This is the latest post for an ongoing media project — SoCal Sports History 101: The Prime Numbers from 00 to 99 that Uniformly, Uniquely and Unapologetically Reveal The Narrative of Our Region’s Athletic Heritage. Pick a number and highlight an athlete — person, place or thing — most obviously connected to it by fame and fortune, someone who isn’t so obvious, and then take a deeper dive into the most interesting story tied to it. It’s a combination of star power, achievement, longevity, notoriety, and, above all, what makes that athlete so Southern California. Quirkiness and notoriety factor in. And it should open itself to more discussion and debate — which is what sports is best at doing.

The most obvious choices for No. 3:

= Carson Palmer: USC football

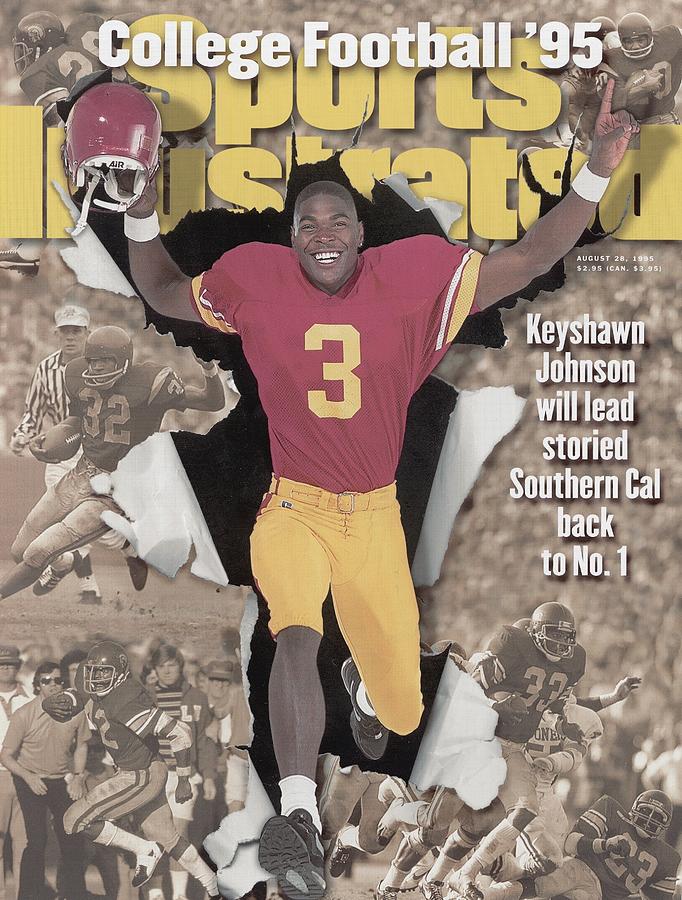

= Keyshawn Johnson: USC football

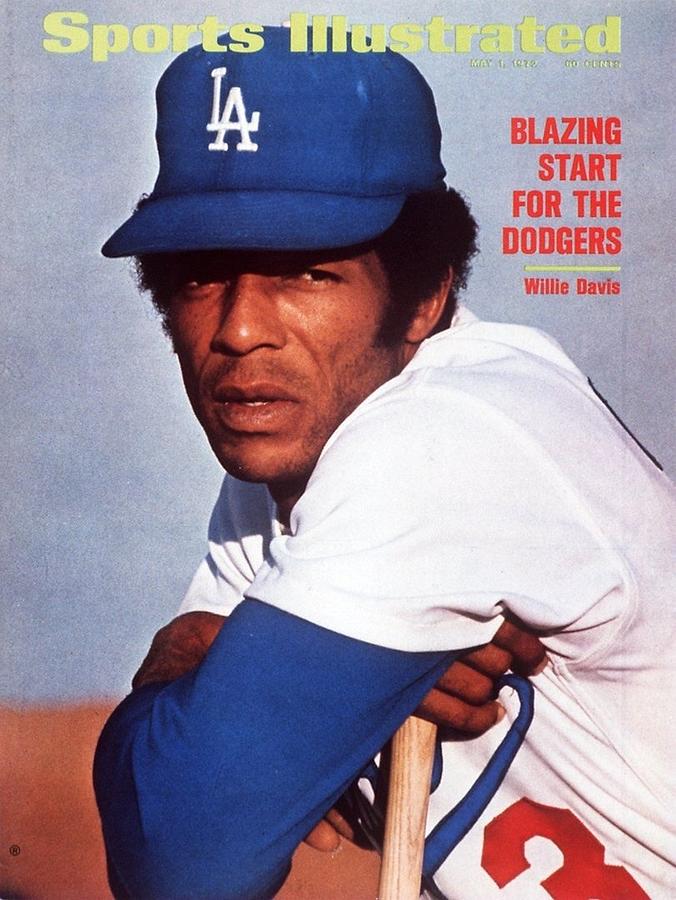

= Willie Davis: Los Angeles Dodgers

= Anthony Davis: Los Angeles Lakers

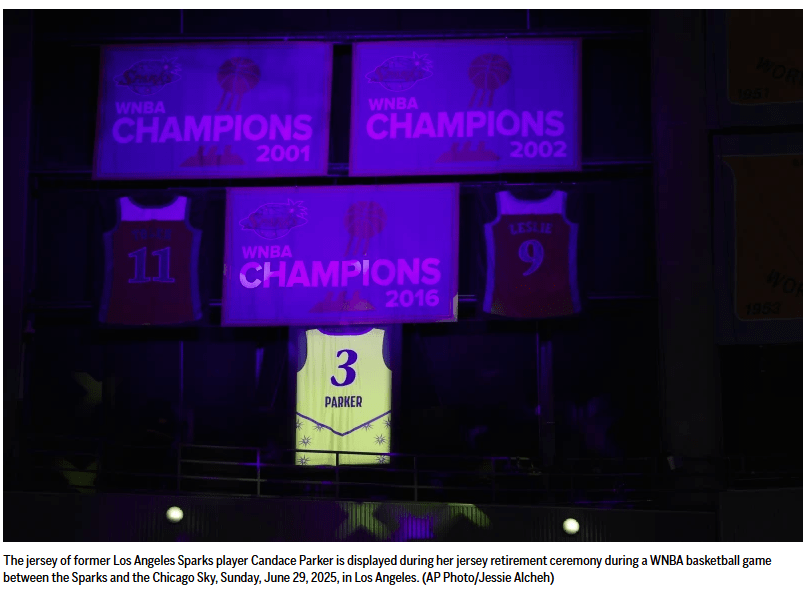

= Candace Parker: Los Angeles Sparks

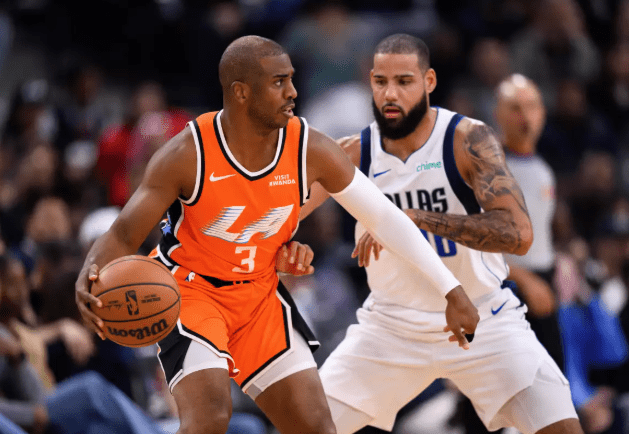

= Chris Paul: Los Angeles Clippers

The not-so-obvious choices for No. 3:

= Josh Rosen: UCLA football

= Glenn Burke: Los Angeles Dodgers

= Steve Sax: Los Angeles Dodgers

The most interesting story for No. 3:

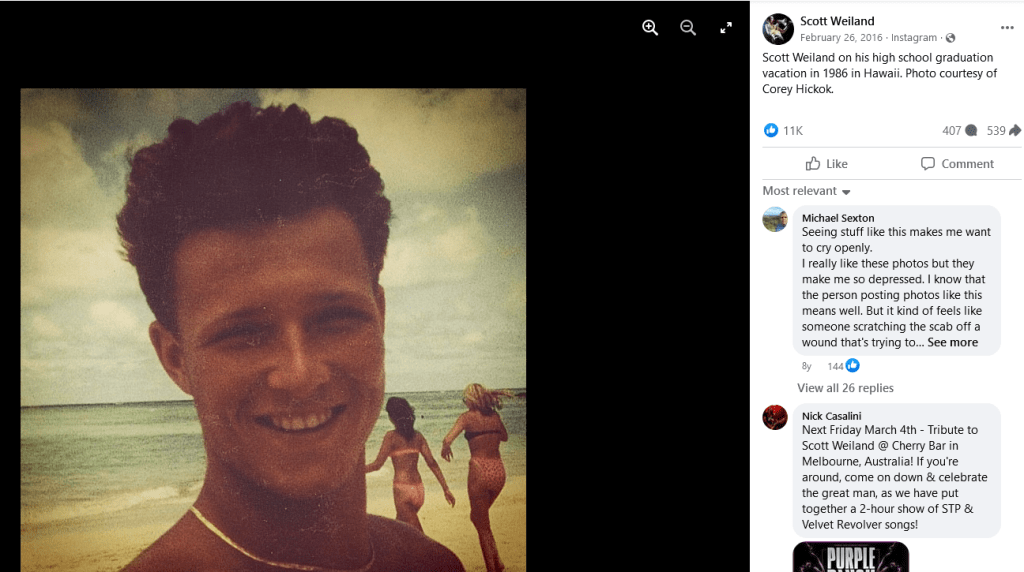

Scott Weiland: Edison High of Huntington Beach football quarterback (1982 to 1985)

Southern California map pinpoints:

Huntington Beach, Costa Mesa, Long Beach, Hollywood

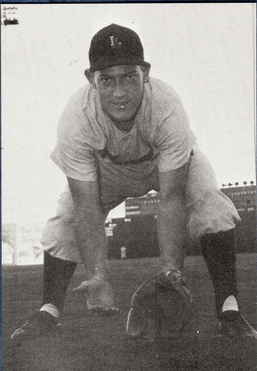

The photo documents perhaps the only tangle circulated evidence that Scott Weiland played football — an aspiring quarterback trying to make his mark at Edison High School in Huntington Beach.

