This is the latest post for an ongoing media project — SoCal Sports History 101: The Prime Numbers from 00 to 99 that Uniformly, Uniquely and Unapologetically Reveal The Narrative of Our Region’s Athletic Heritage. Pick a number and highlight an athlete — person, place or thing — most obviously connected to it by fame and fortune, someone who isn’t so obvious, and then take a deeper dive into the most interesting story tied to it. It’s a combination of star power, achievement, longevity, notoriety, and, above all, what makes that athlete so Southern California. Quirkiness factors in. And it should open itself to more discussion and debate — which is what sports is best at doing.

The most obvious choices for No. 92:

= Rich Dimler, USC football, Los Angeles Express

The not-so-obvious choices for No. 92:

= Harrison Mevis, Los Angeles Rams

= Rick Tocchet, Los Angeles Kings

= Don Gibson, USC football

The most interesting story for No. 92:

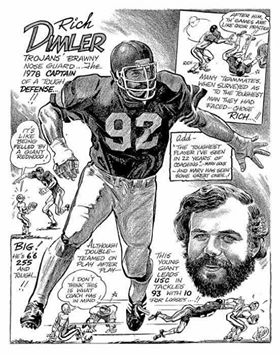

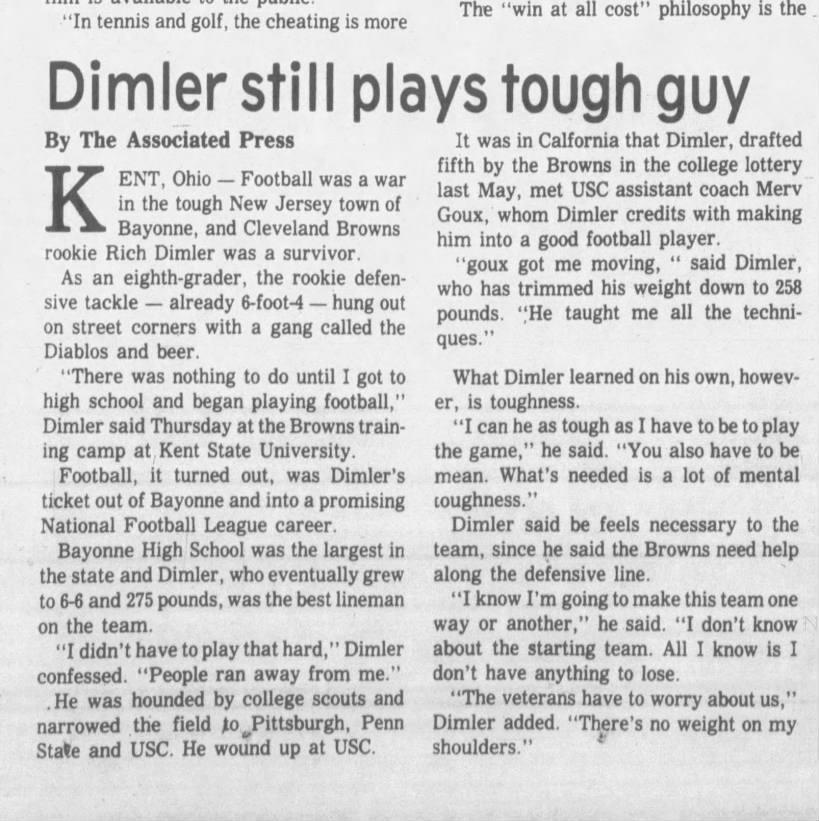

