This is the latest post for an ongoing media project — SoCal Sports History 101: The Prime Numbers from 00 to 99 that Uniformly, Uniquely and Unapologetically Reveal The Narrative of Our Region’s Athletic Heritage. Pick a number and highlight an athlete — person, place or thing — most obviously connected to it by fame and fortune, someone who isn’t so obvious, and then take a deeper dive into the most interesting story tied to it. It’s a combination of star power, achievement, longevity, notoriety, and, above all, what makes that athlete so Southern California. Quirkiness and notoriety factor in. And it should open itself to more discussion and debate — which is what sports is best at doing.

The most obvious choices for No. 79:

= Jonathan Ogden, UCLA football

= Bob Golic, Los Angeles Raiders

= Rob Havenstein, Los Angeles Rams

= Jeff Bregel, USC football

The not-so-obvious choices for No. 79:

= Gary Jeter, USC football

= Coy Bacon, Los Angeles Rams

The most interesting story for No. 79:

Forest Whitaker, Palisades High football defensive tackle (1976 to 1978)

Southern California map pinpoints:

Pacific Palisades, Carson, Hollywood

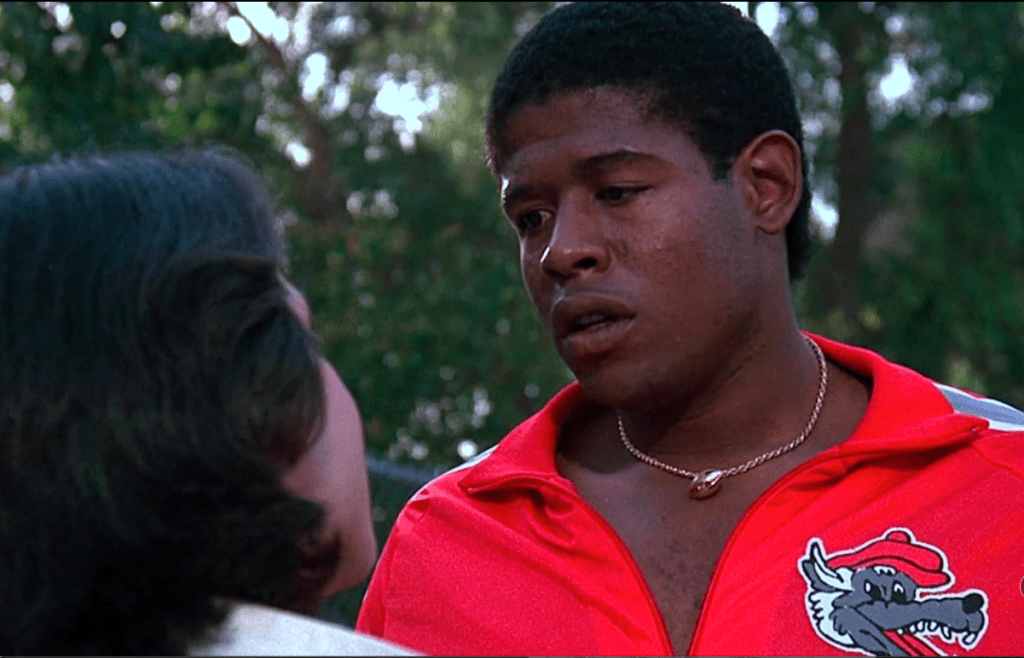

There’s five minutes of mayhem in the iconic 1982 teen flick “Fast Times at Ridgemont High” where Forest Whitaker is allowed to show a full range of acting — and athletic — skills, something he would eventually harness decades later with an Oscar-worthy resume.

As Ridgemont High’s star linebacker Charles Jefferson, wearing No. 33 on his jersey and lettermen’s jacket, Whitaker goes from mild-mannered to maniacal mayhem during a fast-and-furious turn of events.

It wasn’t a real stretch for Whitaker to take on that role.

