This is the latest post for an ongoing media project — SoCal Sports History 101: The Prime Numbers from 00 to 99 that Uniformly, Uniquely and Unapologetically Reveal The Narrative of Our Region’s Athletic Heritage. Pick a number and highlight an athlete — person, place or thing — most obviously connected to it by fame and fortune, someone who isn’t so obvious, and then take a deeper dive into the most interesting story tied to it. It’s a combination of star power, achievement, longevity, notoriety, and, above all, what makes that athlete so Southern California. Quirkiness and notoriety factor in. And it should open itself to more discussion and debate — which is what sports is best at doing.

The most obvious choices for No. 50:

= Mookie Betts: Los Angeles Dodgers

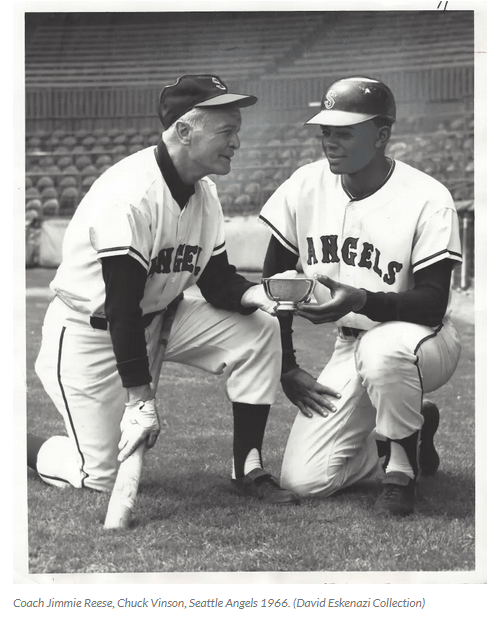

= Jimmie Reese: California Angels

The not-so-obvious choices for No. 50:

= Dave Dalby: UCLA football; Los Angeles Raiders

= Ken Iman: Los Angeles Rams

= Len Ford: Los Angeles Dons

The most interesting story for No. 50:

Jimmie Reese: California Angels coach (1972 to 1994), PCL Los Angeles Angels infielder (1933 to 1935)

Southern California map pinpoints:

San Pedro, Los Angeles, Anaheim, Santa Ana, Westwood

Where ever the fun went, Jimmie Reese’s customized fungo bat was nearby.

His customized tool of the trade for dispensing wisdom amidst pop flies to California Angels players lasted a quarter of a century.

“It was flat, so he could pop a baseball up to himself,” recalled New York Yankees manager Aaron Boone. “Just amazing.”

As a 10-year-old kid, Boone saw it first hand. He chased down fungoes hit by Reese before games at Anaheim Stadium as his father, Bob Boone, was the Angels’ catcher in the ’80s. At that time, Reese was already in his 80s.

He used his bat to actually play catch with players. He could even “pitch” batting practice — hitting balls toward the players in the batting cage as he stood on the mound.

Reese’s bat was cut in half at the top, a creation from his wood-work home workshop in Westwood. Reese’s hobby was also making custom wood frames for players to highlight milestones.

From Nolan Ryan to Tim Salmon, Reese had a yoda-like status.

The baseball world in general may have known him for joking about how he was once the traveling roommate of the Yankees’ Babe Ruth’s Yankees — at least, with Ruth’s luggage — when the two were with the Bronx Bombers in the 1930s, 10 years apart in age.

But Jimmie Reese’s true identity has a much more sophisticated backstory. It starts with his name.

On Oct. 1, 1901, Hyman James Solomon was born. He was a Jewish kid from New York with Russian Jewish immigrant parents. He was known as “Hymie.”

According to his Jewish Baseball Museum biography, Solomon came to Los Angeles after his father’s death. Enrolling at San Pedro High in the late 1910s, he changed his name to Jimmie Reese. The intent was to avoid prejudice as Jews in the United States were targeted during the start of World War I.

