This is the latest post for an ongoing media project — SoCal Sports History 101: The Prime Numbers from 00 to 99 that Uniformly, Uniquely and Unapologetically Reveal The Narrative of Our Region’s Athletic Heritage. Pick a number and highlight an athlete — person, place or thing — most obviously connected to it by fame and fortune, someone who isn’t so obvious, and then take a deeper dive into the most interesting story tied to it. It’s a combination of star power, achievement, longevity, notoriety, and, above all, what makes that athlete so Southern California. Quirkiness and notoriety factor in. And it should open itself to more discussion and debate — which is what sports is best at doing.

The most obvious choices for No. 36:

= Bo Belinsky: Los Angeles Angels

= Don Newcombe: Los Angeles Dodgers

= Jered Weaver: Long Beach State and Los Angeles Angels

= Jeff Weaver: Los Angeles Dodgers and Los Angels Angels

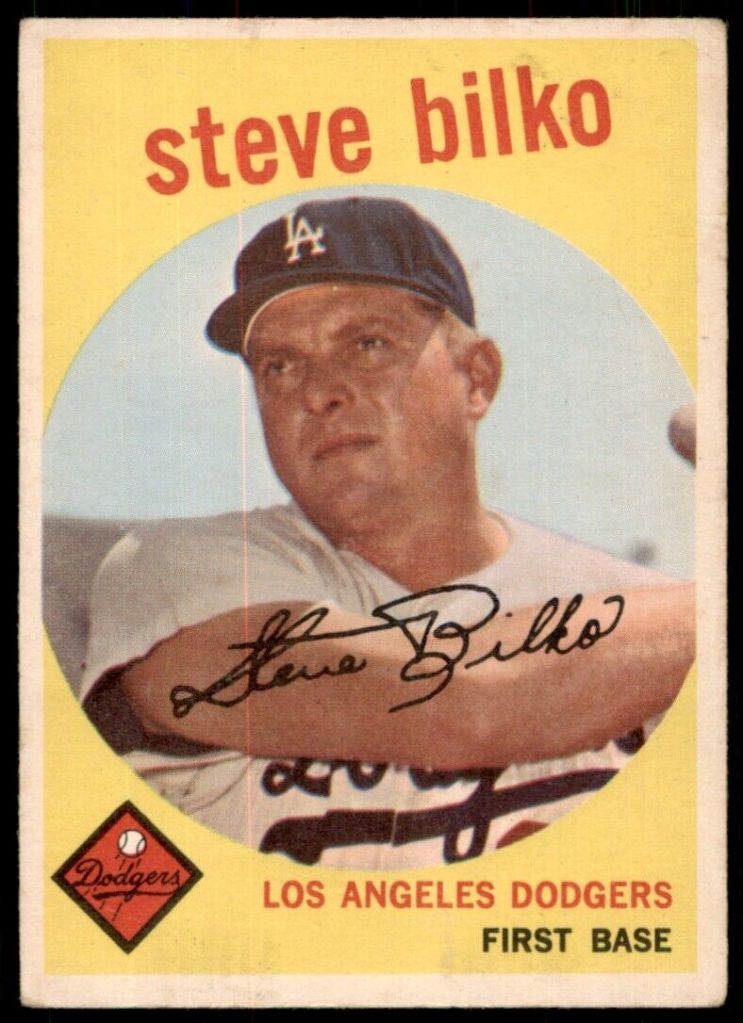

= Steve Bilko: Los Angeles Dodgers

The not-so-obvious choices for No. 36:

= Frank Robinson: Los Angeles Dodgers

= Jerome Bettis: Los Angeles Rams

= Fernando Valenzuela: California Angels

= Greg Maddux: Los Angeles Dodgers

The most interesting story for No. 36:

Roy Gleason: Los Angeles Dodgers outfielder (1963)

Southern California map pinpoints:

Garden Grove, Los Angeles (Dodger Stadium)

Roy Gleason made into eight games with the Los Angeles Dodgers during a September, 1963 callup, but the first seven were just for pinch-running duties. His one at bat, an eighth-inning stand-up double against Philadelphia against left-hander Dennis Bennett at Dodger Stadium, is documented in a box score. The 20-year-old hit a low inside fastball down the left field line.

