This is the latest post for an ongoing media project — SoCal Sports History 101: The Prime Numbers from 00 to 99 that Uniformly, Uniquely and Unapologetically Reveal The Narrative of Our Region’s Athletic Heritage. Pick a number and highlight an athlete — person, place or thing — most obviously connected to it by fame and fortune, someone who isn’t so obvious, and then take a deeper dive into the most interesting story tied to it. It’s a combination of star power, achievement, longevity, notoriety, and, above all, what makes that athlete so Southern California. Quirkiness and notoriety factor in. And it should open itself to more discussion and debate — which is what sports is best at doing.

The most obvious choices for No. 25:

= Gail Goodrich: UCLA basketball and Los Angeles Lakers

= Tommy John: Los Angeles Dodgers

= Jim Abbott: California Angels

= Troy Glaus: UCLA baseball and Anaheim Angels

= Norm Van Brocklin: Los Angeles Rams

The not-so-obvious choices for No. 25:

= Rafer Johnson: UCLA basketball

= Paul Westphal: USC basketball

= JK McKay: USC football

= Frank Howard: Los Angeles Dodgers

The most interesting story for No. 25:

Tommy John: Los Angeles Dodgers pitcher (1972-74, 1976-78), California Angels pitcher (1982 to 1985)

Southern California map pinpoints:

Inglewood (The Kerlan-Jobe Orthopaedic Clinic at Centinela Hospital, known today as the Cedars Sinai Kerlan-Jobe Institute in Santa Monica); Downey (Rancho Los Amigos Hospital); Los Angeles (Dodger Stadium), Anaheim (Angels Stadium)

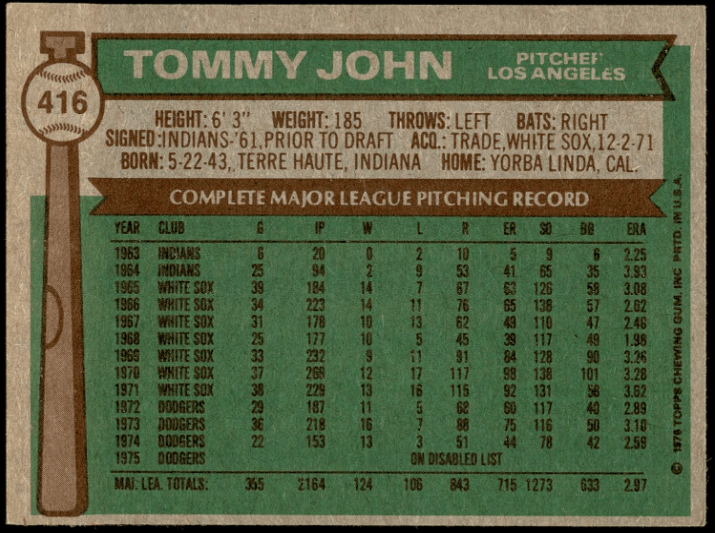

The statistical snapshot of Tommy John’s career on the Baseball Reference website shows 26 years as a Major League Baseball pitcher. It starts at age 20 in Cleveland in 1963. It goes to age 46 in New York in 1989.

The data is somewhat neatly split into two distinct hemispheres.

The first 12 seasons include his first three years in Los Angeles with the Dodgers. The last 14 start with three more LAD seasons as well as turning as a California Angel. The highlighted notation that divides the two parts in 1975 reads: “Did not play in major or minor leagues (Eponymous Surgical Procedure).”

If something is eponymous, it means that a person, place or thing is named after someone. Tommy John Surgery, when compared to the Donner Pass or the Washington Monument, may be far more ubiquitous to anyone who really focuses on how it is eponymous.

There is an official entry (along with the phonetics) in the Merriam-Webster dictionary:

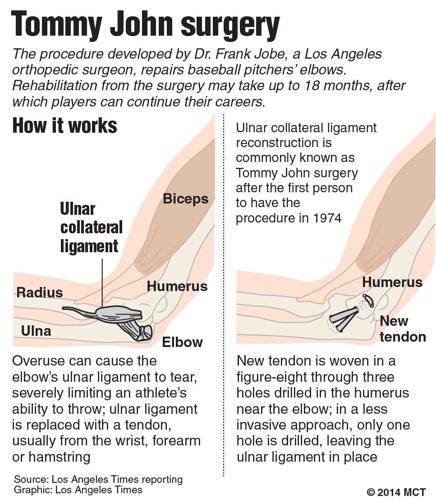

The integrity of the Ulnar Collateral Ligament — aka, UCL — is often defined in MLB history as before or after Tommy John was connected to it. Someone had to be first, trusting a doctor creative and brave enough to try something. What did Tommy John have to lose?

The story

Tommy John took the mound at Dodger Stadium on July 17, 1974 with a 13-3 record, best in the National League, along with three shutouts, five complete games and a 2.59 ERA. The All-Star break was coming up, and he was a lock to make the National League team going to Pittsburgh with teammates Ron Cey, Steve Garvey, Jimmy Wynn, Mike Marshall and Andy Messersmith.

Then Tommy John broke.

The first two Montreal Expos hitters that the Dodgers’ left-hander faced on that cool Wednesday night game started the third inning with a single and a walk.

On John’s first pitch to the next hitter, Hal Breeden, something didn’t feel right. The second pitch made him feel worse.

“I can describe the pitch vividly,” John would say years later. “I threw the pitch, and heard this banging sound in my elbow and felt this sharp pain.”

John walked off the mound with a 4-0 lead and no idea where to go. Geoff Zahn came in to strike out Breeden, but the inning deteriorated after that. The Retrosheet.org documentation of the game reads:

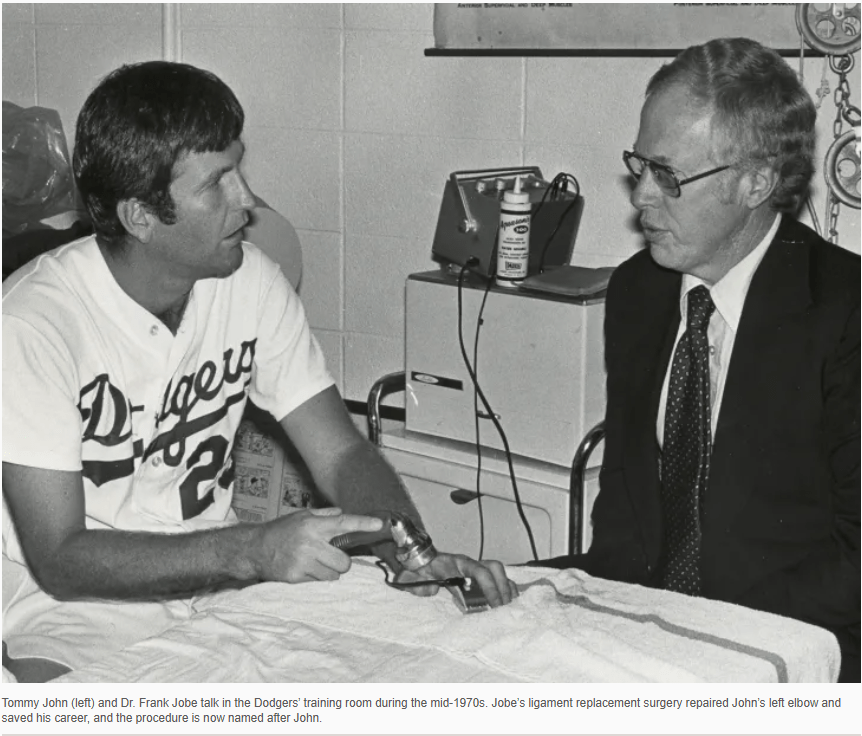

Dr. Frank Jobe showed up within minutes in the Dodgers’ clubhouse to consult with John. His initial diagnosis was a torn ligament. A second doctor agreed after looking at a state-of-the-art X-ray — long before the diagnostic tools of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or computerized tomography (CT) were available.