In a “Jews and Baseball” research piece for the Society of American Baseball Research, Peter Dreier noted that prior to the 1930s, many Jewish ballplayers changed their names in the wake of anti-Semitism. It was exacerbated by the 1919 Black Sox Scandal where gamblers Arnold Rothstein and former featherweight boxing champion Abe Attell, both Jews, were implicated in the fix of Chicago White Sox players throwing the series to the Cincinnati Reds. The charge was amplified by auto magnate Henry Ford, blaming Jews for the entire scandal in his anti-Semitic newspaper, the Dearborn Independent. In one article, Ford wrote, “If fans wish to know the trouble with American baseball, they have it in three words — too much Jew.”

On his Baseball-Register.com official page, James Herman Reese is the official name listed. When he died in Santa Ana in 1994 at age 92, the small grave marker at Westwood Memorial Park says simply “Jimmie Reese 1901 to 1994.”

Reese recalled playing three seasons at San Pedro High for coach Karl Haney, but, in an 1985 interview, he wasn’t sure what year he graduated. His best guess was 1921.

The start of his 78-year run with baseball happened when he became a batboy for the Pacific Coast League’s Los Angeles Angels in 1919, where games were played at Washington Park near downtown L.A. Reese was a “quick, blond youngster with a dazzling smile and boundless energy,” according to a SABR article.

Reese once told reporter Scott Ostler in 1985 that every Sunday, Angels manager Frank Chance “gave me a dollar and a baseball” for his work.

Reese’s own PCL playing career started in Oakland in 1924, and three years later he was acquired by the Yankees during their legendary 1927 season. Reese wasn’t called up until 1930, wearing Nos. 25 and 26 over a three-season span.

He ended hitting .346 in 188 at bats in ’30 – third best average on the team behind Lou Gehrig and Ruth. Reese was actually the second Jewish player in Yankees history after Phil Cooney, a third baseman who played exactly one game for the 1905 New York Highlanders.

The PCL’s Angels, a farm team for the Chicago Cubs, got Reese back in 1933. Missing missing most of that season with injuries and illness, Reese still hit .330 in 104 games. He followed that up in ’34 hitting .311 with 12 triples and the best fielding percentage of all PCL second basemen.

As another story goes, during an Angels exhibition game involving celebrities, songwriter Harry Ruby was relaying pitches to his Jewish catcher Ike Danning by speaking Yiddish instead of using signs. But when Reese came to the plate, he understood it. He went 4-for-4. After the game, Ruby asked Reese how he did so well against him. That was when Jimmie told Ruby his real name.

Two more years with the Angels followed two more years with the San Diego Padres, the Boston Red Sox minor-league affiliate, and then Reese all-but retired as a player after the 1938 season. He stayed active for two seasons with teams in the Western International League and then managed baseball teams as he served in the Army from November 1942 to July 1943 with the 12th Armored Division at Fort Campbell, Kentucky.

After the war, Reese signed on as a scout for the Boston Braves, then was a coach back in San Diego before he was appointed manager in 1960. But Reese wasn’t happy doing that job and left in ’61 halfway through the season.

“I’m best suited as a liaison man, as a coach,” Reese would say. “I just am not suited to give a guy hell.”

More time coaching in the minor leagues included stints with the Seattle Angels, a Triple-A team that would help the city prepare for the arrival of the 1969 American League Seattle Pilots, and more scouting for the newly created Montreal Expos.

In 1972, he approached some people he knew with the California Angels to see if they had any openings. The best they could do was bring him in as a conditioning coach under manager Del Rice.

Reese, never married and with no children, was attached 100 percent to baseball as a master of the fungo bat, at the ballpark early and often. When the Angels acquired pitcher Nolan Ryan from the New York Mets, Reese became something of a mentor. Eventually, Ryan named one of his sons Reese after him.

“We became really close friends,” said Ryan. “He definitely had an influence on me, and I thought he represented what to look for in a lot of people. I wanted to honor him in that way. I thought if Reese could grow up to be the person Jimmie Reese was, it’d be quite a thing. He was a caring person who was available to help anyone who sought help. He was an honest person, very low-key and had a lot of nice qualities.”

After serving under Del Rice, Reese coached for 10 more Angels’ managers — Bobby Winkles, Norm Sherry, Dave Garcia, Jim Fregosi, Gene Mauch, John McNamara, Cookie Rojas, Doug Radar, Buck Rogers and John Wathan.