That was it for the 6-foot-4, switch hitting Garden Grove High product who signed a $55,000 bonus baby contract in 1961. He had turned down a contract with the Boston Red Sox even after Ted Williams personally recruited him. But the Dodgers were concerned he was too much into the L.A. nightlife and wasn’t dedicated enough at that point.

The team was preparing for another trip to the World Series, eventually sweeping the New York Yankees in four straight. Gleason would be given a ’63 World Series ring for his contribution.

But he’d never play in the big league again. Especially after a trip to Vietnam.

He may have been a Dodger. But he wasn’t a draft dodger, even if it made no sense to him why the Army would come looking for him in 1967.

After that ’63 callup, Gleason spent the next three summers in the minors. The team was rebuilding after the 1966 World Series loss, and he was supposed to come to spring training ’67. But that spring, he was drafted for the U.S. Army.

“I was kidnapped by my government,” Gleason would say. The Dodgers, who had protected other players, did not protect Gleason. He heard that his reputation as a carouser worked against him.

“They thought the military would be good for me,” he surmised.

He spent eight months in Vietnam, earned his sergeant stripes and, once, was named soldier of the month. He served in the Army’s 9th Infantry and won the Bronze Star for pulling two injured men out of harm’s way. Then on July 24, 1968, a bomb hanging from a tree exploded that left gaping wounds in his left calf and left wrist, leading to six months in hospitals. He had been leading a group of seven men searching for Viet Cong soldiers. Three of his friends were killed.

When the belongings from his footlocker finally mailed to him, he discovered that his World Series ring was gone. His bitterness multiplied.

Honorably discharged at 26, and with doctors still removing pieces of shrapnel from his leg, Gleason returned to Los Angeles to try to play again but speed was gone and his grip on the bat was affected by his numb left finger. His life was already in disarray. During his time in Vietnam, his mother could no longer pay for their Garden Grove house, and the bank foreclosed. There was bitterness in that situation as well. He had been the sole supporter of his mother and sisters –his father “went out to make a phone call” when Gleason was in junior high school and never came back. Gleason had been given 3A draft status, pretty much guaranteeing he would not be called to military duty. But he was.

He came back to the Dodgers’ farm system in 1969 and ’70, but war injuries and the results of a car accident that finally put an end to his baseball dream.

Over the years, Gleason worked in Orange County was a car salesman and as a bartender — including at Don Drysdale’s Dugout establishment in Santa Ana. He had two sons. He was living in a motor home.

The Dodgers replaced his lost World Series ring in 2003, giving a replica in a pre-game ceremony.

More than 3.4 million American military personnel were sent to Southeast Asia during the Vietnam War. Only one of them — Roy Gleason — had played major league baseball. Gleason remains the only U.S. combat veteran and former MLB player to receive “Special Congressional Recognition.”

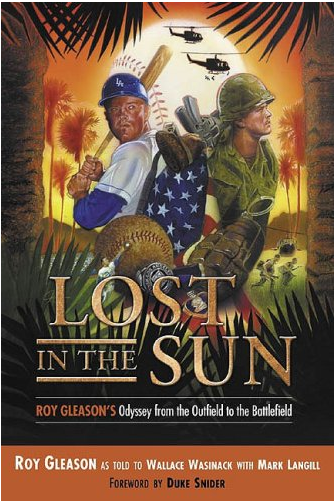

There’s far more in his book, “Lost in the Sun: Roy Gleason — Odyssey from the Outfield to the Battle Field,” with Wally Wasniak and Mark Langill.

For the next 34 years, Gleason felt himself fading away. He married twice, raised two sons and worked various jobs — bartending, moving furniture, and finally as a car salesman. He has recently retired but, as Plaschke noted, felt that he’d lived an unfulfilled life.

“I think he originally thought his life was a waste,” said Wasinack, who brought Gleason’s story to the attention of Langill, the Dodgers historian who arranged for Gleason to visit Dodger Stadium to meet with team officials and media.

“They all recognized him right away,” Langill told ESPN.com. “He’d been such a top prospect that both the old scouts and broadcasters knew who he was and reminded him of his days as a player.”

