This is the latest post for an ongoing media project — SoCal Sports History 101: The Prime Numbers from 00 to 99 that Uniformly, Uniquely and Unapologetically Reveal The Narrative of Our Region’s Athletic Heritage. Pick a number and highlight an athlete — person, place or thing — most obviously connected to it by fame and fortune, someone who isn’t so obvious, and then take a deeper dive into the most interesting story tied to it. It’s a combination of star power, achievement, longevity, notoriety, and, above all, what makes that athlete so Southern California. Quirkiness and notoriety factor in. And it should open itself to more discussion and debate — which is what sports is best at doing.

The most obvious choices for No. 62:

= Bill Bain: USC football; Los Angeles Rams

= Al Krueger: USC football, Los Angels Dons

The most interesting story for No. 62:

Brent Boyd, UCLA football offensive lineman (1975 to 1979) via La Habra

Southern California map pinpoints:

Downey, La Habra, Whittier, Westwood, Pasadena

Brent Boyd’s brain, bruised and battered, had finally betrayed him.

Headaches and memory loss. Dizziness and fatigue. MRIs and other medical tests couldn’t pinpoint what would be the early onset of dementia. That all came after a six-year run as an NFL offensive lineman — which, to the 6-foot-3, 286-pounder out of UCLA — felt like a lifetime ago.

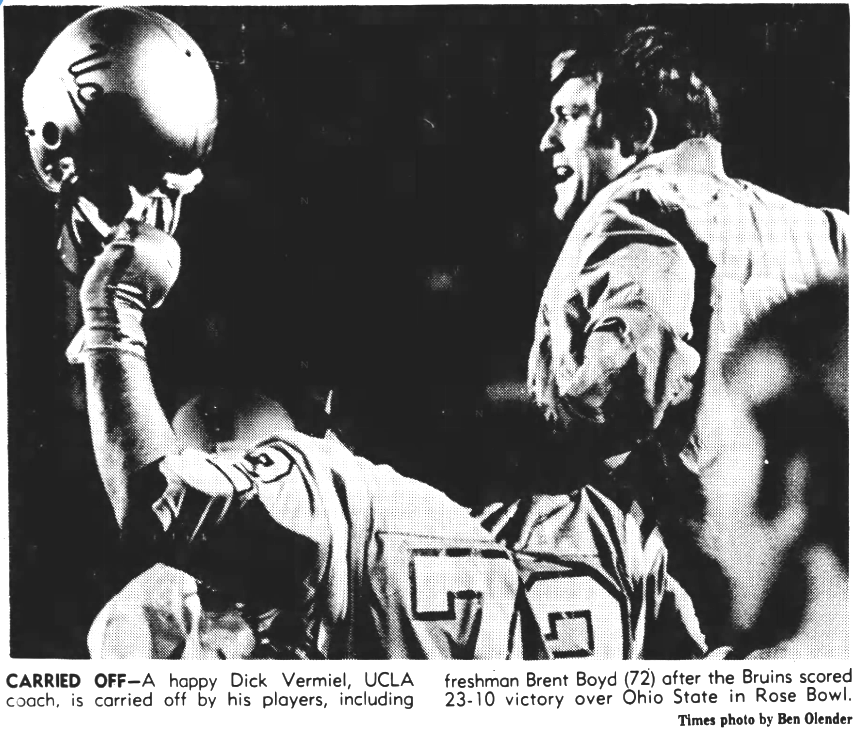

Born in Downey and reared in La Habra, Boyd doesn’t think anything serious happened to him under the helmet as he learned the game at Lowell High in Whittier. He couldn’t recall any traumatic experiences during the four years he put in at UCLA, a career that started as a member of the 1976 Rose Bowl championship team and ended with him second-team All-Pac-10. He caught the attention of the Minnesota Vikings to make him a third-round NFL pick.

Wearing No. 62 as a 23-year-old rookie offensive lineman, trying to make a living as in pro football after forgoing a chance to go to graduate school at UCLA, Boyd got an on-the-job education about what a concussion felt like. Over and over.

