This is the latest post for an ongoing media project — SoCal Sports History 101: The Prime Numbers from 00 to 99 that Uniformly, Uniquely and Unapologetically Reveal The Narrative of Our Region’s Athletic Heritage. Pick a number and highlight an athlete — person, place or thing — most obviously connected to it by fame and fortune, someone who isn’t so obvious, and then take a deeper dive into the most interesting story tied to it. It’s a combination of star power, achievement, longevity, notoriety, and, above all, what makes that athlete so Southern California. Quirkiness and notoriety factor in. And it should open itself to more discussion and debate — which is what sports is best at doing.

The most obvious choices for No. 6:

= Steve Garvey: Los Angeles Dodgers

= Mark Sanchez: USC football, Mission Viejo High football

= Eddie Jones: Los Angeles Lakers

= Bronny James: USC basketball

= Carl Furrillo: Los Angeles Dodgers

= Sue Enquist: UCLA softball

= Joe Torre: Los Angeles Dodgers manager

The not-so-obvious choices for No. 6:

= Marc Wilson: Los Angeles Raiders

= Anthony Rendon: Los Angeles Angels

= Ron Fairly: Los Angeles Dodgers/California Angels via USC

= Adam Morrison: Los Angeles Lakers

The most interesting story for No. 6:

Steve Garvey: Los Angeles Dodgers third baseman/first baseman (1969 to 1982)

Southern California map pinpoints:

Los Angeles (Dodger Stadium); Palm Springs

Steve Garvey’ offered a modest proposal in the fall of 2023. It had nothing to do with him pitching another reverse mortgage plan, some hair restoration, weight-loss supplements or switching to a brand of particular dog food.

At the website for his U.S. Seanate run campaign, a popup asked California voters if they were willing to “give $6 for #6.” It would happen all very painlessly through something called efund.

Ah, the joy of six.

“Our campaign is focused on quality-of-life issues, public safety, and education. As a U.S. Senator, I will serve with commonsense, compassion, and will work to build consensus to benefit all of the people of California,” the script said quoting one of the Los Angeles Dodgers’ most popular and productive players in the 1970s and ’80s.

The CEO of Team Garvey said he needed a lot support as a Republican in a very Democratic state for the March 5, 2024 primaries.

None of this really came out of the blue.

During his baseball career, he had been planting seeds about his next career in some type of high-profile public office. For those who made a connection to the red No. 6 on the front of his Dodgers’ jersey — which he also carried onto a few more seasons in San Diego — the nostalgia was thick and the opportunity ripe as a controversial Republican president was somehow circling back to the pulpit and gaining momentum on a campaign of anti-blue sentiment.

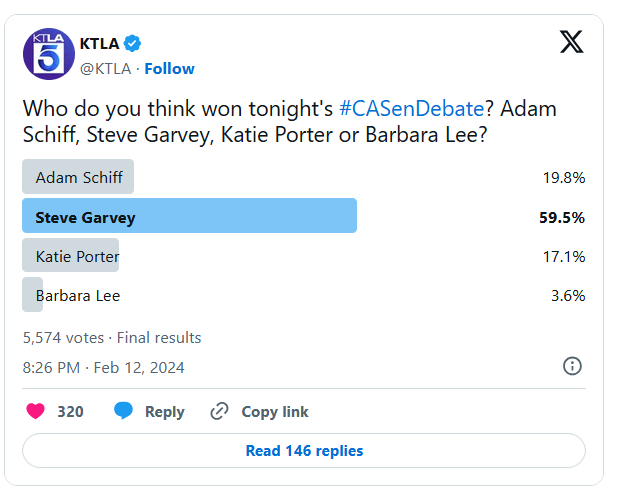

The twist in all this — the California primaries reward the top two vote-getters regardless of party moved onto the Nov. 5 general election. In this wrestling match to finally get the seat once held by Diane Feinstein, Democratic candidate Adam Schiff was an early favorite but he created a campaign strategy targeting Garvey as his main competitor — inciting more Republican support for Garvey — because Democrat Katie Porter provided a far-more serious threat to Schiff.

As a result, Schiff manipulated it so he and Garvey finished 1-2 in the primaries with nearly the same number of votes.

Now there were eight months left of campaigning for a spot that really wasn’t that close.

Back in February of 2024, a Los Angeles Times story tried to layout the contradictory “family values” life Garvey has led coming to this point — including a disassociation with one of his daughters and his grandson. He has seven children. Not all keep in touch.

That can’t help with garnering votes.

By June of ’24, Michael Weinreb, a San Francisco Bay-Area screen writer, put up on his Substack account called “Throwbacks: A Newsletter about Sports History and Culture:”

“Dozens of ex-athletes have attempted to transition into politics, some of them driven by noble aims. But what sets Garvey’s Senate run apart from all the others is that I’m not sure what it is about at all. In fact, it seems entirely devoid of a purpose beyond the name of the candidate himself.

“It’s not just that Garvey is running as a Republican in a deep-blue state in perhaps the most polarized era in modern American history; it’s that he doesn’t even seem to be trying. He speaks in aphorisms that mean absolutely nothing; he won’t even express a definitive opinion about the standard-bearer of his own party. It’s as if he’s running just to say he ran, because this is what he always appeared destined to do when he was younger. It’s as if he’s trying to fill out the gaps in his own story.

“There’s something kind of sad about this. But it also feels like a telling metaphor for modern American politics at a moment when celebrity has outweighed substance. Best as I can tell, Steve Garvey is running for office because of his own hollow conception of fame. …

“For a while, it appeared Garvey stood above it all, and then his own hypocrisy rendered him a punchline. Maybe it’s cynicism; maybe it’s naivete. But either way, it’s as if he’s trying one last time to will into truth his own hollow fiction.”

