This is the latest post for an ongoing media project — SoCal Sports History 101: The Prime Numbers from 00 to 99 that Uniformly, Uniquely and Unapologetically Reveal The Narrative of Our Region’s Athletic Heritage. Pick a number and highlight an athlete — person, place or thing — most obviously connected to it by fame and fortune, someone who isn’t so obvious, and then take a deeper dive into the most interesting story tied to it. It’s a combination of star power, achievement, longevity, notoriety, and, above all, what makes that athlete so Southern California. Quirkiness and notoriety factor in. And it should open itself to more discussion and debate — which is what sports is best at doing.

The most obvious choices for No. 4:

= Rob Blake: Los Angeles Kings

= Byron Scott: Los Angeles Lakers

= Duke Snider: Los Angeles Dodgers

= Bobby Grich: California Angels

The not-so-obvious choices for No. 4:

= Rodney Anderson: Cal State Fullerton

= Joe McKnight: USC football

= Kevin Pillar: Cal State Dominguez Hills baseball

The most interesting story for No. 4:

Zenyatta: Thoroughbred racehorse (2007 to 2010)

Southern California map pinpoints:

Arcadia (Santa Anita); Inglewood (Hollywood Park)

My moments of Zenyatta came in blindsiding waves.

Driven to tears, on occasion.

Jerry Moss, co-founder of A&M Records, pinned this name on a filly born in 2004 as a tribute to one his clients, the Police. The lads from England with the ultra-hot modern reggae/pop rock sound came out in 1980 with the album, Zenyatta Mondatta. Turns out, who knew both Zenyatta and Mondatta weree apparently invented portmanteau words by band member Stewart Copeland.

“It’s not an attempt to be mysterious, just syllables that sound good together, like the sound of a melody that has no words at all has a meaning,” he explained.

To the Moss family, it was interpreted as a zen-giving experience.

(My one and only attendance at a concert to see the Police during their Synchronicity Tour, when the bill included Berlin, The Fixx and The Thompson Twins, was at the non-concert-friendly Hollywood Park race track in 1983. A year later, the place that gave Inglewood much city pride when it opened in the summer of 1938 hosted the first Breeder’s Cup).

Not a super-keen follower of horse racing, baffled by its wagering mindset that just didn’t compute well with my thinking process, I still enjoyed being assigned to help cover big events. The 2009 Breeders’ Cup at Santa Anita Park was one of them, yet my focus was far more on those who showed up and were involved with all the money passing hands around me.

As the sun was setting on the majestic Santa Anita Park, a thoroughbred in pink and turquoise silks named Zenyatta, ridden by the master Mike Smith, would stick with me decades later as the most blindsiding, exhilarating, most Southern-California sports moment I ever witnessed.

A horse that appropriately ran away with the Breeders’ Cup Ladies’ Classic a year earlier dared to be entered in a field against the world’s most worthy males, of any age, size and nationality. This was a true world championship.

Reluctantly, flashing the No. 4, it became a forgone conclusion in her mind. Maybe. We’ll never be able to ask her.

Such a Garbo move.

The story

As the capper to perfect 5-0 season, and trying to extend a 14-o career record based mostly on running with her own gender, Zenyata pulled off an unlikely, historic victory in the Breeders’ Cup Classic against an all-male field with a final stretch run for the ages.

Coming from dead last, nearly DQ’d with another horse, 15 lengths back at one point in her first 1 1/4 mile-length race, seven lengths back as the pack headed into the stretch, she won. And we’ll have Trevor Denman’s goose-bump-raising call in our heads — “Un-be-lieve-able!” — to match the live race we not only witnessed but were literally running down the concourse aisle to keep up with finish.

The one thing that remains also seared in my memory is, as spectators cheered and the grandstands shook, many in disbelief, I saw a woman in full classic horse-racing attire – large hat, frilly dress, all dolled up – trying to explain to her very young and equally dressed up daughter why everyone around them was acting somewhat insane.

“A girl … just beat … all the boys!” the mom screamed.

And then Bo Derek presented the winner’s trophy to the Moss family.

