This is the latest post for an ongoing media project — SoCal Sports History 101: The Prime Numbers from 00 to 99 that Uniformly, Uniquely and Unapologetically Reveal The Narrative of Our Region’s Athletic Heritage. Pick a number and highlight an athlete — person, place or thing — most obviously connected to it by fame and fortune, someone who isn’t so obvious, and then take a deeper dive into the most interesting story tied to it. It’s a combination of star power, achievement, longevity, notoriety, and, above all, what makes that athlete so Southern California. Quirkiness factor sin. And it should open itself to more discussion and debate — which is what sports is best at doing.

The most obvious choices for No. 7:

= Bob Waterfield: UCLA football; Los Angeles Rams

= Lamar Odom: Los Angeles Clippers; Los Angeles Lakers

= Matt Barkley: USC football

= Julio Urias: Los Angeles Dodgers

= Don Rogers: UCLA football

= Steve Yeager: Los Angeles Dodgers

= Mark Carrier, USC football

The not-so-obvious choices for No. 7:

= Todd Marinovich: Mater Dei High football, Capistrano Valley High football

= Mark Harmon: UCLA football

= Jay Schroeder: UCLA football

= Frankie Kelleher: Hollywood Stars baseball

= Dennis Thurman: USC football

The most interesting story for No. 7:

Todd Marinovich, Santa Ana Mater Dei High School and Capistrano Valley High football quarterback (1985 to 1989), USC football quarterback (1988 to 1990), Los Angeles Raiders quarterback (1991 to 1992), Los Angeles Avengers quarterback (2000 to 2001)

Southern California map pinpoints:

Mission Viejo, Santa Ana, Los Angeles (Coliseum, Staples Center), Newport Beach, Irvine, Indio

Proceed with caution if you decide to use Todd Marinovich as sports’ poster boy for the ultimate “cautionary tale.” It’s old news in this case.

The label can still a bit addicting for journalists who think they’ve accurately reported on his creation story, going back to his time as a high school quarterback in Orange County setting California state high school passing records. They then observed his personal and playing career arch reveal extreme highs and lows at USC, the NFL’s Los Angeles Raiders, circling back to Los Angeles for a run with an Arena League team to support a drug habit, and eventually landing on a Palm Springs football field near the age of 50 still trying to find himself.

Tale as old as time, but one that needs a fresh angle every now and then.

In a 2019 piece for the Chicago Tribune by Rick Telander, the “cautionary tale” reference got its latest rewind when dissecting Team Marinovich and the mess it seemed to make in the public eye:

“You’ll recall that Todd was the young man manipulated from birth (actually pre-birth) by his father to be the best, purist, greatest quarterback the world had ever seen. Marv had played football at USC, and he wanted, for reasons buried deep within his own inadequacies, to create a boy who would have the sporting genetics for quarterbacking and be trained incessantly, focused unfailingly and driven like a sled dog toward the apex of the country’s most popular game.”

Telander dragged that trope out because he just read something in Sports Illustrated by Michael Rosenberg, titled “Learning To Be Human Again.” As if Marinovich was emancipated from some reverse metamorphic process.

Rosenberg’s launching point was actually a purposeful revisit of that 1988 Sports Illustrated spread Doug Looney laid out titled “Bred to be a Superstar” that likely started the whole social science shebang on judging the Marinovich Parental Method and its doomed-to-fail, real-world predictions.

Before that piece, California magazine dropped one with the headline “Robo QB: The Making of the Perfect Athlete.” Then came a People magazine profile in 1987.

That was the fragile framework created for Todd Marinovich, no matter where he went from there. The poor kid, readers could easily conclude. Talented, kind-hearted, fun-loving, well mannered. Able bodied.

Call Child Protective Services.

We seem to have the idea that one who is abused and manipulated as a kid is set up to abuse himself later in life and continue a genetic pattern of human frailty. Unless that person figures things out with help, counseling and avoiding some sort of tragic ending.

Maybe the “worst sports father” adjective just won’t go away years later. Even if his father literally went away.

But Todd Marinovich can explain better how it happened with him as a willing participant, trying to navigate the life of a high school kid in full media spotlight, and how it really turned out.

That Todd Marinovich was born on the Fourth of July in 1969 may have added to the storyline that started with him on a All-American pathway.

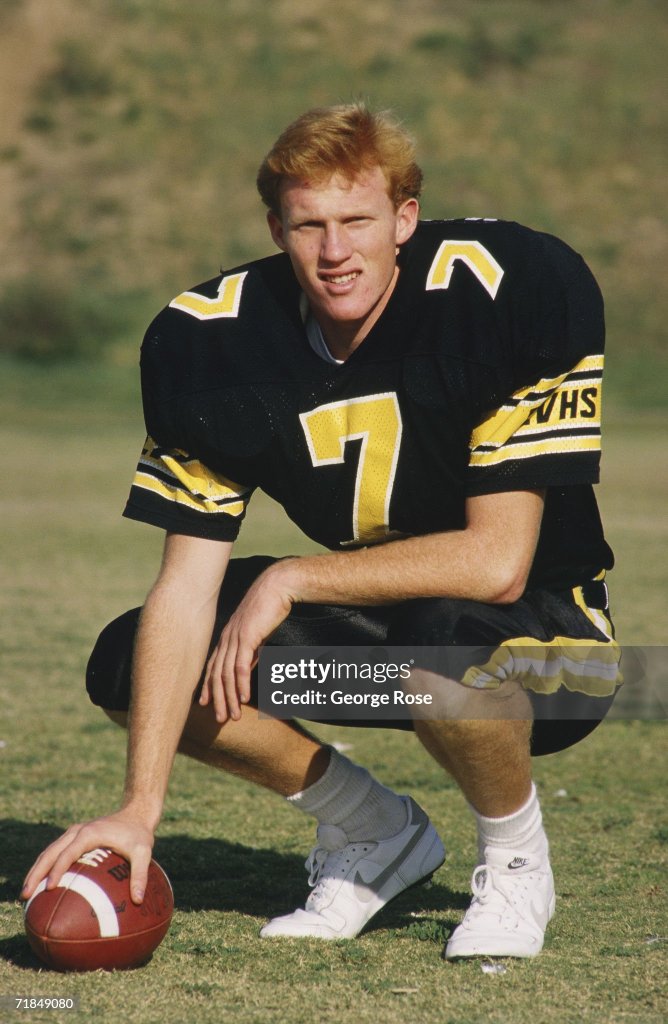

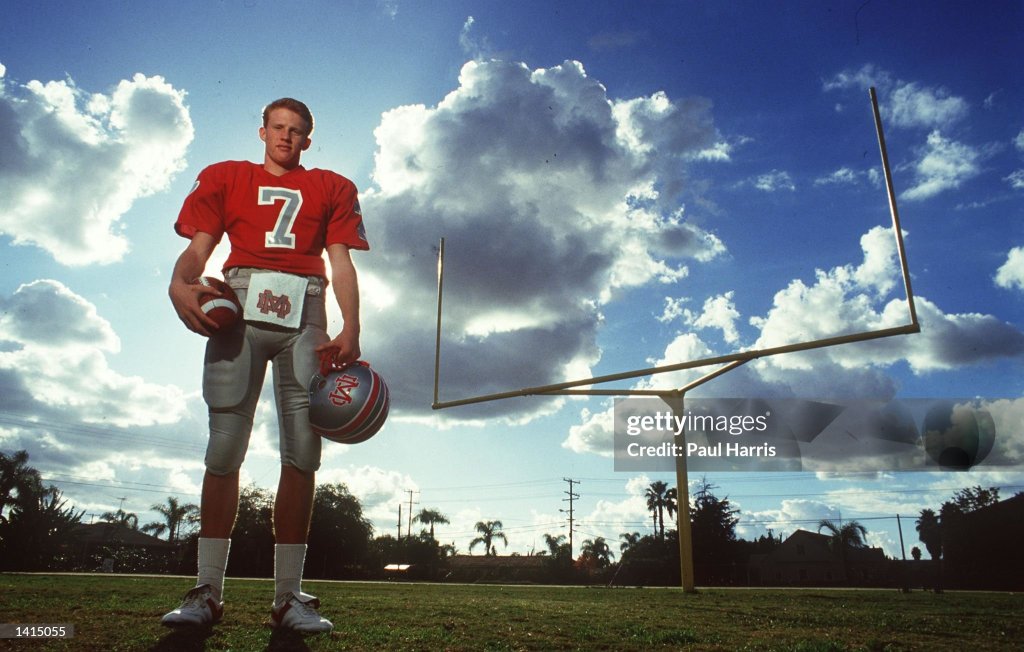

He played a lot of sports, perhaps exceeding most in basketball, but football would be the real test. First were the years at Mater Dei High in Santa Ana, a football factory that had produced Heisman Trophy winners before and after Marinovich’s brief appearance there. That was followed by a surprise transfer to Capistrano Valley in Mission Viejo.

