“The Last of His Kind:

Clayton Kershaw

And the Burden of Greatness”

The author: Andy McCullough

The publishing info: Hachette Books; 368 pages; $32; released May 7, 2024

The links: The publishers website; at Bookshop.org; at Powells.com; at Vromans.com; at TheLastBookStoreLA; at {pages: a bookstore}; at BarnesAndNoble.com; at Amazon.com

The review in 90 feet or less

Fifteen years after it came out, the documentary “Bluetopia: The L.A. Dodgers Movie” found its way to our BluRay machine for a trip down memory lane recently.

Released in 2009 as a way to celebrate the franchise’s 50th year in Southern California, chapters and vignettes are weaved together to convey explanations as to why so many are connected to the team’s existence — journalists and broadcasters, tattoo artists and attorneys, cancer patients and celebrities, former gang inmates involved in Homeboy Industries as well as the founding spiritual leader, Fr. Greg Boyle.

It also covers the 2008 season in full: Manager Joe Torre’s team running toward the NL West title, the acquisition of Manny Ramirez, the McCourts influence, Ned Colletti’s roster built around Russell Martin, Matt Kemp, Andre Ethier, Chad Billingsley and Jonathan Broxton.

And there’s also the debut of a 20-year-old rookie named Clayton Kershaw.

The segment on Kershaw’s first game on May 25 on a Sunday afternoon at Dodger Stadium against the St. Louis Cardinals leans heavily into Vin Scully’s description and how the moment was met.

“Fastball, got him swinging!” Scully says when Kershaw fans leadoff man Skip Shoemaker (a future Dodger teammate), “and down below (in the stands) we watch his mom applauding.”

Now, all things considered, so very sweet to see.

When the Cards’ No. 3 hitter (another future Dodger teammate) lines a double down the left field line, Scully admits: “Kershaw is baptized by Albert Pujols, and that figures.”

Kershaw ends the inning with a very slow curveball to record a strikeout, and after the game, the cameras capture Kershaw with his family members — his future wife Ellen leaps into his arms, his mother holds up a plastic bag with the first strike-out ball, and his friends laugh at the fact he’s carrying extra baggage onto the team readiest for the airport and a road trip. “A rookie thing,” Kershaw explains. “Gotta carry water onto the bus.”

The intro to the scene also shows Kershaw in full screen overwhelmed by the pre-game experience, sitting by his locker, mouth agape. A number 54 jersey hangs in his stall.

He would go six innings, give up two runs, and strike out seven. He had a 32-pitch first inning and logged 102 for his outing as the Dodgers eventually won the game, 4-3, in 10 innings. It’s also mind-numbing to see the horrid Dodgers’ starting infield for this one: Aside from James Loney at first, there’s someone named Luis Maza at second, Chin lung-Hu at short and Blake DeWitt at third, and a guy named Terry Tiffee later came up to get a pinch-hit single later in the game — his only hit in six games as a Dodger. Mark Sweeney, wearing No. 22, struck out in that game as a pinch hitter and then gave his number to Kersshaw, who grew up idolizing Giant-turned-Ranger All Star Will Clark.

Kershaw’s 5-5 record and 4.26 ERA in 22 starts in ’08, interrupted by a couple of trips down to the minors to overcorrect some roster moves, now feels like a lifetime ago. But there’s an emotional connection that allows fans to today say: I remember when …

And these days, as Kershaw fidget spins on the 60-day IL with a surgically repaired shoulder, hoping to return in July or August, he will put on the headset and talk to the team broadcasters during a telecast, staying loose and conversational. It’s part of the personality transformation of a three-time Cy Young winner, 10-time NL All Star and an NL MVP who already has the Dodgers’ career leadership in strikeouts and just 66 away from 3,000.

He could call it a day and retire to his home outside of Dallas with his wife and four kids. But he persists.

A career regular-season mark of 210-92, punctuated by marks of 21-5 (just two years after the doc’s release, in ’11), 21-3 (’14), 18-4 (’17) and 16-5 (’19), plus a combined 25-8 in his last two seasons (’22 and ’23) is often misaligned with a 13-13 mark with a 4.49 era in 32 starts during the post season. He is 3-6 in seven NL Championship Series.

