This is the latest post for an ongoing media project — SoCal Sports History 101: The Prime Numbers from 00 to 99 that Uniformly, Uniquely and Unapologetically Reveal The Narrative of Our Region’s Athletic Heritage. Pick a number and highlight an athlete — person, place or thing — most obviously connected to it by fame and fortune, someone who isn’t so obvious, and then take a deeper dive into the most interesting story tied to it. It’s a combination of star power, achievement, longevity, notoriety, and, above all, what makes that athlete so Southern California. Quirkiness and notoriety factor in. And it should open itself to more discussion and debate — which is what sports is best at doing.

The most obvious choices for No. 51:

= Randy Cross: UCLA football

= Chip Banks: USC football

= Lauren Betts: UCLA women’s basketball

The not-so obvious choices for No. 51:

= Randy Johnson: USC baseball

= Jonathan Broxton: Los Angeles Dodgers

= Terry Forster: Los Angeles Dodgers

The most interesting story for No. 51:

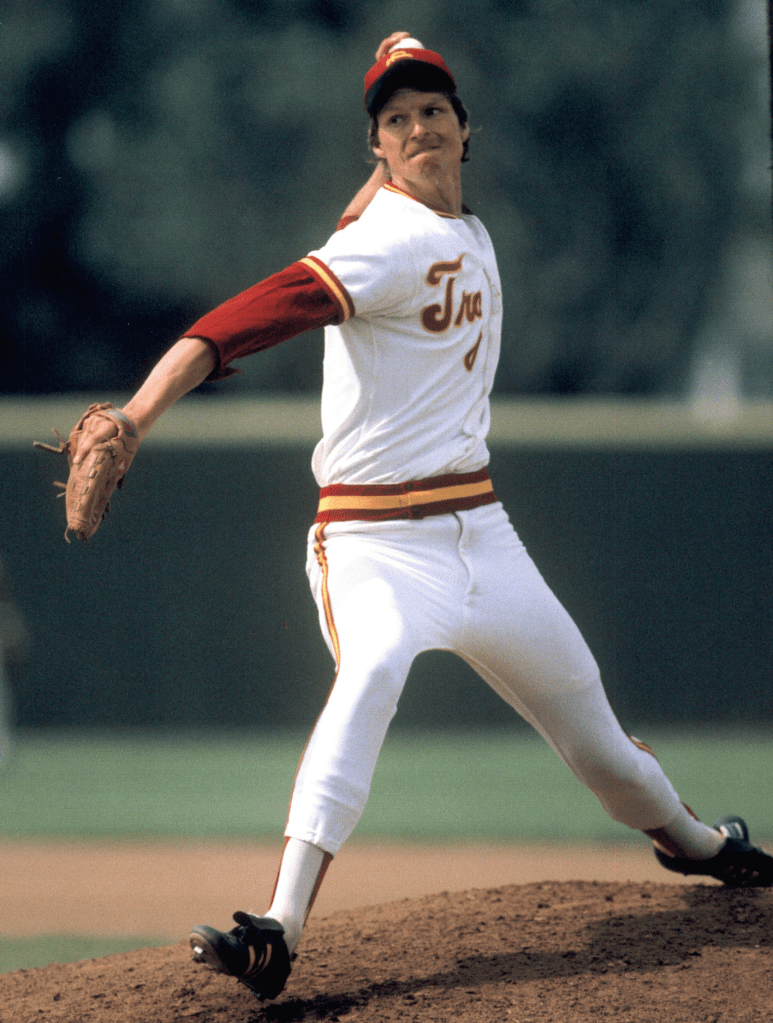

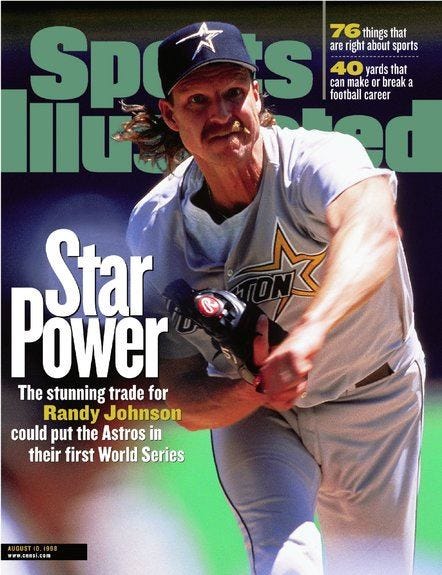

Randy Johnson: USC baseball pitcher (1983 to 1985)