Especially in how it was addressed and treated. Or wasn’t.

Boyd once explained his first experience during in the Vikings’ final exhibition game against Miami at the Orange Bowl:

“In the second quarter I got hit, knocked out. My teammates carried me to the sidelines and when I woke up, I was blind in my right eye. I started to panic.

“My coach came over and said, ‘Boyd, what’s the matter?’ I was still panicking and I said, ‘Coach I can’t see out of my right eye.’ And he said, ‘Well, can you see out of your left eye?’ And I said, ‘Well, yeah.’ And he said, ‘Get back in the game right now’.

“I had to finish the game unable to see out of my right eye. That situation was common.”

Boyd told that story, and many more personal experiences, during three appearances before U.S. Congressional committing hearings in Washington D.C. The televised events tried to get some answers about the NFL and brain injuries.

Boyd became Exhibit A for chronic traumatic encephalopathy — better known as CTE. His platform was as the founder of the NFL retired players advocacy group, Dignity After Football. It has become his LinkedIn professional title.

“Going into the NFL,” Boyd would say, “we knew we were going to play through pain, wind up as old men with bad knees, shoulders, other body parts. It was a risk, but we made an educated calculation and decided to play professional football. If I knew then what I know now, I wouldn’t have played.”

The first and only time Brent Boyd got mentioned in Sports Illustrated, it had to do with an injury.

In the 1978 college football preview issue, during an assessment of UCLA’s chances in the Pac-10, the story reported that “the blocking up front would be stronger had center Brent Boyd not broken a bone in his foot in spring practice, one of several serious spring injuries. Boyd, who has already had one operation, is probably out for the season. Sophomore Larry Lee moves from guard to replace him.”

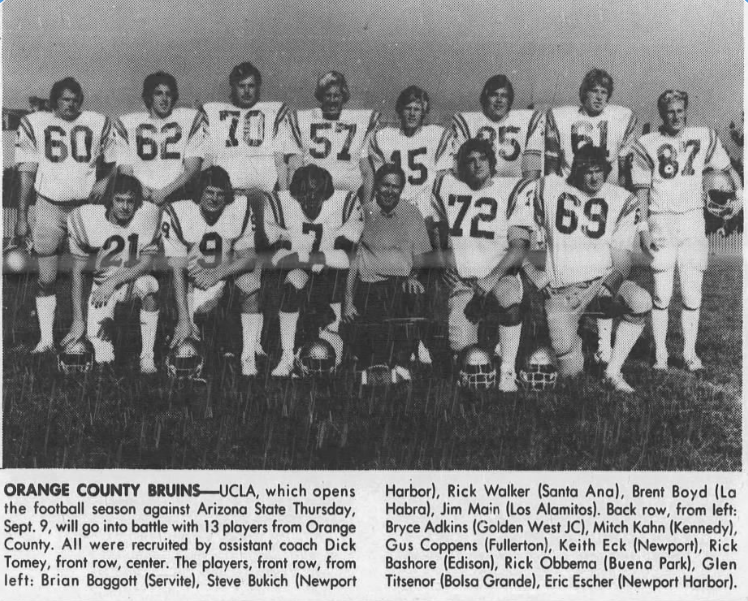

UCLA head coach Dick Vermeil came upon Boyd while scouting an other player at a high school game in the mid-’70s. Vermeil tipped off his top Orange County recruiter, Dick Tomey, to investigate more.

Boyd had a history of foot injuries as a prep sophomore and junior and hadn’t been recruited much by his season season. His plan was so go play at Fullerton Junior College, then perhaps catch on at Cal State Fullerton. But as teams like UCLA started to size him up, Boyd saw opportunities.