His supposedly redemptive moment was the wonky 2020 playoffs — it started with throwing eight innings of three-hit shutout ball against Milwaukee in the wild-card clincher that included waving off the bench when it looked like he was going to be taken out in the pandemic-empty park. Then winning Game 2 of the NLDS against San Diego with six effective innings at Globe Life Field in Texas, but then coming back on eight days rest to lose Game 4 of the NLCS against Atlanta (5 IP, 4 ER). In the World Series, Kershaw registered wins in Games 1 and 5, staying at Globe Life Field — twice outdueling Tampa Bay’s Tyler Glasnow with 6 IP, 2 H, 1 ER and 8 Ks in the opener, and five days later, going 5 2/3 IP, 5 H, 2 ER and 6Ks, both times facing 21 batters. Julio Urias was essentially the pitcher who pulled the Dodgers out of any troubled times en route to that COVID title.

The last time we saw Kershaw in playoff mode was Oct. 7, 2023 in NLDS Game 1 at Dodger Stadium against Arizona, when he gave up six hits with eight batters faced and six earned runs in one-third an inning. His ERA was 162.0 for that series. The top-seeded Dodgers were swept away, scoring two runs each game and giving up 19 total.

Kershaw is hoping to write a different ending. A book like this helps direct that narrative — or at least explain what’s happened so far.

Not that he’s carrying the water this time, but McCullough, the former Los Angeles Times’ Dodgers beat writer who now covers the team for The Athletic, is among the few qualified to create a document of this nature at this tipping point in Kershaw’s professional existence. It comes at a pause before the baseball world may see his final act in the 2024 regular season leading into another toss-up postseason.

While Kershaw’s Hall of Fame plaque is pretty well set, even if he never puts on a pair of spikes again, the questions remain in the author’s pursuit of a story: Is Kershaw reinventing himself again in a game that keeps changing on him, or will he fight to the end? Is he ever satisfied with this blessing/curse of a starting pitcher’s existence in the 21st Century, working around pain, discomfort, stress and front-office meddling? A series of personal interviews that haven’t been published yet shed so much light on this.

Kershaw’s challenge is convincing Dodgers’ fans he’s still worthy of their adulation. This provides an emotional support manuscript.

But the game is changing, and his changeup may be his only out pitch left for the Last Great Starting Pitcher who won’t go gently into this night game that they’re trying to speed up.

(See: The Athletic/NYT, with stories today about whether the MLB can save the starting pitcher, what guys like Verlander and Scherzer say about it (too bad Rosenthal and Stark they didn’t ask Kershaw), and 12 rule changes that may bring the marquee starting names back into the spotlight — we like “Friday Night Is Ace Night” idea.

From his Highland Park home in Texas, to Studio City in L.A., Kershaw is old-school mashup with listening to those trying to help him stay around to fulfill his agenda.

It’s trying to remind him he’s not like his brother in arms, like Sandy Koufax, who went every fourth day, and even now, he’s not doing the every fifth-day thing any more. As McCullough says in the intro, Kershaw in his pre-fatherhood days was one with “outdated flip-down sunglasses … played cards on the team plane and unleashed righteous flatulence.”

He’s grown up. He loves Hollywood-obsessed ping pong and his part in that. From the buzz cut to the long wild hair and beard. Now he’s all sorts of things — but as he said, he’s not there to teach the game to younger pitchers on the Dodgers staff. Not yet, anyway. He’s there to keep competing, loyal to a franchise who helped create his one-team legacy despite temptations to jump to the Texas Rangers, with one of his good friends, Chris Young, as the GM of the current World Series champs.

With that, here are 22 things (it could be 54) we think we learned, or re-remembered, from reading through this:

22: While in the minor leagues in February, 2007, Kershaw once rolled his “dream car,” a black Ford F-150 King Ranch truck with leather interior, as he was driving overnight to see his then-girlfriend Ellen at Texas A&M. The truck flipped twice. Kershaw emerged with a single scratch, then called Logan White, the Dodgers’ farm director, to explain what happened.

