This is the latest post for an ongoing media project — SoCal Sports History 101: The Prime Numbers from 00 to 99 that Uniformly, Uniquely and Unapologetically Reveal The Narrative of Our Region’s Athletic Heritage. Pick a number and highlight an athlete — person, place or thing — most obviously connected to it by fame and fortune, someone who isn’t so obvious, and then take a deeper dive into the most interesting story tied to it. It’s a combination of star power, achievement, longevity, notoriety, and, above all, what makes that athlete so Southern California. Quirkiness and notoriety factor in. And it should open itself to more discussion and debate — which is what sports is best at doing.

The most obvious choices for No. 28:

= Anthony Davis: USC football, Southern California Sun, Los Angeles Rams and Los Angeles Express

= Bert Blyleven: California Angels

= Albie Pearson: Los Angeles/California Angels

= Wes Parker: Los Angeles Dodgers

= Pedro Guerrero: Los Angeles Dodgers

The not-so-obvious choices for No. 28:

= Mike Marshall: Los Angeles Dodgers

= Rui Hachimura: Los Angeles Lakers

The most interesting story for No. 28:

Jack Robinson: UCLA football running back/defensive back (1939 to 1941)

Southern California map pinpoints:

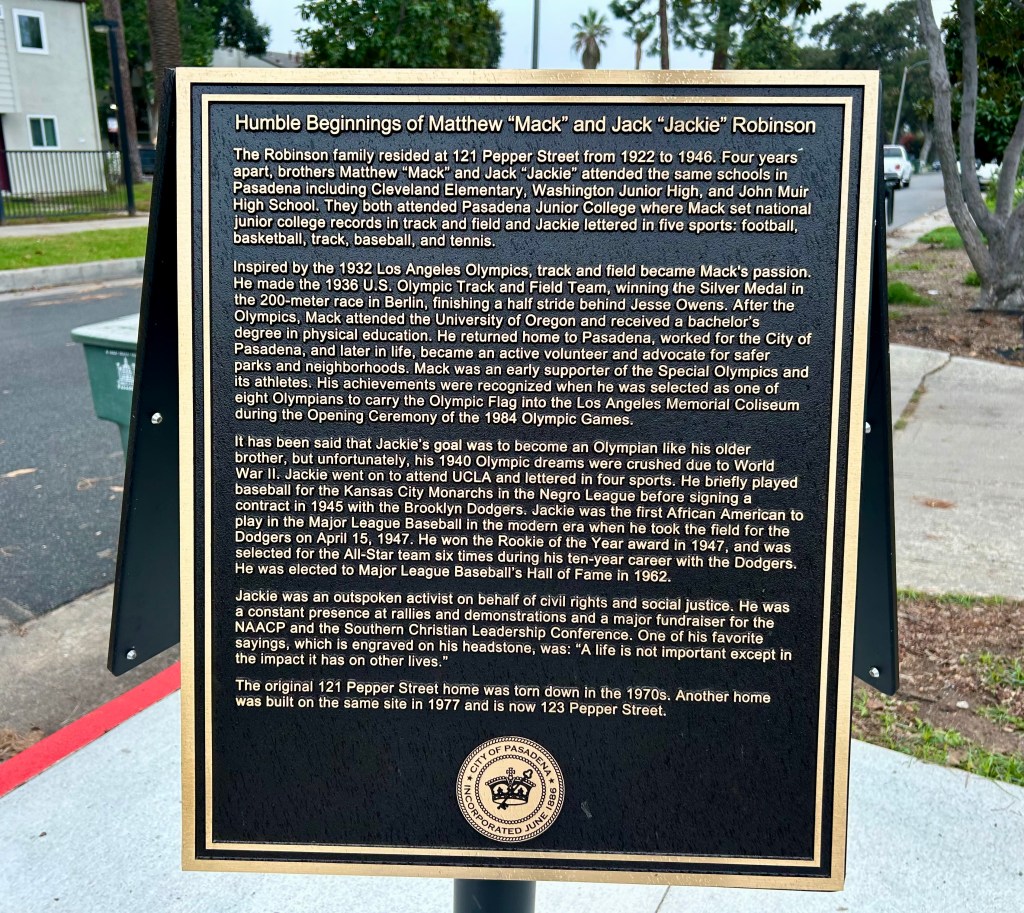

Pasadena, L.A. Coliseum, Westwood

