This is the latest post for an ongoing media project — SoCal Sports History 101: The Prime Numbers from 00 to 99 that Uniformly, Uniquely and Unapologetically Reveal The Narrative of Our Region’s Athletic Heritage. Pick a number and highlight an athlete — person, place or thing — most obviously connected to it by fame and fortune, someone who isn’t so obvious, and then take a deeper dive into the most interesting story tied to it. It’s a combination of star power, achievement, longevity, notoriety, and, above all, what makes that athlete so Southern California. Quirkiness and notoriety factor in. And it should open itself to more discussion and debate — which is what sports is best at doing.

The most obvious choices for No. 23:

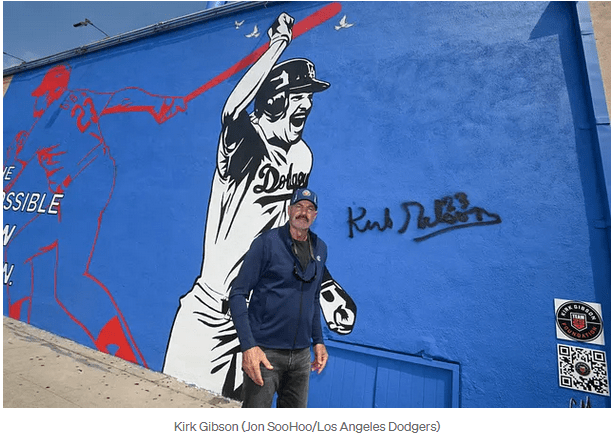

= Kirk Gibson: Los Angeles Dodgers

= LeBron James: Los Angeles Lakers

= David Beckham: Los Angeles Galaxy

= Eric Karros: Los Angeles Dodgers

= Dustin Brown: Los Angeles Kings

The not-so obvious choices for No. 23:

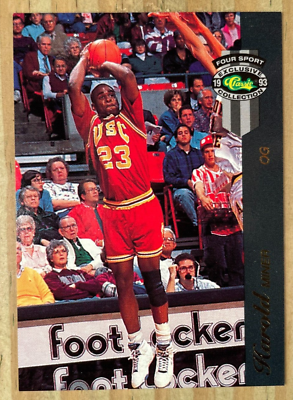

= Harold Minor: USC basketball

= Diana Taurasi: Don Lugo High School girls basketball

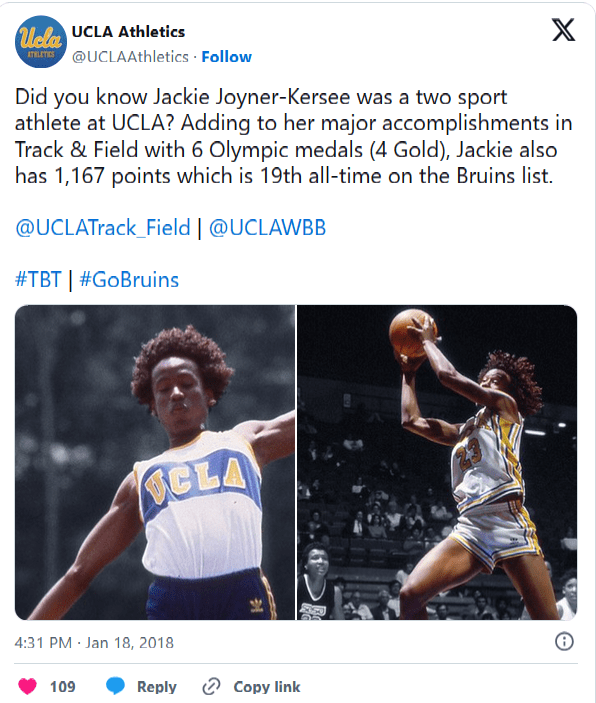

= Jackie Joyner: UCLA women’s basketball

= Jonathan Franklin: UCLA football

= Kenny Washington: UCLA basketball

The most interesting story for No. 23:

Ryan Elmquist, Caltech basketball guard (2007-08 to 2010-11)

Southern California map pinpoints:

Pasadena, Whittier, Pomona, LaVerne

Ryan Elmquist scored 36 on his ACT college entrance exam, which surely impressed his classmates at Woodbury High in Minnesota, just East of the Twin Cities.

It was a perfect score. It also gave him a ticket to dig out of the Midwest snow, head to Pasadena and enroll in California Institute of Technology — better known to “The Big Bang Theory” fandom as Caltech — to study computer science.

And play basketball.

Around Caltech, Elmquist is far better remembered when he scored one not-so-lousy free throw on February 22, 2011.

The last of his 23 points came with 3.3 seconds left, accounting for the final margin in a 46-45 for the Beavers over visiting Occidental College on their home Braun Athletic Center

It not only impressed his smarter-than-smart peers, but most of its Nobel Laureate-rich staff. It was the perfect ending to his senior season. It was the last game he played. And it ended Caltech’s streak of 310 consecutive losses in Southern California Intercollegiate Athletic Conference (SCIAC) competition. A streak started before Elmquist and his teammates were born, in January of 1985.

But who’s counting. Unless you are a campus full of math nerds.

Bazinga.

An NCAA Division III school that doesn’t give out athletic scholarships, has a modest $1.1 million athletic budget and has just 2,200 of the smartest kids in the country enrolled, Caltech did something mindblowing in a general non-scientific sense.

It took that streak ending to get mention on not only every sports network, but it wast on the CBS Evening News with Katie Couric and the ABC World News with Diane Sawyer.

“Probably for the first time in Caltech’s illustrious history of Nobel Prizes and brilliant students and faculty, there was a press conference in the gym,” the school’s official website noted in a post headlined “A (freethrow) shot heard around the sports world.“

To note: Caltech, finishing 1-13 in conference and 5-20 overall, still hadn’t had a winning season since 1954. But it was a moment that mattered.

“I feel like I just won an NCAA championship,” said Caltech coach Oliver Eslinger, who has a Ph.D. in Education and Counseling Psychology and head of the men’s hoops program since 2008, the year after Elmquist enrolled. “I’m so proud of Ryan Elmquist.”

As Elmquist told the CBS Evening News: “I can’t think of a better storybook ending.”

The 6-foot-5 forward ended up as Caltech’s leading scorer that season — a 15.8 point-per-game average might not be as sparlking as a 4.0 grade point average, but you do the math.

It was quirky enough that most of his scoring abilities were a result of his free-throw accuracy. He held the school record for most free throws made and attempted — 17 of 19 — in one game as well as those made and attempted — 414 of 660 — in a career.

In that win over Oxy, 15 points came at the line with 19 tries. He also had nine rebounds and four blocked shots.

Eureka. And such a relief.

Caltech players may know they’re not athletically the ones pro scouts come calling on, but it doesn’t mean they have to be targets of insults, especially from opponents. One time when Caltech was a visiting team, someone came into its locker room, wiped off all the Xs and Os the coach had put up for their offensive plays, and replaced it with math problems to solve. Just to taunt them.

“Of course we could solve the problem, but we never did,” said Elmhurst. “We wiped it right off and tried to focus on the game.”

Before he graduated early and headed north to start a job with Google, Elmquist put his name in the Caltech books second all-time in scoring with 1,254, first in blocked shots with 157, and the only player with 1,000 career points and 500 rebounds.

A three-year captain, three-time team MVP and CoSida Academic All-American first-teamer, Elmquist eventually was a 2024 entry into the Caltech Hall of Honor. Which honors athletes, really. It could be called an Athletic Hall of Fame. But why confuse it?

It has its own separate ongoing list of Nobel Laureates, MacArthur Fellows, National Medal of Science Recipients and National Medal of Technology and Innovation Recipients. No apparent mention of Professor Proton, however.

Aside from his career stats, Elmquist’s honor was a reflection of the free throw that secured Caltech’s five-win season, the most it had collected against NCAA opponents in 50 years.

Google all that when you get a chance.

The sports heritage

Numbers matter at Caltech.

The men’s basketball team, one of 16 divisible varsity programs on the campus, rallies behind the workmanship of mascot Bernoulli Beaver (or Berni for short, officially named in 2023 by a vote to pay homage to the Bernoulli family of 18th Century mathematicians).

The Beaver nickname also acknowledges a species known as “nature’s engineers.” (Look it up: The Massachusetts Institute of Technology also has the beaver as its mascot, for the same exact reason. Its beaver is named Tim. Maybe because it’s “MIT” spelled backward).

With its orange-and-white color scheme, Caltech seems to create an illusion that this is a Southern branch of Oregon State University. Leave it to the Beavers to be willing to take on the roll as cannon fodder for more athletic-savvy schools of higher learning.

While Caltech fielded an actual football team for 100 years — once defeating USC in 1896 — its most glorious moments in or near a gridiron involve two well-remembered Rose Bowl pranks. The school even documents them for posterity on its website.