21: Remember when Vin Scully blurted out — “Ohhh, what a curveball! Holy mackerel! He just broke off Public Enemy No. 1” — during a Dodgers’ March 9, 2008 spring training game against the Boston at Holman Stadium on a Sunday afternoon televised back to L.A.? It was against the Red Sox’s up-and-coming first baseman Sean Casey.

20: During Kershaw’s 2014 no-hitter at Dodger Stadium against Colorado, Charlie Culberson made the second out of the ninth inning with a fly ball to right field. “If you watch the tape, it’s the only two-handed catch of Yasiel Puig’s career,” said catcher A.J. Ellis.

19: Ellis explains “Playoff Clayton” this way in Chapter 14: “I don’t know how much Clayton will like this. My theory … I’m hesitant to even share it. I’ve never been around somebody who could get themselves to the maximum level on a Wednesday getaway day in Cincinnati at 12:10 p.m. When there’s 1,800 people in the stands, we’re trying to wake up as a team. But he would still max out. And he did it 34 times a year. He’s always here,” he says as he raised his right hand above his head. “He’s always here.” Then he raised his left hand to the same level. “In the playoffs, everyone gets here. And I think he got the sense of it. And so he would try to go (higher) and there was nowhere to go.”

18: Kershaw’s five-day cycle ritual, as explained on pages 173-174: “On the day after his start, he lifted, ran and played catch. On the second day, he threw his 34 pitch bullpen session. On the third day, he lifted and played long toss. On the fourth day, he climbed the bullpen mound for the visualization techniques he had cribbed from Derek Lowe. And on the fifth day, he muscled down his turkey sandwich and tossed the baseball against clubhouse walls, then took the field and dominated.”

17: Kershaw vowed to get to the big leagues before his 21st birthday. He beat that by 298 days.

16: McCullough dutifully describes Kershaw winding up to pitch in his first big-league game: “His legs and hands rose in concert. Up. Down. Break. One. Two. Three.”

15: Enjoyed all we could about Mike Borzello, “Zelig in a chest protector,” who was the first to properly assess Kershaw’s slider.

14: Enjoyed finding out about Dave Preziosi, who played with Kershaw for one summer in the Gulf Coast League. “You signed for $2.3 million, and I didn’t sign for anything,” Preziosi tells him, “and I have a better ERA than you.”

13: Far too many reference to Molly Knight’s 2015 tripe “The Best Team Money Can Buy” (maybe one is OK, two is too many) and not enough references to Pedro Mora’s 2022 book, “How to Beat a Broken Game: The Rise of the Dodgers In A League on the Brink.” Here’s more assessing the value of the later.

12: Kershaw aligned himself with Sketchers after Under Armor stopped making his cleats in 2018. He was never aware that the brand was not considered hip. “They’re super generous with Kershaw’s Challenge,” he says. McCullough adds: “That was how he became the face of septuagenarian footwear.”

11: Kershaw is “just a curmudgeon about certain things,” says his sister in law, Ann Higginbottom, who also runs his charity. “It’s almost like helping a toddler get dressed.” Page 337. Later, McCullough describes Kershaw’s “affable grumpiness.” Page 344

10: After Kershaw’s implosion against Arizona in the ’23 NLDS, he approached his wife. “I’m done,” he told her. Ellen adds: “He was at the height of emotions. I mean, this is exactly what insanity is: You keep doing it expecting different results, and ‘How am I back here?'”

9: If you need a real list of his real best baseball friends: A.J. Ellis, Brett Anderson, Brandon McCarthy, Zack Greinke, Rich Hill, Jamey Wright, Josh Lindblom, Joc Pederson, Justin Turner, Corey Seager, Tyler Anderson, Kenley Jansen, and, as a coach, Rick Honecutt.

8: Kershaw is always weary of what manager Dave Roberts may say about him.

7: Flash back to Kershaw’s first start of the 2022 season: Seven perfect innings pitched at Minnesota.

In the press, Kershaw said he agreed with Roberts’ decision to take him out — as Roberts did with other pitchers in recent history. Kershaw had a short springing training because of the labor issues. It was 38 degrees at Target Field. Ellis later yelled at him for not trying to stay in the game.