This was a time when arm surgery was the only way to know for certain whether the ligament was just strained or pulled completely off the bone.

John’s trust in Jobe and his team went back to the end of the 1972 season, when John jammed his left elbow into the ground sliding into home, dislodging bone chips. Five days later, Jobe and Kerlan removed the fragments, which shut him down for the last month.

In this case, Jobe thought it best that John rest a couple of weeks, start back slowly and see if the arm improved. John did try that. But he couldn’t throw.

Because of the work Jobe had been doing with polio patients as Rancho Los Amigos Hospital in Downey, he knew of the work of Dr. Herb Stark, who repaired hands by grafting tendons from elsewhere in the body.

Somewhere out of left field, Jobe work-shopped an idea at his Orthopedic Clinic in Santa Monica as John sat and listened about a a way to try that grafting with the elbow. No one knew how it would go, especially with an athlete. At best, Jobe gave John a one-in-100 chance of it working.

“He said, ‘Well, if I don’t do anything, I’ve got zero chance’,” Jobe told the MLB.com in 2013. “And then he came in about a week later and said, ‘Let’s do it,’ and those words pretty much changed sports medicine.”

John added: “If he would have told me to go stand naked at Dodger Stadium, that it would heal my arm, I would have done it. It would have made everybody laugh, but … I believed in Frank Jobe.”

On September 25, Jobe and several colleagues opened up John’s left elbow and saw the ligament torn. Within a four-hour procedure, Jobe removed about six inches of tendon from John’s right arm, drilled holes into his left elbow, threaded the tendon in a figure-eight pattern, anchored it tight, and sewed up the incision.

And probably said a small prayer.

It took a year and nine months later before John was ready to try it out on a big-league mound. In an April 1976 game in Atlanta, with only some 15,000 fans in attendance, John was the Dodgers’ starter. He went the first five innings, faced 24 batters, gave up a three-run homer to Darrell Evans in the fifth, and took the loss in a 3-1 decision.

But, in reality, it was a major victory.

Tommy John Surgery, which didn’t even have that name yet, had been put into the sports universe. It would be another four years before Jobe tried it again on another pitcher, waiting to see how John’s results took hold before adding new layers to the procedure.

In a 2020 story posted in The Athletic, John’s surgery story was named No. 12 in the series of the 40-greatest comebacks in sports history. The rest of the Baseball Reference may also explain more matter of fact.

The 14 additional years John pitched from age 33 to 46 included three 20-win seasons, two second-place finishes in the Cy Young voting, and three All Star games. He exceeded 200 innings in a season seven times after 1976, compared to five 200-inning seasons prior to the surgery.

With 288 wins, a 61.6 career WAR, and more than 4,700 innings in 700 starts, John was just shy of the considered “shoo-in” Hall of Fame categories. He had 188 no-decisions in his career. If he only got a fourth of them go to his way, he is beyond that magical 300-win threshold.

In 14 post-season appearances, John also posted a 6-3 record and 2.65 ERA.

His career included a time wearing No. 25 for the California Angels — half of ’82, all of ’83 and ’84, and half of ’85. John went went 1-1 against Milwaukee in the ’82 ALCS. He pitched for the Yankees against the Dodgers three times (two starts) in the 1981 World Series.

More statistical measurements put John’s career in a comparable company with Hall of Famers like Jim Kaat, Bert Blyleven or Tom Glavin.

Until then, John and Jobe are charter members of the UCL Hall of Fame. And Tommy John has the naming rights.

The co-conspirator

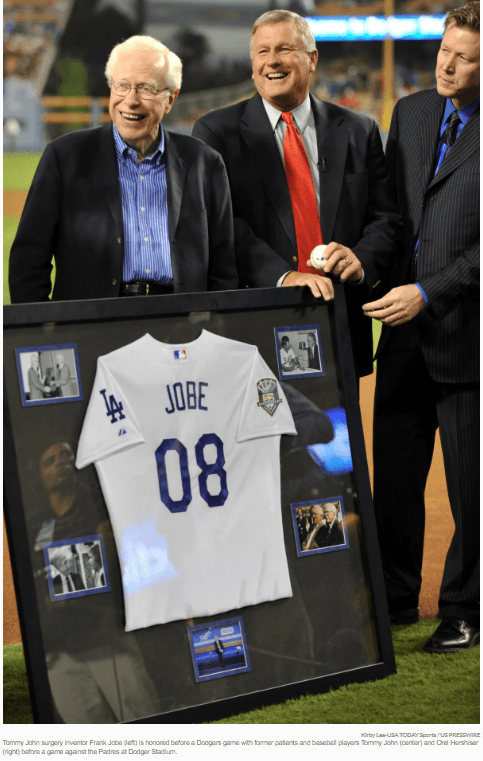

Dr. Frank Jobe, after spending some intense time for the U.S. Army in World War II, graduated from La Sierra College in Riverside in 1949 and went on to medical school at nearby Loma Linda University. He completied clinical studies at White Memorial Hospital and Los Angeles County Hospital, and received his M.D. degree in 1956. He developed an interest in orthopedics, and continued his training in a three-year residency at the USC.

His relationship with the Dodgers started in 1964, and his first surgeries that year included removing a bone chip from Dodgers pitcher Johnny Podres. He and Dr. Robert Kerlan, one of his medical teachers, founded the Kerlan-Jobe Orthopedic Clinic in ’65.

One of their first major projects was trying to preserve the career of Sandy Koufax, battling an arthritic left elbow.

“Sandy Koufax teases me, or did one time,” Jobe said once. “He said, ‘Why weren’t you smart enough to come up with that 10 years before and I think it could be called the Koufax operation?’”

Koufax’s career ended at age 30 due to an elbow issues, and Jobe said he believed later he could have tried UCL surgery.

Jobe’s official capacity on the Dodgers’ medical staff went from 1968 until 2008. His second most famous Dodger surgery was reconstructing the right shoulder of Orel Hershiser in 1990 with another new procedure to repair cartilage damage and tighten the ligaments.

“If the Tommy John procedure remains the Mona Lisa of sports surgeries,” as Times sportswriter Chris Dufresne once declared, “then Jobe’s landmark 1990 operation to rebuild the right shoulder of then-Dodger Orel Hershiser could be enshrined down the hall in the Louvre.” The phrase was in Jobe’s Los Angeles Times obituary.

Jobe died in March of 2014, less than a year after he was recognized for his work by the Baseball Hall of Fame induction weekend of 2013. Many still campaign for Jobe to receive his own official Cooperstown plaque. John remained eligible with the Baseball Writers’ vote until 2009, but he never received more than 31.7 percent of the 75 percent required for election. Five times, John has been on a veterans’ committees revote. In 2024, he received seven of 16 votes but needed 12.

“Twenty-six years, 288 wins and [an MLB-record] 188 no decisions,” John said when asked how the committee should value career longevity. “Your arm was in good shape, and you must be doing something right or you wouldn’t be going out there every five days. If I had a say, I would vote me in. But I don’t.”

