This is the latest post for an ongoing media project — SoCal Sports History 101: The Prime Numbers from 00 to 99 that Uniformly, Uniquely and Unapologetically Reveal The Narrative of Our Region’s Athletic Heritage. Pick a number and highlight an athlete — person, place or thing — most obviously connected to it by fame and fortune, someone who isn’t so obvious, and then take a deeper dive into the most interesting story tied to it. It’s a combination of star power, achievement, longevity, notoriety, and, above all, what makes that athlete so Southern California. Quirkiness and notoriety factor in. And it should open itself to more discussion and debate — which is what sports is best at doing.

The not-so- obvious choices for No. 59:

= Collin Ashton, USC football

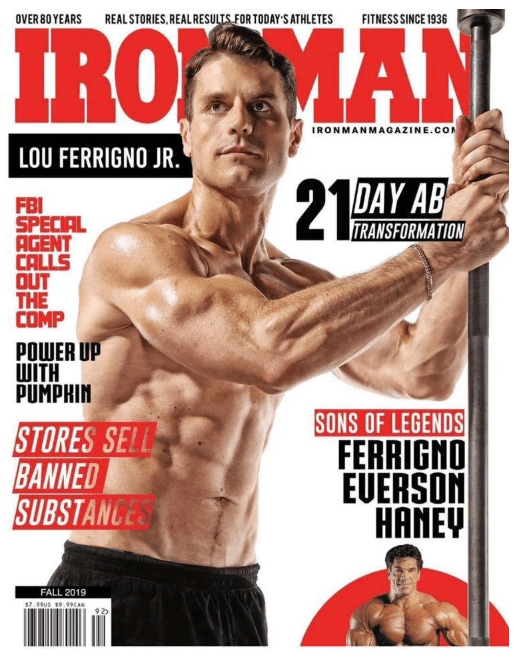

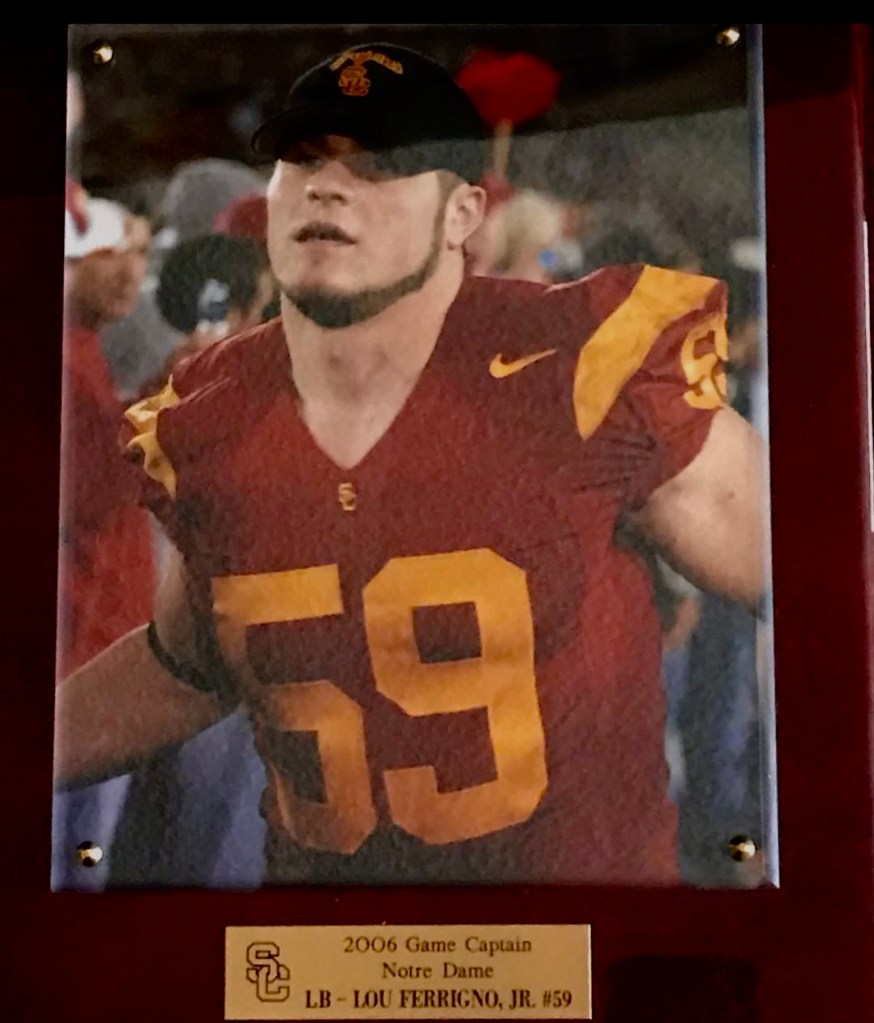

= Lou Ferrigno Jr., USC football

= Mario Celotto, USC football

= George Kase, UCLA football

= Evan Phillips, Los Angeles Dodgers

= Ismail Valdez, Los Angeles Dodgers

= Loek Van Mil, Los Angeles Angels

The most interesting story for No. 59:

=Barbie, pop culture icon (1959 to present)

Southern California map pinpoints:

Hawthorne, El Segundo, Los Angeles

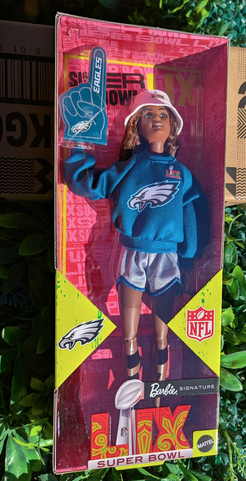

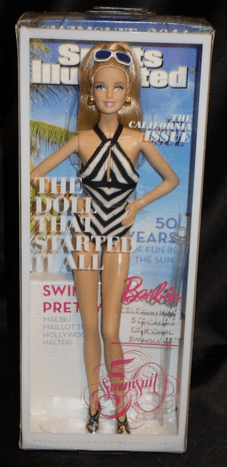

Of all the pretty people, impenetrable places and pretend things to chose from, Barbie pushed herself onto the cover of Sports Illustrated in early 2014.

It figures that the iconic figurine and model citizen created by the then-Hawthorne based Mattel toy company wasn’t depicted as an athlete. This wasn’t the SI Sportsperson of the Year issue.

Yet, jockified Barbie could play the part, and this could have passed as fashionable forward thinking here.

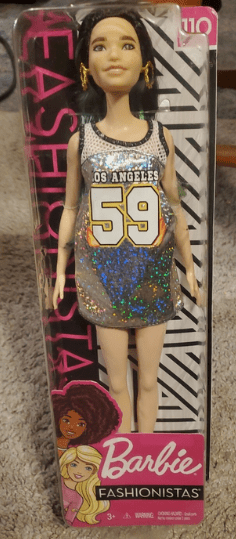

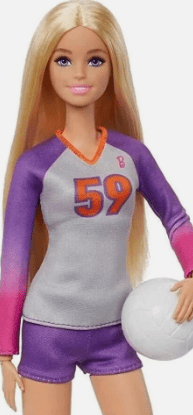

Through the years, Barbie has gone beyond a fancy-dressed glamor symbol. She’s been a volleyball player. And a soccer player. And a softball player. Name the sport — we’re even thinking pickleball — and in many display cases, she’s sporting a No. 59 jersey.

That’s a call back to the year she was created, 1959.

Some of those “59” Barbies also tout off her active lifestyle as part of the “Malibu Collection,” along with genital challenged boyfriend, Ken.

But for this purpose, for this SI cover, this Barbie, a certified Southern California 11 ½-inch titan, was on the Swimsuit issue. Wearing her a classic black-and-white one-piece retro swimsuit.

Legendary photographer Water Ioos, Jr., was also in on the photo shoot.

“She’s like the best model I’ve ever worked with,” he said. “She takes directions almost silently.”

Officially, it was an #unapologetic synergistic “cover wrap” to coincide with the American International Toy Fair, as well as celebrate the 50th anniversary of the magazine. Indeed, Mattel paid SI for the privilege of its platform exposure. And a limited edition SI Barbie doll went on sale to cash in on it all.

All in all, this Barbie/SI co-oped exposure became uncomfortable pearl clutching for some concerned about the image-consciousness messaging to young women.

“Mattel has long contended with complaints that Barbie, with her lithesome figure and focus on fashion, is not a positive role model for girls,” a New York Times story noted. “At the same time, Sports Illustrated is no favorite of some critics who believe that the swimsuit issue objectifies women.”

A Mattel spokesman responded in a story for NBC News: “Barbie has always been a lightning rod for controversy and opinions. Posing in SI gives Barbie and her fellow legends an opportunity to own who they are, celebrate what they have accomplished and show the world it is OK to be capable and captivating.”

That story noted Sports Illustrated claims to have more than 17 million women read its Swimsuit issue, more than most major fashion magazines combined, and sales for items the models wear get a significant boost.

“Barbie sort of has been taken hostage,” said a university marketing professor, “(but) despite her haters and naysayers, she’s comfortable with who she is.”

A Time magazine chimed in with: “In Defense of Barbie: Why She Might Be the Most Feminist Doll Around.” As comments ranged from outraged to supportive, it declared: “Barbie has worked every second of every day since she was invented in 1959, and she’s broken more glass ceilings than (former Facebook/Meta COO) Sheryl Sandberg. Sure, (Barbie) started off as a teen fashion model, but quickly worked her way up to fashion editor, then decided ‘what the hell’ and went back to get her doctorate in astrophysics so that she could be an astronaut by 1965. In the 1970s she performed surgeries and won the 1975 Olympics (where she dominated every event, since no other athletes competed that year). And in the ’90s she ran for President, performed with the Rockettes and played for Dallas in the WNBA.”