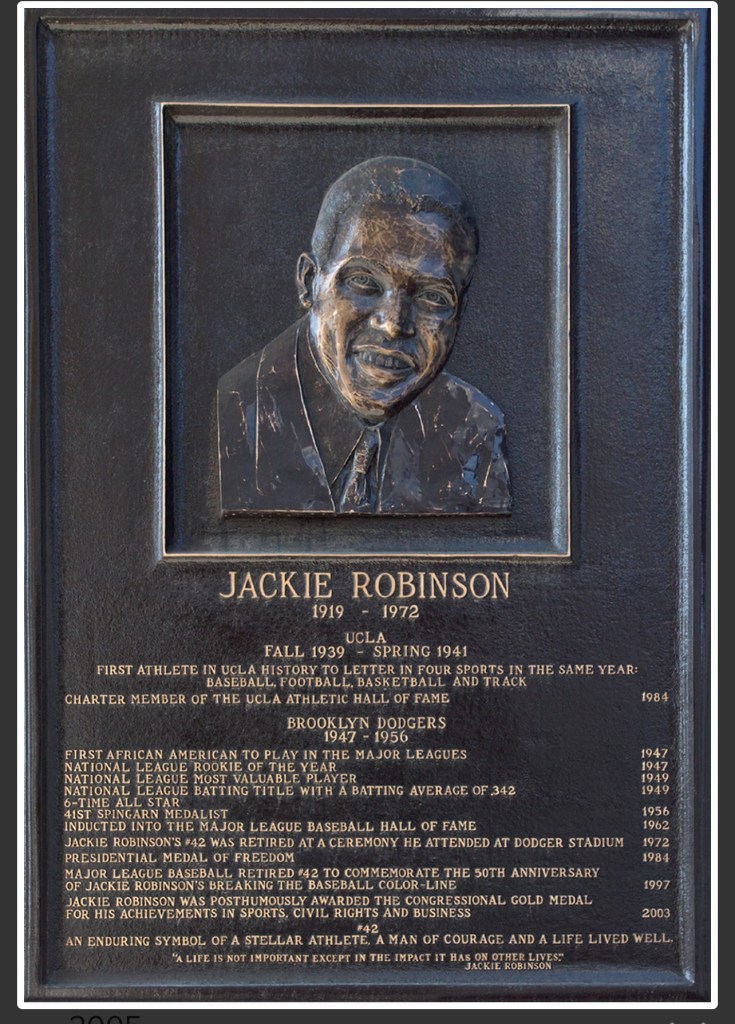

If the only number you associate with Jack Robinson is the No. 42 — the one he was randomly given by the Brooklyn Dodgers when he made his Major League Baseball debut in 1947 — that’s understandable and relatable.

The Pasadena native wore No. 42 for 10 MLB seasons, none of them in Los Angeles as a Dodger, retiring just before their move from Brooklyn. Those 10 seasons played were enough actually to qualify for entrance into the Baseball Hall of Fame based on their most basic voting standards.

Forty-two has been codified in many ways to represent him as well as anyone who believes in social justice reform and restitution on behalf of the African American race.

The thing is, Robinson wouldn’t have been in that position had he not made a name for himself as an athlete — with his given first name of Jack — wearing No. 28 and starring as a football player at UCLA.

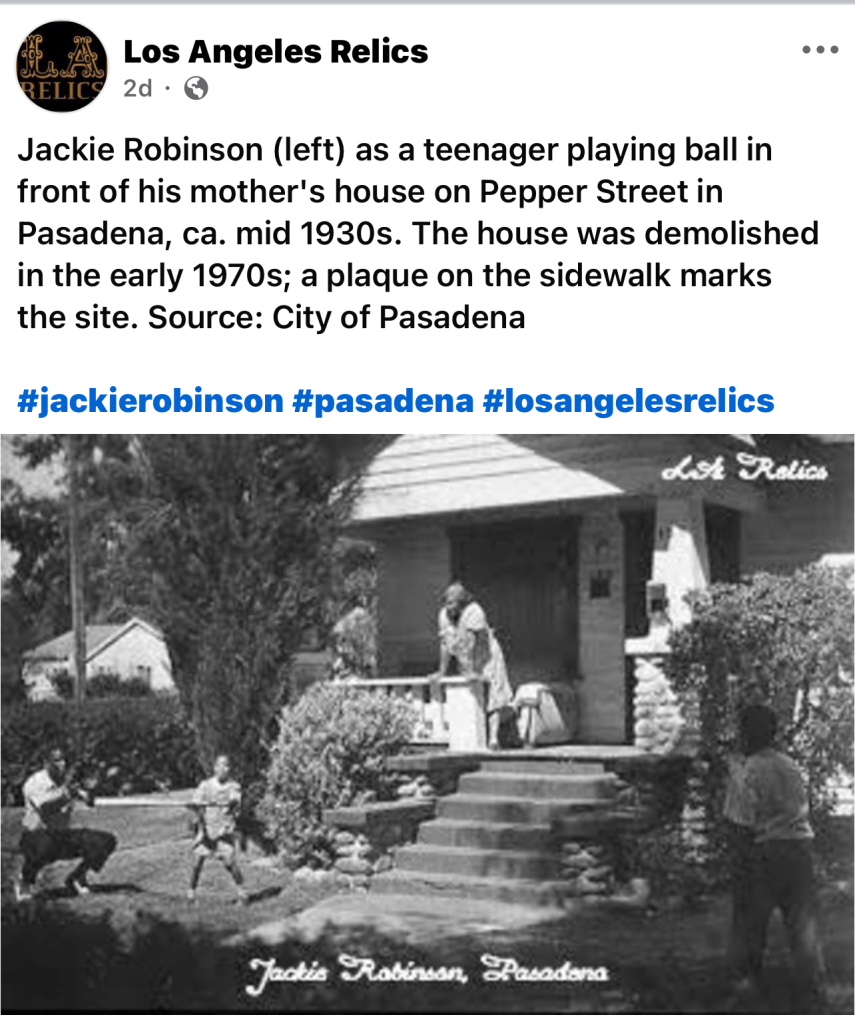

A four-sport athlete at John Muir High in Pasadena, Robinson first made his way to Pasadena City College. His time at UCLA in Westwood was brief, but impactful.

What number did he wear for the UCLA baseball team during his only season of 1940? No one has evidence to show that it was 42. Or any other number. This appears to be the only photo of him in a Bruins baseball jersey, in the team photo, far left.

