This is the latest post for an ongoing media project — SoCal Sports History 101: The Prime Numbers from 00 to 99 that Uniformly, Uniquely and Unapologetically Reveal The Narrative of Our Region’s Athletic Heritage. Pick a number and highlight an athlete — person, place or thing — most obviously connected to it by fame and fortune, someone who isn’t so obvious, and then take a deeper dive into the most interesting story tied to it. It’s a combination of star power, achievement, longevity, notoriety, and, above all, what makes that athlete so Southern California. Quirkiness factors in. And it should open itself to more discussion and debate — which is what sports is best at doing.

The most obvious choices for No. 95:

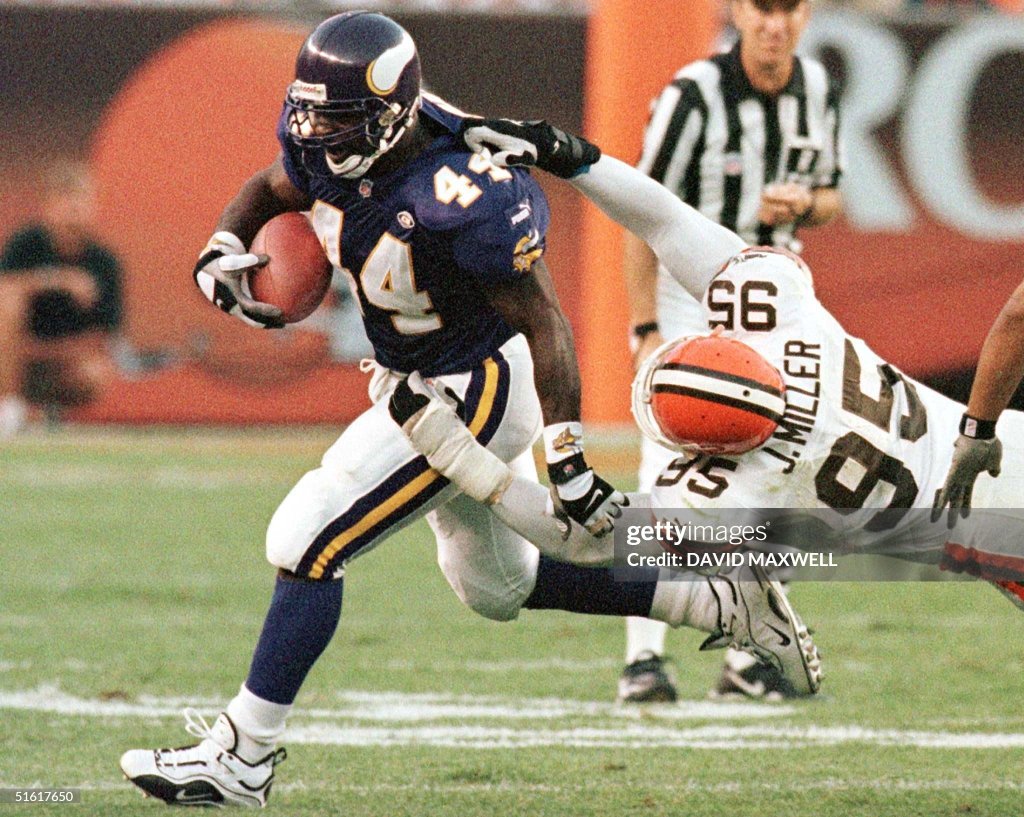

= Jamir Miller, UCLA football

The not-so-obvious choices for No. 95:

= Roger McQueen, Anaheim Ducks

The most interesting story for No. 95:

Jamir Miller, UCLA football outside linebacker (1991 to 1993)

Southern California map pinpoints:

Westwood, Pasadena

Jamir Miller’s jam at UCLA, aside from chasing down quarterbacks, seemed to be a persistent pursuit of parties. That didn’t stop until he was well into a career in pro football.