Southern California map pinpoints:

= Downtown L.A. (USC, Dodger Stadium)

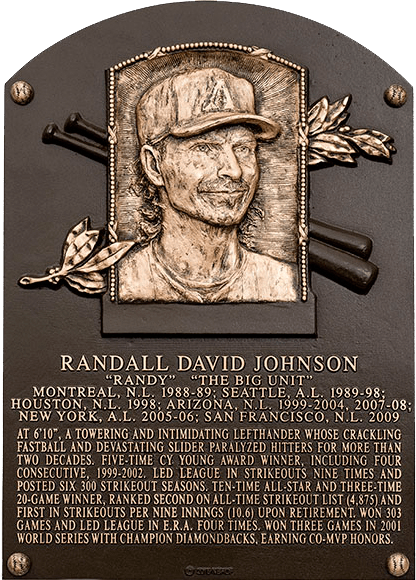

Randy Johnson’s 2015 National Baseball Hall of Fame induction, which came with 97.3 percent of the 549 ballots in agreement, had everything to do with five Cy Young Awards (including four in a row at the turn of the century), second all-time in strikeouts with 4,875 (behind Nolan Ryan’s 5,714), four ERA titles, 100 complete games, a no-hitter (1990) and a perfect game (2004), 10 All-Star teams, and the fifth left-hander in MLB history to exceed 300 wins.

It’s all up there on the bronze with all capital letters crammed into it, describing his “crackling” fastball and “devastating” slider over 22 seasons with six teams.

The plaque had nothing to do with the three years he spent at USC throwing a baseball in the general vicinity of opposing hitters, trying to figure how to make his 6-foot-10 collapsable body work as a one unit.

“The Big Unit” didn’t have a big-man-on-campus status.

“The Human Tripod,” a name that could have been pinned on him when he was representing the Daily Trojan newspaper as a photographer, had bigger things to focus on.

Born in Walnut Creek on the East Bay region of the San Francisco Bay area, Johnson, as a 7-year-old in Granada Little League in Livermore, didn’t find baseball as fun as riding skateboards and motocross bikes, playing soccer, basketball and tennis, and taking up the drums.

“A normal kid,” he said.

At Livermore High, Johnson felt more at home on the basketball court — but he was cut from the team as a junior when he could not complete the mandatory six-minute mile run. He came back as a senior and led the East Bay Athletic League in scoring with a 20.1 points per game average.

“Shooting a basketball was easy because I was actually taking advantage of my height,” he said. “But growing that much in a short period of time made it difficult playing baseball.”

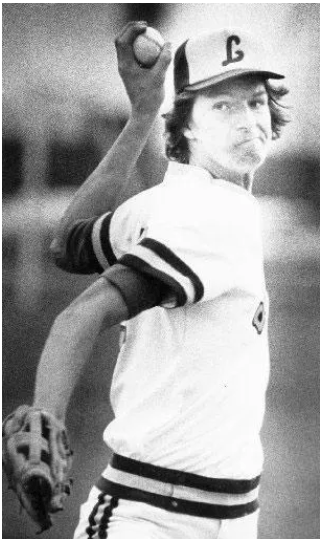

As for baseball, the 6-foot-9 Johnson drew the attention of the scouts for his ability to strike batters out — 121 in less than 66 innings in his senior year, capped off with a perfect game in his last contest against Dublin High. Johnson’s combined record at Livermore in 1981 and ’82 was just 7-11, but it included six defeats in which he allowed a total of two earned runs. He had 227 strike outs in 133 1/3 innings with a 1.73 ERA that sat at 1.15 as a senior.

One of the baseball scouts who sized him up was Justin Dedeaux, whose father Rod was the coach at USC. Dedeaux was sold on Johnson the first time he saw him.

“They had all this ground fog that day, and this head just came out of the fog. I was thinking, ‘Omigod!’ ” Dedeaux recalled. “Mechanically, it was going to take some work. But he could bring it.”

Atlanta was brave enough to make Johnson its fourth-round pick in the 1982 MLB Draft, 89th overall. He turned down an offer of $48,000.

Johnson figured a USC education would become more bankable, and he thought he could play both baseball and basketball for the Trojans.