The switch to Capo Valley by his father Marv would be one of things listed on his parents’ separation filing in the courts. Todd has no say in it. He would live with his dad an an in-law quarters at the house of head coach Dick Enright, likely a CIF violation.

While wearing No. 7, Marinovich went up against rival quarterback Bret Johnson in 1987 when ESPN televised its first-ever high school game, between Capo Valley and El Toro.

“I’ll tell you what,” Marv Marinovich told the Los Angeles Times. “There’s more written about Todd back east than there is out here.” Bob Johnson, Bret’s father and the El Toro coach added: “So much more has appeared in the paper about Todd than Bret. They’ve tried to build him up like he’s some kind of perfect kid. The fact the papers write so much about the two is not for me to judge. I think any publicity is good publicity.”

Capo Valley won, 22-21, but it later had to forfeit over some coaching/spying violations by Enright. Keep that in mind when the Marinovich story of his prep days is completely laid out for examination.

But Marinovich, a shy kid just trying to fit in, had already been tempted to try some recreational drugs during high school parties. That spilled over into college recruiting trips.

It was during Marinovich’s time on the Capo Valley basketball team that, during a game against El Toro, fans started chanting “Marajuana-vich” at him as he was shooting free throws. The family had to go into damage control.

Marinovich would throw for 9,914 career yards in high school, a national record at the time. Marinovich passed Ron Cuccia of L.A. Wilson, who held the national record of 8,804 from 1975 to 1977 prior to that. As a senior, Marinovich threw for 2,477 yards.

Life as No. 7 was ending. The magazine stories were already in place as part of his resume. He would never wear that number again in college or professionally. Luckily or not.

He was ready to grow up. Whatever that meant.

The idea that Todd Marinovich allowed his father to put his life to be part of a media/public microscope isn’t far off — but the truth seemed to be more that Todd couldn’t dispute anything for fear of disappointing him.

As much as Todd considered going to Stanford after high school, his USC family history went back to great uncles Bruce and Perry in the ’40s, followed by grandfather Henry Fertig in the ’50s. Uncle Craig Fertig was the Trojans’ starting quarterback in the ’60s. His mother Trudi was Craig’s sister. Todd’s sister Traci Marinovich Grove and cousin Jennifer Fertig also went to USC.

Most evident, father Marv captained the 1962 National Championship team and was a two-way talent as a lineman at USC.

That 1988 SI story only continued the legend of the kid who never ate a Big Mac, Oreo cookie or a Ding Dong based on Marv’s dietary dictatorship. But Todd’s playing ability put him back on the cover of the 1990 college football issue. Still, it focused on his “Growing Pains.”

The story headlined “The Minefield” warned that ” fame and talent may not be enough to see him safely through.”

This was a season after, as a redshirt freshman, he guided the Trojans to a ’91 Rose Bowl win over Michigan in what would be coach Bo Schembechler’s final game.

In two years at USC, he crafted some instant classics — a last-second drive to beat Washington State in 1989 with a two-point conversion, a triumphant 45-42 victory over rival UCLA in 1990.

Eligible to declare for the NFL draft because he put in three full college years, Marinovich seemed to have enough of a toxic relationship with head coach Larry Smith. Especially after a volatile sideline show for the TV audience in a 17-16 loss to Michigan State in the John Hancock Bowl on New Year’s Eve in El Paso, Tex.

In Steve Delsoln’s 2016 book, “Cardinal & Gold: The Oral History of the USC Football Trojans,” Marinovich talks about what happened in a chapter titled “Team Turmoil: 1990.”

Mariovich explained how his time “partying” at USC started on high school recruiting trips “and it continued until my last game there. It never really stopped. Drinking a lot. Smoking a lot of pot. A little bit of cocaine, kind of just beginning with that. Sprinkled in with a little hallucinogenics.”

Marinovich had a sharp 61.2 percent completion percentage, logging 4,649 yards, 28 touchdowns and 21 interceptions for a 133.1 QB rating in both ’89 and ’90.

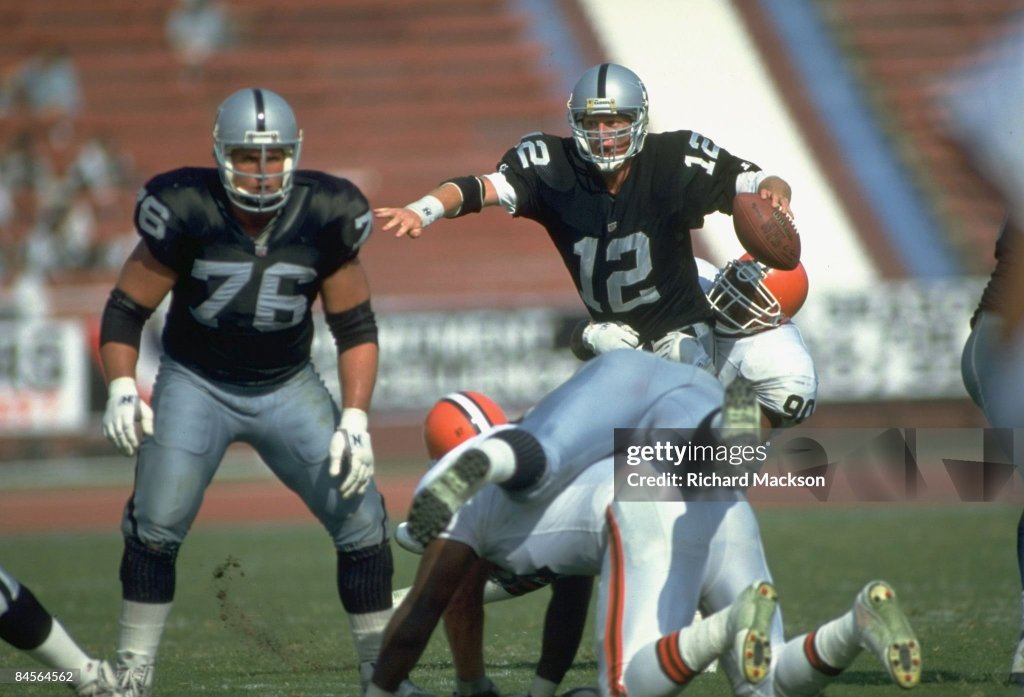

A first-round, 24th-overall choice in the 1991 NFL draft by the Los Angeles Raiders — another team his dad played for and endeared himself to owner Al Davis — was so dazzling that it left Green Bay free to draft quarterback Brett Favre nine spots later.

At that point, Marinovich had already been arrested for cocaine possession a few weeks after his final college game. He had been suspended by Smith in January of ’91 for skipping classes and poor behavior.

That life-as-a-paid-adult experience lasted just two seasons, eight regular-season games, one playoff appearance — eight TDs, nine picks. In a 1991 wild card game, he had four interceptions, no TDs and was sacked twice (12 of 23 passing for 140 yards, a 31.3 QB rating) in a 10-6 loss to Kansas City with a Raiders roster that included Marcus Allen, Tim Brown and Willie Gault as his offensive weapons.

Marinovich watched the Raiders lose a divisional playoff game in Buffalo while he was in a jail cell, during the 1993 suspension by the NFL for his drug use.

Marinovich went north to the Canadian Football League for stops and starts — drugs were easier to come by.

The Los Angeles Avengers of the Arena Football League took him in for two seasons — he was on the AFL’s All-Rookie team as a bit of a lark in 2000. His two year totals: 249 of 472 passing, 3,214 yards, 62 TDs and 21 interceptions.

Another departure, along long period of self reflection. Another embarrassing arrest — a rape charge in Marina del Rey.

What was left to tell about Todd Marinivoch at this point? Were there lessons learned? Things that future dad-son-coach-player relationships could look back on?

Eventually, Marinovich had to get into a place where he stopped trusting others to tell his life tale.

Esquire magazine’s Mike Sager did a long piece on Marinovich in 2010 titled “The Man Who Never Was.”

In December of 2011, as ESPN Films came out with a documentary called “The Marinovich Project,” Marinovich told reporters that Sager story was “fiction … I was disappointed by it, really felt let down. I laid it all out there for Mike, but it didn’t ring true for me.”

Such it is when others want to write the “the Marinovich profile” and have their own interpretations.

That ’11 ESPN documentary had a screening in Hollywood. Marinovich retreated to the men’s room before the house lights came up. His eyes were swollen from crying.

“I never thought the media evaluated the situation (of Todd’s upbringing) correctly, but that’s just my opinion,” Marv Marinovich said. “This is really how it happened.”

The next day on the phone, Todd explained to me: “That was an overload. There was a lot of uncomfortable moments. After I had a chance to soak it in, I was very impressed. A lot of that on the screen, it didn’t feel like me. It was a trip. I knew the story, but I was tired of hearing the one that was so blown out of proportion. The real human being was lost in the shuffle.

“I don’t know if there are lessons to be learned. My dad and I have a healthy relationship. It may not have always been that way, but I know it is today. It’s a positive story.”