At the website Sons of Steve Garvey, billed as “random rantings and ravings about the Los Angeles Dodgers, written by a small consortium of rabid Dodger fans,” there was never a Garvey endorsement of his political aspiration.

We had a flashback to 1998 when we caught up with Garvey at a North Hollywood baseball card shop named Porky’s. At the time, Jessie “The Body” Ventura had just won the governorship Minnesota. Garvey told us that Barbara Boxer, who had just been re-elected California state senior, “could have been had” if another Republican — like him? — had stepped up to get that spot.

Even then, he said he had his eye on Feinstein, whose six-year term was coming up in 2000. But he knew he wasn’t getting any younger.

“You know, I’m going to be 50- in December,” he told me than (and he just had a two-week old daughter born).

So now, in 2024, the 75-year-old Garv thought he could change the narrative of a “man of the people” journey.

Mailers to constituents tried to make his case through a mock up of a baseball card. Another mailer tried to make sure that even if he has supported Donald Trump in previous presidential elections, he would like to be thought of more as someone aligned with former president Ronald Reagan — sending out a 1984 photo of the two once together in San Diego.

Garvey tried to use a new-age baseball stat — Wins Above Replacement — as a way to show how Schiff’s shortcomings could be best measured.

“He just doesn’t need to be replaced. He needs to be defeated,” Garvey wrote.

Even though a story in The Nation projected that Garvey could not be underestimated, it all played out as suspected. Photo ops on Skid Row in L.A. and a trip to Israel in the middle of a war to try to see for himself what was going on weren’t effective.

The fact remains that, by early November, Schiff easily send Garvey to the showers with a 59-41 percent victory that was called by an Associated Press projection about one minute after the California voting precincts closed.

Garvey (who goes with the social media handle of @SteveGarvey6) used even more twisted numerical logic in his November election-night remarks in Rancho Mirage, which occurred just days after the Dodgers’ 2024 World Series triumph, to make it appear he achieved something (by fact that California is the most populated state and likewise produces the most voters):

In baseball, like in many professional sports, there’s a tradition of members of the opposing team to congratulate the winners. Often times with a handshake on the field or even a visit to the opponent’s clubhouse. In that same spirit I congratulate Congressman Adam Schiff on his victory. Using their enormous power the voters have elected him the next U.S. Senator from California. And I respect that and wish him good choices for all of the people in the years to come. I want you to know that despite the outcome that when the counting is over we will have gotten the fourth-most number of votes in the country. This means that everyone in California does have a voice. And it will only grow louder and louder. ….

I fell in love with California since my first day when I arrived on September 1,1969, when I was a rookie with the Los Angeles Dodgers. And want it to once again be the heartbeat of America. And I want the American Dream to live on and thrive. Because as the great Ronald Reagan once said — “As long as that dream lives, as long as we continue to defend it, America has a future, and all mankind has reason to hope.” Thank you again. God bless you and God Bless America.

Citizen Garvey’s politicking was done.

Why, again, had it even started?

For someone who had been cultivating name, image and likeness every one of the 14 season he spent with the Dodgers, and five more in San Diego with the Padres before retiring in 1987, Garvey likely didn’t think any amount of self-inflected wounds could sway those voting on Baseball’s Hall of Fame as well as any pursuit of public office.

The concept of Garvey on Capitol Hill doing some legislating seemed a bit surreal. Almost too perfect, even for someone who basked in perfection and branded himself as the All-American boy. Teammates could admire what he was doing and be a bit jealous about the attention garnered in the same glove-swipe that dug a throw out of the dirt.

In the 1970s, Garvey was the red, white and blue Dodger coverboy. Sports Illustrated, a media giant that could make or curse a career, put out a cover leading into the ’75 season proclaiming he was “proud to be a hero.” But another cover for another baseball preview issue in 1982, after the Dodgers won a World Series, asked if he was “too good to be true” as a “man of principal” who “soldiers on” with all these scandalous tabloid stories pinned onto him.