He kind of looked like a young Sean Salisbury — ready, willing and able to commandeer a team to success and fame. The hairstyle of the moment was helmet friendly.

Yet, the eventual lead voice and flamboyantly driving force in and out of Stone Temple Pilots, Velvet Revolver and Art of Anarchy, fired or otherwise bored with each venture, wouldn’t be on track to become the famous college football player as he once thought he’d like to be.

High school non-confidential: The teen years focused on self discovery, watching, listening, hatching experiments, hormones raging, expectations and lack of sleep leads to falling into groups of new fast friends and/or swallowed up by cliche cliques.

At a peak of his music fame in 2007, Weiland was asked in fan Q&A about his high school activities.

“What kind of self-respecting outcast were you?” he was asked.

He explained:

“One with a lot of cojones. I was never a jock, but I was an athlete, and I was good. (Edison High) had just won multiple state football titles; it was a hardcore football school. I had aspirations of going to Notre Dame, so I played quarterback. But also I was into music: I sang in the school choir; and the two worlds didn’t really hold hands skipping down the hallways. I got a lot of flak from the coach and the guys on the team. Then I formed a rock & roll band with my best friend, and at the start of the senior year, I decided that I was into music more.”

While there is the one football photo, there thousands more snapshots, videos and websites that celebrate Weiland’s legendary music work — nominated for six Grammys, winning two for Best Hard Rock Performance, selling 50 millions records and called a “voice of our generation” by Smashing Pumpkins’ Billy Corrigan.

Some critics might have thought his bands were “a shameless clone of such grunge leaders as Pearl Jam, Nirvana and Soundgarden.” But taken individually, Weiland was called “one of the towering figures in the history of rock” by Rolling Stone magazine.

Audiences and fans were captivated by a chaotic stage presence. He was a champion chameleon, amplified by a megaphone. All in all, he navigated the diversity of glam, and alt rock, and pop, and hair-metal ballads far better than he did toxic mix of drugs, alcohol and all else the came to consume him.

So when he died in 2015 of a drug overdose at the age 48, the question had to be asked: How will he be remembered?

We are left with shards of facts and quotes and guesses. And photos. Many provided by him.

The background

In his compelling and complex 2011 memoir, “Not Dead & Not For Sale,” marketed as “an exhilarating (work) scaling the pinnacle of rock stardom, plunging into the chasm of addiction and incarceration, and then clawing his way back to the top again and again,” the football photo of Weiland above is included on page 22. There’s also a photo of him wrestling.

The caption for the two photos reads: “What everyone wanted for me.”

Scott Richard Kline was born on Oct. 27, 1967 in San Jose. His parents divorced when he was two. By age 5, his name was legally changed to reflect his adopted step-father’s surname, Weiland.

Readers of his story find out quickly toxic he was dealing with “Dad Kent” and “Dad Dave.”

As Weiland wrote about growing up in Chagrin Falls, Ohio, just outside of Cleveland: “My childhood was green pastures and bee stings, learning to play baseball and football, living in a nice house, waiting — always waiting — for the start of summer so I could go to California and see my dad Kent.”

It wasn’t an easy shared experience to give him a healthy outlook on life.

“I lost my name. I lost my father. I gained another father. Later, I resented the hell out of my blood father, Kent, for not insisting that I keep his name. I felt abandoned … Kent’s the father I wanted to be with.”

Dad Kent was a truck driver. Stepfather Dave, at 6-foot-5 and 240 pounds, introduced him to sports. Particularly Notre Dame football — his alma mater. Scott was also starting a life raised Catholic, so the Notre Dame ethos can become ingrained on that journey.

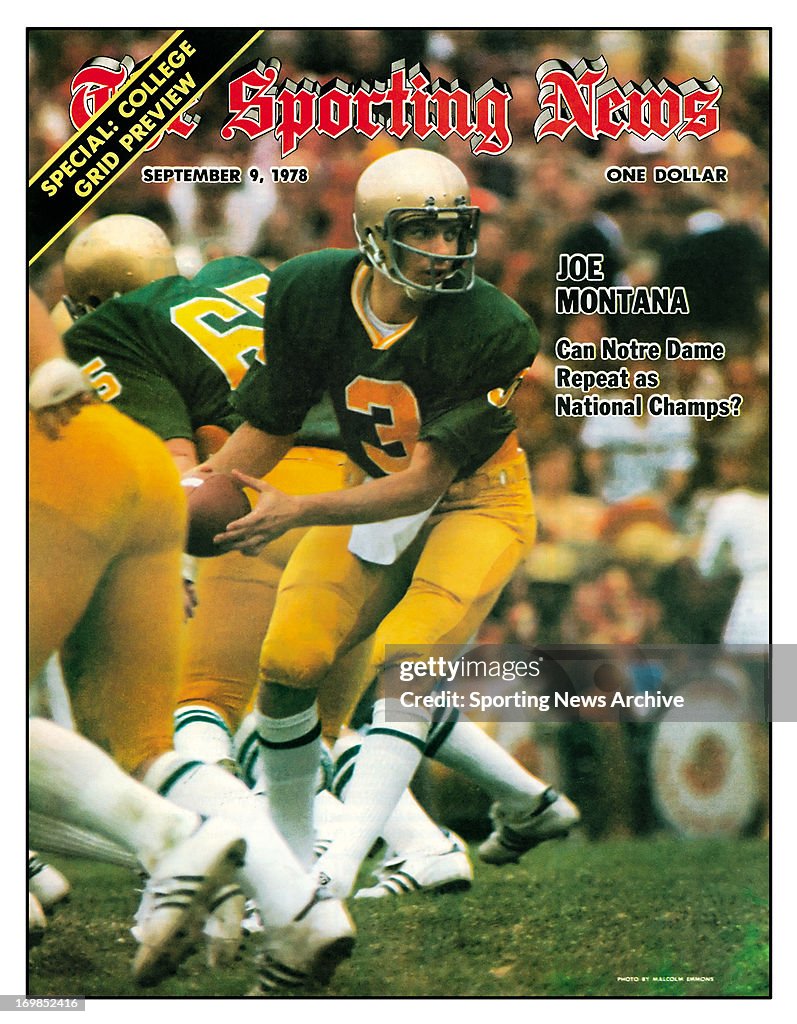

During his most impressionable years growing up, Weiland, for example, experienced the Fighting Irish winning national champions in 1973 and 1977. That second title team was quarterbacked by Joe Montana. Wearing No. 3. The blessed trinity.

Maybe there’s a connection?

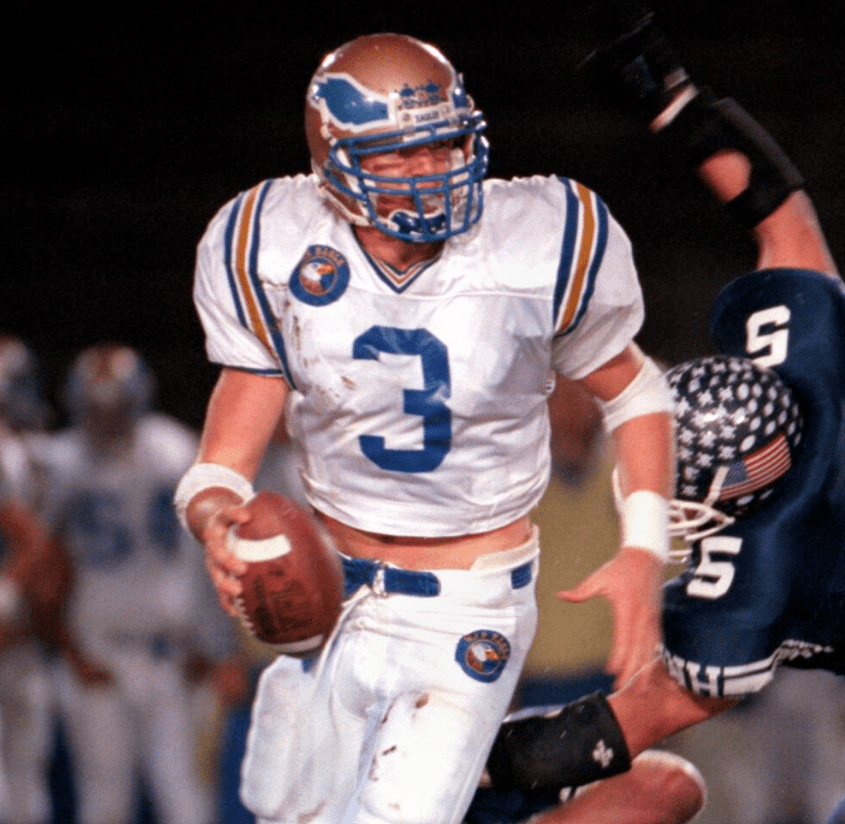

Weiland’s move to Surf City with his family unit and starting at Edison High as a 14-year-old freshman in 1982 was also a time when Steve Beuerlein was the senior quarterback at Servite High in Anaheim. Beuerlein led his team to the CIF Southern Section 5A title. The next year, he was starting as a freshman at Notre Dame and would break every passing and total offense record in Irish school history by the time he was finished in 1986.