At Pasadena City College, according to the California Community Colleges website, Robinson batted .417 with 43 runs scored in 24 games in 1938. UCLA records say Robinson posted a .097 batting average in 1940, which included getting four hits and stealing home twice among four bases stolen in one game. He also reportedly stole home 19 times.

He wore No. 18 as a UCLA All-Conference basketball player.

As a football player, he made some extraordinary headlines.

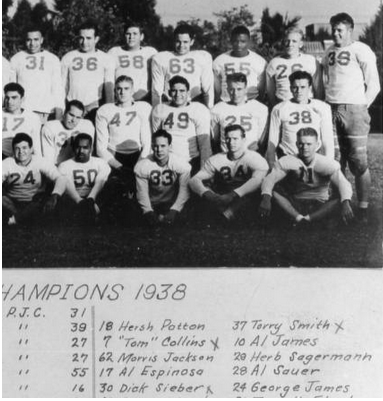

First, at PCC, Robinson wore No. 55 in football — that’s what he’s wearing on a statue outside the Rose Bowl honoring that part of his life. Robinson still owns a school record for the longest run from scrimmage, 99 yards.

But for the two years he played football at UCLA, No. 28 became quite magical.

Here’s a summary of Andy Wittry of NCAA.com pieced it together in 2024 through newspaper clippings:

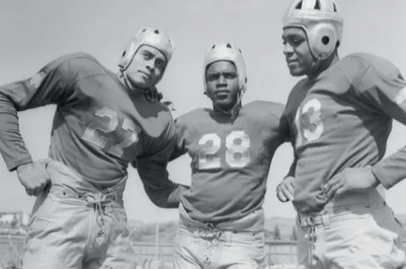

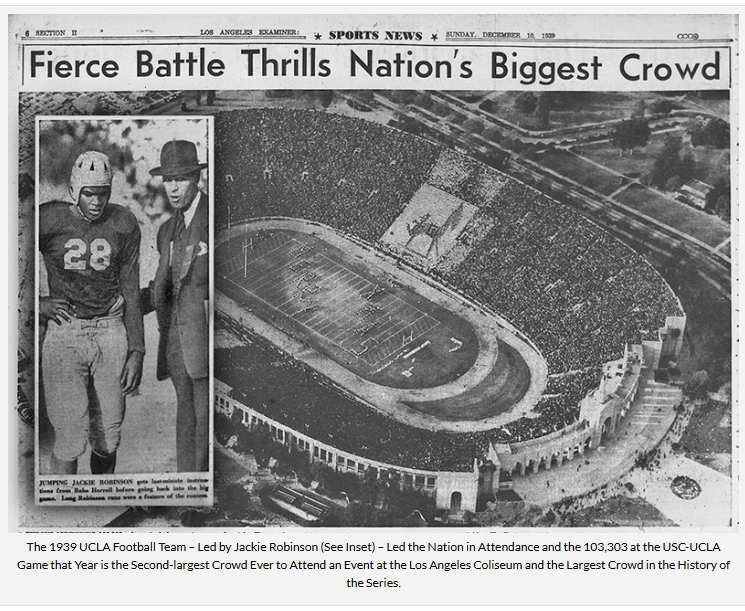

== Entering UCLA as a junior in 1939, Robinson was listed at 6-feet, 180 pounds. The team had a 10-game schedule, with just two road games in Washington and Stanford. Aside from Robinson, three other Black players shined on the roster: Kenny Washington, Woody Strode and Ray Bartlett.

“Before they can say ‘Jack Robinson,’ trouble in copious quantities is apt to break out for opponents of the University of California at Los Angeles on gridirons some of these fine fall days,” the Los Angeles Times’ Paul Zimmerman wrote.

Added Times writer Frank Finch: “UCLA talent scouts plucked the juiciest plum of the 1939 crop of college-bound athletes. Acclaimed as the most brilliant ball carrier ever developed in Southland junior college ranks, Robinson is expected to help make coach Babe Horrell’s Bruins a distinct threat in the 1939 (Pacific Coast) Conference scramble. Robinson was the individual football drawing card on the Coast last year. The (Pasadena Junior College) Bulldogs eleven, with Robinson operating at one of the two halfback berths, consistently drew from 25,000 to 50,000 spectators to the weekly games played at the Rose Bowl. Ninety-nine percent of those present were there because they wanted to see Robinson scoot.”

Consider that USC star runner Grenville Lansdell, the two-time First Team All-Pacific Coast selection and 10th overall pick in the 1940 NFL draft, also went to Pasadena JC. But Robinson had 1,093 rushing yards, 18 touchdowns scored, seven touchdown passes thrown and 131 total points in 11 games during the Single Wing era. His records would stand for more than 60 years. Robinson had touchdown runs in ’38 of 99, 85, 83 and 76 yards, plus an 83-yard punt return.

In the ’39 UCLA opener before some 60,000 at the Coliseum, an odd 6-2 score that led to a victory over Texas Christian and reining Heisman winner Davey O’Brien, it was noted in the United Press recap: “The game brought out a new U.C.L.A. star, Jackie Robinson … who slashed off long gains and lived up generally to his advance ballyhoo as about the fastest thing on cleats on the Pacific Coast.” On UCLA’s game-deciding touchdown, Robinson ran for 45 of the 71 yards, including runs of 29, 12 and 21 yards. He had six carries for 56 yards, second to Kenny Washington’s 11 carries for 65 yards.