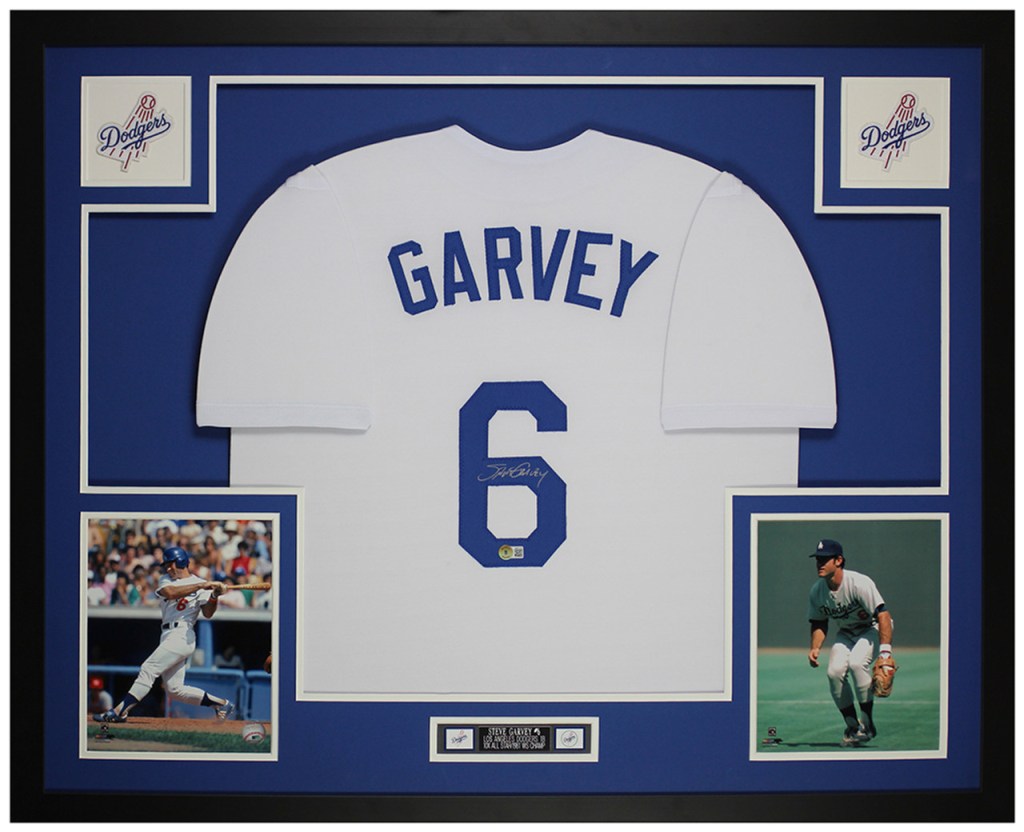

Something the Dodgers’ organization never did for him was noteworthy when San Diego rewarded him by retiring his No. 6 for his brief service.

A middle school in Central California was named after him.

In their 1981 book, “The 100 Greatest Baseball Players of all Time,” authors Lawrence Ritter and Donald Honig included Garvey. Which seemed to mean a Hall of Fame induction was all but secure.

Then, the boy of summer had a fall from grace.

In a 1989 Sports Illustrated feature by Rick Reilly, Garvey’s becoming the butt of national jokes was dully addressed:

“For most of his nearly 41 years Garvey lived at the corner of Straight and Narrow,” wrote Reilly. “In compulsorily hip Southern California, he was hopelessly square: -jawed, -shouldered, -dealing and -thinking …

“Well, boys and girls, stick this in your lunchboxes: Garvey currently is on one side or the other of four lawsuits, having settled two others since Oct. 6. He keeps at least five lawyers in suspenders. In the space of eight months, he had affairs with three women at once, impregnated two and married a fourth. A judge jailed his former wife for contempt of court for not letting him see his kids, and a psychiatrist testified that the kids, who say they don’t want to see Garvey, are suffering from ‘parental alienation syndrome.’ He’s up to his chiseled chin in debt, into the scary seven figures. Two former business associates have sued him.

“Other than that, it has been all apple pie and porch swings.”

Garvey’s response: “Some people have a mid-life crisis. I had a midlife disaster.”

Outlining all the issues Garvey had, Reilly noted that for Christmas 1988, the four women in Garvey’s life all got the same gift: gold pins from Tiffany’s in the shape of three X’s — for kisses. “How was I supposed to know they’d all gang up and compare notes?” Garvey says.

Baseball Hall of Fame writers were comparing notes as well. Did he violate any rules? Do we still have to vote him in based on … this?

In a 2012 piece for ESPN, writer Steve Wulf’s lede leaned into how he imagined Steve Garvey’s Baseball Hall of Fame plaque would look like with its all-caps bronze inscription:

HOLDS NATIONAL LEAGUE RECORD FOR CONSECUTIVE GAMES PLAYED (1,201).

VOTED THE 1974 NL MVP AND SELECTED TO THE ALL-STAR GAME 10 TIMES.

HAD AS MANY AS 200 HITS IN A SEASON SIX TIMES AND

MORE THAN 100 RBIS IN FIVE SEASONS.

BATTED .338 IN 11 POSTSEASON SERIES AND .417 IN THE 1981 WORLD SERIES,

WHEN HIS DODGERS BEAT THE YANKEES IN SIX GAMES.

A FOUR-TIME GOLD GLOVE WINNER, HE ONCE HELD THE RECORD

FOR MOST CONSECUTIVE GAMES AT 1B WITHOUT AN ERROR (193).

Even then, Wulf knew there were footnotes needed.

“The problem with Steve Garvey, though, is that he’s not going to Cooperstown anytime soon, at least not as a member of baseball’s most exclusive and maddeningly incomplete fraternity. ‘I don’t think I was imagining it,’ said George Brett, who is in the club. ‘I know I read a lot of stories about ‘future Hall of Famer’ Steve Garvey’.”

None of this started out very famously.

In 1973, the Dodgers couldn’t figure out where to play Garvey, so they offered their scatter-armed third-baseman to Phillies in a proposed trade for first baseman Willie Montanez. The Phillies declined. The Dodgers saw veteran infielders Wes Parker, Jim Lefebvre and Maury Wills leave the team after the 1972 season, but Garvey’s musical chair scenario had left him standing around as third base prospect Ron Cey was ready for his closeup, and Bill Buckner was primed to replace Parker at first base.

The biggest break of Garvey’s early career occurred in April 1973 when an errant fastball by Houston’s Ken Forsch fractured a bone in the left wrist of Dodgers touted outfielder Von Joshua. More position switches — Buckner went to the outfield; Garvey got some time at first base. Garvey hit .304 in 114 games.

After the Dodgers traded for outfielder Jimmy Wynn in the offseason, Garvey still wasn’t in the ’74 Opening Day lineup. Garvey started the second game, batting seventh. After he hit six homers in April with 20 RBIs and a .321 average, Walter Alston had to find an every-day spot for him. First base. Batting cleanup. By the end of May, he was hitting .338 with 11 home runs and 46 RBI, and the Dodgers were 40-15.