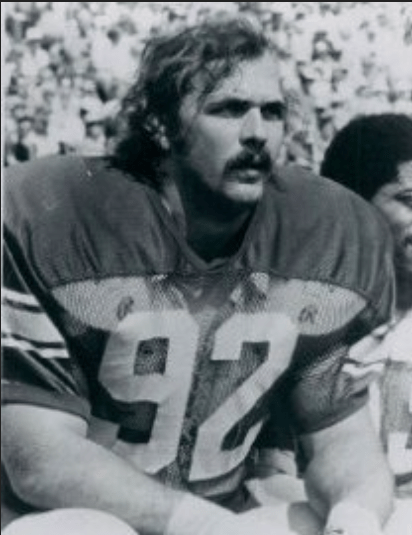

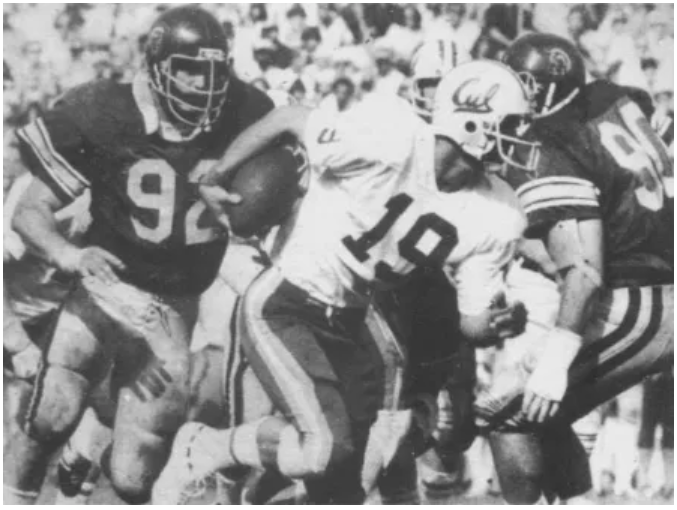

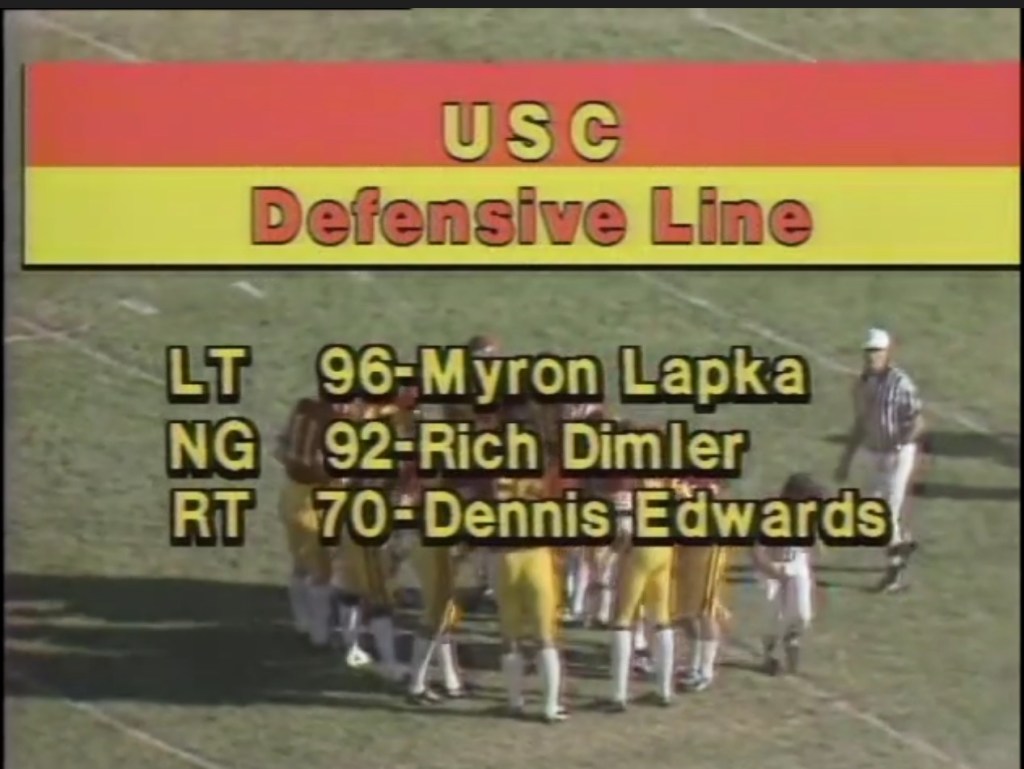

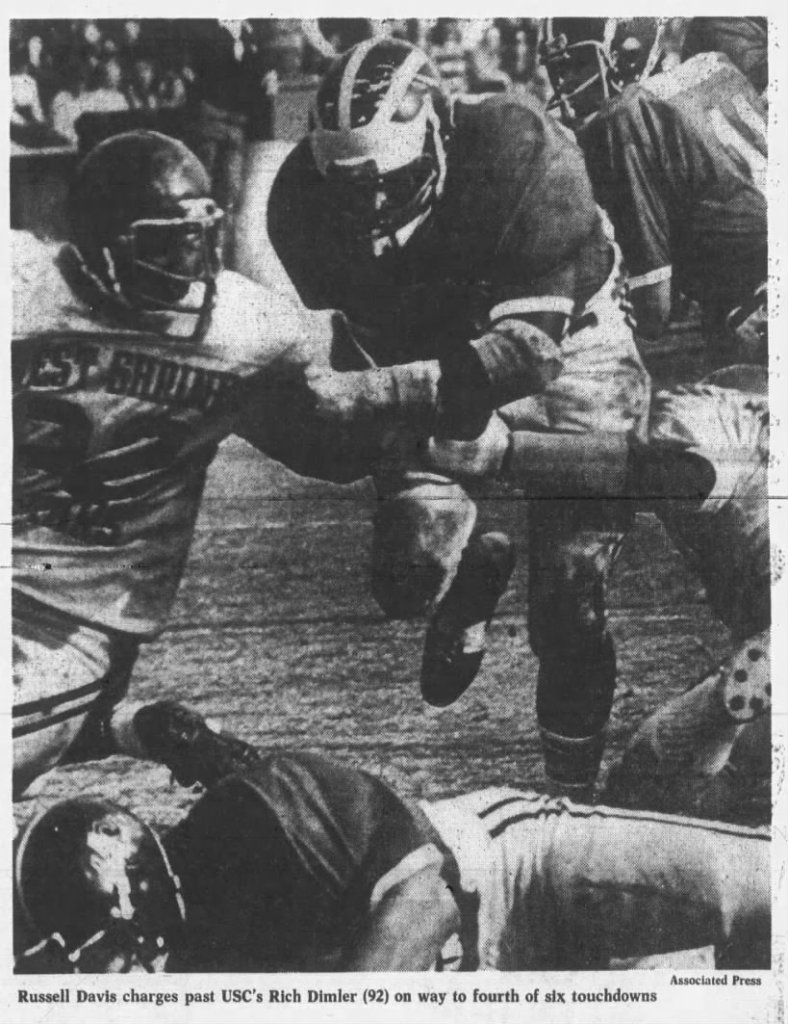

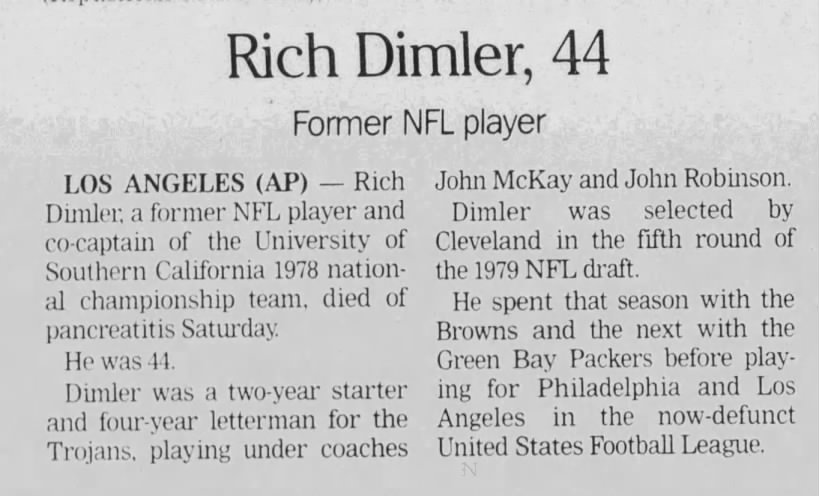

Rich Dimler, USC football nose guard (1975 to 1978), Los Angeles Express defensive tackle (1983 to 1984)

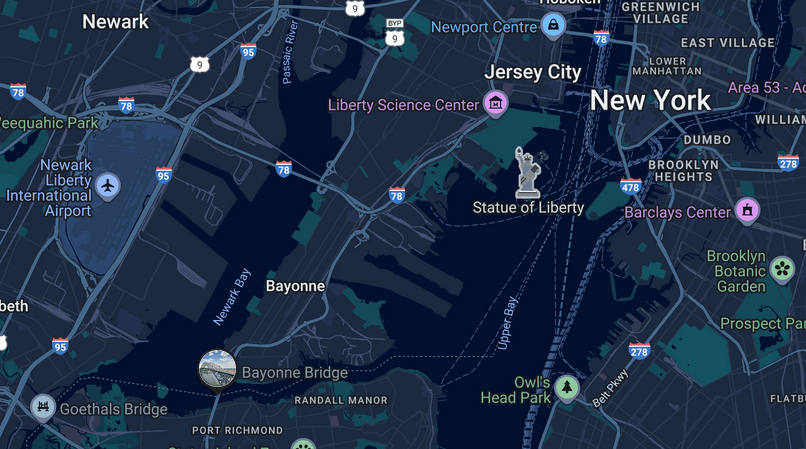

Southern California map pinpoints:

Los Angeles, Glendale, Inglewood, Hawthorne, Torrance, Rancho Palos Verdes

Raise a glass to Rick Dimler. With caution.

