This is the latest post for an ongoing media project — SoCal Sports History 101: The Prime Numbers from 00 to 99 that Uniformly, Uniquely and Unapologetically Reveal The Narrative of Our Region’s Athletic Heritage. Pick a number and highlight an athlete — person, place or thing — most obviously connected to it by fame and fortune, someone who isn’t so obvious, and then take a deeper dive into the most interesting story tied to it. It’s a combination of star power, achievement, longevity, notoriety, and, above all, what makes that athlete so Southern California. Quirkiness and notoriety factor in. And it should open itself to more discussion and debate — which is what sports is best at doing.

The most obvious choices for No. 13:

= Wilt Chamberlain: Los Angeles Lakers

= Paul George: Los Angeles Clippers

= Cobi Jones: Los Angeles Galaxy

The not-so-obvious choices for No. 13:

= Kenny Washington: UCLA football, Los Angeles Rams

= Keenan Allen: Los Angeles Chargers

= Max Muncy: Los Angeles Dodgers

= Tank Younger: Los Angeles Rams

= Cotton Warburton: USC football

= Caleb Williams: USC football

= Todd Marinovich: USC football

The most interesting story for No. 13:

Kenny Washington: UCLA football halfback (1937 to 1939); Hollywood Bears halfback (1940 to 1942); Los Angeles Rams running back (1946 to 1948), Los Angeles Angels infielder (1950).

Southern California map pinpoints:

East Los Angeles; Hollywood; Westwood (UCLA); Los Angeles (Gilmore Stadium, Coliseum, Wrigley Field)

On Sept. 29, 1946, Kenny Stanley Washington strapped on a modest, leather football helmet without a facemask. There were the white horns of the Los Angeles Rams hand-painted on the side. He was called into the second half of the team’s season opener at the Los Angeles Coliseum against Philadelphia to sub in injured star quarterback Bob Waterfield and ineffective backup Jim Hardy.

It had been six months since Washington signed a contract with this newly-transplanted NFL franchise, so the team’s season opener became even more historic.

“Kingfish” Washington, also known as the “Sepia Cyclone,” was on the same turf where he was the first All-American in UCLA football history, eventually the school’s first College Football Hall of Fame inductee.

The now 28-year-old out of nearby Lincoln High in East L.A. became the first Black player to reintegrate the NFL, and the first professional Black athlete on the progressive West Coast.

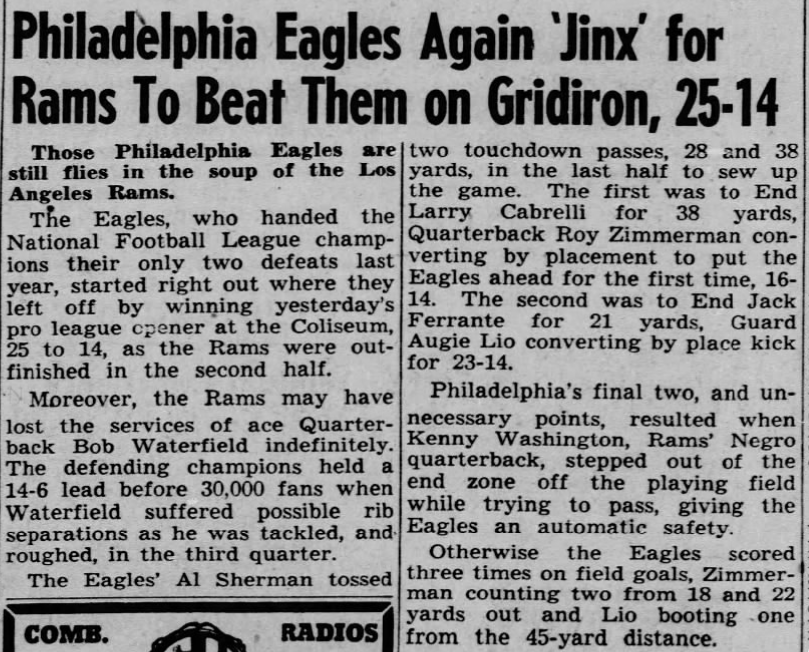

Los Angeles Times’ sports editor Paul Zimmerman noted that, as 30,553 perspiring fans saw the world champion Rams make their first title defense in a 25-14 loss, Washington’s contribution to the final score was mentioned in the fifth paragraph, under the subhead “Gift Pair”:

A story in the Los Angeles Valley Times also barely noted Washington’s existence, again in the fifth paragraph:

Washington completed just one pass in seven attempts for 19 yards. He had no rushing totals.

It may not have blotted out more than a decade of an exclusionary, unwritten policy about franchises signing anyone of that particular race. This was still 6 1/2 months before Washington’s former UCLA football teammate, Jackie Robinson, made much bigger headlines by breaking Major League Baseball’s color barrier with the Brooklyn Dodgers.

These days, they erect statues, rebrand stadiums and build museums to remember Robinson. In Lincoln Heights, at the intersection of North Broadway and Lincoln Park Avenue near at Lincoln High football field, there is a square named after Washington that wasn’t put up until 2014.

Maybe comparing Robinson to Washington isn’t fair. But the truth is that Washington, had he not died far too young at age 52 in the summer of 1971 from a rare blood disorder, might have had more to say about it. His friend Robinson died about a year later at age 53. All that’s left now are changing narratives.

And yet it was Robinson who was once quoted: “Kenny Washington was the greatest football player I have ever seen. He had everything needed for greatness – size, speed and tremendous strength. … It would be a shame if he were to be forgotten.”