Dodgers broadcaster Vin Scully was so intrigued with what happened to Gleason that he devoted an entire pre-game show to his story. After Gleason threw out the ceremonial first pitch in 2003, it was Scully, part of the pre-game ceremony, who informed him that he was needed back at home plate to receive his ring replica.

Gleason says he “only one of thousands who were sent so far away from home, to that place none of us wanted to go and that place where many never left and that place where we were all lost in the sun.”

“A lot of people who read about it say my life is a sad story,” Gleason says. “But I can’t complain. I’ve had a better life than most.”

On the wall of the two-bedroom Temecula apartment Gleason shares with one of his sons are pictures from the ceremonies welcoming him to both Dodger Stadium and Petco Park in San Diego. In his closet hangs an army uniform, its creases as crisp as that day long ago when Gleason left Vietnam.

But Gleason, like many who served, will probably never really leave Vietnam until they are, at long last, welcomed back by the country that sent them all, as very young men a long time ago, off to fight.

“They deserve to be recognized,” Wasinack said. “They deserve to be welcomed home.”

Read more as well in this fantastic SABR.com biography.

Who else wore No. 36 in SoCal sports history?

Make a case for:

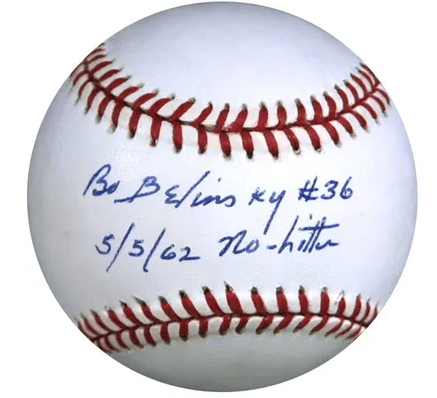

Bo Belinsky: Los Angeles Angels pitcher (1962 to ’64):

The headline with an exclamation point across the Long Beach Independent sports section on Aug. 15, 1964 read like something out of the 1919 Black Sox Scandal. Say it ain’t so, Bo.

Robert Belinsky, nicknamed Bo for the middleweight boxer Bobo Olson as a way to acknowledge his admiration of street brawling, was, and wasn’t, everyone’s favorite beau.

But when the Los Angeles Angels’ devilish starting pitcher had a run-in with a Los Angeles Times scribe, and all the other newspapers had to report — something. Newspapers, as the first draft of history, can also be conflicted in their storytelling. This report in the Independent was somewhat independent of the Times own version of events by the dear brave writer, Braven Dyer. But who’s to say who was telling the truth with self-preservation embellishments.

Already known for drinking, partying, and womanizing, New York-raised Belinsky came to the Angels as a rookie in 1962 after five seasons in the Pittsburgh and Baltimore organizations. He actually had a contract holdout, then posted 31 starts, lead the league in walks, and came away with a 10-11 record.

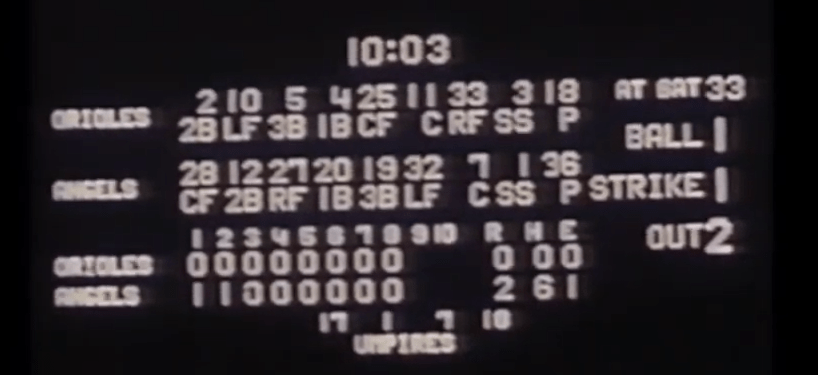

But during that time, Belinsky would famously throw a no-hitter against his former team, the Orioles, in just his fourth big-league start. There were just about 15,000 at Dodger Stadium/Chavez Ravine to see it. Which made him the first player to throw a no-hitter on the West Coast, the first to throw one for the two-year-old Angels, and, before Sandy Koufax, the first to turn the feat at Dodger Stadium. That also improved his record to 4-0 and he’d win six of his first seven starts.