The most compelling recap I can offer is from in the New York Times on Nov. 7, 2009, under the headline “A Classic Ending to Zenyata’s Perfect Season.” Joe Drape wrote this:

“Zenyatta is a headstrong girl, and a big one, too. So when she balked entering the starting gate here Saturday, a gasp rippled through the grandstand. As she was awaiting the start of the Breeders’ Cup Classic, against the best male horses in the world at a distance she had never run, did she suddenly not want to race?

“Mike Smith, her jockey, smooched in, and she stood quiet. But outside, in Post 12, Quality Road was acting up. He bucked and spun, then broke through the gate. Finally he was scratched, and Zenyatta and the 11 other horses were backed out and their riders were asked to dismount.

“This was no way to start a mile-and-a-quarter race with a $5 million purse, a perfect 13-0 record and the bursting hearts of Zenyatta’s devoted followers on the line. When the gates finally popped open, Zenyatta stood there alone. It would be the last time she would look as if she did not belong with the best turf horses in North America, a couple of monsters from Europe, and the Kentucky Derby and Belmont Stakes champions.

“In fact, when it mattered most, in the lane, surrounded by a thundering herd, Zenyatta found another gear –no, another engine –and rolled from the rail to the widest path of all. She was large and in charge, and bounded down the Santa Anita Park racetrack as if she were on a trampoline.

“The Triple Crown winners got left first. Mine That Bird and Summer Bird, see you later. Rip Van Winkle and Twice Over, go back to Europe. The only horse left was Gio Ponti in the middle of the track. He is a salty colt who has won four Grade I races on the turf, and runs like a horse who loves what he does.

“He was running another big race now, but his jockey, Ramon Dominguez, was working hard with his hands and whip to keep it that way. Smith, on the other hand, was a passenger on Zenyatta. The only thing he was beating back was a smile.

“ ‘I believe if there was another horse ahead of him,’ Smith said of Gio Ponti, ‘she would have caught him, too. She still had run left.’

“The crowd of 58,000 was on its feet, and its full-throated roar made it clear that it, too, thought Zenyatta could keep going. In the grandstand, Jerry and Ann Moss, her owners, had tears welling, as did her trainer, John Shirreffs. The chart said Zenyatta won by a length and covered the mile and a quarter in 2:00.62.”

Just call her the greatest mare of all time and that should tie it all up.

The context

If the sport of horse racing was said to be on life support at a time when there was a strange push back to sports gambling and a keen focus on animal rights, and perhaps a disconnect from those who had money to own these things and those without the means to regularly wager on them with much success, Zenyatta’s arrival at that moment in time may not have rejuvenated the spirit of how we looked at this all, but she wasn’t going to leave it for dead as long as she was around.

As L.A. Daily News columnist Kevin Modesti wrote at the time: “Biggest Santa Anita cheers since John Henry, said people who were around 25 years ago,” a reference to the legendary two-time Eclipse Award winning thoroughbred who ran a ridiculous 83 times in an eight-year career, winning 39 races, including the 1981 and ’82 Santa Anita Handicap.

If the thoroughbred horse racing’s Triple Crown hype and glamor was to be found based in Kentucky, Maryland and New York, Southern California’s contribution — much like Major League Baseball’s eventual expansion from East to West — relied very much on the success of this 320-acre race track at the foot of the majestic San Gabriel Mountains that opened during the Depression in 1934, four years before Hollywood Park.

Seabiscuit, who won the first Hollywood Gold Cup in ’38, ran his last race in the 1940 Santa Anita Handicap with 68,000 watching to become the richest horse of all time (wearing No. 1) and an immediate Hollywood movie idol.

Santa Anita’s history is a mixed bag.

The Los Angeles Turf Club opened the track on Christmas Day in 1934, making it the first formally-established racetrack in California. Its hey day was a sign of the Hollywood elite, from Cary Grant, Clark Gable, Bing Crosby, Al Jolson, Betty Grable and Lana Turner — either as attendees or stock holders. It would be the backdrop of countless movie and TV shoots.