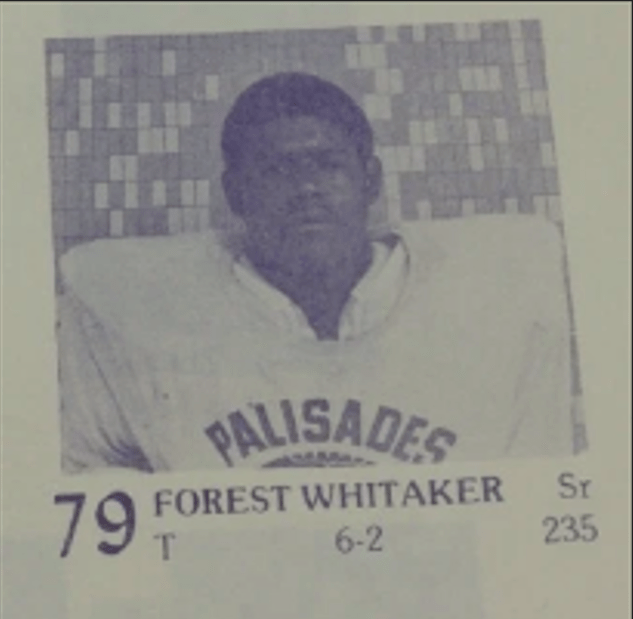

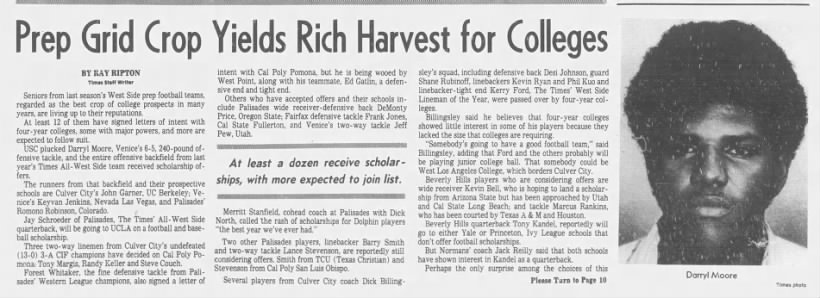

Just a few years earlier, he was an All-L.A. City defensive tackle at Palisades High, wearing No. 79. He would go off to Cal Poly Pomona on a football scholarship.

Maybe some special effects are used during the movie’s football game scene, allowing Jefferson to launch himself in slow motion over the Lincoln High offensive line and tackle the entire backfield.

One by one, Jefferson knocked out the opposing team to the delight of the Ridgemont student section, many wearing buttons that read “Assassinate Lincoln.”

There were more cinematic knockouts to come for Whitaker.

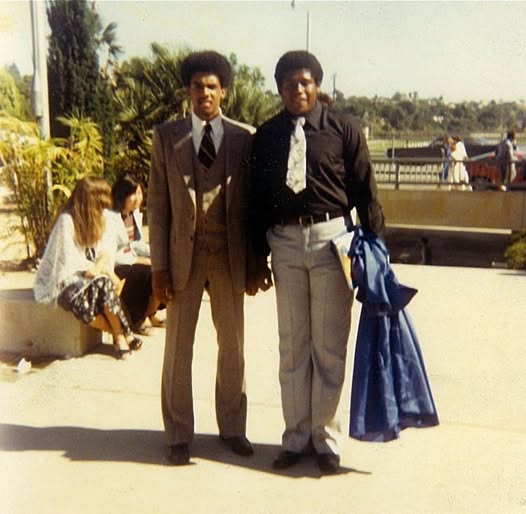

Forest Steven Whitaker, born on July 15, 1961 in Longview, Texas, moved with his family to Carson at age 4. His mom, Laura, was a special ed teacher and his father, Forest, sold insurance.

Rather than have him attend a school in L.A.’s tougher inner city, Whitaker’s parents figured out a way to have him go to Palisades High in Malibu, which could be an hour-long ride in traffic one way.

Whitaker once said his parents’ decision may have saved his life.

“If I hadn’t gone there (to Palisades), who knows what would have happened to me — my uncle was killed by a cop, and I saw three friends get killed,” Whitaker was quoted in a Washington Post story as he was at a symposium at the National Press Club in Washington, D.C. This was in 1993 as a gritty crime drama for HBO called “Strapped” came out, Whitaker’s directorial debut.

Pali, bordered by Sunset Boulevard and Temescal Canyon Road, just a mile from Will Rogers State Beach, plays its football games at a place it calls Stadium by the Sea.