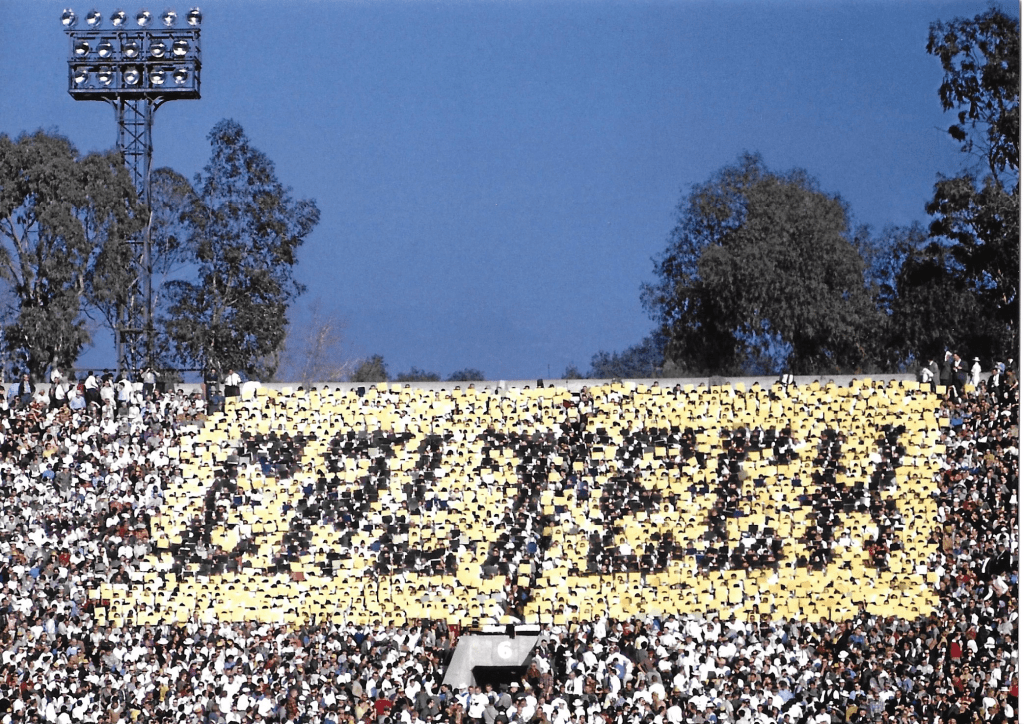

On Jan. 2, 1961, in what became known as “The Great Rose Bowl Hoax,” a small band of ingenious students surreptitiously altered a University of Washington halftime flip-card routine so that it showed the Caltech Beavers mascot and then spelled out “CALTECH” instead of what Washington planned to be an American flag.” NBC broadcasters Mel Allen and Chick Hearn broke out in laughter on the air when the stunt occurred. It involved changing the 2,400 cards kept in the Huskies’ cheerleader dorm on the Long Beach State campus.

On Jan. 2, 1984, during the UCLA-Illinois Rose Bowl, Caltech students were able to sabotage the scoreboard and display: “Caltech 38, MIT 9” in the third quarter. Two students were charged with misdemeanors, admitting they spliced a remote-controlled computer and other electronic gadgets into the wiring of the scoreboard.

(Do you notice the dependency of a Jan. 2 Rose Bowl date may be cause to send Caltech students offkilter?)

When the then-known Throop Institute created a football program 1893, two years after the opening of what would eventually be California School of Technology, its record-keepers duly noted that it suffered 60-0 loss against USC. In 1896, Caltech defeated USC, 22-0, for the program’s first recorded victory.

It won the SCIAC titles in 1930 (5-3-1) and ’31 (6-2-1), actually playing some of its home games at the nearby and vastly oversized Rose Bowl. It stopped competing in the SCIAC in 1968 (after a 1-7 season)and moved to becoming a JV, a club and a school recreation sport until it was retired in 1993 with a cumulative record of 179-371-18. Officially, its final game of 1993 was a 32-13 loss to the Hawthorne Cougars.

Because our own brain can’t always tackle this kind of subject matter, we asked Google AI if it could generate a list of the greatest athletes in Caltech sports history. That seemed an appropriate method of attack.

This is what it spit out:

The choice of the “greatest” often depends on whether one values single-sport dominance or multi-sport versatility. Determining the single “greatest” athlete is subjective, but several standout individuals are recognized in the Caltech Athletics Hall of Honor (established in 2014) for their exceptional dominance and records. Notable candidates include:

Sarah Wright, Class of 2013: She competed on the men’s soccer team (Caltech did not have a women’s team at the time, but eventually did) as well as the women’s basketball team and the track & field team. She still holds the school record in the heptathlon and ranks in the top ten in numerous other track and field events. Her trailblazing role in women’s sports at Caltech is also a significant part of her legacy. (Inducted in 2023) (Note: In 2012, she founded a non-profit called Engineers Beyond Borders Caltech chapter)

Steven Sheffield, Class of 1972: A dominant force in the pool who was a multi-sport athlete in men’s water polo and swim & dive, he set multiple program records across several swimming events and earned All-SCIAC honors in both sports. (Inducted in 2023)

Jim Hamrick, Class of 1986: All-SCIAC honors during the four years he played baseball, setting single-season and career program records for home runs and RBIs. (Inducted in 2016).

Nice, but … the AI search, however, wasn’t all that inclusive. It passed over these gems easy to find in the Hall of Honor:

Grant Venerable, Class of 1932: The San Bernardino High grad went to USC, Cal Berkeley and UCLA (some eight years before Jackie Robinson did) before transferring to Caltech as its first Black graduate. He spent two years on the school’s track and field team. (Inducted in 2020).

Fred Newman, Class of 1959: All-SCIA in baseball, basketball, football and soccer, he also set a Guinness Book of World Records mark in basketball shooting ability — making 20,371 free throws out of 22,049 attempts in a 24-hour period from Sept. 29-30 in 1990. At age 60, he also made 88 straight free throws while blindfolded and 209 straight 3-point shots. Field of expertise: Computer programming. (Inaugural class of 2014).

Glenn Graham, Class of 1926: Captain of the school’s track team, he won the silver medal in the pole vault at the 1924 Olympic Games in Paris, clearing 3.95 meters, and losing in a jump-off to American Lee Barnes. (Inaugural class of 2014).

The 1953-54 Men’s Basketball team: Winners of the first outright conference title in program history, taking the SCIAC with a 6-2 record. (Inducted in 2016).

And, there’s also Elmquist.

The streak

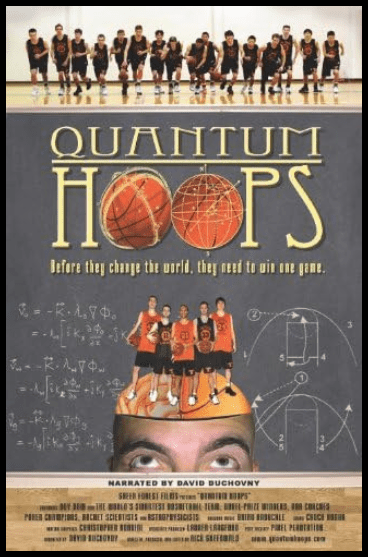

In 2007, the year Elmquist entered Caltech, a rather shallow documentary dropped called“Quantum Hoops.” The tagline: “Before they change the world, they need to win ONE game.” Ben Stiller was given the project by Disney to make it into a feature film which still apparently is on the grease board.

The doc jumped into following the basketball team amidst its then-21-year losing streak as the 2006 season winded down. At that point in time, Caltech had a 60-game overall losing streak and hadn’t won a Division III game in 11 years.

The New York Times was rather dismissive of the doc, calling it “just the cutest thing” under the headline: “This Is Basketball, Boys; It’s Not Rocket Science.”

The film’s all-over-the-place presentation — more on the Caltech history than its hoops — pointed out the school could claim the highest ratio of Nobel Prize winners to faculty and a men’s basketball team to losses. About 35 percent of the Caltech graduates go on to earn a Ph.D, and 25 percent of the students arrived this fall with SAT scores of 2,330 (out of 2,400) or better.

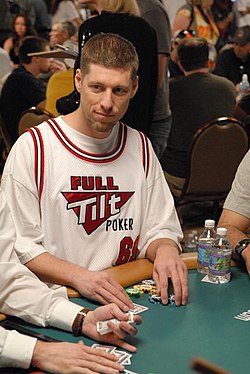

It also once had a player named Huckleberry Seed, a 6-foot-7 center who dropped out in his sophomore year to become a professional gambler and went on to win World Series of Poker. While basketball is excellent, playing poker in your pajamas has its perks.

It also featured San Antonio Spurs’ Hall of Fame-bound coach Gregg Popovich, who had a Pomona-Pitzer team that once lost to Caltech and then later rebounded to win the SCIAC conference.

Peter Roby, director of Northeastern University’s Center for the Study of Sport in Society, had said in the Christian Science Monitor in 2007: “It is a tribute to their unwillingness to compromise their [academic] standards that they have endured for as long as they have.”

In January of 2007, after the film’s release, Caltech snapped its 207-game losing streak to D-III schools when it outlasted Bard College, a private liberal arts school in Annandale-on-Hudson in New York, 81-52.

But it wasn’t until the win over Occidental in 2011 that Caltech could claim its first SCIAC win as it went up against the likes of Cal Lutheran, Claremont-Mudd-Scripps, Redlands, Whittier, La Verne and Chapman over more than a half century.

The men’s hoops team was hardly alone in carrying out losses to the nth-degree in that time period.

The women’s team lost 50 in a row until it won its first SCIAC game, also in January of 2007, defeating Pomona-Pitzger’s Sagehens. The school’s baseball team had lost 412 consecutive conference games since 1988, and 170 consecutive games over all, dating to 2003. The streak would end in 2013.