In winter-league play before his 1983 USC freshman year, Johnson struck out 19 batters in 19 innings and had a 2.37 ERA. He then struck out 34 and gave up 32 walks in 47 innings to post a 5-0 record despite a 5.17 ERA, pitching mostly in relief.

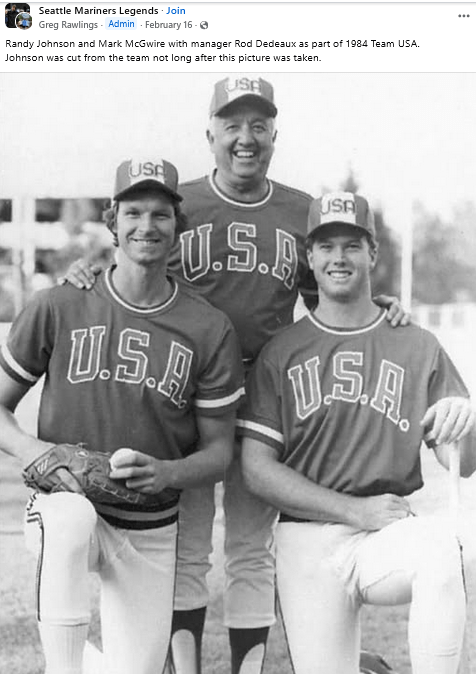

Overlapping a career with eventual college player of the year Mark McGwire, who also himself pitched as a sophomore, Johnson went 5-3 in 1984 with a 3.35 ERA in a team-high 26 games — 12 starts, three saves, 73 strike outs and 52 walks in 78 innings.

The previous December, USC coach Rod Dedeaux got Johnson into a pool of players considered for the U.S. baseball roster as a demonstration sport in the 1984 Los Angeles Summer Olympics. Johnson made it to the round of 44 players but didn’t make the first cut; McGwire moved on with Dedeaux as the coach, winning gold

By his junior year, Johnson decided to just focus on baseball, having not made it quite gaining the attention of Stan Morrison’s basketball team.

For ’85, Johnson racked up 99 strikeouts in 118 1/3 innings — but also allowed a school-record 104 walks, double his previous season. His fastball was in the 90-mph range, and he was rated the 12th best college draft prospect and fourth best pitcher according to scouting directors talking to Baseball American, despite a 6-8 record and 5.30 ERA in 18 starts for Dedeaux’s 22-44 squad. That would be the Trojans’ poorest team record in its history, capped off by being swept by UCLA in the final three games of the season.

“People read about me and say, ‘Who is this 6-10 guy?’ Then they come out to games to see for themselves,” Johnson told the Los Angeles Times about what he was doing at the time.

Johnson thought his mechanics were good, but he lacked consistency. He pumped himself up with talking to the ball, and running over to his infielders to shout encouragement.

Some were already comparing him to another goofy USC left-handed named Bill “Spaceman” Lee.

“When I go out there and don’t do my antics, the team is laid back,” Johnson reasoned. “But when I go through my routine, they’re more alert and they play better for me. When I’m not doing it, (third baseman) Dan Henley will usually come and tell me to get pumped up.”

Dedeaux told the story about going to the mound to talk to the freshman Johnson as they were playing a game at Stanford.

“The leadoff hitter tripled, so I went out to tell him to pitch from a windup, not a stretch,” said Dedeaux. “He told me he had to pitch from a stretch because of the runner at first. I told him there wasn’t anyone on first. He turned and pointed … at the Stanford first-base coach.

“Wouldn’t it have been something if he threw over there, trying to pick him off?”

USC assistant baseball coach Keith Brown defended Johnson: “Randy’s enthusiasm is genuine. He means it when he congratulates players after good fielding plays. He’s glad the play was made. What he does is beneficial, too. We play better defense behind him.”

Johnson’s three seasons at USC produced a 16-12 record, a 4.66 ERA in 67 appearances, five saves, 206 strikeouts and 188 walks in 243 1/3 innings and a 4.66 ERA. He told the East Bay Times that after he was done at USC, he “didn’t learn as much about pitching as I thought I would.”

Still …

Johnson’s induction into the USC Athletics Hall of Fame came in 2012.