In the course of her controversial body of work, Barbie has assumed some 250 careers. Sports has popped in there when convenient and progressive. Just like going into the Sports Illustrated branding strategy, which came with an op-ed piece Barbie “wrote” to address what she’s all about.

“Upon the launch of this year’s 50th anniversary issue, there will again be buzz and debate over the validity of the women in the magazine, questioning if posing in it is a blow to female equality and self-image. In 2014, does any woman in the issue seriously need permission to appear there?”

The editors at the then-Refinery29.com young lifestyle brand media platform summarized:

“Barbie’s statement does gloss over the real issue at heart of more nuanced complaints against Sports Illustrated, though. Those who do take issue with the way models are presented in the magazine don’t criticize the models for posing, but rather, the magazine’s tendency to infantilize, objectify, hypersexualize, homogenize, and generally reduce women to sex symbols without much thought for their undoubtedly multifaceted personages. Barbie says that “the assumption that women of any age should only be part of who they are in order to succeed is the problem,” and that’s true, but there’s a convincing argument to be made that publications like Sports Illustrated don’t actually offer an outlet for comprehensive self-expression, much less a platform for beautiful women who don’t fit a particular mold. …

“But, the fact remains that a lot of faux-feminist criticism of Barbie, of Kate Upton, of Beyoncé, or any woman who shows skin is more based on slut-shaming than anything else, and the old stereotype that a certain type of femininity is indicative of stupidity. And, in response to that, Barbie rightfully points out: ‘Let us place no limitations on her dreams, and that includes being girly if she likes … Let her grow up not judged by how she dresses, even if it’s in heels; not dismissed for how she looks, even if she’s pretty.”

Pretty heavy stuff for what’s been called the largest multimedia-supported fashion doll franchise ever created.

In 2006, it was estimated that more than a billion Barbie dolls had been sold worldwide in over 150 countries, with Mattel claiming three Barbie dolls are sold every second.

In her book “Forever Barbie: The Unauthorized Biography of a Living Doll,” author M.G. Lord argued that Barbie is the most potent icon of American culture of the late 20th century. “She’s an archetypal female figure, she’s something upon which little girls project their idealized selves,” she writes. “For most baby boomers, she has the same iconic resonance as any female saints, although without the same religious significance.”

Writing for Journal of Popular Culture in 1977, Don Richard Cox noted that Barbie had a significant impact on social values by conveying characteristics of female independence, and with her multitude of accessories, an idealized upscale lifestyle that can be shared with affluent friends.

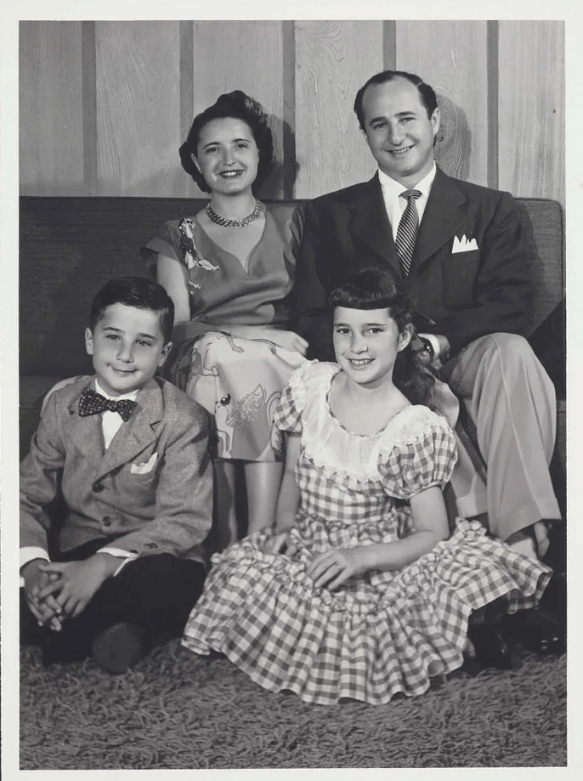

The person most responsible for Barbie image-shaping over the years had been her actual creator, Ruth Handler, who co-founded Mattel with husband Elliot in 1945. A third exec, Matt Matson, joined the Handlers as the name Mattel came from his first name and “el” from Elliot.

Rhea Perlman played Handler in somewhat of a spiritual guide in the 2023 Warner Bros.-released, Greta Gerwig-directed, quirky, satirist eye-opening “Barbie” movie in 2023.