In the the 2022 book from Dan Taylor, “Walking Alone: The Untold Journey of Football Pioneer Kenny Washington,” it is noted that Washington still holds the Rams’ franchise record for longest run from scrimmage – 92 yards, accomplished on Nov. 2, ‘47, midway during his brief pro career from 1946 to ’48 that tried to change the perception of L.A. and the NFL.

We may never see a day in the NFL when everyone wears Washington’s No. 13 – or at least sports a patch for it on their jersey.

Fritz Pollard is often considered “The Jackie Robinson of the NFL” in many historical accounts.

Perhaps September 29, when Washington made his first NFL appearance, it could be on the league’s calendar as April 15 has been for MLB?

“Without question,” Taylor once told us. “It is a bit surprising that it has never before been held up as an important date in the history of the NFL. I certainly understand that when Jackie Robinson debuted with the Dodgers baseball was far-and-away America’s national pastime. In 1946 professional football was not the popular sport it is today. Jackie’s signing thus received wide spread attention, far more than Kenny’s and that plays a big part in why it is remembered and he is celebrated today.

“I also understand that Fritz Pollard and other African-American players were tremendous pioneers in the 1920s and we don’t want to diminish their contribution or accomplishments. Still none of it should make what Kenny Washington achieved any less important. What he overcame, and all he had to deal with was tremendous and should be remembered. September 29 is a date the league should always showcase.”

Washington was inducted into the National Football Foundation Hall of Fame in 1956. He was a charter member of the UCLA Athletic Hall of Fame in 1984, 45 years after he played for the Bruins. He is frequently remembered during Black History Month celebrations.

Taylor writes about how when the two were at UCLA, Washington became a calming influence for Robinson, often seen as volatile and frustrated. Washington went with Robinson on walks around the Westwood campus to talk about dealing with life issues.

Taylor is also profoundly baffled why more isn’t known about how Robinson lobbied Branch Rickey to sign Washington as the Dodgers, and MLB’s, second Black player. Washington, not Robinson, was UCLA’s first black baseball player. It appears the Dodgers considered signing him first, but Washington’s health was an issue as well as Washington’s intentions to give pro football a try.

In 2022, on the 75th anniversary of Washington’s first NFL appearance, as the Rams were marching toward a Super Bowl title, it was noted that the roster was led by Black stars such as Aaron Donald, Jalen Ramsey, Odell Beckham Jr. and Von Miller. It was a franchise also known for Hall of Fame players with retired numbers for Eric Dickerson, Marshall Faulk, Deacon Jones, Jackie Slater and Isaac Bruce. It had a legacy of Black running backs that included Deacon Dan Towler, Dick Bass, Cullen Bryant, Lawrence McCutchen, Stephen Jackson and Todd Gurley.

But Washington’s name rarely comes up in the conversation.

Could the Rams at least sport a No. 13 patch somewhere, or post a plaque, somewhere in SoFi Stadium, just as the Coliseum has a plaque for him in its Court of Honor – which is just for his UCLA achievements?

“I found Kenny Washington to be a remarkable life story,” Taylor says. “He’s undeniably one of the great football players of all time and one of America’s greatest athletes. It’s unfortunate he has been forgotten. Someone so talented who made such an impact on not just UCLA, but Los Angeles, the Rams, and the NFL, should not just be remembered but held in great regard and celebrated.”

“Any of those suggestions would be appropriate,” said Taylor. “This is a big part of the Rams heritage. They should celebrate it. It’s more than a little perplexing that they haven’t. I don’t understand how something so significant has been ignored for all these years.”

Washington should be easily recognizable as one of the true legends of Los Angeles sports.

A career that launched at Lincoln High found him next at UCLA.

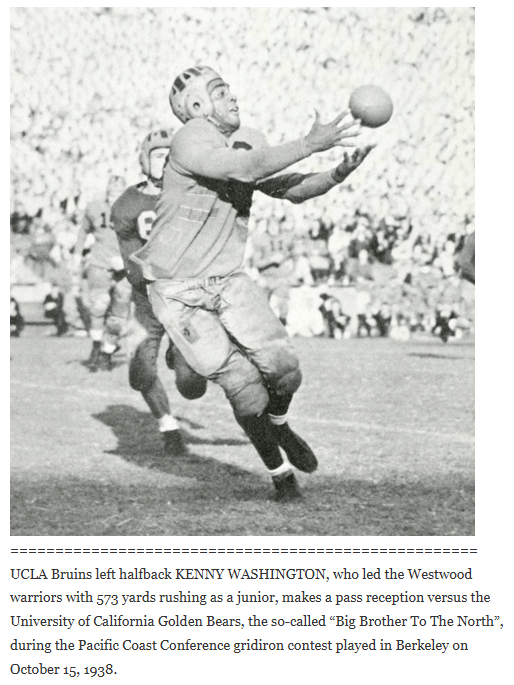

As a sophomore in 1937, he ran for 530 yards and four touchdowns, and completed 34 of 72 passes for 495 yards and five TDs. In a 19-13 loss to USC, some newspaper accounts credited him with making a pass 62 yards in the air to Hal Hirshon. Others said it was 72 yards — a college football record at the time. That season he also had two interceptions on defense, had six kickoff returns for 160 yards, an average of 26.7 per touch.

As a junior in 1938, he ran for 573 yards and five TDs, and completed 21 of 65 passes for 214 yards, two touchdowns and 11 interceptions. He also had five receptions for 47 yards and a TD. On defense he had three interceptions, had seven kickoff returns for 161 yards and returned one punt for 10 yards.