The legacy

A March, 2024 story for the Associated Press by Jay Cohen starts: There is a bridge that runs from Tommy John and Dr. Frank Jobe in 1974, all the way to Shohei Ohtani, Justin Verlander and Bryce Harper. A thread that connects an increasing number of baseball’s biggest stars. Mostly on the mound, but at the plate, too. An operation that changed everything.

According to a Google doc sheet called the Tommy John Surgery List, which is about as accurate as any data base has been in this field, more than 2,400 players have had the elbow surgery after Tommy John was Patient Zero.

Some who have surgery after him aren’t included on this list because of a slightly different procedure done. It’s all the same, basically.

A 2016 book called “The Arm: Inside the Billion-Dollar Mystery of the Most Valuable Commodity in Sports,” author Jeff Passan begins quite graphically with a play-by-play of a four-hour surgery by Dr. Neal ElAttrache as he scrambles to repair the right elbow of one-time Dodgers pitcher Todd Coffey.

During the procedure, Passan writes about how ElAttrache cut open Coffey’s legs and started digging round for a usable tendon, “like MacGyver.” He ended up using a cadaver tendon that was shipped in.

If a pitcher on any level — high school, college, professional — could see a documentary of what goes on during one of these operations, would they think twice about having it done to them?

“One thing I know about athletes: No matter how awful or off-putting something is, if they think it will heal them or help them improve, they’ll do it,” Passan told us. “Much as I’d love to see a black-and-white ‘Tommy John Madness’ film in widescreen, there’s no such thing as ‘Scared Straight’ in sports.”

Why do so many pitchers have this surgery, and why does it feel far too normalized? There are many hypothesis to whether it has reached epidemic proportions. Key moments in time are noted. Modest proposals are offered to stem the tide.

But no matter the discussion, Tommy John’s name elbows everyone else out of the way for the starting point.

Circling back to Passan’s book, I asked him: You got to talk to both Tommy John and Dr. Frank Jobe and you seem to admire the fact they were both in this together. They knew it was kind of the blind leading the blind, so why not try it?

“I marvel at Frank Jobe’s courage,” said Passan. “I know there had been facsimiles of the surgery on other parts of the body, but when he cut open Tommy John’s elbow, he was doing something no doctor ever had attempted. It takes some kind of self-assurance to pioneer a procedure. Tommy’s approach was as much about self-preservation as it was innovation. He never set out to have his name intertwined with something so ubiquitous. He just wanted to throw because retirement sounded like a bummer.”

In a first-person story for AARP magazine in 2018, Tommy John wanted it known he doesn’t want anyone thinking a surgery named after him is something he tends to endorse.

“It doesn’t bother me to watch my legacy being upstaged by an operation that has saved plenty of ballplayers’ careers,” said John, who in 2021 endured a hospitalization for COVID recovery, a year after he was included in the Modern Era Baseball Hall of Fame ballot but was not selected.

“What does bother me is that my name is now attached to something that affects more children than pro athletes. I was in my 30s and playing major league ball for nearly a dozen years before needing the operation. Today, 57 percent of all Tommy John surgeries are done on kids between 15 and 19 years old. One in seven of those kids will never fully recover.”

If it seems strange to hear Tommy John refer to himself in the third person, especially as it relates to his legacy, take it on a case by case basis.

Who else wore No. 25 in SoCal sports history?

Make a case for:

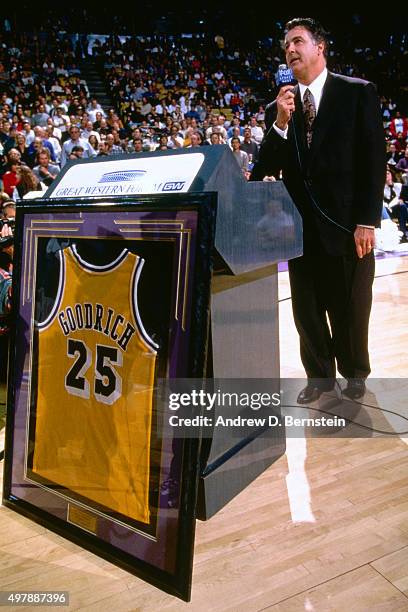

Gail Goodrich, UCLA guard (1962-63 to 1964-65), Los Angeles Lakers guard (1970-71 to 1975-76):

Best known: His number went up on the Lakers’ wall of fame because of his National Basketball Hall of Fame status, predicated on a) being a vital part of the starting quartet of the Lakers’ 1972 title team, along with four All-Star seasons and b) the two NCAA titles he achieved at UCLA, which were the first two for coach John Wooden. Add in that Goodrich was one of the most coveted high school players when he was at Poly High in Sun Valley and led them to the 1961 L.A. City championship, scoring 29 points in the title game despite breaking his ankle in the third quarter.

Goodrich, who set a national record 42 points when UCLA beat favored Michigan in the 1965 championship, was the Bruins’ program all-time scorer when he left. UCLA went 78-11 during his career, including 30-0 in the ’64 title season.

Goodrich’s arrival with the Lakers as the No. 10 overall (and territorial) draft pick led to him wearing No. 11 as a 22-year-old from 1965-66 to 1967-68, backing up Jerry West, Walt Hazzard and Archie Clark. Of all the players picked in that 1965 draft, Goodrich had more NBA seasons (14), games (1,031), points (19,181) and assists (4,805). With the Lakers, teammate Elgin Baylor decided to call him “Stumpy,” because of the short legs on his 6-foot-1 frame. Goodrich lasted three years before he was wrangled away by the expansion Phoenix Suns, who made him a starter and All-Star. The Lakers reclaimed Goodrich after the 1970 season in a deal for Mel Counts, and Goodrich was teamed with West as the new fulltime backcourt.

Goodrich was the team’s leading scorer and fifth in the league when he averaged a career-best 25.9 points a game on a Lakers’ team that ran off the 33-game win streak and an NBA-best 69-13 record. Goodrich also led the Lakers in scoring during their five-game NBA Finals series against New York at 25.6 per game. His 2,145 points in the regular season was fourth in the NBA. In ’73-’74, Goodrich was first-team All-NBA, averaging 25.3 points a game (fourth in the league), leading the league with 508 free throws (in 588 attempts).

Not well known: Goodrich wanted to go to USC, where his dad, Gail Sr., was the captain of the 1939 team and an All-West Coast player. But Coach John Wooden wooed him.

And an important asterisk to Goodrich ending his run with Lakers came after he signed with the New Orleans Jazz as a free agent after the 1976 season — three years, $1.4 million, teaming up with Pete Maravich. For compensation, the Jazz gave the Lakers its No. 1 draft pick for 1979, then finished with the worst record in the league. The Lakers took that pick, won a coin flip with Chicago, and were able to draft Magic Johnson. You’re welcome.