Handler’s daughter, Barbara, liked to play dress-up with her paper dolls of adult women. The Barbie doll, named for her, happened with Barbara was a 16-year-old at Hamilton High School in the Beverlywood area of L.A.

In a 1989 interview with the Los Angeles Times, Barbara Handler Segal said she was nothing like the Barbie doll when she was a teenager.

“If the doll is like me, it is totally coincidental,” said Segal, then 47 and a divorced mother of two who golfed at Riviera Country Club and played tennis.

Segal said the Barbie doll never was part of her own daughter’s life at their Brentwood home.

According to the Mattel narrative, the doll’s official name is Barbara Millicent Roberts. She was supposed to mimic the glamor of the 1950s movie stars.

Ken, Barbie’s boyfriend, was named after Handler’s son, Ken, who arrived the year he was born in 1961. Ken Handler, who also went to Hamilton High, became a New York City real estate investor. He said in high school, he “played the piano and went to movies with subtitles … I was a nerd — a real nerd. All the girls thought I was a jerk.” His kids never played with Barbie or Ken dolls. Ken Handler died at age 50 in 1994.

Sports and Barbie have intersected in all sorts of ways.

Her first depiction of a tennis player came in 1962. She donned a soccer uniform for the first time in 1998, ahead of the Women’s World Cup in Los Angeles in 1999.

As a baseball player player, she came out in 1993 and was MLB specific in versions of teams in 1998. A softball version came as part of the 2020 Olympics collection. As a volleyball player, she was there in 2023.

During International Women’s Day in March 2018, Mattel unveiled the “Barbie Celebrates Role Models” campaign with a line of 17 dolls, informally known as “sheroes,” that included snowboarder Chloe Kim, boxer Nicola Adams, Olympic fencer Ibtihaj Muhammad, soccer player Sara Gama, and gymnast Gabby Douglas. Two years later, the series added Paralympic wheelchair racer Madison de Rozario and fencing champion Olga Kharlan.

In July 2021, Mattel released a Naomi Osaka Barbie doll to honor the women’s tennis star as a part of the ‘Barbie Role Model’ series. Osaka originally partnered with Barbie two years earlier.

For the 2024 Summer Olympics in Paris, a new line of Barbie dolls honoring female athletes emerged called “Team Barbie,” modeled after actual athletes.

In early 2026, the Los Angeles Times’ story under the headline “Why Mattel now has a problem with Barbie” focused on how the company’s shares plunged 25 percent when it was announced that holiday-season sales were weak and that it expects another slow year. It said the doll and its many variants had been “losing momentum since her latest 15 minutes in the spotlight” following the 2023 movie “Barbie.” Despite efforts to create buzz around the Barbie brand — including a diabetes Barbie and an autism Barbie — gross billings for Barbie products slid 11 percent in ’25, following a similar decline in ’24.

For what it’s worth, Mattel estimates there are more than 100,000 avid Barbie collectors, with 90 percent of them women in the 40-year-old range, who buy about 20 a year. About half of those spend about $1,000 a year on their collection.

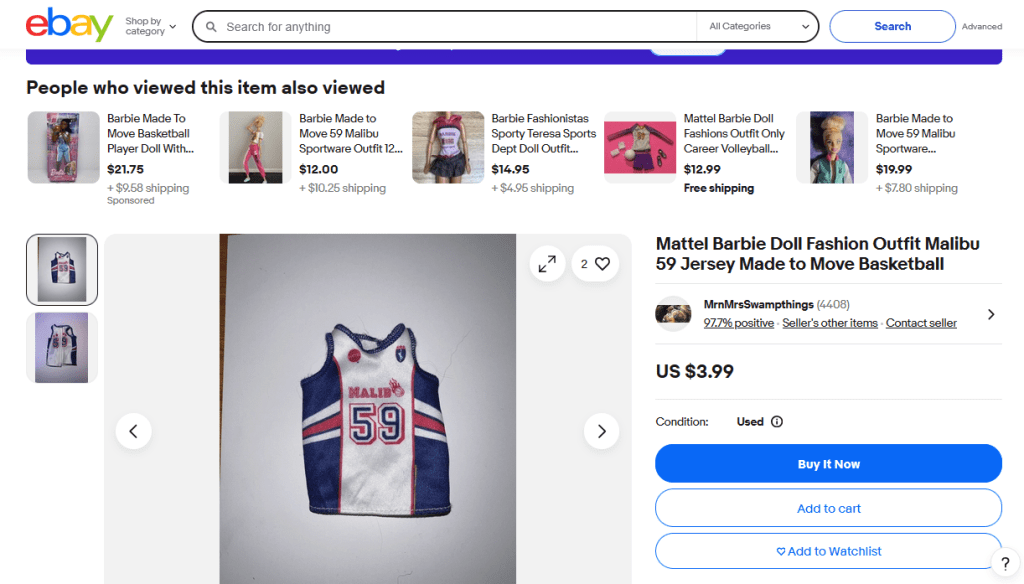

And if you’re still on the search for that 2014 SI collectable cover girl, we’ve located a few on eBay. Many aren’t that far north of $59.