An All-American linebacker who, in just three seasons with the Bruins would lead the team in sacks each year, rack up a then-school record 23 ½ total, added 35 tackles for a loss, and was a Butkus Award finalist by the time he was done with college football, Miller said he once assessed that by his sophomore year in Westwood, “I embarked on the wild phase of my life that lasted through my second year in the NFL,” according to the Cleveland Plain Dealer in August of 2000.

That didn’t include a senior year of college in that time frame.

The 6-foot-5, 252-pounder was arrested twice at UCLA — once for possessing a loaded firearm and once for accepting stolen stereo and computer equipment. He pleaded no contest to both charges, was placed on three years probation and required to perform 100 hours of community service.

Miller also was suspended for the 1993 season opener by head coach Terry Donahue, a person who Miller credits for being most responsible for recruiting him to come to UCLA and tell his mother that her son would be taken care of. UCLA not only lost that first game of the season, 27-25, to Cal, but also the second game, 14-13, at the Rose Bowl against Nebraska, to started 0-2. That would be the last season for Miller at the school.

Miller’s missteps followed a bit of a pattern he developed as a kid growing up with a single mom in the Oakland area, trying to figure out his identity.

Jamir Malik Miller — his first and middle names mean royal warrior in Swahili — said he didn’t feel much like a warrior growing up.

“When I was younger I didn’t really like my name because it was different and a lot of people couldn’t pronounce it,” Miller told the Los Angeles Times in 1992. “They mess it up and say ‘Jamal’ and I’d go, ‘No, it’s Jamir .’

“I was in the fourth or fifth grade and I’d come home and say, ‘Mom I hate my name because no one can pronounce it.’ She told me not to worry, that I’d understand it when I grew older.

“I wanted to change my name to something like John. I wish my mother had named me something normal. But I decided to stick with it because that’s my identity. And now I’m glad she didn’t name me something normal.”

John Miller was the name of Jamir’s father. A hardened intravenous drug addict, John’s actions forced Jamir’s mother, Rhonda Hardy, to take him as a 3-month old out of their home in Philadelphia and move in with her mother and sisters in the Bay Area.

Hardy said she sensed Jamir was smart and curious, reading words in the newspaper by age 3, progressing enough that he skipped a grade in elementary school.

Jamir also knew he was hardheaded. He learned to drive at 10 and started taking his mother’s car without permission when he was 14. He would wait until she went to sleep and then drive off.

“I got busted for stealing my mom’s car,” Miller said. “I’d taken the car out a couple times at night and I’d go over to my buddy’s house and we’d go pick up girls. I’d done it so many times I thought I could get away with it easily.”

She eventually caught him, and grounded him for six months.

“That was the worst feeling I ever had in my life,” Miller said. “My mom trusted me and left her keys out and I stole them.”

Miller was expelled from the Oakland school district for fighting in the eighth grade.

“I was just being a knucklehead and rebelling,” Miller said. “That was a time in my life where I didn’t know what I wanted, so I tried everything. I was getting good grades, but I’d get suspended from school every week for fighting and cussing teachers.”

His mother gave him two choices — enroll at an all-boys Catholic high school, St. Mary’s, or attend nearby El Cerrito High, as both were just north of Berkeley.

He opted for the later, even though he had no friends there. But going out for the El Cerrito football team gave him structure.

“In a way football kept me sane,” Miller said. “I’m not saying I’m a very aggressive person toward others, but the discipline part of football has helped me to learn when to talk it out or when to slug it out.”

He became one of the country’s most-sought linebackers with 367 unassisted tackles, 32 sacks, three interceptions, six fumble recoveries and 22 forced fumbles in his high school career. He also made it to the state finals as a junior in the 200-meter dash and 4×100 relay.

Miller’s decision to go south to UCLA was to “get away from my friends and the people I knew and start fresh,” he said. “I needed to grow up.” He said moment he set foot on the campus, “it was beautiful – everything I thought a college should be.”

The only true freshman on UCLA’s defense in 1991, used primarily as a pass rusher in the nickel defense, Miller had five sacks, tied for the team lead with linebacker Arnold Ale, and was named the Bruins’ outstanding rookie defender.

The transition to the classroom was another issue. He was on academic probation with a less than a 2.0 grade-point average in his first quarter at UCLA.