He led the nation in total offense and was equally as impressive on defense during the Bruins’ undefeated season of 1939, as the team was ranked No. 7 in the final polls. He ran for 811 yards (4.8 a carry) with five touchdowns, and threw for 559 yards (37 of 91) with seven TDs and eight interceptions. He also had two receptions for 51 yards, made one interception on defense, returned six kicks for 107 yards and one punt for 18 yards. The Helms Foundation named him the Athlete of the Year for all of Southern California in ’39. He won the Fairbanks Award as the 1939 college football player of the year. Liberty Magazine named him Back of the Year.

With a career rushing total of 1,914 yards, it stood as a school record for 34 years and left such an impression that, in 1955, the Helms Foundation named UCLA’s Washington and USC’s Morley Drury the greatest football players in the area up to that time.

When no NFL team drafted him, Washington spent three years in the Pacific Coast Professional Football League with the Hollywood Bears, whose owner Paul Schissler named after his UCLA alma mater. Washington led the team to an 8-0 season in ’41 and league title as the season was cut short due to the attack on Pearl Harbor. Most of the PCPFL rosters were lost to World War II recruitment, and Washington was injured most of that season as the Bears went 0-4 and then disbanded for the ’43 season.

As soon as his football career was done, baseball came back into focus. Even as he tried to play on knees operated on five times.

After New York Giants manager Leo Durocher gave him a tryout, Washington, at age 31, was going to get up to speed for the 1950 season with the Pacific Coast League’s Los Angeles Angels. Baseball was still in his blood, as his father, Blue Washington, pitched in the Negro Leagues. Washington was a star shortstop at Lincoln High and, as a sophomore, named All-City. After becoming the first Black baseball player at UCLA, he hit .397 with a team-best four homers and 19 RBIs in the 17-game season and was All-California Intercollegiate Baseball Association as a shortstop.

With the Angels, played in just six games and failed to get a hit in nine at bats as a third baseman. Covering third base on a stolen base attempt, he was spiked by the runner and injured. He opted to retire from all of pro sports at that point.

A thorough baseball bio on Washington’s life is part of the Society of American Baseball Research archives, where it points out that in 1958, Walter O’Malley recruited Washington to serve as a consultant to the newly moved Los Angeles Dodgers. He aided the business department and Dodgers scouts and when the Dodgers succeeded in landing one of the most coveted amateur players in the country, Willie Crawford, in June of 1964, sportswriters pointed out that Washington played a major role in the deal.

A headline in Slate’s culture section posted in 2021 asked: “Why Isn’t Kenny Washington an American Icon?”

There is this 16-minute documentary that has come out on him called “Kingfish.” And there is this plaque among the 60-plus in the L.A. Coliseum’s Memorial Court of Honor.

But what really is celebrated?

Because of what was happening in the world of sports in general and in the NFL specifically, Joe Posnanski uses his 2025 book, “Why We Love Football: A History in 100 Moments,” to pinpoint March 21, 1946 as a date perhaps with more historical importance than that September day at the Coliseum that followed.

Cleveland Rams owner Dan Reeves saw migration to the West a fine business move, and new commissioner Bert Bell was ready, willing and able to help him do that. But Los Angeles pushed back.

Halley Harding, sports editor at the Los Angeles Tribune and a former football star in college, pro basketball player and a Negro League shortstop, spoke at a Coliseum Commission meeting to discuss this proposition. Harding reminded the committee that as a publicly owned facility, paid for by many African-American tax payers. He talked about the NFL’s agreement to ban Black players to that point. He talked about Washington, and wondered how he had been ignored by the NFL for all he accomplished at UCLA. Why did no NFL team draft him out of college? Why did no team sign him as a free agent?

Why, for that matter, had no MLB team signed him?

The day after that meeting, the Rams invited him to a tryout. Two months later, Washington was signed, along with his friend Woody Strode, and after attending the team’s training camp in Compton, both would play on that Sept. 29, 1946 game for the Rams.

In the Los Angeles Tribune of March 23, 1946, a staff story read: “Yesterday TRIBUNE sports editor Halley Harding’s one-man crusade against the National Football league’s patent, if unwritten, law against Negro players paid off in full … Washington will be the first Negro to play with a National league team since 1933 when Joe Lillard of Oregon last played with the Chicago Cardinals … “

A month later, the Tribune ran a photo of Washington in a hospital bed as he was recovering from a right knee operation “and will be fit as a fiddle when he reports for training in July, his doctor reported.