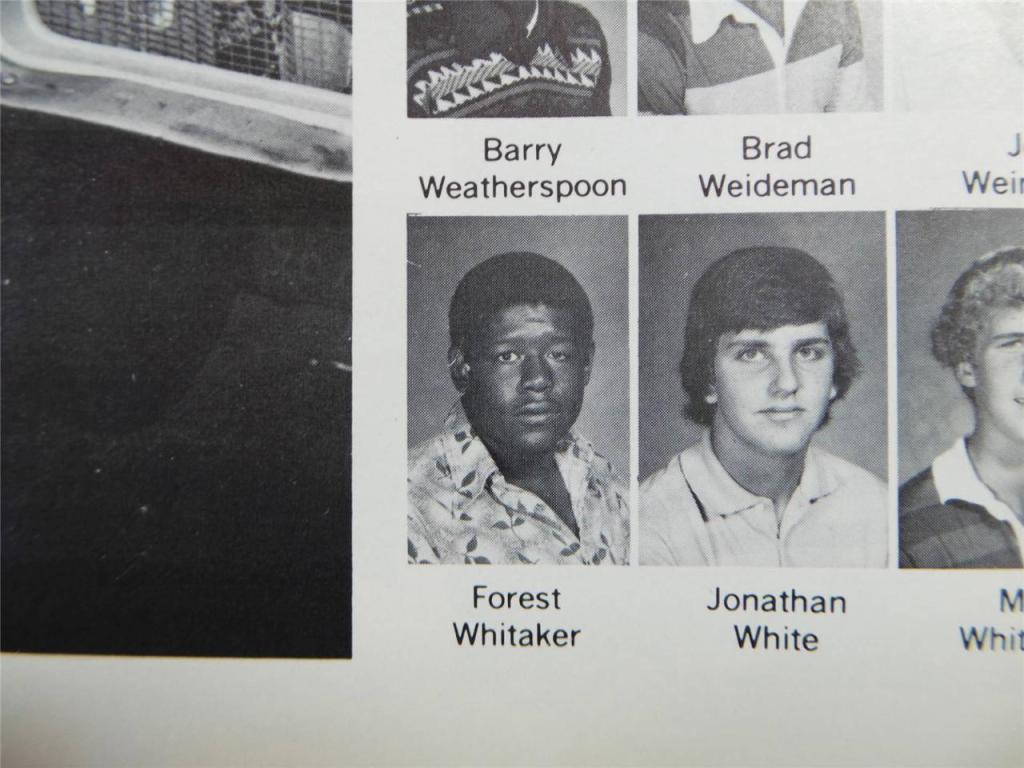

Football wasn’t the only lure for Whiaker at Palisades High. He sang in the choir and was part of the Science Fiction club. He took the stage as well.

He was in Pali’s production of the Dylan Thomas’ play, “Under Milk Wood.” He also played in “Jesus Christ Superstar” in 1978 as Simon Zealatos. He was a bartender and dancing gorilla in “Cabaret” in 1979, according to the Facebook account, “Pacific Palisades – Remember When.”

David Doherty, part of the school’s production crew, remembered how Whitaker “fell into the orchestra pit in the gorilla costume” one night but the head stayed onstage and rolled around on the floor. “When he stood up, he was able to rise into the gorilla head and climb back onto the stage to finish the song, ‘If you could see her through my eyes.’ ”

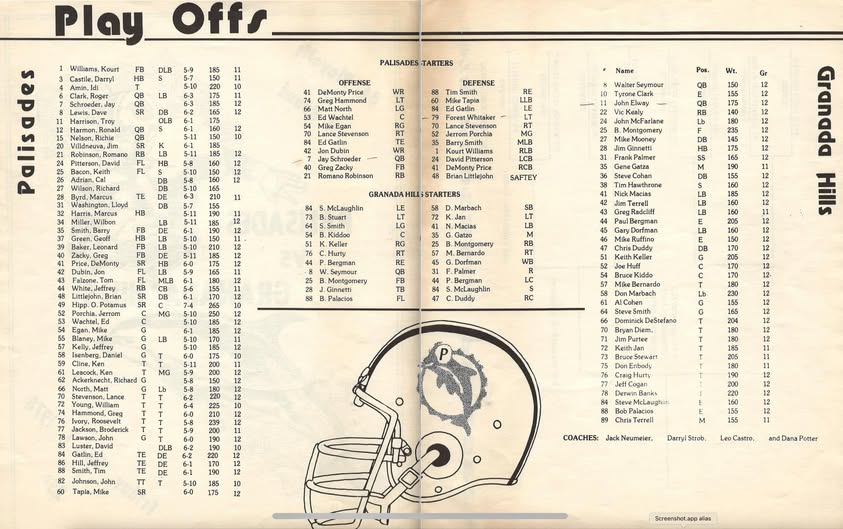

The Palisades High football team during Whiaker’s time had some star talent — future UCLA quarterback Jay Schroeder led the offense for the Western League champs. The school would end up playing against John Elway’s Granada Hills High team in the City playoffs.

