“Leave While the Party’s Good:

The Life and Legacy of

Baseball Executive Harry Dalton”

The author:

Lee Kluck

The publishing info:

University of Nebraska Press

392 Pages; $39.95; released June 1, 2024

The links:

The publishers website

At Bookshop.org

At Powells.com

At Vromans.com; at Walmart; at BarnesAndNoble.com; at Amazon.com

The review in 90 feet or less

Thirteen members make up the league of unfortunate gentlemen who agreed to serve as general manager for the historically cursed Los Angeles/California/Anaheim/Los Angeles Angels of Anaheim, including prior to the franchise’s birth in 1961.

Which one generally managed to make the greatest impact?

Bill Stoneman, if only because of the fact he was in the chair during the Angels wild-winding wild-card run to the 2002 World Series title, is the quick-wit choice. He arrived three seasons before that improbable title scramble. He lasted five more afterward before he pooped out at age 63. Between his term of 1999 and 2007, the Angels also made the playoffs as the AL West champs in ’04, ’05 and ’07. It was Stoneman who hired Mike Scioscia as the team’s 20th manager in 2000, and the former Dodgers catcher lasted more than 3,000 games, and was the ’02 and ’09 AL Manager of the year. In creating the 2002 roster, Stoneman pulled the trigger on the trade of Jim Edmonds to St. Louis for Adam Kennedy and Ken Bottenfield, and it worked. Stoneman signed Scott Spiezio, David Eckstein and Brendan Donnelly. Two years after the championship, he landed future Hall of Famer Vladimir Guerrero. He drafted Jered Weaver, Ervin Santana, Howie Kendrick and Casey Kotchman. Stoneman, a former big-league pitcher himself, rarely messed around with in-season trades.

Even then, he wasn’t done. Stoneman made a comeback as the interim GM in the middle of the 2015 season after Jerry Dipoto’s rocky data-driven three-and-a-half-season time ended, following the heralded signings of Albert Pujols and Josh Hamilton between 2011 and ’15.

Tony Reagins, Stoneman’s immediate successor after the 2007 season, was the franchise’s first and only Black GM. He may have only lasted four seasons, but included in that was drafting Mike Trout in 2009, at No. 25 overall, an outfielder from Millville High in New Jersey. (For what it’s worth, the pick came after Reagins took another outfielder, Randal Grichuk at No. 24 from Lamar High in Texas). Reagins also signed Torii Hunter and traded for Mark Teixeira and Dan Haren. He didn’t wear well the signings Vernon Wells and Scott Kazmir.

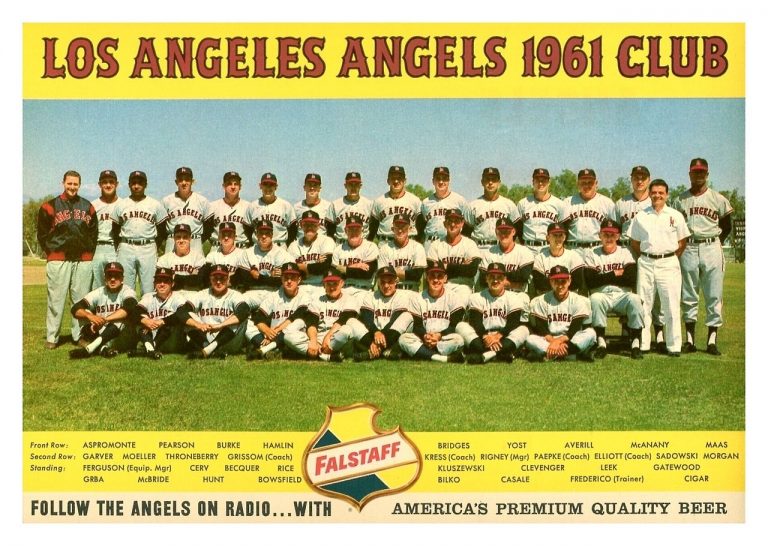

Fred Haney, the former Hollywood Stars and Los Angeles Angels broadcaster in the Pacific Coast League, and the GM for the 1957 World Series champion Milwaukee Braves, was the Angels’ first deal maker. He first had to navigate the dispersal draft logistics and then find a roster that could perform in the old Wrigley Field, then Dodger Stadium, then the new Angel Stadium. Somehow they had a 70-win season in ’61, still a record for expansion teams. Aside from shaping the first rosters, Haney’s success was relevant in finding Jim Fregosi, Dean Chance, Leon Wagner and Lee Thomas.