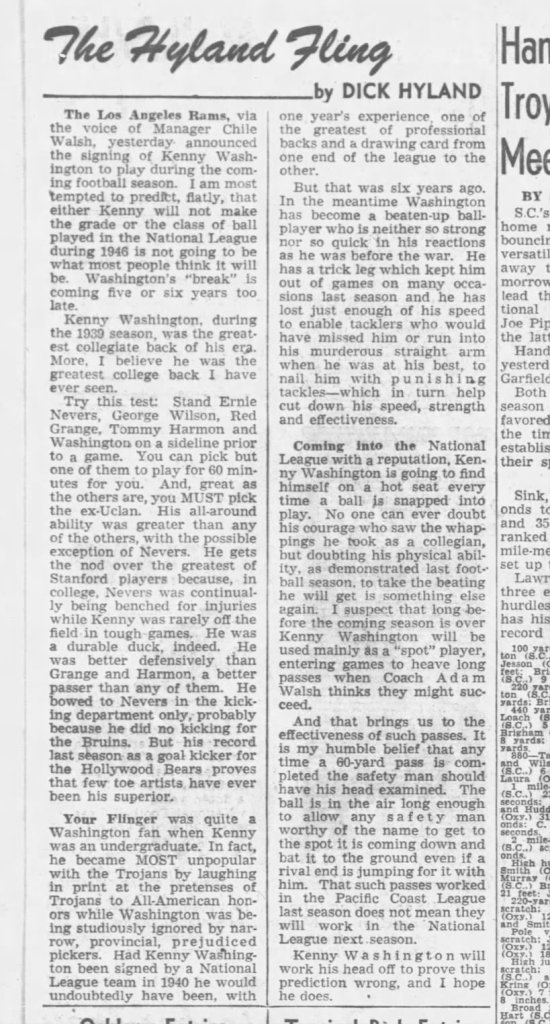

Los Angeles Herald-Express sports editor George T. Davis wrote: “Kenny Washington’s acceptance into the ranks of the National Football League is something that should have happened years ago, just as this great player had graduated with All-American honors from UCLA. (To this, we say, amen). … If he had been taken into the National League in 1940 or 1941 when he should have been and when at his best, this brilliant Negro star might have become the greatest all-around back in the history of the loop.”

The Los Angeles Times’ Dick Hyland added:

In the weeks before Washington’s 1946 debut in the Rams’ season opener, nearly 70,000 fans were at the Coliseum for the Los Angeles Times’ annually-sponsored NFL exhibition game between the Rams and Washington Redskins. The L.A. Times’ Zimmerman noted that Kenny Washington “got a great ovation when he went onto the field” for the first time in a Rams’ jersey.”

But that whole season, “Washington was a shell of himself,” Posnanski wrote. “He’d badly hurt his knee playing semiprofessional football … He was a part time player for three years. He wasn’t the same. Kenny Washington opened the door. But alas, the door opened too late for him.”

In 2024, when the Los Angeles Rams had a “Threaded Through History” exhibit at SoFi Stadium, and unveiled an “an authentic replica jersey” worn by Washington.

Rams director of social justice and football development Johnathan Franklin, a former star running back at UCLA as Washington once was, recognized how he benefited from Washington breaking the color barrier.

“When you think about all the things that he had to overcome, the moments of adversity, the barriers has to break,” said Franklin. “The racial segregation, the slurs, walking into a huddle being the only Black man, walking into cities being the only Black man and still, he continued to … make sure he stood for something greater than himself.”

The NFLShop.com, however, still has a way for fans to show some recognition for Washington in its online store.

Who else wore No. 13 in SoCal sports history?

Make a case for:

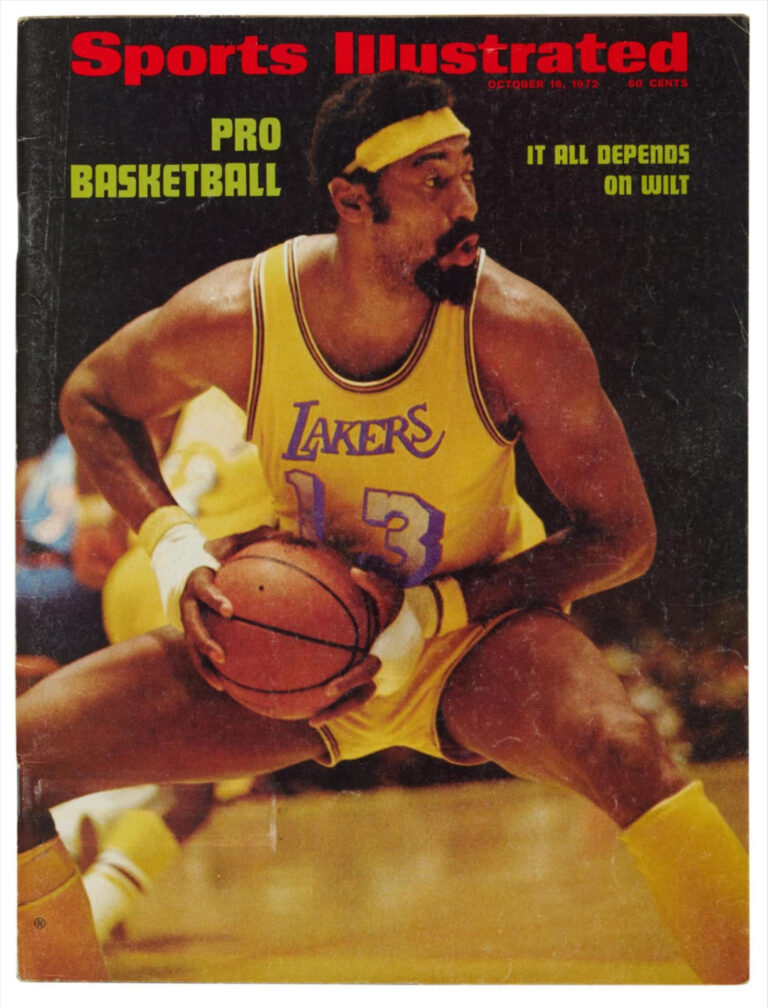

Wilt Chamberlain: Los Angeles Lakers center (1969-70 to 1973-74):

His own Basketball-Reference.com statistical bio lists almost as many nicknames for him to match his No. 13: Wilt the Stilt, The Big Dipper, Dippy, Dip, The Load, Big Musty, The Record Book, Hook and Ladder, Wiltie, Whip, Whipper.

And, Norm. Because his middle name was Norman. Nothing about him was normal.

If triskaidekaphobia is a fear of the No. 13, there must be another name for the fear of having too many nicknames.