Sherry recalled how “everybody liked the man. He was a great worker. When I was the pitching coach and I’d want my pitchers to run, he’d hit these fly balls to make them run after. He’d make it so they’d almost catch ’em; they’d have to get a good run in to catch the ball. That was the last 20 minutes of batting practice.”

In 1984, Reese suffered a heart attack and stopped traveling with the team. In ’85, he was asked about how the game had change — or, really had not.

“It’s still the same game, from Babe Ruth to Reggie Jackson,” said Reese. “Baseball is baseball.”

The Angels had a day to honor him in 1989 and his No. 50 was retired. He was also inducted into the Pacific Coast League Hall of Fame in 2003, celebrating the league’s 100th season. The Hall was created in 1942 by the Helms Athletic Foundation of Los Angeles.

When he passed away in the summer of 1994, at age 92, it was a month before an MLB work stoppage that would eventually cancel the season. “We all suffered it,” said Angels manager Joe Maddon of that time period. “He was the youngest 92-year-old I’d ever met.”

Reese was said he was the oldest person to have regularly worn a uniform in the history of organized baseball. All of that with the wisdom of Solomon.

“In a world that lacks gentlemen, he was one,” said Maddon, who also coached with Reese. “He’d check in daily, look you right in the eyeballs when he spoke to you — he had this 1930s way of talking. Jimmie was loved by everybody.”

Maddon recalled how Reese “made me feel like a million bucks when I wasn’t worth anything” as a scout or coach in the Angels’ system. “Oftentimes, he’d put a hand on my shoulder, and he’d have tobacco juice dripping down the sides of his mouth, a couple-day beard growth, holding his fungo. He’d get real close with those steel blue eyes, and he’d tell me, ‘You’re the master. You’re going to be a big league manager someday.’ ”

Angels owner Gene Autry said in the Los Angeles Times 1994 obituary: ““I was very fond of Jimmie Reese. He’s one of the finest men I’ve ever known. We will miss him, I’ll tell you that. He was a wonderful, wonderful man.”

Who else wore No. 50 in SoCal sports history?

Make a case for:

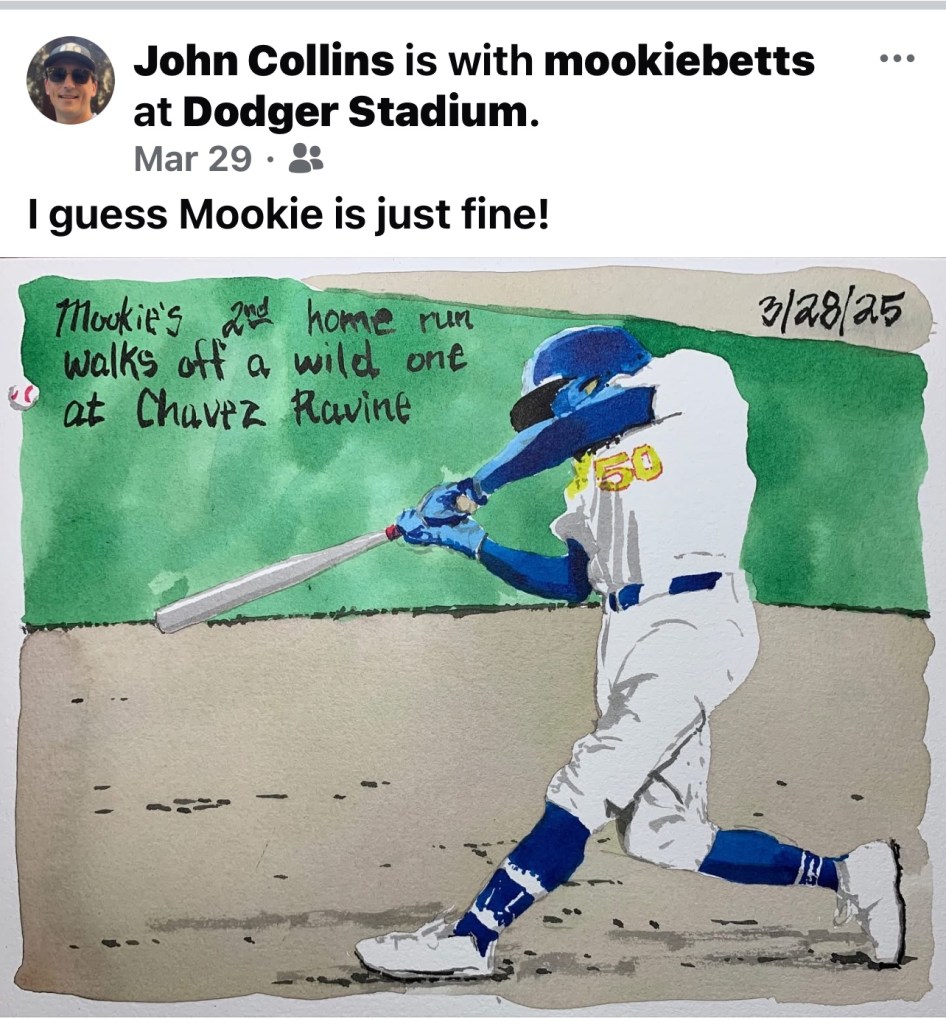

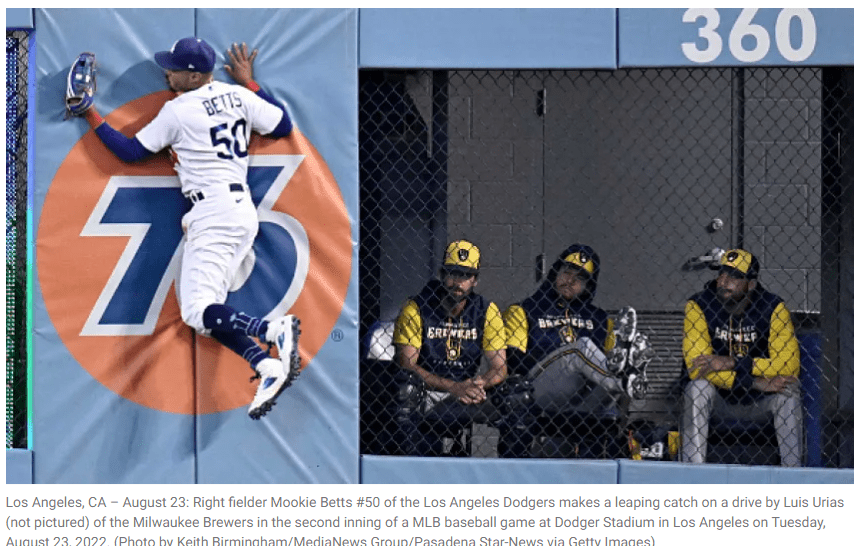

Mookie Betts: Los Angeles Dodgers outfielder (2020 to present):

Moving along on the red carpet prior to the 2024 Golden Globe Awards in Beverly Hills, Mookie Betts was networking. The seven-time All Star, winner of a Most Valuable Player trophy, a Gold Glove and Silver Slugger, and four years into his multi-year contract that lends us to believe he will be a Los Angeles Dodgers right fielder-second baseman through 2032, also has a company called One Media/Marketing Group. You sure that isn’t Pharrell Williams?

“This is our first time being out and being able to attend something like this. We watched it on TV so much,” Betts told The Associated Press. In 2022, Betts and Co. made their first major announcement that they had partnered up with Propagate, a Los Angeles-based content creation company led by Emmy and Golden Globe Award-winning entrepreneur Ben Silverman. Later that year, Betts took on the role of executive producer through his OMG company on the documentary film, Jackie Robinson: Get to the Bag. “I’m an athlete in this same space like he was, and I want to be known as more than an athlete,” Betts told TheWrap. “I don’t want to be just the athlete. I don’t want to be in just this little box. I know I’m more than that. Yes, I may be good at hitting the baseball, but I’m also good at being an entrepreneur and running companies and doing these things with my best friends.”

At the Beverly Hilton, Betts was betting on himself. The question finally came: What are you wearing? He hesitated, struggling to describe his black suit with a black bow tie, a silver lapel pin and a black brimmed hat. “I’m wearing confidence,” he said.