Whitaker was named to the L.A. Times’ All-Westside first team during his senior season with the writeup: “The 6-3, 230-pound Whitaker displayed great agility and aggressiveness. If teams ran away from him, he still managed to get to ball carriers and make tackles all over the field.”

Whitaker reportedly turned down an offer to go to West Point, which recruited him along with Pali teammate Ed Gatlin. Whitaker also had feelers from UCLA and Arizona.

But as Whitaker once explained, his enrollment at Palisades High bent a lot of CIF rules. At that time, it was more common that one liked to believe that student-athletes could skirt school borders by having a parent move into a new district, or find the address of a family or friend to use as a home base.

These days, it would be a moot point. In 1993, Palisades Charter High School was its official name, making it one of the first group of Los Angeles Board of Education entities in California to convert to that status, creating full independence as it was facing closure in 1992 prompting parents and staff to see charter status. In 2005, Palisades was recognized as a California Distinguished School, and 10 years later, it was named one of America’s Best High Schools by Newsweek and U.S. News & World Report. As a result, students come from all areas of Southern California to attend.

But in 1979, Whitaker insisted that some colleges to withdrew their offers or stopped recruiting him when they found out what he had done.

“I should have gone to Compton High, but my mother wanted me to go to a good school,” he said. “I got screwed out of a football scholarship to the one school I wanted to go to. I had 40 scholarship offers when I was in high school and I wanted to go to the University of Hawaii.”

Instead, Whitaker went to Cal Poly Pomona. But his time on the football field didn’t last long. He suffered a back injury as a freshman.

Reconsidering his career path, Whitaker changed his major to music, eventually transferring to the Thornton School of Music at USC to study opera, an aspiring tenor. His mother had been a USC graduate with a degrees in special education and psychology.

Part of Whitaker’s time at Palisades High was as a member of the Madrigals singing choir, and he toured England with the Cal Poly Chamber Singers in 1980.

From there, Whitaker was accepted into the Drama Conservatory at USC and graduated with a Bachelor of Fine Arts in acting in 1982. He then took a post-graduate course at Drama Studio London at its Southern California branch.

Neither of those schools had their own football teams. Whitaker was fine with that.

Whitaker said he learned a powerful lesson while at USC, however, that changed how he approached his new craft.

“The faculty here taught my classmates and me that while we existed as individuals, our greatest successes as artists would come from our capacity to channel our talents into the dynamics of an ensemble,” he said. “Our greatest artistry wasn’t going to be found in isolation.”

During that time, Whitaker jumped into the “Fast Times at Ridgemont High” ensemble as his first film experience. Jennifer Jason Leigh, the daughter of actor Vic Morrow, was also in Whitaker’s classes at Palisades and that became her movie debut as well. Included were up-and-coming stars Sean Penn, Phoebe Cates and Nicholas Cage.

Whitaker’s first extended scene is when he arrives on the Ridgemont High campus — we are to assume it’s somewhere in the San Fernando Valley — and finds his prized Camaro Z28 vandalized. The front end was bashed in. The driver’s side was spray painted “Lincoln Rules.” The windshield was spray painted “Die Ridgemont.”

“Jefferson’s really going to make Lincoln pay for this,” a student could be heard. “That guy’s going to totally destroy them. Annihilate. You know what I mean?”

What Jefferson didn’t know about the car damage was purposeful.

His younger brother (played by Stanley Davis Jr., but whose character had no name in the film) had been out joy riding with stoner classmate Jeff Spicoli behind the wheel. Weaving through traffic, Spicoli swerved to avoid an oncoming truck, diverted into a construction zone and crashing into a pile of cinder blocks. That led to another memorable screen exchange:

“My brother’s gonna kill us! He’s gonna kill us! He’s gonna kill you and he’s gonna kill me, he’s gonna kill us!”

“Hey man, just be glad I had fast reflexes!”

“My brother’s gonna shit!”

“Make up your mind, dude, is he gonna shit or is he gonna kill us?”

“First he’s gonna shit, then he’s gonna kill us!”

“Relax, all right? My old man is a television repairman, he’s got this ultimate set of tools. I can fix it.”

“You can’t fix this car, Spicoli!”

Spicoli pokes his head out of the driver’s side window and looks at the damage.

“I can fix it.”