So if there was some Orange County/Notre Dame quarterback path to success, Scott Weiland had a template. But he fought it.

“I had the hope that comes with being a kid with natural athletic ability,” Weiland writes in his memoir. “By the eighth grade I was able to launch a football fifty yards. The summer before my freshman year, I practiced with the team every day and achieved my goal: I was tapped as starting quarterback.

“I was haunted by a dream that, decades later, still recurs: I’m in the huddle, call the play, get the snap, drop back to pass, survey the field, and see, thirty yards away, my wide receiver two steps ahead of his defender. I cock my arm and, just when I’m ready to launch a rocket, the football slips out of my hand for no reason. A lineman recovers the fumble and the game is lost.”

He still felt as if he was “the All-American Ohio boy with a far-off dream of playing for Notre Dame … I wanted the prestige and attention that came with being QB — not to mention the thrill that comes with being the field general. I thrived on competition.”

Just weeks before he was to play his first game as a high school freshman — “I smelled triumph; I longed for glory,” he wrote — “Dad Dave” moved him, his mom and younger brother to Huntington Beach. Their new house was right across the street from Edison High.

“The first thing I did was hand a note to the football coach,” Weiland wrote. “It was a message from my old coach that said I was a starting QB. The new coach wasn’t overly impressed. I was five eleven and weighed 155 pounds. The Edison team had won several championships. I’d have to wait.”

Weiland explained that his football plans changed by his sophomore year, when he was rotating with other quarterbacks and also played defense. He said going for an interception, he was speared from behind and out with an injury for several weeks.

“I took that time to consider my options,” he said. “I could keep playing without much of a chance to start at QB because, I always thought, my parents weren’t doling out money to the boosters’ club, or I could try something else.

“Rock-and-roll, like a siren song, was calling to me.”

The pivot

Weiland’s first exposure to music in Ohio was with the Southern California legendary Beach Boys, along with The Beatles and Cheap Trick. After his move to Southern California, his influences expanded to include harder-edged groups–everything from the Clash to the Sex Pistols and Depeche Mode to Echo and the Bunnymen. He was sweet on Sweet. He picked on the OC punk-rock counterculture.

In 1985 — the same year that football photo was taken — Weiland and high school friend Corey Hickok connected. Because they had been connecting on the football field. Hickok played tight end.

“But more important, he played guitar in his big brother’s punk band, Awkward Positions,” Weiland wrote. “Cory turned me on to punk.”

They formed a band, Soi-Distant, a French phrase for “self style.”

Wieland tried his hand in several groups, influenced by Social Distortion, U2, the Cure. If football was about Xs and Os. Weiland was more into Ultravox.

Their Friday Night Lights were at clubs such as Cuckoo’s Nest or Deja Vu, making $200 a night “plus all the booze we could keep down.” This was the summer before his junior year.

Meeting bassist Robert DeLeo at a 1986 Black Flag concert in Long Beach led to Weiland pulling together a group called Mighty Joe Young. It would eventually take the name Stone Temple Pilots. It was the nostalgic fondness of the letters “STP.”

Ask any kid growing up in that area about the coolness of having an “STP” sticker on their bike, especially a free one they got from begging the local mechanic working on their dad’s car. It was the logo of winning race cars and motor bikes. Especially in that part of Orange County created by an oil drilling boom.

The Edison High sports teams nickname remains the Drillers.

This was also a school named after the fact the Southern California Edison Company donated much of the land the school was built on. During the 1970s, Edison High School served the second largest student population west of the Mississippi.

Kerwin Bell, a high powered running back and 1979 Cal-Hi Sports “Mr. Football,” may have put the school on the football map shortly after quarterback Rick Bashore drew attention in the mid ’70s, eventually becoming a starter at UCLA. By 1983, Edison High was ranked No. 1 in Orange County and went as high as ranked third in the nation by USA Today under coach Bill Workman. Edison’s quarterback in ’85 was Mike Angelovic, who Workman said “reminds me a lot of Rick Bashore with his running ability.”

The Edison legacy reached new heights in 2024 when Sam Thomson threw a 54-yard touchdown pass to Jake Minter with 20 seconds remaining and secure a 21-14 win over Central of Fresno in the CIF State Division 1-A championship at Saddleback College in Mission Viejo. The win gave Edison (12-4) the first state football championship in the program’s history.

In the 1985 Edison High yearbook, Weiland was captured as a popular, good looking kid who, in addition to playing football, enjoyed volleyball, wrestling, surfing, sang in both the Men’s Choir and the Accapella Choir, and he was a homecoming King of Courts nominee.

He went by the nickname “Wyner.“

Stone Temple Pilots became Weiland on vocals, Eric Kretz on drums and Robert DeLeo’s older brother, Dean, on guitar. It hammered that home though a strategy of starting at some Southern California night clubs and stadium venues but venturing out to find their audience. Weiland wrote the first major gigs for STP were at the Palladium and the Whiskey in Hollywood and the Shamrock in Silver Lake.

As Hickok recalled for OC Weekly: “I asked Scott if he would like to sing for a new band I was forming. Scott jumped at the opportunity. We immediately clicked and before long, Soi-Disant was playing in small clubs all over Orange County. … Once a week they would get a to play a full set of originals in between DJ music and started to create a rather impressive following. At 16 years-old, our band Soi-Disant was hiring tour busses to come to Edison High and bringing upwards of 200 kids to watch us play at The Roxy in Los Angeles. Within minutes of the busses pulling up in front of The Roxy the place was packed and Soi-Disant was playing to a sold out crowd.”

While Weiland would also go to Orange Coast College in Costa Mesa after high school, the rock scene secured his attention and became his identity, and he would experience 30 full years of it.

His voice reminded many early on of Pearl Jam’s Eddie Vedder, but Weiland evolved as the music changed and he was experimenting. In style and look and glam and everything else that was evolving.

“People make it sound like we suddenly appeared from nowhere, made a record and sold 4 million copies,” Weiland told the L.A. Times in 1994 during an interview in West Hollywood’s Sunset Marquis Hotel, where the band has gathered from home bases that stretch from San Diego to Topanga Canyon. “Part of the reason we seem new is we tried to distance ourself from the L.A. scene. The truth is we played small clubs and watched a lot of other bands get blown up and hyped out before ever doing anything.”

“I just thought he was a great singer,” said guitarist Slash in his own 2007 autobiography. “He was the one vocalist that I knew had the kind of voice that would serve what we were going to do: He had a John Lennon-ish quality, a little bit of Jim Morrison, and a touch of almost David Bowie. He was the best singer to come out in a long time in my opinion.”

Stone Temple Pilots’ 1992 album debut, “Core,” broke into the Top 10 and sold more than four million copies. Two years later, the album “Purple,” was just as big a hit driven by hits on the radio such as “Creep,” “Interstate Love Song” and “Vasoline.“

As success escalated, so did Weiland’s drug use.

“I associated heroin with romance, glamour, danger and rock-and-roll excess,” he wrote. “More than that, I was curious about the connection between heroin and creativity. I couldn’t imagine my life (as I was ) entering into the major leagues of alternative rock without at least dabbling with th eKing of Drugs. So I put in my order.”

Diagnosed as bipolar, his abuse and arrests from having and using crack cocaine and heroine was part of his journey as well. In and out of rehab and jail. Heavy drinking. Asked in the fan Q&A about what drugs he never tried, he said: “I’ve done just about everything at least once. There are a couple I’ve never done, and that’s just because I couldn’t find them.”

In 1998, he told the L.A. Times: “I feel lucky to be alive. Life doesn’t make any sense unless you can enjoy the journey, and sometimes I take that for granted. But I try not to do that now. I try to learn from my mistakes.”