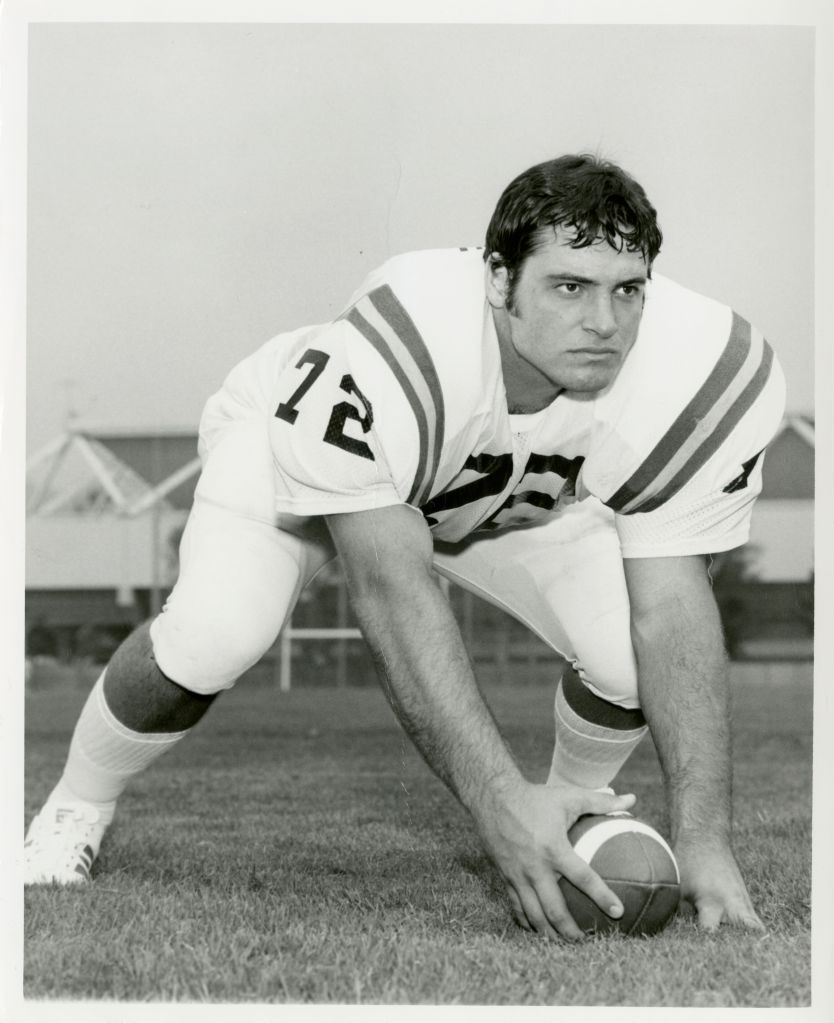

A sociology major who wanted to major in journalism but the program was dropped when he arrived, Boyd wore No. 72 as a starting defensive right tackle for Vermeil in 1975.

When Vermeil left, new UCLA head coach Terry Donahue flipped Boyd to the offensive line, as a guard. The next spring, Boyd moved over to center. Donahue’s offense was transiting from the Veer to the I-formation and it required the line, which included standouts such as Max Montoya, Luis Sharpe, Dan Dufour and Bruce Davis, to hold their blocks longer so holes could open up for the likes Freeman McNeil and Theotis Brown.

All the position changes had Boyd considering transferring out of Westwood. His roommate, Jim Main, wouldn’t let him do it.

“Things were going downhill and I felt like a has-been already,” said Boyd in 1977. “Jim talked me out of leaving. He didn’t even letter as a freshman but he said we both had to stick it out.”

In November of ’78, Boyd may have thought he made the right move — he was named first-team center on the United Press International All-Coast team. But remember what SI had reported? Boyd hadn’t played that season because of the broken foot, which was encased in a cast for six months.

“Well I’m not going to argue with them,” Boyd said when he heard about it. “I didn’t make a mistake all season. I didn’t miss a block.”

The wire service was finally informed of its error and dropped Boyd from the list.

“It’s hard for an offensive lineman to get any publicity as it is,” Boyd laughed when asked about it in September of 1979.