Who else wore No. 59 in SoCal sports history? Make a case for:

Ismail Valdez, Los Angeles Dodgers pitcher (1994 to 2000), Anaheim Angels pitcher (2001):

Best known: A year after he won 13 games and posted a 3.05 ERA with two shutouts as a rookie in 1995, Valdez followed it with a 15-7 mark and 3.22 ERA in 33 starts at age 22. Yet in his seven MLB season career, including one back in L.A. after he was traded to the Chicago Cubs, Valdez shows just a 61-57 record and 3.48 ERA. He signed with the Anaheim Angels as a free agent in 2001.

Not best remembered: Valdez’ most headline-worthy incident was in April of 1997 when he got into a shower-area altercation with teammate Eric Karros, who openly ridiculed Valdez in a team meeting for lasting just 3 1/3 innings, allowing eight hits and four runs in his worst start in two years.

Evan Phillips, Los Angeles Dodgers pitcher (2021 to present):

Best known: Picked up off waivers from Tampa Bay in August of 2021, Phillips had a 3-0 record and 0.00 ERA in 12 games covering five post-season series from ’21 to a World Series title in ’24. That included 21 strike outs in 15 1/3 innings. He struck out six of the 12 batters he faced in the ’21 NLCS versus Atlanta over three innings and fanned six of the 11 in the ’22 NLDS against San Diego. In five regular seasons with the Dodgers, Phillips compiled a 15-9 record with 45 saves in 78 games finished, a 2.22 ERA in 201 innings, with 221 strike outs over 195 innings (10.2 SO9 and 4.25 SO/BB ratio) for a 4.1 WAR. It has led to one of his nicknames listed on Baseball-Reference.com as “High Leverage Honey Bun.” Coming off Tommy John surgery, after appearing in just seven games in 2025 and getting one save, Phillips signed a one-year, $6.5 million deal for the 2026 season, even thought he won’t be ready to play until July.

George Kase, UCLA football defensive tackle (1991 to 1995):

Best known: A starter at nose guard as a sophomore and junior, the 6-foot-3, 250-pounder out of Hart High in Santa Clarita was moved to defensive tackle when UCLA went to a four-man front. He led the team in tackles for losses and sacks as a senior. He finished with 137 career tackles, 90 solo and 11 sacks. A three-time Academic All-American, he married USC swimming and diving coach Catherine Vogt in 2018.

Not well remembered: Kase is one of only 19 players in the history of the UCLA-USC game to win five years in a row against his rival.

Have you heard this story:

Collin Ashton, USC football linebacker (2002 to 2005)

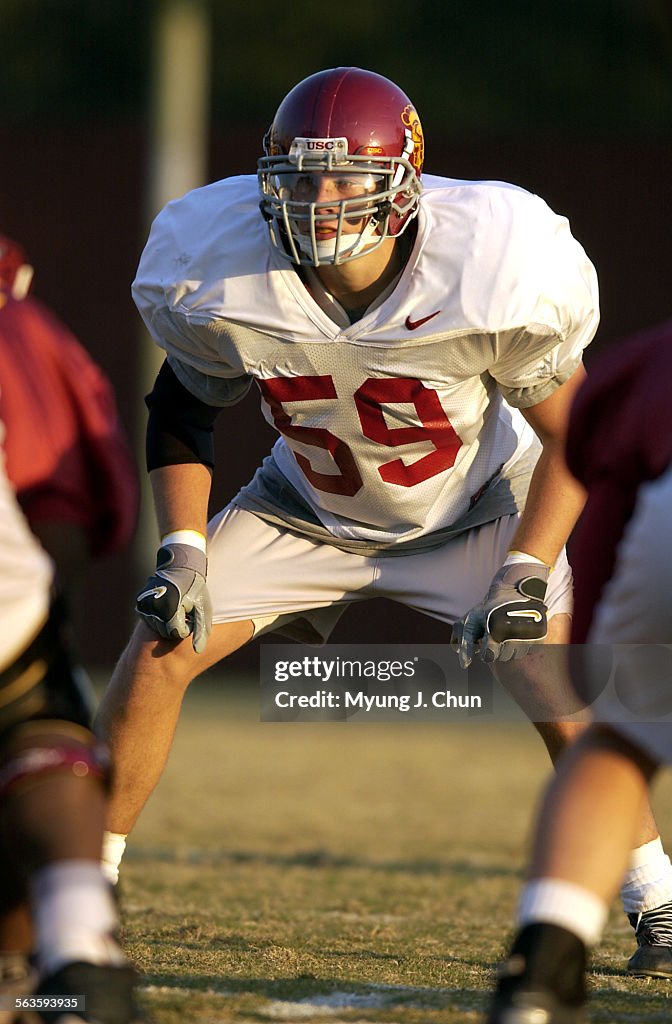

Lou Ferrigno Jr., USC football linebacker (2006 to 2007)

During the USC heydays of the Pete Carroll Era, when having a spot on the roster a was as much a ticket to a carnival ride, two No. 59s had different experiences as walk-on linebackers for the Trojan football program.