Marinovich tossed up a sobering moment in the fall of 2017. Faith, hope and redemption became buzzwords resurrected for the event.

Pulling on a No. 12 red, white and blue jersey for the SoCal Coyotes football team –a Palm Springs-based non-profit entity in something called Development Football International that helps nurture young talent — Marinovich went back in time to meet himself.

In a game officially recorded as a 73-0 victory by the Coyotes over the California Sharks, Marinovich completed 19 of 28 passes for 262 yards and seven touchdowns, with two interceptions. The game at Shadow Hills High School Stadium, just off Interstate 10 in Indio, drew about 250 family and friends. Among the curious was Raiders owner Mark Davis.

The most compelling number was 48 — Marinovich’s age. The 6-foot-4, 220-pound bald left-hander with a scraggly gray-red beard was addicted to the idea presented to him months earlier of getting in shape to play in an actual game.

Because that’s Marinovich, knowing his addictive nature.

In August of 2016, Marinovich was in a drug- and alcohol-induced blackout when police found him nude in a stranger’s backyard in Irvine, holding a brown bag with methamphetamine, syringes and his wallet. His estranged wife, Alix, knew something was wrong when he came to pick up their two children, his beard shaved his his face “looked like a skeleton,” she said.

He pleaded guilty to five misdemeanors and was sentenced to rehab and probation and was told if he completed six months of outpatient rehab, he wouldn’t have to serve any more jail time.

This time with the SoCal Coyotes were part of his penance. So was teaming with the Riverside District Attorney’s Office to speak to high school students and those doing time in juvenile hall to warn them about the life that he endured.

“If you were to look up ‘rude awakening,’ that was my experience with the Irvine Police Department,” Marinovich said in April of 2017, months before his comeback game. “It was the most humiliating thing. But thank God for it. I feel so grateful I was arrested, because who knows what would have transpired.”

For Marinovich, this tribal desert proving ground was in a place similar to what a D-League is for the NBA. The Myth of Marinovich was addressed again.

He said he was as pleased with how that game turned out as he was with what didn’t happen.

“I’m just blessed with standing on the planet,” he told the Desert Sun of Palm Springs. “And then playing football? It’s just … I’m speechless.”

It had been 17 years since he last played in a football game. But in July of ’17, Marinovich joined the Coyotes as a quarterbacks coach. It was part of his latest make-good-on-life rehabilitation program treatment, giving him something productive and meaningful. The idea was kicked around that maybe, since it seemed he still could throw the ball around, maybe he was in good enough shape to play.

So he thought about it, and accepted the challenge. Another a step toward helping him feel normal again. Whatever normal is.

But afterward, his left throwing shoulder continued to ache, as he did during the months of his working out. Team physicians told him to back off. That meant Marinovich seemed to be finally finished.

As a football player, at least.

The rest is to be determined.

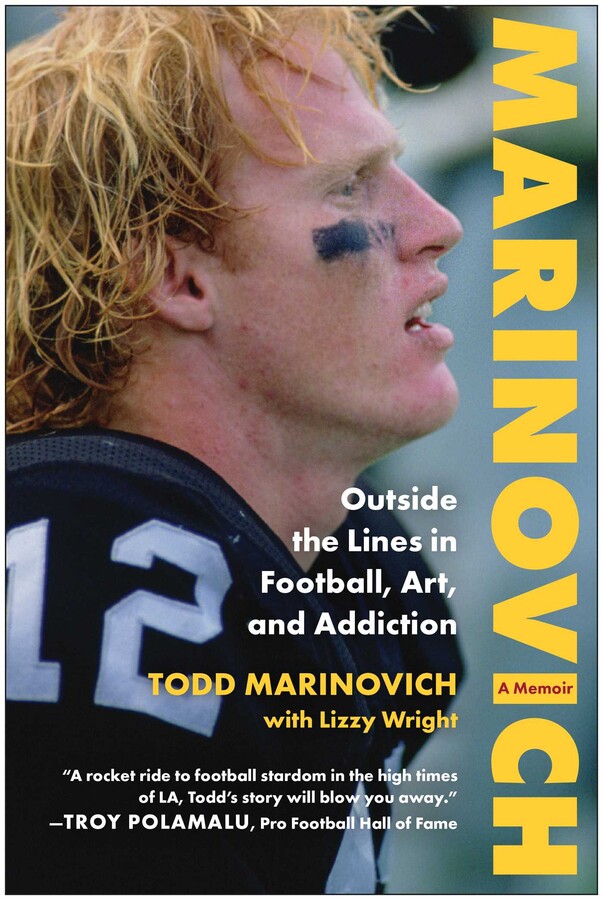

There are all sorts of dots that get connected and narratives regurgitated in the Marinovich mythology, including to the point when, in a 2025 autobiography, he bared more of his soul with the help of writer Lizzy Wright in autobiography titled “Marinovich: Outside the Lines in Football, Art and Addiction.”

The book, according the publisher, was needed because, “for years, the national media has been left unchecked for its careless, incomplete, and often inaccurate portrayal of Todd Marinovich’s meteoric rise to fame, cataclysmic collapse, and unsteady path to self-realization.”

That path includes drug addiction, embarrassing relapse and arrests, anxiety attacks, more erratic behavior, meeting a woman in a rehab center that he would marry and have two kids with, then taking up therapeutic artistic expression, relying heavily on his own life experiences as material to process.

The book, according to Orange County-based writer Mark Whicker, a long-time observer and recorder of the Marinovich journey, “is full of tender regrets and piercing horrors. It is his attempt to straighten out the wrinkles of a story that most people think they know, because the assumptions are so neat. …. Marinovich reminds us that we don’t live in a subject-verb-predicate world. In that way, this book is a public service. He also lets us in on a secret. No matter how bad the ordeal seemed from the outside, double it.”

The book covers his USC days, when he admits to have a tequila hangover from a trip to Juarez, Mexico when he wasn’t sure he was back in the U.S. in time for the game until teammates woke him up. Trojan teammates in the book also talk about how they helped Marinovich pass drug tests by cheating and by reminding him to constantly “deny, deny, deny.”

The book also reveals how, with the Avengers, he realized the danger of wearing white football pants while trying to detox from heroin. He soiled himself three times during a game in Houston as he was throwing 10 touchdown passes.

The book also came out five years after his father Marv died from Alzheimer’s disease. He had another son, Mikhal, born in 1988 when Todd was entering USC. Mikhal, a 6-foot-5, 253-pound defensive end, played four years at Syracuse, out of JSerra Catholic High School in San Clemente as well as Milford Academy. In a 2011 Syracuse game at USC, served as game captain, collected three tackles and made his first career fumble recover.

Mikhail Marinovich’s story never got told as much as Todd’s, who, by some stroke of luck, continues to live on.

In a Q&A with the Los Angeles Times about his book, Marinovich was asked about that 2017 comeback with the minor-league football team in Palm Springs. The experience led to him using drugs. Again.

Marinovich replied:

“At the time, up to that point, I was in maybe the best head space I’d been in. It was about being of service helping people.

“But it was after the training camp, being out in the desert in Palm Springs in the summer, practicing two-a-days at 47, and I was the only quarterback for half the training camp. So my shoulder is just hanging. … It just clicks when I start taking painkillers. It was like someone lit the pilot light. This thing is going to go. We don’t know when, but he’s on that road to addiction, full blown, again. And that’s a stumbling block for a lot of people.

“At the time, I’m thinking, ‘I need it.’ I can’t go to practice without it. All of these things are excuses. I need someone close to me to point out, like ‘Dude, this is where you’re going.’ I fool myself. Like, I gotta practice. And I gotta take this to practice, and when I take that, all bets are off. And it’s a matter of time.

“It’s a great lesson. But what I understand is that a lot of people that aren’t here had the same ideas. Like we’re just gonna do this because of this, and this, and then this. I got the lesson, and thank God, I’m really fortunate that I lived through it. Because a lot of people don’t. And I’ve gotten some chances, and I’m really grateful for that. ‘Cause I like being here.”

While once living in Irvine with his mother Trudi, Todd has moved to the big island of Hawaii to see solace.

“I’ve stopped fighting everybody and everything, I was one of the most defiant people on the planet,” he said. “On self-reflection, where did that actually get me? It didn’t help me out in any positive way.”

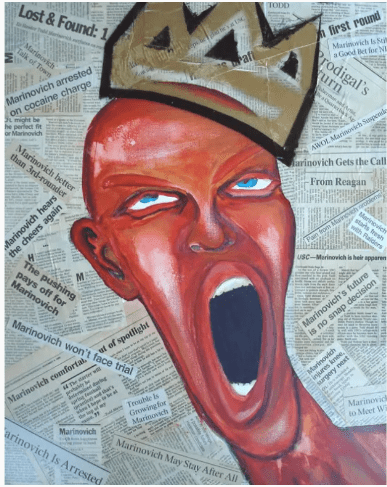

Marinovich came away as an art major at USC. It has given him a platform to express himself for years, before his memoir emerged.