The fact he made it through 44 years of roughhousing, and once heralded by USC defensive line coach Marv Goux as “the toughest player I’ve seen in 22 years of coaching” while playing on four straight Trojan bowl victories, is worthy of a toast.

But then again, there was the time when his home town in New Jersey tried to throw a parade in his honor, and it didn’t end well.

Homecomings can be problematic if the honoree celebrates too early and too often.

In March of 1979, Dimler was living off the fame of finishing his four years of football at USC, capped off by a 12-1 season, co-captain of the defensive squad that was highly effective in a Rose Bowl win over Michigan, and giving the Trojans a national championship in the eyes of many voters of such polls.

At this point, Dimler was back visiting friends and family in Bayonne, New Jersey. The cityfolk were finalizing plans for what would be Rich Dimler Day — a parade in his honor, a key to the city, the red-carpet treatment. Beers hoisted and thrown back as he could now look forward to what the NFL might bring.

The party was set for April, but, again, Dimler put himself in a situation that had penalty flags flying all over the place.

On March 12, Bayonne police say they saw Dimler in a car racing another car right down Broadway through the city, and started chasing him at 2 a.m. Dimler, according to the authorities, ran three red lights trying to escape. The other car got away. Dimler was hauled in.

At that point, the 6-foot-6, 260-pound Dimler had a dim view on how this might be a teachable moment.

“I’ll have your jobs; I’ll have both your jobs!” Dimler was said to have screamed at the officers, pushing one of them away. He was eventually accused of striking a patrolman in the chest at police headquarters and deemed “unruly” while in the jail cell.

“He flunked his breathalyzer test in flying colors,” said Lt. Vincent Bonner said in newspaper accounts. The .22 result was well above the legal limit of .15.

As soon as Dimler was out on bail facing charges of assault and battery and creating a disturbance, reporters covering the incident discovered he had been arrested just a month earlier in Los Angeles on driving under the influence, but no charges were filed.

Those digging further into his legal history found a disturbing incident in 1973, the year before he left New Jersey to attend USC, when Dimler, then 17, was acquitted of a death by auto charge in juvenile court. He had been charged of hitting and killing a 10-year-old girl as she crossed the street, and he left the scene. All that happened at the time was getting put on probation.

Bayonne City Councilman Donald Ahern — who happened to be Dimler’s high school coach in the mid-’70s — was asked about how all this might tarnish te upcoming day in his honor.

“He’s a good kid with a good heart; I’d be the last guy to leave the ship for that kid,” said Ahern.

If Dimler needed another character witness, in November of ’78, USC coach John Robinson was telling the Los Angeles Times’ John Hall about how the season had been progressing with Dimler in command of the defense.

“If they ever draw up a blueprint for the ideal leader,” Robinson said, “that’s Dimler.”

When Goux once remarked about Dimler’s toughness, he added: “Rich pays the price to be a good football player — he works extremely hard at it. He knows what he has to do and does it. He plays football the way the game was designed to be played.”

Journalist Scott Wolf, who has covered USC for decades, said Goux’s words “might have one of the most sought-after compliments you could seek for a USC football player.”

Notre Dame coach Dan Devine once said of Dimler, who, in 1978, led USC with 106 tackles in its first 11 games from the nose tackle position: “I don’t know that there is a better nose guard in the country than Dimler.”

Dimler played on Trojans teams that went a combined 39-10 and won the 1975 Liberty, the ’77 Rose, the ’77 Bluebonnet and the ’79 Rose Bowls. Those Trojan teams also defeated rivals UCLA and Notre Dame three times.

Dimler was far from a dim-wit. An Academic All American, he said he considered going to a vocational school to learn a trade before Ahern encouraged him to switch to college prep courses and think about football as a career.

Dimler took pride in emerging from a rough existence in the swamps of Jersey, a place better known as the home of boxer Chuck Wepner.