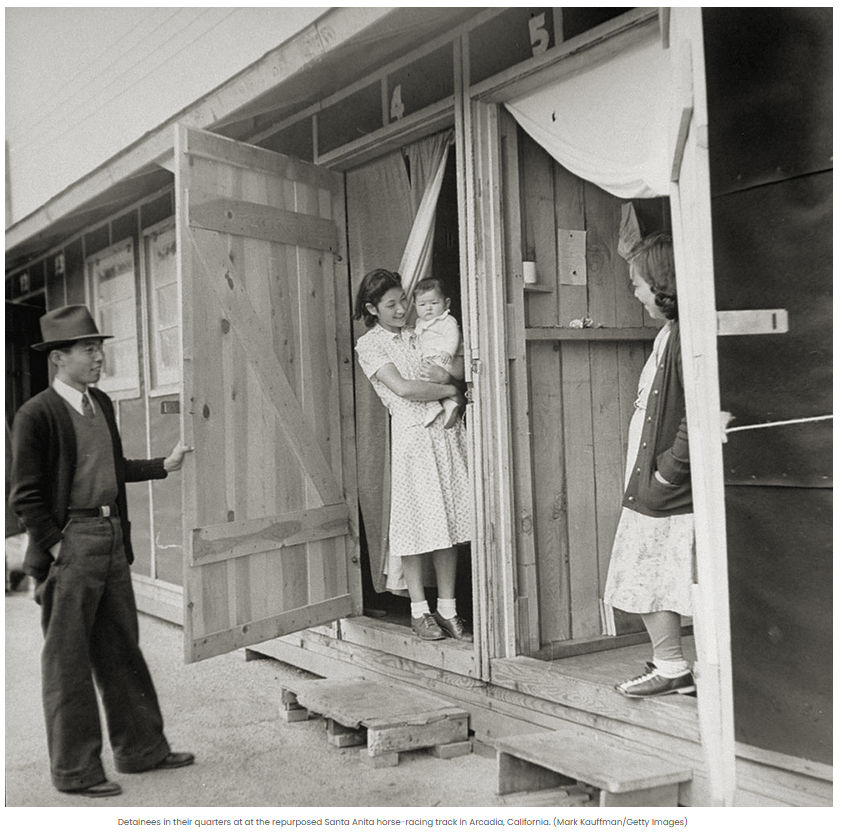

It closed for seven months during World War II in 1942 to serve as a Japanese American internment camp, and 18,000 people from Los Angeles County were forced to live in the horse stables and barracks constructed. It was officially called the Santa Anita Assembly Area by President Franklin D. Roosevent’s Executive Order 9066. Santa Anita was turned over to the Wartime Civilian Control Administration. Six mess halls fed 3,000 daily at 33 cents per person. Showers were limited. Jobs created included a camouflage net factor as well as a school and a hospital. Actor George Takei, then a young boy, was among them.

In 2000, it was added to America’s “Most Endangered Historic Places” list, threatened by developer’s plans for the land. It was listed in the National Register of Historic Places in 2006.

In 2025, it served as a relief support venue for victims of the massive wildfires that claimed thousands of homes in Brentwood, Malibu and Altadena. Southern California Edison also used the site as a basecamp to restore power to those affected.

The track may have not returned to any sort of prominence until John Henry’s 1980s era of victories. It hosted the equestrian events at the 1984 Olympics. It then had the third Breeders’ Cup World Championships in 1986,and has been home to it nine times through 2023.

The Breeders’ Cup at Santa Anita provided all sorts of historic moments over the years. Another of our personal thrills was seeing Jim Rome, the So Cal-bred sports-talk show host, own a horse called Mizdirection that won the 2012 and ’13 Breeders’ Cup Turf Sprint — another instance of a gray mare winning against a field of males. Rome was then co-owner of Breeders’ Cup Classic favorite and then-undefeated Shared Belief in the 2014 race.

But arguably there was no more spectacular bidding sporting moment than what Zenyatta provided in 2009. This was a genuine SoCal sports history moment.

Again, Modesti wrote on that brisk fall afternoon — under a headline that screamed ‘YATTA, ‘YATTA, ‘YATTA! — people were carrying signs and T-shirts reading things like: “Hillary Who? Zenyatta: First Female President, 2012,” or “Girl Power.”