The Los Angeles Times’ Bill Plaschke had been keeping tabs on the Caltech basketball story back to the 20th Century. At that point, in 1997, the Beavers had a 12-year, 110-game D-III losing streak. They almost broke that but fell to Occidental, 44-40, in January of ’97.

Plaschke started a piece with a quip about how Beavers guard Josh Moats was about to throw an inbounds pass in a game against Cal Lutheran, and someone from the stands yelled: “Shouldn’t you be home doing your homework?”

To which Moats said later: “I was thinking: ‘You know, that guy was right’.”

Caltech once considered dropping out of the SCIAC, where it was a founding member in 1915. For four years in the mid-1980s, it even dropped varsity basketball entirely. The students eventually wouldn’t allow it to be.

When the 2010-11 basketball season for the men and women started with its Oct. 16 “Midnight Madness” celebration for the first official day students could practice in the Braun Gym, Plaschke was back noted that there was a pep band riling up the crowd of about 500 with one cheerleader.

“Pep band?” asked Elmquist. “Since when do we have a pep band.”

Since three days ago, Plaschke wrote.

For the students, a half-court shooting contest took place where the winner received an autographed basketball with the signatures of five Nobel Prize winners who teach at Caltech.

The men’s team started the ’10-’11 season on a predictable trajectory. Non-conference losses at the Milwaukee School of Engineering, no hope against Hope International, sluggish against UC Santa Cruz. A win on Dec. 4 in the seventh-place game of the Fulmer Tournament in Redland came up against American Sports University, which snapped a 44-game losing streak (it had last won in January of 2009 against NYU-Polytechnic). Elmquist had a game-high 25 points, including 13-for-14 at the free-throw line, and was given the tournament’s Sportsmanship Award.

Caltech actually ran off three wins. In a row. (One had to be vacated because of an NCAA infraction, but we’ll get to that later). It outlasted UC Santa Cruz in a rematch, 63-62, in the SCIAC Classic at Braun Gym. Elmquist had 17 points, four blocks and six rebounds in 38 minutes and became the 11th player in the program to go past 1,000 points. He also broke the school mark for career blocks.

“Ryan has worked so hard for four years and today is a great testament to that hard work. He is a great example of what a Caltech student-athlete should be,” Eslinger said.

The New York Times caught wind of the winning ways and dispatched a reporter to help frame it, finding out that the basketball team’s roster had a streak of having more than 300 players who got perfect 800 scores on the math part of the SATs.

It also mentioned that Elmquist had to miss a recent practice while going on a job interview.

“In the next couple of weeks, he’ll have a job — making more than you and I combined, probably,” Eslinger said.

Once SCIAC play started, it was like broken calculators all over again.

An overtime loss at home to Redlands by four. Caltech forced OT when Elmquist grabbed a rebound with five seconds left in regulation, fed teammate Todd Cramer, and he hit a 3-pointer with a second left.

A loss to Whittier by two. A one-point loss to LaVerne. Elmquist had a 28-point, 10-rebound game against Pomona-Pitzer, but Caltech lost by six on the road.

An 0-11 conference mark mounted by early February. Losses by 16 at Cal Lutheran and eight at Claremont-Mudd-Scripps lead into the final home game of the season on Feb. 22. Elmquist needed one point to move into second place on the program’s all-time scoring list.

Occidental, which a month earlier on its home court registered a 10-point win over Caltech and kept Elmquist to six points and only three free throw attempts, held the lead for most of the contest, including 45-37 with 4:33 to play.

At that point, Caltech scored the next nine points.

Elmquist, playing in the post, was fouled time and time again. Which helped since Caltech had made a season-low 12 field goals, shooting just 25 percent from the floor. It helped that the Beavers committed just five turnovers and were holding Oxy to the lowest score of an opponent all season long.

Elmquist went to the line with 3.3 seconds left, the game tied. He put Caltech ahead with his first free throw. He missed the second. Oxy rebounded and tried a shot from behind midcourt at the buzzer wasn’t close.

“I had no idea,” Elmquist told the L.A. Times’ Plaschke afterward about whether he could make the final free throw. “But I knew I would never be challenged with anything this athletically hard the rest of my life, so I knew I better do it now.”

Easy as pi, Plaschke wrote.

Several hundred students rushed the court, including the school president Dr. Jean-Lou Chameau. Two of Elmquist’s teammates from their freshman year were now seniors and could appreciate better the achievement, including Ziying Wang from Troy High in Rowland Heights, who only played one minute in a loss to Wisconsin Lutheran that season.

Said Chameau: “When you’re president of Caltech, you witness scientific breakthroughs, Mars landings, and any number of other memorable events. Storming the court with Nobel laureate Bob Grubbs will certainly rank high on my list of Caltech memories.”

“Tonight’s win is a testament to the hard work each member of this team, the alumni and the supporters have put into this program. I hope that everyone who has participated in Caltech men’s basketball is able to celebrate a little bit tonight,” Eslinger said. “We still have goals and aspirations that we want to accomplish as a program and this win is another step towards meeting these objectives.”

The school held a midday media session the following day to celebrate its win. One player still who had not been to class yet couldn’t stop smiling about it.

“I wrote all my professors and told them I could not make it today because I was attending a basketball press conference,” Elmquist said. “I could never in a million years imagine writing an e-mail like that.”

In a follow-up story with the Twin Cities Pioneer Press, Elmquist was asked if he knew the odds of a team losing 310 straight games in its conference.

“I don’t even want to know,” he said with a laugh.

He added: “Shooting the free throw, I had no idea what would happen. Thinking back, I should have tried harder to miss the second one so they couldn’t get the rebound.”

In April of 2011, Elmquist did an online Q&A personality profile with his next employer, Google, as an ice breaker before he graduated a term early and was set to start work there in June after taking a backpacking trip through Europe with a friend.

He said he studied computer science because “the process of breaking down a complex problem into manageable pieces to solve is really fun. I enjoy the projects that we get to work on in class and the fast turn-around when you work on those projects. It’s not possible to see your results almost immediately in many other fields.”

His advice to students who are studying that field: “Don’t be discouraged when your programs don’t work the first time; we all have to debug every once in a while.”

And his takeaway from sports: “I think breaking a 310-game losing streak has shown that it’s worthwhile to persevere!”

The aftermath

After the euphoria of that 2011 streak-breaking win, Caltech lost another 55 SCIAC games in a row. That follow-up streak ended with a buzzer-beater against Redlands on Feb. 3, 2015.

The 2011-12 team finished 1-24, its only win by one point over visiting Bard, which by now becoming the Beavers’ whipping boy.

In ’14-’15, it also had a rare back-to-back wins. The men’s team hadn’t won two conference games since in the 1970–71 season. The last set of back-to-back conference wins occurred 61 years prior in the 1953–54 season, when the team won three straight conference games to claim the SCIAC Championship.

The high point was, by 2015-16, it was 9-16, 7-9 in conference, and launched into a 3-0 mark to start the SCIAC season.

Sports Illustrated’s interest was piqued.

In November of 2015, the magazine came around to do a piece on the program called “Revenge of the Nerds,” based on coach Eslinger’s ability to at least endure not-so-terrible seasons with some promises of better times ahead.

A key part of the story rewound a few years and set a scene from that epic 2011 year-ender: Eslinger was sitting in a dorm room with Elmquist, pounding vodkas, pondering the 310-game conference streak.

Elmquist finally told his coach “I can’t believe that I’m going to go four years and not win one f—-ing (conference) game.”

Going back to that weekend before the 2011 game against Occidental, SI reported that Eslinger had been playing a pickup game with Doug Eberhardt, a coach from Vancouver who was in L.A. for the NBA All-Star game. He had recently been scouting with the New York Knicks and Eslinger peppered him with questions until, finally, Eberhardt said: “Why don’t I just give you (coach Mike) D’Antoni’s playbook. I’ve got it out in my car.”

Eslinger stayed up late that night studying the diagrams. He remembered how Occidental’s switching defense had hurt Caltech the first time they played. What if, he now wondered, he just ran never-ending pick-and-rolls between the Elmquist and freshman point guard Todd Cramer? They would essentially play the role of the Knicks’ Amare Stoudemire and Steve Nash.

It had been working, even as Oxy pulled out to that 45-37 lead At a time out, Eslinger told his team: If we let them score again, we lose.

Caltech’s defense came through.

With eight seconds left in the tie game, the play was for Caltech sophomore guard Collin Murphy to set up for the last shot. But when Oxy’s defense didn’t collapses on point-guard Cramer, he saw Elmquist slip past a screen. Cramer lobbed the ball to him instead of Murphy. Elmquist went up and was fouled. Oxy called a time out.

The SI story continued:

As the team walked to the sideline, Eslinger racked his brain for what to say. And then it came to him. “This is perfect,” he said to Elmquist, a 67 percent free throw shooter. “I read a study about field goal kickers. It proved that icing doesn’t work!”

For the first time in a life of constant inquiry — of acing the ACT, of spending a summer working with the autonomous navigation of mobile robot teams at University of Minnesota, of subjecting everything to a decision matrix — Elmquist felt his mind go blank. He heard nothing, remembers nothing.

Swish.

The second free throw missed. Oxy’s desperation heave went wide. And then: nerd bedlam. Students stormed the floor. Nobel winners celebrated. On the baseline, television cameras rolled. No one wanted to leave the court.