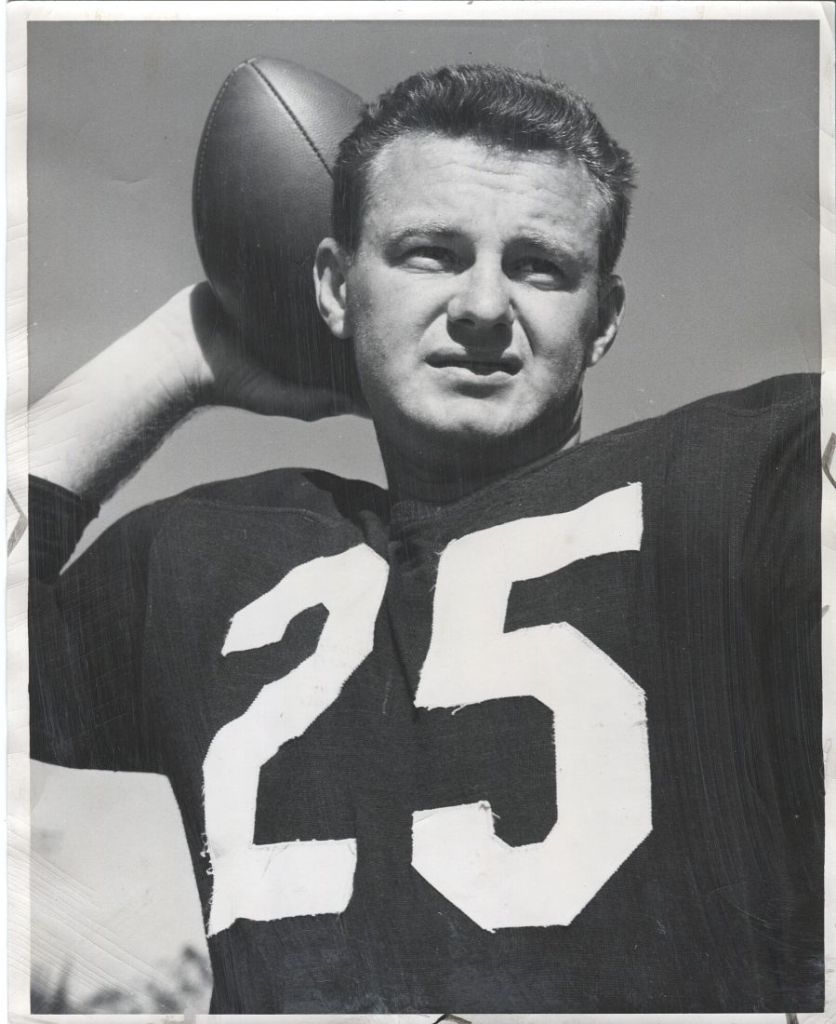

Norm Van Brocklin, Los Angeles Rams quarterback (1949 to 1957):

Best known: On the opening day of the 1951 season, Van Brocklin threw for an NFL-record 554 yards and five touchdowns in a 55-14 win over the New York Yankees. He enjoyed wearing No. 25, just as he did as a star at the University of Oregon. Van Brocklin also played the whole game — important to note, since Bob Waterfield was injured so there was none of the regular back-and-forth substituting the two experienced for awhile with the Rams. Even with the increase in passing stats in NFL teams decades later, the single-game yardage record has survived more than 70 years. As Doug Kelly wrote in a 2022 New York Times story: “It’s the N.F.L.’s most confoundingly persistent record.” Van Brocklin only started eight games in his first three seasons, posting a 6-2 record, because that was because he shared time with Waterfield. Both would become Pro Football of Famers. So who was the greatest quarterback in Rams’ history? Van Brocklin was inducted into the Pro Football Hall of Fame in 1971.

Not well remembered: Van Brocklin wore No. 25 his first three seasons with the Rams (1949 to 51), playing in two Pro Bowls. He switched to No. 11 from 1952 to 1957, led the Rams to the 1955 title game (hosted at the L.A. Coliseum), and in 1958, he announced his retirement from pro football after nine seasons, the final year with Philadelphia.

Troy Glaus, UCLA baseball third baseman (1995 to 1997); Anaheim Angels third baseman (2000 t0 2004):

Best known: Born in Tarzana and emerging from Carlsbad High, Troy Glaus’ senior year at UCLA saw him hit .409, set a Pac-10 record in home runs with 34 (eclipsing Mark McGuire’s 32 at USC) and tied for the conference lead with 91 RBI. Those Bruins went to their first College World Series appearance since 1969. As a sophomore, Glaus was picked to the 1996 US Olympic team and helped lead Team USA to a bronze medal, hitting .342 with 15 home runs and 34 RBI during preliminary games and four homers during the Olympics. The Angels drafted him after his junior year with the No. 3 overall choice in 1977. In 2000, he became the first Angel to score 100 runs, drive in 100 and walk 100 times, leading the AL with 47 homers. The 2002 World Series MVP (hitting .385, three homers and eight RBIs in the seven-game series) led Anaheim to its one and only championship, capping a career that included AL All Star appearances in 2000, ’01 and ’03. He was inducted into the UCLA Athletic Hall of Fame in 2007.

Not well known: Glaus wore Nos. 12 and 14 for the Angels from 1988 to 1989 but was able to get the No. 25 he had at UCLA after the Angels traded Jim Edmonds to St. Louis in spring training.

Frank Howard, Los Angeles Dodgers outfielder/first baseman (1958 to 1964):

Best known: The 6-foot-7, 228-pounder was the first of a bushel of Los Angeles Dodgers’ versions of the NL Rookies of the Year winners when, at age 23, he his 23 homers and drove in 77 with a .268 average in 1960. Howard had just brief call-ups in the 1958 and ’59 seasons, but his legend preceeded him. “I only saw Babe Ruth a time or two,” said Dodgers manager Walter Alston, “but I know about the tape measures they get out for some of Mickey Mantle’s homers. This fellow hit ’em as far as Mickey. Farther. I guarantee you he won’t miss.” Writer Joe Posnanski wrote in a 2025 assessment of Howard: “I think there’s an argument that coming into 1960, he was the greatest baseball prospect in the history of the game.” During his first full season at Dodger Stadium in ’62, known as a pitcher’s ballpark, Howard led the Dodgers with 31 home runs and a .562 slugging percentage, fourth in the NL behind Frank Robinson, Hank Aaron and Willie Mays. When the Dodgers clinched the 1963 World Series title at Dodger Stadium with a four-game sweep of the Yankees, the final game saw Howard have the only two Dodgers’ hits to support Sandy Koufax’s complete game — a single in the second inning off New York starter Whitey Ford and a 450-foot homer in the fifth off Ford that landed on the Loge Level. Going back to Game 1 at New York, Howard hit a ball 460 feet to left-center off Ford that ended up recorded as the longest double in the-then 41-year history of Yankee Stadium, landing near the monuments that had been in the field of play in that era. When Gil Hodges became the manager of the Washington Senators, he pushed for his team to acquire Howard, his former Dodgers teammate. That happened in 1965 in a multi-player deal where the Dodgers got pitcher Claude Osteen. Howard led the AL with 44 homers in 1968 and ’70, had a career best of 48 homers in between that in ’69. He hit 123 of his career 382 homers in a Dodger uniform.

Not well known: In Howard’s first big-league game (Sept. 10, ’58) facing future Hall of Famer Robin Roberts, his first hit in his second at-bat was a home run at Connie Mack Stadium that was hit so hard, Phillies center fielder Richie Ashburn said when it bounced off a metal sign above the wall, it sounded like a cannonball blast and he worried the sign would fall on his head.

JK McKay, USC football receiver (1972 to 1974), Southern California Sun receiver (1975 to 1976)

Best known: As the son of legendary USC football head coach John McKay, it was easier for John Kenneth McKay to go by the name “J.K.” The co-MVP of the Trojans’ 1975 Rose Bowl win (with teammate Pat Haden, his former Bishop Amat High c0hort who threw him a 38-yard touchdown pass in the contest) was on two national title teams and inducted into the Rose Bowl Hall of Fame in 1998.

Not well known: McKay was general manager for the one and only season of the XFL’s Los Angeles Xtreme (2001, as it won the league title) before he became Senior Associate Athletic Director at USC in 2010 under head AD Haden.