If Wepner was called the Bayonne Bleeder, Dimler could be the Bayonne Bully.

He also became the go-to player when a sportswriter needed a colorful quote.

“Football in high school was more like a fight than a sport,” he told reporters in May of ’79, two months after that run-in with the law and now in the Cleveland Browns’ mini-camp, a fourth-round pick of the NFL team.

“I was in a gang called the ‘Diablos’ in the eighth grade. We had about 90 to 100 guys and hung out on street corners, shot pool and drank beer. The worst I ever got was picked up for loitering, but a lot of those guys have been in big trouble.

“Football took me out of the street and now I stay out of trouble.”

Dimler told reporters about how rough it was at Bayonne, where “if you fell down, you could tell if you were on the 50 (yard line) because there was sewer plate there.”

One newspaper headline summed it up that Dimler “traded gang fights for gang tackles” on the football field.

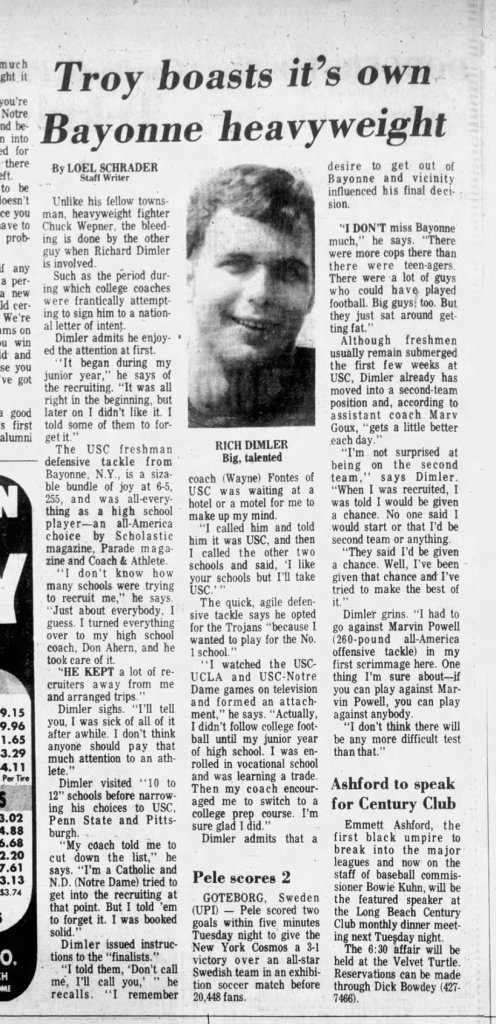

Dimler wasn’t a fan about how college recruiters came after him starting his junior year in high school, where he’d end up an All-American pick by Scholastic Magazine and Parade magazine on both the offensive and defensive line.

“I was promised things from all of them,” Dimler said. “They used to bother my girlfriend, they used to come right into the bar where I used to hang out. They really hassled me.”

Yes, he admitted to hanging out in a bar while in high school.

Eventually, Dimler picked USC and John McKay over Penn State and Pittsburgh, thanks to the recruiting of the Trojans’ Wayne Fontes.

“I’m a Catholic and N.D. (Notre Dame) tried to get into the recruiting (late),” Dimler said. “I told ‘em to forget it. I was booked solid. I told my finalists: Don’t call me, I’ll call you.”

For his freshman year, Dimler showed up at USC with a broken ankle and weighed about 280 pounds — he said he had slipped in the snow on his family’s front porch and refused to believe the doctor’s diagnosis of how severe he was injured.

By his sophomore year, Dimler was more comfortable talking to reporters. He explained what kind of target he was in public around others who wanted to show their bravery: “A man won’t say he wants to fight me. He’ll say, ‘My friend and I want to fight you.’ I walk away until they throw something at me … Football players have a bad image. People think we are all big and dumb. Actually we are probably smarter than most.”

Dimler had already earned his letter as a backup behind All-American Gary Jeter. His last two years at USC allowed him to show his abilities.

Eventually letting his hair grow longer and sporting a menacing mustache, Dimler’s first claim to fame at USC was giving a nickname to the local bar at California Pizza and Pasta Co. He called it the “502 Club.” That’s the 502 reference to the police booking for a drunk driving arrest.

Before the 1978 season, USC tailback Charles White said Dimler helped him keep perspective of his abilities.