The self-reflective Expressionist and Impressionist oil paintings of his life includes one called “The Crown.” Marinovich looks like Edvard Much’s “The Scream,” with headlines of his life dancing in the background. He said he found an old trunk in his grandmother’s garage.

“I couldn’t see myself saving all these things and making a scrapbook so I used them in my art,” he said in a 2011 interview. Headlines such as “AWOL Marinovich Suspended,” and “Trouble Is Growing for Marinovich.”

“Art takes me away,” he says. “I can escape into a place that … it’s hard to describe, but time is non-existent in this place, and there’s a flow to it. It’s kind of similar to athletics, there’s a flow to athletics. But with art, there are no rules, and in football, there are.”

Another self-portrait called “Defeat III” shows him as a dark shadow sitting on his helmet.

“It’s always been one of my favorites,” the then-42-year-old told me in 2011. “That’s probably the one that I’ve sold the most. I’ve done six versions of it. The bright colors take on the emotions of it. I can’t do one like I do the next. All I was trying to do was create something that I felt was like defeat. As much fun and exciting as it was to get over a victory, it didn’t affect me in the same way as a defeat. So much more is remembered and learned in a defeat.

“I go through happy and depressed moments, and here, I can recreate every emotion that I feel as a human. Without art to express it, I’d be lost. It’s been fabulous for all my aftercare. It’s an unbelievable liberating feeling.”

At a book event in Huntington Beach, attended by some of his former Raiders teammates, Marinovich, at age 56, said he was still “a work in progress.”

In his book, he writes: “My most fundamental flaw was both a tremendous blessing and a horrible curse, but it was my reality. Without the zeal accompanying obsession, who knows if I would’ve succeeded in football? Someone else could have been the first college sophomore in history to declare for the NFL Draft. Yet, on the flip side, there wouldn’t have been a soul-crushing dozen arrests, five incarcerations, and over seven trips to rehab.”

Who else wore No. 7 in SoCal sports history? Make a case for:

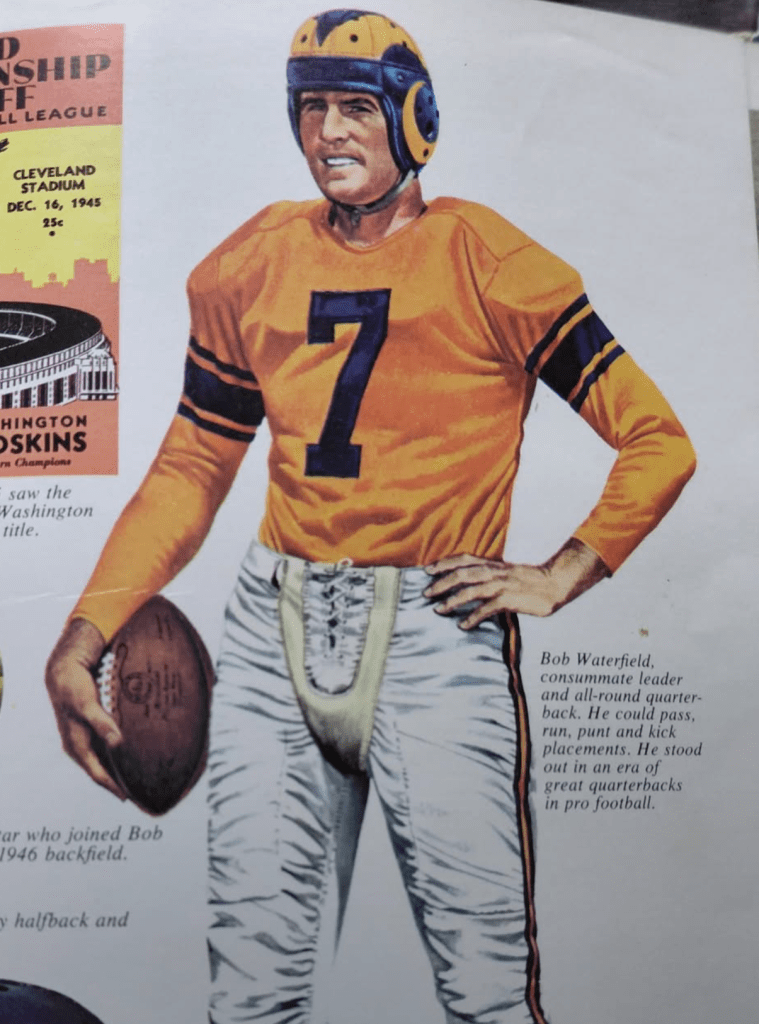

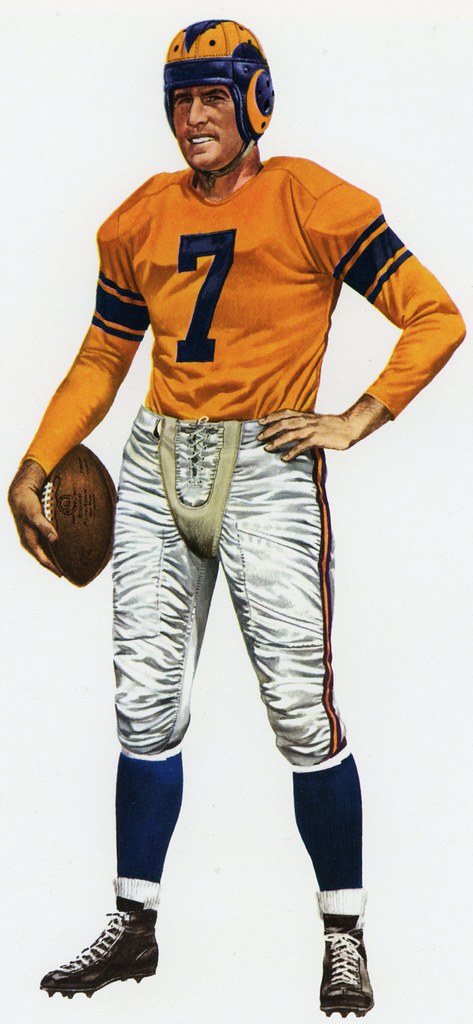

Bob Waterfield, UCLA football quarterback/defensive back/punter/kicker (1941, ’42 and 1944) and Los Angeles Rams quarterback/defensive back/punter/kicker (1946 to 1952):

Seven was the lucky number Waterfield wore while taking UCLA to its first Rose Bowl during his World War II-interrupted college schooling period. Seven was also the number he had already established for himself as the Rams star quarterback when the franchise abandoned Cleveland and migrated to Los Angeles to become the NFL’s shiny new object of affection, going to three straight championship games as the city’s representatives.

Seven became the first number the Rams’ franchise retired — the same year, 1952, when Waterfield himself retired at age 32 because he had better things to do.

A New York native who moved with his family to the San Fernando Valley when he was nine and starred in all athletics that Van Nuys High could offer, Waterfield gravitated to the UCLA campus in 1941. A year later he nearly single-handedly carried the Bruins to the Pacific Coast Conference championship and, it should be noted, their first win on the gridiron against rival USC. The two schools started playing each other in 1929, and in their eight meetings prior to ’42, the Trojans won five, with three ties. Waterfield took No. 13 UCLA to a 17-14 win over USC before 90,000 at the Coliseum on Dec. 12, 1942 to finish 6-1 in the PCC and capture the Victory Bell, at a time when students were busy selling war bonds. The Bruins wouldn’t beat the Trojans again until seven meetings later in 1946.

Appearing in 557 of the 600 minutes that UCLA played in its 10-game schedule, Waterfield also averaged 40 yards on 60 punts. He led the conference that season with 1,033 yards passing and 12 touchdowns.

Two months after UCLA lost the 1943 Rose Bowl by a 9-0 score to No. 2 Georgia — one of Waterfield’s punts was blocked out of the end zone for a safety in the fourth quarter for the game’s first points — he eloped to Las Vegas with actress Jane Russell, his Van Nuys high school sweetheart who was on an upward trajectory to becoming one of the first pin-up girls for soldiers and starting her movie career.

From there, Waterfield was off to serve in the U.S. Army, sent to Fort Benning during World War II. Honorably discharged in June of 1944 with a knee injury he suffered playing for the 176th Infantry football team, Waterfield circled back to UCLA to finish his playing career and was second-team All-PCC.

Perhaps what clinched his value was his performance in the Jan. 1, 1945 East-West Shrine Game in San Francisco, catching the game-winning pass for the West squad in the closing minutes. Still, the Cleveland Rams were hardly confident in Watefield’s abilities when they waited until the fifth round (still, the 42nd pick overall) to secure his rights in the 1944 Draft — which, in this time of sensitivity, was called the “Preferred Negotiations List.”