The next day, news of the win even briefly led the Caltech website, just above coverage of the lab’s development of a new Mars Rover…

The SI also noted that in July of 2012, Caltech turned itself into the NCAA for infractions that is incoming athletic director discovered.

NCAA had a rule that student-athletes must be taking a full course load to be eligible to play sports, but that was a gray area for Caltech students. They don’t officially take a full course load until the end of the third week of every term because they are allowed to shop the difficult classes before making final decisions.

AD Betsy Mitchell, a former Olympic swimmer at Harvard, said she found 30 instances over four years when athletes were briefly ineligible as they were setting their schedule.

She felt there was only one thing to do: Self-report.

Caltech initially decided to punish itself with a 2012-13 postseason ban on 12 sports, vacating wins achieved by teams using ineligible athletes during that four-year period, eliminating off-campus recruiting for the upcoming school year and paying a $5,000 fine.

At a time when scandals raged at USC and Miami, the NCAA accepted that — and added a public censure and three-year probation, rather than commend Caltech for being a model of integrity. How rich was that.

The decision came to mean that Caltech’s 2011 victory over Nazarene amidst the early three-game win streak that year had to be forfeited. So officially their record became 4-21.

But that final streak-busting win over Oxy stood as legit.

When all the math was done, whether or not it is eventually referenced in a “Big Bang Theory” spinoff, that one-point win all that mattered really to Caltech, its students, its faculty, its coach, and a long-ago, data-driven graduate named Ryan Elmquist.

Who else wore No. 23 in SoCal sports history?

Make a case for:

Kirk Gibson, Los Angeles Dodgers outfielder (1988 to 1990):

Just three seasons, eh? And, for all that, one imperfect swing.

“I probably had no business up there,” Kirk Gibson said during an MLB Network program that aired in 2011 –23 years after No. 23 was “there,” limping into the left-handed hitting batter’s box at Dodger Stadium, almost naively trying to will a team to victory, one that also probably had no business being in the 1988 World Series.

It’s the bottom of the ninth inning of Game 1 of the 1988 World Series, with two outs, and a full count. The Dodgers were someone still breathing against the heavily favored Oakland Athletics. They trailed 4-3, and future Hall of Fame reliever Dennis Eckersley was staring them in the face.

Gibson, on two bad legs, didn’t blink.

None of this made any sense, and in a sense, that’s why it’s so memorable. So Hollywood. It remains by many the Greatest Sports Moment in Southern California Sports History.

After nine seasons wearing No. 23 for his hometown Detroit Tigers — which came after four years of wearing No. 23 as a flanker and defensive back for Michigan State’s football team — Kirk Gibson was convinced by Dodgers general manager Fred Claire to come to L.A.

It only lasted three seasons. But it was never uninteresting.

Gibson was made a free agent by a labor arbitrator based on a decision about owners involved in collusion, otherwise he would still be in Detroit. Claire got him for $4.5 million over three years. Gibson’s agent had reportedly been seeking a three-year, $4.8 million deal to stay in Detroit.

Gibson’s hey-day baseball moment had been four years prior, carrying the Tigers to the 1984 World Series title, capped off by an eighth-inning, three-run homer into the upper deck at Tiger Stadium off San Diego’s future Hall of Fame reliever Goose Gossage.

Gibson was known — and somewhat adored — for his hard-nose football mentality (it would get him inducted into the College Football Hall of Fame eventually) as well as living the life as an avid hunter and fisherman. Joe Posnanski felt compelled to include him in the 50 most famous baseball players of the last 50 years because of that wild nature:

“Gibson’s fame was certainly mixed. … I tend to believe careers are often what they’re supposed to be, and I’m not sure that a mercurial player like Kirk Gibson—who played with such wild abandon—can stay healthy or be metronome consistent. He was a bright-lights performer. He was a ferocious competitor. He was a football player. Had he stayed in football, who knows, his bust might be in Canton right now. But baseball wouldn’t have been the same.”

Several defining moments of that ’88 season for Gibson started with his angry reaction to having black shoe polish inside in his cap by new teammate Jesse Orosco during spring training, and changing the ethos of a team roster that was why Claire brought him in the first place.

“I was with the Tigers my whole career before this, under the late Sparky Anderson, a real business–type guy. No screwing around,” Gibson explained to Bob Costas and Tom Verducci in that 2011 MLB Network show. It was highlighting that 1988 World Series Game 1 as one of the Top 10 best games in the sport’s history.

“I came to the Dodgers that spring training and … it was a different atmosphere and I was a little uncomfortable with that. I remember we were doing bunt drills one day and Pedro Guerrero picked up the ball and threw it down the right field corner and everybody laughed. And I was like: That’s not funny. I remember the St. Louis Cardinals the previous year running the bases on the Dodgers like a Little League team.”

As Dodgers team historian Mark Langill noted in a story:

Dodger players were probably not aware of Gibson’s reaction to “levity” as a Detroit prospect in 1980 when veteran pitcher Jack Billingham derisively called him “rookie” as he did with other young players. Gibson warned Billingham to stop. When Billingham chided Gibson’s presence in the trainer’s room hours before a game — “That kind of wonderful treatment are we getting today, rook?” — Gibson snapped. According to his autobiography, “Bottom of the Ninth,” Gibson jumped on the 6-foot-5, 230-pound Billingham and pinned him on the floor. “Rookie me one more time!” Gibson screamed. “You say one more word, and I’ll rip your windpipe right out of your throat! You’ll never talk again! You hear me?”

Gibson turned around and challenged the rest of the stunned clubhouse. Silence. Gibson nodded and calmly said, “Thank you.”

== August 20: The Dodgers trailed Montreal, 3-2, going into the bottom of the ninth inning on a Saturday evening game. Gibson’s one-out infield single scored pinch-runner Dave Anderson to tie the game. One out later, Gibson stole second. With John Shelby at the plate, Expos pitcher Joe Hesketh spiked a pitch that went to the backstop. This was long before stadium renovations added more seats to that area and cut down the foul territory. Gibson not only went to third base, but his helmet went flying off as he kept on going and scored sliding in to win the game, throwing his fist in the air.

== In Game 3 of the National League Championship Series against the favored New York Mets, Gibson, already limping around in muddy left field at Shea Stadium drenched by recent rain, stumbles but manages to lift his glove up and behind him to snare Mookie Wilson’s opposite-field liner and rob him of an extra base hit. This was after a moment earlier where Gibson bobbled a ball hit to him by Darryl Strawberry, but he was able to recover and throw out Keith Hernandez trying to go to third base.

== In Game 4 of the NLCS at Shea Stadium, Gibson’s 12th inning home run with two outs off Roger McDowell gave the Dodgers a winning 5-4 margin. Gibson had been mired in a 1-for-16 slump to that point. It was the game where Orel Hershiser came in on relief to get the last out, the save, and tie the series at 2-2.

Gibson woke up lousy for Game 1 of the World Series. He had not only a bad left hamstring from stealing second base in Game 5 of the NLCS, but also banged up his right knee sliding into second on Game 7.

Three days fell between the NLCS and World Series, but there was no travel. By a fluke of the rotation, the National League team hosted the first two games, even though Oakland had a far better record.

“I got up that morning about 4:30 and started to walk across the floor and I’m thinking, ‘That doesn’t feel too bad’,” Gibson said in the MLB Network show. “And then I jogged across the floor and I said, ‘Uh, oh, we might have a problem here.”

He said he alerted the team trainers, saw a doctor, and had several pain-relief injections.

Game 1 of the World Series started with him in the trainer room icing both legs. He not only didn’t appear in the opening lineup, he didn’t go out for pre-game player introductions.

“I just knew I couldn’t play, I couldn’t overcome it,” he said. “I knew we’d be a better team without me.”

As the game played out, after Jose Canseco’s second-inning grand slam would provide all the runs the Athletics thought they might need, and Dave Stewart effectively keeping the Dodgers in check, the ninth inning came around with a one-run deficit, and some of the fans already leaving the stadium to beat the traffic.

Gibson, Mike Davis and Dave Anderson were the only ones left on the bench as the Dodgers’ Nos. 6, 7 and 8 hitters were coming up.

“I had this dream in my mind if Davis got on (hitting in the) eighth (spot) I could hit (in the) ninth (spot),” said Gibson.

He also heard Vin Scully, in the NBC national broadcast, say before the inning started as the cameras panned the dugout: “There’s no Kirk Gibson, he won’t be playing tonight for sure.”

“And I just said, ‘My ass,’” Gibson told Costas and Verducci.

Gibson threw on his jersey and took some 20 practice swings off a tee into some netting down the ramp from the dugout to the locker room, with bat boy Mitch Poole not only helping, but also sent by Gibson to alert Lasorda of his plan.

After Mike Scioscia popped out and Jeff Hamilton took a called strike three against Eckersley, Gibson is now seen in the dugout by the TV cameras with a helmet, a bat and his batting gloves on.

“I appeared a little earlier than I was supposed to,” Gibson admitted, “but I didn’t really care if they knew I was going to hit or not.”

Mike Davis, as per Gibson’s plan, came up to pinch hit for shortstop Alfredo Griffin. Davis it hitting .196, and .106 over his last six weeks of the season. Somehow, he coaxed a rare walk out of Eckersley.

“And look who’s coming up,” Scully tells the audience. “With two out you talk about a roll of the dice. This is it.”

“My teammates had counted on me in certain situations,” Gibson said. “That’s why I said I gotta go up there and see what I can do. The fans wanted to see what I could do. And that’s why I’m there.”