Jim Edmonds, California and Anaheim Angels center fielder (1993 to 1999):

Best known: Drafted locally out of Diamond Bar High in the ’88 draft, Edmonds made the AL All Star team as a 25 year old when he hit 33 homers with 107 RBIs and a .290 average. He won also Gold Gloves in ’97 — highlighted by the catch above against Kansas City — and again in ’98. Also in ’98, he hit .307 with 184 hits, 42 of them doubles, to go with 25 homers and 91 RBI. The next six Gold Gloves would come with other teams over the next 12 seasons.

Not well remembered: In spring training of 2000, Edmonds was traded to St. Louis in a deal primarily to get pitcher Kent Bottenfield, who had been an 18-game winner and NL All Star in ’99. Also in the deal: Second baseman Adam Kennedy, who became the Angels’ ALCS MVP in 2002. Bottenfeld lasted less than one season with the Angels and went 7-8 in 21 games before he was dealt to Philadelphia at the trade deadline for a new center fielder, Ron Gant.

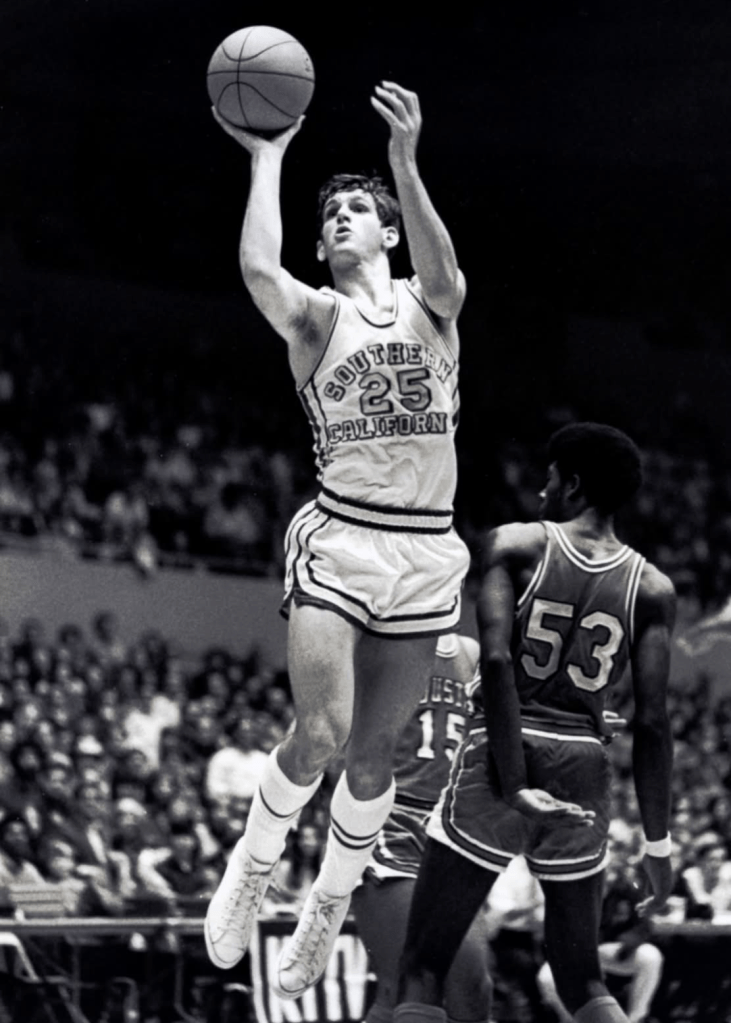

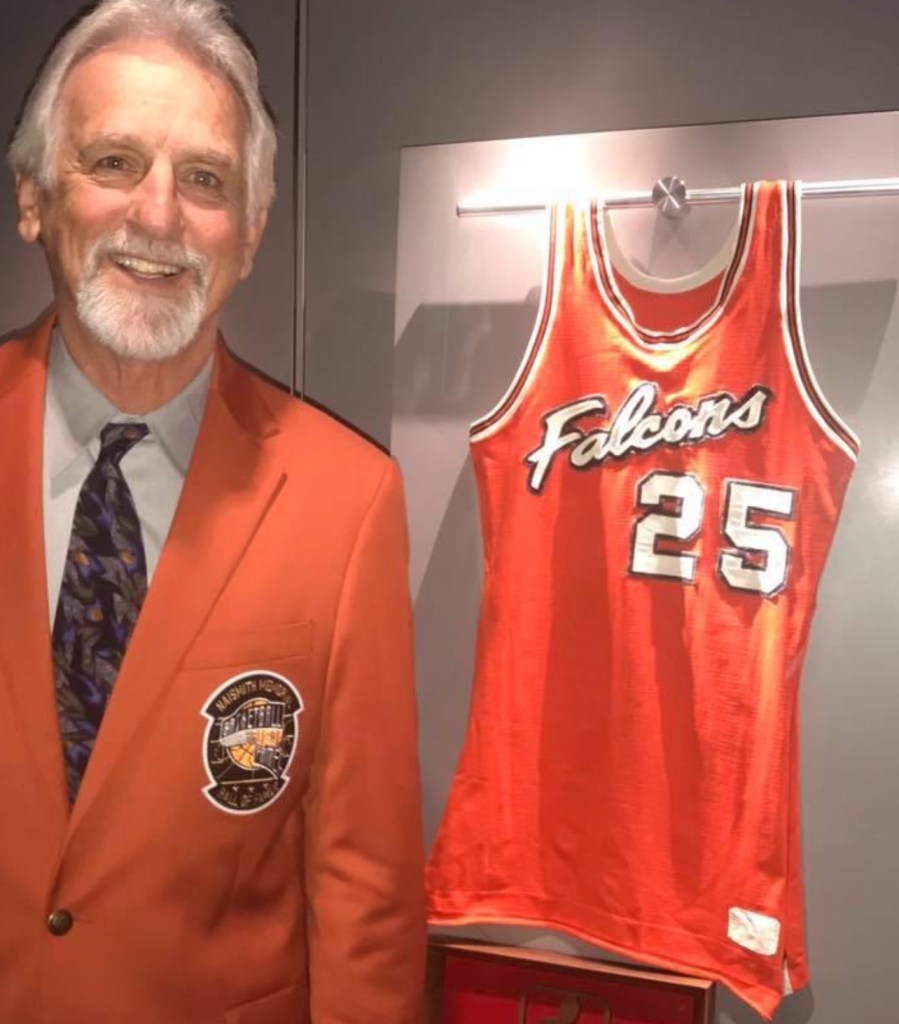

Paul Westphal, USC basketball guard (1969-70 to 1971-72):

Best known: At Aviation High in Redondo Beach, Westphal established himself as a multi-purpose scorer and passer, and USC won out in a recruiting battle with UCLA. Aas a sophomore, Westphal was a key member of the 1971 Trojans team that posted a 24-2 record, the most wins in school history and a still-standing USC mark for best winning percentage (92.3 percent). As a senior, Westphal was All-American first team and team captain as he led the team in scoring with a 20.3 average to go with 5.1 assists a game as a senior. The Trojans started the season ranked No. 3 in the nation (behind No. 1 UCLA) but went 16-10 (9-5 in the Pac-8) including two losses to the Bruins. He averaged 16.9 points a game in his Trojan career and the school retired his No. 25 in 2007. He was inducted into the College Basketball Hall of Fame in 2018.

Not well known: When Westphal was inducted into the Basketball Hall of Fame in Springfield, Mass., in 2019, less than two years before he died from brain cancer, he was presented with a No. 25 Falcons jersey from his Aviation High Days that celebrated his All-CIF career.