By the time Boyd graduated with All-Conference second-team recognition, he considered staying at UCLA to pursue a law degree. Minnesota Vikings head coach Bud Grant and his staff headed up the North squad in the 1980 Senior Bowl months before the NFL Draft. Grant met Boyd, new he played center at UCLA, but wanted to see how he fared at offensive guard and tackle.

“We were impressed with his intelligence,” said Grant. “When our turn came up in the third round, we selected him because he was not only the best player available but we knew he was a responsible person who we could count on.”

Boyd’s 4.9 speed in the 40-yard dash was also pretty good for someone his size. He was smart and adaptable. The NFL seemed to be the better payoff.

In Week 6 of Boyd’s rookie year, after a Vikings’ 13-7 win over Chicago, Grant gave Boyd one of the game balls. The team’s offensive line was banged up, including All-Pro Ron Yary who played through it. Boyd stepped in and took over for starting guard Jim Hough.

Boyd pulled off the play of the game — Chicago’s Gary Fencik had recovered a fumble and was returning it for what looked like a sure touchdown. Fencik made it 52 yards down the field with two blockers in front of him. Boyd ran him down and knocked him out of bounds at the 19 yard line.

“At first I didn’t realize Tucker fumbled the ball,” Boyd said. “My view was blocked. I started to run when I saw the official trailing Fencik. I knew I had to get in front of the two blockers. Once I got in front, I felt I could either knock him out of bounds or that one of the blockers would clip me. I never expected to get as good a shot as I did.”

One of the other aspects of Boyd’s performance that wasn’t lost on Grant — Alan Page, the eventual Hall of Fame All-Pro defensive tackle who made his career in Minnesota but was now playing for the Bears, wasn’t able to add to his league-leading sack total because of Boyd’s presence on the Vikings’ line blocking him out.

“It was an experience blocking a legend like Page,” Boyd said. “If you come off the ball slowly he will beat you and make you look bad. On one of our field goal tries, he really came hard. But I kept in front of him.”

Boyd made the NFL’s All-Rookie team in 1980, starting nine of 16 games. In one late December game as the Vikings were trying to make the playoffs, a bold comment he made in the huddle was captured by the media and displayed his sense of humor. As a Week 15 game against Cleveland was winding down, the Vikings, who already put together an impressive fourth quarter rally to get close, had one play left with four seconds to go. Boyd reportedly said: “Hey, Mad, why don’t you make one of those catches like we see in the highlight films.”

Boyd was addressing Vikings star receiver Ahmad Rashad.

“I’ve been thinking about it,” Rashad answered.

Rashad then caught, with one hand, a 46-yard bomb from Tommy Kramer on a Browns deflection that provided a 28-23 win.

In a career primarily blocking for Vikings quarterback Tommy Kramer, Boyd logged 59 games played over seven seasons, missing all of 1984. Before his second season, Boyd blew out his left knee out during a September, 1981 practice after a teammate fell on him. Boyd came back to start the last three games.

The 1982 NFL strike/lockout resulted in only four games played that season. He came back in ’85 to start 14 of 15 games.

But in 1986, Boyd was released after five games by new head coach Jerry Burns, unable to come back with multiple injuries that included a broken leg.

Boyd tried to segue into retirement. His head wasn’t following his heart.

He tried selling insurance, and then beer. He couldn’t keep any of the jobs.

“Instead of seeing accounts, I’d have to pull off the road and take a nap,” Boyd recalled. “I just couldn’t handle the work load, the whole time not knowing the reason. … My family asked, ‘What the hell happened to you, you were so motivated and now you can’t hold down any job and you just want to sleep the whole time?'”

He became a single dad. He went in and out of homelessness. None of this made sense to him why he was not able to keep things straight.

“You know, I had such big plans and had graduated with honors from UCLA and at that time I think everybody who knew me thought this guy is going to go on to big things after football, besides football. I just couldn’t,” Boyd said in an extensive 2007 ESPN story that for the first time explained his condition and situation of trying to have it diagnosed.

