers of the crowd or the trash talk of opponents.

Voinea explained how that worked from his center position:

“Since I cannot hear or see my quarterback use the snap signal, I’d have to look under my legs while holding the ball and wait for the quarterback to use the snap signal — usually a clap, but I preferred the leg stomp, since I’m tall. I’d then have a few seconds to look up at my opponent to study before snapping the ball quickly. If you watch the first two plays in the second championship game, you’ll see that Faith Baptist got penalized twice for false start because I just simply looked up after the signal clap and waited for a bit before snapping, which is pretty funny.”

For the 2021 title game, nearly 3000 people attended and, by this point, California governor Gavin Newsom included a budget proposal to build the school a new stadium and Disney came calling to discuss how the story could be made into a movie.

In that title game, Voinea came in midway through to be the starting center, as the two players on the depth chart ahead of him weren’t up to Coach Adam’s expectations.

“The amount of support from the crowd and the pressure got me locked in,” said Voinea. “I knew my team needed me. I ended up playing the entire time after halftime with high accuracy and power for the first time.

“Unfortunately we didn’t secure the victory and lost because most of our starters were injured and exhausted. (Coach Adams) told me he looked forward to my senior year and even said, ‘Wow, why didn’t you do that before?’ in the best way possible. I got a lot more confident after the championship game.”

Trevin Adams said most of the schools for the deaf around the country reached out to CSDR to offer their support after the title game loss.

“Hearing families with deaf family members were able to see our example, and that was probably the coolest thing, being able to really be a representative for the deaf community,” Trevin said. “I definitely feel like we have changed the perspective of realizing, like, ‘Deaf can do it.’”

The Cubs players, who had been invited by the Los Angeles Chargers to come to Inglewood’s SoFi Stadium for a game against the Minnesota Vikings in November of ’21, returned to the facility to serve as honorary captains prior to the 2022 Super Bowl as guests of the NFL.

They then watched the Los Angeles Rams win the championship against Cincinnati. They were inspired.

“I’ve played football since I was 7 years old,” Trevin Adams said. “My dream has not been attained yet, which is to be fully undefeated with a final championship title.”

The 2022 season started with a mission to claim the title of “best deaf football team in the country.” Week 3 was at the California School of the Deaf in Fremont, representing Northern California. Riverside traveled there and won, 54-6, in Week 3. The next week, CSDR hosted Indiana School of the Deaf and won again, 62-18. Florida School for the Deaf and Blind came to Riverside in Week 4. Riverside scored a program-high 84 points in a 76-point victory. CDSR was out to a 5-0 start through the end of September.

Media attention didn’t wane. The NFL Network, for example, showed up with Hall of Fame quarterback Kurt Warner to tape a series about the team’s “unfinished business.”

Fuller decided he would continue following the CSDR program after its 2021 title loss, sensing a book could be created with more context. The story of perseverance hadn’t ended, and many of the players returned as upperclassmen, like Voinea. As the team started another winning streak, the potential for another title game loomed as October turned into November.

In Week 6, however, CSDR star player Gonzales shattered his tibia, effectively ending his season. As the playoffs came closer, wide receiver Valencia had severe pneumonia and lineman Christian Jimenez broke his leg and was unable to walk.

Two days before the championship game rematch with Faith Baptist on Nov. 18, Jimenez convinced his parents and teammates to let him play wearing a brace.

“I still had that hunger and that drive. I wanted to feel that for one last time,” he said. “I gave my heart. I gave my all to it, for the Cubs.”

The Cubs ran off to a 42-12 lead by halftime. They also dominated the second half to cruise to an 80-26 victory.

But after his team’s loss, Faith Baptist star player A. C. Swadling channeled his inner-bully and screamed out: “You can hear me? You can hear me, right?”

The CSDR players could not, but they let it go. Fuller made sure to include that note in the book.

In the aftermath of the book’s success, Fuller added more perspective.