“Hollywood … is gaga over Bo,” gushed the aforementioned Dyer.

On the mound, Belinsky once said: “My only regret is that I can’t sit in the stands and watch myself pitch,” according to the lead of his SABR.bio.

Angels owner Gene Autry gave Belinsky a $2,500 bonus and a cherry red Cadillac after the no-hitter. Then came the dames.

Ann-Margret, Tina Louise, Juliet Prowse and Connie Stevens were the headliners, and there was a highly publicized engagement to Mamie Van Doren. Belinsky would eventually marry Jo Collins, Playboy’s 1965 Playmate of the Year, and later become the husband of newspaper heiress Janie Weyerhaeuser. A son, Don Carroll, born out of wedlock in 1963, eventually happened — and he didn’t know his father until he was already in his 20s.

Bo Bellinsky takes a wistful look at a photo of his intended, actress Mamie Van Doren, at his hotel room during spring training. The couple confirmed they are engaged. Van Doren, 30, married twice before, and Bellinsky, 26, have been dating frequently. As it turned out the engagement didn’t lead to a wedding. (Photo: Getty Images).

Now it’s 1964. Belinsky is back at 9-9 with a 2.84 ERA, four complete games in 23 starts, and instead of punching out hitters, he’s punching a sportswriter. The accounts of of what happened at 2:30 a.m. in a Washington hotel:

“I tried to push him away. He fell and hit his head,” Belinsky said at first, then would add: “He reached for something in my attache case before I pushed him.”

(Angels manager Bill) Rigney and Angel trainer Freddie Frederico rushed to Belinsky’s room where “we found Braven unconscious.” The pair called Washington Senators team physician George Resta, who took Dyer to the hospital for treatment.

By chance, Belinsky’s roommate, Dean Chance, reportedly was taking a shower at the time of the incident and did not witness it.

Dyer and Belinsky had not been on friendly terms since February of 1962 when Belinsky, and Chance, failed to show up for a baseball writers dinner in Los Angeles, of which Dyer was the chairman.

The incident was prompted by a Dyer story, quoting Belinsky as saying he was misquoted about quitting baseball. Dyer was following up a national wire service story some hours earlier which had quoted Bo as saying he definitely would quit. Dyer said that the controversial Angel southpaw phoned him about 2 a.m. Friday to ask if the story had been sent (to Los Angeles). Dyer said that he had filed it. According to Dyer, Belinsky then said that he wasn’t misquoted, and told the writer, Belinsky then complained about mistreatment by newspapers, Dyer said, and ended by saying, “You come down here and I’ll stick your….. head under the shower.”

Dyer instead went to the room trying to fix things. He was met with punches to the eye and head, Dyer said. One of the blows toppled 64-year-old newsman and, in falling, his head hit the wall, bloodying his left eye. So there you go.

Belinsky refused a demotion to the minor leagues and was eventually banished to the National League, traded that ’64 off season to Philadelphia for a far-more reliable Rudy May (and a backup first baseman named Costen Shockley). Belinsky won only seven more games against 23 losses. He was done at age 33, but tried another year in the minor leagues until he was done in ’68.

Belinsky’s name often comes up when there’s the usual list of baseball cautionary tales, especially after a rookie pitcher does something noteworthy. Like when the Angels’ Reid Detmers threw a no-hitter in May of 2022. By June, he was back at Triple-A Salt Lake City. ThroneberryField.com did a nice post on looking at the previous 24 rookies who threw no-hitters, and what became of them. When it circled around to Belinsky, this was the writeup:

“The rakish Belinsky sent Hollywood wild when his fourth major league start and win was his no-hitter … It was the high point of a career to be eroded by too much taste for the demimonde and the high life.”