Still devoted to wearing No. 7, the rookie lead the Rams to the NFL championship with a 9-1 record, leading the league with 1,627 yards of total offense and 14 touchdown passes. As a defensive back, he also had six interceptions. Unanimously, Waterfield was named NFL MVP, which was before he orchestrated a 15-14 win over Sammy Baugh’s Washington Redskins in the ’45 title game in below-zero weather in Cleveland. Waterfield not only threw TD passes of 37 and 44 yards for the only two scores, he also supplied booming punts that kept the Redskins pinned deep in their own territory the entire game.

Just before that game, Rams owner Dan Reeves announced that the team had given Waterfield to a three-year contract paying him at the unheard-of astounding rate of $20,000 per year. That made him the highest-paid player in pro football. And he was about to go home to flaunt it.

The Rams moved out of Cleveland and found Los Angeles for the 1946 season, and Waterfield continued his All-Pro status by leading the league with 17 touchdowns and second with 1,747 passing yards to be an All-Pro quarterback again.

Soon, he found himself as the co-star of the team.

After the Rams lost the 1949 NFL title game to Philadelphia, they drafted Norm Van Brocklin as a quarterback. It meant that Waterfield and Van Brocklin would share the position — each starting six games in 1950 on a team that lost to the new Cleveland Browns in the NFL title game. On the first play of scrimmage in that game, Waterfield threw an 82-yard touchdown pass to Glenn Davis.

Before the 1951 season, Waterfield followed his wife into landing himself movie roles. His first part — a former football star who had gone missing for nine years on a military flight, which sent Johnny “Jungle Jim” Weissmueller on a mission to rescue him in “Jungle Manhunt.“

Because of injury, Waterfield missed the Rams’ 1951 season opener — Van Brocklin stepped in and threw for an NFL record 554 yards, which still stands. But Waterfield started 10 of the Rams’ last 11 games and lead the league with a 81.8 passer rating. In the Rams’ 24-17 win at the Coliseum over Cleveland was the franchise’s only NFL title representing L.A. until Super Bowl LVI in 2022, Waterfield’s two first-half interceptions accounted for two of the Rams’ three turnovers. But his 17-yard field goal in the fourth quarter gave the Rams a three-point lead.

It was the Rams’ first win over Cleveland in a title game in four tries, and the Associated Press noted in its story that “the payoff was a personal triumph for Rams number one quarterback and captain Bob Waterfield, who led the club to its only other NFL title in 1945.”

The ’51 team is considered one of the deepest in NFL history as well as setting a template as to how pro athletes could navigate the Hollywood scene.

In ’52, it was back to splitting games with Van Brocklin, and that led to Waterfield announcing he would retire at the end of the ’52 season. His NFL resume would have four league records — 315 extra points, including 54 in the ’50 season, and 60 career field goals, including five in a game.

Now, it was back to movies. He teamed with wife Russell to create the Russ-Field Production company. Russell was just coming off her pinnacle role in “Gentlemen Prefer Blondes (1953)” as Dorothy Shaw, with Marilyn Monroe. In 1956, Russ-Field put out “Run for the Sun” in 1956 (with Richard Widmark and Jane Greer, the later who would become Waterfield’s second wife) and a western-comedy “The King and Four Queens” (with Clark Gable). Later, Russell starred in their production of “The Fuzzy Pink Nightgown” in 1957.

Waterfield didn’t wander far from the football field even as Hollywood called.

He coached the Rams’ kicking game (1954 and ’55), the also developed the quarterback position (1958). But when head coach Sid Gillman resigned, Waterfield, then 40, signed a five-year deal to take over. A Hollywood flop — the team went 4-7-1 and 4-10 in his first two seasons and was spiraling at 1-7 when he quit in the middle of the ’62 season.

His inclusion in the Pro Football Hall of Fame in 1965 made him part of the institution’s third induction class. A year after Waterfield died at age 62 in 1983, he was made a charter member of the UCLA Athletic Hall of Fame.

The school called him “one of the most charismatic quarterbacks in college and professional football history.”

Waterfield’s IMdB.com data base shows three listings as an actor and six as a producer. No Hollywood Walk of Fame stars. It also lists his nickname as “Buckets.”

So kick that around.

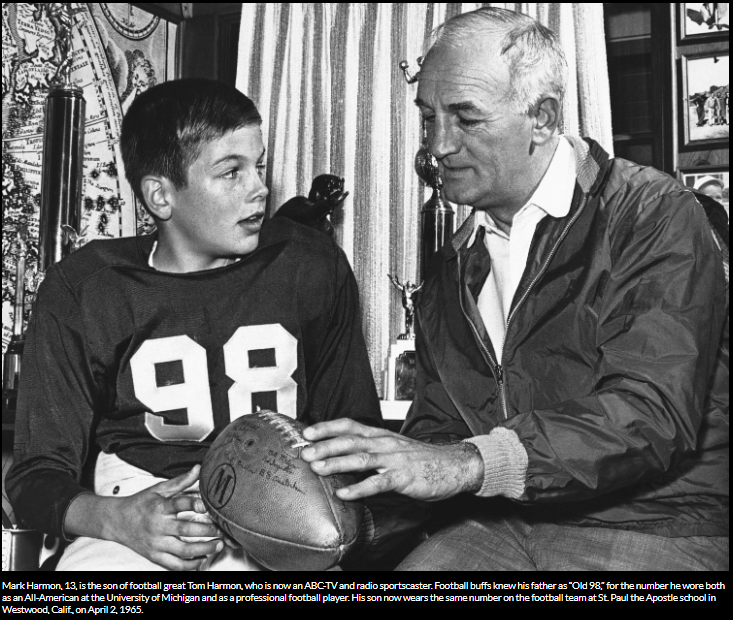

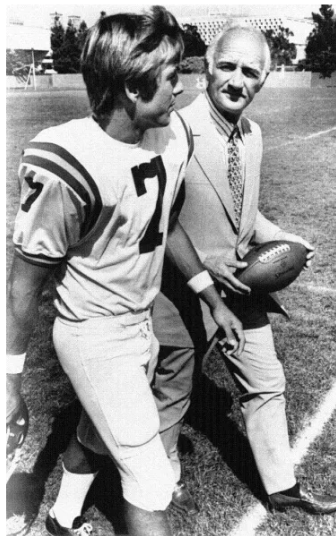

Mark Harmon, UCLA football quarterback (1972 to ’73):

As the son of Michigan’s “Ol 98” who won the Heisman Trophy trophy in 1940, a year before Bob Waterfield started at UCLA, Mark Harmon may have felt like a marked man when it came to athletics.

Eventually, People magazine’s “Sexiest Man Alive” was marked on another career path.

Mark Harmon actually suited up as No. 98 while playing at St. Paul the Apostle Catholic School in Westwood as a 13-year-old in the mid-1960s. At the private Harvard School (now Harvard-Westlake) in Studio City, he played football, baseball and rugby. He broke his elbow as a junior and didn’t play varsity football as a senior. He’d only played quarterback for four games at Harvard, and mostly was a running back on offense and a safety on defense. He was a much better baseball player – a catcher. But with a mind set perhaps in the medical field, Harmon had a plan laid out.

“I wanted to go to school for a year and half, get an AA degree by spring of my sophomore year and then go to the (four-year) college where I wanted to be,” he explained in a 2010 interview as he was about to be inducted into the first Pierce College Athletic Hall of Fame. “Santa Monica College would have been closer – I still lived at home with my parents (in Brentwood), but coming from where I did and the kind of experience I had in the classroom and on the field, Pierce was a gold mine for me. I was a student first. They had great teachers, some of them who were on sabbatical from local universities. It had a great campus and it was a great place to be.”

As a sophomore at Pierce, he led the team to a 7-2 record and was a NJCAA All-American.

Oklahoma came hard trying to recruit Harmon – he remembers offensive coordinator Barry Switzer telling him they’d win a national title with or without him. His father’s alma mater, Michigan, also wanted him. But his heart told him to go to UCLA, with assistant coaches Lynn Stiles and Terry Donahue making the pitch for the Bruins. Med school was still the plan. So was football, as head coach Pepper Rogers, had offensive coordinator Homer Smith running their own version of the vaunted Wishbone attack.

Harmon wore No. 7 at UCLA — the same as Waterfield, who had a somewhat parallel college career as Harmon’s father, Tom. Coming off an eighth-place 2-7-1 record in 1970, the ’71 Bruins didn’t know what was in store.

(Photo by George Long /Sports Illustrated via Getty Images)

Harmon gave them a taste in his first game. He orchestrated a 20-17 upset over the two-time defending champion Nebraska, snapping the Cornhuskers’ 32-game win streak. The Bruins were 18-point underdogs against the top-ranked team in the country.

In the 1972 and ’73 seasons in Westwood, Harmon ran for 14 touchdowns and threw for nine scores as a starter in Pac-8 competition. The Bruins combined for a 17-5 record those two seasons.

Harmon often traded snaps with John Sciarra as they incorporated running backs Kermit Johnson and James McAlister into the running attack. Harmon started all 11 games his junior year but had to share playing time with his Sciarra, his roommate. According to a 1987 GQ magazine article, the competition between the two became so fierce, Harmon moved out.