He was born in East Coast Philly. His first two years of college were spent in Midwest Kansas. Then he ran off with the Harlem Globetrotters and trotted the globe. After destroying the record and rule books during his first nine seasons as an NBA pro, he was summoned to West Coast Los Angeles. How could the Lakers not be impressed with his abilities. The year before he came to the team, he put up these numbers during a 158-128 victory for his 76ers in a game in Philadelphia on March 18, 1968: 53 points, 32 rebounds, 14 assists to go with 24 blocks and 11 steals (the last two categories weren’t officially recognized at the time).

A new place build a bachelor pad, put down some roots, and see what can happen.

Chamberlain had just five seasons as a Laker, the center of attention with Elgin Baylor and Jerry West as his star-powered presence. He he personified someone larger-than-life in a city that lacked a prominent skyscraper as a tourist attraction.

His 7-foot-1, 275 pound frame was just the scaffolding for this force of nature. The franchise saw him as the missing towering presence in pursuit of their L.A.-based trophy. From 1968-69 through 1972-73, he delivered.

The game’s reigning MVP was the newest star as the Fabulous Forum was just opening. All it took was sacrificing Archie Clark, Darrall Imhoff, Jerry Chambers and likely a blank check to Philadelphia so Lakers owner Jack Kent Cooke could gush over him. He then bestowed Wilt with a ridiculous $250,000 annual salary (vs. the $100,000 given to West) and made him the new team captain. He was the catalyst of the new fast-break offense, ignited by his outlet pass off the rebound. Chick Hearn delighted in him, and we were in awe.

He was the ’72 NBA Finals MVP, in a season where, after Baylor’s retirement and with a coach he could finally understand, the Lakers had the magnificent 33-game win streak and completed a 69-win season by trouncing the rival New York Knicks. He also got them to three other NBA Finals in that time frame, all up against Willis Reed’s Knicks as well.

Lucky for us all, this big Black cat wore the heck out of No. 13 without fear.

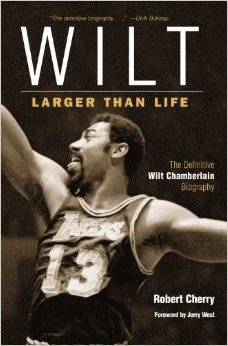

Chamberlain’s life, times, moans and groans, and hopes and dreams and documented conquests has played out bookishly, starting with his own “Wilt: Just Like Any Other 7-foot Black Millionaire Who Lives Next Door” at the end of his Lakers’ days in 1973.

It was followed almost 20 years later by the highly-publicized “A View From Above” in 1991, where the then-50 year old still bachelor calculated his bed partners had surpassed 20,000.

That was about 10,000 short of his record-setting 31,419 regular-season point total. But stats being stats, and Wilt being a four-time MVP, 10-time All-NBA team member, a seven-time scoring champion, an 11-time rebounding champ and even led the league in assists one season, his life was all about trying to quantify his largeness.

He is still discussed that way in today’s conversations and stories about him.

It’s easy to find the data to show he averaged more than 30 points and 20 rebounds a game over more than 1,000 games. He has the single-game record of 100 points, of course, and averaged 50.4 points a game in that ’61-62 season. No one touched him as well in minutes played, either, and he never fouled out.

His final book, “Who’s Running the Asylum? Inside the Insane World of Sports Today,” gave him, in 1997, the self-proclaimed the title as “the # 1 ranked, most outspoken player in NBA history.”

The more journalistic-based projects on him came after his 1999 death, such as “Wilt: Larger Than Life” by Robert Cherry in 2004 and “Wilt, 1962: The Night of 100 Points and the Dawn of a New Era,” by Gary Pomerantz in 2005.

Pomerantz told us in 2012 that book project was “like trying to raise a sunken galleon off the ocean floor. Here was this legendary sports moment just sitting there. And the deeper I got into it, the deeper I saw a snapshot of America beyond the mid-century.”

Chamberlain was also famous for saying “nobody loves Goliath,” which New York Times columnist Dave Anderson once wrote about in his 1999 obituary.

“Maybe nobody loved Goliath, but he was a good guy,” wrote Anderson.

West once said it was a mistake he made — the worst ever — to say Russell was better than Chamberlain. Anderson addressed that comparison.

“Those who saw Chamberlain and Bill Russell will always argue over who was better. For team value, Russell was the center of gravity in the Celtic dynasty: 11 NBA championships in 13 seasons, from 1957 to 1969. For individual dominance, Chamberlain was incomparable; he also dominated two title teams, the 1967 Philadelphia 76ers and the 1972 Lakers.”

We’ll take the later.