And …

In 2016, Johnson would be part of the Pac-12’s All-Century team — other USC players included first baseman McGwire (1982 to ’84), second baseman Bret Boone (1988 to ’90), outfielder Fred Lynn (1971 to ’73), pitcher Mark Prior (2000 to ’01) and pitcher Tom Seaver (1965).

And then …

In 2020, a fan vote taken by the Trojans athletic program announced Johnson as their “Favorite Baseball Player in USC History.” That’s pretty selective memory for a program that includes McGwire (voted second), Lynn (voted third), Tom Seaver (fourth, despite just one year) and Jeff Clement (a catcher who won the Johnny Bench Award in ’05). The school had a bobblehead giveaway in his honor.

Again, with those pedestrian college-level stats? Memories can play trick on you.

Short story tall, it’s mostly because of what happened later.

The other part of that story

We interrupt this yarn for an excerpt from a column I wrote about Johnson in the Los Angeles Daily News in 2015. Note on a team photo taken of the Daily Trojan flag football squad prior to its annual “Blood Bowl” game against the Daily Bruin in 1982.

Johnson was the tall guy in the back row trying to look unassuming. I was in the front row wearing a plastic Trojan helmet, trying to look necessary.

What I pounded out on the keyboard with glee:

The rest of the journalists-wannabes from the USC Daily Trojan newspaper staff filling out that frame … were only certain after this particular autumn day that we would never see Johnson’s bust in the Pro Football Hall in Canton, Ohio.

Johnson’s interest in photography would occasionally bring him to the student newspaper office, as well as the school’s Sports Information Department, to see if there were any assignments he could shoot. The advantage he had was obvious — no need for an extended tripod.

So now it can be told, hopefully without fear of the retribution of a fastball thrown at our dome: Someone had the inspired idea to recruit Johnson as something of a ringer to play for the Daily Trojan flag football team in the annual “Blood Bowl” game against UCLA’s Daily Bruin.

If we used him as a towering tight end, it would be such an easy target for the quarterback Casey Wian (now reporting news at CNN) and Jon SooHoo (who would become the Dodgers’ longtime official team photographer) to hit over the middle.

If only Johnson could catch an actual pass. That wasn’t obvious until the game started.

Those who try to piece together the facts of what happened that day start with the ridiculousness of a wet, sloppy, muddy mess of the Bruins’ practice field next to Pauley Pavilion. Getting any kind of traction was tough for anyone. Johnson looked like a newborn giraffe.

In a fierce-hitting game (even though it was just flags) recorded as a controversial 12-0 UCLA victory aided and abetted by the Westwood referees, Johnson’s most memorable contribution involved the lone USC touchdown that wasn’t a touchdown. The 80-yard play converted by Paul Vercammen (now at CNN) was called back because of an illegal downfield block. It was called on Johnson, the human broomstick who was probably just looking for someone to grab so he wouldn’t fall over. He couldn’t have blocked anyone if he tried.

But the Legend of Randy Johnson merely started that day. Who could forget all that he meant to the team after that?

So what’s the moral of whatever this story has become?

Pay attention to those kids you hang out with in college who may not always be the gangling, useless knuckleheads you think they’ll turn out to be. Because years later, when you try to reconnect with them, they’re likely to easily forget you ever existed.

The legacy

Randy Johnson had talked to the Angels, Giants, Astros, Phillies, Blue Jays and Cubs prior to the 1985 MLB Draft. Blame Canada for ruining all that. A second-round pick by Montreal, Johnson was in the same ballpark as Will Clark (No. 2), Barry Larkin (No. 4), Barry Bonds (No. 6) and Rafael Palmeiro (No. 22). He was even ahead of Deion Sanders (No. 149 by Kansas City), Bo Jackson (No. 511, by the Angels) and John Smoltz (No. 574 by Detroit).

Johnson and Smoltz would meet up at a key moment years later.

Johnson went on to be traded by the Expos to the Mariners in a five-player deal in May 1989. He went 7-9 with a 4.40 ERA in 22 starts for the Mariners in 1989, but hit his stride in 1990 as he won 14 games and made his first All-Star team.

In the summer of 1992, while pitching for Seattle, Johnson received advice from Nolan Ryan and Texas Rangers pitching coach Tom House, a former USC pitcher himself, on his mechanics that created balance and consistency in his delivery and sent him on a Hall of Fame path. Six months later, on Christmas Day, his father, Bud, died of a heart attack.