It also included a snipped of a 1972 profile by Sports Illustrated’s Pat Jordan, headlined “Once He Was An Angel,” with this assessment: “His name would become synonymous with a lifestyle that was cool and slick and dazzling, one that was to be a trademark of those athletes who appeared later in the ’60s — Joe Namath, Ken Harrelson, Derek Sanderson. But, in time, the name Belinsky would mean something else. It would become synonymous with dissipated talent.”

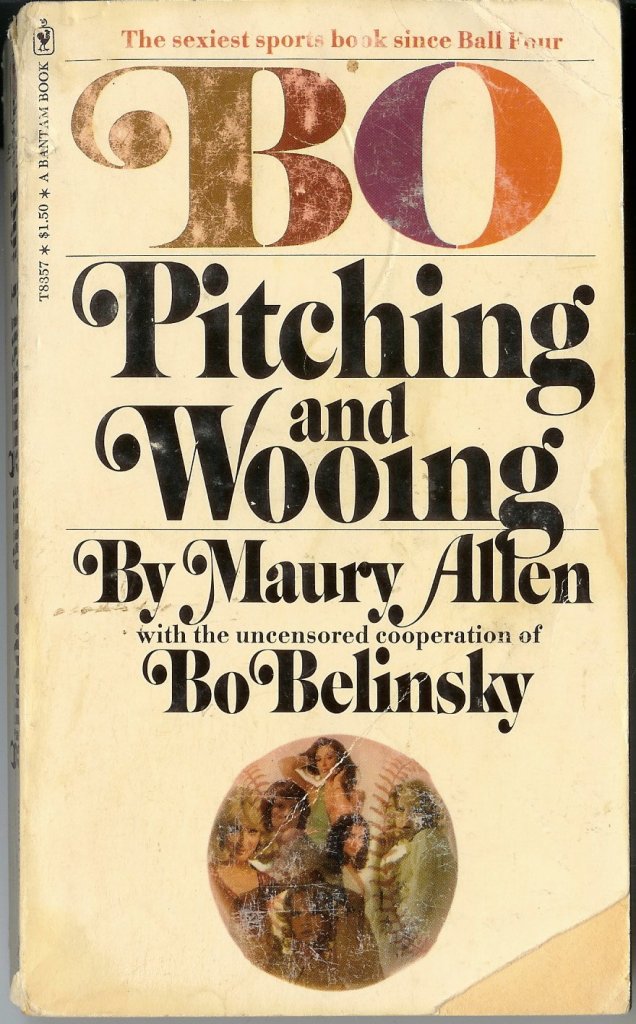

In 1973, he decided he needed to try to outdo Jim Bouton and “Ball Four” and wrote a book with Maury Allen called “Bo: Pitching and Wooing.” Belinsky was given credit as providing “uncensored cooperation.” It was also marketed as “the sexiest sports book since ‘Ball Four’.” Sports collector Bob Lemke on his blog said he once read the book and “I remember it as more self-aggrandizing than inside baseball. It might be worth a re-read today.”

Chris Foster wrote for the L.A. Times in 1992 about going to Las Vegas to track Belinsky down to see what a “somewhat normal life” looked like in his terms. “A lot of people are surprised to see me now,” the 56-year-old Belinsky said. “They come looking for one thing, and they sort of find another. I don’t have to take the responsibility of being the Great Bo Belinsky anymore. The world functions just fine without him.”

Belinsky died at 64 in 2001. In his New York Times obituary, Van Doren was quoted: ”Our life was a circus. We were engaged on April Fool’s Day and broke the engagement on Halloween. It was a wild ride, but a lot of fun.”

Jered Weaver, Long Beach State pitcher (2002 to ’04); Los Angeles Angels pitcher (2007 to 2016):

Coming out of Simi Valley High and Long Beach State (where he was national player of the year, also sported No. 36 and had it retired as the first in Dirtbags’ history), Weaver was the Angels’ first-round draft pick in 2004. When he was called up from the minor leagues early in the 2006 season, he wearing No. 56 — because his older brother, Jeff, had claimed the No. 36 he wore for several years when he joined the Angels that season. But funny thing: The roster spot for Jered opened when the team designated Jeff for assignment. Jered went on to post an 11-2 mark and 2.56 ERA in 19 starts that first season, switched to No. 36 for his second season, and eventually became a three-time AL All-Star selection (2010, ’11 and ’12, during which he was in the Top 5 of Cy Young voting each time). He led the AL in wins (20 in ’12 and 18 in ’14) and strike outs (233 in ’10). That earned him a sizable contract extension of five years and $85 million in August of 2011, making him the highest-paid pitcher in franchise history. He posted 150 wins with the Angels (and none with San Diego in his final year of 2017).