Ashton, who as a kid growing up in Mission Viejo never missed a Trojans football since the day he was born, and had four generations before him attend the school, was just hoping he could be used a long-snapper when he approached Carrol for a tryout. Ashton ended up starting a few games at linebacker as a senior because they needed healthy bodies. All the way to a national title game.

Ferrigno Jr., the son of a Hollywood star/acclaimed body builder, knew his DNA alone wouldn’t be enough to get him a shot. He played in high school and got attention. He asked Carroll for a shot. He tried, he got injured. He begrudgingly got into acting. He made a career out of that.

If a walk-on can act if he/she belongs, that’s half the battle. It could lead to a script for the next “Rudy.”

When Ashton was introduced with the rest of the USC senior class prior to the No. 1 Trojans’ game at the Coliseum against No. 11 UCLA in 2005, he couldn’t have imagined it would be as a member of the starting lineup. Ashton had attended and/or participated in every USC football game at the Coliseum since he was a two-month old in 1983. His father, grandfather, great-grandfather and great-great-great grandfather attended USC as well.

“I was brought up in a family where ‘SC is awesome and some other school is not,” he told the San Bernardino Sun. “I just kinda followed tradition, kept it going. The five generations thing didn’t really come up much.”

Mark Ashton, Collin’s dad, told the Orange County Register’s Mark Whicker in September of 2005 that the commitment was there to attend any USC home game that it took some innovation.

“He’d play a Pop Warner game in La Habra or somewhere on a Saturday morning and there’s no way we could get back home to Mission Viejo and still make the game.

So we’d pack these warm-water jugs, and open up the car doors and he’d get behind them and take off his uniform, and we’d basically wash him off right there. Then we’d go to the Coliseum.”

Ashton and his two twin younger brothers already worked their way into being ballboys at the USC basketball games when George Raveling was the head coach.

At Mission Viejo High, Ashton was a reliable long-snapper. Coach Bob Johnson alerted his USC contacts that Ashton could be worth checking out. Assistant coach Kenny Pola came to a Diablos’ practice to see for himself. It was worth the trip.

Beginning as a redshirt freshman in 2001 when Carroll first arrived, Ashton started his routine to suit up by putting on the same gray USC T-shirt that he first had as a 10-year-old.

“A lot of people didn’t think I could do it — a lot of them laughed at me and said I was wasting my time,” Ashton said about deciding to be a walk-on. “I’m not dumb. I looked out on the field in my first few weeks here and I could see everyone was bigger, stronger and faster than me. I knew it would be tough before I got here, but it was even worse than I thought.

“Every Saturday would come and I’d never get close to playing. But I knew why. If I was the coach, I wouldn’t have played me, either … Sometimes I would think, ‘I cannot do this for five years, no way.’… My whole goal was to win a scholarship here, to work my way up. So I kept working.”

As a walk-on, Ashton realized he couldn’t get into the weight room for training like some of his other teammates.

“I got really angry one time,” he said. “We had lifting sessions at 6, 8 and 10 a.m. I was only allowed to go at 6 and 8. I didn’t get up for the 6 and I had class at 8. So I show up for the 10 and they say no. That was tough. Little things like not being able to get a protein shake when you need to. Then again, it’s supposed to be tough. If you don’t love the game you’re not going to make those sacrifices.”

In 2002, he got into three games and made three tackles. As a sophomore in 2003, starting third on the depth chart at weak-side linebacker behind Melvin Simmons, Matt Grootegoed and Oscar Lua and Lofa Tatupu, Ashton played in all 13 games as USC went 12-1 and won the Rose Bowl. He piled up 28 tackles and forced a fumble as a backup linebacker and on special teams.

When he started in the Trojans’ 47-22 win over UCLA at the Coliseum, he became the second USC walk-on to start a game in the previous 20 years.

As a junior in 2004, Carroll gave Ashton a full scholarship as a long snapper on punts and backup middle linebacker.

“That’s my favorite thing to do here, give out scholarships like that, and it shows you how special Collin is when his teammates gave him a standing ovation,” Carroll said. “He came here undersized and not prepared for football at this level, but he did not believe that.”

“From what coach Carroll instills, being a Trojan is being someone who is always ready to compete,” Ashton said. “Someone who will do anything to be competitive.”

