This is the latest post for an ongoing media project — SoCal Sports History 101: The Prime Numbers from 00 to 99 that Uniformly, Uniquely and Unapologetically Reveal The Narrative of Our Region’s Athletic Heritage. Pick a number and highlight an athlete — person, place or thing — most obviously connected to it by fame and fortune, someone who isn’t so obvious, and then take a deeper dive into the most interesting story tied to it. It’s a combination of star power, achievement, longevity, notoriety, and, above all, what makes that athlete so Southern California. Quirkiness and notoriety factor in. And it should open itself to more discussion and debate — which is what sports is best at doing.

The most obvious choices for No. 60:

= Hardiman Cureton: UCLA football

= Clay Matthews Jr.: USC football

= Dennis Harrah: Los Angeles Rams

The not-so-obvious choices for No. 60:

= Chin-Lung Hu: Los Angeles Dodgers

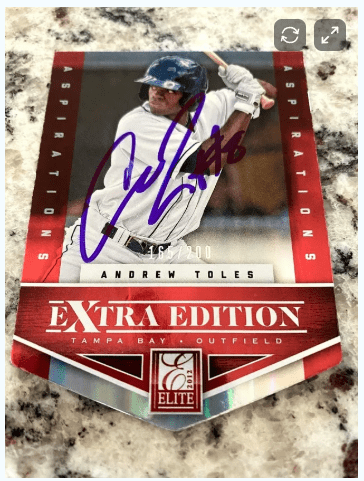

= Andrew Toles: Los Angeles Dodgers

The most interesting story for No. 60:

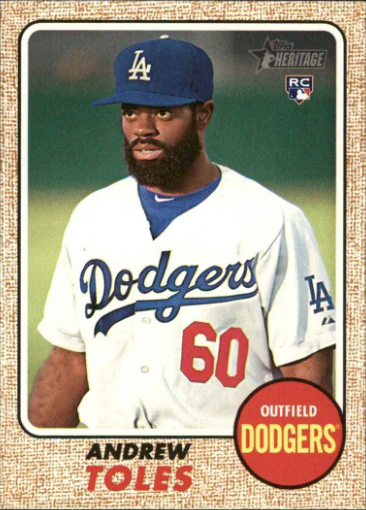

Andrew Toles: Los Angeles Dodgers outfielder (2016 to 2018)

Southern California map pinpoints:

Dodger Stadium

Every year since 2019, the Los Angeles Dodgers try to keep it under the radar about the ways they have kept Andrew Toles in their collective hearts and minds.

In his three Major League Baseball seasons, the 5-foot-9, 190-pound left-handed hitting outfielder was in just 96 games and 249 plate appearances. His. 286 batting average factors into a career 1.9 WAR. He will likely never play again, but the Dodgers have never looked at from that lens.

In years past, by renewing him as a player under contract on the restricted list, Toles and his family have had some peace of mind that his MLB health insurance will continue. Toles’ ongoing struggle with bipolar disorder and schizophrenia, likely exacerbated by a career-setback knee injury, is a daily concern to his existence.

Media reports have made it appear this is a simple action the Dodgers can take every spring, but there is far more to it. In the spring of 2026, the Dodgers eventually issued a statement of some clarification in a statement:

“We’ve been in contact with the Toles family and have worked together on how to best move forward. Continuing with the previous setup was no longer possible due to eligibility. The Toles family has asked that Andrew’s privacy be respected. Out of respect to the Toles family, we will not comment any further.”

Out of respect to this story and how the Dodgers have proceeded, it is always worthy of our attention.

The background

Andrew Friedman seemed to always have a good read on Andrew Toles.

The Tampa Bay Rays snatched up the Decatur, Georgia, native in the third round of the 2012 MLB Draft out of Chipola College in Mariana, Florida — the same draft where Oakland took Max Muncy and Seattle took Chris Taylor in the fifth round.

After his first full pro season, Toles was the organization’s 2013 minor league player of the year, hitting .326 with 62 stolen bases in 121 games, including 35 doubles and 16 triples at Single-A Bowling Green in the Midwest League.

But he showed signs of erratic frustration, threatening people around him.

Toles’ 2014 season in the Gulf Coast Rookie League and at High-Single-A ball Charlotte didn’t give the Rays any more hope. When Tampa Bay released Toles in 2015, they sensed something was wrong that they couldn’t fix. Mostly, his anxiety issues.