(FYI: Stanley Davis Jr., went on to play wide receiver defensive back at Long Beach State in the late 1980s and coach professionally in the Arena Football League with the Chicago Rush.)

By making it look like members of the rival school had vandalized Jefferson’s car, Spicoli could channel Jefferson’s anger elsewhere.

Ridgemont defeated Lincoln, 42-0, for those who saw the shot of the scoreboard when Whitaker’s scene ended. The game was filmed at Van Nuys High, as was much of the school exterior scenes. Back in the day, Van Nuys might have been on the Palisades High schedule, even as the Dolphins’ usual foes were locals like Canoga Park (another school exterior used in the movie), Santa Monica, Hamilton, Fairfax, University, Venice, Westchester and Monroe.

It was the start of a winning streak in Whitaker’s Hollywood career.

In a 2019 interview for GQ magazine, Whitaker explained that as he accepted the role for “Fast Times,” he had just lost a lot of weight.

“It was mostly from starvation, from not havin’ any money,” he said with a laugh. “I gained 40 pounds to play that character, which normally would’ve been probably my size anyway. It was ironic that’s what I had to do for that part.”

Whitaker said Penn had asked him at the time to join him in a movie he was making called “Bad Boys,” a crime drama at a juvenile detention center that would come out in 1983. But Whitaker said he felt he needed to back to school to learn more about the craft of acting.

“I didn’t feel like I was good enough to be permanently put on film forever,” Whitaker said. “I was still learning (at the Drama Studio London Conservatory) just to try to understand my craft. I wasn’t ready. I didn’t like my work.”

Whitaker said he felt more comfortable doing plays at L.A.’s Mark Taper Forum with an improv group.

“I really had my own reasons for acting,” he said. “Sort of the connection between people. Like pulling away experiences and trying to understand each character, where he connected to me and then hopefully connecting to everyone. That was my intentional journey. It took a long time before I could feel like I could do that.”

By 1985, Whitaker could still pull off acting as if he was a high school student/athlete.

His second film, “Vision Quest,” asked Whitaker to play a wrestler named Jean-Pierre Baldosier, aka “Balldozer,” a teammate of Louden Swain (played by Matthew Modine) as they competed at Thompson High School in Spokane, Washington.

A year later, Whitaker was shooting pool — a naïve-looking player named Amos who outhustled Paul Newman’s Fast Eddie Felson in “The Color of Money” (1986).

The roles that quickly followed — “Big Harold” in Oliver Stone’s “Platoon” (1986), Jack Pismo in “Stakeout” (1987), Edward Garlick in “Good Morning, Vietnam” (1987 — led to his breakout portraying the life of tortured jazz icon Charlie Parker in Clint Eastwood’s “Bird” (1988), which won him the Cannes Film Festival award for Best Actor and a Golden Globe nomination.

His directing roles were in projects such as “Waiting to Exhale” (1995) and “Hope Floats” (1998).” He produced movies including “Fruitvale Station” (2013) and “Dope” (2015).

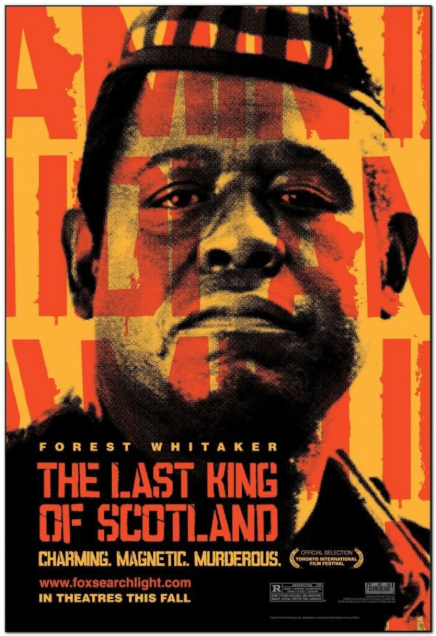

Whitaker’s defining role as an actor was the 2006 film, “The Last King of Scotland,” as Ugandian dictator Idi Amin. It got him the 2007 Academy Award for Best Actor in a Leading Role in a category that included Leonardo DiCaprio, Peter O’Toole, Ryan Gosling and Will Smith.