“How do you know Zenyatta is a once-in-a-lifetime racehorse?” Modesti asked. “You watch her effect on everyday people.”

And she tried to replicate it a year later, across the country in another thoroughbred haven.

In 2010, she was on track to go back to the Breeders’ Cup Classic, this time held in Louisville. Still perfect with a 19-0 record, she made her final appearance at Hollywood Park in October of 2010, and I wrote from the heart about my blindsided attraction to this mare-thee-well as she won the Lady’s Secret Stakes at Oak Tree.

A month later, Zenyatta lost her first race after 19 wins when Blame beat her by a head, handing the 6-year-old mare her first defeat.

Can’t blame her for calling it a career after that.

The legacy

She left Southern California for breeding, and we’ve not seen or heard much of her since. Four years later, Hollywood Park closed down. Santa Anita has been in the news mostly for trying to figure out why so many horses keep getting injured and are forced to be put down.

The fall of ’09 is what we had with Zenyatta, and no one can take that away. No justification necessary in inducting her into the National Horse Racing Museum Hall of Fame in 2016.

As Lenny Schulman wrote for Bloodhorse magazine in 2013: “The mare had more human-like qualities than any horse in memory. She pranced and danced and pawed at the ground in the paddock, signifying she knew it was time to go out and perform. She had already been the center of dozens of charity events as her equipment was auctioned off to raise money for those in need while other donors paid money to come to her Hollywood Park barn and have a meal in her presence.

“Then there was the matter of her running style, loping along behind her field before igniting a sustained drive, employing huge strides to inexorably close the distance between herself and her targets. And there was her giant physical stature of more than 17 hands, the machinery from which those great strides sprung.

“For those of us who watch sports to see those rare athletes that are poetry in motion, Zenyatta running represented the same Godsend as watching Michael Jordan drive to the basket or Willie Mays sprint around the bases or Jim Brown shed a tackler and cut up field.”

On the last day of 2023, Los Angeles Times retired sports editor Bill Dwyre posted a look at Zenyatta to mark her 20th birthday — she was actually born April 1, 2004, but all thoroughbreds are made a year older on Jan. 1. Amidst Dwyre’s best phrase-turning moments are when he recounted the 2009 and ’10 Breeder’s Cup Classics as “two of the most famous scenes in the history of the sport.”

He wrote about Zenyatta coming up on the outside to win the 2009 race:

“Creaky old Santa Anita was about to have a resurrection. The Great Race Place would be great again, at least for a day. … The word ‘crescendo’ was crated for moments like this. The noise soared like a jet airplane on takeoff. Seldom have 58,000 people, uniformly this vocally delighted and expressive, produced such an ear-piercing sound. … Handkerchiefs waved, grown men cried and fathers and mothers put their children on their shoulders so they could get a better look at this wonder of the thoroughbred world.”

Yes, that’s just how we’ll remember it as well.

Who else wore No. 4 in SoCal sports history?

Make a case for:

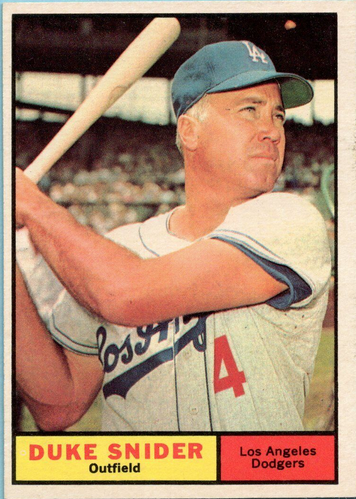

Duke Snider, Los Angeles Dodgers outfielder (1958 to 1962):