Still he had a connection to Notre Dame football. Weiland even got mentioned in a 2007 edition of Sports Illustrated:

Velvet Revolver’s “Fall to Pieces’ sounds like a standard hard-rock love song, but when front man Scott Weiland sings it, Notre Dame’s 13-year bowl game losing streak is probably in the back of his mind. The former Stone Temple Pilots lead singer, whose father, David, is a Notre Dame alum, is a huge Irish fan and often blogs about the team on scottweiland.com. With rumors flying that coach Charlie Weis might flee South Bend for an NFL job, Weiland was moved last week to write, “Leaving Notre Dame without having achieved really anything of monolithic proportions like you promised us, is absurd and unfair. I will get on my knees and beg. Don’t do it, coach. Don’t do it! Stay and do what you promised.”

But being a team player in a band wasn’t always Weiland’s perfect fit.

“I’ve always been half out and half in,” he wrote about his group performances. “My nature is that of an individual artist. I can get excited about joining the team and going for the gold; I can even be a gung ho team player, but not for long. … My pattern is pretty clear.”

In March of 2015, Scott Weiland just released “Blaster,” his third solo effort on his own label consisting of original material.

“I haven’t been this excited since I made my very first album, which was ‘Core’ (Stone Temple Pilots 1992 debut),” he said at the time. “It’s like starting from the beginning again. There’s that anticipation and all of the work that goes into building something from the ground up so, right now, I am happy.”

On Dec. 3, less than nine months later, a toxic variety of prescription drugs, cocaine and other hypnotics were found by police as Weiland was discovered dead on his tour bus in Bloomington, Minn. A medical examiner said he died of cardiac arrest from an accidental overdose of cocaine mixed with alcohol and meth, abetted by his prolonged substance abuse.

He was buried at Hollywood Forever Cemetery eight days later.

In a 2016 Notre Dame alumni magazine, there was a short note added for those who were in the class of ’59: “Dave Weiland’s son Scott passed away in early December in Minnesota while on tour with his band.”

For those who saw him play football in high school, there can be the “What if?” ask. For those who embraced his music, that question remains as well. How will he be remembered?

“Sadly, by the end Weiland was as well known for his disease as for his art,” wrote the L.A. Times’ Randall Roberts in an appreciation story.

More intersection of sports and music in SoCal history:

There’s the backstory about the formation of Hawthorne’s legendary group, The Beach Boys, and includes the tale about how on the Cougars’ 1957 B Team, halfback Al Jardine suffered a broken leg during a November game when quarterback Brian Wilson called one play and ran another, pitching the ball to an exposed Jardine who was swallowed up by two defenders.

Wouldn’t it be nice if Brian Wilson could have just found piece of mind just playing sports?

Turns out, it was. He explained in an 1988 New York Times magazine piece about growing up on the East side of Hawthorne, near the city’s small airport and what amounted to an industrial tract not far from Inglewood:

”It was the damned boondocks. I walked around paranoid that somebody was going to pound the hell out of me every second. The kids were bullies, angry and insecure about living in this ugly place instead of Malibu or Beverly Hills or Santa Monica. I tried to escape with sports like football, and I was a quarterback on the second-string team, but the punishment and competition were too much and I quit the squad. Then I tried baseball, which I loved, because I used to stand out there in center field and kinda sing to myself in between pitches.”

According to BecomingTheBeachBoys.com, both Jardine and Wilson made the B team their sophomore year of 1957 at Hawthorne High.

In a game at Culver City, with Hawthorne comfortably ahead and about to post a 45-13 win, coach Otto Plum began sending in second- and third-string players to give them experience. Wilson was sent in as quarterback and Jardine as fullback. A play called for Wilson to pitch the ball to Jardine. Wilson was confused by the blocking, made it a short toss, and Jardine was left holding the ball without protection.

Bob Barrow, who played on the B team that year, recalled: “They put Al on a stretcher and put him on the side of the field. He laid there until the game was over and he came back with us on the bus. It was a traumatic fracture of his femur. I think today they would have hauled him off in an ambulance. I understand when he arrived at the hospital they had to cut off his football pants.”

Years later, Jardine recalled: “Our half back confessed to me it was his fault. He interfered with Brian’s ability to get the ball to me because he ran into the wrong hole. And Brian had to turn the other way. Well, I saw Brian turn the other way, so I assume, you know, he blew the play. It was supposed to be a pitch left, a real simple pitch out. And I kept waiting and waiting and waiting. What the heck, why’s he going the other way? And then Brian lobbed it to me. He just threw it to me instead of pitching it to me. And God, this guy was —anyway, it was pretty obvious where it was going. And Brian’s been living with that for, oh, like 50 years. Yeah, that was pretty serious. It must have been traumatic. I know it was for me.”

At the start of their junior year in fall 1958, Jardine stayed on the B squad but Wilson moved up to varsity as the third-string quarterback. Both played varsity in 1959 as seniors, but at some point in the season, Wilson left the team to focus on his music.

In 1971, brother Carl Wilson recalled: “Brian was a tremendous student. He was interested in music more than anything, but he was into sports quite a bit. He was really a very good athlete. He quit the football team his senior year and the coach got so pissed off at him he wouldn’t talk to him for the rest of the year.”

That coach was Hal Chauncey, who loved to boast: “Al Jardine was my hard driving fullback. Big Al Jardine — all 145 pounds of him. I’m lucky we didn’t get him killed. But he didn’t realize he was 145. He thought he was 200 pounds and played like it.”

In the school newspaper, The Cougar, Jardine was listed as 5-foot-8 and 165 pounds. Hawthorne built a team in Chauncey’s last season of 1959 that would go all the way to the CIF title game, with Jardine as one of its prime ball carriers.

In a Week 3, 30-14 win over Inglewood, Jardine scored on a 4-yard TD run and carried 14 times for 60 yards. In a Week 7 win over Morningside that pushed Hawthorne to 6-0, Jardine had 95 yards on 21 carries. After the Cougars posted an 8-0 regular-season run and won the Bay League title, Jardine was voted Most Improved Player at the varsity awards ceremony.

In a CIF semifinal win over Glendale, Jardine had three carries for 33 yards (one of them a 30-yard run). That put Hawthorne in the title game before some 14,000 at the L.A. Coliseum. The Cougars endured a 42-20 loss to Long Beach Poly, which had future USC and NFL tailback Willie Brown, the CIF Player of the Year Brown had 13 carries for 124 yards against the Cougars.

Jardine’s stats: One carry, 5 yards. He had more to carry later.

Jardine, the only original member of the Beach Boys who wasn’t part of the Wilson family core, played guitar and met up with Brian Wilson after their Hawthorne High graduation. Brian introduced him to the band. He was in — even though he went to dental school, but returned after the group launched, perhaps because Jardine’s mother had loaned the kids money to get instruments.

Who else wore No. 3 in SoCal sports history?

Make a case for:

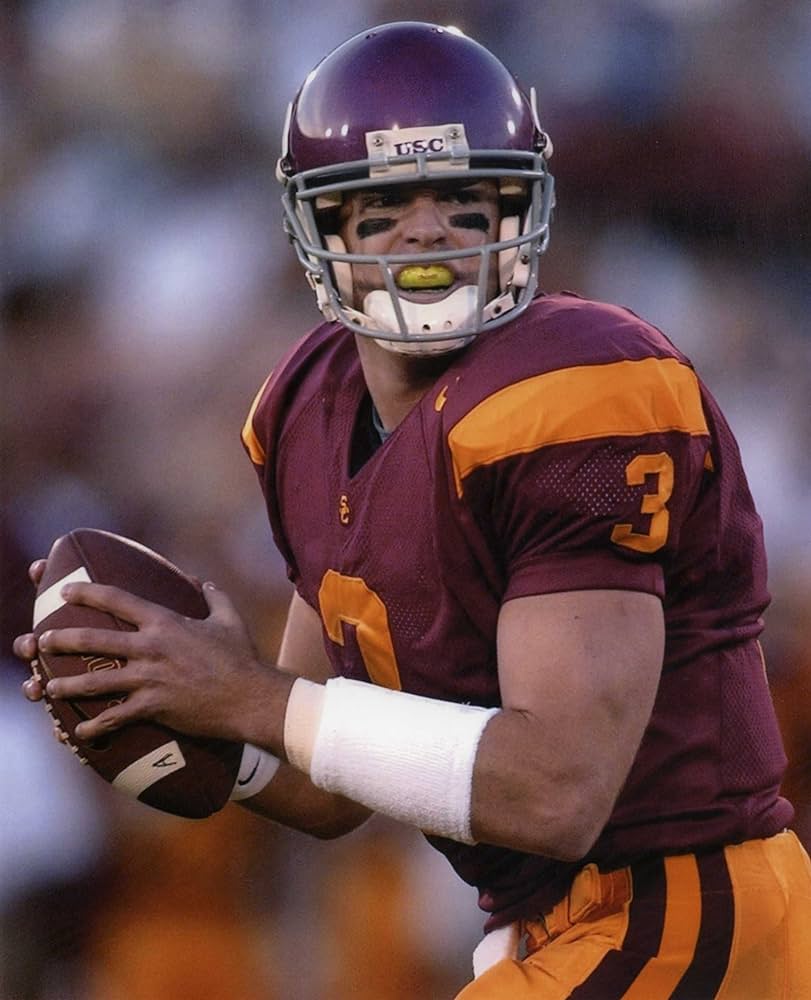

Carson Palmer, USC quarterback (1998 to 2002) via Rancho Santa Margarita High (1994 to 1997)

Best known: USC’s first four Heisman Trophy winners were running backs, so it was a turning point in the program’s history when the 6-foot-5 strong arm out of Santa Margarita Catholic High in Rancho Santa Margarita set 27 Trojan records and became not only the first USC quarterback honored, but also the first player from the West Coast in more than 20 years. As the final weeks of the 1997 season saw him establish himself as the school’s all-time passing leader with a 448-yard, five-TD game against No. 14 Oregon, that was followed by a win in Week 11 over No. 25 and rival UCLA (19 of 32 passing, 254 yards, four TDs, as he became the conference career leader in passing) and a Week 12 triumph over rival Notre Dame (425 yards passing, the most ever against the Irish in its history, to go with four TDs). Palmer had racked up 3,942 yards and 33 TDs against 10 picks as a senior, leading USC to a win in the Orange Bowl over No. 3 Iowa as the game MVP. It led to him becoming the No. 1 overall choice of the Cincinnati Bengals in the 2003 NFL Draft.