Jeff Weaver, Los Angeles Dodgers pitcher (2004 to 2005, 2009 to 2010), Los Angeles Angels pitcher (2006):

Six years older than Jered Weaver, the Northridge born and Simi Valley High standout had his MLB start with Detroit and the New York Yankees before coming back to Southern California — first with the Dodgers. He also ended his career with the Dodgers as a relief pitcher and spot starter. That one season with the Angels wasn’t all that special — a 3-10 mark (almost the opposite of Jered) with a 6.29 ERA in 16 starts before he sent down and dealt to St. Louis at the trade deadline.

Ramon Ortiz, Anaheim Angels pitcher (1999 to 2004): The default winner in World Series Game 3 for the Angels during their 2002 title run (despite giving up four runs in five innings, including a homer to Barry Bonds, of an eventual 10-4 win), he posted 13 wins in ’01, 15 in ’02 and 16 in ’03. Eventually traded to Cincinnati for a Double-A pitcher in ’04. Ended up wearing No. 35 for a season with the Los Angeles Dodgers in 16 games during a 2010 comeback.

Steve Bilko, Los Angeles Dodgers first baseman (1958): Back and forth between the Pacific Coast League and Major League Baseball, Bilko made his one-and-only Dodgers appearance for 47 games in their first year in L.A., hitting 11 homers in 188 at bats. That number only became available because of …

Don Newcombe, Los Angeles Dodgers pitcher (1958): He brought No. 36 with him to L.A. from Brooklyn, which Newcome wore it from 1948 through 1957, capturing an NL Cy Young and Rookie of the Year Award along with four All Star selections. Unfortunately, Newk made it through just 11 games in ’58, going 0-6 with a 7.86 ERA before he was traded to Cincinnati in a deal that included Bilko coming to L.A. and assuming that jersey number.

Frank Robinson, Los Angeles Dodgers outfielder (1972): During his MVP seasons with the Cincinnati Reds and Baltimore Orioles, and later during his stops in Anaheim and Cleveland, the 11-time All Star wore No. 20. Coming off a season in Baltimore where he was third in AL MVP voting and made his third All Star team in a row, Robinson was sent with reliever Pete Richert to the Dodgers for Doyle Alexander, Bob O’Brien, Sergio Robles and Royle Stillman. No. 20 wasn’t available — it had been spoken for by Don Sutton. So why was Robinson handed No. 36? Even the Dodgers’ team historians aren’t sure. Maybe it was a tribute to Don Newcombe — a number still not retired? Likely, it was the age Robinson turned that season? Effectively replacing Richie Allen in the Dodgers’ lineup as their menacing long-ball hitter, Robinson had a career-low. 251 with 19 homers and 59 RBIs. The next offseason he was sent the Angels (where he could get No. 20 again) in a trade that included Bill Singer, Bobby Valentina, Billy Grabarkewitz and Mike Strahler to the Angels for Andy Messersmith and Ken McMullen.

Jerome Bettis, Los Angeles Rams running back (1993 to 1995): Before he retired as the NFL’s fifth all-time leading rusher with 13,662 yards and 10 seasons in Pittsburgh leading to a Pro Football Hall of Fame status, “The Bus” was the Associated Press Rookie of the Year in ’93 and a Pro Bowl running back in ’94 during his age 21 and 22 seasons with the Rams in Los Angeles prior to their move to St. Louis (where he also had one more year with the franchise and was then traded to the Steelers. He had nearly 2,500 yards rushing in his two L.A. seasons with 10 touchdowns.

John Gibson, Anaheim Ducks goalie (2013-14 to present): Closing in on 200 career wins in his 11th NHL season, all in Anaheim. He was a 2015-16 Jennings winner (with Frederik Andersen) for having allowed the fewest goals by a team in the regular season (where he was 21-13 in 40 games at age 22).