After those three, we’ve got, in no particularly effective order:

Buzzie Bavasi (1977 to 1984) and his son, Bill Bavasi (1994 to 1999), both something of a buzz kill. The elder Bavasi’s time with the team as it went to two post-season appearances under his watch. It wasn’t really because of him, but in spite …

Billy Eppler (’15 to ’20) may have overseen five losing seasons and had another year on his contract when he was let go, and he was in change when Scioscia left and decided Brad Ausmus could handle the spot as the manager. Yet, Eppler did a lot of groundwork recruiting of Shohei Ohtani, and was in the team’s toll booth when the Japanese star arrived, helping keep Trout at bay.

No-Frills Mike Port (1984 to 1991) was really just an extension of the first Bavasi regime and relied on a farm stocked with Mike Witt, Chuck Finley, Wally Joyner, Devon White and Gary Pettis, and then drafted Edmonds, Tim Salmon, Garret Anderson, Troy Percival and Jim Abbott.

Whitey Herzog (1993 to ’94) was thought to bring some name value but was otherwise a white-hot mess, loading up the team with former Cardinals has-beens. Lump him in with Dick Walsh (’68 to ’71), Dan O’Brien (’91 to ’93) and the current Perry Minasian (since 2020), who may be on borrowed time as well.

Then there was Harry Inglis Dalton.

Dalton agreed to come to Southern California in October of 1971 as the hand-picked choice of owner Gene Autry, basically lured away as a free agent from the then-successful Baltimore Orioles, a place he thrived from 1966 to ’71.

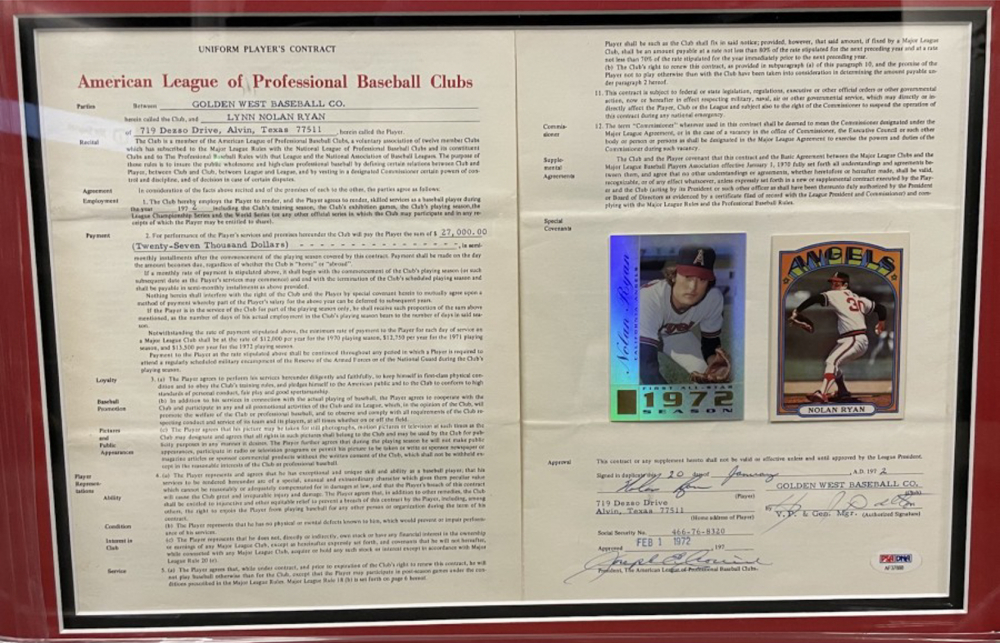

Within weeks, Dalton had the gumption to trade Fregosi to New York for Nolan Ryan. It still haunts Mets fans.

When Dalton was let go by October of 1977 in favor of Bavasi Sr., Ryan would also eventually leave as well. It was no coincidence.

Dalton and Ryan were linked. Gentlemen who had respect for each other, from start to finish.

Now connect the dots: If Autry wasn’t so impatient in thinking “The Dodger Way” was going to be his template for winning with the Angels, convincing himself to add on former Dodger thinkers, Buzzie Bavasi wouldn’t have been brought into second-guess Dalton, and Ryan wouldn’t have been forced to go to free agency because of Bavasi’s subsequent faulty financial planning.