Harmon was smart enough to know he could do more than just rely on sports to take him into the spotlight. He again considered medicine. Or law. A Communications with a 3.45 GPA and graduating cum laude, he was an National Football Foundation Scholar-Athlete Award recipient in 1973.

Harmon said that during his senior year at UCLA, he had the opportunity to be on set for a week and observe an actor, producer, writer and director.

“There is something about walking onto a set. Maybe it’s the team part of that I totally understood, and my focus really was, ‘Okay, how do I do this? How do I get on set?” Harmon said.

Harmon said he met an actor and producer who gave speeches at the boys club and he remembered seeing that person’s name in the credits of “Dragnet” and “Emergency!” He thought he should try calling him and see what happened.

“I looked in the phone book, and it said ‘Mark VII productions, Jack Webb’s Universal Studios,’ and I called him and he got on the phone. He remembered meeting me, and he was a good man. He invited me to come in and talk to him, which I did the next day. That was an opportunity he didn’t have to provide,” Harmon said.

Again, “Mark” and “Seven.” It’s all adding up.

Acting seemed to be in the Harmon DNA. His mother, Elise Knox, was herself an actress and model, and his father Tom had become TV famous again as a local and national sportscaster. His older sisters, Kris (married to Ricky Nelson and became part of the “Ozzie and Harriett” TV show cast) and Kelly (married to John DeLorian), were also in the business.

Mark worked in advertising, as a athletic shoe company rep and as a carpenter between acting gigs before he got noticed on a Coors beer commercial. Then came NBC’s “St. Elsewhere,” CBS’s “Chicago Hope,” NBC’s “The West Wing” (earning an Emmy nomination) and eventually an extended run on CBS’s “NCIS” as agent Gibbs. Married to actress Pam Dawber, Harmon became the “NCIS” executive producer in 2011.

In 1988, Harmon was part owner of the San Bernardino Spirit minor-league team, where Ken Griffy Jr., happened to be playing. Harmon used the team and their home field for the opening and closing scenes of the film in which he was starring, “Stealing Home.”

In 2011, Harmon got to revisit the Los Angeles Coliseum in the ninth season of “NCIS” in an episode called “Devil’s Triangle,” as his former UCLA football home was decorated as the home field of Monroe University playing the Armed Forces All Stars, and agent Gibbs was scrambling on the roof of the press box to thwart a terrorist attack.

In 2012, he got a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame. With a little TV screen on it.

“I look at the show as a team,” Harmon said prior to receiving the 2019 National Football Foundation Gold Medal award for his career’s work. “I’ve always been a team guy. I’m not in [acting] for the personal part of this, and I wasn’t as an athlete either. It’s about the work and we all work together.”

When People magazine bestowed him with its annual “Sexiest Man Alive” honor in 1986, Harmon was quoted about his athletic career: “I was pretty average as an athlete, I just tried harder than most.”

Harmon’s IMbD.com data base shows 76 acting roles to his credit, plus five producing and two directing credits. It also lists his nicknames as “Silver Fox,” “Papa Smurf,” “Gibbs,” “Charmin Harmon” and “Quarterback.”

“Wouldn’t it be nice if life really read like a bio?” Harmon once said. “I get it that people would look at that and think this is the path you’re going to take (based on his parents’ fame), but I don’t remember it like that at all.”

Matt Barkley, USC football quarterback (2009 to 2012):

Sixth in the 2011 Heisman voting after his junior year, Barkley had a 148.7 career quarterback rating that reflected his 12,327 yards passing, 116 touchdowns and 48 interceptions in four full seasons. But did he really fulfill his promise? Born in Newport Beach and a star at Mater Dei High (wearing No. 5), Barkley passed for 6,994 yards and 57 touchdowns in his first three prep seasons, winning the 2007 football Gatorade National Player of the Year as well as the Gatorade National Male Athlete of the Year, the first non-senior to win both awards. He finished his Mater Dei High School career as the all-time passing yardage leader in Orange County, surpassing the mark of Todd Marinovich in 1987. Barkley became the first true freshman quarterback to ever start an opener for the Trojans. But by the time he became a Heisman favorite as a senior, with USC as a pre-season No. 1 team, the Trojans lost five games taht season, including one to UCLA, and Barkley was knocked out of the game against the Bruins with a shoulder separation. He was picked in the fourth round of the NFL draft by Philadelphia.

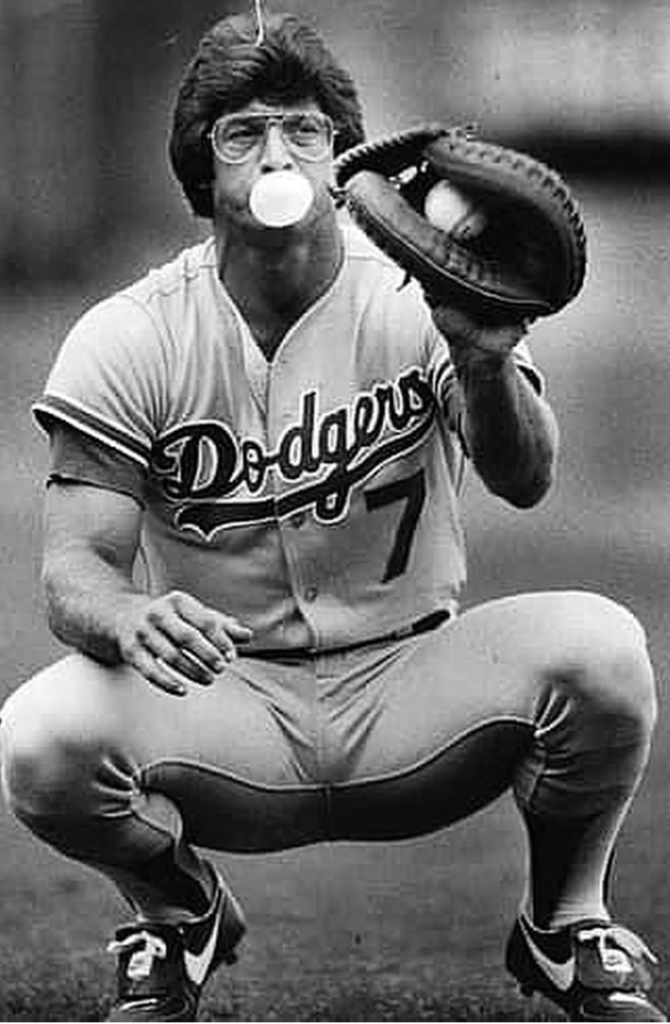

Steve Yeager, Los Angeles Dodgers catcher (1973 to 1985):

After wearing No. 41 as a rookie in ’72, Yeager caught on as the Dodgers’ regular catcher by 1974 and led NL catchers in baserunners caught stealing in both 1978 (46.7 percent) and 1982 (43.1 percent). Yeager has one-third possession of the 1981 World Series MVP Award, sharing it with Pedro Guerrero and Ron Cey, because one of his two homers in the series was a crucial one off the Yankees’ Ron Guidry in Game 5 that resulted in a 2-1 Dodgers win. With that exposure, he posed (somewhat) nude for Playgirl magazine in 1982. All that after he was once hit in the throat by a broken bat while kneeling in the on-deck circle in 1976, getting credit for helping develop a throat guard, a shoe-horn looking device that dangled from the bottom of the catcher’s mask. Yeager also coached the Dodgers catchers from 2012 to ’18.

Robby Gordon, NASCAR Cup Series driver (1991 to 2012):

Born in Cerritos, Gordon can be included in the lists of the Top 10 NASCAR drivers from Southern California as well as the sport’s 75 greatest drivers. He won three times in the Sprint Cup Series and wound up operating his own team. He is also the only driver in the world who has recorded race wins in NASCAR, IndyCar, IMSA, stadium and off-road racing (including the legendary Baja 1000), as well as several stage wins in the Dakar Rally.

Robbie Keane, Los Angeles Galaxy forward (2011 to 2016):

The best forward on the league’s most dominant team, playing with David Beckham and Landon Donovan, the Irishman a nod on the naming of the 25 greatest players in MLS history as of 2020. With 73 goals and 43 assists over 108 regular-season appearances, Keene also netted nine goals and six assists across 18 playoff appearances, helping the Galaxy to MLS Cup wins in 2011, 2012 and 2014. He was the league and MLS Cup MVP in 2014 and is a four time best XI selection.

Son Heung-Min, LAFC forward (2025 to present):

After a decade with Tottenham Hotspur of the English Premier League, scoring 173 goals in 454 matches (fifth-highest goal scorer in Tottenham history), the 33-year-old from South Korea joined LAFC at a record transfer fee of $26.5 million. He scored 51 goals in 134 national team appearances for South Korea, helping his nation to the Asian Games title in 2018 and the Round of 16 at the 2022 World Cup. He made his debut in a 2-2 tie against Chicago, drawing a penalty kick that knotted the game. Sports Illustrated called Son’s acquisition among the most important in MLS history.