Gibson had already told his wife to head home with their 2-year-old son because he wasn’t going to play. Now he was.

First pitch: Fastball fouled off to the left. Gibson staggers out of the batter’s box.

“You can see the first swing wasn’t real pretty,” Gibson says. “My base (foundation) is not real good.”

Second pitch: Fastball fouled back.

“That hurt,” Gibson says. “We’re 0-2 (on the count) and I’m going into full emergency — I really spread out (both legs) and I got my hands in tight and kind of duck down (in a crouch).”

Third pitch: Fastball dribbled down the first base line, going foul.

As Gibson limps up the line, he converges with first baseman Mark McGwire picking up the ball and Eckersley coming over to see if he can field it. Gibson does a quick turnaround and heads back.

“I’m just thinking about fouling balls off off,” says Gibson, as the Dodgers ballboy brings home plate umpire Doug Harvey a new handful of balls.

Fourth pitch: Fastball sails outside.

Gibson lunges for it but doesn’t swing. A’s catcher Ron Hassey sees an opportunity to throw down to first base to try to pick off Davis, who just does get back in safely. Had he been out, game over.

Fifth pitch: Fastball sails high and outside.

Gibson stands upright, hitches his belt and take a short walk outside the batters box. “Two-and-two,” says Scully.

Sixth pitch: Fastball runs outside. Gibson lunges again, with his left foot sliding behind home plate.

Hassey receives the pitch, stands up and sees Davis running to second. Hassey’s glove brushes up against the left arm of Gibson, who spins away to avoid contact. Hassey hesitates and doesn’t throw, briefly looking back to Harvey to see if there is any interference. No gesture from Harvey. Gibson turns his back and walks out of the batter’s box again. Davis’ steal is successful. Had he been thrown out, or Gibson called for interference, game over.

“Now the Dodgers don’t need the muscle of Gibson as much as a base hit (that could send Davis home to tie the game and go into extra innings),” says Scully.

A tie game really doesn’t help the depleted Dodgers. But it beats losing.

Before the seventh pitch, Gibson calls time and backs out of the box. This is the moment he says he recalls the words of Dodgers scout Mel Didier: “As such as I’m standing here and breathing, partner, if Eckersley gets you 3-and-2, he will throw a backdoor slider.”

Eckersley had thrown 17 fastballs to this point in the inning. No sliders.

Seventh pitch: A backdoor slider, dips toward the outside part of the plate, just below belt high.

Gibson lunges for it, swings with his arms, right hand comes off the bat, left leg comes across the plate, right leg stays stiff, and the ball is lofted toward right field.

“High fly ball into right field … she is gone!” proclaims Scully.

Gibson rounds first in a slow measured trot and throws his right arm up with his hand balled in a fist after first base coach Manny Mota slaps him on the back. Gibson then thrusts both arms in the air — reminiscent of the home run he hit for the Tigers in the 1984 World Series.

Gibson rounds second, cocks his right arm and does two pumps, drawing his arm back to his right side, elbow out.

“In a year that has been so improbable, the impossible has happened!” Scully says.

Gibson rounds third and slaps the hand of third base coach Joe Amalfitano, who then waves his left arm to slap him on the rear end.

Making his way down the third base line, Gibson sees Mickey Hatcher holding out his hands to slap. More teammates are around him: Orel Hershiser, Tim Crews, Mike Sharperson, Rick Dempsey, pitching coach Ron Perranoski. Steve Sax is at home plate screaming. Tracy Woodson hugs Gibson from behind.

In the NBC post-game interview with Costas, Gibson explains his thoughts as the crowd behind him ceases to quiet down: “I was very disappointed I knew I couldn’t play … I saw the opportunity. I knew if (Eckersley) got a guy on base, the pitcher was coming up, I could hear the fans cheering and I could suck it up for one A-B and maybe something good would happen.”

And Gibson then looks over his shoulder toward home plate.

“And … it happened.”

Gibson summed up the rest in the MLB Network interview: “It was an ugly swing. You just needed to strike the baseball properly. All wrist and hands. …

“Throughout my career, I had a lot of people who were critical of me and I told my mom and dad many times — because it really hurt them — I said, don’t respond to that. We’ll have our day. Yeah, here it is, right here.

“You can’t even imagine how it feels to come through in a moment like this. In the end, it’s a part of the history of the great game of baseball. And then how this influenced the whole rest of the series. We were fortunate to have people underestimate that team. Fortunately in the end we won out in that series. That’s a tribute to all my teammates.

“Over time, the personality of what it really means has come out. Trust me, to all the fans out there, I’m honored to be the guy. I’m not really sure why it was me. I worked hard throughout my career. It’s who I saw myself as being.”

For his hitting .290 with 25 homers, 88 RBIs and 31 stolen bases, Gibson, who had not led the NL in any one category, was voted the National League’s MVP Award. Teammate Orel Hershiser had a better case to winning MVP (finishing sixth in the voting) to go with his NL Cy Young Award. It was Gibson’s grit and grind led voters to name him most valuable to the team.

The city celebrated a couple days after they won the World Series. Lasorda danced. Gibson just tried to stay upright.

In his first at-bat on Opening Day, 1989, at Riverfront Stadium in Cincinnati, Gibson, hitting third and playing left field, lined a single to right field to drive home new teammate Willie Randolph and give the Dodgers a 1-0 first-inning lead.

Gibson went to second on an Eddie Murray groundout, stole third base and then came around to score, with a pump of the fist that called back his ’88 heroics, on catcher Jeff Reed’s throwing error. In the fifth inning, Gibson homered off Danny Jackson.

But the Dodgers lost the game, 6-4.

In the Dodgers’ home opener on April 13, after raising the World Series banner, Gibson struck out in the bottom of the sixth, the second time he struck out in the game against Houston. In the seventh inning, he was replaced in left field. He was still hurting.

One goofy thing about 1989: Topps baseball cards issued a set of those who made the previous year’s All-Star Team. Gibson was included. But he never was on that NL All Star team — or on any All Star team in his entire career. They decided to give him an “All Star” card and listed him as “PH.” Gibson had actually been invited to be on the 1985 AL All-Star team (a year after his famous 1984 season, which was his first as a regular player) and on the 1989 NL All-Star team (a year after his famous homer in ’88), but he declined both times.

Gibson played only 79 games in 1989 and 89 games in 1990. He hit just 17 homers and drove in 66 runs those two seasons combined. He was also moved to playing more center field. He didn’t like it so much for the demand on his legs.

In July of 1990, Gibson announced he was tired of L.A. and wanted to be closer to his family in Michigan, hinting he would leave after his contract ended. By September, Gibson’s agent said that unless the Dodgers made some “personnel moves” — getting rid of left fielder Kal Daniels so Gibson could move back there from center field — he might consider staying.

Daniels had been hitting .296 with a team-best 27 homers. Gibson finished the ’90 season with just nine hits in his final 60 at bats and without a home run after Aug. 11.

“Some people think I’m selfish because I don’t feel I can play center field,” Gibson said. “I think I’ve proved what I’ll do for the team. I’ve played hurt. I’ve taken injections, undergone surgery. I’ve played different positions, batted in different spots in the order. I’ve done just about anything they’ve asked. .. I tried and now I think it’s too much for me and now suddenly I’m selfish?”

“I certainly don’t have anything against the Los Angeles Dodgers or the city of Los Angeles or the fans. I was never upset at the Dodgers or anyone else. All I have been is honest, about today, about tomorrow, about next year. It’s really not up to me at this point. As far as the future, or beyond this year, we’ll just have to wait. I’m under contract to the L.A. Dodgers, and I’ll fulfill that contract.”

When the Dodgers signed Darryl Strawberry in the offseason, Gibson left as a free agent to Kansas City. Then to Pittsburgh. He put in three more years with the Tigers (’93 to ’95) returning to his No. 23. When it all ended, with 17 seasons, he was never once voted onto or added by the manager to either the NL or AL All Star team — mostly because Gibson himself declined the later. Even after he had five straight seasons of 20 homers/20 stolen bases from 1984 to 1988.

The bat that Gibson used and the jersey that he wore on Oct. 15, 1988 went up for auction in 2017, as well as his 1988 NL MVP Award and World Series replica players trophy.

Now the manager of the Arizona Diamondbacks, Gibson called a press conference at the Los Angeles Sports Museum in downtown L.A. and explained that these were not only items he owned, but he would accept the winning bid and donate proceeds to charity.

“That’s not an appropriate question,” he said when challenged about the ownership of the items. “I don’t know what that has to do with anything. … I’m really at peace with what I’m doing.”

I thought it made no sense — this stuff belonged in some shrine, and the stuff likely belonged to the team. But I went ahead with the ruse for the sake of the story.

“I mean, they were mine,” he said, adding that owner Peter O’Malley also gave him a giant LeRoy Neiman lithograph of that moment and allowed players to keep their jerseys and other items.

“I’d like to see (the items) in the Hall of Fame,” said former manager Tommy Lasorda, himself a Hall member, “but if he can help a charity more, there’s nothing wrong with that.”

Chad and Doug Dreier of the Dreier Group in Santa Barbara paid $1.19 million for the five items, which included the bat ($575,912), jersey ($303,277), helmet ($153,388), NL Most Valuable Player Award ($110,293) and World Series trophy ($45,578).

(By the way, what happened to the home run ball? It’s probably gone forever).