“I don’t talk about the Heisman Trophy,” said White, who would eventually win it that season. “When I was a freshman, I made the mistake of saying I’d like to have three of them. That was before I played a game. It hit me all of the sudden, I made a mistake. I went out to practice and Rick Dimler knocked the devil out of me. That’s when I quit thinking about the Heisman Trophy.”

Dimler, who got his weight down to 240 pounds as a senior, also was paraded to the media before that ’78 season as part of the Pac-12 press junkets. In one scrum, Dimler claimed: “I don’t like winning those 49-7 games. I like games that are 9-7, 14-10, where you have to fight hard, but fair, all day. The human body is made to be abused. … I don’t feel I’ve been in a game unless I feel pain the next day. …

“In the past, the USC nose guard would keep the center and guard off the linebacker to keep him free. But offenses have changed. There’s no more man-to-man blocking. (You can) get the center to the linebacker and the guard on the nose guard. What I have to do is take the center and the guard on me, also. That way the linebacker goes free. It doesn’t take a big guy any more. Just an intelligent guy. You add some guts and you’ve got a defensive player.”

Dimler was also asked who he thought might win an upcoming September 9 matchup between UCLA and Washington.

“I think they should kill each othah,” he said in his Jersey accent.

When No. 3 USC finished the ‘78 regular season with a lethargic 21-5 win at Hawaii in early December, improving to 11-1, Los Angeles Times writer Mal Florence started his game story focused on a typical Dimler-esque quote.

“Hey, where they get those guys from? Rent-a-ref?”

Maybe the Trojans had a chip on their shoulder, feeling targeted in their last game before facing Michigan in the ’79 Rose Bowl. The team won five straight to clinch the Pac-10 title, including 17-10 over UCLA and 27-25 over Notre Dame, clinched by a field goal with two seconds left.

Dimler could carry the chip well. A nose guard not afraid of putting his nose to the grindstone.

In the ’79 Rose Bowl, Dimler had five tackles and was part of the defensive pressure put upon Michigan quarterback Rick Leach all day long in a 17-10 win most remembered for Charlie White’s phantom touchdown.

The Associated Press named 11-1 Alabama as the national champs. USC, which defeated the then-No. 1 Crimson Tide on the road in Week 3 by four points, came in at No. 2.

But in the UPI voting, USC was No. 1, and Alabama second.

USC’s lone loss was by 13 points at Arizona State in Week 5.

Voted USC’s Defensive Player of the Year, Dimler went to the East-West Shrine Game in January of ’79. He upped his profile again just by talking to the media.

“I think we have some better football in the West,” he claimed. “These guys (his teammates) are used to playing tougher schedules than the guys in the East.”

The East team, which had lost the last three in a row and seven of the last 10 to the West All-Stars, posted a 56-17 victory at Stanford Stadium.

“I haven’t changed my mind about Eastern football,” Dimler doubled down afterward. “The score didn’t mean that much.”

In August of ’79, one of his new Cleveland Browns teammates refer to him as “Demolition Dimler” as the rookie attended fall practice for his first NFL season.

“I head butt a lot,” Dimler admitted, showing a helmet that was chipped and cracked. “It’s a new technique. … It’s tough on the neck and back. In fact, my back is killing me right now.”

By the summer of 1980, perhaps the incident Dimler had with the police skirmish back in the spring of ’79 had caught up with him. A newspaper story noted that he was married and became a SoCal resident for good when he bought a home in Glendale. He said he severed all ties with Bayonne, N.J.

“I can’t tell you why, but I’m never going back,” he said.

Demons, and the department of justice, may have had something to do with that decision. A lifestyle change was healthy all around.

Dimler lasted just two years and 15 games (two starts) with the Browns. He had a tryout with the Green Bay Packers and Washington Redskins — where he kept wearing No. 92 — but nothing came of it.

Dimler circled back to Southern California to play for the United State Football League’s upstart Los Angeles Express. He played 13 games for the Express, starting five, in ’83, and five more in ’84 before the team started signing highly coveted rookies out of college. Dimler was released, having been credited with 3 ½ sacks, and had another run with the USFL’s Philadelphia Stars before he retired.

By 2000, Dimler was living in Hawthorne and owner of Snowball Express air freight and trucking in Inglewood. He was also putting up a fight against pancreatic cancer.

In early October of that year, the “rough-and-tumble” 44-year-old died in a Torrance hospital, and was buried in Rancho Palos Verdes.

His friends posted a Facebook page called “Remembering Rich Dimler.”