And without Dalton dialed in with his his effective free-agent deals –from Joe Rudi to Don Baylor to Bobby Grich — the Angels would have completely disappeared in the Dodgers’ shadow in the 1970s. The Dodgers may have succeeded in winning the NL titles in ‘74, ‘77 and ‘78 with their home-grown talent, but they couldn’t pull off the big-name acquisitions that Dalton did in Anaheim (and they lost to the free-agent-loaded New York Yankees in the final two runs, finally beating them in ’81). Yet Autry still believed in the Dodgers’ mystique, scooped up ex-employees for the front office and crushed Dalton’s work. So he went to Milwaukee and Bud Selig and helped the Brewers eliminate the Angels in the ‘82 ALCS. Dalton swapped out Buck Rodgers for Harvey Kuenn as the manager two months in, the “Wall Bangers” outlasted Baltimore for the AL East title by one game and, even thought the Angels won the first two games of the ALCS, Gene Mauch’s team squandered the last three, as Don Sutton, who Dalton got at the trade deadline from Houston, throttled them in Game 3. Fred Lynn of the Angels, who Buzzie Bavasi got in a ‘80 trade, was the series MVP. But it didn’t matter.

That, at the very least, is how we get a better read on things after enjoying a trip through this well-researched, well-developed bio about a baseball man who, all things considered, could have his Baseball Hall of Fame resume re-examined.

Dalton’s 40-plus years as a general manager that started in Baltimore and would wind up polishing up Milwaukee’s Brewers between ‘78 and ‘91, but the sweet spot of the book for Angels’ historians will be between Chapters 8 and 12, which span Dalton’s impact on the team during the impactful free-agent flurry.

The 70 pages are enough to document what Dalton did in the new era of players going here, there and everywhere — a reflection on how Dalton came to the Angels in the first place.

The bottom line was that Dalton kept positive relationships and diffused tepid situations, especially late in his tenure with Autry. Some of the revelations here include the rumor that Dalton was going to bring Earl Weaver with him to manage the Angels in ’71, but ended up going through a series of trial-and-error skippers that seemed more to define his place in the media chronicling the team.

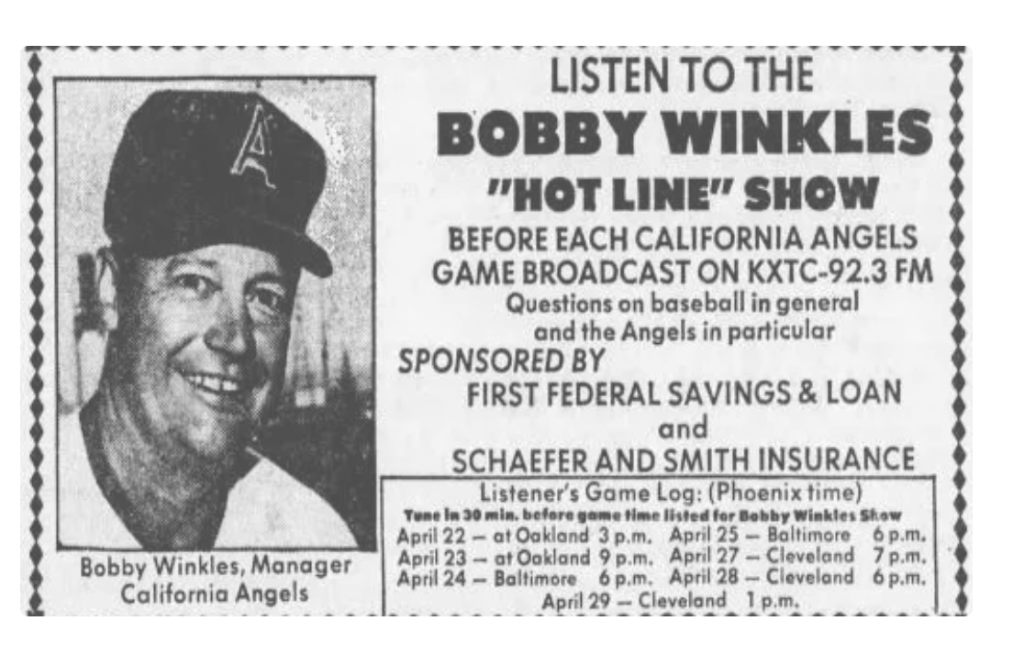

In ’71, the Angels managers had only numbered two — Bill Rigney (’61 to ’69) and Lefty Phillips (’69 to ’71). Dalton took a chance on Del Rice for one year, extracted Bobby Winkles from the college game (’73-’74), passed on Herzog as a temp in ’74 in favor of the available Dick Williams (through ’76) and then tried Norm Sherry and Dave Garcia. Five managers didn’t really manage much stable or stellar, but in effect, they were also trying to find their place in the game amidst big-name player movement. Patience wasn’t what it used to be.