Confidence came, the story goes, when Betts debuted with the Boston Red Sox in June of 2014 and they gave him No. 50 because, well, it was available, and some weren’t sure the 5-foot-9 and 180-pounder from Nashville, Tenn., would stick around. Going into his second season, as veteran players dropped off the roster via trade or free agency this winter, Red Sox home clubhouse manager Tom McLaughlin contacted Betts to ask if he wanted a “better number.”

“A lot of my friends back home got jerseys with my number. I didn’t want them to have to get new ones,” Betts told the Boston Globe. “Nobody wants 50, I knew I would be able to keep it.”

He made the AL All Star team in his third season, then won the AL MVP in 2018 while leading the league in batting average, slugging percentage and runs scored for the World Champion squad.

The Dodgers traded for Betts in February 2020 and signed him to a 12-year contract extension worth $365 million. Since then he’s been part of the Dodgers’ 2020 World Series team and was second in the 2023 NL MVP voting.

When he joined the Dodgers, he asked them for the same No. 50.

When Betts returned to play against the Red Sox at Fenway Park in 2023, some magical things happened. In his first game there in four years, he received a standing ovation from the Boston fans. He went 1-for-4 with two runs in the Dodgers’ 7-4 win. The next night, Betts went 3 for 6 with an RBI single. But he also committed a run-scoring error while playing second base in the eighth. In the top of the ninth, he made the final out with the bases loaded, flying out to the center field warning track.

“We’re producers not directors,” Betts said of his last out. “Produced a good swing. Can’t direct where it goes.”

The series finale on Sunday, another 7-4 Dodgers win, saw him hit a two-run homer during another three-hit game. That gave him seven hits in the series. It was also his 35th homer of the year, tying a career high. He pumped his arm as he rounded second base, with the Fenway fans mixing applause and chants of “Moooo-kie!”

It was only a couple years earlier when Betts was playing his first game at Dodger Stadium – during the COVID-19 pandemic. No fans. Just cardboard faces taking up seats. No cheers. Middle of July because of the delayed season. And a lot of tension in the air.

Before the game, Betts came onto the field for the National Anthem and took a knee. Teammates Cody Bellenger and Max Muncy stood on either side of Betts, with a hand on his shoulder.

As players wore Black Lives Matter patches and a black ribbon stretched across both foul lines before the anthem played, Betts said he knelled down for change and as a protest of injustices that outraged the country.

“Just unity,” Betts said on what that moment represented. “Everybody’s here, we’re all on the same team. We’re all here for change. We have a great group of guys here. We’re all supportive of each other. It definitely doesn’t surprise me that Belly and Muncy were there with me.”

“I’m proud of him for making that decision,” Dodgers manager Dave Roberts said.

Betts got his first hit of a Dodger later that night, a single to left field in the seventh inning. He asked to keep the ball. He then scored to give the Dodgers a 2-1 lead in a game they would win, 8-1.

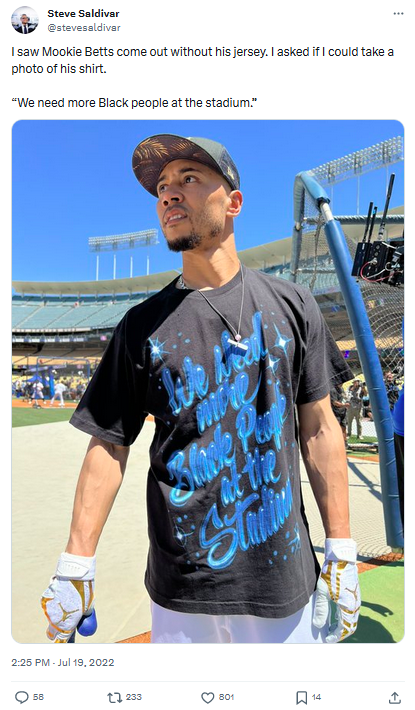

The Washington Post ran a 2024 story titled “Mookie Betts knows he can’t save baseball. He just plays like he can.” The subhead read: “The Dodgers star still wants more people who look like him at the stadium, but he understands all the forces that stand in the way.”

