“I Am Not A Baseball Bozo: Honoring Good Players

who Played on Terrible Teams: 1920 to 1999”

The author:

Chris Williams

The publishing info:

Sunbury Press

148 pages

$14.95

Released Sept. 29, 2021

The links:

The publishers website

The authors website

At Bookshop.org

At Indiebound.org

At Amazon.com

At Powells.com

At Vromans.com

At TheLastBookStoreLA

At PagesABookstore.com

The review in 90 feet or less

Hear us out on this one: If the MLB timekeepers had a real hankering for speeding up games, and maybe could embrace the nostalgia of it all, it would encourage teams to bring back the modified golf carts that deliver relief pitchers from the bullpen to the mound between innings. Sponsored by Lyft.

The guy with the jacket draped over his arm still may feel a bit silly having someone drive him the distance of a short par-3 golf hole. Some teams tried to bring it back in recent years with little cooperation. And we keep hearing folks refer to the oversized baseball caps with wheels as “clown cars.” But that implies there’d be at least a dozen pitchers crammed in, and when the cart stopped, they’d all come tumbling out at some point, honking horns, doing cartwheels and having water shoot out of their lapel flower.

Or, Rodney Dangerfield might suddenly appear.

Baseball, it turns out, already has a nice history of clown-related players, Max Patkin aside. Official bozos, if you are to nickname them a such:

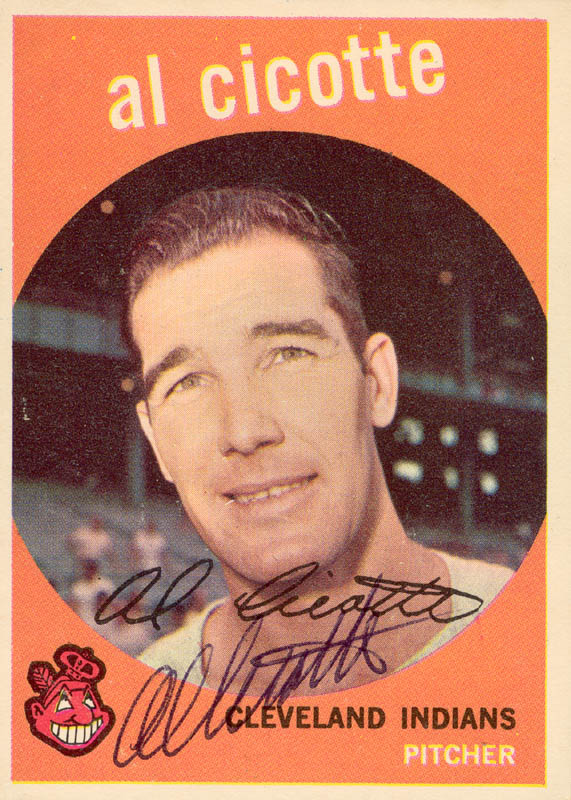

== Bozo Cicotte, at age 32, was an original member of the 1962 expansion Houston Colt .45’s. But that was the finish line of a career that started in American League champion 1957 New York Yankees as a 27-year-old rookie, then took him through the Washington Senators, Detroit Tigers, Cleveland Indians and St. Louis Cardinals for a career mark of 10-13 with a 4.36 ERA in 102 games.

Alva Warren Cicotte by name, the great-nephew of “Black Sox” player Eddie Ciocotte, also pulled off a crafty move in 1977, at the age of 48. In the insurance business after retiring, he signed a one-month deal with the Detroit Tigers that year so he’d be eligible for a Major League Baseball pension. He only lived five more years after that.

== Bozo Jackson pulled together a .354 lifetime average – 23 hits in 65 at bats – but played in only 17 games in four seasons spread over 12 years. Three games in ’33 for the Indianapolis ABC’s of the Negro National League, eight games in ‘38 for the Atlanta Black Crackers of the Negro American League, then three more games in ’43 for the Philadelphia Stars and the last three games in ’45 for the Homestead Grays, both of the Negro National League. The profile of the middle infielder on Seamheads.com also credits him with three games in ’44 for the Atlanta Black Crackers, then an Independent League team.