Toles didn’t play in 2015. The Dodgers’ due diligence led to an offer for him to join their organization in 2016. The Dodgers’ interest goes directly to Friedman — the same person who drafted and signed Toles with Tampa Bay Rays, left as its director as baseball operations in 2014 and joined the Dodgers in that same role.

Gabe Kapler, then the Dodgers’ director of player development at the time, emailed Toles to see if he was interested in returning to baseball and participating in the Dodgers’ instructional league. Toles didn’t hesitate.

“We knew Andrew experienced some personal challenges with the Rays when we signed him,’’ said Kapler. “We thought we could create a different environment that might allow him to thrive at the minor league level. There were a lot of people who cared for him and invested in him.”

Friedman knew of Toles’ circumstances, and sensed his father, Alvin, was a good influence on him.

Alvin Toles was once a first-round draft pick of the NFL’s New Orleans Saints, an inside linebacker out of the University of Tennessee, where Andrew would play baseball in 2011 as a 19-year-old (hitting .270 in 51 games). Alvin Toles’ four-year pro career ended with a severe knee injury during the Saints’ 14–10 victory over the Los Angeles Rams in mid-November of 1988. The team waived him in 1990. Andrew Toles was born two years later.

In the time when his son faced life without baseball after the Rays released him, the story goes that Alvin suggested Andrew tag along with him on his job as long-haul truck driver, taking a trip that had stops in Alabama, Kansas, Pennsylvania and Delaware. Alvin had a feeling that a few days on the road would help clarify his son’s path.

Nights spent shivering in a cot in the truck cab, showers at random truck stops and a non-stop stream of talk-radio programs left a lasting impression on Andrew.

“No disrespect to those types of jobs, but I was, like, whatever I’ve got to do, I’m going to keep going forward, because this isn’t for me,” he said.

Toles got himself in shape, focused on baseball, but needed another reminder about how the real world worked. He took a job at a local Kroeger grocery store in Georgia, the early shift in the frozen foods section that paid $7.50 an hour.

“I remember thinking, This isn’t for me, either,” he said.

Having joined the Dodgers organization in 2016, Toles’ trajectory was quick. The 24-year-old played 22 games at Single-A Rancho Cucamonga (.370 with nine steals), 43 games at Double-A Tulsa (.314 with 22 steals) and 17 games at Triple-A Oklahoma City (.321) when the Dodgers called him up that July.

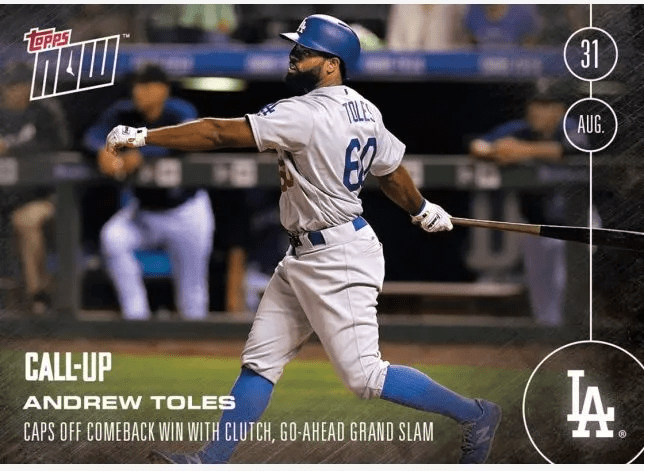

The momentum he generated during that time — including hitting an opposite-field go-ahead grand slam in the ninth-inning of a 10-8 win at Colorado on August 31– gave the Dodgers an unexpected boost as the headed toward the playoffs with an NL West title.

After Toles’ dramatic grand slam in Colorado, J.P. Hoornstra of the Southern California News Group wrote:

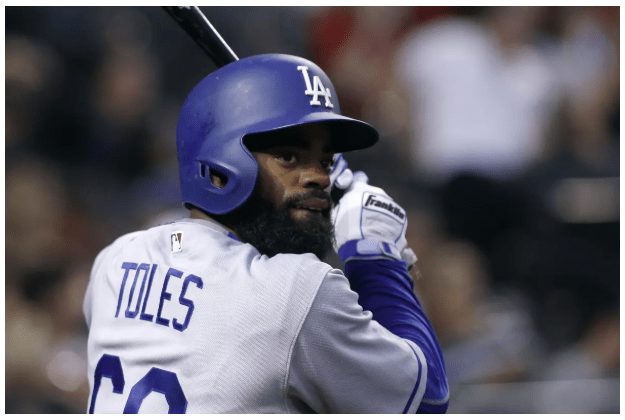

Andrew Toles, the Dodgers’ rookie outfielder, has shown dramatic versatility over his first 33 days on a major-league roster. … a gifted athlete … good baseball IQ, too. … His deadpan sense of humor, hidden behind a perpetually wide-eyed expression and a luxuriant beard, would endear him to any teammate even if he couldn’t hit worth a lick. It just so happens that Toles can hit worth a lick. With the Dodgers down to their final out Wednesday, Toles hit a grand slam to complete a stunning 10-8 comeback victory over the Colorado Rockies.

Out of baseball a year ago … Toles is now batting .397 for the first-place team in the National League West.

“He is a beautiful human,” Dodgers manager Dave Roberts said. “He’s just so calm and cool.”

After his grand slam, Toles thumped his chest on his way back to the dugout before being mobbed by his elated teammates. They were eventually able to retrieve the baseball — it was Toles’ first career grand slam and only his third home run — because it bounced back onto the playing field after ricocheting off the bleacher seats.

When Toles hit his first career homer during a recent road game in Cincinnati, he deadpanned that he might lose the baseball because, well, he loses things. How about this one?

“I don’t think I’m going to lose it,” he said.

After hitting .314 in 48 games that back half of the season — and getting to hear Vin Scully call his name during his final season before the Hall of Fame broadcaster retired — Toles started eight of 11 games in the NLDS and NLCS, going 8-for-22 with two doubles and a .364 average as the Dodgers lost to the eventual World Series champion Chicago Cubs.

By 2017 Opening Day, Toles kept a starting job in left field and batting leadoff in the Dodgers’ lineup that includes Corey Seager, Justin Turner, Adrian Gonzalez and Yasiel Puig, plus Clayton Kershaw on the mound. Toles went 2-for-5 in the opener.

In the first 30 games, he hit .271 with five homers and 15 RBIs, including a .375 average with seven RBIs in his last 11 games.

In a May 9 game at Dodgers Stadium, as Dodgers starter Julio Urias took a no-hitter into the seventh inning, Toles slid into the wall in the left-field corner trying to flag down a ball that Pittsburgh’s Andrew McCutchen would hit for a ground-rule double. Toles came out of the game for Kiki Hernandez. An MRI confirmed Toles tore the ACL of his right knee and was done for the season.

How would Toles handle this setback?

When the 2018 season started, the Dodgers made Toles the final cut on the eve of Opening Day, relinquishing his spot on the roster to Joc Pederson and Kyle Farmer.

Back at the Dodgers’ Oklahoma City Triple-A affiliate, trying to stay positive, Toles hit .306 in 71 games. He only stole three bases and was caught twice, but he hit seven homers and drove in 39.

A story posted on NBCLA noted: “For the better part of the season, Dodger fans across the country had been pining for Toles, using the hashtag #FreeToles on social media to let the front office know their desire” to see him back.

A chance occurred for that to happen in July as Puig went on the DL. Toles came up, played center field, batted eighth, went 2-for-3 with a two-run double in the fourth inning, helping Kershaw get the win over San Diego.

TrueBlueLA.com reported on the game: ”The Andrew Toles experience is full effect.”

Toles said he was “just happy to be here” and was “not going to harp on the wait (to get back) or anything.” Toles also said that the Dodge Challenger that he kept parked in the players’ lot at Dodger Stadium since the previous spring was covered in “spider webs and dust” as teammates have pointed out, sending him photos. “That thing looks gross,” Toles added.

“Everyone was excited to get him here,” Roberts added. “With Andrew, I don’t know if it really matters where he plays, as far as what level. He plays at a certain speed and doesn’t overthink things.”

A week later, Toles was back at OKC, returning for a September callup. But as the Dodgers were en-route to a 104-win season, it seemed as if they moved on without him, already fine tuned for what would be their second trip to the World Series in two seasons.

Toles only logged six more at-bats in September as a pinch hitter and occasional outfielder. In a Sept. 29 game against San Francisco, Toles pinch hit for Kershaw and singled. On Sept. 30, he, for some reason, came into play center field in the bottom of the ninth while the Dodgers were amidst a 15-0 win to clinch a tie with Colorado for the NL West.