Not well known: Palmer set or tied 33 Pac-10 and USC records in five seasons at USC — he played three games in what started as his sophomore season of 1999 but was injured and allowed to redshirt, but keep the stats. That pushed him to 11,388 yards passing and 71 touchdowns in his career with a quarterback rating of 131.2. After his playing days, Palmer allowed transfer wide receiver Jordan Addison wear the No. 3 jersey in 2022, the same number he had at Pitt for two seasons, even thought it had been retired in Palmer’s honor. “He promised to work his tail off and represent all that it means to be a Trojan, and that he’d be incredibly humbled to wear No. 3,” Palmer said. This was the same Palmer who arrived at USC under coach Paul Hackett and had wanted to wear No. 3 so bad he switched to it after his freshman season when it became available.

In 2024, Palmer returned to Rancho Santa Margarita to become the program’s head coach, where his son was playing. Palmer broke dozens of records for the school while playing there in the 1990s, leading Santa Margarita to consecutive Division V state titles in 1996 and 1997. His son, Fletch (wearing No. 15), is a freshman quarterback at Santa Margarita, which Palmer led to a CIF Open Division state title win in 2025 with a dominant 47-13 decision over perennially dominant Concord De La Salle.

Keyshawn Johnson, USC football receiver (1994 to 1995):

Best known: Johnson’s two seasons at USC — coming out of L.A.’s Dorsey High and two years at West L.A. College to get his grades up — resulted in just 16 total touchdown catches, and 12 of them in 22 regular-season games. But it was the 66 catches for 1,362 yards as a junior and 102 receptions for 1,434 yards as a senior (and a seventh-place finish in the Heisman race) that dazzled enough scouts to make him the No. 1 overall pick of the New York Jets in the 1995 NFL Draft (where the team was instructed to “just give me the damn ball“). Add to that his performance in big games: The two-time All American was named MVP of the 1995 Cotton Bowl as a junior and the 1996 Rose Bowl as a senior. In the later, he caught 12 passes for a Rose Bowl record 216 yards and a TD in USC’s 41-32 win over Northwestern. He was inducted into the Rose Bowl Hall of Fame in 2008.

Not well known: In a 2020 New York Times list of the “best players to wear every jersey number in college football history,” Johnson was tops at No. 3 over USC’s Carson Palmer and Notre Dame’s Joe Montana.

Josh Rosen, UCLA quarterback (2015 to 2017):

Best known: A five-star recruit out of St. John Bosco in Bellflower, Rosen became the Pac-12 Freshman Offensive Player of the Year as the first true frosh to start a season opener for the Bruins — completing 28 of 35 passing for 351 yards and three TDs in a 34-16 win over Virginia. He also set a school record with 199 consecutive passes without an interception. The highlight of a sophomore year was a career-best 400 yards passing in a loss to Arizona State. As a junior, he opened the season, during a 45-44 win over Texas A&M, by throwing for 491 yards and four touchdowns to overcome a 34-point deficit. After five games, he led the nation in passing (2,135 yards) and touchdowns (17) and ended up eclipsing Bred Hundley’s single-season school record with 3,740 yards. But that was that. Rosen jumped to the 2018 NFL Draft, became the 10th overall pick by Arizona, and dug in by proclaiming those drafted ahead of him were “nine mistakes.” That group included No. 1 overall Baker Mayfield of Oklahoma (to Cleveland), No. 3 Sam Darnold of USC (to the N.Y. Jets) and No. 7 Josh Allen of Wyoming (to Buffalo). As of the 2026 playoffs, Darnold was calling signals for the NFC No. 1 seed Seattle, Allen was an MVP candidate for the AFC No. 6 seed Buffalo, and Mayfield, after two Pro Bowl seasons in Tampa Bay, had the Bucs tied for the NFC South title but didn’t get them into the postseason. Rosen, 3-10 as a starter in Arizona as a rookie, went to Miami the next year (0-3 in six games), sat out 2020 and came back for one final year in Atlanta (no starts in four games, 2-for-11 passing). Rosen was 24 when his pro career ended. He has been working as an investment banker after getting an MBA from Wharton.

Not well known: His given name is Joshua Ballinger Lippincott Rosen, aka the “Chosen Rosen.”

Willie Davis, Los Angeles Dodgers center fielder (1960 to 1973):

Best known: The “Three Dog” out of East L.A.’s Roosevelt High — a nickname that matched up his wearing No. 3 and his success rate hitting balls into the gaps that he turned into triples — effectively became next up as the Dodgers center fielder after Duke Snider’s retirement. Things often came in threes for Davis. He was a three-sport standout in high school, running a 9.5-second 100-yard dash and setting a city record in the long jump. A three-time Gold Glove winner, Davis made the N.L. All-Star roster twice during his final three seasons in L.A. His 31-game hitting streak remains a franchise record. Dusty Baker, who grew up in Riverside and won a World Series with the 1981 Dodgers, once said: “We all wanted to be Willie Davis. He ran like a gazelle the way he would fly around the bases. We all tried to imitate him. We thought he was the coolest dude ever.” Davis remains the Los Angeles Dodgers’ career leader in hits (2,091), runs (1,004) and triples (110) and is third all-time with 335 stolen bases.

Not well known: Davis, who accumulated 2,561 hits in his 18-year career and stole 384 bases, has the highest career WAR (60.8) never to appear on a Hall of Fame ballot. According to the JAWS statistic — which is sabermetrician Jay Jaffe’s calculation to measure a player’s Hall of Fame worthiness using their career WAR averaged with their 7-year peak WAR — Davis is No. 16 of all-time center fielders. Davis’ JAWS stats are better than 14 players currently in the Hall, including Kirby Puckett, Larry Doby and Hack Wilson.

Also not well known: Davis is the biological father of former MLB outfielder Eric Anthony, born in 1967 in San Diego (a team Davis eventually played for in 1976). Anthony had a nine-year career that ended with him playing center field with the Dodgers in 1997, wearing No. 27. Anthony has tried to campaign to have Davis’ career re-evaluated by HOF veteran voters. “Willie has not been given the respect he deserves in his career,” Anthony said. “Look what he has done. I mean, at the very least, he should have his number retired by the Dodgers. Nobody should be wearing No. 3 again.’’

Not well known: Davis was given No. 26 by the Dodgers for his major league debut with a September call up in 1960. In a 20-year pro career that included two seasons in Japan, Davis came back at age 39 to play his last season with the California Angels, wearing No. 24.

Steve Sax, Los Angeles Dodgers second baseman (1981 to 1988):

Well known: The NL Rookie of the Year in 1982 had three NL All Star seasons with the Dodgers, stealing as many as 56 bases in 1983 — the same season he piled up 30 errors, also a career high, ranking third-worst overall in the league and tops among second baseman. He also led NL second baseman in errors with 22 in ’85, was second with 19 in ’82, and third with 14 in ’87 and 21 in ’84. It wasn’t so much the glove work, but mostly the arm and the ability to throw the ball with some measure of accurately.

Not well known: The story goes that when Sax left the Dodgers after eight seasons as a free agent, following the team’s 1988 World Series triumph, he asked his new team, the New York Yankees, if he could keep his No. 3. Well, no. See, a guy named Babe Ruth had it, and the franchise retired it. He took No. 6 instead, since retired by the Yankees — not for him but eventual manager Joe Torre. Not to blow his own horn, but Sax is also credited with writing a book about his life, “Sax!” captured in 1981, followed up by a 2010 self-help manuscript called “Shift: Change Your Mindset and You Change Your World,” which is endorsed on the cover by Donald Trump. Please have someone proofread for any obvious errors.