“I was on the verge of getting kicked out,” Miller said. “At El Cerrito I didn’t study or go to class. If I did go to class, I didn’t pay attention, but I still got B’s and A’s. But I came here and I had to study. I learned that I couldn’t cram at the end and expect to get a good grade. I guess it was all the stuff that the average freshman goes through.”

Miller started as a sophomore in a 37-14 season-opening win over Cal State Fullerton, then recorded three sacks and batted down a pass in UCLA’s 17-10 win over Brigham Young in Week 2. At that point, UCLA defensive coordinator Bob Fields was comparing Miller to Kansas City Chiefs linebacker Derrick Thomas as well as Carnell Lake, the former UCLA star who had gone on to star with the Pittsburgh Steelers.

“I think that Jamir will develop into an outstanding player,” said Field.

In 1993, Miller’s time in the spotlight in a positive light came when he recorded 4 ½ of the team’s 10 sacks against BYU quarterback Steve Walsh during a 68-14 win. Miller had come off a concussion suffered in a win over San Diego State and had been out with the flu the prior week. That was amidst a seven-game UCLA win streak.

The Los Angeles Times noted that Miller had, by that point, sacked Walsh 11 ½ times going back to the previous season (three) as well as when they faced off in the 1991 Shrine All Star game as high school seniors.

UCLA was ranked as high as No. 10 by the 10th week of the ’93 season — the one that started 0-2 — and a 27-21 win over UCLA in the Pac-10 season finale was secured by a goal-line stand Miller was apart of. With 50 seconds to play, USC was 2 yards from scoring a go-ahead touchdown but a Rob Johnson pass was picked off in the end zone by UCLA’s Marvin Goodwin. On the play before that, Miller stopped USC freshman tailback Shawn Walters from diving into the end zone for a touchdown.

“They didn’t run to my side the entire game,” Miller told the Pasadena Star News. “When we talked about the play-action pass in the huddle (before the final play), the tight end pop pass, I told everyone to watch out for that.”

The Daily Breeze reported that Miller, who had two of UCLA’s seven sacks in the win, was pacing up and down the field yelling at his teammates to watch for the play before Goodwin’s interception.

“We needed a wake-up call,” Miller said.

On the front page of the Los Angeles Times the next day, Miller was the main photo, holding a rose in his mouth. The win vaulted the 8-4 Bruins through a three-way tie for the conference title and into the 1994 Rose Bowl, where they eventually absorbed a 21-16 loss to No. 9 Wisconsin.

Miller decided that, even though he was 20 years old, all the run-ins and issues were cause for another change in scenery. Rather than come back for a senior season, Miller saw the prospects of millions of dollars to spend with a new NFL contract — an agreement that came with Arizona and head coach Buddy Ryan after a prolonged holdout that netted him a four-year deal worth a reported $5 million, plus a $2 million bonus.

“I took everything like it was a joke,” Miller said, who kept going back to UCLA to party, and then finding new friends in Arizona to drink and smoke pot with. “When you give a 20-year-old kid that much money, things are going to happen,” he said.

By the start of his second season, Miller was hit with a four-game suspension for violating the NFL’s substance-abuse policy for marijuana use, the second time he had tested positive. One more positive test and he’d be banished for a year.

Miller decided to quit smoking pot and dropped his former friends “like a hot rock,” he said. Swearing he would never get into cocaine or crack because “I saw what it had done to other people in my life,” Miller had his father’s history to learn from.

“I’m a very headstrong person,” he said. “Once I make up my mind to do something, it’s done.”

His time at UCLA led him to finding his future wife, Raquel, a law school student who “didn’t approve (of my partying), but she loved me.” Miller said it wasn’t until his daughter Ashlynn was born in 1996 that he understood “t wasn’t just about me anymore. The light went on.”

Miller tried to reconnect with his father, who had been on his deathbed in 1997, and finally reached him by phone.

“There’s a lot of things you want to say after 26 years,” Miller said. “We had a long conversation, but by that time I was a father myself and I couldn’t see eye to eye with it. He did what he had to do, but the only one that suffered was me.”