Gibson wasn’t done fundraising after he was diagnosed with Parkinson’s Disease in 2015.

Starting in 2018, the Dodgers announced a special promotion for anyone who wanted to pay for a ticket to sit in the seat where the team guessed was the spot of the home run landing in the right field pavilion could do so with a ticket package with proceeds going to the Kirk Gibson Foundation for Parkinson’s. The bench seat had been painted blue and gold.

In 2023, street artist Corie Mattie unveiled a mural in the Atwater area of L.A. — on the wall of Bill’s Liquor store on Glendale Blvd. — to honor Gibson as well as his foundation, which incorporates the No. 23 at the center of its logo.

The Dodgers have yet to retire No. 23. It did honor him with its Legends Wall as well as create a bobblehead to mark the occasion.

It reminded us of when the Dodgers started in the bobblehead giveaway business in 2001 and made Gibson one of the first giveways. Vin Scully took at look at it and laughed. “It looks more like Stacey Keach,” he said, referring to the Hollywood actor.

Claire once said: “The Gibson chapter was a success. I don’t know if in the history of the game there was a player who signed as a free agent and became a most valuable player the next year. That speaks for itself.”

Eric Karros, Los Angeles Dodgers first baseman (1991 to 2002):

Best known: The all-time leader in Los Angeles Dodgers history with 270 home runs, which stands third on the franchise list behind Duke Snider (389) and Gil Hodges (361). Also sixth in the franchise with 976 runs batted in. The 1992 NL Rookie of the Year — .304, 20 HRs, 88 RBIs at age 24 — was fifth in the 1995 NL MVP voting, when he captured a Silver Slugger Award (.298, 32 HRs, 105 RBIs), and he followed that up in ’96 with a 34 HR and 111 RBI season. His most productive statistical year was 1999 — .304, 34 HRs, 112 RBIs. In 2015, the Los Angeles Times asked online readers to name their 10 greatest Dodgers of all-time, more than 14,000 ballots were cast and Karros received …four votes. “The four people who voted for me got it wrong,” Karros said. “I’d be the first to tell you I wouldn’t be in a top-20 list of Dodgers.” It’s not like Karros has disappeared. He’s a baseball analyst for Fox as well as for the Dodgers on SportsNet L.A. since he retired in 2004.

Not well remembered: Karros, like Gibson, was never included on an MLB All Star roster. During Karros’ career, the NL All Star first basemen actually picked included Fred McGriff, Will Clark, John Kruk, Andres Galarraga, Gregg Jefferies, Jeff Bagwell, Mark Grace, Mark McGwire, Sean Casey, Todd Helton, Ryan Klesko and Richie Sexon. Eventual perennial selection Albert Pujols made his first All Star team in 2001 as a third baseman. Karros’ best chance to make the team came in 2000, when he was hitting .265 with 25 HRs and 70 RBI at the All Star break, but he was passed over for McGwire (.303, 30 HR, 69 RBI), Todd Helton (.383, 21 HR, 70 RBI) and Galarraga (.294, 20 HR, 62). But when McGwire bowed out with an injury, NL manager Bobby Cox chose shortstop Edgar Renteria (.273, 10 HR, 38 RBI) to replace him.

Not well known: When Gibson left the Dodgers after the 1990 season, Karros inherited the number in his rookie season. Karros once told us: “I had No. 26 through high school and college, and in the minor leagues had No. 35. My first year on the roster I was given No. 23 with the understanding that the general manager, Fred Claire, was responsible for assigning the numbers to new players. I was obviously aware of the significance of the number, not only in Dodger history, but in general, with the popularity of Michael Jordan at that time. In fact during my run with the Cubs in ’03, Jordan was around quite a bit during the September chase and in the locker room for our playoff celebrations. During one conversation we had, he brought up the fact that I was the guy who wore 23 for the Dodgers. I ended up wearing No. 32 in Chicago — reversing No. 23 — because the team had not issued No. 23 since Ryne Sandberg retired. My next choice was No. 14, after Pete Rose, who was my favorite player as a kid, but that was already retired for Billy Williams.”

David Beckham, Los Angeles Galaxy midfielder (2007 to 2012):

Best known: His joining the Galaxy for a five-year, $32.5 million contract was official when his wife Victoria, aka Posh Spice, appeared on “The Tonight Show with Jay Leno” after the couple arrived in L.A. and gave him a No. 23 Galaxy jersey with his name on the back. A spectacular press conference at the Galaxy’s home field in July, 2007 followed, drawing 700 media members and some 5,000 fans. Even the MLS official website will admit that Beckham’s arrival in the U.S. “changed the league forever,” starting with “The Beckham Rule” that redefined how the league brought over new “Designated Players” to liven up the roster.

“I’m coming there not to be a superstar,” Beckham, who had a film named after him (“Bend It Like Beckham” in 2002), who sported 65 tattoos, and who bought an $18 million home on San Ysidro Drive in Beverly Hills, said of the journey to American football. “I’m coming there to be part of the team … I’m not saying me coming over to the States is going to make soccer the biggest sport in America. That would be difficult to achieve. Baseball, basketball, American football, they’ve been around. But I wouldn’t be doing this if I didn’t think I could make a difference.”

His first four seasons in L.A., playing alongside Landon Donovan, was much more about his celebrity than any sort of production on the field. In ’09, his iconic free kick in the first half of extra time led to a game-winning goal in the Western Conference title game against Houston, and he played the full 120 minutes of the MLS Cup against Real Salt Lake, converting a penalty kick in the game’s decisive shootout of a 5-4 loss. It took five seasons of stops and starts before Beckham was on an MLS title team — in 2011, he was second in the league with 15 assists during 26 regular season games, but also tied a team record with 10 yellow cards, leading to a pair of one-game suspensions. A 1-0 win against Houston in the ’11 MLS Cup came on a goal by Donovan, assisted by Beckham and Robbie Keane. He decided to stick around — another two-year contract was signed, and in 2012, the Galaxy somehow brought themselves up from a fourth-place Western Conference regular season to repeat as MLS champs with a 3-1 win over Houston. Near the end, Beckham was substituted off and received an ovation from the fans as the game was on the Galaxy’s home field. Even with another year on his contract, Beckham said that was his walk-off game for the franchise. He retired from playing in 2013.

A Beckham statue has sat outside the Galaxy home field since 2019, honoring his 118 appearances and 20 goals and 40 assists — and 27 yellow cards. His honors in the MLS: Comeback Player of the Year (2011), All Star appearance (3), and MLS Best XI (2011).

Not well known: Beckham wore soccer traditional No. 10 as well as No. 7 through most of his ballyhooed career with Man U., but he he picked No. 23 with Real Madrid to honor Michael Jordan — and that’s what he kept when he signed with the Galaxy.

Not well remembered: When Beckham left the MLS as a player, one of his Galaxy contract provisions allowed him to buy an MLS expansion franchise (in any market except New York) at the cost of $25 million. That happened in 2014 when he landed a team in Miami, but it didn’t start until 2020 because of stadium delays. The team debuted on March 1, 2020 — and lost 1-0 to the Galaxy.

Harold Miner, USC basketball guard (1989-90 to 1991-92):

Best known: The 6-foot-5, 185-pounder out of Inglewood High known as “Baby Jordan” wore No. 23 during his three seasons at USC where he averaged 23.5 points a game. Miner admitted he dreamt of attending North Carolina, Jordan’s alma mater, but Trojans coach George Raveling reeled him in. “You don’t have to go to a car dealership 10 times to spot a Mercedes,” Raveling said about the fact he’d only seen Minor play four times in high school (where Minor wore No. 33). Miner averaged 29.5 points, 10.5 rebounds and four assists in leading Inglewood to the quarterfinals of the CIF-Southern Section 4-A playoffs in his senior year. At USC, Miner became the Pac-10 Player of the Year as well as Sports Illustrated’s choice as college player of the year in 1992 — ahead of Duke’s Christian Laettner and LSU’s Shaquille O’Neal — after he led the Trojans to the No. 2 seed in the Midwest Region, only to lose on a last-second shot to Georgia Tech in the second round. After three seasons as first team All-Pac 10, including the 1990 conference freshman of the year, Miner declared himself eligible for the NBA, having become USC’s all-time leading scorer with 2,048 points. USC retired his No. 23 in 2012 during a USC-UCLA game. The 12th overall pick by Miami had reportedly more in Nike endorsement money ($14 million) than his five-year, $7.3 million deal with the Heat.

Not well remembered: Knee injuries shortened his NBA career, but the highlight may still remain two NBA Slam Dunk titles in ’93 and ’95. He was out of the game at age 25. “I always felt the worst thing to happen to Harold was the ‘Baby Jordan’ tag,” Raveling would say.

Dustin Brown, Los Angeles Kings right wing (2003-04 to 2021-22):

Best known: During his 18 seasons with the Kings, starting at age 19 as the 13th overall pick in the 2003 draft, the team captain hoisted the Stanley Cup twice. In 2007, he was the youngest, and first American-born, captain in franchise history, holding that for eight seasons, including the two Stanley Cup runs. His 1,296 games played as a King is second all-time to Kopitar, his 325 goals are sixth in the franchise history, and his 387 assists are eighth best. His 42 game-winning goals are also No. 6 on the franchise list, and his 3,360 shots are second only to Marcel Dionne. When the Kings retired his No. 23 jersey in 2023, it also included putting a statue of him outside the team’s arena, depicting him hoisting the Stanley Cup. “Throughout my 18 years, I experienced the highest of highs and the lowest of lows. C or no C I always wanted to retire a King,” Brown said during the retirement number ceremony. “Seeing my jersey raised to the rafters, my only hope is that in the future when you look up and see it hanging there, you think not about my achievements but our achievements.”