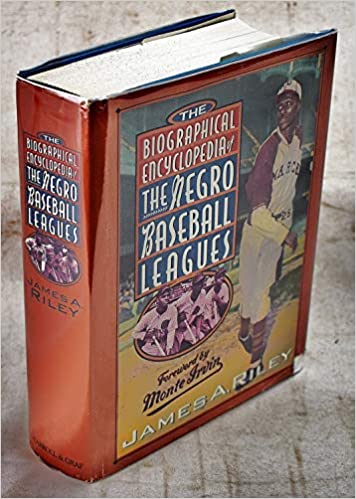

With the way records are kept now, combining Negro Leagues with other pro baseball major leagues, the Baseball-Reference.com site has determined Jackson was the 7,534th player in major league history. The site also notes his full names as James Jackson. Yet his Wikipedia page says it was Bert Jackson. Someday, we hope to see this discrepancy resolved. Maybe it is in 900-plus page version of The Biographical Encyclopedia of the Negro Leagues by James Riley (Carroll & Graf, 1994), one of the more-than 4,000 players from 1872 to 1950 who’ve been documented.

== Bozo Wakabayashi was inducted into the Japanese Baseball Hall of Fame in 1964 — the first Hawaiian honored. He was the MVP twice with the Hanshin Tigers of the war year 1940s. If you really did you homework and wanted someone far more comparable to the Angels’ Shohei Ohtani, consider Henry Tadashi Wakabayashi, a second generation Japanese American whose parents went to Hawaii from Hiroshima, is one of 48 Japanese players with 2,000 career hits and 200 victories on the mound.

Also a member of the Hawaii Sports Hall of Fame, Wakabayashi also has this intriguing sidenote: When the Osaka Tigers played their first season in 1936, jersey numbers were given out in alphabetical order. Wakabayashi was assigned number 4. He didn’t want it — the number because it is considered unlucky in Japan. He was given the first available number instead — 18. His success in the professional leagues made it a custom for a Japanese team’s ace pitcher to be given the number. Daisuke Matasuzaka was given number 18 when he joined the Seibu Lions from high school.

For many reasons, none of these Bozos made it into this collection of players that aims to honor those whose standout seasons on miserable franchises made them stand out like a bright red nose.

Williams, who grew up a Phillies fan in the late ‘60s and early ‘70s, clearly saw plenty of these examples.

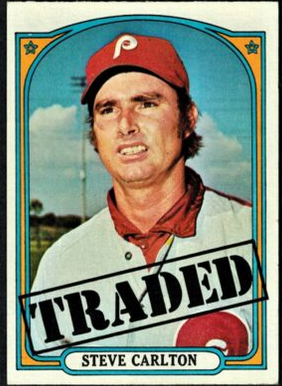

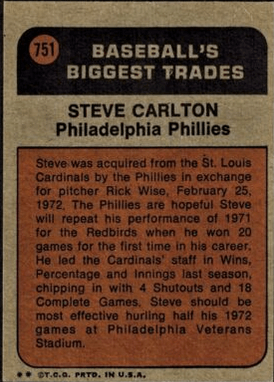

Most famously, future Hall of Fame pitcher Steve Carlton.

After his first seven seasons in St. Louis, Lefty was traded to Philadelphia for Rick Wise in 1972. That season, the 27-year-old Carlton won 27 games with a 1.97 ERA and 310 strikeouts in 41 starts and 346 innings pitched – each category leading the National League, as well as a 12.1 WAR. It got him a unanimous Cy Young Award vote and fifth place in the MVP balloting.

Pretty darn impressive for a ’72 Phillies that otherwise tested positive for awfulness, a 59-97 finish under two managers, one of which came out of the GM office to clean up the mess. They were last in the NL East, 37 ½ games behind the Pittsburgh Pirates.

Carlton’s 27-10 mark was the only one above .500 among 16 pitchers on a staff that had no one else with more than seven wins. The other starters posted win totals of 5, 4, 4 and 2 and lost a combined 48 games. Also, Carlton’s .197 batting average (23 hits, 117 at bats, and a home run in a game he defeated Pittsburgh, 2-0) wasn’t that far off the seasons posted by three of the eight regular position starters.

From our experience, this may be the most dominant performance by an MLB player on a team that had more noticeable cracks than the Liberty Bell.

Yet, it’s not included in this book.

According to Williams’ criteria, someone must be on a team that lost 100 or more games in a season, “for guys who played for the worst-of-the-worst.” Three more losses wouldn’t have made a difference on that ’72 Phillies team. There are other benchmarks that have to do with games played, innings pitched and the player “must have performed at a level noticeably higher, statistically, than his teammates during the year considered.”