Ashton got into all 13 games as a junior, making 16 tackles. USC went 13-0 and won the national title against Oklahoma in the Orange Bowl.

“The story is crazy, man,” USC tight end Alex Holmes said of Ashton prior to the Orange Bowl. “I mean, really crazy.”

As a senior in 2005, with a USC linebacking crew that included Lua, Dallas Sartz and Keith Rivers, the Trojans went 12-0 into the 2006 Rose Bowl before losing the national title game to Texas. Ashton had ended up starting at all three linebacker positions because of injuries to teammates. He was third on the team in tackles with 54, had an interception and broke up two passes.

After the USC-Texas national title game, the 22-year-old Ashton retired his gray USC T-shirt.

“When you hold is up you can see right through it,” he said. “It really wasn’t a good-luck thing. It was just a routine. My dad wants it for some reason. He wanted to do something with it. I don’t really care.”

After playing in the Hula Bowl, Ashton got a look at by the San Diego Chargers but was released in May of 2006. Same with the Baltimore Ravens. But in 2007, he was a middle linebacker for the Flash de la Courneuve in Paris, France. The team won its Ligue Élite de Football Américain title. Ashton became the chief operating officer for a high-end property management company.

“(The former USC player) brings the same drive and determination from the field to the world of property management,” according to his website bio.

In October of 2006, a sports blog called “The Church of Albert” devoted to Florida Gators sports threw out the click-bait question: If your favorite college football team was a super hero, what would it be?

Mike Penner of the Los Angeles Times found it interesting and ran with it. He noted that Wolverine, appropriately, was assigned to the University of Michigan. Superman was given to Notre Dame.

For USC, it assigned the Incredible Hulk.

“(Hulk) is an unstoppable force of nature that you do not want to get angry,” the site explained. “He sometimes turns into a meek little man that gets pushed around for awhile but eventually the Hulk bursts out and separates arms from shoulders. USC often puts forward meek-science-type efforts for three quarters, followed by a city-destroying fourth quarter that puts opponents away.”

It didn’t hurt at all that on the USC roster, Lou Ferrigno Jr., was waiting for his chance to burst onto the scene.

Lou Ferrigno Jr., who assumed No. 59 by Carroll after Ashton departed following the ’05 season, was a 6-foot-1, 230 pounder living in Santa Monica with his famous parents when he started at Loyola High in L.A.

He graduated from Notre Dame High in Sherman Oaks in 2002 and then went to Pima Community College in Tuscon, Ariz., before finding himself on the USC campus in ‘05.

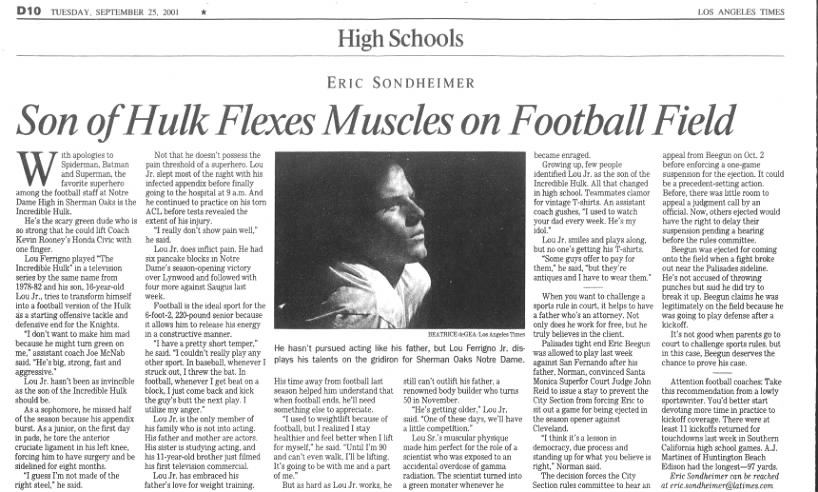

During his time at Notre Dame High, a story in the Los Angeles Times gave up any thoughts he could stay under the radar. “Lou Ferrigno played ‘The Incredible Hulk’ in a television series by the same name from 1978-82, and his son, 16-year-old Lou Jr., tries to transform himself into a football version of the Hulk as a starting offensive tackle and defensive end for the Knights,” the story read.

Lou Jr.’s story included missing time as a sophomore because of a burst appendix and tearing the anterior cruciate ligament in his left knee as a junior.

“I guess I’m not made of the right steel,” he said. “I have a short temper. I couldn’t really play any other sport. In baseball, whenever I struck out, I threw the bat. In football, whenever I get beat on a block, I just come back and kick the guy’s butt the next play. I utilize my anger.”

On USC’s 2006 depth chart for the season opener, Keith Rivers, Rey Maualuga, Oscar Lua, Dallas Sartz, Brian Cushing and Kaluka Maiava were all listed for the linebacker position. The Los Angeles Times mentioned Ferrigno Jr. on the roster, but it was noted that he suffered a knee injury on the final play of spring practice in late March, 2006, was to have a knee surgery in April, and could be ready for the ’06 opener.