Two weeks later at Stanford, UCLA was trailing 14-7 when Robinson intercepted a pass and returned it 49 yards to set up the game-tying touchdown. “Jackie swiped the ball on his own 30 and high tailed it up the pasture with all the zest of a runaway streamliner on a downhill straightaway,” wrote the L.A. Times’ Al Wolf.

Robinson had 62 yards rushing against Stanford and 65 against Washington but UCLA coach Babe Horrell used him as a decoy in a win over Montana — he had just one carry in the Bruins’ victory.

In a 16-6 win over Oregon at the Coliseum, Washington and Robinson connected on a play described as “one of, if not the most spectacular passing play of the entire 1939 NCAA football season … According to the Associated Press report, the ‘Miracle Eye’ camera pictures of the long-distance forward pass thrown (by Washington) was confirmed to have traveled a distance of 52 yards in the air. The streaking Robinson, after receiving the football on the Oregon 23-yard line, left a trio of Ducks defensive players in his wake to score the very first touchdown of his two-year varsity career for the Bruins. Officially, the play went into the books as a 66-yard touchdown toss from Washington to Robinson.” Robinson, who had converted both of his extra point attempts against Washington and Stanford, failed on his third kick of the season but the Bruins still led 9-6 as the first half expired.

Richard Nixon, the vice president of the United States, was giving a speech in 1959 to the Football Writers Association in Chicago and called the Washington-to-Robinson connection as “the best executed play I ever saw … Jackie caught it in the middle of three defenders … I remember as he trotted over the goal line he turned and grinned at his pursuers.”

In the third quarter, Robinson, deployed as the equivalent of a modern-day cornerback in the Bruins’ 6-2-2-1 defensive alignment, intercepted a pass from Oregon’s Bob Smith at the UCLA 17. On the next play, he took a handoff and ran 83 yards around left end on a reverse to score. It was the second-longest run in school history.

UCLA was now nationally ranked No. 19 by the end of October after a 4-0-1 start. The Bruins had never been ranked before this. But Robinson’s knee injury in practice prior to a 20-7 win over Cal forced him to miss that game, as well as a scoreless tie over No. 14 Santa Clara a week later.

Robinson came back in a 13-13 tie over Oregon State with a pair of 31-yard runs. A week after that, he had a game-high 148 yards on 10 carries, out gaining the entire Washington State team (96 yards) in the No. 13 Bruins’ 24-7 win. Robinson scored on a 26-yard touchdown reception from Washington and ran for a 34-yard touchdown moments later. His last play before being taken out of the game was a 32-yard run that set up another touchdown.

Then came the rivalry game against No. 3 USC, as UCLA was up to No. 9. Neither team had lost. A trip to the Rose Bowl was on the line.

Who would have guessed it would end in a scoreless tie.

Robinson was involved in one the biggest plays of the game, when he and teammate Ned Mathews tackled USC’s Grenny Lansdell just shy of the goal line in the first quarter, forcing a fumble. The ball appeared to come loose on Robinson’s low tackle. UCLA recovered.

When the dust settled, USC was 8-0-2 overall, 5-0-2 in conference. UCLA was 6-0-4, 5-0-1 in conference. The Pacific Coast Conference held a vote. Why couldn’t the Bruins play the Trojans in a Rose Bowl rematch?

“Why give that $100,000 to some Eastern team?” Robinson asked, according to the L.A. Times. Tennessee, ranked No. 2 in the AP poll, was ultimately selected as USC’s opponent. UCLA finished ranked No. 7.

Robinson had set the UCLA record for yards per carry in a season at 12.2 yards per attempt on 42 carries in 1939.

As a senior, Robinson was All-Western Conference and led the Bruins in rushing (383 yards), passing (444 yards), total offense (827 yards), scoring (36 points) and punt-return average (21 yards). In that last category, he led the NCAA two seasons in a row. But UCLA, without Washington, finished 1-9 overall, its only win against Washington State at the Coliseum, 34-26, in mid-November, before finishing with a 28-12 loss to USC in a rematch before 70,000 later that month.

The rest is history? Seems that’s how it shook out.

After Washington left UCLA and spent 1940 playing semi-pro football with the Hollywood Bears in the Pacific Coast Football League, Robinson joined the league with him in 1941, but went to the rival Los Angeles Bulldogs. He wore No. 17.

Much like in pre-expansion baseball at the time, the league was professional-quality. Unlike their baseball counterparts, it had integrated teams.

In his debut there, according to the black weekly newspaper the Los Angeles Sentinel, Robinson ran 41 yards for a touchdown. The ex-UCLA teammates faced each other in the December 21 season finale with Washington’s Bears beating Robinson’s Bulldogs, 17-10. Robinson gave the Bulldogs a 10-3 lead throwing a touchdown pass, but an injury in the second quarter knocked him out of the game.

Earlier that season, Robinson played for an integrated team in Honolulu — whose season ended on Dec. 3, four days before the attack on Pearl Harbor. Robinson was on his way back to California by then. He came back in December of ’41 trying to find a spot as a running back with the Bulldogs, but war had broken out.

Robinson was drafted into the Army soon after, and wasn’t able to play any sport again until his discharge in 1944. But again, he picked football and the Pacific Coast League. A severe ankle injury that season ended his football career — and, since he still needed work, that’s when he turned to baseball and the Negro Leagues, his springboard to signing with the Dodgers.

Washington and Strode eventually broke the NFL’s self-imposed color line in 1946 with the Los Angeles Rams. Robinson had just finished playing with the Kansas City Monarchs of the Negro Leagues at age 26 in ’45, and then signed with the Dodgers, stashed away at their Montreal Triple A affiliate for a season.