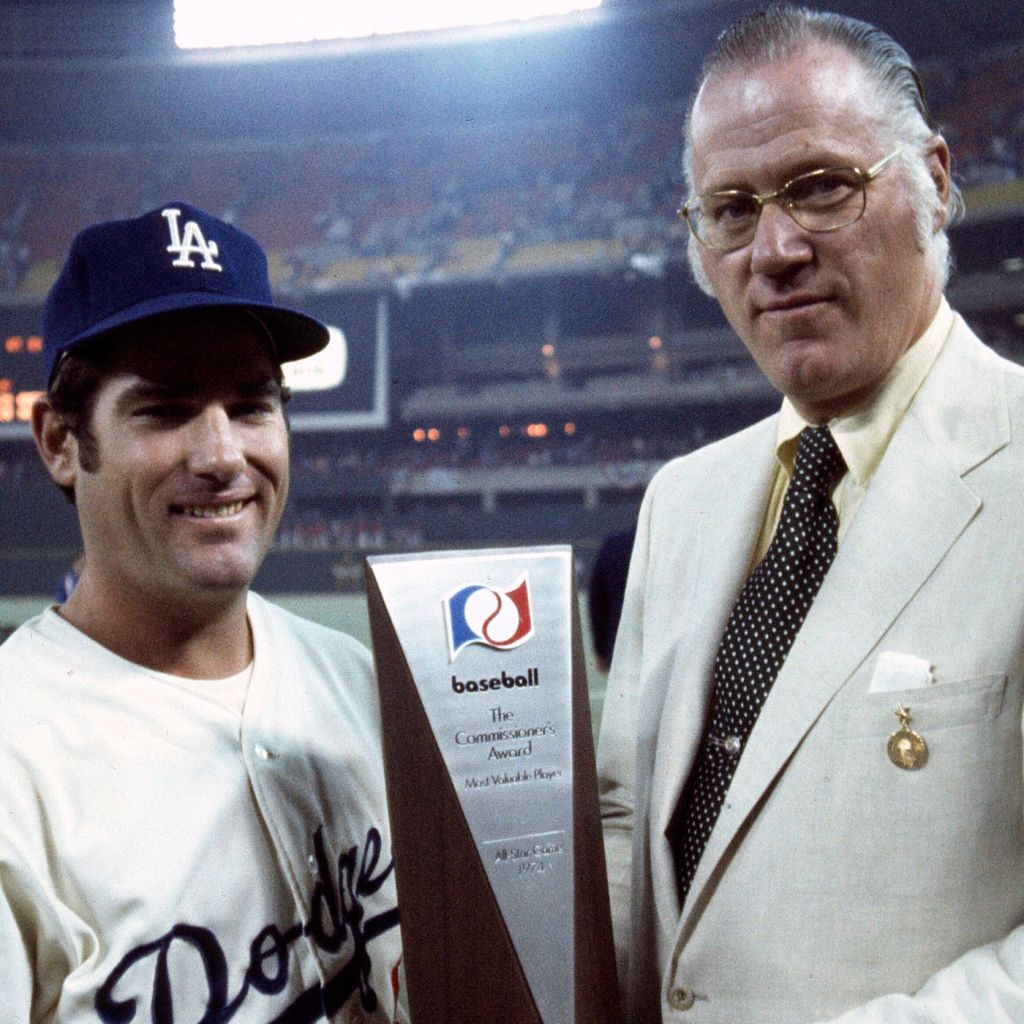

On the pre-printed National League All Star ballot, Garvey wasn’t there. He missed the deadline. So the campaign started to get the 25-year-old as a write-in candidate at first base. It worked. He not only was at game’s MVP, but he ran off with the National League MVP award for the regular season (.312 average 21 HRs, 111 RBIs, 95 runs scored) on the 102-win Dodger team, as well as securing a Gold Glove. The Dodgers reached their first World Series in about a decade.

His salary jumped from $45,000 in ’74 to $95,000 in ’75. From ‘74 through ’80, Garvey started at first base in every All-Star Game, and then made the ’81 team as well as a substitute when the Dodgers were on their way to a split-season World Series title.

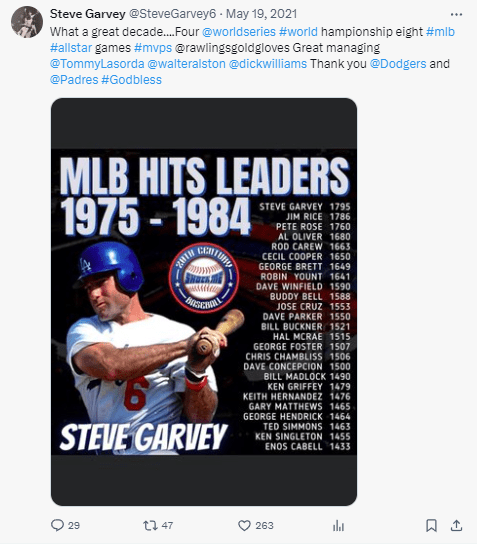

He drove in 100 runs five times. He actually twice won the All-Star Game MVP, was twice the National League Championship Series MVP, and was second in the 1978 NL MVP voting to Pittsburgh’s Dave Parker by hitting .316 with with an NL-best 202 hits.

He also hit .338 in the postseason — and .417 in the 1981 World Series, but was not included in the MVP Award shared by Ron Cey, Pedro Guerrero and Steve Yeager.

The Dodgers decided it was worth letting him go after the 1982 season — a farewell tour after that ’81 title, and the San Diego Padres were more that willing to skim off his fame, and ride his bat into the 1984 World Series.

So what’s not to smile about?