“When I was a kid, the only way I saw movies was from the back seat of my — my family’s car at the drive-in,” Whitaker said in his acceptance speech. “It wasn’t my reality to think I — I would be acting in movies. So, receiving this honor tonight tells me that it’s possible. It is possible for a kid from East Texas, raised in South Central L.A. and Carson, who believes in his dreams, commits himself to them with his heart; to touch them and to have them happen. ‘Cause when I first started acting it was because of my desire to connect to everyone, to that thing inside each of us — that light that I believe exists in all of us.”

Whitaker became the fourth Black man to win an Academy Award for Best Actor, joining Sidney Poitier, Denzel Washington, and Jamie Foxx.

“He is one of the finest actors of our time,” said Poitier in 2013. “I have followed his career and seen how he finds a character in every role he plays.”

He also received the Golden Globe Award, the Screen Actors Guild Award and BAFTA Award for his portrayal of Amin. That role led to Whitaker playing Desmond Tutu in “The Forgiven” (2017), Zuri in “Black Panther” (2018) and Aretha Franklin’s husband opposite Jennifer Hudson in “Respect” (2021).

In 2012, the Whitaker Peace & Development Initiative came into being to promote peace, reconciliation and social development within communities long marked by violence and conflict. The Los Angeles Press Club gave him its Visionary Award in 2013, in recognition as well for his role of Eugene Allen in “The Butler.” His star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame was cemented in 2007.

“Forest was always a fascinating combination of athletic and artistic excellence,” said Palisades classmate Jeffrey C. Kelly said on the Facebook account, “Pacific Palisades – Remember When” posted by Steward Slavin.

“As a teammate with him on the Pali football team, I always tripped that he was also a member of the Madrigals. We also attended Cal Poly Pomona together for a time, where he was also into the arts and played for our football team. I am so thrilled with his achievements.”

Who else wore No. 79 in SoCal sports history?

Make a case for:

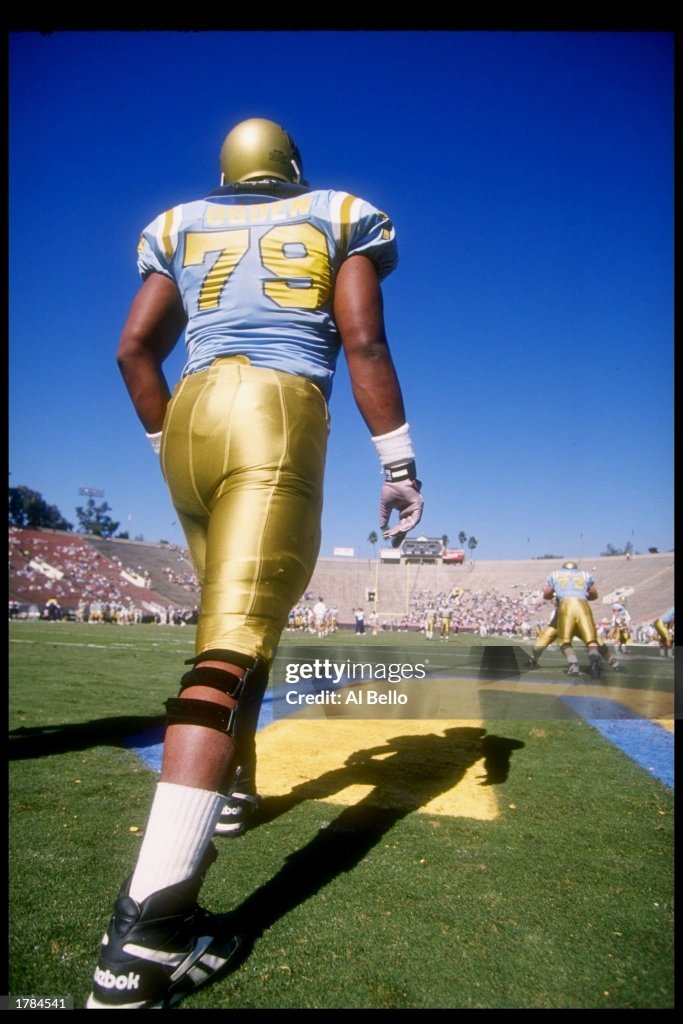

Jonathan Ogden, UCLA football defensive tackle (1992 to 1995):

Best known: By almost all measurements, Ogden is the greatest to wear No. 79 in college football history. Largely, his size helps — 6-foot-8 and 310 pounds. But it was much more he did as UCLA’s first first Outland Trophy winner in 1995. Ogden made it to the 2025 All-Time AP All American team and he was included in ESPN’s All-Time College Football All-American team to commemorate the sport’s 150th anniversary.