Sports agent Barry Axelrod got to know Boyd through a network of his UCLA alumni friends. He recalls how he and others in the social circle of former Bruins judged Boyd in the years that followed his NFL career as his marriage crumbled and his drinking increase.

“Brent had a lot of us scratching our heads,” said Axelrod. “He had been an overachiever, a hard-charging honor student, a clearly intelligent guy.” Axelrod said he friends came to think of him as “a lazy, no-account guy who couldn’t hold down a job.”

Boyd, who once told the L.A. Times that concussions in the NFL were treated “like a nuisance, like hitting your funny bone,” saw no one amused when, at age 50, he was asked to testify before Congress in June of 2007 about his experiences.

He was far less famous than several others who died before him, but Boyd was coherent enough to explain what he and others encountered.

Rep. Linda T. Sanchez, a Democrat from Lakewood and chairwoman of the House Judiciary Subcommittee on Commercial and Administrative Law, said she wanted the hearing to “shed some light on how the disability benefit process works for retired players, and to determine whether or not the system is unfairly stacked against them. The descriptions of how difficult it is to apply [for benefits], and how many years it takes to get benefits, seems to me to be a little excessive.”

Boyd, at that point, had a compelling narrative. He said he thought he had at least 200 concussions. Much of that was the result of playing so much on Astroturf, especially inside the Vikings’ Metrodome.

Boyd said he sought relief, but three NFL-picked doctors for him decided in 2001 that one particular concussion Boyd sustained “could not organically be responsible for all or even a major portion” of his condition. He was denied benefits of about $8,000 by a disability board as well as the players’ union and would have to accept the $1,500 the league offered.

Boyd saw all of this as a call to action.

As one of the first to speak up about this issue, try to change policy, and perhaps find some retribution for him and hundreds of others who’ve suffered from the injury while performing for the multi-billion-dollar organization, Boyd was not just on a self-help crusade, but saw the bigger picture. Even as the NFL and its players union pushed back.

NFLPA Executive Director Gene Upshaw didn’t seem to help Boyd’s pleas. Other retired players came to resent Boyd. They felt bringing all this up threatened their benefit payouts.

One of those who spoke out against Boyd was former Chicago Bears All-Pro safety Dave Duerson, who served on the NFL’s disability board. Deuerson eventually shot and killed himself at age 50, a CTE victim in 2011.

“I sincerely feel for their family’s loss,” Boyd would later say. “But they need to realize the suffering Duerson caused for other families.”

Others were there for him.

“It’s right versus wrong,” Mike Ditka, the Chicago Bears head coach and Hall of Fame tight end, said at the June ’07 proceedings. “It’s do the ethical thing or do the wrong thing. So far, they’ve chosen to do the wrong thing.”

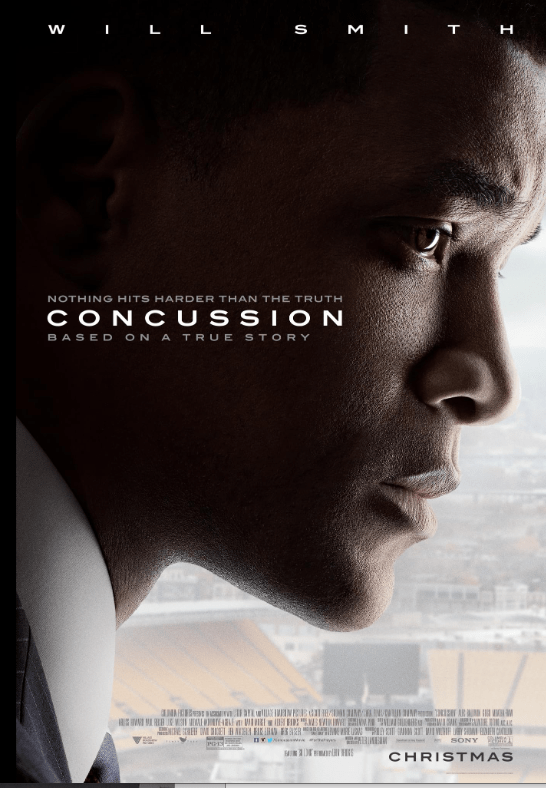

By the time the film “Concussion” came out in 2015, the general public was more in tune what had been happening to former NFL players more and more susceptible to brain injuries leading to very bad endings.