The next day, the Dodgers had to fly home and play the Rockies in a NL West tie-breaker, Game No. 163. The Dodgers won. Toles didn’t play.

That was it. Toles wasn’t on the playoff roster as he was two years earlier.

In the 2018 offseason, the Dodgers traded outfielders Kemp and Puig, which seemed to give Toles some hope of a position.

Then Toles decided to opt out of reporting to spring training with the Dodgers in ’19. It was said to be a “personal issue.” He was put on the restricted list.

The Dodgers then seemed to lose track of him.

The reality

In early February of 2019, the Dodgers got a call from the Phoenix police.

Toles had crashed his car and was walking along a desert highway disoriented, and dangerously dehydrated, unaware of his whereabouts. He was admitted to a Phoenix area hospital. Toles’ mother, Vicky, contacted the Dodgers, seeking help.

“He recognized me in the hospital from our time together in Tampa,’’ said Dodgers medical director Ron Porterfield, who had spent 21 years with the Rays. “He said my name, but he didn’t even know how he got from L.A. to Phoenix. He asked me to take him home. I said, ‘Where are we going?’ He said, ‘To my apartment.’ But he didn’t know where his apartment was.”

Toles spent two weeks in the hospital, and Porterfield was finally granted permission to access his medical records. The courts mandated that Toles stay in a county facility, to be transferred to a behavioral health treatment center until mid-April. It was the longest stint Toles had ever spent in the hospital.

The Dodgers and the Toles’ family kept his illness and whereabouts a secret to the outside world.

In June 2020, Toles was found sleeping behind a FedEx building at the Key West International Airport in Florida. Arrested and charged with trespassing, Toles was finally diagnosed at a mental health facility. It was discovered that at that point, he had been living on the streets. His family couldn’t get him to come home.

By 2021, Toles was back in the care of his father, Alvin.

“We are having challenges, but nothing that God and I can’t handle,” Alvin told USA Today.

USA Today columnist Bob Nightengale followed up with a poignant, insightful column about the whole situation, and more.

“It was a disturbing picture, a police mug shot, spattered across the internet last weekend, revealing a troubled man with a vacant, soulless look. He looked disheveled, with hair that looked like it hadn’t been combed in weeks, if not months. His thick beard was scraggly, covering most of his face, flowing right into his hair.

“When the news came out, the response from the public was very different from the response from my family,’’ Morgan Toles, Andrew’s sister, told USA Today Sports. “When people saw my brother’s mug shot, it was like, ‘Oh, my God! He’s been arrested.’

“You know what my family felt? Relief.

“It’s really crazy to say, but the mug shot, really, was the best thing ever.

“We didn’t know whether he was dead or alive.’’

Just two weeks earlier, a similar incident occurred in Kentucky.

Toles even spent a month in prison in Hong Kong, wandering the streets after losing his passport, arrested for stealing food at a gas station. He was released after brother Morgan Toles obtained help from the U.S. Embassy. Yet, when Andrew returned to states, he disappeared again.

“The last time I saw my brother, I don’t even know,’’ Morgan says. “I haven’t heard his voice in, Lord knows how long. The only difference in my brother and the homeless walking the streets in L.A. is that he made money. That’s it. We want to help him so badly. We are doing everything we can. But the loved ones are the ones he runs from. How do you help somebody that doesn’t want to be helped?”

The circumstances

A post on Psychiatrist.com, noting the Toles’ story, reports that the average potential life lost for each person with schizophrenia is 28.5 years.

Patients with schizophrenic symptoms are at high risk for suicide as well as other medical conditions including heart disease, liver disease, and diabetes. Every person diagnosed with schizophrenia at age 25 carries a total lifetime cost to the economy of approximately $3.8 million. That’s a cost of $92,000 per patient per year.

Bipolar disorder also bears a high economic and personal burden. One analysis estimated the per-person total lifetime costs of BD ranged from $11,720 for a single manic episode to $624,785 for chronic disease. Patients with BD often have numerous other health issues like high blood pressure and drug addiction. Their condition affects their ability to work and care often comes with a huge price tag.

Fortunately, more with serious mental conditions are covered by insurance. The national uninsurance rate for adults under age 65 with schizophrenia decreased by 50 percent after the implementation of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) in 2014. According to this report, the rate of uninsured people with schizophrenia now stands at around 4 percent.