Doing the math — carry the one, add an explanation point for astonishment — Carlton was responsible for nearly 50 percent of his team’s victories. He was the sixth pitcher at the time to win 20 or more games for a last-place team, reeling off 15 in a row at one point with eight total shutouts. No pitcher has won more games or thrown more complete games since Carlton did that year, and no pitcher has thrown more innings since ’73.

In all the years the Phillies/Quakers have existed as a National League franchise going back to 1883, they’ve lost 100 or more in 1961, ’45, every season between ’38 and ’42, ’36, ’30, ’28, ’27, ’23, ’21 and ’04. There were 26 additional seasons they lost 90 or more, most recently three straight years from 2015 to ’17. For those teams, we can raise and honor players such as Cy Williams, Cotton Tierney, Dutch Ulrich, Fresco Thompson, Pinky Whitney, Chuck Klein, Lefty O’Doul, Barney Friberg, Dolph Camilli, Kirby Higbe and Johnny Callison.

In 1972, during a strike-interrupted season where most teams only got in about 154 games played, only one team lost 100 or more – the Ted Williams-managed Texas Rangers, in the first year from moving away from Washington. Only a couple of their players are mentioned in the book for their average-at-best performances on that team. The next year, rookie Jeff Burroughs hit 30 homers and drove in 85 for the 105-loss Rangers, and was recognized.

Honk, honk.

Imagine if the Phillies played a full 162 — Carlton could have had a couple more starts in pursuit of 30 wins on a team that surely would have lost 100. We’re doing more math here and … still, it doesn’t add up.

Phillies reliever Mac Scarce explained it best: “Every fourth day we were the best team in baseball. Every other day we were the worst.”

How it goes in the scorebook

Surely, you jest. And don’t call me Shirley.

In our bookkeeping, the Carlton Oversight is a deal breaker as to how we embrace this project.

Love the concept, appreciate all the research that was put into it, enjoy the random asides and comic relief from this member of the Central Pennsylvania chapter of the Society for American Baseball Research. But it can be a tough sell to go on and on about the not-really-all-that-great single-season highlights of players from those Mets or Cubs teams of the 1960s or Padres teams of the 1970s – the worst teams we recall from our baseball upbringing.

Sure, point out Tom Seaver won the NL Rookie of the Year with a 16-win, 2.76 ERA season for the 101-loss ’67 Mets, or Nate Colbert did all kinds of damage for Padres’ teams that could never get up and running after their 1969 debut. And highlight some of those from decades past whose team didn’t allow them their proper due. Eventually, some made the Baseball Hall of Fame. It happens.

But at some point, this runs out of steam, and substance, and we can’t put our finger on just why.

Maybe another thing that bothers us is the fact Johnny Podres is on the cover in a Brooklyn Dodgers baseball card. In his 15 seasons between 1953 and ‘69, Podres never played on a team that lost more than 100 games except in his last year, with San Diego in their ’69 expansion year. A 5-6 record and 4.31 ERA in 17 games hardly deserves mention — and it doesn’t here. Did we miss something somewhere?

Trying not to burst any bubbles here, but maybe it’s another lesson about the perils of self-publishing. Editors and fact checkers are important not just for factual accuracy, but sounding boards to clean things up and secure reader credibility.

It’s a tough act to fill Bozo-sized shoes. If there is a sequel that involves teams from the year 2000 going forward, maybe we can see a revised assessment of things.

You can look it up: More to ponder

== The sports editor of The York Dispatch in York County, Pa., has a piece last June on Williams.

== Also from Williams: “Stealing First: And Other Old-Time Baseball Stories” (Sunbury Press, $14.95, Released in April, 2020)

== One more Bozo reference for the road: Trevor Bell, a first-round draft pick of the Angels in 2005 out of Crescenta Valley High, played three seasons for them from ’09 to ’11. He ended up in Cincinnati for one last fling as a 27-year-old. He may be best remembered as having a tattoo on his left arm of Bozo the Clown – because his grandfather, Bob Bell, played Bozo on WGN-TV in Chicago from 1960 through ‘84.

“He did it for 25 years straight — if I could play baseball for 25 years, that’d be incredible,” Trevor Bell once said. “It’d take him three-and-a-half hours to put his makeup on every day. He’d be up at 3:30 in the morning putting on his makeup and he did it for the kids, and that’s all he did it for. He did it to lighten kids’ days, it was something that was totally selfless. It’s a lost thing nowadays in the arts. It’s still lost in the arts. As far as acting, baseball, it’s keeping those things alive.”