“I probably regret it now,” Kershaw says in the book to McCullough. “I think throwing a perfect game would have been cool. Doc, he wanted to take me out. Mark (Prior, the pitching coach) wanted to take me out so bad. I could really do what I usually do and make it super hard for them and stress them out. Or I just take it. So I just took this one. Looking back, I regret it. I should have at least tried.”

6: The whole Pride Night fiasco of 2023, when Kershaw asked the team to reactivate Christian Faith and Family Day: “The Dodgers really put us in a horrible position,” Kershaw told McCullough. “It’s not an LGBT issue. It’s just, like, that group (the Sisters of Perpetual Sorrows) is pretty rough. And I’m all for funny and satire, but that goes way beyond it. So I did feel I needed to stay something.”

5: From October, 2023: “I’ll get a little honest with you — Faith-wise, the last year has been harder for me … You’re supposed to feel the presence of the Holy Spirit when you pray. And my prayer life sucks. I can’t pray well. I have a tough time voicing how I feel.” Page 339.

4: The first of his four kids, Cali, was born just before he was to receive his first Cy Young Award at a New York ceremony. Was given that name to reflect the Texas family’s new homestead in California? It’s no where in the book that we could find, so we went to look it up. From a 2015 Father’s Day story on ESPN.com, Kershaw says: “Cali was a name I’ve always loved. My teammate Brandon League has a daughter named Callie, and she’s the cutest thing ever. So that might’ve helped. Ellen said, ‘OK, you can name her. But I get to name the next one.’ Ann is a family name; Ellen’s grandmother and sister are both Ann.”

3: After the Dodgers won the 2020 World Series, Kershaw “blasted Queen’s ‘We Are the Champions’ loud enough that his neighbors could hear it when they strolled by, often enough that his kids grew sick of the song.” It says on page 323.

2: Interesting to find out author McCullough’s wife is Stephanie Apstein, who he proclaims “wrote the best story about Clayton Kershaw” for Sports Illustrated in 2018 called “The Control Pitcher: As Free Agency Looms, Will Clayton Kershaw Win It All in L.A.?” Apstein is also referenced in our recent review of the new Sports Illustrated Baseball Vault issue.

1: There were 215 people interviewed by McCullough for this book. Including Sandy Koufax. And a lot of Kershaw. Which is most important.

How it goes in the scorebook

As complete a game as one can record these days. More that just a quality start to a story that will be updated once the retirement papers are signed and life begins as a full-time dad. Kershaw seems to feel a burden has been lifted, and now he’s able to share, in the newspaper, and in this book. It’s worth everyone’s attention.

In total, the book provides clever clues and contemplative conversations that fill gaps. It has nuance and context that bridge straight reporting of the past.

Also, the cover shot taken by Abbie Parr for Getty Images is also so dazzling, we couldn’t help but blow it up bigger than usual for these reviews. Signed poster, anyone?

You can look it up: More to ponder

It will easy to track down all sorts of reviews and media done on this book. That’s built-in for this type of tome on a current, popular athlete.

From TrueBlueLA to all other shades of azure.

McCullough is also able to offer up excepts in The Atlantic and the L.A. Times.

More examples:

Also: Is this anything?

== In Joe Posnanski’s current list of the 50 most famous baseball players in the last 50 years — going back to 1974 — he has slotted Kershaw at No. 43. And in a poll Posnanski took among his readers had Kershaw at No. 30.

Posnanski, author of the famously popular “Why We Love Baseball: A History in 50 Moments” in 2023, which came after “The Baseball 100” in 2021 (which really measures greatness instead of fame, and Posnanski has Kershaw at No. 78 in his book, ahead of Derek Jeter and after Miguel Cabrera) writes about Kershaw in a fantastic analysis (some borrowed from the “100” book) that seems to have overlooked this McCullough book release (since this will help very much to KNOW Kershaw):