Anthony Davis, Los Angeles Lakers center (2019-20 to 2023-24):

Best known: During his first season in L.A. — the Lakers swung a three-team trade with New Orleans and Washington by dumping seven total players, two first-round draft picks and a second-rounder to get him — Davis was an All-Star, a leading candidate for Defensive Player of the Year and, at 26.7 points per game, the leading scorer on a LeBron James-led that had the best record in the Western Conference prior to the season’s suspension due to COVID. In May 2023, during the Lakers’ Game 1 Western Conference semifinal series against Golden State, Davis posted one of the most statistically staggering games in team history — 30 points, 23 rebounds and four blocks, joining Elgin Baylor, Wilt Chamberlain, Kareem Abdul-Jabbar and Shaquille O’Neal as the only other Lakers to reach those markers in a post-season contest. When the Lakers won the 2023 inaugural NBA Cup — the in-season tournament with a stand-alone title game in Las Vegas, Davis had 41 points, 20 rebounds, five assists, plus four blocks. Before that, the only Laker players with a 40/20/5 game in franchise history were Baylor and Chamberlain. Later that season, Davis, despite dealing with a shoulder bruise, became the first NBA player to have at least 27 points, 25 rebounds, seven steals, five assists and three blocks in a single game. Davis’ five-plus years with the Lakers ended abruptly on Feb. 2, 2025 when h was part of a surprise three-team trade that involved Luka Doncic coming to L.A. from Dallas.

Not well known: After coming to L.A. from New Orleans, Davis was promised to eventually get to wear the No. 23 he had going back to his college days. Davis said that he wore it not as a tribute to Michael Jordan (as many other NBA players did), but it was in deference to LeBron James. With James now in L.A. and vowing to bequeath his No. 23 to Davis, as a gesture of thanks for “The Brow” to becoming his teammate, all it needed was NBA approval. That didn’t happen because it had too many “James 23” jersey stocked on its sales racks. Davis was given No. 3 as a placeholder, but ended up keeping that through his time with the Lakers.

Candace Parker, Los Angeles Sparks forward (2008 to 2020):

Best known: Drafted No. 1 overall by the Sparks out of Tennessee, the 6-foot-4 Chicago native was the WNBA’s MVP and Rookie of the Year from the start, averaging 18.5 points, 9.5 rebounds and 3.4 assists. She won another MVP Award in 2013 (17.9 points, 8.7 rebounds, 3.8 assists) and was the 2016 WNBA Finals MVP after the Sparks won the title. The Sparks retired Parker’s No. 3 in a ceremony in June of 2025.

Not well known: In July of 2024, ESPN posted the Top 100 pro athletes of the 21st Century. Parker was listed as No. 60. Her bio read: “Three-time WNBA champion, 2016 Finals MVP, two-time Olympic gold medalist, two-time WNBA MVP, seven-time All-WNBA First Team, 2008 WNBA Rookie of the Year, 2020 WNBA Defensive Player of the Year, two-time NCAA champion, two-time Final Four Most Outstanding Player, 2007 Wade Trophy winner. … Parker was known for being able to play any position, but at 6-foot-4 she was lethal as a post player with a diverse skill set. In college, Parker led Tennessee to coach Pat Summitt’s last two NCAA titles, in 2007 and 2008. The No. 1 WNBA draft pick by the Sparks in 2008, Parker had an epic first pro season: She was MVP and Rookie of the Year (no other player has done that) and won Olympic gold. She spent 13 of her 16 WNBA seasons with the Sparks, but won WNBA titles with Los Angeles, Chicago and Las Vegas.”

Chris Paul, Los Angeles Clippers guard (2011-12 to 2016-17, 2025-26):

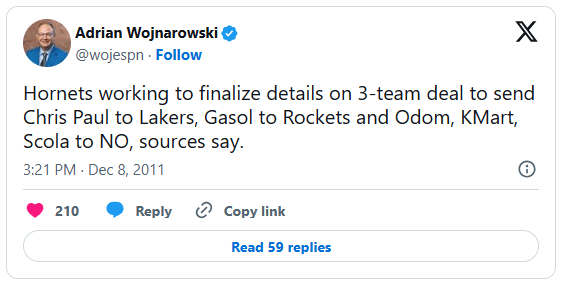

Best known: On Dec. 8, 2011, Yahoo! Sports’ Adrian Wojnarowski broke the news that, coming out of the NBA player lockout, the Lakers made a deal to obtain New Orleans Hornets guard Chris Paul as part of a three-team trade, Four hours later, the deal was off. Lakers governor Jeanie Buss revealed the trade collapsed due to miscommunication between NBA commissioner David Stern and Dell Demps, New Orleans’ general manager. This was a time when a collective of NBA owners controlled the owner-less Hornets, and several individuals spoke up that the Lakers were exploiting this situation with another deal that strengthened their status. Sure, had things broken the Lakers’ way, Paul would have been in the backcourt with Kobe Bryant. A few days later, Paul did come to L.A. As a Clipper instead.

Paul, plus $350,000 in cash and a 2015 second-round draft pick were part of the Clippers’ haul in exchange for Chris Kaman, Eric Gordon, Al-Faroque Aminu and a 2012 first-round pick that ended up being Austin Rivers. His first year with the Clippers, he was third in MVP voting, first-team All-NBA and first team All Defense. During his six seasons with the “Lob City” Clippers, Paul was a five-time All Star, twice leading the NBA in assists and three times in steals. At age 33, the 2006 NBA Rookie of the Year was traded to Houston for seven players, $661,000 in cash and a 2018 first-round draft choice, starting him on a six-team, eight-season odyssey that landed him back with the Clippers for what would be declared his 21st and final year at age 40. But as the team started 5-16 in ’25-’26, and Paul, a seldom-used reserve, wasn’t content with his role, the Clippers decided to cut him loose, announcing it in the middle of the night during an East Coast road trip. The future Hall of Famer stands second in the NBA all time in assists and steals.

Not well known: Paul wore No. 3 since his days at Wake Forest because his father and brother also have the initials C.P., so he is the third.

Odell Beckham Jr., Los Angeles Rams receiver (2021):

Best known: The Rams were off to a 7-3 start during the 2021 season when they took a flyer on the mercurial three-time All-Pro who had just been released by the Cleveland Browns. The Rams worked him into the system for eight games that resulted in 27 catches for 305 yards and five TDs. The payoff seemed to be during the Rams’ eventual 23-20 Super Bowl LVI win Cincinnati. After Beckham caught a 17-yard touchdown pass from Matthew Stafford for a 7-0 lead, and then pulled in a 35-yard reception from Stafford early in the second quarter, a knee injury later in the quarter sidelined him the rest of the game. He left the Rams after the Super Bowl, sat out all of 2022, and came back for brief stints with Baltimore and Miami.

Not well known: The signing Backham cost the Rams a reported $4.25 million. Beckham said he was getting paid in cryptocurrency.

Paul Krumpe, UCLA soccer defenseman (1982 to 1985): A four-year starter with the Bruins, Krumpe, a standout from West Torrance High, was co-captain of the 1985 NCAA championship team and held the school record for single-season assists by a defender with 10 in ’85, including the game-winner in the title game. Krumpe spent three seasons as an assistant at UCLA as the team went 56-9-1 and won the ’97 national title. He was the head coach at Loyola Marymount from 1998 to 2021.

Kelly Claes Chen, USC women’s beach volleyball (2014 to 2017): A two-time All-American and three-time national champion in the sport, the redhead from Fullerton partnered with Sara Hughes to form one of the most dominant teams in college sports. The pair expect to compete in the 2024 Summer Olympics in Paris.

Elmore Smith, Los Angeles Lakers center (1973-74 to 1974-75): Wilt Chamberlain and Bill Russell were routinely credited with games of 20-plus blocked shots, but it wasn’t an official stat until 1973-74 — Smith’s first season with the Lakers, after he arrived from the Buffalo Braves. During his time in L.A. after Chamberlain and before Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, Smith set the NBA single-game record with 17 blocks against Portland on Oct. 28, 1973 (to go with 12 points and 16 rebounds for a unique triple-double rarely seen). Eleven blocks in a half also set an NBA record. The 7-footer from Kentucky State whose nickname became “The Rejector” would lead the NBA with a 4.8 blocks-per-game average that first season. As part of a deal to get Abdul-Jabbar to L.A., Smith was traded to Milwaukee before the ’75-’76 season.

Have you heard this story?

Glenn Burke, Los Angeles Dodgers outfielder (1976 to 1978):

In parts of three Major League Baseball seasons in Los Angeles, Glenn Burke showed flashes of his speed and power. His contribution to pop culture was an impromptu creation of the high-five celebration. But suddenly he was banished. His story has been told on various literary platforms:

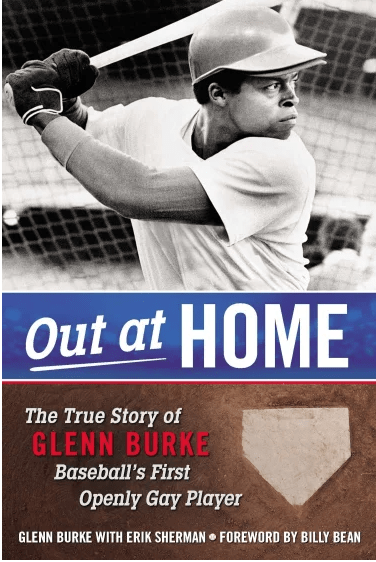

The autobiography: In 1995, as Burke was experiencing his final days, Erik Sherman had spent months with him and figured out a way to self-publish a manuscript that gave the Oakland native a platform by which to explain what he had been through.

As explained in the obituary above, Sherman released parts of his book to the Associated Press so it had the more accurate material to include.