‘I really enjoyed the fact that this was happening in Riverside, because to me, the Inland Empire is an underdog,” Fuller told the Riverside Press-Telegram. “It’s not just the team that was an underdog. The Inland Empire does not get the respect that I think it deserves. People in L.A. don’t know that much about Riverside typically. People in Orange County might not know that much about Riverside. … I thought that it was perfectly fitting that this team came from a part of Southern California that is often looked down on … I think it’s fitting that what I think is the great American underdog story happens in an underdog town as well.”

The story wasn’t ready to end, apparently.

In 2023, CSDR repeated as CIF champions, defeating Faith Baptist again, this time 54-42. That team started the year 1-3. Sophomore Gio Visco was picked as the Division II player of the year, accounting for 36 touchdowns as a quarterback, runner, receiver and kick returner.

In 2024, CSDR won its third straight championship, taking down Flintridge Prep 44-42. The Cubs entered the fourth quarter trailing by a dozen points, rattled off 14 unanswered points in the quarter and also blocked a field goal. The 12-0 season was punctuated by outscoring their opponents 629-238.

“I am sure it inspires them because all of us face our own challenges so they can see someone who overcomes difficulties can help their hopes and motivation to keep striving towards their own goals,” coach Adams told the Riverside Press-Enterprise.

A bit for a fourth title ended in the first round of the 2025 playoffs with a 50-6 loss again to Faith Baptist, ending the Cubs season at 8-2. In the final game of the ’25 regular season, CSDR posted an 88-32 win over California Lutheran and scored 60 points or more seven times.

Championships speak volumes in the sports community. But it starts with the classroom setting.

Fuller said he asked Laura Edwards, the athletics supervisor at the school who is deaf and was born into a hearing family, about the debate over whether deaf children should attend mainstream institutions or all-deaf schools.

“Growing up as a deaf person I never went to a deaf school,” said Edwards, whose children attended CSDR at the time Voinea was a student. “It was a struggle to make friends. It was very lonely.”

At the Riverside campus, Edwards said she watched deaf students who transferred from mainstream institutions blossom.

“The communication barrier is eliminated and there is inclusion and social interaction,” she observed, noting Voinea as an example.

She added in a text to Fuller: “Our student athletes are the same as any other hearing students in terms of physical and mental skills and athletic talents. The only difference is they are Deaf.”

Fuller noted that Edwards capitalized the word “Deaf.”

“It’s not a typo,” she said. “We have a culture of our own.”