“He obviously won’t get to 300 (wins) now. He won’t get close. So if he won’t get to 300, why bring it up in a story about Kershaw’s fame? Because I wonder: With pitcher wins becoming an afterthought — and 20-win seasons and 300-win careers going extinct — can pitchers be famous in the years ahead? Kershaw’s fame is of a particular kind … I’d call it an old-fashioned fame. He has deliberately avoided the spotlight. I mean: What do you KNOW about Clayton Kershaw? … His fame revolves entirely around his pitching brilliance. That feels to me like a very 1950s kind of thing. … Kershaw’s time is history. … I guess we are required by law to discuss Kershaw’s struggles in October. They, too, alas, are part of his fame. … In any case, it’s all in the books now. The age-20s Clayton Kershaw was so great that Vin Scully would sometimes find himself calling him Koufax. The post-30 Kershaw has been great, but often injured. The postseason Kershaw has had his triumphs, but has also been a mystery. It’s been quite a career.”

== Posnanski also dug up this interesting piece of data:

Kershaw’s favorite ump: Cory Blaser (3-0, 0.58 ERA)

Kershaw’s least-favorite ump: Bob Davidson (1-2, 6.65 ERA)

Kershaw won more games with Greg Gibson calling balls and strikes (7-0), and had a lower ERA with John Hirschbeck (4-0, 0.32), but with Blaser behind the plate, Kershaw struck out 31 batters in 31 innings and walked… one. As for the other side, Kersh had one bad experience with Ed Montague, where he gave up six runs in 4 1/3 innings, but he found it consistently tough with Davidson.

== And if you’ve still got a beef with Kershaw after all this …

The ’24 Baseball Bio lineup: Even more to ponder

What’s the “state of the baseball biography in 2024?”

Charlie Beavis, a baseball historian who thinks about these things, posted recently: “Baseball impact is now largely foundational content in a baseball-related biography. There is no need to consume extensive space with details to prove a person was highly successful in baseball. That will be obvious to most readers by the title before they even open the book. The person’s baseball impact would also best be framed within specific themes (particularly if related to a change in the game itself), rather than merely games and seasonal statistics, with threads that can be woven throughout the book’s text. What’s more important to a quality biography is the person’s impact within a relevant cultural issue and the author’s assessment of the person’s character. Many of the better recently released biographies of ballplayers are updates to previously published works. This may be a more fruitful approach for future biographies than tilling new ground on a first book about a lesser-known player with minor cultural impact and unremarkable character.”

One of the best coming out will be “The Original Louisville Slugger: The Life and Times of Forgotten Baseball Legend Pete Browning,” by Tim Newby, which Beavis calls “one of the best biographies of a 19th century ballplayer ever written.” For our purposes, we haven’t seen a review copy, and it’s not scheduled for release until this fall.

So, in addition to reviews we’ve done in ’24 on baseball player books by/about Waite Hoyt, Mike Donlin and another (yawn) look at Pete Rose, we will use this post as a roundup of all the others we’ve come across, wanted to do a deeper dive, but have run out of bandwidth — also noting an odd similarity in the lack of imagination on how they are titled:

== “Tony Gwynn: The Baseball Life of Mr. Padre,” by Scott Kingdon (McFarland, 204 pages, $29.95, release October 16, 2023):

Twenty seasons in San Diego — eight batting titles, including .370 in 1987, 15-time All Star, five Gold Gloves, seven Silver Sluggers, 3,141 hits and a .338 lifetime average in more than 10,000 plate appearances. Tony Gwynn, born in L.A. and growing up in Long Beach to take advantage of the plentiful ballfields near Silverado Park, finally gets a complete bio treatment here that’s long overdue, by someone in Indiana who once got to see him play there in a Padres exhibition game. “I began this project believing Tony’s life offers a message worth savoring,” Kingdon writes. “Nothing I discovered changed my mind.” Maybe his lasting impact: The Major League Collective Bargaining Agreement was amended in 2016 to bar the use of smokeless at games or team functions by players who entered the major leagues.

== “Big Cat: The Life of Baseball Hall of Famer Johnny Mize,” by Jerry Grillo (University of Nebraska Press, 304 pages, $34.95, released April 1, 2024).