Then came 1947. After his MLB days were over, Robinson was recruited to be the general manager of the 1966 Brooklyn Dodgers of the Continental Football League — a role mostly ceremonial, but still a tribute to his football knowledge.

The plaque that is in the Los Angeles Coliseum’s Court of Honor adds a lot of that history as well:

Who else wore No. 28 in SoCal sports history?

Make a case for:

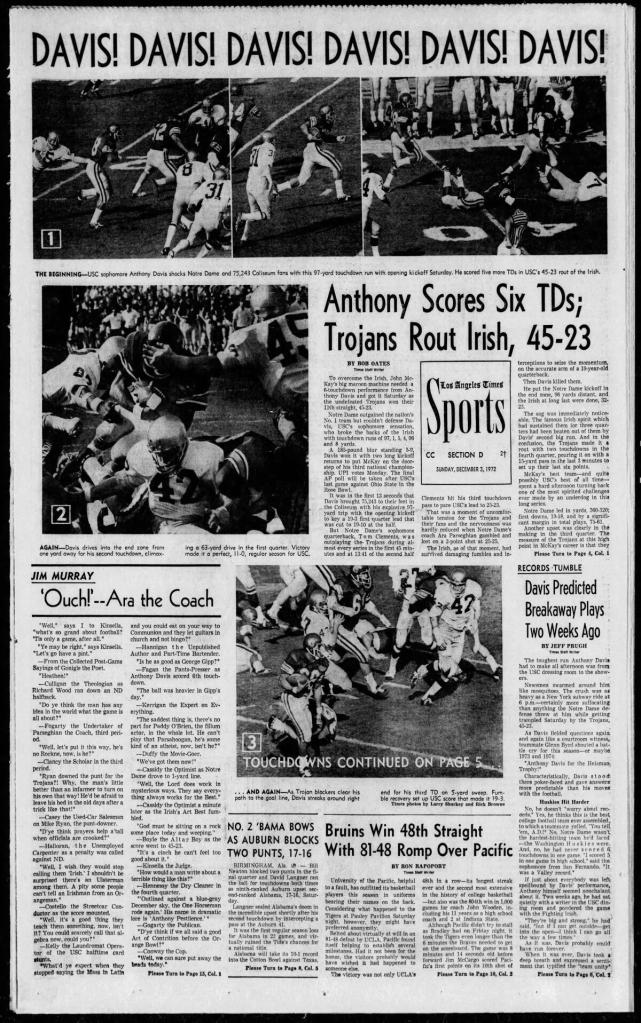

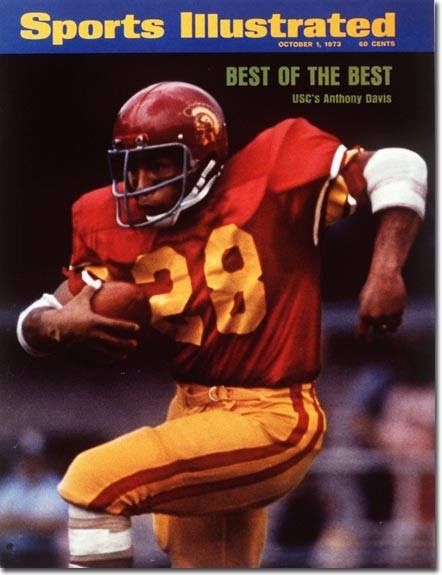

Anthony Davis, USC football tailback (1972 to 1974); WFL Southern California Sun tailback (1974), NFL Los Angeles Rams tailback (1978), USFL Los Angeles Express tailback (1983):

Best known: “The Notre Dame Killer” is the way one of the Trojans’ greatest football players will sign an autograph when asked. His signature reminds everyone, including himself, how he scored 11 of his 42 regular-season TDs in just three games against the Irish. It started with six in a 45-23 win in 1972 as a sophomore (a 97-yard kickoff return to help the game, and a 96-yard kickoff return later, plus runs of 1, 5, 4 and 8 yards). Four more came in his legionary 1974 performance against the Irish as a senior at the Coliseum, sparking USC’s comeback from a 24-0 second-quarter deficit with a 102-yard kickoff return to start the second half, scoring four TDs in a 55-24 win, accounting for 26 of USC’s first 27 points against the No. 4-ranked team. But the game came after the Heisman ballots were already cast, so it somewhat explains how he finished runner up to Ohio State junior Archie Griffin – and why that situation won’t happen again as the ballots are now due later into the season.

In his three-year college term, the 5-foot-9, 185-pound former San Fernando High of Pacoima star (who then wore No. 15) who once had a five-TD game in 1972. His Trojan career includes the fact he was the first sophomore to surpass 1,000 yards en route to compiling 3,426 yards rushing in 33 regular-season games and setting an NCAA record with six career touchdowns on kickoff returns. USC was 31-3-2 in the games he played, spanning three conference titles, three Rose Bowl wins and two national titles. That got him inducted into the College Football Hall of Fame in 2005. His USC Athletic Hall of Fame induction in 1999 was followed up by being part of the 2021 class of the Rose Bowl Hall of Fame.