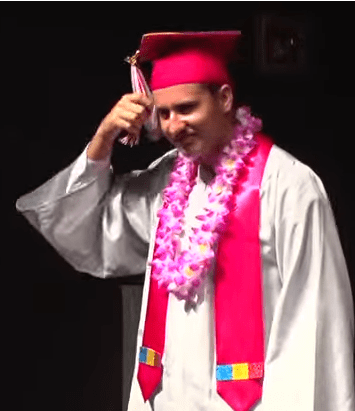

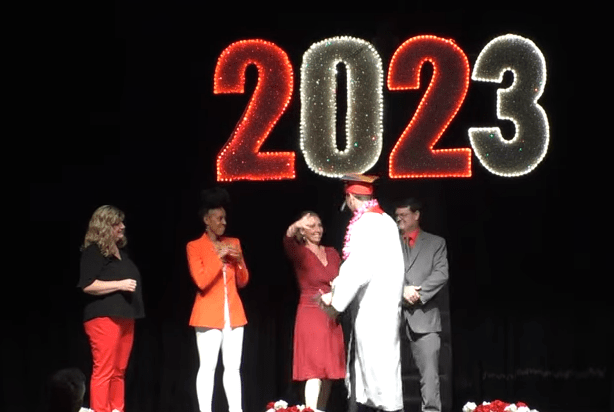

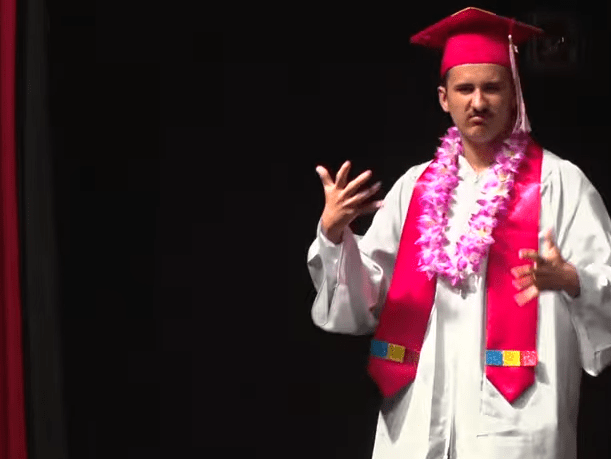

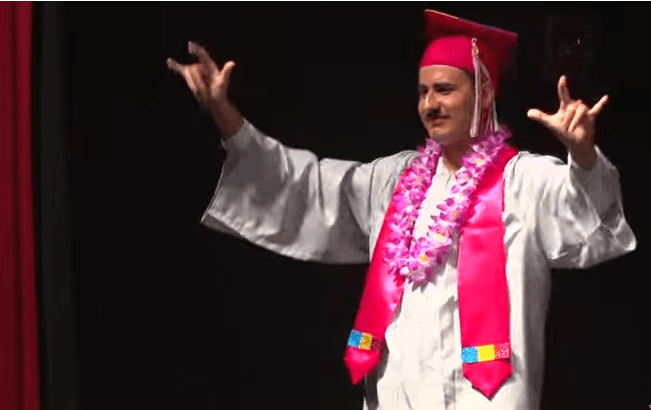

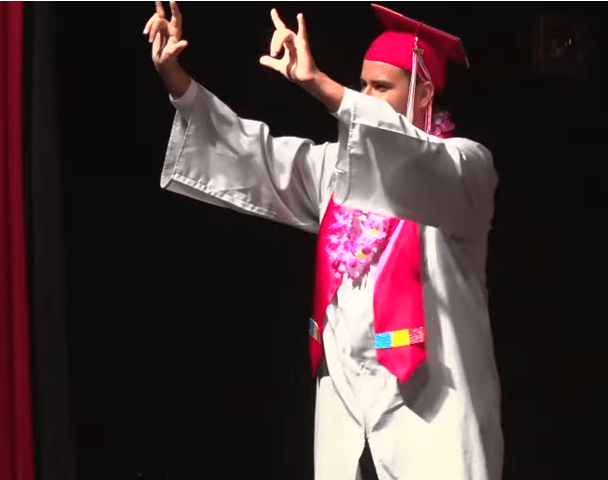

Fuller’s book, “The Boys of Riverside” was still a year from coming out when Voinea joined his classmates as the 2023 graduation.

Reflecting on Voinea’s time at CSDR, Coach Adams gave an honest assessment: “He was a great kid. Unfortunately, he is not athletic — even though he has nice size. But he always showed up and tried his best every day. I tried to find one bad thing about him — I can’t find anything at all.”

Voinea said transferring to CSDR “was the best decision I’ve ever made. I made hundreds of memories and even made a lot of friends. I got to experience all the emotions of being defeated in a championship game and then secured the championship for the first time in CSDR history. And even getting recognized by many people, communities, and governments.

“All of that was possible because I was in the right community where I feel relatable.”

So … about the theory that those who are deaf have learned a new superpower in how to navigate the world …

“I believe that deaf people have heightened visual senses, since we cannot hear our surroundings, we rely on looking around often to know more about our surroundings,” Voinea said. “From my experience, it’s very often for me to see people cross the street without looking around since they rely on hearing their surroundings, which isn’t the best idea.”

At graduation, Voinea made sure to tell the assembled, in sign language, how much he appreciated their support. Especially his parents.

The universal “I love you” sign was very easy to understand.

As a self-taught video game animator, Voinea told Fuller for his book that his goal at one point was to work for Disney, near the Burbank home where he still lives.

He also considered going either to Cal State Northridge or to National Technical Institute for the Deaf – Rochester Institute of Technology in New York.

Voinea now believes his self-taught abilities have made him focused less on a college campus experience for now and more on creating his own games on the Roblox platform — creating particles like explosions and flames, designing a graphical user interface for games, and learning all the necessary skills to create an entire game.