Meow. Long before Tony Goslin made cats somewhat cool, this cool cat Johnny Mize put of Cooperstown-quality numbers, but couldn’t claw his way in until the Veterans Committee stamped his passport in 1981, eight years after his 14-year ballot search expired in ’73 (and topped out at just 43.6 percent of the vote in ’71). A 10-time All Star, a .312 career batting average (a batting champ with .394 for St. Louis in ’39), four-time NL home run leader with 359 total in 15 seasons, and three time NL RBI champ — despite missing 1943 to ’45 for military service. He hit for power and average like Albert Pujols, a line-drive hitter who rarely struck out. This is the first real bio on him.

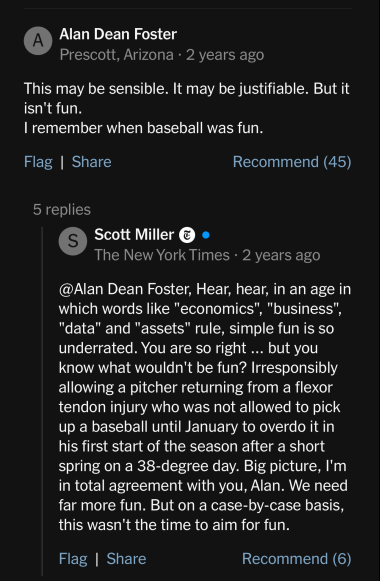

== “Roberto Alomar: The Complicated Life and Legacy of a Baseball Hall of Famer,” by David Ostrowsky (Rowman & Littlefield, 276 pages, $36, released Feb. 6, 2024):

Complicated? How so? Oh, right. The spitting things. And more allegations. Roberto Alomar came from a baseball family: His father Sandy played for the Angels. His brother Sandy Jr. played for the Dodgers. Roberto, who retired in 2005 after 17 seasons with San Diego, Toronto, Baltimore, Cleveland, the New York Mets, Chicago White Sox and Arizona — none of them more than five seasons — was inducted into Cooperstown in 2011 on his second try with a career .300 average, 210 home runs (16th all time by a second baseman), a 12-time All Star and 10-time Gold Glove winner.

== “Dewey: Behind the Gold Glove,” by Dwight Evans with Erik Sherman (Triumph Books, 256 pages, $30, to be released July 16, 2024).

The legend of Dewey Evans is a bit different than the legend of Dewey Cox, but we couldn’t help but try to make a connection there. Dwight Evans in his Tom Selleck sort of personna did more than walk hard, throw hard and run hard out of Chatsworth High in the San Fernando Valley. He played hard, and had the Glove Gloves to prove it. But there’s more? During the 1980s, it should be noted that no one had more extra base hits in all of baseball, and no one had more homers in the American League. Yet in three Baseball Hall of Fame ballots, he was no longer in the consideration after 1999. Eight Gold Gloves, five times in the AL MVP voting balloting, three-time AL All Star, he’s right there statistically in the Carlos Beltran/Luis Gonzalez/Darrell Evans/Andrew McCutcheon/Reggie Smith company. Twice led the AL in OPS (when it wasn’t really a thing), three times leading the AL in walks, twice scoring 120-plus runs a season, and the AL leader with 22 homers in the strike-interrupted 1981 season. We need no more convincing, and we’re convinced this book is overdue — much like the Ron Cey book of 2021.

== “A Baseball Gaijin: Chasing a Dream to Japan and Back,” by Aaron Fischman (Sports Publishing, 424 pages, $25.95, to be released June 18, 2024):

Tony Barnette was an Arizona Diamondback draft pick out of Arizona State in 2006, but couldn’t make it quite to the big leagues. He does have an MLB data base career: Four seasons, with the Rangers and Cubs, 11-4 record in 127 relief appearances, from 2016 to 2019, finished at age 35. In between, that’s the story. By 2009, he was 14-8 in Triple A Reno for the D-backs (leading the PCL in wins), but with a 5.28 ERA. For six seasons, from 2010 to ’15, he was a Yakult Swallow, going 14-22 in in 282 games, finishing 159 with 97 saves. Didn’t know Japanese, the culture, or the landscape, just that he would get a fighting chance. A Gaijin (Japanese for “foreigner”) has been successful before in the Nippon Professional Baseball league. Here’s another story about that journey.