Not well remembered: After the ’14 title season, Brown was named the NHL’s Mark Messier Leadership Award, adding his name to a list that includes Chris Chelios, Sidney Crosby and Kings teammate Anze Kopitar. Brown also received votes for the Lady Byng Award for sportsmanship and the Selke Trophy for top defensive forward.

Kenny Washington, UCLA basketball (1963-64 to 1965-66):

Best known: The key sixth man on Coach John Wooden’s first two NCAA title teams, coming out of the Athletic Association of Western Universities, Washington scored 26 points with 12 rebounds as No. 1 UCLA outlasted Duke in the 1964 title game to complete a 30-0 season. The next year, a 28-2 season ended with No. 1 UCLA crushing Michigan in the title game behind Gail Goodrich, while Washington scored 17 points to be on the All-Final Four team.

Not well remembered: In 1974, Washington became the first head coach of the Bruins women’s basketball team, posting an 18-4 record with Ann Meyers as the star.

Jonathan Franklin, UCLA football tailback (2009 to 2012):

Best known: The Bruins’ all-time rushing leader out of Dorsey High had 4,403 yards on 788 carries — the only player in the program history to exceed 4,000 yards and 700 carries. In his senior season, Franklin had 2,057 yards from scrimmage and 15 touchdowns, almost twice the numbers from his sophomore and junior seasons. His 31 touchdowns is also third all time behind DeShaun Foster (39) and Gaston Green (34).

Not well remembered: Franklin was first-team All-City as a running back and third-team as a cornerback, named Coliseum League Player of the Year for Dorsey.

Diana Taurasi, Don Lugo High School (1996 to 2000):

Best known: Before she won six Olympic gold medals, became the WNBA’s all-time leading scorer, a three-time league champion, a two-time finals MVP, a 14-time all-WNBA team member, plus a three-time NCAA champion, two-time Honda Award and Naismith Award winner, four-time USA Basketball Female Athlete of the year and six-time gold medal winner in the Summer Olympics … she wore No. 23 at Chino High right across the street from her house. There, she scored 3,047 points, second all time to Riverside Poly’s Cheryl Miller in the CIF-Southern Section leaders. A 52-point game in a season-opening 81-76 overtime victory over Moreno Valley started her senior season and was her fourth 50-plus point game. A Time magazine interview with Taurasi when she announced her retirement from the WNBA in early 2025 included a Q&A that asked: Going back to your childhood in Southern California — what drew you to basketball? Her reply: “As a little kid, being a kid of immigrants coming to this country, basketball always made me feel a part of something. It always made me feel comfortable. It brought me to a place where, you know, I could love others. I could love myself. It really is, to me, the one thing that always loved me back.”

Not well known: When ESPN listed the Top 100 pro athletes of the 21st Century in 2024 (only a quarter way into the actual century), Turasi was slotted at No. 21 as her bio included: Taurasi was born in 1982, when the NCAA tournament began for women. Twenty years later, she won the first of three consecutive NCAA titles with UConn. Now, 22 years after that, she’s still going at 42 as the oldest active player in the WNBA. The only player in the league to hit 10,000 points, Taurasi has spent her entire career with Phoenix and has led the WNBA in scoring five times. Playing in her sixth Olympics this summer, she is revered for her longtime leadership of Team USA as well as the Mercury, and for her unwavering swagger. There is no mistake that perhaps the most fitting honor for Turasi came in 2019, when the WNBA made her the logo. The league won’t say that. But … the silhouette has Taurasi’s shot, her shape and her trademark bun. “The game got better because Taurasi played it,” USA Today’s Nancy Armour wrote. “It will continue to do so because she played it her way.”

Have you heard these stories:

Jackie Joyner, UCLA women’s basketball (1979-80 to 1984-85):

Best known: The “Jackie of all trades” was elected to the UCLA Athletic Hall of Fame in 1996, most notably for her achievements in track and field. The international star in the long jump and 60-meter hurdles, she won the silver award in the heptathlon at the 1984 Summer Olympics in Los Angeles and ended up winning six medals in four Olympics through 1996.

But her four years on the Bruins’ women’s basketball team as an All-Conference player left her ranked among the career leaders in points, rebounds and games played and helped her win the 1985 Broderick Cup as the nation’s top collegiate female athlete. She red-shirt the 1983-84 season so she could concentrate on her track career and the L.A. Games. But coming back as a senior, her Bruins team twice defeated the Cheryl Miller-led USC squad. She ended up with 1,167 points in her career, which still has her in the Top 20 of the program’s history. She even played in the ABL for Richmond in 1996.

Not well known: Joyner, named the 2001 Alumnus of the Year, was honored in 1998 as one of the 15 greatest UCLA women’s basketball players of all time.

Scott Spiezio, Anaheim Angels infielder (2000 to 2003):

His shot heard around Anaheim came in Game 6 of the 2002 World Series, a three-run homer in the seventh inning that woke the Angels up as they trailed 5-0 against San Francisco on the verge of elimination. What made it more poignant: Giants manager Dusty Baker had just come to the mound to relieve starter Russ Ortiz, handing him the game ball as a souvenir, thinking the series had been wrapped up. The Angels would score three more runs in the eighth, win that game, forcing a Game 7, and their one-and-only title.

Christen Press, Angel City FC striker (2021 to 2025):

Born in L.A. and a standout at Chadwick School in Rancho Palos Verdes, Press was the franchise’s first player signed after scoring 64 goals with 43 assists in 155 games for the U.S. Womens National Team and was part of World Cup wins in ’15 and ’19, plus a bronze in the 2020 Summer Olympics. She marked her 100th NWSL match by scoring a goal in the Angel City’s 1-1 draw at North Carolina. It was her first goal in more than two years as she missed time recovering from an ACL injury that took four surgeries.

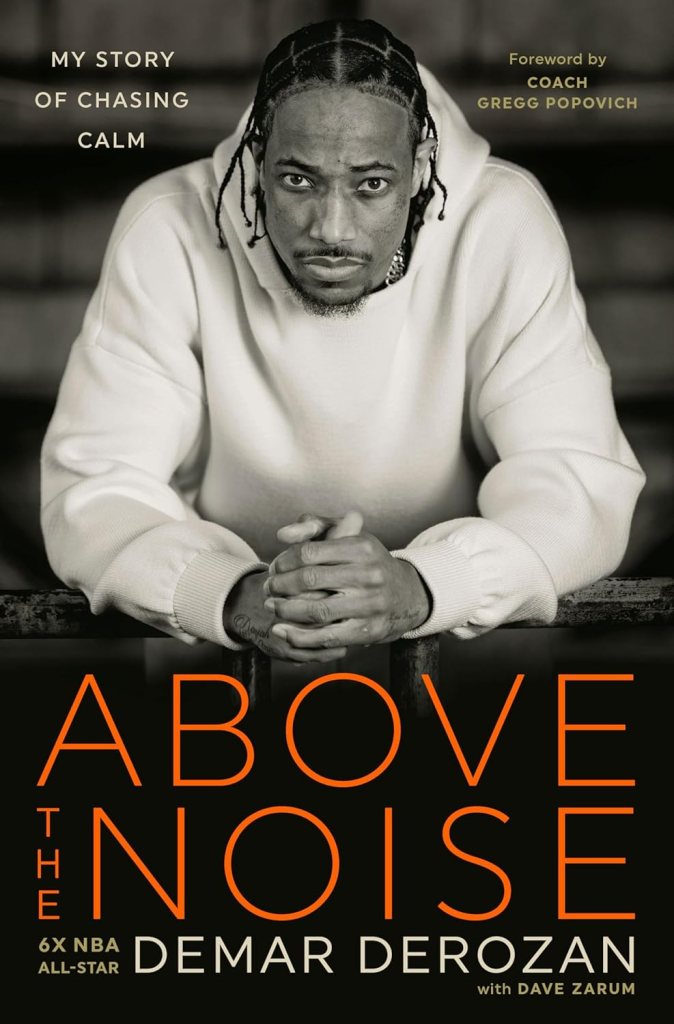

DeMar DeRozan, Compton High basketball (2004-05 to 2007-08):

Averaged 26.1 points and 8.4 rebounds as a freshman, then 29.2 points and 8 rebounds as a senior to become a first-team Parade and McDonald’s All-American. In 2015, the school retired his No. 23. After a season at USC (wearing No. 10, which was retired), DeRozan was a first-round pick by Toronto and four-time NBA All Star. His nine seasons in Toronto turned out to be the franchise’s all-time leading scorer. In his 2024 autobiography, “Above the Noise: My Story of Chasing Calm,” DeRozan writes about the hardship living in poverty, losing friends to gang violence, having relatives from rival gangs. He battled depression and writes about mental illness challenges.