Dalton understood the essence of what free agency could bring and how it could be integrated in a roster with a team improving by being prudent with spending and negotiations.

Plus, Dalton liked the idea of where the Angels were going a decade into their existence, and the idea of moving his family to California as he was always a family-first individual. That’s also illustrated in the photo section that shows him as a tireless worker who never let himself get too far from a payphone, even on a family trip. It’s incredible to think he got all this accomplished in a pre-cell phone/Internet period.

Dalton’s influence on the franchise was unimpeachable (and yes, he was friends with local OC resident Richard Nixon) and makes you wonder what would happened if Autry hadn’t been so quick to let him move on. The team’s win-loss record over Dalton’s tenure isn’t dazzling, nor is it his fault (as also documented in Dalton’s SABR bio). It actually could have been much worse.

But here, Dalton, who died nearly 20 years ago at age 77 from Lewy body disease, gets his due. A career in full with some time and history to ponder makes it that much easier to understand what Kluck has done here there a myriad of research, family interviews and talking to those — his “gang” — who went through it all with Dalton.

Author Q&A

We are grateful to have this correspondence with Lee Kluck, who presented the groundwork for this book at the 2023 NINE convention in Scottsdale, Ariz., attended by some of the Dalton family:

Q: How did Harry Dalton, of all the baseball people available, ignite your desire to do a book? His Wisconsin connection?

A: I grew up a fan of the Milwaukee Brewers of the mid-1980s. They were still really competitive in the decade after their appearance in the World Series in 1982. I knew I wanted to write a book, but I was unsure of the topic. However, when I thought about the teams I watched as a kid and applied the lens of a professional historian with over thirty years’ distance, I wondered how the Brewers could stay good despite impending financial difficulties that would hit the team beginning in 1993. What I came up with was that Harry Dalton and the scouts and advisors around him were really good at their jobs. The original period of my book was going to be 1983-1992. The scope of my book changed when I realized that Harry’s decisions in Milwaukee were shaped by his time in Baltimore and California, and you needed to tell the whole story to understand Milwaukee.

Q: The Dalton who we often read about in Southern California might have been framed more as the GM who couldn’t pick a manager that fit well more than the roster he constructed. He was thinking outside the box with Bobby Winkles, but it kept cycling through others, unknown and well known. Do you think the criticism was fair?

A: I think the press characterization of Harry as “Hangman Harry,” who went through managers, is accurate but simplistic. Part of his inability to find a manager who fit with the roster was because ownership could not understand that it would take years to build what Dalton oversaw at the end in Baltimore. Autry was so concerned with competing with the Dodgers (and emulating them) that it forced Dalton to win before they were probably capable. Still Harry tried to win while building, and when it came to managers, he couldn’t find someone who would be accepted by the veterans and patient enough to work with the kids that Harry was drafting.

Q: What’s your take on how Nolan Ryan got along with him, in relation for what also seemed to be his intent to please owner Gene Autry?

A: I once asked Harry’s daughters and his late wife Pat who Harry’s favorite players were to work with and who their favorite players were to interact with. They all listed Nolan Ryan right at the top of the list. Nolan and Ruth are revered and loved by the whole family. Harry and Nolan fostered a good relationship on and off the field because of a shared understanding of loyalty. Harry loved players who gave him everything they had, and players loved Harry because they knew he appreciated their efforts and that he would treat them as people. When I talked to Nolan — which he did because he and Ruth liked Harry and Pat as people — he quickly told me that he would not have become the pitcher he became if Harry Dalton had not allowed him to grow into his talent. He also said he left California because Buzzie Bavasi was not Harry Dalton. That is to say, while Buzzie wanted to tell people how bad they were even when they weren’t, Harry would never denigrate someone to save a dollar and Nolan appreciated that. Finally, I think it is important to remember both men were family-forward. First and foremost, they were parents who would do anything for their kids and their wives. This provided a huge common ground.

Q: What was your most surprising revelations about his time with the Angels? Some trades not made? Rumors of him maybe bringing Earl Weaver with him?