Miller played five years with Arizona through 1998 — he had two sacks and 11 solo tackled in two playoff games — but instead of signing an extension, he went as a free agent to Cleveland for four years and $18.3 million. He stayed three season with the Browns, leading the team with 118 tackles and 94 solo tackled in 1999. A Pro Bowl season in 2001 came when he recorded 13 sacks (more than in the previous three seasons combined), an interception and four forced fumbles. Miller ruptured his right Achilles tendon during a 2002 exhibition game that knocked him out for that season and led to his retirement in May of 2003 at age 29 after trying to come back with Baltimore and Tampa Bay. At that point, Miller was the only Browns player to make the Pro Bowl since the team rejoined the NFL in 1999.

“The good part about it is that I had a chance to play for nine years and I had a great career and I did finish my career on top as an All-Pro,” he said. “I reached all my goals as a player except one, and that’s a Super Bowl ring.”

In 2012, Miller returned to the Rose Bowl for UCLA’s Oct. 12 game against Utah (a 21-14 win) to serve as an honorary captain. He had started a nutritional snack company by then.

But what seemed most important to him was how, in 2004, Miller, whose LinkedIn account lists him as a “philanthropist and investor” in the greater Phoenix area, established the Jamir Miller Foundation to benefit battered women. It said it was “a subject that hits really close to home.”

Who else wore No. 95 in SoCal sports history? Make a case for:

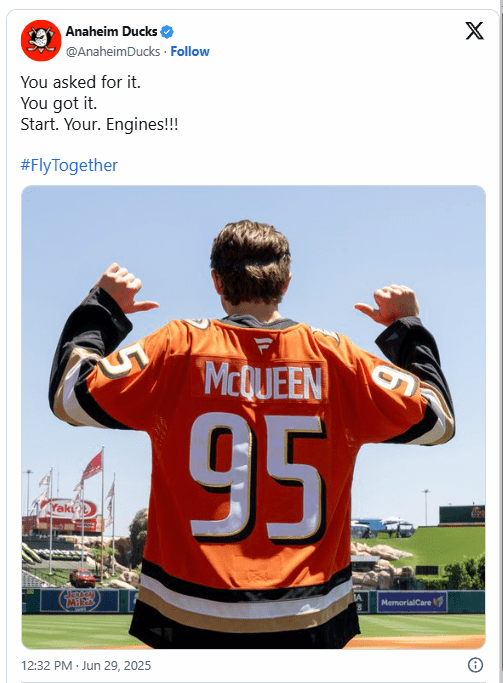

Roger McQueen, Anaheim Ducks center / draft pick (2025):

When the Anaheim Ducks selected the 19-year-old from Saskatoon, Saskatchewan with the 10th overall pick in the June 2025 NHL draft held at the L.A. Live Peacock Theater, someone in the organization started to connect the dots and figured out they could drive home the Hollywood spin immediately.

The 6-foot-6 center was eventually given uniform No. 95 to parade around — the same number that Lightning McQueen sported in the Disney/Pixar “Cars” movie franchise — and flown via helicopter to Disneyland to get some photo opps. It should be noted: That number emerged a direct reference to the year Pixar released its first feature film, “Toy Story,” in 1995 to start its animation legacy.

On June 29, McQueen was throwing out the ceremonial first pitch at Angel Stadium before the Angels’ game against the Washington Nationals. But soon after, McQueen decided that he could take advantage of a new rule that allowed Canadian junior hockey players to transition to NCAA hockey rather than sign with an NHL team right away. As a result, McQueen, who played four seasons for the Brandon Wheat Kings of the Western Hockey League from 2021-22 to 2024-25, went to Providence College to play. Making some NIL money. Wearing No. 29.

Do his plans include after that to join the Ducks? It remains to be seen if he flies West for an upcoming winter.

We also have:

Dennis Edwards, Los Angeles Rams linebacker (1987)

Walt Underwood, USC football defensive tackle (1975 to 1977)

Anyone else worth nominating?

1 thought on “No. 95: Jamir Miller”