The gist of the story:

Mookie Betts occupies a rare position in the modern professional sports landscape: a Black American baseball superstar. Betts feels a responsibility accompanying his unicorn status, but he also recognizes the forces that make him such a rarity are bigger than he is.

Baseball’s hold on the Black community has loosened over generations, to the point that vanishing representation among Black Americans in the sport has gone from noticeable to concerning.

But while his home runs on uppercut swings and his leaping outfield catches serve as a live-action billboard to anyone who might find inspiration, the Los Angeles Dodgers star doesn’t pretend to overstate his influence.

“I’m not trying to come here and be the savior for baseball or for the culture,” Betts said.

Betts understands the random circumstances that contributed to his being 11 seasons into a career with a Hall of Fame trajectory. He didn’t learn to love baseball until he was getting paid to play it.

In the 2023 book, “Smart, Wrong and Lucky: The Origin Stories of Baseball’s Unexpected Stars,” Betts’ baseball origin story is one of several told by author Jonathan Mayo, which we reviewed. Betts was the 2011 fifth-round pick (No. 172 overall) by the Red Sox out of high school in Nashville, Tenn., tabbed as a shortstop with the design of making him a second baseman. If the Red Sox hadn’t kicked in a $750,000 signing bonus, Betts was ready to go play at the University of Tennessee, a bargaining leverage high school players still have these days. And if the Red Sox hadn’t jump on him at that moment, they feared the San Diego Padres, which also scouted him thoroughly, were ready to pounce.

The Red Sox used “good old-fashion scouting and some new-fangled approaches” to figure out Betts’ worth, Mayo reports. Red Sox area scout Danny Watkins was the point person. As he knew the bigger names were at nearby Vanderbilt University – 12 were taken in that 2011 draft — he still was able to travel to see Betts in high school, sit with him, talk to his parents, cultivate a relationship. Also confirming Watkins’ reports was Tom Allison, a cross checker who in 2021 joined the Dodgers as a special assignment scout.

Watkins found more info about Betts’ athletic abilities watching him play high school basketball, more a sense of his competitiveness and athleticism. Although Watkins projected Betts as a middle infielder, he strategically slotted him as a shortstop – an important position – to convey why Betts was worthy of assessment. Also, the Red Sox already had a solid second baseman in Dustin Pedroia, so Betts would need to crack the lineup elsewhere.

Watkins also had a new analytic tool to try out on Betts: NeuroScouting, a company that simulated decision-making reaction time, was just starting out and Watkins had Betts try the test – when you see the ball on the screen, hit the space bar. If you see the seams going one way, tap it again. Betts tested very well, but the Red Sox didn’t know how to factor it into their assessment with a lack of historical data.

How Betts went all the way to the fifth round is the other part of the puzzle that isn’t always easy to assess in the moment as names flash by and voices are heard. The Red Sox actually had four of the first 40 picks – and still waited on Betts as the scouting director Amiel Sawdaye had the final call. Cal State Fullerton pitcher Noe Ramirez had enamored a few Red Sox scouts, so he was taken in the fourth round. But the Red Sox were now worried the Kansas City Royals would take Betts early in the fifth round. They did pick a high school shortstop – Patrick Leonard, who never made it to the big leagues. Sixteen picks later, Boston took Betts.

More notes on Betts:

== In the 2023 World Baseball Classic, Betts wore No. 3. That was his high school basketball number. Betts has said that Allen Iverson, the NBA legend, had a huge impact on him. But what’s also the truth: Betts also couldn’t get No. 50 in the WBC because U.S. teammate and veteran pitcher Adam Wainwright secured it, based on seniority.

== It has been reported that Betts was the nephew of Terry Shumpert, who played 14 seasons in the big leagues, but they are actually first cousins once removed. Shumpert is the first cousin to Betts’ mother, Diana. Shumpert, who played for the Triple-A Nashville Sounds in 2004, got to work with Betts in his development. There is no dispute that Shumpert is a distant cousin to Meghan, Duchess of Sussex. So does that make Betts part of some royal lineage as well? He was also born Markus Lynn Betts in 1992, and it was said his parents picked that name so his initials would be MLB. Mookie became his nickname was his parents were fan of former NBA guard Mookie Blaylock.