Don Rogers, UCLA football defensive back (1981 to 1983):

Inducted into the UCLA Athletic Hall of Fame 20 years after his final game, Rogers lead the Bruins in tackles three straight seasons, ranked second all-time with 405 tackles. As a junior, he was co-Player of the Game for the 1983 Rose Bowl with 16 tackles and two interceptions as the No. 5 Bruins outlasted Michigan. The next year, he intercepted two more passes, the first just 43 seconds into the game, to set the tone as the Bruins upset No. 4 Illinois. The 18th pick in the first round by Cleveland, he played two NFL seasons before his death in 1986 as a result of a cocaine-induced heart attack.

Lamar Odom, Los Angeles Clippers forward (1999-2000 to 2002-03, 2012-13); Los Angeles Lakers forward (2004-05 to 2010-11):

The 6-foot-10 left-handed shooting forward played one season at Rhode Island before the Clippers took him No. 4 overall in the 1999 Draft. By the time he made it to the Lakers, coach Phil Jackson liked him better off the bench, and Odom won the NBA Sixth Man of the Year honor for helping them win two titles. His marriage to reality star Khloe Kardashian, his inclusion in a trade to New Orleans for Chris Paul in 2012 that was rejected by the NBA, and his hospitalization in 2015 for a drug overdose will also follow him on his permanent record.

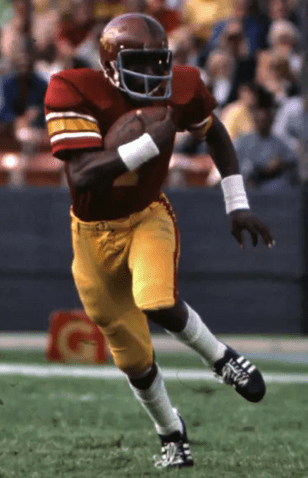

Mark Carrier, USC football safety (1987 to 1989):

USC’s first Thorpe Award winner in 1989 as the nation’s top defensive back, Carrier was a two-time All-American in his three seasons and the Trojans went 27-8-1 in his career. The Long Beach Poly star led USC in interceptions in 1989 with seven, which led the Pac-10 in interceptions per game. He is tied for sixth on USC’s career interception list (13). He was inducted into the USC Athletic Hall of Fame in 2007 and made the Pac-12 All-Century Team in 2015. He played 10 years in the NFL, making the Pro Bowl three times.

Dennis Thurman, USC football flanker/safety (1974 to 1977):

Voted into the College Football Hall of Fame in 2025, Thurman came out of Santa Monica High as a star quarterback and defensive back on three CIF Division I teams that went a combined 39-1-1, and as an athlete he was recruited for college basketball and could have signed a pro baseball contract. At USC, head coach John McKay moved him to flanker when Sheldon Diggs was hurt and, as part of the 1974 national title team, Thurman’s freshman highlight was intercepting a pitch out and returning it 84 yards in a 34-9 win over UCLA. He stayed as flanker as a sophomore in ’75 but was moved back to free safety as a junior and pulled in eight interceptions, including a pick in seven straight games. He also led the team with 17 punt returns. As a senior, he was named Defensive Player of the Year and won the second of his All-American honors and had a 47-yard TD return from a Theotis Brown fumble for a touchdown against UCLA. In addition to the first Rose Bowl win, he was also on teams that won a second Rose Bowl, plus the Liberty and Bluebonnet bowls. After 12 years in the NFL, he returned to coach the secondary at USC from 1993 to 2000.

Have you heard this story?

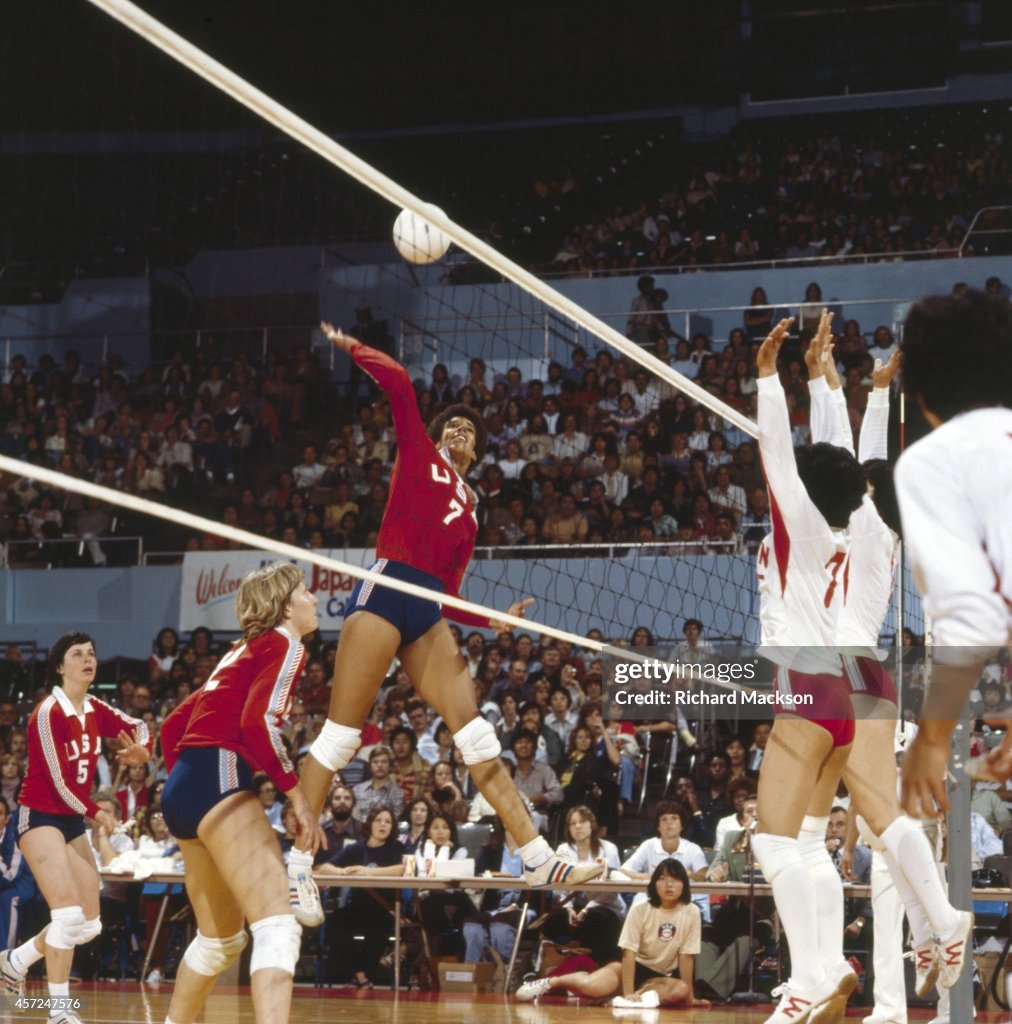

Flo Hyman, Morningside High and El Camino College volleyball outside hitter (1969 to 1974):

The bio at Olympics.com comes right out and says: “Flo Hyman is usually considered the greatest ever American women’s volleyball player.” At 6-foot-5 and with a spike that registered at more than 100 mph, Flora Jean Hyman stood tall wearing No. 7 for the U.S. Olympic women’s volleyball team that won silver at the 1984 Los Angeles Summer Olympics, performing before friends and family not far from where she grew up in Inglewood at Morningside High. She had already started playing professionally at age 16 in 1970. A year after going to El Camino College in Torrance, she accepted the first female scholarship at the University of Houston and led the team to national prominence, winning the Broderick Award as the nation’s top female collegiate volleyball player in 1977 a year after she was named AIAW National Player of the Year. Having been on the 1980 team that boycotted the Games in Moscow, Hyman was 29 — the tallest and oldest — of all the players on the ’84 team that make to the gold-medal final but lost to China at the Long Beach Sports Arena. Playing professionally in Japan afterward, she collapsed and died during a match in January, 1986. She was 31. An autopsy in Culver City by her family ruled out a heart attack and identified Marfan Syndrome causing damage to her heart. She was bured in Inglewood Park Cemetery. Sports Illustrated had her on the list of the greatest women athletes of the 20th Century and National Girls and Women Sports Day is celebrated around the U.S. in the first week of February in her honor, first started on Feb. 4, 1987. Because she wore No. 7 for the U.S. team, Hyman has inspired many others to sport No. 7 and the list is included on FloHyman.com.