Best known: The franchise rightfully retired his number 4 for all he accomplished in Brooklyn. The Compton native got to take a victory lap when the Dodgers moved to Southern California, and Snider stuck around until the first year at Dodger Stadium, a feeling as if the circle of Dodger life had been completed — one of just a handful to have played at Ebbets Field, the L.A. Coliseum and Dodger Stadium. All these years later, Snider remains the franchise leader in home runs (389), RBI (1,271) and extra-base hits (814) — as well as 1,123 strike outs. He is the only player to hit four home runs (or more) in two different World Series (1952 and ’55). On Aug. 26, 1960, the Dodgers hosted a “Duke Snider Night” at the L.A. Coliseum for their seven-time NL All Star, as his wife, Beverly, waved to the crowd from a new Corvette, while his children enjoyed having their own smaller version of the cars. Snider was 35 in ’63 when he was purchased by the New York Mets as a good-will gesture. The Mets first gave him No. 11, then finally had him wear his famous No. 4 after it had been worn the first 72 games by Charlie Neal, Snider’s former Dodgers’ teammate, who was traded to Cincinnati in July. A year later, the San Francisco Giants purchased his contract and gave Snider No. 28 — the franchise retired No. 4 for Mel Ott.

Not well remembered: It was a bit odd that the National Baseball Hall of Fame’s Class of 1980 inductee had his No. 4 retired by Dodgers after a big ceremony in 1972 to hang up Nos. 42, 32 and 39 for Jackie Robinson, Sandy Koufax and Roy Campanella. The wait was long enough to where center fielder Bill North wore No. 4 in 1978.

Rob Blake, Los Angeles Kings defenseman (1989-90 to 2000-2001 and 2006-07 to 2007-08):

Best known: The seven-time All Star and 1997-98 Norris Trophy winner had his number retired by the Kings in 2015, a year after he was inducted into the Hockey Hall of Fame. In 1995-96, as Blake suffered an injury that restricted him to six games, he was still named the Kings’ captain after Wayne Gretzky was traded to the St. Louis. After five seasons in Colorado, Blake returned to L.A. and became captain again before the 2007-08 season. Playing 14 of his 20 NHL seasons as a King, he scored 161 of his 24o goals and had 333 of his 537 assists with the franchise in 805 games. After Blake became the Kings’ vice president and general manager in 2017, he lasted there until May of 2025.

Bobby Grich, California Angels second baseman (1977 to 1986):

Best known: In 10 seasons with the Angels, Grich made three AL All Star games and was a key part of the teams that made it to the AL Championship Series in 1979, ’82 and ’86. The first inductee into the California/Los Angeles Angels Hall of Fame in 1989, Grich, a first-round draft pick out of Long Beach Wilson High by Baltimore and in the big leagues by age 21 amassing four Gold Gloves, also has had a case for Cooperstown based on his defense, power at his position, a perennial AL MVP candidate with the Angels and a career WAR of 71.1.

Not well remembered: In the strike-interrupted 1981 season, Grich’s 22 homers in 100 games tied for the AL lead, and he led the AL in slugging percentage, winning a Silver Slugger Award.