“Where he came from, you had to be tough just to walk down the street for breakfast,” Goux was quoted by the Los Angeles Times after Dimler’s passing. “He was the kind of guy you’d want on your side when the fight started.”

And, perhaps, when the fight ended too.

New Jersey historians fight to never forgot Dimler’s impact on local football.

In a September 1999 edition of the Newark (N.J.) Star-Ledger, Dimler was included on the newspaper’s 1900-1999 “Team of the Century,” headed by Somerville’s Paul Robeson from 1914. A month later, Dimler showed up at the third annual Don Ahern Memorial Scholarship Dinner-Dance at the Bayonne Knights of Columbus Hall, to honor his former coach.

So, in fact, he did go back one last time to Bayonne.

Dimler made history. It just depends on how history wants to remember him. With a raised beer mug? Seems appropriate.

Who else wore No. 92 in SoCal sports history? Make a case for:

Harrison Mevis, Los Angeles Rams kicker (2025): “The Thiccer Kicker” is the nickname pinned on the 6-foot, 245-pounder who came to play college football as a linebacker at the University of Missouri but also developed into the program’s clutch place kicker for four seasons. A 2025 mid-season pick-up by the Rams during their run toward the playoffs, Mevis had been undrafted and spent time on the taxi squads with Carolina and the New York Jets, as well as playing in the United Football League, before the Rams scooped him up. In Week 10, Mavis made his NFL debut, converting all six PATs in a win at San Francisco on Nov. 19 — and finished with 39 of 39 in PATs for the season. He converted three field goals but missed a late 48-yarder against Seattle in an eventual 38-37 OT loss at Seattle, which gave him a mark of converting 12 of 13 field goals in nine regular season games. In the playoffs, Mevis’ kicks of 46 and 42 yards, plus four PATs, helped produce a 34-31 NFC wild-card win at Carolina. In the NFC Divisional Round win at Chicago, Mavis nailed a 42-yarder in the snow, in overtime, to go with a regulation FG and two PATs to clinch a 20-17 win. Mevis said former Missouri punter and teammate Grant McKinniss gave him “Thiccer Kicker” name one day in the locker room before his freshman season. “It had a nice ring to it,” Mevis said. “I’m a bigger guy and a kicker, so why not?” It was a brand he could use when the NCAA approved NIL deals in 2021 as Mevis aligned with a local shop, 573 Tees, for his T-shirt deals and his merch was born. Mevis kicked all four seasons at Missouri, leading the SEC with a 26-of-28 showing (92.9 percent) in 2023 in a a season where he nailed a 61-yard field goal as time expired in a 30-27 upset over No. 15 Kansas State, propelling Missouri to a No. 8 overall AP ranking by season’s end.

Rick Tocchet, Los Angeles Kings right wing (1994-95 to 1995-96): Forty goals in 80 games for the Kings over the span of two half-seasons, coming from Pittsburgh and departing to Boston, it included a hat trick in a 4-3 win over Detroit on Feb. 4 of ’95 after the league resumed from a lockout. A four-time All Star in an 18-year career that saw him win a Stanley Cup with Pittsburgh in 1992, he was sent to the Kings in the 1994 off season for Luc Robitaille. The Kings eventually traded him to Boston for Kevin Stevens. He also wore No. 22 for the Kings in ’96.

Brandon Mebane, Los Angeles Chargers defensive tackle (2017 to 2019): Out of Crenshaw High in L.A., Mebane was a third-round NFL draft pick from Cal and was on the 2014 Super Bowl championship Seattle Seahawks. He started 51 of his 54 games with the Chargers, including 10 when the team was still in San Diego.

Don Gibson, USC football defensive lineman (1987 to 1990): Out of El Modena High in Orange, the 6-foot-3 Gibson has increased his weight to almost 270 pounds as a senior, coming back from an injury after he started all 24 games of his freshman and sophomore seasons. Don’s younger brother, Craig, followed him to USC and played center (wearing No. 61). Their father, Frank Gibson, played end at the U.S. Military Academy and was co-captain of the Cadets’ 1960 team.

We also have:

Greg Clark, Los Angeles Rams linebacker (1990)

Siale Taupaki, UCLA football defensive tackle (2019 to 2025)

Tony Colorito, USC football defensive lineman (1983 to 1985)

Anyone else worth nominating?

1 thought on “No. 92: Rich Dimler”