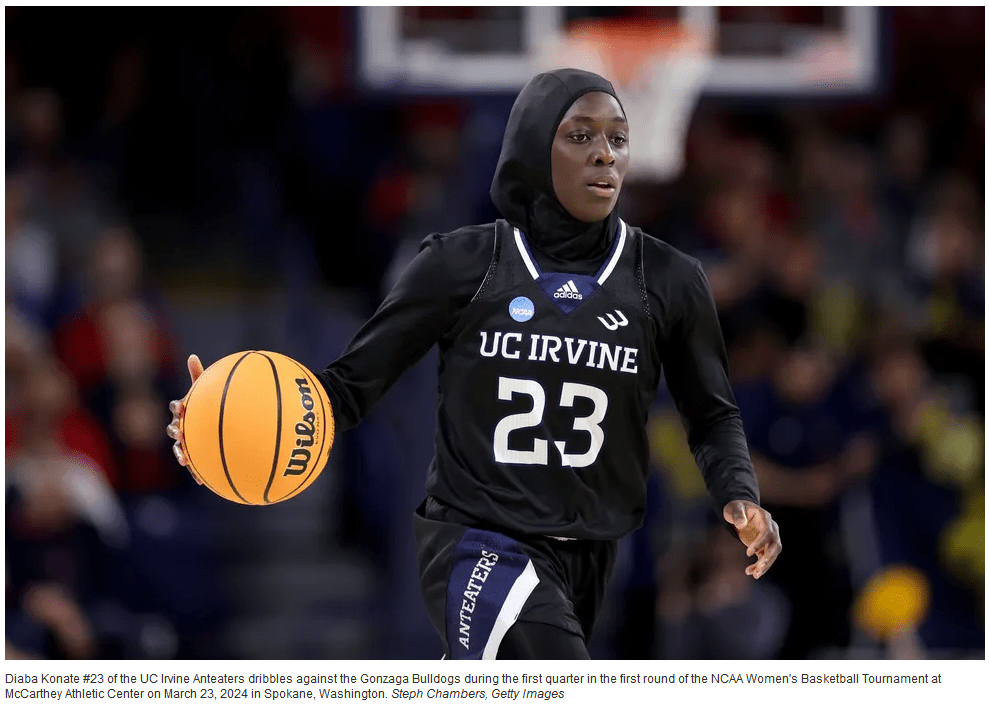

Diaba Konate, UC Irvine women’s basketball (2023-24):

The 5-foot-7 senior guard was named Big West Defensive Player of the Year, led the conference in assists, and was a two-time Big West All-Defensive Team selection. But she was not allowed to play for her native France during the 2024 Summer Olympics, in her hometown of Paris, because she’s a Muslim woman who wears a hijab while playing. A Muslim woman who chooses to cover her head in public, something she started doing in 2021 during the COVID-19 pandemic, said she realize how much comfort and love she felt when she leaned into her faith. “I just wanted to commit more,” she said, “and for me, it was by wearing the hijab.” In early 2022, the French Senate voted to ban hijabs in sports competitions, insisting that “neutrality” is a requirement and stipulating that wearing “conspicuous religious symbols is prohibited.” Konaté acknowledged her selection for France’s Olympic basketball team wasn’t a shoe-in. However, she pointed out that before the hijab ban came into effect she played for the French under-18 national team, with whom she won two silver medals and one gold. “I don’t know if I’m good enough, to be honest. I will never be able to answer that. I’ve never had the opportunity actually to be part of the team.”

One more story for the road:

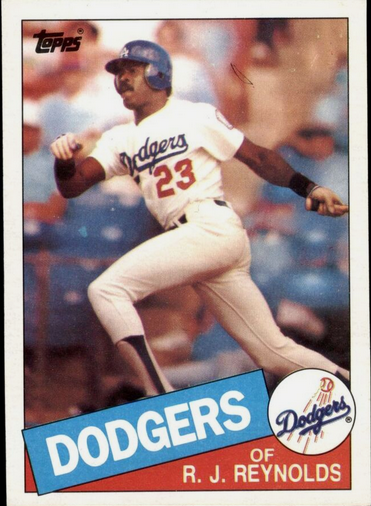

R.J. Reynolds, Los Angeles Dodgers outfielder (1983 to 1985):

His bunt heard around Los Angeles came late on a Sunday afternoon, Sept. 11, ’83, as the shadows crept over the Dodger Stadium infield. The Dodgers were again battling the Atlanta Braves in an important series for the NL West and when the Braves took a 6-3 lead going into the bottom of the ninth, they could have closed the division lead to one game. But the Dodgers loaded the bases. They forced in a run on a walk to Pedro Guerrero. Mike Marshall followed with a game-tying double. After Greg Brock was walked intentionally to set up a force play, Reynolds, batting seventh and starting in center field, had his turn come up. Tommy Lasorda put on the bunt. Reynolds got it down the first baseline, and Braves reliever Gene Garber couldn’t field it in time. All Dodgers fans recall is hearing Vin Scully in the radio booth exclaiming: “Squeeze!” Guerrero came across with the winning run to end the game, 7-6, leading to the Dodgers’ dugout emptying in celebration. The Dodgers would extend their NL West lead to three games — which is the margin they maintained by the end of the season — and Reynolds became a Dodgers’ folk hero, for those who still may have confused him with as a tobacco magnet.

We also have:

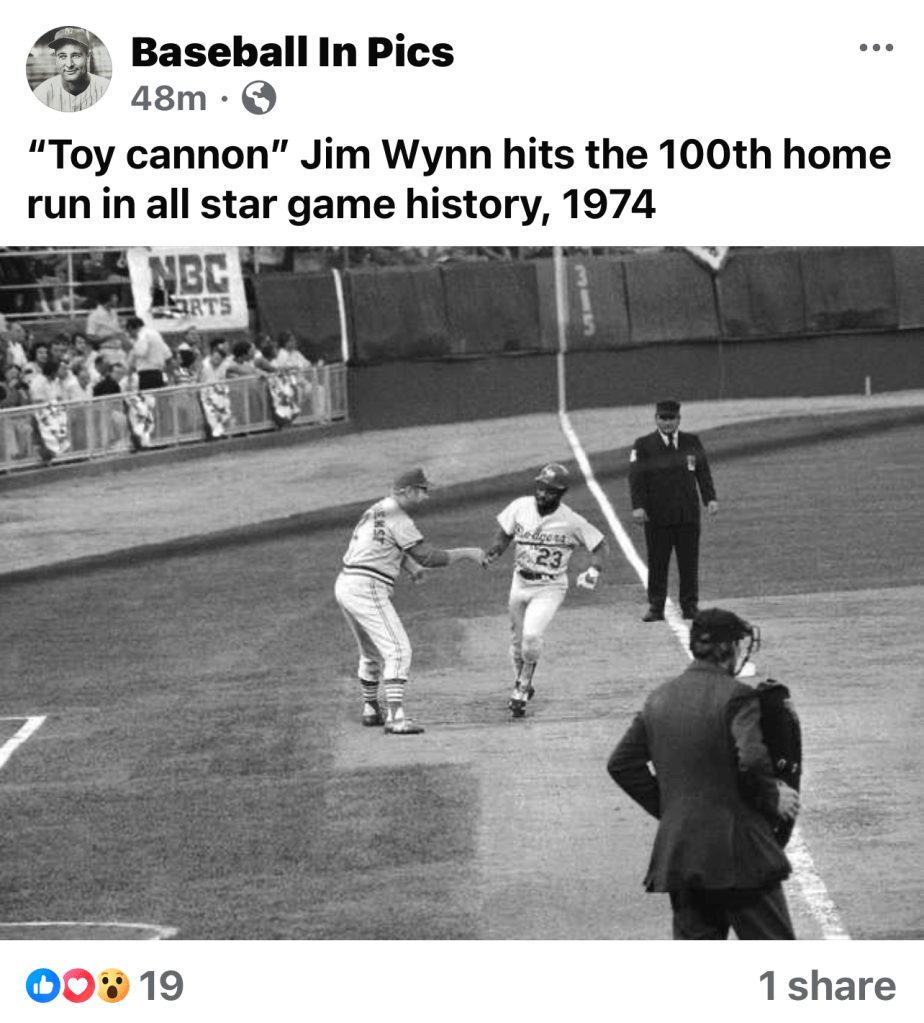

Jimmy Wynn, Los Angeles Dodgers center fielder (1974 to 1975)

Adrian Gonzalez, Los Angeles Dodgers first baseman (2012 to 2017)

Neil Komodoski, Los Angeles Kings defenseman (1973-74 to 1977-78): Also wore No. 24 in 1972-73

Cedric Ceballos, Los Angeles Lakers forward (1994-95 to 1996-97)

Stu Lantz, Los Angeles Lakers guard (1994-95 to 1995-96)

Derek Lowe, Los Angeles Dodgers pitcher (2005 to 2008)

Donnie Edwards, UCLA football linebacker (1992 to 1995)

Don Zimmer, Los Angeles Dodgers shortstop (1958 to 1959, 1963)

Jason Heyward, Los Angeles Dodgers outfielder (2023 to present)

Mark Gubicza, California Angels pitcher (1997)

Zack Greinke, Los Angeles Angels of Anaheim pitcher (2012)

Tim Wallach, California Angels third baseman (1996)

Chris Chambliss, UCLA baseball first baseman (1969)

Dick Williams, California Angels manager (1974 to 1976)

Claude Osteen, Los Angeles Dodgers pitcher (1966 to 1973)

Anyone else worth nominating? What about LeBron James, wearing No. 23 from 2019 to 21, then bringing it back in 2023? There’s an explanation here.

1 thought on “No. 23: Ryan Elmquist”