Don Baylor, California Angels designated hitter (1978 to 1982): Two seasons after he arrived in Anaheim (and wore No. 12 in ’77), he was the AL MVP with 36 homers, a league-best 139 RBIs and 120 runs scored, with 186 hits and 22 stolen bases. That was also his only All Star season, and the only time in his 19 seasons he topped 100 RBIs (although he had 99 with the Angels in ’78).

Tommy Edman, Los Angeles Dodgers infielder/outfielder (2024 to present): The 2024 National League Championship Series MVP … for a utility player the team picked up at the trade deadline in a three-team transaction, stuck on the disabled list and virtually out of sight, out of mind by everyone else? A 2021 Gold Glove winner at second base with St. Louis was a prized pull by the Dodgers, looking for versatility and durability from a switch-hitting hole-plugger. In that NLCS six-game win by the Dodgers over the New York Mets, Edman was 11 for 27 (.407) with three doubles, a home run and 11 RBIs, with 17 total bases, going back and forth from center field to shortstop, from No. 9 in the lineup to No. 4. Surprise!

Darrin Nelson, Pius X High football running back (1974 to 1977): The 5-foot-9 All-CIF performer was eventually inducted into the College Football Hall of Fame for his career at Stanford, where he excelled as a runner and receiver in coach Bill Walsh’s offensive scheme. Nelson was the first player in NCAA history to rush for more than 1,000 yards and catch more than 50 passes in a season — a feat he accomplished three times. As a senior he had 1,104 yards rushing and 846 yard receiving (on 67 catches). He led Stanford with career rushing yards (4,033), receptions (214), touchdowns (40) and set an NCAA record with 6,885 career all-purpose yards. He had an 11-year NFL career with Minnesota and San Diego. He became a senior associate athletic director at Stanford and UC Irvine.

Ronald Jones, USC football running back (2015 to 2017): The Top 10 list of the Trojans’ all-time career rushing yards starts with Charles White (5,598, from ’76 to ’79) then goes to Marcus Allen (4,682 from ’78 to ’81) and then … neither Ricky Bell, Anthony Davis, Mike Garrett, Reggie Bush nor O.J. Simpson. Ronald Jones is third at 3,619, on 519 carries, thanks to a junior season where he had 1,550 yards on 261 carries. His career average of 6.1 yards per carry is third only to Bush (7.3) and Joe McKnight (6.3) with at least 300 career carries. Jones’ 39 rushing touchdowns is also fifth on the all-time list. And his total yards from scrimmage of 3,921 is fourth all time.

John Lee, UCLA football kicker (1982 to 1985): Maybe the most prolific kicker in NCAA history, the two-time All-American set school records for field goals in a game (6), season (32, in 1984) and career (85, including bowl games). He held the NCAA highest career percentage record (85.9). A 2001 inductee into the UCLA Athletic Hall of Fame.

Have you heard this story:

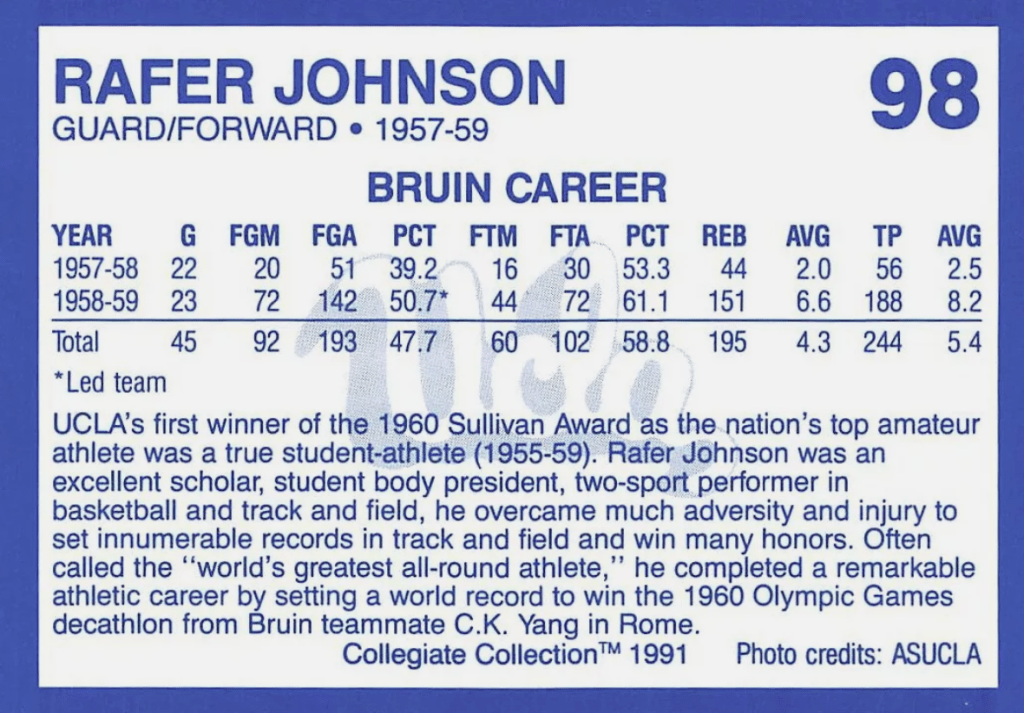

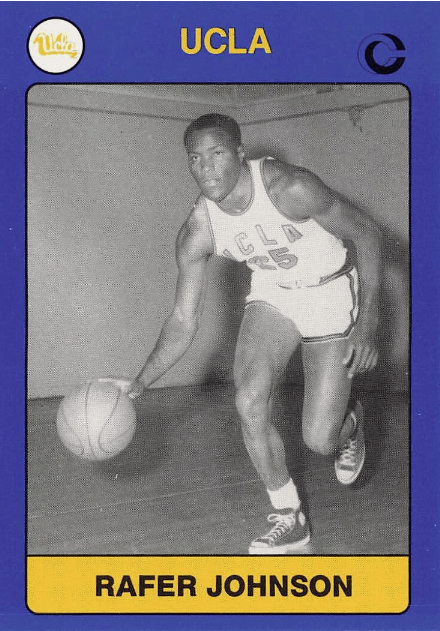

Rafer Johnson, UCLA basketball guard/forward (1957-58 to 1958-59):

The Rome 1960 Olympic gold medalist in the decathlon, having also won silver in Melbourne in 1956, Johnson spent his athletic career in between the Olympiads playing basketball for Bruins coach John Wooden, a starting 6-foot-3 swingman on the ’58-’59 team that went 16-9.

As Joe Posnanski once wrote about Johnson in Sports Illustrated in 2010: “Wooden remembered him as a great defensive player and, of course, the best athlete he ever coached. Wooden would sometimes say that one of his great coaching regrets was holding back some of his early teams. ‘Imagine,’ Wooden would sometimes say, ‘imagine Rafer Johnson on the break.’ What Johnson remembered, though, were Wooden’s bits of advice, the small and carefully crafted mottos that encapsulated all that Wooden had learned about sports. Understand that by the time Johnson played basketball at UCLA, he was already an international sensation. He was named Sports Illustrated Sportsman of the Year in 1958. He was class president at UCLA and a popular speaker for various causes and someone who bridged the gap, made everyone across all lines feel good about America. But he was also an athlete, and he was hungry for the ultimate success, and perhaps more than anyone else he listened to Wooden, wrote down the words, studied them, memorized them, repeated them to himself while he competed. “You know what excuses are?” Johnson said. “Excuses are just ways to fool yourself.” Johnson was a charter member of the UCLA Athletic Hall of Fame in 1984.