Baseball writer Joe Posnanski may not have included Garvey in his popular 2021 book, “The Baseball 100,” a collection of his essays sizing up the 100 best players in the game’s history, but Garvey made it into his “50 most famous baseball players of the last 50 years.” Posnasnki summed it up this way in a Substack.com post:

I’m not sure that anyone in baseball history has chased fame with the white-hot intensity of Steve Garvey. … It wasn’t enough to become a baseball star. He desperately needed to become a certain kind of baseball star—a hero, a role model, an icon, a little slice of perfection.

He was not very big (listed at 5-foot-10, 190 pounds), and he was not very fast, and he had a weak and erratic arm. His plate discipline was questionable at best; Garvey hardly ever walked. But what Garvey had in abundance—as he showed by refusing to get cut from his high school choir—was extraordinary discipline and unyielding will.

His teammates … (found his methods to chase stats) it selfish and absurd. Garvey once caught them high-fiving each other when one of his carefully timed bunt attempts was turned into an out. (They) for the most part never liked Garvey or understood him. (He wanted to be) the sort of old-fashioned baseball hero that he imagined as a 7-year-old bat boy. He spent every waking hour signing autographs and visiting hospitals and speaking at banquets and representing charities and doing interviews and appearing on television. He was the proudest square in sports, Mr. Clean, didn’t drink, didn’t smoke, didn’t swear, the handsome prince rebelling against the rebels.

If not for the numerous lawsuits that revealed Garvey’s many imperfections—which included numerous paternity claims and testimony from his own kids saying that they didn’t want to see him—Garvey might be in the Hall of Fame.

I do think the off-the-field stuff hurt him, but also a closer inspection of his career showed that many of the accomplishments that launched him into the stratosphere in the 1970s and 1980s do not hold up all that well. His lifetime on-base percentage is an unimpressive .329, he never slugged .500 in any season, and frankly, 200 hits in a season stopped being a touchstone for greatness somewhere along the way. I think these are the bigger reasons why Garvey is not in Cooperstown.

The legacy

In the traditional process of the Baseball Hall of Fame voting, Garvey drew 41.6 percent of the writers’ votes in his first year, 1993. But the closest he ever got to the needed 75 percent was 42.6 in 1995. His eligibility ended in 2007.

He has struck out five times on Veterans Committee finalists ballots over the last 15-plus year. The last try was 2024, when he didn’t get enough votes to have himself mentioned in the top three.

All of this seems rather preposterous for someone who not only completes the Hall of Fame plaque template above, but also received the Roberto Clemente Award. And the Lou Gehrig Award.

Garvey’s own contribution to creating a positive narrative have included several books. “My Bat Boy Days: Lessons I Learned from the Boys of Summer” in 2008 explained how his dad used to drive the Dodgers’ team bus in Vero Beach, Fla., at spring training, giving his son a glimpse at what fame could be.

In Bill James’ book on the Hall of Fame, “The Politics of Glory: How Baseball’s Hall of Fame Really Works,” first published in 1995, he created a point system called the Hall of Fame Monitor to predict status. James concluded Garvey had Hall of Fame numbers in 1997. In James’ “Monitor,” where 100 points based on his weighted stats means a good possibility for the Hall of Fame, and 130 is a “virtual clinch,” Garvey penciled out at 131.

Garvey does have a career WAR of 38.0, 51st all-time for the position, when the average Hall of Fame player is at 64.8. Garvey would then be in a conversion with the likes of Mark Grace, Anthony Rizzo, Bill White and Kent Hrbek.

As writer Ken Gurnick pointed out in 2019 for MLB.com: Detractors point out that Garvey fell well short on the Hall of Fame “automatic” benchmarks of his generation, specifically his lack of 3,000 hits (he had 2,599) and 400 home runs (he hit 272). He never excelled in the categories that matter for WAR, with only two top-10 finishes, peaking at seventh – despite a high-leverage slashline of .335/.369/.505. He never won a batting title or led a league in home runs, RBIs or runs scored. He rarely walked and never slugged more than .500.

The only first baseman with 10 or more All Star Game appearances that aren’t in the Hall: Albert Pujols, Miguel Cabrera (not yet eligible) and Mark McGwire (steroid tainted). For comparison, recently inducted Dodgers first baseman and eight-time All Star Gil Hodges, via the veterans committee, was 43.8, 41st all time.

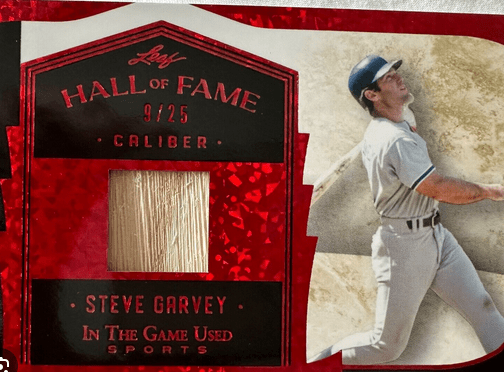

Fame isn’t always calibrated the same way on the Hall of Fame ledger.

When I asked Sports Illustrated writer Jay Jaffe about Garvey’s Hall credentials in 2017, as Jaffe had just come out with a new book called “The Cooperstown Casebook: Who’s in the Baseball Hall of Fame, Who Should Be In, and Who Should Pack their Plaques,” he said:

“I grew up watching him in the 1977 and ’78 World Series. Those Dodgers were the first teams I watched. He was the most popular, visible guy, Mr. All-America, and did all the things that people paid attention to: A .300 average, 200 hits, 20 homers, 100 RBIs, and the famous smile. When you look closer and maybe see he didn’t have a great on-base percentage, wasn’t as great a fielder as we believed, and other numbers don’t quite have the same impact. As a fan of Garvey, I wonder, had the emphasis been more on on-base percentage, maybe he’d approach the game differently, he wouldn’t have cared about getting those bunt singles, he may have been more adaptable. We can only credit him for what he did, and he definitely came up short. This isn’t to slight anyone. To be in this discussion you have to be very, very good to legitimately great.”