Alvin Toles said his son had been “zombie-like.” His sister said Andrew has been in more than 20 mental health facilities over the past four years.

“Schizophrenia, it’s just so tough,” said Alvin Toles. “I mean, he can’t even watch TV. He hears voices and the TV at the same time, so it’s kind of confusing. I’ve seen him looking at some baseball games on his laptop, but I don’t think he really understands what’s going on. I just want him to have a chance in life. That’s all. Just to be healthy, live a normal life.

“I’ve seen him looking at some baseball games on his laptop, but I don’t think he really understands what’s going on.”

The legacy

Andrew Friedman called Toles’ situation “heartbreaking, literally heartbreaking … I have a long history with Andrew, and I just wish there was something more we could do to help.”

This is what the organization has kept trying to do as Toles turns 34 years old this May 24.

After the 2017 season, pitcher Tom Koehler signed with the Dodgers, having logged six seasons with Miami and Toronto. He injured his shoulder in spring training. He never got to pitch for the Dodgers. He retired officially and became a certified MLB agent. He applauded the Dodgers’ actions when it came to helping Toles.

Steve Dittmore, who in 2025 wrote a well-received biography about the Dodgers’ Jim Gilliam, used a Substack post in 2021 titled “Why I am rooting for Andrew Toles” to each a sentiment felt by many. Dittmore and his son got into minor-league player autograhs, primarily from the Dodgers’ Double-A Tulsa Drillers.

Toles signed a card for them.

“I remember Toles looking back at my son in a manner which suggested surprise that someone identified him on May 23, 2016 in Springdale, Arkansas,” Dittmore wrote. “He was quiet and shy, but politely signed the card above, with his Drillers number 8. Toles was stoic in warmups and on the field, very business-like. His high socks stood out, perhaps a nod to the Negro Leagues.”

After recounting Toles’ life through his MLB journey with the Dodgers and what followed, Dittmore continued:

“I was relieved to know Toles was getting help, and I sincerely hope that it works. I do not know Toles, except for our brief interaction … nor do I know his family. I am a baseball and Dodgers fan, so, of course, this story hits closer to home for me. But I am also a father and husband who tries really hard to model behavior as an empathetic human being, treating strangers with respect. We all have our personal challenges and I try to remember that I do not know what someone else is going through when I meet that person.

“Mental health issues are critically important to our society. We should not stigmatize individuals confronted with challenges such these. We should lend them support and encourage them to seek help from professional counselors.

Athletes grow up with their identities wrapped up in being an athlete. They can be lionized on high school campuses. Colleges even single them out as “student-athletes” so as to denote their different status from being just a “student.” Kids and adults (my house is guilty) want their autographs. Academic literature increasingly focuses on this phenomenon of athlete identity and what happens when that identity is discontinued or taken away. …

“As spring training gets underway, and hope springs eternal for a ‘normal-ish’ summer, let’s pause to think how we react when we ask someone ‘how are you?’ or ‘hope you are doing well.’ Do we want an honest answer? And are we prepared to help someone when we get an honest answer.”

Who else wore No. 60 in SoCal sports history?

Make a case for:

Hardiman Cureton, UCLA football guard (1953 to 1955):

Best known: The first African-American captain for the Bruins was inducted into the UCLA Athletics Hall of Fame in 2005, acknowledging his career as an offensive guard and defensive lineman. Those UCLA teams that the Monrovia High star played on went 26-4, won three Pacific Coast Conference championships and participated in two Rose Bowls. During the 1954 national championship season, Cureton was named second-team All-Coast and honorable mention All-American. As a senior in 1955, Cureton became the Bruins’ fifth-ever consensus first-team All-American. He played nine seasons in the Canadian Football League.

Clay Matthews Jr., USC football linebacker (1974 to 1977):

Best known: The Arcadia High standout may be better known as the older brother of Pro Football Hall of Fame offensive lineman Bruce Matthews and the father of former Trojan All-American linebacker Clay Matthews III.

Still, Clay Matthews Jr., a first-round pick in the 1978 NFL Draft, No. 12 overall, by the Cleveland Browns (the first linebacker chosen and the first USC player chosen), lasted 19 NFL seasons and made four Pro Bowls. Clay was the defensive coordinator at Oaks Christian High in Westlake Village when his son, Casey , played there. Matthews was inducted into the USC Athletic Hall of Fame in 2005.