Not well remembered: Davis wore No. 28 not just at USC, but for at least a half dozen other professional teams. After the New York Jets took him 37th overall – in the second round – during the 1975 NFL Draft, Davis opted for the new World Football League and a five-year $1.7 million deal with a $200,000 cash bonus and a Rolls-Royce to wear No. 28 for the Anaheim Stadium-based Southern California Sun, in its second season. The fact Davis led the WFL in rushing with 1,200 yards, 239 carries and 16 touchdowns — and completed 4 of 11 passes for a touchdown — is easily lost as the league folded before there could be a 1976 season.

The Canadian Football League scooped him up for the 1976 season with the Toronto Argonauts. It wasn’t memorable. The NFL called back in 1976 – former USC coach John McKay wanted him for his 0-14 Tampa Bay Bucs, but Davis sputtered in ’77. After a stop in Houston, Davis came back to the Los Angeles Rams and former USC coach John Robinson in 1978 – four games, three rushes, seven yards. Wearing No. 28. After a layoff of about five years, Davis came back at age 30 to help the upstart United States Football League’s L.A. Express. Just 12 rushes for 32 yards. Wearing No. 28. In post-football times, Davis, an outfielder on USC’s 1973 and ’74 College World Series champion baseball teams, joined the Independent Winter League Senior Professional Baseball Association in 1990 as an outfielder for the San Bernardino Pride. The league disbanded half way through its season. He was their version of Bo Jackson, playing with players such as Derrel Thomas and Vida Blue. Still not sure, but we’d give it a fair guess that Davis wore No. 28 there as well.

Wes Parker, Los Angeles Dodgers first baseman (1964 to 1972):

Best known: The March 21, 1971 cover of Sports Illustrated made Parker appear as the All-American “sudden star.” A West L.A. native who played at Harvard Military Academy (now Harvard-Westlake) and moved onto Claremont Men’s College and USC was a six-time Gold Glove winner who finished fifth in the 1970 MVP voting when he led the league with 47 doubles, hit .319, drove in 111 runs, played in all 161 games and was four hits short of 200. In 2007, Parker was named to the Rawlings’ All-Time Gold Glove Team. For many years, he was known as “the last Dodger to hit for the cycle,” which he also did in ’70, a feat not repeated in the franchise until nearly 40 years later.

Not well remembered: Parker retired at age 32 after nine MLB seasons. The Dodgers were trying to bring Bill Buckner (and eventually Steve Garvey) in to replace him. Parker went to Japan in ’74, where he also won a Diamond Glove (now called a Gold Glove) for the Nankai Hawks. His extensive SABR.com biography explains more of why he left the MLB in ’72 to try broadcasting: “My main reason for concluding my career is to allow myself time to enjoy the many interests which I have in life while I’m still young. The desire to lead a more settled life is another contributing factor.”

Pedro Guerrero, Los Angeles Dodgers outfielder/third baseman/first baseman (1980 to 1988):

Best known: A four-time NL All Star (’81, ’83, ’85 and ’87) and co-MVP of the ’81 World Series, Guerrero had 11 years with the Dodgers where he hit .309 with 171 homers and 585 RBIs in 1,036 games. He led the NL with a .577 slugging percentage and .422 OPS in ’85, where he had a career-best 33 homers. He has a lifetime average at exactly .300. He hit .320 in 1985 and was out for the start of the ’86 season when he severely injured his knee sliding during spring training. He came back in 1987 to hit .338.

Not well remembered: Guerrero wore No. 57 in his first two call ups in ’79 and ’79 at ages 22 and 23. His biography at SABR.com includes his post-playing career near-death experiences.

Mike Marshall, Los Angeles Dodgers relief pitcher (1974 to 1976):

Best known: The first NL reliever to win a Cy Young, Marshall set an MLB record with 106 appearances, 83 games finished, logging more than 200 innings, posting a 15-12 record with 21 saves to go with a 2.42 ERA. “Iron Mike” started a streak on June 18 that season where he worked 13 consecutive games in 16 days and set a record of nine-straight appearances, picking up five victories in six days. Counting the All-Star Game, league playoffs, and World Series, Marshall appeared in 114 games and threw 222 1/3 innings in 192 days. His biography at SABR.com includes this statement: His season is unique in baseball’s long history. Nobody else has come close to 106 games, not even in the 19th century, when pitchers were just 50 feet from home plate and throwing underhand. What was he thinking? He was thinking he knew better. And he backed up his opinions with science. Two weeks into the 1975 season, Marshall went on the disabled list with torn rib cartilage and couldn’t regain his form — at a time he also fought with management over their management of him. After being traded to the Atlanta Braves in June of 1976, Marshall was summed up by Los Angeles Times columnist Jim Murray: “(There) isn’t a team in baseball that wouldn’t have wanted Mike if it could keep the right arm and throw the rest away.”

Not well remembered: Ever the idiosyncratic contrarian, Marshall had his PhD in Kinesiology to back the science that pitching frequently — even while throwing a screwball — was more healthy than not. He was also the teammate who helped convince Tommy John that same season to get the elbow surgery that now bears his name, which was also something Marshall avoided his entire career. Marshall also designed a rehab program for John afterward.

Bert Blyleven, California Angels pitcher (1989 to 1992):

Best known: The last three seasons of his 22-year eventual Hall of Fame career was spent with the Angels, where he led the AL with 17 losses and had the highest ERA of 5.78 in 1988. But the next season, he threw five shutouts to go with a 17-5 record.

Not well remembered: In his extensive SABR.com biog, Blyleven says about playing in Anaheim: “I’ve dreamt about this since I was growing up” and graduating from Santiago High in Garden Grove. The youngest of Blyleven’s seven brothers, Joe, also from Santiago High, once threw a shutout for the Angels’ Single-A franchise in 1978.