In November of 2024, when Garvey was up again for a veterans’ Hall of Fame vote — the state senate election now over — Jaffe updated his ’19 summation yet again predicted Garvey would come up short despite a new set of eyes: He’s never come close to being elected before, and it feels like we’re due for a repeat of that history given the presence of stronger candidates who have come much closer to being enshrined. It’s difficult to see him as more than a bystander on this ballot, albeit one who could play the spoiler by siphoning off a few votes.

When I compiled a tribute book to Vin Scully that the University of Nebraska Press released in May 2024, Garvey was one of the 67 contributors. A phone conversation resulted in his essay, which included:

Consistency in life is maybe the great virtue any of us could have. Life can be so challenging but you have to be able to take anything that comes to you in life and be able to handle it with dignity and honor, and learn from it. We are infallible. We make mistakes. We just try not to make the same mistake twice. We all strive for grace. We can achieve it in a variety of different ways and to different degrees.

When I do public speaking, I try to emphasize it’s not what you are – ballplayer, announcer, bus driver – but what do believe in? What do you stand for? How are you trying to accomplish that in your life?

So perhaps the former Los Angeles Dodgers will never be a Washington Senator. But the pursuit was worth watching for history’s sake.

More Garvey miscellany:

== Garvey told us once about the numbers he wore:

“I wore No. 10 in baseball at Michigan State — and No. 24 as a defensive back on the football team. But No. 6 was just what I was given with the Dodgers. I knew No. 6 was Carl Furillo (in Brooklyn from 1946 to ’57, then in Los Angeles from ’58 to ’60) and then Ron Fairly (who had it from 1961 through 1969 until Garvey had it). When I was growing up, I really admired Al Kaline and Stan Musial, both whom wore No. 6. I felt like I was just like them when I started becoming the steward for it. Then it was kind of funny to see the Dodgers give it to Joe Torre. At least the Padres retired it for me, and that was quite an honor.”

That Padres ceremony came in April of 1988, the first month after he was done as an active player. It was a way to remind fans of his walk-off Game 4 homer in the ’84 NLCS against Chicago’s Lee Smith that rescued their postseason at the old Jack Murphy Stadium. He was the first player to have his number retired in franchise history. Although some have called it the “most iconic moment in San Diego sports history,” others see the retirement as a somewhat rash decision that can’t be undone.

The Dodgers, patiently, still haven’t retired No. 6 — yet Garvey has been inducted into some team purgatory of greatness with Orel Hershiser, Manny Mota, Maury Wills and a few others we can’t readily recall.

After Garvey went to San Diego via free agency following the 1982 season, the Dodgers didn’t give it out for more than 20 years, perhaps waiting to see what would happen. Torre wore it as the Dodgers manager from 2008 to 2010, winning two NL West titles, because he had worn it for 12 years with the New York Yankees. Among others who have worn it: Jolbert Cabera, Brent Mayne, Jason Grabowski, Kenny Lofton, Tony Abreu, Aaron Miles, Jerry Hairston, Darwin Barney, Charlie Culberson, Curtis Granderson, Brian Dozier, Trea Turner and David Peralta. In 2025, it was given to South Korean rookie second baseman Hye Seong Kim (or, Heyseong as it sometimes appears, even though the back of his jersey reads H.S. Kim).

We’re not even sure who Darwin Barney is.

== On the SABR baseball cards blog site, long-time collector “JasonCards” had this post in August of 2023:

Growing up in 1970s Los Angeles, there was never really a question or a choice when it came to my favorite player. Steve Garvey was Dodger baseball. Really, he was even bigger than that. He was God, country, and apple pie. He was Baseball itself.

The truth is Steve Garvey was my favorite player before I’d ever seen a ballgame, held a bat, or carried around his cards in my pocket. If you grew up when I did and grew up where I did, you loved Steve Garvey. That’s all there was to it. … (In school), one could be kind, smart, or funny but at the end of the day Steve Garvey cards were the true currency of cool.

He then goes on to discuss the top 10 Garvey baseball cards issued — including our favorite, the landscape shot of him on the Topps #575 of 1974, where he’s listed as “3B-1B,” and later brought back in a 2016 Topps set.

In 2019, prior to the Veterans Committee Hall of Fame vote, “JasonCards” also made his case for Garvey’s induction:

“If a formula keeps telling you Steve Garvey belongs in the Hall of Fame as much as (or less than) Jeff Pfeffer, the fault may not be with Steve Garvey but with the formula. The man was a perennial all-star and fan favorite who led his teams to five pennants in eleven years, none of which they would have won without him. Along the way he excelled in all the statistical categories that the baseball world cared about at the time.

“I know the ‘intelligent fan’ would rather visit the plaque of a guy who walked a lot or turned .400 teams into .450 teams, but the dumb guy writing this will walk right past the busts of enshrined immortals the likes of Nestor Chylak, Ned Hanlon, and Bud Selig to the overdue plaque of Steven Patrick Garvey, Hall of Famer… or if the Committee passes on Garvey once again, hey, I guess my whole childhood was a lie, that’s all.”

They passed. Again, it wasn’t in the cards.

But we do have this postcard from the edge to admire:

Who else wore No. 6 in SoCal sports history?