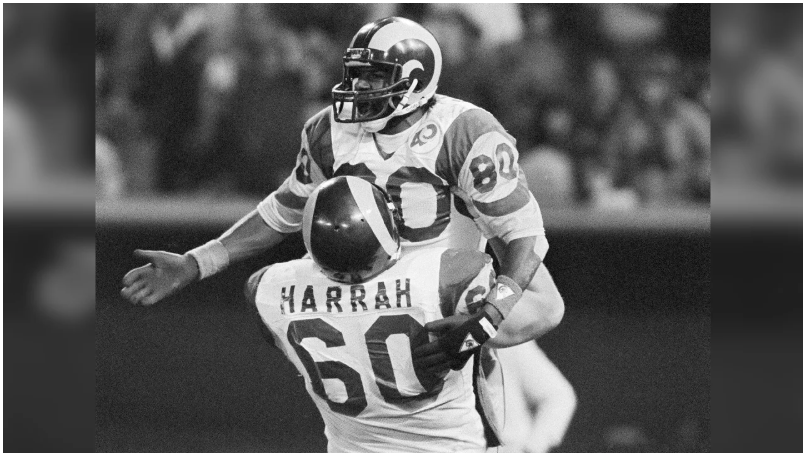

Dennis Harrah, Los Angeles Rams offensive lineman (1975 to 1987):

Best known: The Rams took him 11th overall in the 1975 NFL Draft out of Miami and saw him start 144 of his 168 games, making six Pro Bowl and part of the team’s trip to the Super Bowl in Pasadena against Pittsburgh. “The experience of playing against ‘Mean’ Joe Greene and Jack Lambert and that group, it was just, I mean, the Steelers were everything, especially being from West Virginia. I’d followed the Steelers since I was a kid,” Harrah said in 2024 of the 31-19 loss in the Rose Bowl. “But that experience for me to go against people that were going to be future Hall of Famers, it was just … The worst thing about it, I was 25-, 26-years old, and was thinking, ‘Aw, it’s no big deal. Hey, it’s the Super Bowl, I’ll be back again.’ But, you know, it teaches you after you get older to cherish every day and cherish every game and cherish every opportunity. Because you might not get another chance. And I never did.”

Have you heard this story:

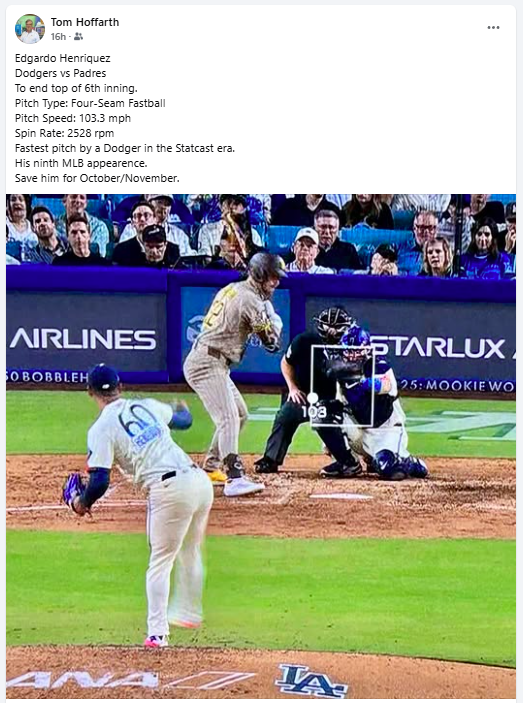

Edgardo Henriquez, Los Angeles Dodgers relief pitcher (2024 to present): On Aug. 16, 2025 this moment above happened for the 23-year-old, 6-foot-4, 200-pound pitcher from Venezuela. He pitched two shutout innings during the Dodgers’ 2025 World Series win over Toronto.

Chin-Lung Hu, Los Angeles Dodgers infielder (2007 to 2010): The last Dodgers player to wear No. 60 before Toles was this Taiwanese-born second baseman — who has the distinction of having the shortest last name in MLB history (along with Detroit’s Fu-Te Ni). He was the MVP of All-Star Futures Game in 2007 and made his Dodgers debut later that season, hitting a home run in his second at-bat. Also wore No. 14 in ’08. He became a broadcaster’s favorite player when, after reaching base, it could be said, “Hu’s on first.”