Pat Studstill, Los Angeles Rams split end, wide receiver, halfback, punter (1968 to 1971):

Best known: Studstill’s studliness was the fact he was one of the last NFL players to go without a facemask. A two-time Pro Bowl receiver with Detroit, leading the league with 1,266 receiving yards and an average of 90.4 yards a game in ’66, Studstill came to the Rams and led the league in punts with 81 in ’68 and 80 more in ’69, along with a league-best 3,259 yards punting.

Jim Wolf, Major League Baseball umpire (2004 to present):

Best known: The older brother by six years of MLB pitcher Randy Wolff (a 16-year career from 1999 to 2015, out of El Camino Real High in Woodland Hills and Pepperdine University, including two seasons with the Dodgers), Jim Wolf was also born in West Hills, played catcher at El Camino Real and Pierce College, and made his MLB debut in ’99 as well, just a couple months after Randy. Jim was the third-base umpire in San Francisco as the Giants faced the Philadelphia Phillies — where Randy was in the visiting dugout. The rules never allowed Jim to umpire a game when Randy was involved. Jim worked through the Arizona Rookie League, the South Atlantic League, the California League, the Texas League and the Pacific Coast League before he was a full-time MLB umpire in 2004. He has worked two World Series (2015 and ’19) and one All-Star Game in Anaheim in 2010. He was not only behind the plate for Dallas Braden’s perfect game on Mother’s Day, May 9, 2010.

Not well known: Jim Wolf made the call on Clayton Kershaw’s 3,000th strike out on July 2, 2025 at Dodger Stadium — a called strike three to end the top of the sixth inning in dramatic fashion as Kershaw was making his 100th and final pitch of the contest. Some 17 years earlier, Wolf was the first base umpire when Kershaw made his big league debut on May 25, 2008 at Dodger Stadium and recorded his first strikeout. Two months later, on July 27, Jim Wolf was the home plate umpire for the game that turned out to be Kershaw’s first win. For the 2009 season, 21-year-old Kershaw (4.7 WAR, 8-8, 2.79 ERA in 30 starts) was a Dodger teammate of 32-year-old Randy Wolf (3.9 WAR, 11-7, 3.23 ERA and tied for the NL lead with 34 starts) as the two left-handed starters on a team that lost to Philadelphia in the NLCS under manager Joe Torre.

Rui Hachimura, Los Angeles Lakers forward (2022-23 to present): The 6-foot-8, 230-pounder was born in Toyama, Japan and went to high school in Sendai, Japan before coming to the U.S. to play at Gonzaga for three seasons (his last as the West Coast Conference Player of the Year). The ninth overall pick by Washington in the 2019 NBA draft — the first Japanese player ever picked in the first round of an NBA draft — he came to the Lakers in a trade mid-season ’23 and signed a multi-year deal to stay that summer. He put up career highs of 36 and 32 points in the ’24 season.

Hector Olivera, Los Angeles Dodgers infielder (2015): Although he never played a game in L.A., and only wore No. 28 for the Atlanta Braves for parts of two seasons, the Dodgers had them in their farm system at the Rookie League level (six games), Double-A (six games) and then Triple-A (seven games) before he was sent to the Braves in a three-team deal that included Mat Latos, Bronson Arroyo and Alex Wood. The Cuban national standout played from age 18 to 28 in his native country, hitting as high as .353 in 2007 and .341 in 2012. When he defected, the Dodgers had a six-year, $62.5 million deal for him that included a $28 million signing bonus. He had just a -0.3 WAR during his MLB career (30 games) and was suspended 82 games the next season under the league’s domestic violence policy. He retired at 32 after a brief stint with the independent Sugar Land Skeeters.

Haixia Zheng, Los Angeles Sparks center (1997 to 1998): How do you overlook at 6-foot-8 player from China just trying to make some cash in the WNBA?

Have you heard this story:

Albie Pearson: Los Angeles/California Angels outfielder (1961 to 1966):

Editor’s Note: Dan Durbin, founder and director of the USC Annenberg Institute of Sports, Media and Society and creator of the African-American Experience in Major League Baseball research program, contributed this entry:

If you ever spent any time on the phone with Albie Pearson, you almost certainly had the rare privilege of having a former Major League Baseball player pray the blood of Jesus over you.

Albie was one of the few stars on the early Los Angeles Angels, a 1961 American League expansion team that would eventually work its way down the 5 Freeway to Anaheim.

A diminutive 5-foot-5 and 140 pounds, Pearson stood tall on an Angels team that had little else to offer baseball.

Movie and television cowboy Gene Autry, the man who set the record for the most stars on the Hollywood Walk of Fame and a rabid baseball fan, had been awarded the new west coast American League franchise in 1960. The original Los Angeles Angels was a Pacific Coast League team that was loaded with local stars, particularly, at the end, a beer-drinking power hitter named Steve Bilko.

Trying to create some continuity with the PCL Angels, Autry hired Bilko who could clobber a fastball but never quite mastered hitting curves, sliders, change-ups or any other pitch that didn’t rush down the center of the plate. Other early “stars” of the newborn Angels included hard-drinking Hollywood playboy Bo Belinsky, solid starter Dean Chance and Ryne Duren whose pitching frightened even the stoutest ballplayers as he threw one of the hardest and most wildly erratic fastballs the game had ever seen. No one, Duren least of all, knew where the hell his pitch would end up.