Slotting him at No. 121, the ESPN post noted: “It didn’t seem fair. A player that big and powerful shouldn’t be that quick and athletic. A player with that combination of size, strength and speed shouldn’t also be so smart, savvy and structured. Yet, that was Ogden, the total package for an offensive tackle, a unique combination of brains and brawn.” UCLA coach Terry Donahue, once told The Baltimore Sun that on his recruiting visit to the Ogden home in Washington, D.C., “I was just struck by how massive he really was.” Donahue coaxed Ogden across the country to be part of two Pac-10 championship teams and posting a 4-0 record against USC. As a senior, Ogden helped make a two-time 1,000-yard rusher out of Karim Abdul-Jabbar and allowed only two sacks.” Inducted into the UCLA Athletic Hall of Fame in 2006 with his number retired, and voted into the College Football Hall of Fame in 2012, Ogden was the fourth overall pick in the 1996 NFL Draft and played 12 seasons for Baltimore, starting all but one of 177 games, four times first-team All-Pro, appearing in 11 Pro Bowls, helping the Ravens win Super Bowl XXXV. That led to a 2013 Pro Football Hall of Fame entry. Which also begs the fact: His bio on ProFootballReference listed him at 6-foot-9 and 345 pounds, as did the Jonathan Ogden Foundation official website.

Not well known: Ogden won the 1996 NCAA indoor track title in the shot put as a senior, finished fourth in the 1995 NCAA outdoor championships and was fifth in both 1994 and ‘95 in the indoor championships and at one point had visions of making the U.S. Olympic team.

Jeff Bregel, USC football offensive lineman (1983 to 1986):

Best known: The 6-foot-4, 280 pound guard was a two-time consensus All-American who played in the 1985 Rose Bowl, 1985 Aloha Bowl and 1987 Citrus Bowl and was a USC captain in 1986. He was the recipient of the 1985 Pac-10 Morris Trophy as the conference’s most outstanding offensive lineman.

Not well known: Born in Redondo Beach and a standout at Kennedy High in Granada Hills, Bregel won the USC’s Football Alumni Club Award for highest grade point average in 1986. He also received the NCAA Post-Graduate Scholarship in 1986 and was named a 1986 National Football Foundation Scholar-Athlete and a 1986 Academic All-American first teamer.

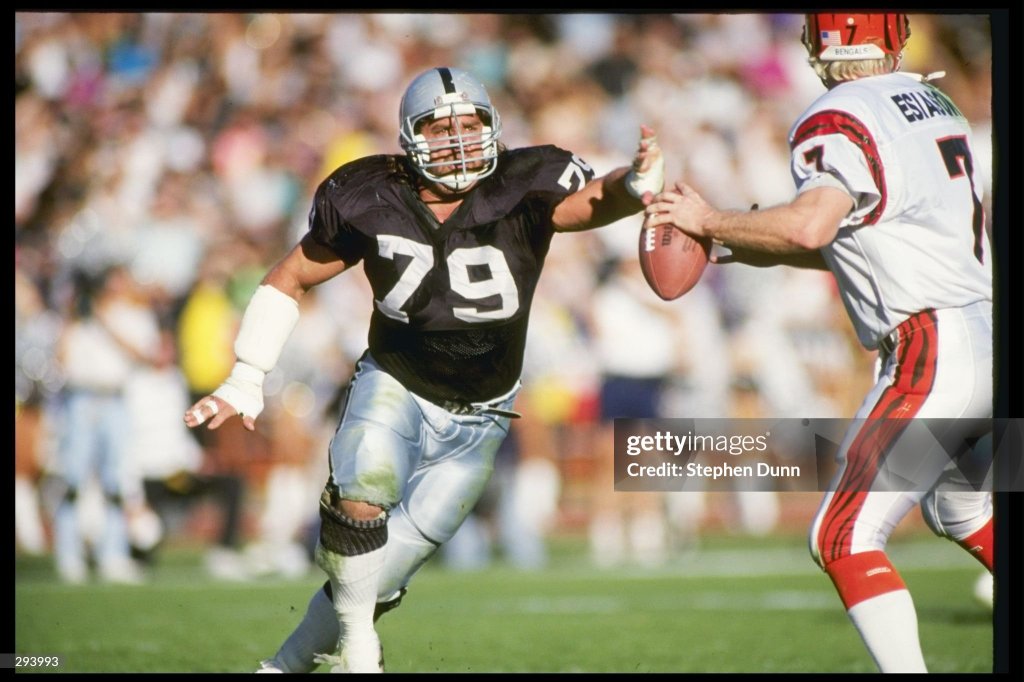

Bob Golic, Los Angeles Raiders defensive tackle (1989 to 1992):