Make a case for:

Ron Fairly, Los Angeles Dodgers first baseman/ outfielder (1959 to 1969), California Angels DH (1978):

The Long Beach Jordan High standout made his mark at USC in one season — in 1958 when he hit .348 with nine homers and 67 RBIs as a sophomore center fielder on the Trojans’ College World Series title team. He was an All-District 8 selection that season. That led to him signing with the Dodgers and after two brief minor-league stops getting a call-up as a 19 year old later that summer — he hit .283 in 15 games. His 12 seasons with the Dodgers included being on the 1959, ’63 and ’65 World Series teams. He hit .379 with two homers and six RBIs in the ’65 Classic, playing all seven games. The Dodgers traded him to Montreal in June of 1969 in order to get Maury Wills back, along with Manny Mota.

His final season in Anaheim at age 39 saw him get into 91 games and hit .217 with 10 homers. Fairly made a second career as a broadcaster, starting at KTLA-Channel 5 and broadcasting Angels games. His 2018 autobiography “Fairly At Bat: My 50 years in baseball, from the batter’s box to the broadcast booth,” came out a year before his death in 2018 at age 81 in Indian Wells. He was inducted into the USC Athletic Hall of Fame in 1997.

Carl Furillo, Los Angeles Dodgers outfielder (1958 to 1959):

A case can be made that Furrillo was the Dodgers’ franchise all-time best right fielder. That takes him back to 1946 and his first season in Brooklyn, rather than the just last two years he had in Los Angeles at the Coliseum. It was Furillo’s infield single in the 11th inning of the final game of the ’59 season allowed the Dodgers to outlast Milwaukee, clinch the NL pennant and send them to Chicago to open the World Series against the White Sox. The Dodgers released Furillo during the 1960 season and he moved back east. He helped install the elevators in the World Trade Center buildings.

Joe Torre, Los Angeles Dodgers manager (2008 to 2010):

The Dodgers retained his services after the Yankees ownership decided his leadership had run its course after 12 years, four World Series titles and six AL pennants – which would eventually be enough to land him in the Baseball Hall of Fame. Torre made sure to bring manager-in-training Don Mattingly with him so when he departed for good after an 80-82 season, last in the NL West, there would be a succession plan. The Dodgers won the NL West in his first two seasons with a Manny Ramirez injection but lost in the NLCS twice in a row to Philadelphia.

Mark Sanchez, USC football quarterback (2006 to 2008):

The top high school quarterback in the nation from Mission Viejo High (wearing No. 6) moved onto to USC, sat out as a redshirt in 2005, and moved in and out of the starting lineup his first two seasons. After a junior season where he threw for 3,207 yards and 34 touchdowns, leading the team to a 12-1 record and a Rose Bowl win over Penn State, Sanchez announced he wasn’t returning for his senior season, which seemed to take Trojans head coach Pete Carroll off guard. Sanchez was the first USC quarterback to leave early since Todd Marinovich in 1990. The New York Jets took him with the fifth overall pick.

Sue Enquist, UCLA softball (1975 to 1978):

Before she became a Hall of Fame coach with the Bruins over a career that spanned a 30-year involvement in the program, Enquist was the first in the school’s history to receive a softball scholarship when the program started her freshman year in 1975. The All-American center fielder hit .391 her senior season leading the team to a 31-3 record and its first national title — this was four years before the start of the NCAA, so it was under the Association of Intercollegiate Athletics for Woman (AIAW) banner. The San Clemente High standout hit a five-game championship-tournament best .421 in Omaha, Neb., as one of only four seniors on the team — including Denise Curry, the All-American basketball player for the Bruins. Enquist established the UCLA career batting average record with a .401 mark, which stood for 24 years. Enquist’s No. 6 jersey was retired in 2000, joining Lisa Fernandez (16) and Dot Richardson (1). With a degree in kinesiology, Enquist was an assistant Bruins coach starting in 1980, then co-head coach in 1986, would eventually succeed Sharron Backus as the head coach in 1997, winning 11 titles as a player and a coach before she retired in 2006 with a 887-175-1 (.835) record. She also has experienced 1,314 wins in her Bruin softball career as a player and coach, combined. Enquist, who also surfed professionally from 1979-81, was part of the coaching staff that prepared the U.S. softball team to win gold in 1996 during the sport’s inaugural Olympic tournament. Her motivational speaking and leadership continued to influence the success of the U.S. women’s national volleyball team (coach by former UCLA standout Karch Kiraly) during the 2024 Summer Games in Paris.

Anthony Rendon, Los Angeles Angels third baseman (2020 to present):

The Angels gave Rendon a seven-year, $245 million deal after his notable participation in the Washington Nationals’ 2019 World Series run. This was a bargain that Rendon’s agent, Scott Boras, arranged as a consolation prize to owner Artie Moreno after he couldn’t get enough coin together to land his other client, heralded pitcher Garrit Cole. Moreno thought he was getting someone credible to hit in the lineup behind Mike Trout, coming off a season where he led the MLB with 126 RBIs to go with 34 homers and a .319 batting average. It never came close to happening. In his first four seasons with the Angels, Rendon averaged about 50 games a pop, and hit a combined 22 home runs (one of them even on a lark when he batted lefthanded), drove in 111 and amassed a .249 batting average while drawing a $128 million of that salary. Interviewed in spring training of ’24, Rendon confessed that baseball has “never been a top priority for me. This is a job. I do this to make a living. My faith, my family come first before this job. So if those things come before it, I’m leaving.” After the the 2025 season, where Rendon didn’t make one appearance and is still owed $38 million for 2026, the Angels started to construct an exit package for him. All the while, the Rendon done deal continues to be discussed as one of the ugliest deals ever given to a player in MLB history. Since his megadeal with the Angels, he has accumulated a 3.7 fWAR. (And on that list highlighted, Rendon actually comes in a notch above the one the Angels gave to Trout.)

Marc Wilson, Los Angeles Raiders quarterback (1982 to 1987): After his first two years in Oakland, Wilson made the move to L.A. with the Raiders and assumed the starting role in 1984, posting his best season when he had a 11-2 record as a starter in 1985 as Jim Plunkett’s successor.