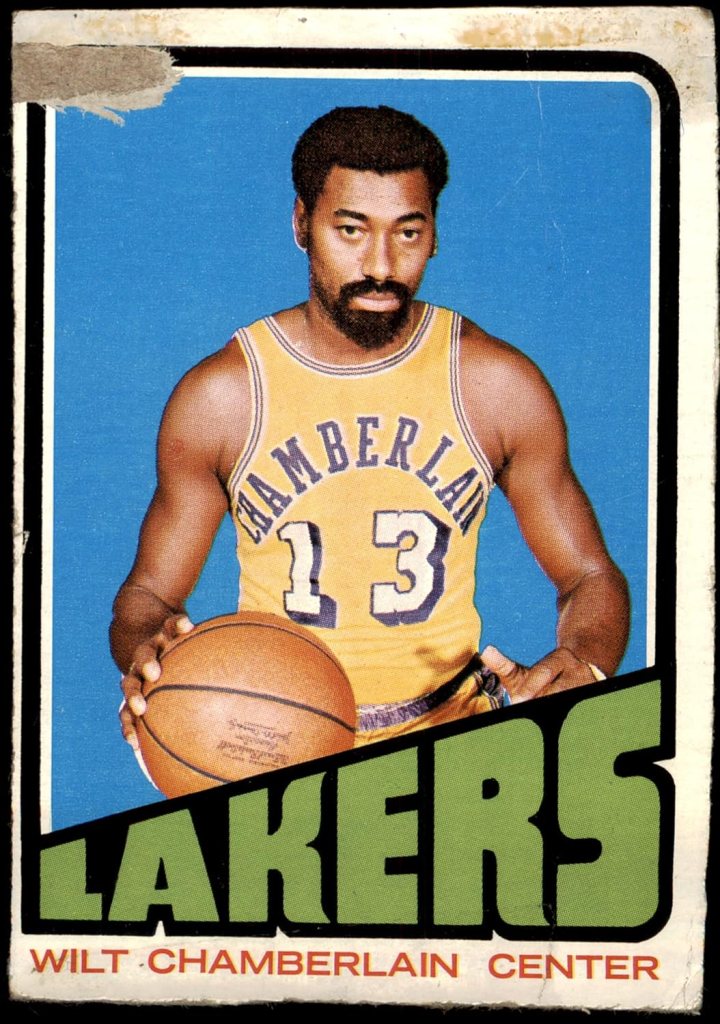

== Our favorite Topps NBA player card as a kid, No. 1 in the 1972-73 set, because players couldn’t wear the team names across the front, so this was an opportunity for Chamberlain to show who where he was really most loyal. On the back, it was all about the house he was building.

== We were were not even a teen yet watching him in the ’72 finals, blown away by his stellar Game 4 and 5 performances to seal a 4-1 series win over New York. In Game 4, he played all 53 minutes of an overtime win and posted 30 points and 24 rebounds at Madison Square Garden. Two days later at the Forum in Inglewood, he had 24 points, 29 rebounds, eight blocks and eight assists in 47 minutes of a 14-point win.

He was 35 at the time. He was playing with a broken hand, bandaged like a white boxing glove. And during the regular season, he had a career-low 14.8 points a game. He used to score that in warmups back when he was with the Philadelphia Warriors and then the 76ers for his hometown fans.

== After his career in the NBA (and the ’73-’74 season as a player-coach for the ABA’s San Diego Conquistadors – a three-year, $1.8 million contract that the Lakers won a court ruling to prevent him from playing while still under contract with them, so he only coached), Chamberlain was often seen on the beaches of Southern California playing volleyball.

There was one time we watched him in a six-man tournament. After winning a match, he walked toward the ocean, alongside the Manhattan Beach pier. He kept walking and walking as the waves splashed his ankles, and then knees, and to his waist. It seemed as he was about to walk to Hawaii, watching the whole way like a submarine periscope.

== During the Lakers’ 1982-83 season that took them back to the NBA Finals (a 4-0 loss to Philadelphia), they actually gave backup center Dwight Jones the honor of wearing No. 13 for 32 games. It was the end of his NBA career, and he wore it the previous 11 seasons. This happened with two of Chamberlain’s former teammates who could have stopped it — Pat Riley as the team’s coach and Jerry West as its top exec.

Nobody loves Goliath?

In 2022, we came across the item that Chamberlain’s elegant Bel-Air estate was up for sale for $11.995 mil. Should have been listed at $13 mil. It is an historic erection, all things considered.

The pleasure palace at 15216 Antelo Place, L.A., 90077, was a reflection of his folklore.

We also came across the story about his ’72 Finals home No. 13 jersey was recently up for auction and got $4.9 million. That’s the third-most expensive NBA jersey ever sold at auction, behind the autographed $5.8 million Kobe Bryant jersey from his lone MVP season (2007-08) and the $10.1 million “Last Dance” 1998 NBA Finals Michael Jordan jersey.

Paul “Tank” Younger, Los Angeles Rams running back (1949 to 1951):

A four-time Pro Bowl player at right half, fullback and left linebacker, he was undrafted out of Grambling University and became the first NFL player from the Historically Black College and Universities (HBCU). He was best known as being part of the Rams’ “Bull Elephant” backfield with Deacon Dan Towler and Dick Hoerner. He switched to No. 35 for the Rams from 1952 to ’57. Younger sits ninth in the Rams’ rushing all-time leaders with 3,296 yard in 100 games. He was the first black player to play in an NFL All-Star Game and became the league’s first black assistant GM with the San Diego Chargers.

Irvine “Cotton” Warburton, USC quarterback (1932 to 1934):

The 1933 and ’34 All-American was just 5-foot-7 and 145 pounds with “cotton” blond hair. He initially guided a ’32 USC team to a 10-0 record and 35-0 win over Pittsburgh in the Rose Bowl for No. 1 rankings. His finest game came in 1933 when he led USC to its 24th consecutive victory, a 33-0 triumph over Washington State. He scored three touchdowns, two on runs of 80 and 75 yards. The 1995 inductee to the USC Athletic Hall of Fame, which also noted he led the Trojans in rushing in 1932 (420 yards) and 1933 (885 yards), also had a sweet post-football existence. His College Football Hall of Fame bio, IMDb.com bio and New York Times obituary tout the fact he won an Oscar for film editing on Disney’s “Mary Poppins” in 1964.