Best known: The last four of his 14-season NFL career was in Los Angeles with the Raiders as starter through his age 35 year in ’92, after having made three Pro Bowls for Cleveland (1985 to ’87). He played in 57 games with 53 starts for the Raiders, recording 8.5 sacks and three fumble recoveries. The L.A. experience helped Golic leap into an acting career as well as work on local sports-talk radio.

Not well known: In one of Golic’s first TV roles, an episode of “Coach” in 1993 called “The Bigger They Are …,” he played former Minnesota State star Eddie Garrett who came back to the school to announce his retirement from the NFL — and reveal he had been battling cancer brought on by steroid use. It was not autobiographical as it was mostly tied to the story of how Golic’s former Raiders’ teammate, Lyle Alzado, had just been on the cover of Sports Illustrated as one of the first major U.S. sports figures to admit to using anabolic steroids, leading to a brain tumor that eventually caused his death.

Rob Havenstein, Los Angeles Rams offensive right tackle (2015 to 2025):

Best known: A four-time team captain, the 6-foot-8, 322-pounder out of Wisconsin (second round pick, No. 57 overall) started all 161 games played, including playoffs, in his 11-year career with the Rams. His 148 regular season starts are seventh in franchise history and third-most for an offensive lineman behind Hall of Famers Jackie Slater (211) and Orlando Pace (154).

Not well known: The Rams’ stat department documented that, at the time Havenstein retired after the 2025 season, he logged 9,915 total snaps and recorded three seasons with more than 1,200 snaps played (2018, 2020, 2021).

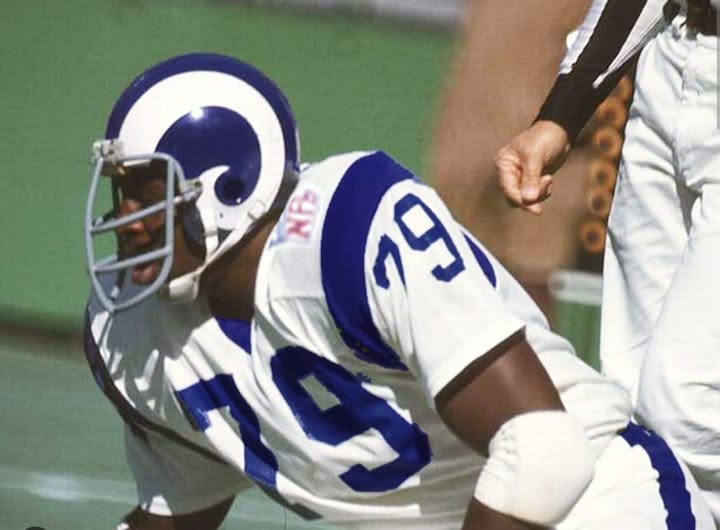

Coy Bacon, Los Angeles Rams defensive tackle/end (1968 to 1972):

Best known: Out of Jackson State, Bacon drew the attention of Rams coach George Allen, who orchestrated a trade with Dallas to get his right in exchange for a fifth-round draft pick. Bacon made it into the Rams’ starting lineup after Lamar Lundy retired and was the next generation of their “Fearsome Foursome” lineage. Bacon’s final season with the Rams in 1972 was worthy of Pro Bowl recognition, after which he moved on to play in San Diego, Cincinnati and Washington through age 39.

Not well known: His birth name was Lander McCoy Bacon.

Gary Jeter, USC football defensive tackle (1973 to 1976):

Best known: A four year starter and part of USC’s 1974 national title team, Jeter had 234 career tackles and was All-Conference first team honors his last three seasons. At USC, Jeter played in three Rose Bowls (1974-75-77) and in the 1975 Liberty Bowl.

Not well known: His 13-year NFL career included six seasons with the Los Angeles Rams (1983 to 1986) wearing No. 77.

We also have:

Sam Baker, USC football offensive tackle (2003 to 2007)

Mike Fanning, Los Angeles Rams defensive tackle (1975 to 1982)

Lance Zeno, UCLA football center (1988 to 1991)

Anyone else worth nominating?

1 thought on “No. 79: Forest Whitaker”