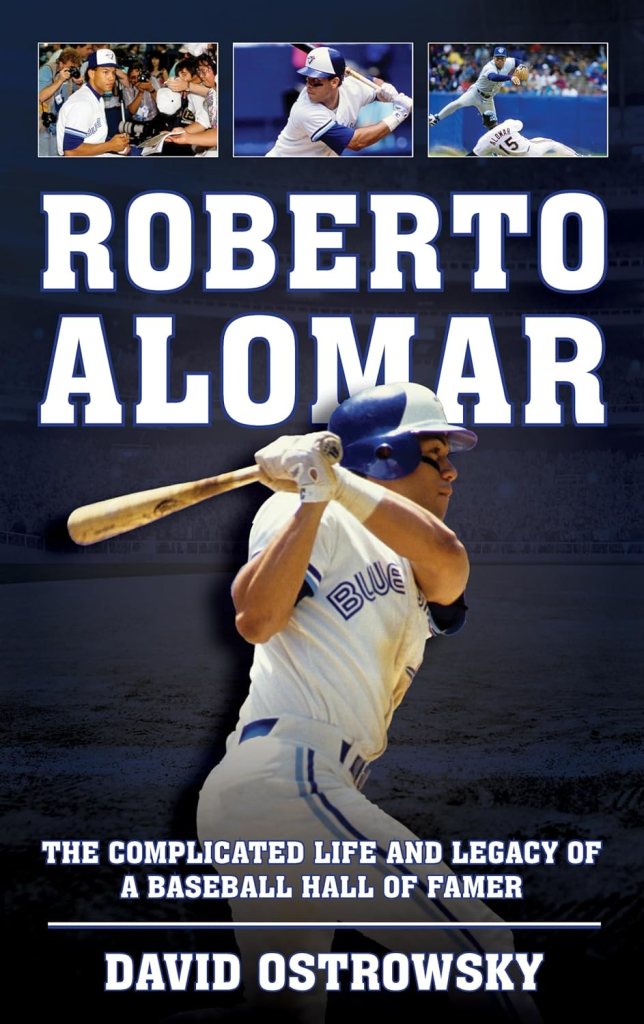

== “Hoyt Wilhelm: Life of a Knuckleballer,” by Lew Friedman (McFarland, 218 pages, $35, released Feb. 18, 2024).

Knuckling it up for more than 1,000 games — 52 starts, 20 complete games, and 651 finished for 228 saves in more than 2,200 innings — Hoyt Wilhelm once led both leagues in ERA (2.43 as a 29-year-old New York Giants rookie in 1952; 2.19 as a 36-year-old Baltimore Orioles All-Star in ’59). He spent his last two seasons with the Dodgers in ’71 and ’72, retiring at age 49. He also spent part of a season with the California Angels in ’69.

“Parisian Bob Caruthers: Baseball’s First Two-Way Star,” by David Heller (McFarland, 232 pages, $39.95, released Feb. 18, 2024).

Robert Lee Caruthers was a 40-game winner as a 21-year-old for the St. Louis Browns of the American Association in 1885, also winning the ERA title at 2.17, and won 40 more with the Brooklyn Bridegrooms in the National League in 1889. He somehow posted 218 wins in just nine seasons, then discontinued the throwing part in 1892. As a right fielder/hitter from 1885 to 1893, he had a .282 career batting average and retired as the game’s leader in stolen bases with 152, with a high of 49 in ’87. Coming from a wealthy family, Caruthers had leverage when it came to contracts, so he could hold out, even play in Europe. A fascinating profile.

== “Roger Bresnahan: A Baseball Life,” by John R. Husman (forward by John Thorn, McFarland, $39.95, 291 pages, released May 8, 2024):

The first bio done about Roger Bresnahan, who started as an 18 year old with the 1897 Washington Senators of the National League and spent seven strong seasons with the New York Giants (1903 to 1908) as a .279 career hitter. His pitching: The 1987 with Washington, going 4-0 with a 3.95 ERA in six games. He finished his career as a catcher, introducing shin guards to the game. Here’s a true utility player — including coaching and managing. He was later principal owner and president of the Toledo American Association franchise for eight years.