== Betts enjoys swapping uniforms with other players – a tradition made popular in European soccer. “All for the culture,” Betts told The Athletic recently. “I’ve been telling you, I was trying to bring culture and brings stuff to the game. This is just part of it.”

== During the 2023 NL Division Series when the Dodgers faced the Arizona Diamondbacks, Betts interrupted manager Torey Louvello’s press conference by coming in for a hug. “He raised me in this game,” Betts said about Louvello. Louvello returned the love. “That’s what makes you feel good when you’re a teacher and kind of a mentor,” said Louvello, who had been a Boston Red Sox coach from 2013 to 2016, overlapping with Betts’ time there. “You have a young athlete, you know what he’s like in the minor leagues, he gets to the big league level, and you have hours and hours of conversations about what it will be like when get to that level of greatness. For me, I watch him perform and there’s nothing better. … that’s a beautiful human being.”

== When Betts formed The 50/50 Foundation, it came from the idea, according to the website, that: “Growing up his parents instilled in him the desire to give back and support charities. In his free time, Mookie is an avid bowler and wanted to use his favorite hobby as a way to give back. In 2023 came the first Mookie Betts and Friends Bowling Tournament to raise funds for his foundation. “He believes in breaking the barriers that hold kids back from their potential to make a bigger difference in this world,” the site says. It focuses on mental/emotional health, nutrition, financial literacy and physical fitness for young people. It has resulted in AAU Team Mookie, Betts on Us Fund and other programs supported by him and his wife, Brianna.

== What’s also been floated: Betts first athletic love has always been bowling. He considered becoming a professional. At the 2023 PBA U.S. Open championship in Indianapolis, Betts was one of the 108 entrants, receiving an exemption into the main draw via the U.S. Bowling Congress. At the end of his first eight-game qualifying set, Betts was tied for 19th in his group with the No. 1 bowler in the world, Jason Belmonte. Betts has bowled three officially three officially sanction perfect 300 games, the last in 2017.

== Betts is now into pickleball. He had a custom court built on the lawn of his home in Encino and it allowed him to do something as he was healing from a broken hand in June, 2024. Betts was quickly able to replace one obsession — learning shortstop, arguably his sport’s most difficult position, on the fly — with another: pelting plastic balls with 16-inch paddles. “I’m the type of person who can’t just sit down,” Betts said. “I don’t operate that way.”

Len Ford, Los Angeles Dons offensive end (1948 to 1949):

The All-American Football League team that arrived in L.A. just ahead of the Rams’ move from Cleveland would have only one player eventually inducted into the Pro Football Hall of Fame in Canton, Ohio. It was Ford, the 6-foot-5, 245-pound University of Michigan standout, passed over by every NFL team in the 1948 draft — it was a time the league was still hesitant about drafting African American players. So he signed with the upstart league in L.A. He was excellent on defense and a favorite on offense with leaping, one-hand grabs that netted 67 receptions and eight TDs with more than 1,000 yards in two years covering 26 games. After the AAFC dissolved in 1949, Ford switched to defensive end and played eight seasons for the Cleveland Browns (wearing No. 53 and No. 80) and established himself on teams that went to the NFL championship game seven times, winning three, and playing in four Pro Bowls. He was also named to the Hall of Fame’s All-1950s Decade team.

Dave Dalby, UCLA football center (1969 to 1971); Los Angeles Raiders center (1982 to 1985):

Elected to the UCLA Athletic Hall of Fame in 1999, his bio stats that the two-time All-Conference player could be “the greatest center in UCLA football history.” He started 31 straight games for the Bruins and was the team MVP in ’71. Drafted by Oakland in 1972, he made the move with the Raiders to L.A. and started 135 of his 205 games played, with one Pro Bowl appearance and three Super Bowls. He snapped it to, over his career, Daryle Lamonica, Ken Stabler, Mike Rae, Jim Plunkett, Dan Pastorini and Marc Wilson.