Have you heard this story:

Nick Pasquale, UCLA football wide receiver (2012-2013):

A 5-foot-7, 172-pound walk-on freshman nicknamed “Pacman” from San Clemente who was an All-County defensive back/wide receiver in high school was 20 years old and had just played in his first game, the Bruins’ 58-20 season opening win against Nevada on Aug. 31. A week later, while was visiting his hometown during a bye week, he was hit by a car and killed. His death has become a rallying point for the nationally-ranked Bruins that season, as players wore a No. 36 patch on their jerseys. A foundation was established in his memory. Prior to the 2024 college football season, new head DeShaun Foster said redshirt senior defensive back Joshua Swift would wear No. 36 in honor of Pasquale. “The way (Swift) approaches the game, we wanted (the person wearing No. 36) to be a potential walk-on who can try to win a scholarship and just exudes what being a Bruin is — discipline, respect and enthusiasm,” Foster said. Swift saw his first playing team in the 2021 season and was later awarded the Nick “Pac” Pasquale Memorial Award for Special Teams Scout Team Player of the Year at the annual team banquet. Before Swift, the previous two Bruins to wear No. 36 were defensive back Alex Johnson (2022-23) and wide receiver/running back Ethan Fernea (2019-21). In 2025, redshirt sophomore linebacker Wyatt Mosier wore No. 36.

Ramogi Huma, UCLA football linebacker (1995 to 1997):

Growing up in Covina anda standout at Bishop Amat La Puente High, Huma told the UCLA alumni magazine he had been “recruited by pretty much every Pac-10 school in the nation” but picked UCLA largely to remain close to his mother. “It wasn’t long before some things opened my eyes to how college sports works,” he said. Teammate Donnie Edwards was allegedly given groceries by a sports agent, it went public and the NCAA suspended the star linebacker for one game and made him donate $150 to charity to cover the cost of the groceries. Huma, then a freshman, couldn’t believe a college athlete could be punished over food. In 1997, Huma and teammate Ryan Roques founded the Collegiate Athletes Coalition, a campus-recognized student group to pushing an agenda of specific reforms related to the welfare of student-athletes. Though a hip injury ended Huma’s playing career a year later, he remained in school to earn a master’s degree in public health. He realized the embryonic pro-athlete movement couldn’t survive without being attached to an existing organization. Eventually, he founded and became the executive director of the nonprofit National College Players Assn., working from home in Eastvale near Riverside. He testified at U.S. Congressional hearings about college student athletes’ rights, helped Northwestern players fight for unionization in 2014 and has been a voice in the Name, Image and Likeness movement in college football’s timeline.

Fernando Valenzuela, California Angels pitcher (1991): When the Dodgers released him in 1991 spring training, the Angels eventually figured he could be a possible draw for crowds. It was very short lived. Valenzuela couldn’t get his usual No. 34 because the Angels’ Bryan Harvey had it. Valenzuela couldn’t get much on his screwball, either. He made just two starts in early June, lost both, gave up five runs in each, and had himself a a 12.14 ERA. After that ended, he spent 1992 pitching in Mexico before giving the MLB one more try — Baltimore, Philadelphia, San Diego and St. Louis, retiring at age 36.

Caden Dana, Los Angeles Angels pitcher (2024): At 20 years, 259 days old, Dana became the youngest Angels in team history to win a game and the youngest starter since Frank Tanana in 1973 when he lasted six innings, giving up two runs to Seattle on Sept. 1 after his call up from the Double-A Rocket City Trash Pandas. The 6-foor-4 lefthander is also the first pitcher in MLB history with the first name “Caden.”

Oliver Drake, Los Angeles Angels pitcher (2018): Only two pitchers in MLB history pitched for five teams in one season. Drake was one of them. His 2018 season started in Milwaukee and Cleveland, and finished in Toronto and Minnesota. In between, the Angels had him from June 1 to July 21: Eight appearances, 8 2/3 innings, 0-1 record, 5.19 ERA. The only other player to appear with five teams in one season: Mike Baumann, in 2024, and the Angels were one of them, as he wore No. 53.