That’s quite a legacy of a Trojan quarterback. As compared to …

Caleb Williams, USC quarterback (2022 to 2023):

The ’22 Heisman Trophy winner and sophomore supreme bedazzled us with 42 touchdowns vs. five interceptions to go with 4,537 passing yards on 500 passing attempts, highlighting the Trojans’ coming-out-of-COVID party with new head coach Lincoln Riley, a package deal from Oklahoma. But Williams’ mercenary message also set an example of how name, image and likeness can be beneficial for someone who wins a Heisman with more eligibility left on his resume. The Dr. Pepper commercial above has him talking about his superstitious number while also bragging about his images on a video game and magazine cover. His Heisman House ads for Nissan he got to show us behind the scenes of what it’s like to be just one of the guys. Will his No. 13 be in the Coliseum royal ring with the other six (or is it seven?) Heisman winners — Nos. 3, 11, 12 20, 33 … who are we missing? Or is Williams really missing out on what makes an athlete in SoCal memorable and significant? For an encore season in 2023, Williams wasn’t in the Heisman top 10 voting (two other Pac-12 QBs were instead) after he threw for 3,633 yards and 30 touchdowns (again vs. five picks) as the Trojans started 6-0 and then lost five of their last six in the regular season.

That’s quite a legacy of a Trojan quarterback. As compared to …

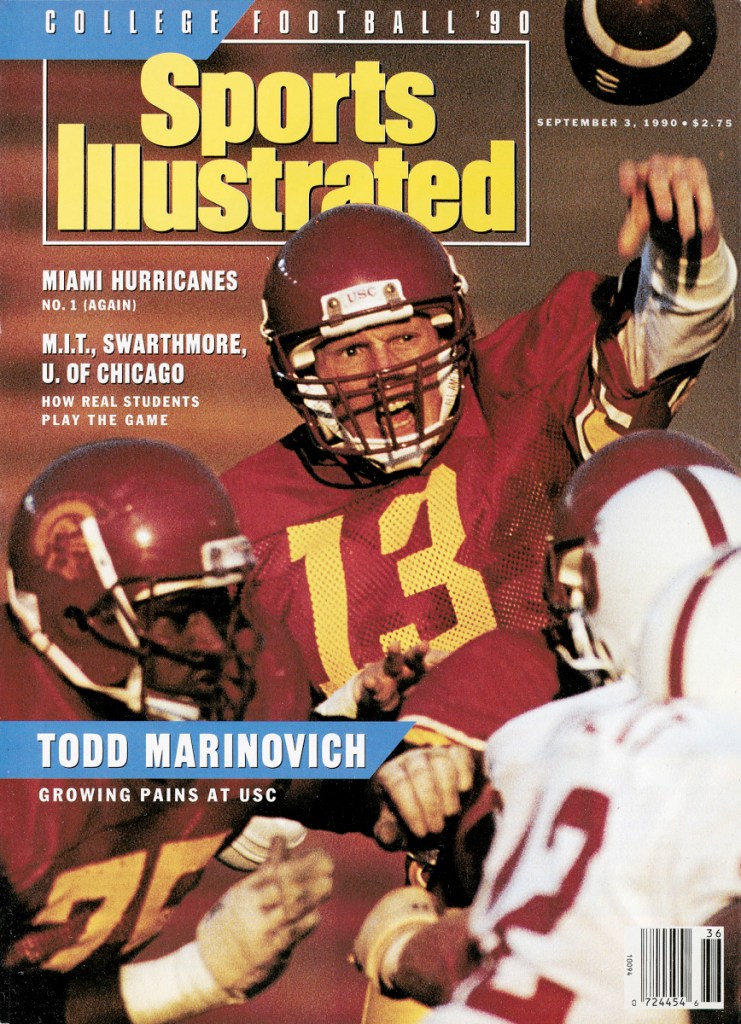

Todd Marinovich, USC quarterback (1989 to 1990):

The first freshman in USC history to start a game (as a redshirt) in 1989 resulted in the team finishing 9-2-1 and a win over Michigan in the 1990 Rose Bowl. Marinovich’s sophomore season was torpedoed by erratic behavior and suspensions. He was arrested for cocaine possession a month after he was struggling in a John Hancock Bowl loss after the ’90 season. He was still a first-round pick by the Los Angeles Raiders in 1991 (wearing No. 12, since Jay Schroeder had No. 13). More substance abuse, legal issues, a trip to the Canadian Football League, time with the Los Angeles Avengers of the Arena Football League (wearing No. 12). More arrests. More recoveries. More artwork demonstrating his processing his life. An ESPN documentary. An autobiography. For more on Marinovich, see the No. 12 entry.

Keenan Allen, Los Angeles Chargers receiver (2013 to 2023, 2025):

Allen became the franchise leader in receptions when he took a short jet sweep pass from Justin Herbert for catch No. 956, passing Antonio Gates, during a Sunday night win over Pittsburgh at SoFi Stadium. Allen has three games with 15 or more receptions over his career, the most in NFL history. That includes an 18-catch, 215-yard day in a Sept. 24, 2023 win at Minnesota. Allen, second behind Gates on the Chargers’ all-time receiving yards list, played his first four seasons with the franchise in San Diego before coming to L.A., making five straight Pro Bowls from 2017 to 2021. The Pro Football Hall of Fame has his 2020 Week 14 game jersey when he recorded his 623rd career reception in his 99th contest, meaning he surpassed Antonio Brown (622 receptions in 100 games) for the most by a player in NFL history in their first 100 games. Allen found out in March, 2024 the team had traded him to Chicago because he wouldn’t take a pay cut or restructure his contract after signing a four-year extension in 2020. “What Keenan Allen has meant to the Chargers for more than a decade cannot adequately be expressed through mere words,” Chargers President of Football Operations John Spanos said in a statement. But when the 2025 season started, the Chargers brought him back. Adding the 70 catches he made in Chicago, Allen became the fastest player in NFL history to have 1,000 career catches on Oct. 5, 2025, doing so in his 159th career game.