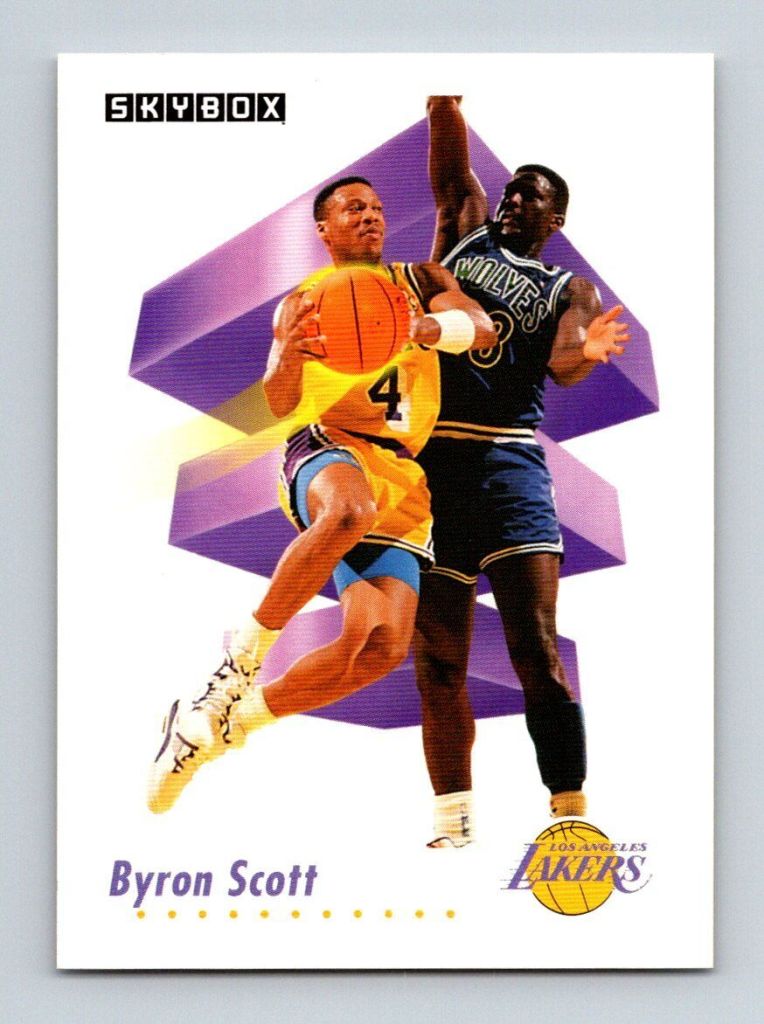

Byron Scott, Los Angeles Lakers guard (1983-84 to 1991-92, and 1996-97):

Best known: The Morningside High of Inglewood standout grew up down the street from the Forum and, after drafted No. 4 overall by San Diego, he was traded to the Lakers for star guard Norm Nixon and became a vital part of the Showtime 1980s, playing on three championship teams. A long-range shooter who also had remarkable leaping skills and defensive prowess, Scott led the Lakers in scoring with a career-best 21.7 points in 1987-88. Scott’s contribution to the Lakers in a return for the 1996-97 season was as a mentor to 18-year-old Kobe Bryant — whom Scott would then coach as the Lakers hired him after Mike D’Antoni from 2014 to 2016, and posted the worst record (38-126) of any coach in franchise history who was there more than two seasons.

Trevor Ariza, Westchester High basketball (2003), UCLA basketball (2003-04): California’s Mr. Basketball as a high school senior spent just one year at UCLA (11.6 points, 8.4 assists) before starting on an 18-season NBA career, which included two stops as a defensive specialist with the Los Angeles Lakers (2007-08 to 2008-09, wearing No. 3, and 2021-22, wearing No. 1).

Penny Toller, Long Beach State basketball guard (1986 to 1989): Considered one of the best ever collegiate players under future Hall of Fame coach Joan Bonvincini, Toller was inducted into the Long Beach State Athletic Hall of Fame in 1995 and had her No. 4 retired in 2007. During her career Long Beach State made it to the Final Four in 1987 and ’88 and she set records for career assists and career free-throws.

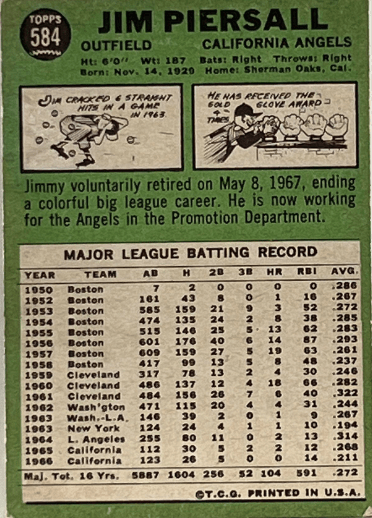

Jimmy Piersall, Los Angeles/California Angels outfielder (1963 to 1967): He only played for five teams in 18 seasons, and the Angels for his last five. Every team should have had a turn having him on its roster. What was there to fear? (We’ve purposely flipped his final Topps card over, because, well, that felt appropriate).

Tony Conigliaro, California Angels outfielder (1971): At age 26, trying to recover from a horrible beaning that took place in Boston in 1967 by Angels pitcher Jack Hamilton, he ended up playing in Anaheim, hitting four homers and driving in 15 in 74 games. Read his 1970 book, “Seeing It Through: The Story of a Comback.”