Jim Abbott, California Angels pitcher (1989 to 1992):

The first-round pick out of the University of Michigan, who many weren’t willing to take a chance on based on being born without a right hand, won 12 games his rookie season without having spent a day in the minors. The 18 games he won at age 23 in his third season in Anaheim, with the AL fourth-best 2.89 ERA in 243 innings, had him third in the Cy Young voting. In 1992, Abbott was awarded the Tony Conigliaro Award, given annually by the Boston Red Sox to a Major League player who overcomes an obstacle and adversity through the attributes of spirit, determination, and courage. He was traded to the New York Yankees in a deal that included J.T. Snow, then traded back to the Angels from the Chicago White Sox at the 1995 deadline and reversed his number — to No. 52 – the last season going 2-18 and a 7.48 ERA in 27 games.

Mickey Flynn, Anaheim High football running back (1954 to 1956):

Just before Disneyland opened, the main attraction in Orange County was Anaheim High’s two-time CIF Player of the Year known as “The Galloping Ghost of La Palma Park.” Some of that had to do with the fact that in the 1950s, he was playing on the dimly lit fields, and it would appear that Flynn came in and out of the shadows and then reappeared downfield to finish a long gain.

The first time he touched the ball in a varsity game as a sophomore, he ran 95 yards for a touchdown. As a junior, Flynn had 76 carries for 1,184 yards and 22 touchdowns. He was the only non-senior named to the All-Southern California CIF 1955 team.

It all came together in what’s still called the Greatest High School Football Ever Played in Southern California History — the 13-13 tie in dense fog at the Coliseum when his 12-0 Anaheim team faced Randy Meadows and 12-0 Downey High for the CIF championship on Dec. 14, 1956. Flynn had 17 carries for 134 yards and a 62-yard first-quarter TD run as well as a third-quarter TD for both his team’s main scores.

Meadows, who injured his shoulder tackling Flynn in the first quarter, came back and had 112 yards rushing on 10 carries and scored on a 69-yard TD run, also in the first quarter. The game has been documented in the film “A Last Hurrah.” The late Times sportswriter John De La Vega had described in the paper the morning of the contest that it was “the dangedest football Donnybrook in Southland prep annals.”

Flynn would score 55 touchdowns and accumulate 3,681 yards in three seasons as a 5-foot-7 tailback. He and Meadows became teammates at the following Shrine East-West All Star game, which drew another 85,000 fans at the Coliseum. Flynn, who averaged about 14 yards a carry in his career, was the first athlete enshrined in the Orange County Sports Hall of Fame in 1986. Flynn played a season at Long Beach City College, moved on briefly to Arizona State under Frank Kush, but was gone before anyone really knew he was there.

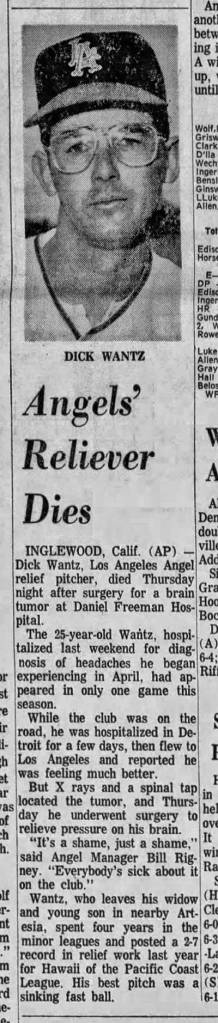

Dick Wantz, Los Angeles Angels pitcher (1965):

Born in South Gate and a graduate of Artesia High in Lakewood, Wantz had an impressive spring training for the Angels in 1965. The former pitcher at Cerritos College in Norwalk went to Cal State L.A., where he had a 5-1 record in 1961 and was named to the California Collegiate Athletic Association All Star team.

From the Angels’ D-League team up through Triple-A, Wantz never had a win-loss record above .500 until he was 2-1 in the Arizona Instructional League in 11 games and five starts.

Wantz’s big-league debut came in the season opener on May 13, 1965, two days after his 25th birthday. Entering the eighth inning at Dodger Stadium with the Angels trailing Cleveland 5-0, Wantz struck out Max Alvis. He gave up back-to-back doubles and a single that resulted in a pair of runs, but then struck out Ralph Terry before getting Dick Howser to ground out to shortstop Jim Fregosi. The Angels pinch-hit for him in the bottom of the eighth in a game they would lose, 7-1.

But soon, Wantz was hospitalized. He had a brain tumor surgery when he never regained consciousness. He was hospitalized while the Angels were on a road trip to Detroit after complaining of migraine headaches, and then sent home to Artesia to recover.

He was back in the hospital and put on the disabled list when he had headaches, which team Dr. Robert Woods suspected was the result of a blood virus. After three neurosurgeons were put on the case, the operation came on his cerebral spinal canal and it was discovered that cancer in both sides of his brain. Woods said Wantz lapsed into a coma and never came out of it.

The 6-foot-5, 195-pound righthander died a month later at Daniel Freeman Hospital in Inglewood.

In an obituary for Wantz that appeared in the San Bernardino County Sun, Angels pitching coach Marv Grissom said after seeing what he did in spring training: “He can be a great pitcher.” Grissom was a pallbearer at his funeral as was Angels farm system director Roland Hemond.

Wantz played basketball, golf and baseball at Artesia High. At Cerritos JC, he led the team to league titles in 1959 and ’60.

Wantz left a wife and 5-year-old son.

Bernie Casey, Los Angeles Rams flanker (1967 to 1968): The last two seasons of his eight-year NFL career were in L.A., going to the Pro Bowl in ’67, when he amassed 871 yards receiving for eight touchdowns in starting all 14 games. Then can the acting roles, as he saw Jim Brown make a post-NFL career work for him in that field. In 1969, he was in “Guns of the Magnificent Seven,” and then win Brown in some roles.

George Hendrick, California Angels outfielder (1986 to 1988): Having roots in South L.A. as a standout at Freemont High meant Hendrick finally got to circle back and play in Southern California at the end of his 18-year pro career, part of the Angels’ ’86 AL West Division-winning team. Make note in his SABR.com bio: His talents playing semipro baseball once caught the eye of Whitey Herzog, the director of the New York Mets’ player development. “I saw George in a sandlot game in Watts. He was the only guy there of any consequence. He had great tools. If Oakland hadn’t picked him, we would have gotten him in a minute.” Oakland made Hendrick the No. 1 overall choice in the January 1968 free-agent draft phase. Hendrick was a Los Angeles Dodgers hitting coach for the 2005 season (wearing No. 22).

Haven Moses, Fermin de Lasuen High football (1961 to 1965): Before he became a Pro Bowl receiver in the NFL for 14 years with Buffalo and Denver, Moses was among the first students at Ferman de Lasuen High in San Pedro. He also had two seasons at L.A. Harbor College, transferring to San Diego State, before his NFL career blossomed. In Terry Frei’s 2009 book,“’77: Denver, the Broncos and a Coming of Age,” Moses explained how his first two years in high school were taking a 15-mile bus trip with a handful of coins from his home in Compton to Harbor City, then Wilmington, then San Pedro to attend the Catholic school in San Pedro, bypassing nearby Centennial High, and because he couldn’t get into Serra or Mount Carmel. The family had lost its home at 110th Street and Avalon Boulevard near the Coliseum when Moses was 10, so they moved in with nearby family. When Moses started at Fermin de Lasuen, the all-boys school was in its second year and had only ninth and tenth graders. In football, the school’s fledging program won a lower-division CIF championship with its first senior class, when Haven was a junior playing defensive back and running back. At Harbor College, Moses was angling to attend USC when San Diego State coach Don Coryell recruited him after seeing him score three touchdowns against San Diego City College. “They were down-home guys at San Diego State,” Moses said. “SC was very pretentious. Then Coryell and (assistant coach John) Madden came to my house in Compton, and that was the thing that impressed me the most. They told my mom two things: they’d make sure I got an education and that I’d have fun. No other coach talked about that and no other coach came to my house.” USC coach John McKay was upset and told Moses that since they were both Catholic, than means “you don’t lie” about a commitment. “My mother was heartbroken and wouldn’t talk to me for about six weeks. She was bragging that her son was going to SC, and all of our family was in Southern California. I was the hottest thing in our family since the automobile and it took some time for me to get through that, but I was happy.”