(Fred Jewell / Associated Press)

Cobi Jones: Los Angeles Galaxy midfielder (1996 to 2007):

After the Westlake High standout of Westlake Village wore No. 2 as a walkon at UCLA from 1988 to ’91 and helped the Bruins to a 1990 NCAA title, he started as a pro in the English Premiere League before he helped launch Major League Soccer with the hometown team. Jones scored the first goal in franchise history and would establish a club record for appearances (306, scoring 70 goals) as well as winning two MLS Cups and a CONCACAF Champions Cup. Jones’ best year with the Galaxy — 1998, as he was second in MLS with 51 points (19 goals and 13 assists), named to the MLS Best XI and also winner of the U.S. Soccer Athlete of the Year. Jones also managed the team on an interim basis in 2008, served as an assistant on Bruce Arena’s staff for parts of three seasons and was a longtime analyst on the team’s TV broadcasts. The U.S. National Soccer Hall of Famer (inducted in 2011), also on the investor ownership team of the National Women’s Soccer League Angel City club, was the men’s national team’s all-time leader in appearances with 164, becoming the youngest player to reach 100 caps for the U.S. National Team and one of only two to play in every game of the 1994 and 1998 World Cups. He logged 11 games in three World Cup appearances. The Galaxy announced a statue of Jones would join those of David Beckham and Landon Donovan in Legends Plaza outside the team’s Carson home stadium in 2026.).

Max Muncy, Los Angeles Dodgers infielder (2018 to present):

The franchise leader in post-season home runs, Muncy’s 18th inning walk-off in Game 3 of the 2018 World Series ended the longest post-season game ever as far as time (seven hours, 20 minutes) and should get him free drinks forever in Southern California. Rescued from Oakland, the two-time NL All Star is one of only eight players in franchise history to hit more than 200 homers. Add to that seasonal batting averages of .192, .249, .196 and .212 over a four-year stretch, while moving from second base, to first base, to third base, and DH. Muncy got some NL MVP votes in the ’18, ’19 and ’21 seasons. He had two seasons of 36 homers and two more of 35 in his Dodgers’ career.

Joe Ferguson, Los Angeles Dodgers catcher/outfielder (1971 to 1980), California Angels catcher/right fielder (1982 to ’83): He was brave enough to take No. 13 for the first time in the franchise’s history since Ralph Branca wore it in Brooklyn and ended up on the wrong end of the Miracle at Coogan’s Bluff. Ferguson will live in 1974 World Series highlight films as the right-fielder who stepped in front of Jimmy Wynn in right-center threw out Sal Bando trying to score on an eighth-inning sacrifice fly in Game 1. “I didn’t realize how good the throw was because my sunglasses slipped over my eyes,” he said. His two-run homer off Vida Blue gave the Dodgers their only win in the series.

Have you heard the story about:

Paul George, Los Angeles Clippers forward (2019-20 to 2023-24):

In his first three seasons at Indiana, the former Palmdale High standout wore No. 24 as a tribute to Kobe Bryant. Who then switched his number to 8. The story goes that George got some suggestions from Bill Simmons and Jimmy Kimmel to take No. 13, meaning he’d mash his nickname, “PG,” and could go by “PG-13.” So he finally comes to L.A. with a mashup of two of the four names of the Beatles and he decides to mirror a Motion Picture Association of America guideline that may suggest some things he’s doing may not be suitable for children under the age of 13? Maybe think this thing out more for the sequel.

We also have:

Chiney Ogwumike, Los Angeles Sparks center (2019 to 2023)

Steve Bono: UCLA quarterback (1981 to ’84)

Jay Schroeder: UCLA quarterback (1980), Los Angeles Raiders quarterback (1988 to ’91, switched to No. 10 in 1992)

Mark Jackson: Los Angeles Clippers guard (1992-93 to 1993-94)

Bobby Valentine, California Angels outfielder (1973 to ’74, abandoned No. 13 for No. 11 in ’75)

Charles O’Bannon, UCLA basketball forward (1993-94 to 1996-97)

Ruppert Jones, California Angels outfielder (1985 to 1986)

Lance Rentzel, Los Angeles Rams receiver (1971 to ’72), also wore No. 19

Kyle Clifford, Los Angeles Kings defenseman (2010-11 to 2019-20)

Anyone else worth nominating?

So with that, Vin Scully explains the fortunate things related to the No. 13:

Thrilled to see Kenny Washington as honorable mention as he would in fact be my top choice. Though the Stilt’s lifetime achievements dwarf just about anyone’s, Washington was L.A. through and through.

He was a high school legend at Lincoln High and arguably our greatest high school football (and baseball!) player ever, he was the best baseball and football player the UCLA Bruins had ever seen (outshining even Jackie Robinson in both sports), and went on to integrate the NFL as a member of our Los Angeles Rams.

Add to this resume his minor league exploits with the Hollywood Bears (football) and Los Angeles Angels (baseball) and multiple acting roles, and Washington was easily the most accomplished and beloved athlete our young city had ever seen to this point.

LikeLike

When this project goes to the next level – whatever that will be — i’m likely to make Kenny Washington the No. 13 entry. It makes too much sense. I was just a huge Wilt fan it was easy for me to go there.

LikeLike