Lefty Phillips, California Angels manager (1969 to 1971): Harold Ross Phillips, out of L.A.’s Franklin High, had trouble with his left pitching arm while in the low minor leagues, decided to become an MLB scout, and ended up as the one to sign Don Drysdale to a pro deal with the Dodgers. Phillips then was Walter Alston’s pitching coach for the Dodgers from 1965 through ’68 before the Angels hired him away for their front office as director of player personnel. When Angels manager Bill Rigney started the ’69 season with an 11-28 mark, Phillips was promoted to skipper — just the second in franchise history. Phillips’ overall 222–225 record saw third-place finishes in the AL West in ’70 and ’71. He went back to scouting but died in June of ’72 from a fatal asthma attack at age 53.

Edwin Jackson, Los Angeles Dodgers (2003 to 2005): The man with the Twitter account of @EJ36 did not play for 36 MLB teams. Just 14. Which is the most by an MLB player in history. One of the best default names to use when playing the “Immaculate Grid” game on the Internet started his journey as a 19-year old in September of ’03 when the Dodgers sent him out in a game at Arizona matched up against 39-year-old Randy Johnson. Turned out, Jackson was the winning pitcher in a 4-1 Dodgers victory, and Johnson took the loss. Traded to Tampa Bay prior to the 2006 season, Jackson added Detroit (making the AL All Star team in 2009), Arizona, the Chicago White Sox, St. Louis, Washington, the Chicago Cubs (leading the NL with 18 losses in 2013), Atlanta, Miami, San Diego, Baltimore, Washington (again), Oakland, Toronto and Detroit (again) before he retired at age 35 in 2019. In amassing the most different MLB uniforms (he was not the most traded player), Jackson also wore No. 22 (in ’04) and No. 58 (in ’05) for the Dodgers before taking on No. 36, which he also had for seven teams.

Special recognition:

Jason Ochart, Director of Hitting Development and Program Design, Boston Red Sox:

As the Boston Red Sox specialized hitting coach since 2022, Ochart wears No. 36. It is in honor of his late Hoover High school baseball coach, Jim Deizell. How Ochart got to this place is a sign of where the MLB is in this time and place. Between 2007 and 2013, Ochart wore No. 7 at Hoover High in Glendale, then Glendale Community College, and eventually Vanguard University in Costa Mesa as a pitcher and infielder. The Driveline Baseball Enterprises hired him as a director in 2016, promoted to special assistant in 2020. He was hired as the Philadelphia Phillies’ minor league hitting coordinator from 2018 to 2022. A 2019 story in the Sports Business Journal under the headline “Keepers of the Batting Cage: How Outsiders Became the Ultimate MLB Insiders,” Ochart admits he was “turned into a pitcher because I was such a bad hitter. I started to wonder why I was so bad. I think it’s a pretty common story when you talk to these new-age hitting coaches. A lot of them hit rock-bottom early as players, so they started asking questions. I was certainly one of those guys.” Ochart earned a degree in kinesiology from Vanguard and worked on video breakdown of the baseball swing, shared his findings on Twitter while coaching at Menlo College, and caught the eye of Driveline Baseball, a training facility in Seattle. In Jane Leavy’s 2025 book, “Make Me Commissioner,” Ochart is one of the prime sources interviewed in how the game has changed.

We also have:

Greg Maddux, Los Angeles Dodgers pitcher (2006 and 2008): En route to the Baseball Hall of Fame, he posted a 6-3 and 3.30 mark at the end of ’06 at age 40, then 2-4 with a 5.09 ERA at the end of ’08 at age 42.

Lefty Phillips, California Angels manager (1969 to 1971): A 222-225 record. And one tie.

Rick Rhoden, Los Angeles Dodgers pitcher (1974 to 1978)

Todd Ewen, Mighty Ducks of Anaheim right wing (1993-94 to 1995-96)

Dick Harris, Los Angeles Chargers defensive back (1960)

Marcus Smart, Los Angeles Lakers guard (2025-26)

Anyone else worth nominating?

2 thoughts on “No. 36: Roy Gleason”