Albie was a fresh breath of normalcy in this weirdly concocted expansion brew.

A respectable contact hitter with some speed on the base-path, he became a quiet star, the only real offensive star on a team that would remain huddled in the shadow of the big-budget Brooklyn transplant Dodgers.

While the Dodgers racked up World Series championships on the arms of superstars Sandy Koufax and Don Drysdale, the Angels would suffer in obscurity, always the weaker, less talented largely unnoticed younger brother. They sat in their corner quietly.

With no home run power and his slight frame, Pearson was the embodiment of a team that could only stand and wait for better days.

Though, Albie had his moments.

In what may have been her last public appearance, Marilyn Monroe was accompanied by Pearson as she took part in pregame ceremonies before an Angels charity game on June 1, 1962.

Playing in the heart of Tinseltown, Albie appeared in several Hollywood movies, only occasionally being left on the cutting room floor.

But Albie had more on his mind than baseball.

As his career wound down, Pearson became an ordained minister. He ministered at several different churches. But his greatest mission was Father’s Heart Ranch, a home in Desert Hot Springs for abused and abandoned boys.

If in roughly 2007 you wanted to create a program on, say, the expansion Angels at a school like the University of Southern California, you would likely have been given Albie’s number at the Ranch.

You would call him up and immediately hear his cheerful voice answering your call. Over the next hour or so, he would talk about baseball, his life, his ministry and, inevitably, he would invite you to take part in a heartfelt prayer for you and your work. You would, of course, accept the invitation. It was Albie Pearson, after all.

And the man was so sincere and kind. He wouldn’t show up at your program. But Albie Pearson would pray the blood of Jesus over you.

When Albie played for the Angels, the team’s caps had halos stitched in their crowns. By the time Albie died on February 21, 2023, he had doubtless earned that halo.

Post script

== Born in Alhambra and an El Monte native, Pearson played more than 300 big-league games with Washington (wearing No. 6, the 1958 AL Rookie of the Year) and Baltimore (wearing No.21) before the Angels took him in the expansion draft with the 30th — and final – selection.

== He became the first Los Angeles Angels to score a run – in the April 11, 1961 opener at Baltimore, batting third and playing right field.Pearson drew a two-out walk against Milt Pappas and scored ahead of Ted Kluszewski’s home run in the old Memorial Stadium, helping Eli Grba to the complete-game 7-2 win.

== In the 1963 All Star Game, Pearson was the American League’s starting center fielder, batting second at Cleveland Stadium, perhaps since Mickey Mantle was injured. Pearson went 2-for-4 with a run scored.

== In 2012, Pearson told the San Bernardino Sun about that day he had with Marilyn Monroe:

She was standing over in the far corner of the dugout, completely in the shadows. And she’s pale and shaking and I’m thinking this can’t be Marilyn Monroe, the famous movie star. Anyway, we’re called out to home plate and I thought I would have to drag her out of that corner. But once she hit that top step of the dugout she became Marilyn Monroe the movie star, smiling and waving. I was simply amazed at the transformation.

Well, we finish the presentation and I walk her back. Now, this whole time I never said a word to her and she never spoke to me. Once we’re back in the dugout, she turns back into this shy, withdrawn person. And the strangest thing, all this time I have these Bible verses running through my mind. Marilyn Monroe and Bible verses. Talk about God working in mysterious ways.

As she’s leaving, she suddenly turns to me. And she says, `What is it you are trying to tell me?’ And I was just absolutely speechless. She looked so lost and lonely and I felt I needed to say something, but what do you say to Marilyn Monroe?

She died August 5, about a month later.

== Pearson recorded several albums, including a faith-based LP called “What A Wonderful Life,” the name of one of the 12 songs on it, along with songs such as “The Lord is My Shepherd,” “A Sportsman’s Prayer” and “A Better Life.”

== A Sports Illustrated piece on him in 1962 is titled “The Littlest Angel: The Center Fielder for Los Angeles is a Hot Dog At the Plate and Behaves Publicly Like Every Small Man since Napoleon, So Why Does He Refuse to Shoot Pool with Bo Belinsky?” In that, Pearson cites a file he had with the Equitable Life Assurance Society that measures him at 5-feet, 5 3/8 inches – still almost two feet taller than Eddie Gaedel.

We also have:

Clarence Davis, USC football tailback (1969 to 1970)

J.D. Martinez, Los Angeles Dodgers DH (2023)

Todd Hollandsworth, Los Angeles Dodgers outfielder (1995 to 2000)

Jose Molina, Anaheim Angels/Los Angeles Angels of Anaheim catcher (2001 to 2007)

Vada Pinson, California Angels outfielder (1972 to 1973)

Monte Jackson, Los Angeles Rams defensive back (1975 to 1977)

Pat Studstill, Los Angeles Rams punter/wide receiver (1968 to 1971)

Steve Duchesne, Los Angeles Kings defenseman (1986-87 to 1990-91, 1998-99)

Jarret Stoll, Los Angeles Kings forward (2008-09 to 2014-15)

D.J. Mbenga, Los Angeles Lakers center (2007-08 to 2009-10)

Jason Kapono, Los Angeles Lakers forward (2011-12)

For the record:

== The Rams retired No. 28 for Pro Football Hall of Fame running back Marshall Faulk, who wore that during his entire stay in St. Louis for the franchise from 1999 to 2005 (after starting in Indianapolis).

Anyone else worth nominating?

3 thoughts on “No. 28: Jack Robinson”