Eddie Jones, Los Angeles Lakers guard (1996-97 to 1998-99):

Made a starter as a rookie, he played his first two seasons wearing No. 25 (1994-95 to 1995-96) until the Lakers needed to borrow it for honoring Gail Goodrich as he went into the Hall of Fame. Taking No. 6 for two-plus seasons, Jones made two Western Conference All-Star teams before he was traded in the 50-game shortened season of 1999 to Charlotte (with Elden Campbell) to get Glen Rice, B.J. Armstrong and J.R. Reid. Jones had the best month of his career in November of 1997, when the Lakers won their first 11 games of the season by an average of nearly 16 points, and he was the NBA’s Player of the Month after scoring 21.1 points per game and shooting nearly 57 percent from the field, including 44 percent from 3.

Steve Timmons, USC men’s volleyball (1980 to 1982):

With the iconic redheaded flat top, Timmons came out of Newport Beach and led the Trojans to the 1980 NCAA title. He earned first-team All-American honors in 1982 and was a second-team selection in 1981. The Trojans reached the final four in each of Timmons’ three seasons. He ended up marrying Jeanie Buss for a time, won two Olympic gold medals and a bronze in the indoor game, co-founded Redsand beachwear, and played on the AVP Pro Beach circuit with Karch Kiraly from 1986 to 1994.

Eric Byrnes, UCLA baseball outfielder (1995 to 1998): A .331 career batting average with 75 doubles has stood as Pac-12 Conference records. Byrnes was an All-Pac-10 honoree in both 1995 and 1997 and was a key bat on the UCLA squad that went to the College World Series. Byrnes left UCLA also tops in runs scored (235) and hits (326) to go with 48 homers and 20-3 RBIs, and was inducted into the UCLA Athletic Hall of Fame in 2013.

Johnny Hekker, Los Angeles Rams punter (2016 to 2021): One heck of a weapon in the Rams move from St. Louis to L.A. (he started with the franchise in 2012), a four-time Pro Bowler led the league in punt yards (4,680 for an average of 47.8) and a long of 78 in ’16. That season he also set an NFL record with most punts inside the 20-yard line: 51. In Super Bowl LII against New England, he set a game record with a 65-yard punt (punting nine times in the Rams’ 13-3 loss). Leading up to the Rams’ Super Bowl LVI win, Hekker planted five punts inside the 20 against Arizona in a 34-11 wild-card victory. Then the Rams released him.

Eric Kendricks, UCLA football linebacker (2011 to 2014), Los Angeles Chargers linebacker (2023): Always odd to see a linebacker wear this number, but Kendricks did so in four years at UCLA and one with the Chargers, as a team captain who started 14 games and was second on the team with 117 tackles. He signed a two-year, $6.75 million deal after eight seasons in Minnesota. Then the Chargers released him.

Have you heard this story:

Adam Morrison, Los Angeles Lakers forward (2008-09 to 2009-10):

Just 39 games played. No starts. And two NBA titles to show for it. Maybe the 2006 Naismith and Wooden Award finalist out of Gonzaga really did lead a charmed life, having two final NBA seasons that ended in championships. When the Lakers held a ceremony to honor the late Kobe Bryant with a statue outside of their home arena, former Lakers coach Phil Jackson told a story about the time ABC’s Jimmy Kimmel had Bryant and several Lakers players on his late-night show following their 2010 NBA title, and showed some highlight clips — some of which made fun of the fact Morrison was often just in street clothes sitting on the bench. Bryant went along with the joke, but also said on the show: “Let me just say that, you know, that’s a testament to our team, honestly, because Adam can really play. Like, he can really, really go. And for him to take a step back and to do things like that really helped us get to that championship level.” The audience applauded. Jackson finished the story: “Kobe said, ‘Don’t make fun of Adam Morrison. He’s one of our teammates. He puts in the work. He may not get to dress, but he puts in the work and he’s part of our team.’ That’s when I was the proudest of Kobe.” Would you consider Morrison one of the great NBA busts? Depends on how you define it.

Charlie Culberson, Los Angeles Dodgers infielder (2016): In a season where the infielder played only 34 games, the one homer he hit — a walkoff on Sept. 25, 2016, during Vin Scully’s final home broadcast, gave him a niche in team history. He came back for the 2017 season wearing No. 37.

Bronny James, USC basketball guard (2023-24): Taking the No. 6 his father is wearing for the Lakers, the 6-foot-4, 210 pound guard from Sierra Canyon High had “elite basketball instincts and toughness with the ability to score from anywhere on the court,” according to his team website bio. He spent one year with the Trojans, 25 games, starting six, averaging 4.8 points a game, and went into the NBA Draft. Where the Lakers took him in the second round. And gave him No. 9.

And where is the Los Angeles Lakers / LeBron James’ homage to No. 6? We think that’s been covered here.

We also have

Roger Repoz, California Angels outfielder (1967-1972)

J.T. Snow, California Angels first baseman (1993 to 1996)

Trea Turner, Los Angeles Dodgers shortstop (2021 to 2022)

Bill Buckner, California Angels designated hitter (1987 to 1988)

Sean O’Donnell, Los Angeles Kings defenseman (1994-95 to 1999-2000; 2008-09 to 2009-10)

Cody Kessler, USC quarterback (2012 to 2015)

Anyone else worth nominating?

Don’t forget Chuckie Brauer #6 on the Fullerton Senior Little league Phillies in 1965. He pitched and played third base while batting .323.

On Thu, Feb 15, 2024 at 9:07 AM Tom Hoffarth’s The Drill: More Farther Off

LikeLike