The film, starring Will Smith as the real-life forensic pathologist, showed how the first CTE diagnosis was former Pittsburgh Steelers star Mike Webster. After Webster’s death in 2002, the NFL tried to squash the evidence for many years.

The script for the film came from a GQ magazine story in 2009 called “Game Brain” by Jeanne Marie Laskas.

That story was accompanied by a unique, highly impactful 20-episode video series called “Casualties of the Gridiron,” which provided visuals and audio to further examine the crippling pain and drug addiction that came as a result of NFL head injuries.

Boyd was one of the first stories told in that GQ series. His piece was called “The Struggle with Brain Damage and Addiction.”

After feeling public relations pressure, the NFL in 2010 tried to appear to be more proactive about posting warnings about brain injuries — like the surgeon general’s warning about the dangers of cigarette smoking.

It replaced a pamphlet that had been issued since 2007 and tried to purport: “Current research with professional athletes has not shown that having more than one or two concussions leads to permanent problems if each injury is treated properly.” It also left open the question of “if there are any long-term effects of concussion in N.F.L. athletes.”

In 2013, the NFL reached a $765 million settlement agreement with a U.S. district court judge that was supposed to help some 4,500 players part of a class-action lawsuit. Boyd, one of the players who filed first and convinced others to join, called that amount “like throwing a pebble in the sea. Football caused this. Football has caused my quality of life to deteriorate.”

Boyd, then a 56-year-old Reno, Nev., resident, also told the Reno Gazette Journal: “For guys like me, and a lot of other guys I know, we are looking for more restitution. We’ve lost everything in our lives. We’ve lost ourselves, our personalities, our dreams and our memories.”

Boyd repeated something that summed up all the red tape he continued to deal with.

“I was talking about the NFL’s plan for disability and their strategy was ‘delay, deny and hope we die’,” said Boyd. “It seems like this settlement might be along the same lines. It sounds like they put some money out there but not enough and there’s no clear way for the players who need that money get access to it.”

Sadly, Boyd had another example how that NFL gameplan was working when former UCLA and Minnesota Vikings linebacker Fred McNeill was no longer able to help this cause.

McNeill, a Baldwin Park High ALL-CIF selection in football who also lettered in basketball and track, was first-team All-Pac 8 in both 1972 and 1973. He served as a team captain in 1973 and was selected as a first-team All-American following that season.

The Vikings took him as a first-round pick (17th overall) in 1974. As the 6-foot-2, 230-pounder was out of the NFL by 1985, having played in two Super Bowls for the Vikings and at one point started 102 consecutive games, McNeill got a law degree and joined a local firm with his son.

McNeill saw his induction into the UCLA Athletics Hall of Fame in 2012. But three years later he died in November, 2015 at age 63 after a battle with ALS. The disease was brought upon by his head injuries, proven when he tested positive for CTE in a pioneering UCLA study several years before his death.

McNeill was said to be the first person to have been diagnosed with CTE while alive and have it confirmed following his death by Dr. Bennet Omalu — the same pathologist who Will Smith played in the film “Concussion.” GQ documented his case in 2011.

McNeill’s wife, Tia, could at least speak on his behalf as the Vikings franchise was trying to reconcile how they had four players among the 111 who by that point had died from CTE, according to the Journal of the American Medical Association. One of them was Grant Feasel, a center for the Vikings from 1984 to ’86 during his nine-year NFL career and one of Boyd’s former teammates.

In 2016, Boyd saw how the NBA addressed its concussion issue with a lifetime health insurance policy for retired players. He wondered why the NFL couldn’t do the same.