“I’d gotten educated from a pitching and mechanical perspective, and then my heart and determination got a lot bigger,” Johnson said. “I vowed to do everything to make it work … I wasn’t trying to be any other pitcher, just the best I could be because I promised that to my dad.”

In March of 1999, Johnson, who just signed a free-agent deal to join the Arizona Diamondbacks, struck out four of the six University of Arizona batters he faced in an exhibition game in Tuscon, Ariz.

“I’m getting back at U of A for all those beatings I used to take at USC,” said Johnson, who last faced the Wildcats in 1985 and walked six, gave up six runs and 13 hits and absorbed a 7-3 loss.

In almost every one of his 22 seasons, Johnson sported a No. 51 XXL jersey. He made his MLB debut wearing No. 57. In 1992, he flipped the numbers and had No. 15 for a short while as a way to try to change his luck. In ’93, he even tried No. 34 (Ryan’s number) with Seattle. With the New York Yankees for 2005 and ’06, he wore No. 41 since the Yankees had issued No. 51 to their All-Star center fielder, Bernie Williams, and it was retired after he was done in ’06.

Johnson’s No. 51 would be retired by the Diamondbacks, whose cap he wears on the Hall plaque. He played in Arizona from 1999 to 2004, and, in the 2001 World Series, he was the D-Backs’ winning pitcher as a starter in Game 2 (a three-hit complete game shutout) and Game 6 (leaving with a 15-2 lead after seven innings) and coming back a day later as the reliever in Game 7 (setting down all four batters he faced in the eighth and ninth inning as his team won in the bottom of the ninth). He shared the Series MVP Award with Curt Schilling. He came back to pitch for Arizona in 2007 and ’08, hoping to record his 300th career win there (he got 15 of them in 40 starts, but No. 300 didn’t happen until he wore No. 51 for San Francisco in 2009).

He’s also in the Seattle Mariners’ Hall of Fame and, while Ichiro Suzuki had No. 51 retired in his honor as a Hall of Fame inductee in 2025, the team said Johnson would be honored as well for wearing No. 51 in 2026.

Johnson, one of 22 USC athletes in baseball, basketball and football who have made the respective sport’s Hall of Fame, had this referenced in G. Scott Thomas’ book, “Cooperstown at the Crossroads”: Johnson’s “quality score of 89 points established him as the top-rated inductee since Mike Schmidt two decades earlier.”

Because the numbers are so numbling dazzling, it’s worth noting that on the back side of Johnson’s lifetime baseball card includes digits that show:

== He recorded more than 250 strikeouts in nine different seasons, an accomplishment unmatched in big-league history. Not even by Nolan Ryan or Walter Johnson.

== His career-best 373 Ks in 249.2 innings during the 2001 season came when he was 37 years old. He had 334 the next year at age 38 in 260 innings. In the top 50 seasons of single-season strike out totals, the only one remotely in that age-old ballpark is Hugh Daily, who, at 36, struck out 483. In 1884. And it took him 500.2 innings.

= 303 wins are 22nd all time, and not likely to be passed up by modern-day pitchers.

= 603 games started is also 21st all time.

= 109 wild pitches — very far down the all-time list at No. 83.

= 190 hit batters, most all-time by a left-hander, tied for sixth all-time, almost 40 more than Nolan Ryan or Don Drysdale. Effectively wild.

But not wild enough when Chris Sale explained when he joined the Atlanta Braves via a trade in 2024, he’d be switching his jersey to number 51 to honor Johnson — even thought he’d never met him, spoke to him, or made much eye contact. Sale won the NL Cy Young Award that year with a league-best and career-high 18 wins (against three losses), a 2.38 ERA and 225 strike outs in 177 innings for a 6.2 WAR. At age 35.

Now, watch the birdie:

Who else wore No. 51 in SoCal sports history? Make a case for:

Randy Cross, UCLA football offensive lineman (1973 to 1975):

Best known: Out of Crespi High in Encino, where he was a state champ in the shot put, Cross almost was swayed to go to USC. “Marv Goux recruited me, as did the University of Texas, Alabama and Nebraska, which was the number one team in the country at the time,” said Cross. “My dad was a big Bruins fan so it was not a hard decision for me to go to UCLA. Terry Donahue was my position coach and he really helped me to understand the game on the college level.” Cross crossed over from right guard to center and protected quarterbacks Mark Harmon and John Sciarra in his senior season. The 6-foot-3 and 265-pound first-team All-American would earn induction into the College Football Hall of Fame in 2011, three years after he included in the UCLA Athletic Hall of Fame. The second-round pick of San Francisco in 1976, after playing for UCLA’s Rose Bowl title-team, Cross stuck with the 49ers his entire 13 year career, making three Pro Bowls and playing on three Super Bowl championships blocking for Joe Montana. For our ears, he became one of the most listenable NFL game analysts when working for CBS and NBC. He, of course, also has a podcast to offer these days.