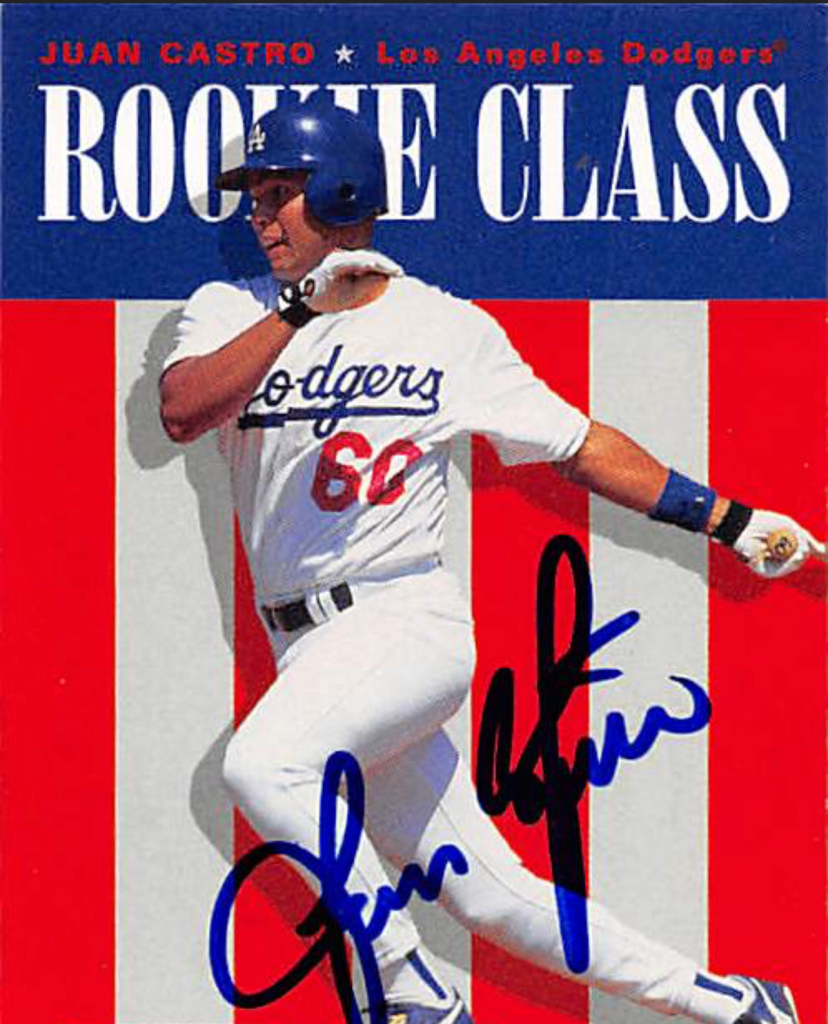

Juan Castro, Los Angeles Dodgers infielder (1995 to 1999, 2009, 2010 to 2011): Here’s the deal: Having already established that Andrew Toles and and Chin-Lung Hu wore No. 60 for the Dodgers, we also should note that more than a dozen have also sported these two oddly-paired digits. Including Castro, first when he came up as a 23-year-old rookie in ’95. He kept it one more year in ’96.

From 1997 to ’98, he switched to No. 25 — more in line with a regular player — and it was given to prospect Mike Judd. For for the end of ’98, and through ’99, Castro changed again, this time to No. 17, as Bobby Bonilla joined the team and wanted it (in ’98), but then left, and it was bequeathed to Dave Hansen. The Dodgers traded Castro to Cincinnati at the turn of the century. He bounces around, and somehow finds his way back to L.A. as a free agent. Now he’s handed a hallowed No. 14 (worn the previous season by the aforementioned Chin-lung Hu, someday to be retired for Gil Hodges). For the 2010 season, Castro joins Philadelphia. That team releases him midseason, and the Dodgers get him back. And then give him No. 33. But as Castro sticks around for his final season of 2011, he is offered a more suitable No. 3. But then Castro only makes into seven games the first three months and voluntarily retires in July, ’11. Add it up and Castro wore six different numbers with the Dodgers in his eight seasons.

Anyone else worth nominating?

Scot Schoenweis, Anaheim Angels pitcher (1999 to 2003)

1 thought on “No. 60: Andrew Toles”