“You take a great risk when you self-publish,” Sherman said, explaining that he feared a lawsuit might be filed by someone in the Dodgers’ family who took offense to what Burke said was done to him. That didn’t happen.

“It’s a somber day, but also a day of relief because his family and friends know he’s at peace with himself,” Sherman said at the time. “The doctors didn’t give him past Christmas. He’s been hanging on for months.”

Sherman could later add as context: “The thing that kept going through my mind was how unfair it was for him because he loved baseball. If there is a legacy for this book, it is, if you can play at the major league level, then your teammates don’t care if you are gay.”

Twenty years later, Penguin Publishing reissued “Out at Home” at a time when there was more open discussion about athletes and the LBGTQ community. The publishers explained in their book synopsis: “Before Jason Collins, before Michael Sam, there was Glenn Burke. By becoming the first—and only—openly gay player in Major League Baseball, Glenn would become a pioneer in his own way, nearly thirty years after another black Dodger rookie, Jackie Robinson, broke the league’s color barrier. This is Glenn’s story, in his own words .”

The Young Adult title: In 2021, Andrew Maraniss took it a step further. He repurposed material from Sherman’s work and created a narrative for middle- and high-school aged readers with “Singled Out: The True Story of Glenn Burke: The First Openly Gay MLB Player and Inventor of the High-Five,” which Penguin/Random House published. In using the YA format, Maraniss still captured a mature telling of Burke’s story.

“I interviewed dozens of people for this book and did essentially the same type of research that I would have done for an ‘adult’ book,” Maraniss told me. “I feel that there is room for more good narrative non-fiction aimed at teens, particularly that involve sports. I love visiting schools and telling these stories about sports and social justice. It means a ton to me when a teacher or librarian comes up and says ‘this student doesn’t ordinarily read much, but he or she loved your book.’ I feel that given the state of the world right now it’s important to reach young people with stories that shine a light on injustice and encourage them to use their voices to make change. My hope is that the audience for this book is actually expanded, rather than limited, by aiming it at both high school students and adults.”

Maraniss said his takeaway from the story is a passage he uses toward the end of the book, when the pastor speaks at Burke’s funeral and says that Glenn “died in truth. He told the truth. He didn’t live a lie, and I believe the truth sets people free.”

“And then I write: ‘In that proclamation resides the paradox of Glenn Burke’s life, and the lesson to us all. Allowed to be his authentic self, Glenn embodied achievement, innovation, love, humor, friendship, freedom, and compassion. But when powerful elements of society told him that was unacceptable, that he must somehow instead deny a fundamental aspect of his being, his life devolved into one of confusion, lies, ambivalence, anxiety, seclusion, and self-destruction. What clearer evidence do we need that homophobia, like other hatreds, not only deprives individuals the ability to become their very best selves, but also robs the world of their gifts?’ ”

The children’s book: In February of 2024, “Glenn Burke, Game Changer: The Man Who Invented the High Five,” was released by MacMillan Publishing, written by Phil Bilder and illustrated by Daniel J. O’Brien. The target reader age is 6 to 9.

“It recognizes the challenges Burke faced while celebrating how his bravery and his now-famous handshake helped pave the way for others to live openly and free,” according to the publisher’s press release.

In 2020, Bilder also wrote “A High Five For Glenn Burke” as a piece of fiction. It crossed our radar for a review, telling the story of a kid who was questioning his own true self in the setting of his Little League team. It was intended for ages 10-13/Grades 5-7. In the acknowledgements, Bildner, a former New York City public school teacher, gave a shout out to “Kevin, my husband. My husband. Words a previous, self-hating version of me would’ve never been able to process, comprehend or accept.”

Burke was known more his basketball skills than his baseball IQ at Berkeley High in Oakland. The Dodgers were convinced by a local scout they could give him an opportunity for the later in 1971, as well as let him play some college baseball.

As a 17th round pick out of Merritt College in 1972, the Dodgers gave him a modest a $5,000 signing bonus and let him play in the offseason for the University of Nevada (basketball, since he wasn’t eligible to play baseball now as a professional). He scored 35 points in a 106-101 win over Stephen F. Austin in his first game and would average 16 points a game in the first half dozen games of the 1974-75 season. He then twisted a knee and would be dismissed from the team.

“Glenn Burke leaves Reno, criticizes both Padgetts,” read the headline in the Reno Evening Gazette when Burke was dismissed shortly before Christmas 1974. They were 4-2 with him and finished 6-14 without him.

“I think the problem is that Burke couldn’t adjust to the college way of life and way of playing college basketball,” then-Nevada coach Jim Padgett told the paper. “He lacks the discipline. … He hasn’t been on a coached team since high school and I stress a team effort. He just hasn’t matured.”

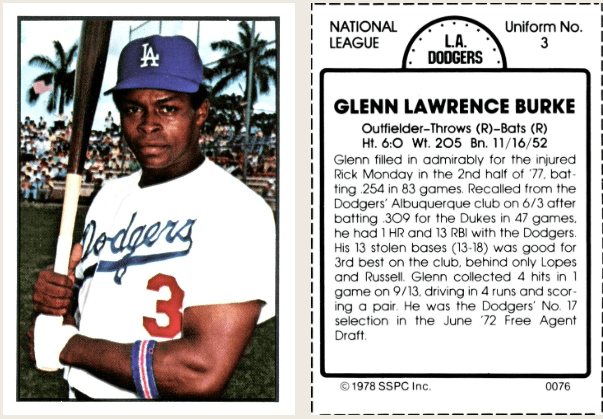

He made his debut in the first and last month of the 1976 season, as a spare outfielder playing behind Rick Monday, Reggie Smith and Dusty Baker. Burke had trouble with the curveball and hit .239 in 51 plate appearances. “Once we get him cooled down a little bit,” said the late Junior Gilliam, then a Dodgers coach, “frankly, we think he’s going to be another Willie Mays.”

After 85 games with the Dodgers in 1977, batting .254 with 13 stolen bases, he made the post-season roster and found himself in the starting lineup and hitting seventh in Game 1 of the World Series against the New York Yankees. He went 1-for-3 with a sixth-inning single, a play that ended with Steve Garvey thrown out at home plate trying to score from first. In the top of the ninth of a 3-3 tie, Manny Mota pinch hit for him. Burke got in to play in Games 2 and 5 as a defensive replacement to help protect the Dodgers’ leads in both eventual wins.

By the middle of the ’78 season, the Dodgers front office people weren’t comfortable with the way he led his life. Burke was offered $75,000 toward a honeymoon if he would just get married. “To a woman?” Burke replied.

By this point, few in the Dodgers were comfortable with the relationship Burke had with manager Tommy Lasorda’s openly gay son, Spunky.

The Dodgers swapped him out for Oakland Athletics center Bill North in a sudden traded in May of ’78. It was not popular with Burke’s teammates.

“He was the life of the team,” said Lopes. “No one cared about his lifestyle.”

“There was no justification for it,” Burke’s agent Abdul-Jalil al-Hakim told ESPN. “You couldn’t have found one player in the locker room who felt good about it, so why now and what for?”

Added Baker: “I don’t know what people are going to say why he was traded, but we knew the reason he was traded was because he was gay. You couldn’t be more blunt than that.”

Burke’s season and a half with the Athletics and manager Billy Martin wasn’t pretty. Martin, in the twilight of his career, ostracized Burke, calling him a “faggot” among other slurs, which also came from fans in the stands.

“They knew I was gay and were worried about how the average father would feel about taking his son to a baseball game to see some fag shagging fly balls in center field,” Burke wrote in his autobiography. “Martin never called me a faggot to my face. He may have known I would’ve kicked that ass.”

He was back in Triple A in 1980 for 25 games, another knee injury, then out of baseball at 27.

Three years after his MLB career was over, Burke officially come out as a gay man to the world in a 1982 story that ran in Inside Sports titled “The Dodger Who Was Gay.”

When that issue landed, there was a subsequent media-made coming-out party. A somewhat less-than-revealing Burke sit-down interview with Bryant Gumbel on NBC’s “Today” show (which apparently made Gumbel nervous, we now read). There was also an L.A. Times piece Randy Harvey did on Burke headlined “Tired of Torment, Burke Searches for Inner Peace.”

By that point, Burke had been ostracized from baseball and started using drugs to cope. His leg and foot were crushed after being hit by a car in 1987. He was arrested on drugs charges and lived on the San Francisco streets for several years. He would never really recover.

On Oct. 2, 1977, Glenn Burke created one of the most endearing celebrations in sports.

It was the last game of the regular season, as the Dodgers already clinched the NL West. With two out in the bottom of the sixth, Dusty Baker hit a home run of Houston’s JR Richard, giving him 30 to lift him into a group with Steve Garvey, Ron Cey and Reggie Smith as the first team to have four players hit 30-or-more homers.

Burke, in the on-deck circle, greeted Baker not with the usual hand slap, but held both his hands high for embrace. Baker bought into it.

Burke then went up hit his first and only home run as a Dodger.

A week later in the National League Championship Series Game 2, Baker hit a homer against the Phillies, and there was Burke — hat on backward and wearing Davey Lopes’ blue jacket — doing this “high-five” again. It became a thing.