That didn’t really happen. He never played a down. Ferrigno’s time in the USC program, however, includes a time when Carroll allowed him to suit up and be one of the team captains before the Nov. 25 game against 10-1 Notre Dame at the Coliseum, which resulted in a 44-24 win.

The 2006 USC team was ranked No. 2 when it sustained a 13-9 loss at the Rose Bowl against the 6-5 UCLA team to knock itself out of the Bowl Champion Series title game. A 32-18 win over Michigan in the 2007 Rose Bowl left the Trojans ranked No. 4 overall at 11-2. And it gave Ferrigno a chance to say he was on a Rose Bowl title team.

Ferrigno Jr. got a degree in communications and a minor in business law by 2007. That’s when he diverted to acting, including improv comedy training.

After a few roles, Ferrigno Jr. was noticed in role as a firefighter Tommy Kinard in the TV series, “9-1-1.”

There is one other random connection with Ferrigno Jr., and USC, that recently surfaced.

Owen Hanson, a walk-on tight end himself out of Redondo High for a Carroll team in 2004, built a business called O-Dog Enterprises. He was arrested in Australia in 2015 on federal charges of gambling and drug trafficking, pleaded guilty and, in ‘17 was handed a 21-year prison sentence, and then tried to glamorize it all with a 2024 book, “The California Kid: From USC Golden Boy to International Drug Kingpin.”

In one part of the book, Hanson wrote:

“Maybe I needed a whole shitload of cash for a large shipment of cocaine that came dirt-cheap because the original buyers had gotten arrested in a sting and my people now had to move the product fast: I could ask for a one-month loan with 20 percent interest from Lou Ferrigno Jr., the movie star’s kid who would front it to me no questions asked. Of course, I’d make thirty grand off that loan in about a week.”

The Hanson bio is part of our post for No. 88. It’s not the blue print you’d want to present to anyone who had thoughts of walking on to any college sports team program.

Mario Celotto, USC football linebacker (1974 to 1977):

Born in L.A. and raised in Rancho Palos Verdes and out of St. Bernard High in Playa del Rey, Celotto was a 6-foot-3, 228-pound linebacker who got his moment in the spotlight for USC in the 1977 annual game against Notre Dame at South Bend, Ind. Early in the second quarter with Notre Dame pushed back to its own 4 yard line, Celotto grabbed a fumble in the air by Irish tailback Terry Eurick and ran it in five yards for a touchdown, the first points by USC in the contest, tying the game at 7-7. Douglas Looney described it in his Sports Illustrated account: Sure enough, with 10:44 to play in the half, Notre Dame’s Terry Eurick was popped hard on his own five, the ball squirted loose and USC Linebacker Mario Celotto grabbed it and took three steps into the end zone. The kick tied the score, and the feeling was in the air that No. 5-ranked USC was getting ready to demonstrate why it was No. 1 before losing to Alabama—and why it might well belong back at the top of the heap. But this was best known as the contest when Notre Dame head coach Dan Devine had the team come out to play in green uniforms and, ranked No. 11 behind Joe Montana, a third-string quarterback earlier in the fall, made a statement in crushing the Trojans, 49-19. A seventh-round pick by Buffalo in 1978, he was on Oakland’s Super Bowl XV team, and finished his career with the 1981 Los Angeles Rams (wearing No. 41). After retiring, he started the Humboldt Brewing Company.

Loek Van Mil, Los Angeles Angels relief pitcher (2011):

At 7-foot-1, the Netherlands-born Van Mil was one of the tallest pitchers in professional baseball history. Some say he was the tallest. Tough to find anyone who could top that. After pitching his first four seasons in the Minnesota Twins organization, Van Mil came to the Angels in 2011 as the “player to be named later” in a deal involving reliever Brian Fuentes. Van Mil was invited to spring training, wearing No. 59, and made just one appearance before he was sent to Double-A Arkansas (where the 26-year-old was a teammate of 19-year-old Mike Trout). He started the 2012 season with the Angels’ Triple-A Salt Lake team before he was traded to Cleveland. Van Mil would pitch in Japan, for the Netherlands during the World Baseball Classic, and also in Australia. He suffered an odd death in 2019 at age 34, a year after after slipping, falling and hitting his head on rocks while bushwalking in Australia.

We also have:

Guillermo Mota, Los Angeles Dodgers pitcher (2002-to-’04, 2009)

Dan Dufour, UCLA football center (1980 to 1982)

Chuck Finley, California Angels pitcher (1986) Changed to No. 31 for the next 14 years of his Angels career.

Anyone else worth nominating?

1 thought on “No. 59: Barbie”