Evan Mobley, USC men’s basketball (2020-21): The 7-foot freshman from Rancho Christian High in Murietta lasted one COVID season, was named Pac-12 Player of the Year, Freshman of the Year, Defensive Player of the Year and second team All-American for leading the Pac-12 with 8.4 rebounds and 2.9 blocks a game to go with 16.4 points a game. In the conference tournament quarterfinals, Mobley had a career-best 26 points with nine rebounds and five blocks against Utah. His father, Eric, had been an assistant at USC since 2018 and this set the team up for an Elite Eight run before a loss to Gonzaga ended their season at 25-8. Mobley was the No. 3 overall pick in the 2021 NBA Draft by Cleveland.

Have you heard this one:

Rodney Anderson, Cal State Fullerton basketball guard (1999-2000):

Anderson, who grew up in South L.A. and starred at Washington High, played just one season as a freshman with the Titans, starting one game, averaging 3.4 points in 24 contests. Some 25 years later, his LinkedIn account identifies him as Dr. Rodney Anderson, Assistant Director for the Male Success Initiative at CSF. Anderson exists with an elaborate electronic chair that transports him to his shower, bathroom and gym, controlled by futuristic computer named Alexander who responds to his commands. In 2000, gang member’s bullets ended his basketball career in a case of mistaken identity. His framed jersey is next to him at the home he shares with wife Monique courtesy of ABC’s “Extreme Makeover: Home Edition,” Here’s more of the story. And one right after his injury. was appointed an athletics academic counselor at CSF in 2008, earning his master’s degree in counseling that year, and earned his bachelor’s degree in human services in 2005.

Kevin Pillar, Cal State Dominguez Hills baseball center fielder (2008 to 2011):

Born in Tarzana, Pillar went from Chaminade High in West Hills as an All-CIF player hitting .463 as a senior to CSUDH. In 2010, Pillar set an NCAA Division-II record by hitting in 54 straight games, from Feb. 8 to May 8, and was first-team all CCAA with a .379 average. Toronto waited until the 32nd round — which doesn’t even exist any more — before drafting Pillar. In 13 seasons from 2013 to 2025 — the first seven with Toronto, and including 2022 with the Dodgers (wearing No. 11) and 2024 with the Angels (wearing No. 12) — Pillar had a career WAR of 16.1. “The things that I’m most proud of is, first of all, that I made it,” Pillar told MLB.com in 2025. “I was drafted in the 32nd round, I was the 979th overall pick. I played at a Division II school. The fact that I even made it was an accomplishment. The fact that I survived 10 years and I’m part of that small fraternity is an amazing accomplishment.” He added that It helped growing up listening to Vin Scully call Dodgers games. “Vin Scully talked to me in my household. Growing up, he made me love baseball,” Pillar said. “He was part of the reason I felt like I could be a Major League Baseball player, because It helped that Pillar was a baseball fan, spending his evenings as a child listening to Vin Scully call Dodgers games. “Vin Scully talked to me in my household. Growing up, he made me love baseball,” Pillar said. “He was part of the reason I felt like I could be a Major League Baseball player, because he would talk about the Major League Baseball players like they were no different than me. … There was always a part of me that he made believe that I could do it because of the way he talked about baseball players. It was kids that grew up in a household just like mine, played high school baseball just like I did, had other interests and hobbies. It never left me, being a fan, because I don’t think I was ever really expected to get to where I got to.”

We also have:

Joe McKnight, USC football running back (2007 to 2009)

Luke Walton, Los Angeles Lakers forward (2003-04 to 2011)

Ron Harper, Los Angeles Lakers guard (1999-2000 to 2000-01)

Alex Caruso, Los Angeles Lakers guard (2017-18 to 2020-21)

Greg Zuerlein, Los Angeles Rams punter (2018 to 2019, also in St. Louis from 2012 to 2017)

Aaron Afflalo, UCLA basketball guard (2004-05 to 2006-07)

Trevor Wilson, UCLA basetball guard (1986-07 to 1989-90)

Dave Hutchison, Los Angeles Kings defenseman (1974-75 to 1977-78)

Omar Gonzalez, Los Angeles Galaxy defender (2008 to 2015)

Gene Mauch, California Angels manager (1981 to 1982, 1985 to 1987)

Doug Rader, California Angels manager (1989 to 1991)

Anyone else worth nominating?

1 thought on “No. 4: Zenyatta”