A: I think my biggest surprise vis-à-vis Harry and the Angels was that before you even looked at the moves Dalton made or didn’t make, you had to understand that the Dodgers were Gene Autry’s white whale. He wanted to be them, and he was willing to hire anyone he felt could reproduce what Walter O’Malley had and acquire any player that would bring a modicum of that success. This phenomenon became so pervasive that it ultimately forced Harry to leave his job when Buzzie Bavasi convinced Gene that he needed minding. On some level, I don’t think Harry ever understood the hold the Dodgers had on the Angels staff and fans. He even replied to a reporter who asked him how his move might affect the Dodgers; Harry asked if he knew they were in the other league. Still, even with that as the background, I think it’s important to remember that people around during his tenure believed that Harry was part of why the Angels had so much success in 1978. This included Gene Autry and Nolan Ryan. Ryan went as far as to say that the Angels were successful later because of Harry’s work. As for Autry, in 1978, when the Angels finally won, Gene sent Harry a letter thanking him for doing the things that got them over the top. They always had a good relationship.

Q: You got such great access to his notes and documentation of things. Was he planning to do his own memoir?

A: I got extremely lucky with this book in terms of sources. If it were up to Harry, he would have never said a word about his career or legacy in public, and he hardly ever did so in private. He just didn’t see what he did that was so special. As I put it, he didn’t care about being Harry Dalton. That being said, he saved everything, and his family, with the help of Dan Duquette, who worked for Harry in Milwaukee, did the same. They then donated everything to the Giamatti Research Center in Cooperstown. This information was invaluable because it gave me a framework for each phase of Harry’s career. From there, I lucked out again because Harry’s family provided me any assistance they could generate. This generosity was born out of their love for their father and husband, the importance of Harry’s career in their mind, and my diligence in getting things right. Finally, people talked to me because Harry Dalton was good to them, and they wanted to return the favor. It did not matter if it was a Hall of Famer — I talked to four players, two execs, and five media members — people who enjoyed their privacy, or those in baseball with busy schedules; they wanted to help Harry by helping me. That is the kind of person Harry was.

Q: All in all do, you believe you made a Hall of Fame case for him? What other GMs maybe does he compare best to?

Although his career in California was not successful on the field, I believe that the totality of the winning he did, the mentorship he provided to successful young executives like John Schuerholz, Dan Duquette, Bruce Manno, Pat Gillick, his association with great managers like Earl Weaver, and the work he did to make the game a better place, makes him a Hall of Famer and those who knew him in the game agree. I will share two examples. Bud Selig called Harry the best baseball mind of their generation. Any time the owners had an existential question on how to make the game better, they asked Harry. Finally, Earl Weaver said in a letter read at Harry’s celebration of life that he couldn’t understand why Harry wasn’t there when he was inducted into the Hall of Fame. Because without Harry Dalton, there was no Earl Weaver. As for what GMs he compares to, in terms of winning, he was Pat Gillick or John Schuerholz before they were. His teams won a lot, and people wanted to run their offices like his. Winning was only part of it, however. Harry was smart. If he came along today he would be Theo Epstein or Billy Beane. He would be a celebrity because no one thought about baseball like he did and paired it with winning baseball and a willingness to teach others. Finally, I think Harry would be appreciated because, for all his skills, he was well-liked and thought about the larger world. He is a great ambassador for the game in every regard.

Q: Once again, where did the title come from?

I asked the girls and Pat if Harry had a favorite saying. They all agreed that Leave While the Party’s good was it. He always believed that it was a good philosophy to get out early before it was too late. It didn’t matter if the girls were going out or he was making a trade.

How it goes in the scorebook

Party hearty, Daltons. A Cooperstown soiree may be in the works.

This Harry was not a spare. He’s worthy of a baseball coronation.

As bios can be done these days to shine a new light on those overlooked or under appreciated in the game — mostly players or managers or owners — this can refocus on the execs and GMs who used the resources of the time to make decisions as well as trusting their instincts. It was important in Dalton‘s day to do that with personal contacts and establishing trust and so reliant on new data. Being honest and fair. His background as a journalist long ago gave him that perspective and ethical foundation.

His eyeballs were plenty sharp to not only create the great teams of Baltimore and later in Milwaukee, but also shape the Angels at a time when they needed different managers and have the blessing of Autry’s wallet to pursue things.

The Angels should consider putting him first into their own Hall of Fame — with Stoneman, for sure, and even Haney. But if the only thing it says on Dalton’s plaque was that he was the one who gave up Fregosi for Ryan, it’s now shortsighted and incomplete. This book completes any debate over Dalton’s due diligence and links him more to the groundwork he laid.

More to ponder:

== The site’s official Facebook page at this link.

== A review by Charlie Bevis at Bevis Baseball Research linked here.

If any of these former GMs are available or even alive (not a job requirement), the Angels should seek them out.

On Tue, May 14, 2024 at 7:04 AM Tom Hoffarth’s The Drill: More Farther Off

LikeLiked by 1 person