Ken Iman, Los Angeles Rams center (1965 to 1974):

He started every game in that stretch – 140 in a row. From Bill Munson to Roman Gabriel to Pete Beathard to John Hadl and James Harris.

Adrian Young, USC football linebacker (1965 to 1967): A native of Dublin, Ireland, the Bishop Amat High standout came to USC as a fullback. His moment in the spotlight game in the ’67 USC-Notre Dame game when, as the Trojans’ team captain, he intercepted four passes and had 12 tackles in a 24-7 win. He was a 2012 inductee into the USC Hall of Fame.

Jay Howell, Los Angeles Dodgers relief pitcher (1988 to 1992): Registering 85 saves and winning 22 games. And an ’89 All Star selection. Just check the glove for pine tar if needed.

Nathan Eovaldi, Los Angeles Dodgers pitcher (2011 to 2012): Had a 1-6 mark and a 4.14 ERA after 10 games in ’12 before he was traded to Miami in the package for Hanley Ramirez. Then became a two-time AL All Star in his age 31 and 33 seasons. Helped the Red Sox outst the Dodgers in the 2018 World Series.

Have you heard this story:

Orson Villalobos, Compton College football defensive end/linebacker/special teams (2025):

Villalobos, a 50-year-old from Compton who runs a grill cleaning business, according to his Instagram account, and also works in the Compton College financial aid office, was ready, willing and eligible to put on a jersey and helmet and play for the school during the 2025 season. He also wore his age on his chest, his back and his sleeves. He told KABC-Channel 7 that it was his 9-year-old son, Orson II, who inspired him to give it a shot during a time he was back at Compton college to study kinesiology as he wanted to pursue work on coaching. Villalobos, listed at 6-feet and 200 pounds out of Lynwood High more than 30 years earlier, made 10 tackles during the team’s 0-8 start to the season, but then the Coyotes had to forfeit the last two to end its agony. “We didn’t have enough players to finish the season,” Villalobos told his TikTok fans in late October.

Compton had been outscored, 480-12, including enduring losses of 70-0 at San Bernardino Valley, 64-0 at Grossmont, 63-0 at West L.A., 62-0 vs. Glendale and 56-0 vs. Santa Monica. Their last two games ended with a 64-6 loss vs. Desert and 48-6 at L.A. Southwest. That Compton team also included 45-year-old receiver Lamar Willis (No. 19, out of Bellflower High in Compton), as well as his son, Josiah Willis, a defensive back (No. 20, out of Cerritos High in Compton). A post on Willis is included in the No. 19 recap of this series. Compton College hasn’t won a game since the fall of 2022.

Sid Fernandez, Los Angeles Dodgers pitcher (1983):

The Hawaii native drafted by the Dodgers out of Kaiser High in Honolulu was said to have picked this number because it represented the 50th state of the union. He took it with him through a 15-year career (114 wins) to the New York Mets, Baltimore, Philadelphia and Houston after his one rookie season with the Dodgers in ’83 (0-1 in two games, six innings).

More local pride:

Ed Guiterrez, USC linebacker (1976 to 1977): Hanging in the foyer of the campus gym at Bishop Mora Salesian High School in Boyle Heights is this display honoring Guiterrez (Class of ’73), who went on to play at East L.A. College (All State in ’74 and ’75) before going to USC to play for coach John Robinson as the “little guy who made good” for the 11-1 team in ’76 and 8-4 team of ’77. Too bad this photo below couldn’t have been added to the display:

We also have:

Jack Hamilton, Los Angeles Angels pitcher (1967): He went 9-6 with a 3.24 ERA in 26 games after a trade from the New York Mets. Then he switched to No. 24.

Sam Clancy, USC basketball center (1998-99 to 2001-02)

Dan Gadzuric, UCLA basketball center (1998-99 to 2001-02)

And for good measure:

The Dodgers float entered in the 2008 Tournament of Roses Parade to mark their 50th year in Los Angeles (with Vin Scully perched on it, and Roger Owens walking next to it pitching peanuts):

Anyone else worth nominating?

Let’s add Adrian Young, a standout USC linebacker in the mid-sixties.

LikeLike