“No, I didn’t invent the high five,” Baker said. “All I did was respond to Glenn. That’s all I did.”

An ESPN “30 For 30 Short” 10-minute piece, “The High Five” directed by Michael Jacobs, eventually helped give it context.

Baker once said about Burke: “Glenn changed me. He made me more open-minded. He made me more tolerant. He made me more generous with my time and my money. That was all because of Glenn.”

Major League Baseball used its 2014 All-Star Game as a time to recognize Glenn Burke as a “gay pioneer” and launch its own department of inclusion, eventually headed up by another former Dodgers outfielder, Billy Bean.

To frame the event, a New York Times piece by John Branch headlined “Posthumous Recognition” helped explain things better.

“He could take any moment in time and make it fun,” former teammate Rick Monday told the L.A. Times in 2013. “There was no better guy in the clubhouse, I’ll tell you that. There was no one who didn’t love having Glenn around.”

Seven years later, the Dodgers had a 2022 Pride Night event at Dodger Stadium. Burke’s brother, Sidney, threw out the first pitch wearing a Dodgers jersey with the number “03.”

“Call it closing the circle 44 years later,” Scott Miller wrote for the New York Times. “Call it righting a wrong after they drove him out of town in 1978.”

“Glenn probably would have said, ‘Dang, about time!’” Burke’s sister, Lutha Burke Davis, told Miller. “He’d be grinning from ear to ear. He would be thrilled that he was thought about that much, really.”

More about Burke’s life and times can be found in OutSports.com, a 2010 documentary, “OUT: The Glenn Burke Story” produced by Doug Harris. The Legacy Project Chicago also put up a plaque honoring Burke, sponsored by the Chicago Cubs.

When Burke was voted into the Pasadena-based Baseball Reliquary’s Shrine of the Eternals in 2015, his bio read in part:

Glenn Burke (1952-1995) was a fleet, capable outfielder for the Los Angeles Dodgers and Oakland Athletics during a four-year major league career …. He was the first big league ballplayer to publicly acknowledge he was gay. Although his public disclosure came after he had retired, Burke’s sexual preference was well known during his playing days, and he encountered widespread homophobia from locker rooms to board rooms. … Having appeared in just over 100 games for Los Angeles during parts of three seasons, Burke was sent packing to Oakland. Returning to his hometown didn’t make Burke’s life any easier. … He became active in amateur athletic competition after baseball, competing in the 1982 and 1986 Gay Games in basketball and track. Burke’s life then went into a tailspin. Cocaine addiction and an accident that crushed his leg and foot led to years of physical misery, bouts with the law, and homelessness. … A documentary, “Out: The Glenn Burke Story,” was released in 2010. “They can’t ever say now that a gay man can’t play in the majors,” Burke stated, “because I’m a gay man and I made it.”

Ben Agajanian, Hollywood Bears kicker (1942, 1946), Los Angeles Dons kicker (1947 to 1948); Los Angeles Rams kicker (1953), Los Angeles Chargers kicker (1960):

Five years younger than brother and motor sports legendary owner J.C. Agajanian, Ben came out of San Pedro High and Compton Junior College to wear No. 3 as a field-goal kicker for Dons, Rams and Chargers — the three L.A. pro teams during his window of opportunity.

Agajanian would play for 15 teams in four leagues over 22 seasons — one of only two to play in the All-American Football Conference, the National Football League and the American Football League. A year after debuting for Philadelphia and Pittsburgh in the NFL, Agajanian came back to L.A. with the AAFC Dons, who played at the Coliseum and were considered the city’s first pro team. He made 20 of 39 field goals in two seasons, leading the AAFC with 15 made in ’47. He was also on two NFL title teams — the ’56 New York Giants and the ’61 Green Bay Packers, and led the NFL in ’54 with 15 field goals in 25 attempts with the Giants. His longest kick — 51 yards, in 1962, for both the AFL’s Dallas Texans and the NFL’s Packers. His pro career actually spanned from 1942 to 1964, when he was 45, followed by another 20 years as a coach with the Dallas Cowboys.

Believe it or not, there’s more: Agajanian was known as “The Toeless Wonder.” When he was at the University of New Mexico as a kicker, he injured his right kicking foot in a freight-elevator work accident. Four toes were amputated in 1941. It forced Agajanian to kick with a special square-toed boot, and it worked. During Agajanian’s only year with the Green Bay Packers, coach Vince Lombardi lobbied the NFL to allow him to use the boot. His New York Times obituary features a photo of him in his Chargers’ No. 3 uniform.Ben Agajanian made it to age 98 when he died in Feb. of 2018. Note: While he wore No. 3 with the Rams, Chargers and Dons, this photo of Agajanian wearing No. 77 with the Rams isn’t included in any of his biographical or team records.

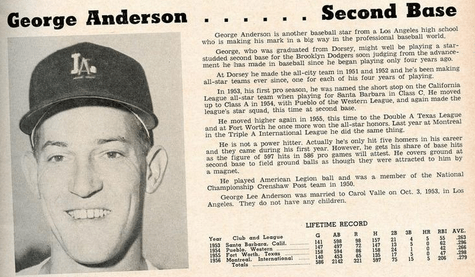

Sparky Anderson, Los Angeles Angels second baseman (1957):

The Baseball Hall of Fame manager had built himself quite a baseball history in Southern California before a Cooperstown induction — a batboy for Rod Dedeaux’s USC team, on the Crenshaw Post squad that won the American Leagion national championship team in 1950, an All-L.A. City player at Dorsey High on a team that won 42 straight games, nearly taking a USC scholarship to play for the Trojans before he signed with the Brooklyn Dodgers in 1953 and started at their Class-C affiliate in Santa Barbara. The Los Angeles Angels were a Dodgers’ farm team by 1957 — but it would be the team’s last in the Pacific Coast League as the Dodgers prepared to move to L.A. by 1958. Anderson, at age 25, was the leadoff hitter for the Angels and logged a league-high 168 games, hitting .260 for the sixth-place, 80-88 team. (Not only was pitcher Tommy Lasorda one of Anderson’s teammate, but so was first baseman Steve Bilko, who hit 56 homers with 140 RBI and a .300 average with Wrigley Field in L.A. as their home).

In ’58, the Dodgers had Anderson on their 40-man roster and the idea of staying to play another year professional in his hometown seemed like a dream. But Anderson was sent to the Dodgers’ Triple-A team in Montreal, was named team MVP, and the Philadelphia Phillies made a deal for him to make his big-league debut in 1959. Anderson’s MLB career lasted just that one season, a full 152-game rookie season, where he hit .218. Back in the minor leagues, Anderson gravitated to coaching and managing. After a year coaching with the expansion San Diego Padres, Anderson was set to become a coach with the California Angels, joining manager Lefty Phillips. The Cincinnati Reds asked the Angels for permission to see if he was interested in managing their team. Anderson, then 35, took them up on it. There rest is managerial history — World Series titles in 1975 and ’76 with Cincinnati, and in ‘1984 with Detroit over 26 years and 2,194 victories. Anderson returned to the Angels — as a part-time TV broadcaster from 1996 to ’98, after working with Vin Scully on World Series games for CBS Radio from 1979 through 1986.

Ozzie Smith, Cal State Poly San Luis Obispo shortstop (1974 to 1977): The future Baseball Hall of Famer and standout at Los Angeles’ Locke High was the San Diego Padres’ fourth-round pick out of SLO in 1977 (after he turned down a seventh-round pick by Detroit the year before when he was a junior). He set the CSPSLO school record with 110 career stolen bases, stealing 44 in a season twice. The school now gives out the Ozzie Smith Award to its most valuable player each season and his No. 3 was retired as he was inducted into the first class of the Cal Poly Athletics Hall of Fame.

We also have:

Aaron Miller, Los Angeles Kings defenseman (2000-01 to 2006-07)

Jack Johnson, Los Angeles Kings defenseman (2006-07 to 2011-12)

Curtis Conway, USC football quarterback and receiver (1990 to 1992) via Hawthorne High

Freddie Mitchell, UCLA football receiver (1998 to 2000)

James Washington, UCLA football running back (1984 to 1987)

Trevor Ariza, Los Angeles Lakers forward (2007-08 to 2008-09; 2021-22). Also wore No. 4 for UCLA in 2003-04.

Sedale Threatt, Los Angeles Lakers guard (1991-92 to 1995-96)

Devean George, Los Anglees Lakers forward (1999-2000 to 2005-06)

Gene Mauch, California Angels manager (1982): Also had No. 44 in 1981 and No. 4 in 1985 to 1987.

Cesar Izturis, Los Angeles Dodgers shortstop (2002 to 2006)

Chris Taylor, Los Angeles Dodgers infielder (2016 to 2025)

Gary Gaetti, California Angels third baseman (1991 to 1993)

Taylor Ward, Los Angeles Angels outfielder (2018 to 2025)

Anyone else worth nominating?

Great story. More people need to hear it.

On Fri, Mar 1, 2024 at 1:24 AM Tom Hoffarth’s The Drill: More Farther Off

LikeLike

Love the Willie Davis photo.

LikeLike