== “The Wright Side of History: The Life and Career of Johnny Wright, Co-Pioneer in Breaking Baseball’s Color Barrier, As Told by his Daughter,” by Carlis Wright Robinson with Fredrick C. Bush (In Due Season Publishing, $19.99, 189 pages, released in December, 2023).

The live and times of a one-time Brooklyn Dodgers minor league pitcher known as “Needle Nose” more famous for his days in the Negro Leagues with the Newark Eagles, Toledo Crawfords and Homestead Grays, and on the 1943 Negro League champions, is conveyed in a book targeting young adult readers. Wright was with the 1946 Montreal Royals Triple-A team with Jackie Robinson by orders of Branch Rickey. Was Wright there to be a companion on Robinson’s journey or could he have been the one picked to break the color barrier? Wright only lasted a couple of games in Montreal and was demoted to Class-C, and another Black pitcher, Roy Partlow, was brought up to Montreal. As Wright’s daughter explains: “My Dad was moved to the background so that the main character in his story, Jackie Robinson, would have all of the focus and the headlines. I understand that and am not trying to downplay what Mr. Robinson accomplished in any way. However, it is now time for Johnny Wright to have his full story told.”

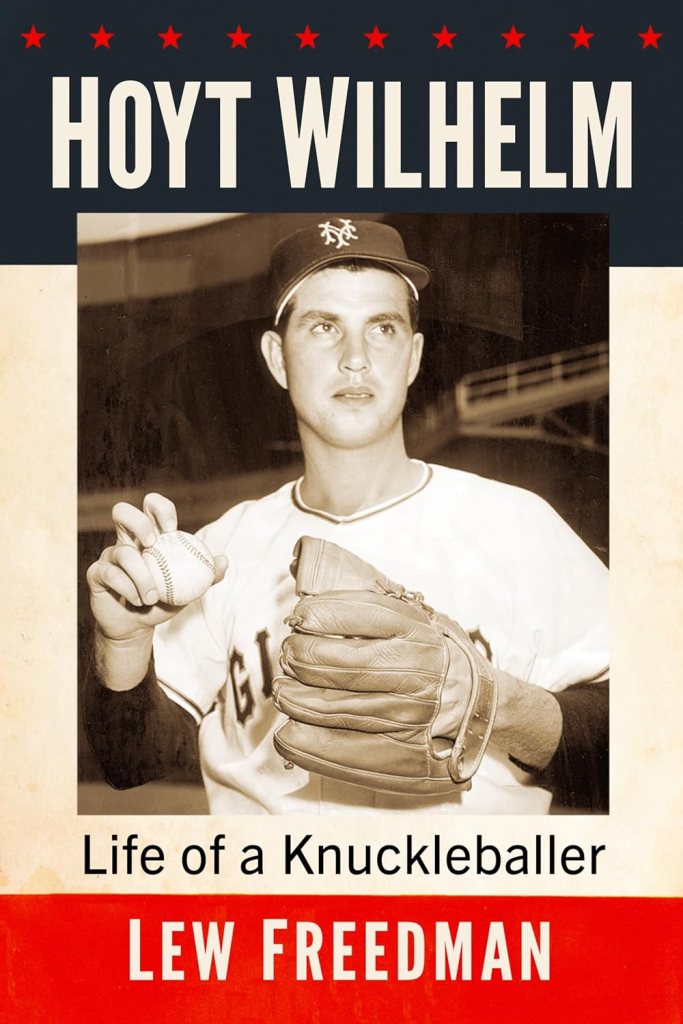

== “Cookie Rojas: A Baseball Life,” by Lou Hernandez (McFarland, 216 pages, $29.95, due for release June 16, 2024).

Gotta dig the clear-framed large glasses worn by Octavio “Cookie” Rojas, who put in a 16-year career mostly split between the Phillies and Royals, and then managed the California Angels in 1988 during his a 50-year career in the game that included time as a coach, scout and broadcaster. The Cuban native left his country following the revolution and just wanted to play baseball.

But to us it also begs the question: Is this a photo illustration of him from the All Star Baseball Game with the spinner we used to play almost daily as a kid?

2 thoughts on “Day 28 of 2024 baseball books: Kershaw’s challenge is to tell his lasting ‘baseball life’ story in a kind way”