“I like to create horror and competitive games,” he said. “Usually horror games are my biggest challenge since they rely on sounds and audios a lot to scare players.”

Voinea isn’t scared about what lies ahead. He is still finding his voice amidst all that CSDR helped him discover.

“When I look to hire a freelance scripter to program my game, they’ll often ask to call or use voice chat to discuss the plan and tasks,” said Voinea. “They are sometimes surprised when I tell them I’m deaf and cannot hear. But then we move on and adapt the communication by typing. I think by using my creativity and passion, maybe I will learn how to use even more advanced video game engines in the future.”

Who else wore No. 90 in SoCal sports history? Make a case for:

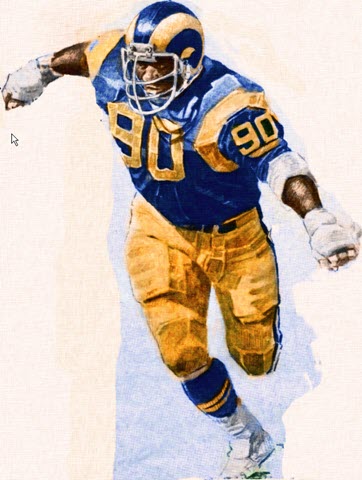

Larry Brooks, Los Angeles Rams defensive tackle (1972 to 1982):

Selected to five Pro Bowls between ’76 and ’80, Brooks started 72 of 74 games in that stretch and piling up 43 sacks, including 14 ½ in ’76. He was first-team All-Pro in ’77 and ’79. He also had 11 sacks in ’74 in 13 games, making second-team All-Pro that year (and again in ’78). He led the Rams defensive linemen in tackles every year from 1973 through 1980, with the exception of 1975 when he injured a knee at mid-season. What was the secret? Teammate Jack Youngblood said Brooks was the best he’s ever seen at the “butt technique” — a “three-point landing with hands on shoulder pads and facemask to facemask. … Larry would just stun the guard” with very low center of gravity that stopped all the momentum of the guard. That allowed Brooks to shed the opponent and was free to make tackles. After Brooks retired, he spent eight seasons as the Rams’ assistant defensive line coach, starting a long career in the coaching profession. It should also be noted he made a cameo as “third substitute teacher” in the ABC sit-com “Welcome Back Kotter” in ’75.

Mike Wise, Los Angeles Raiders defensive end (1986 to 1990):

The Raiders selected the 6-foot-7 Wise in the fourth round of the 1986 NFL Draft out of UC Davis. He played in 50 games with 27 starts and piled up 9 1/2 sacks and four fumble recoveries. An injury-marred career included walking out of camp in contract disputes, unhappy about his diminished role on the team, and distraught over the declining health of his grandfather. Wise also got into a fight with teammate Emanuel King, knocking him down with one punch — King came back with a tire iron and wanted to attack Wise.

The Raiders released Wise to free agency, he went to Cleveland and was cut in training camp by Cleveland. Wise was determined to have committed suicide at his home in Davis in 1992 from a self-inflicted gunshot wound to the head. He was 28.

Bear Alexander, USC football defensive tackle (2023 to 2024):

The 6-foot-3, 315-pounder was “pushing to become the Big Ten star the Trojans need,” according to a fall camp 2024 story in the Los Angeles Times. Alexander’s first year at USC, after transferring from a national title run at Georgia, “had been filled with flashes of ferocious, unblockable brilliance. But those flashes of greatness often faded into prolonged uneven stretches, and Alexander finished with just 1½ sacks and 6½ tackles for loss,” the story read. Months earlier, USC head coach Lincoln Riley had to convince Alexander to not to back to the transfer portal. But three games into the ’24 season, Alexander, with five total tackles, had left again, following a 27-24 home loss against Michigan. Initially he said it would redshirt. Then he left north for rival Oregon. Where those with the name like “Bear” feel it’s more bearable.

Anyone else worth nominating?

Great story. Inspiring!

On Thu, Oct 30, 2025 at 8:42 AM Tom Hoffarth’s The Drill: More Farther Off

LikeLike

What an article, thank you for this!

LikeLike