Jay Schroeder, UCLA football quarterback (1980):

The two-sport star at Palisades High in the Pacific Palisades thought baseball would be his future. The Toronto Blue Jays made him the third overall choice in the 1979 MLB Draft, destined as a catcher. And from 1980 to ’83, Schroeder played rookie ball and Single-A. But that’s as far as it went. As Granada Hills grad John Elway was showing how he could be the quarterback at Stanford but still have a minor-league baseball career with the New York Yankees system, Schroeder came to UCLA to play quarterback as a freshman in 1980, backing up Kennedy High’s Tom Ramsey. Schroeder started once, and got into nine games — including the season-ender against USC when, coming off the bench to replace Ramsey, he threw for two touchdowns, including the game-winning 58 yarder that deflected to Freeman McNeal off USC’s Jeff Fisher, and claim a 20-17 victory. His only year as the Bruins QB: 37 of 65 passing for 634 yards, four TDs and three interceptions. After that, Schroeder decided to focus just on baseball, but after four years never getting higher than Single A, he ended it — as the NFL’s Washington Redskins quietly made him a third-round pick in the ’83 draft to be Joe Theismann’s backup. Schroeder got to start when Theismann had his career-ending injury on a Monday Night game, went to the 1986 Pro Bowl when he threw for 4,109 yards and was traded to the Los Angeles Raiders, spending five seasons and wearing No. 13. He led them to a 12-4 record and the AFC title game in 1990. Schroeder retired in 1994, having thrown for more than 20,000 yards as a quarterback. Starting in 2000, Schroeder worked as a high school football coach, including Oaks Christian High in Thousand Oaks.

In a 1991 column, the Los Angeles Times’ Jim Murray wrote about Schroeder, a Raider at that point as he was competing for his spot against Todd Marinovich: “You first look at Jay Schroeder with a football in his hand and you want to ask him, ‘What’s the matter, surf not up anymore?’ You wonder what he did with the board and why he isn’t out on the Banzai pipeline instead of the Denver goal line. He has the platinum hair, the wide shoulders, the powerful arms. He’s almost the poster California beach boy. … Schroeder has been as enigmatic as a map of Russia. Like the little girl with the curl, when he is good, he is very, very good. When he’s not, he throws interceptions. … Schroeder can look like a combination of Roger Staubach and Joe Montana one time and a combination of Laurel and Hardy another — sometimes in the same game.”

Perry Klein, Palisades High School football quarterback (1986 to 1987):

In a Feb. 8, 1989 edition of the Daily Breeze, Perry Klein said as he was winding down his senior year at Santa Monica High that that “I don’t care now” that people call him a high school mercenary athlete. “I cared about what people thought when I first transferred from Palisades,” he said. “They think I’m an idiot just doing what I want. But that’s the point. I’m doing what I want and it’s none of their business.” In 1985, as a ninth grader at Malibu Park Junior High, Klein was able to join the Santa Monica High soph-frosh football team, but he quit. He got a permit to attend Palisades High. Playing mostly defensive back in 1986, Klein’s junior year of ’87 saw him go to quarterback and set a national high school passing records with 323 completions, 483 attempt in 12 games, which accounted for a state-record 3,899 yards. The 37 touchdowns he threw that year were close to the state record of 42 that Pat Haden threw at Bishop Amat in 1970. In a win over L.A. Jordan, Klein also set the national record in pass completions in a game (46; in 49 attempts, completing 26 in a row at one point). In that game, he set a state passing record with 562 yards. He was the L.A. City 3A Section Player of the Year.

In April of 1988, Klein transferred in the middle of the L.A. City volleyball season from Palisades to Carson High. By the fall of ’88, he told Palisades coach Jack Eptein he wanted to come back, practiced one day, and the next day, returned to Carson High’s football team, helping the Colts to a 4A title and being named California State Player of the Year.

In February of 1989, Klein transferred back to Santa Monica High to play volleyball. Klein would play college football at Cal for three years, leave in the middle of the 1992 season, play at Santa Monica College and transfer to Division II C.W. Post in Brookville, N.Y. After setting more record as a college senior, he drew the attention of the NFL’s Atlanta Falcons to select him in the fourth round of the 1994 Draft.

He played in just two games over two seasons in the NFL, was waived, and joined the Amsterdam Admirals in the World Football League.

Julio Urias, Los Angeles Dodgers pitcher (2016 to 2023):

The left-hander from Culiacan, Mexico picked up Cy Young votes for leading the NL with 20 wins in 2021 (against just three losses) and a league-best 2.16 ERA in 2022 (to go with a 17-7 season). The 23-year-old was also on the mound when the Dodgers clinched the truncated 2020 World Series title during the COVID season. But he was placed on the suspended list in September of 2023 and granted free agency that fall after he was arrested in a domestic violence charge. He pleaded no contest to one count and was placed on probation, community service and counseling, effectively cutting his ties from the Dodgers, and the team tried to erase as much imagery of him as it could prior to the 2023 playoffs. But for some, this is a tough thing to let go.

Frankie Kelleher, Hollywood Stars outfielder (1942 to 1954): A .284 career hitter in the Pacific Coast League with 234 homers and 876 RBI, he was inducted into the PCL Hall of Fame in 2004, a quarter-century after his death in 1979 at age 62 His two brief stints in the majors — 38 games with the Cincinnati Reds in 1942 and another nine games in mid-1943 — saw him hit .167. Kelleher’s years between 1947 and 1951 were among the most productive for a minor-league hitter in history. In 750 games in those five seasons, he notched 143 homers, and 519 RBIs. He also scored 463 runs and hit .281. His .333 average in 1948 marked his highest average since his first season as a pro with Akron in 1936, and 1950 was his 40-homer season for the Stars, who retired his No. 7.

Chase Utley, UCLA baseball infielder (2001): The Long Beach Poly standout wore No. 27 during his freshman (’98) and sophomore (’99) seasons, switched to No. 7, hit .382 and capped his three-year career with helping get UCLA to the 2000 NCAA Super Regionals at Louisiana State. He had a .342 career batting average and twice earned All-Pac-10 team honors before he was picked in the first round (15th overall) of the 2000 MLB Draft by the Philadelphia Phillies. Then ended his 16-year MLB career playing for the Dodgers (2015 to 2018). A 2010 selection to the UCLA Athletic Hall of Fame.

Tom Wilson, Los Angeles Dodgers catcher (2004): The last Major League at-bat he had was in Game 1 of the ’04 NLCS — and he hit a home run. The Troy High of Fullerton and Fullerton College catcher was a mid-August pickup from from the New York Mets’ roster to join the NL West-champion Dodgers as a back up Paul LoDoca. Wilson only got into nine games at the end of the regular season. In the NLCS, with LoDoca injured and Brent Mayne starting Game 1, the 33-year-old Wilson came into catch in the sixth inning. He got an at-bat in the ninth against the Cardinals closer Jason Isringhausen and refused to be the last out — Wilson hit a two-out solo homer to account for the final score of 8-3 in St. Louis’ favor at Busch Stadium. The Dodgers were eliminated, four games to one. Wilson was released. After his retirement, Wilson became a New York Yankees scout.

Ron Cuccia, Los Angeles Wilson High football quarterback (1975 to 1977): Leading his teams to a combined 39-0 record and three straight L.A. City Division 3A titles, the 5-foot-9 Cuccia established what was then the national record for passing yards — 8,804 — along with 91 touchdowns. His total offense was 11,451 yards. It didn’t hurt that his father, Vic, was the Wilson coach and would have the home field named after him, honored by the community of El Sereno, east of downtown L.A. and not far from the San Gabriel Mission. Wilson got some national attention in a 1977 game against Lincoln when the Mules led at halftime, 63-0. Lincoln never returned from the locker room, deciding to forfeit. Cuccia had no major college scholarship offers, and gravitated to Harvard University. Upon arrival, the school newspaper, the Crimson, asked: “Is it true you had more publicity than any athlete ever in California?” “Probably in the whole country,” Cuccia responded. Cuccia’s national high school passing records would eventually be broken by … Todd Marinovich.

We also have:

Jimmy Clausen, Oaks Christian High school quarterback (2003 to 2006)

Carmelo Anthony, Los Angeles Lakers forward (2021-22)

Zenon Andrusyshuyn, UCLA football kicker (1967 to 1969). A great story on his life as a Bruin from the L.A. Times in 2014.

Buck Rogers, Los Angeles Angels catcher (1961 to 1969); California Angels manager (1991 to 1994)

Mike Murphy, Los Angeles Kings right wing (1973-74 to 1982-83)

Tomas Sandstrom, Los Angeles Kings right wing (1989-90 to 1993-97)

Eddie Olczyk, Los Angeles Kings center (1996-97)

James Loney, Los Angeles Dodgers first baseman (2006 to 2012) Also wore No. 27 and No. 29 in ’06

Dick Stuart, Los Angeles Dodgers first baseman (1966)

Paul Konerko, Los Angeles Dodgers first baseman (1998) Also wore No. 66 in 1997.

J.D. Drew, Los Angeles Dodgers outfielder (2005 to 2006)

Rick Burleson, California Angels shortstop (1981 to 1986)

Dave Chalk, California Angels shortstop (1973 to 1978)

Anyone else worth nominating?

Very well done! A future #7 candidate: Blake Snell.

On Thu, Nov 13, 2025 at 9:21 AM Tom Hoffarth’s The Drill: More Farther Off

LikeLike