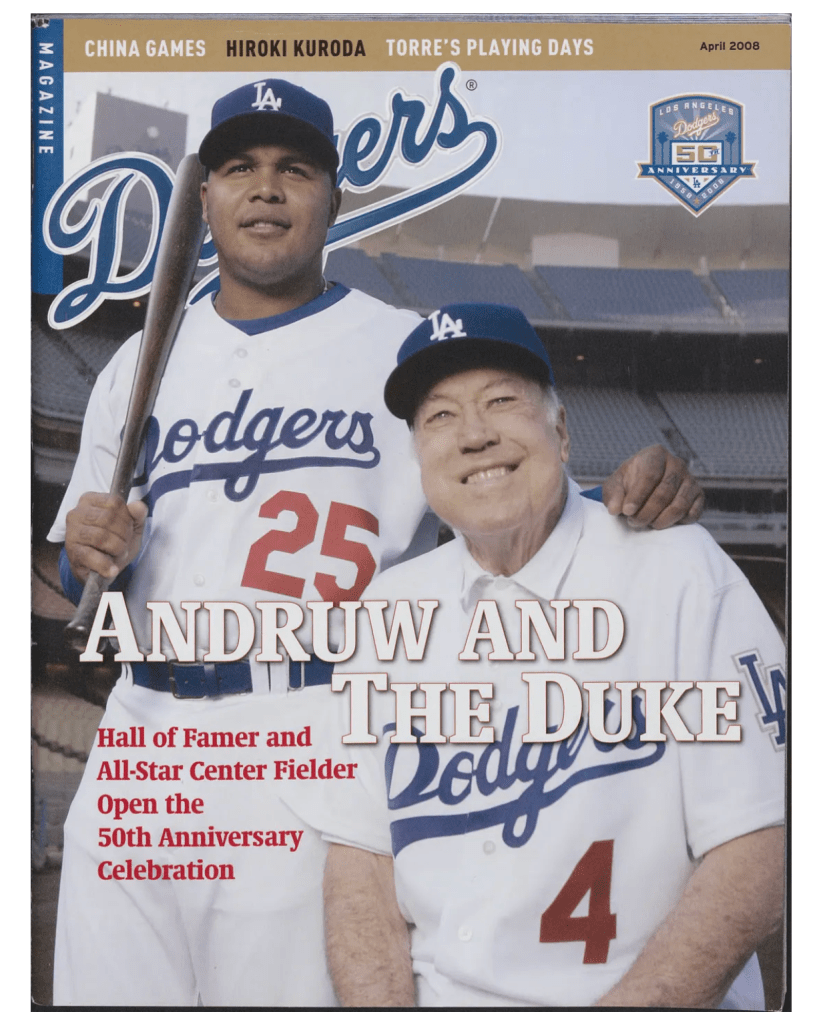

Andruw Jones, Los Angeles Dodgers center fielder (2008):

Name the four players voted into the Baseball Hall of Fame who wore No. 25 during their time with the Los Angeles Dodgers. Rickey Henderson (2003) and Jim Thome (2009) are two of them, just for one season, at the end of their careers. Mike Piazza (1992) wore it for his first 21 games as a September callup before switching to No. 31 for his Rookie of the Year/first NL All Star season (because veteran third baseman Tim Wallach wanted No. 25).

Then there was Jones.

His first 12 seasons were establishing himself as a 10-time Gold Glove winner and five-time All Star by the time he was 30 on a HOF trajectory. He was second in the 205 NL MVP voting with 51 homers and 128 RBIs. In December of 2007, the Dodgers signed the free agent to a two-year, $36.2 million deal. The $18.1 million average annual value was the fifth greatest in baseball at the time.

The team had big plans for him. See this issue of a team game program:

Jones had notorious poor conditioning and was living off his past when, by May 25, he was on the disabled list for the first time in his MLB career, injuring his knee in batting practice. He tore cartilage. His season was done when he was put on the 60-day DL on Sept. 13. The end result was the Dodgers making a deal to add Manny Ramirez at the trade deadline and promoting Matt Kemp to play center field. Jones hit only .158 in 75 games with three home runs and 14 RBI and had a -1.6 WAR in only 238 plate appearances. His 35 OPS+ tied for worst in Dodger history of the live-ball era (minimum 200 plate appearances). He missed a total of 76 games due to knee surgery as the team won the NL West and went to the NLCS without him. The Dodgers had Kemp, Ramirez, Andre Ethier and Juan Pierre for the 2009 season, leaving Jones on the outside. They reached a buyout agreement in January 2009 and Jones went on to squeeze out just as miserable seasons in Texas, Chicago and New York, plus Japan, as the Dodgers kept paying him through 2014. Maybe the Braves retired his No. 25 in 2023 but he wasn’t happening in L.A. In 2012, was arrest for domestic battery when he attached his wife and threatened to killer her. He pleaded guilty, was fined and given probation. That apparently didn’t matter much any longer as Jones was voted into the Hall in his ninth year of eligibility in 2026.

As a footnote: In 1938, future Hall of Fame center fielder Kiki Cuyler wore No. 25 for the Brooklyn Dodgers.

We also have:

Tim Wallach, Los Angeles Dodgers third baseman (1993; also wore No. 29 from 1994 to 1996 with the Dodgers and No. 23 for the California Angels in 1996)

Bobby Bonilla, Los Angeles Dodgers third baseman (1998)

David Freese, Los Angeles Dodgers first baseman (2018 to 2019)

Bobby Bonds, California Angels outfielder (1976 to 1977)

Mitch Kupchak, Los Angeles Lakers forward (wore No. 41 in 1981-82; switched to No. 25 from 1983-84 to 1985-86)

LeRoy Ellis, Los Angeles Lakers forward (1963-64 to 1965-66; switched to No. 14 from 1971-72 to 1972-73)

Jerry Gray, Los Angeles Rams cornerback (1985 to 1991)

Danny Manning, Los Angeles Clippers forward (1988-89, then switched to No. 5 from 1990 to ’94)

Eddie Jones, Los Angeles Lakers forward (1994-95 to 1995-96; also wore No. 6 from 1996-97 to 1998-99).

Pete Trgovich, UCLA basketball guard (1972-73 to 1974-75)

Earl Watson, UCLA basketball guard (1997-98 to 2000-01)

Chris Pronger, Anaheim Ducks defenseman (2006-07 to 2008-09)

Melvin Gordon III, Los Angeles Chargers running back (2019, also wore No. 28 for the Chargers rom 2015 to 2018)

Sony Michel, Los Angeles Rams running back (2021)

Anyone else worth nominating?

1 thought on “No. 25: Tommy John (and Dr. Frank Jobe)”