Not well remembered: Cross played on UCLA’s Bruins’ rugby team to stay in shape during the offseason.

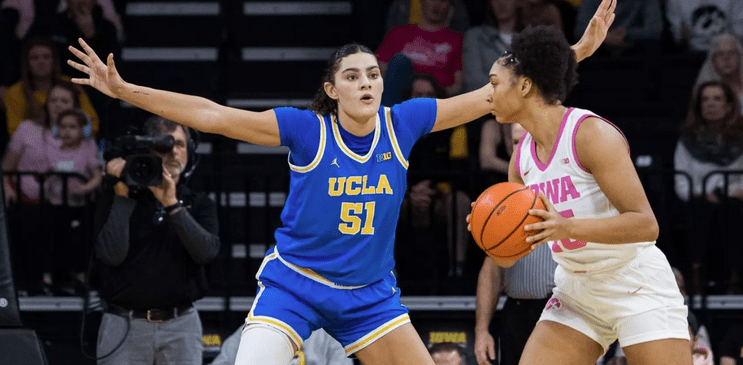

Lauren Betts, UCLA women’s basketball center (2023-24 to present ):

Best known: The 6-foot-7 center started her college career at Stanford as a freshman before transferring to UCLA and helped the Bruins become the No. 1 ranked team for much of the 2024-25 season. Betts was the program’s first national defensive player of the year by setting a single-season blocks record of 100, including a single-game record of nine against Baylor. Betts was the first to reach 600+ points, 300+ rebounds, 100+ blocks in a season. The team’s leading scorer (20.2 points a game had a career-high 33 points at No. 8 Maryland, one of four games in which she scored 30+ points by averaging 19.9 points, 9.8 rebounds, 2.2 assists and 2 blocks.

Chip Banks, USC football linebacker (1978 to 1981):

Best known: A Parade High School All-American from Georgia came across country to start as a freshman for Trojans head coach John Robinson. Banks had 45 tackles and an interception as USC finished 12-1 and won the national title that ’78 season. After his junior year, Robinson called him “one of the greatest players in college football … If he were draftable now and not just as a junior, he’d be taken as one of the top four or five picks.” Banks, voted team captain and part of the pre-season Playboy Magazine All-American team, had 137 total tackles and four interceptions as a senior. For his USC career, Banks piled up 365 tackles (33 for losses), 22 deflected passes, 8 interceptions, 5 fumble recoveries and 1 touchdown.Banks was the No. 3 overall pick by the Cleveland Browns and became the NFL’s Defensive Rookie of the Year in the strike-shortened 1982 season.

Jonathan Broxton, Los Angeles Dodgers pitcher (2005 to 2011):

Best known: A two-time NL All Star in 2009 and ’10, Broxton had 58 saves those two season and a 12-8 record. His seven seasons in L.A. resulted in 84 saves (118 in his 13-year MLB career) and 503 strike outs in 392 innings.

Terry Forster, Los Angeles Dodgers pitcher (1978 to 1982):

Best known: David Letterman made Forster famous for an on-going joke, calling him a “fat tub of goo” even though his MLB official bio listed him at 6-foot-3 and 210 pounds. It was more a reflection of when Forster left the Dodgers and joined the Atlanta Braves, reportedly elevating his delivery platform to 270 pounds. On the last day of the 1982 season, Forster gave up a soul-crusing seventh-inning home run to Joe Morgan, then with San Francisco, costing the Dodgers a playoff spot and he never wore the blue uniform again.

Not well known: Forster’s .397 lifetime batting average (31 hits in 78 at bats) is the greatest for any MLB player in history with either 50 at bats or at least 15 years of major league experience.

We also have:

Larry Sherry, Los Angeles Dodgers pitcher (1958 to 1963)

Anyone else worth nominating?

1 thought on “No. 51: Randy Johnson”