“It’s like a slap in the face,” he said. “I have been so disappointed in our union. … and now we’re getting older and dying.”

By 2017, as Boyd continued to doubt he would get any substantial payout once the next NFL settlement filing period opened. Boyd wrote a first-person account of what he was still dealing with. He circled back to that first memory of a first concussion and tried to put it into perspective:

“Until we started raising awareness about concussions maybe 10 years ago … the culture of the NFL (was that) you play injured. … It’s reasonable to say that the guys who played in the 1960s, and 1970s could have had hundreds of concussions. I don’t think you can make too many more changes to the game of football; it’s never going to be safe. The helmets keep your head from getting cracked, they keep your nose from getting broken, but danger will always be there. Because of socio-economic reasons there will always be players willing to play the game.”

Online record-keeping supports several lists of those who’ve died in the NFL as a confirmed result of CTE since the first autopsies were performed in 2002. Some names that jump out — Frank Gifford, a one-time USC star and network broadcaster; Los Angeles Rams fullback Ollie Matson and running back Mosi Tatupu (USC); Los Angeles Raiders running back Wes Bender (Burroughs High in Burbank and USC); former Mater Dei High quarterback Colt Brennan; Baltimore Colts safety Nesby Glasgow (Gardena High); offensive lineman Max Tuerk (Santa Margarita High, USC) …. the list goes on and on.

CTE stories come up in the news, often without warning, sometimes with more Southern California connections.

Shane Tamura, a 27-year-old former player at Golden Valley High in Santa Clarita and Granada Hills High, had a documented history of mental health when he went on a deadly shooting rampage, killing four people in New York in July of 2025. He apparently thought he was attacking the NFL offices and appeared to have a grievance with the league’s handling of head trauma, but he ended up on the wrong floor of a skyscraper that houses the NFL headquarters.

He had a suicide note in his wallet alleging he suffered from CTE. “Study my brain, please,” the note said. They did, and it turned out to be accurate.

The event came days after The Athletic/New York Times ran an extensive feature about Greg Newman, a defensive tackle who last played football at the University of Utah, coming out of Westlake High School. He was found dead, having been homeless and living out of a motel, near an onramp at the 101 Freeway in Thousand Oaks in 2024. His family started a GoFundMe project to raise money so his brain, eyes and spinal cord could be donated to the Boston University CTE Center, which confirmed their assessment.

A 2024 study of nearly 2,000 former NFL players concluded that, while it’s not possible to confirm yet in a living person, one in three believe they have CTE. Myron Rolle, a former standout safety at Florida State who was drafted by the NFL’s Tennessee Titans but never played in a regular-season game, became a neurosurgeon after a residency at Harvard Medical School/Massachusetts General Hospital and is often an expert sought to talk about football-related CTE injuries.

Boyd has managed to stick around. He can give context on what this all means to him, the sport, and his fellow teammates. They would not settle for becoming collateral damage to the game’s fortunes.

“I’m just a guy nobody’s heard of,” Boyd once said. “But most of the guys who played in the NFL are like me, guys you’ve never heard of, and we’re hurting bad. We need help.”

Who else wore No. 62 in SoCal sports history? Make a case for:

Bill Bain: USC football offensive lineman (1972 to 1974), Los Angeles Rams offensive guard and tackle (1979 to 1985)

Out of St. Paul High School in Santa Fe Springs, the Los Angeles-born, 6-foot-4, 279 pounder came to USC after stops at San Diego City College and the University of Colorado to become an All-American offensive lineman, first-team All-Pac 8 in ’74 and part of the Trojans’ national title teams in ’72 and ‘74. A second-round NFL pick in 1975 by Green Bay, Bain’s 11 pro seasons included seven with the Los Angeles Rams as an All-Pro offensive tackle, playing 96 games as he was part of creating holes for Eric Dickerson. He started all 32 games in a row from ’83 to ’84 after a move to left tackle. There’s also the line that Los Angeles Times columnist Jim Murray once wrote: “Once, when an official dropped a flag and penalized the Rams for having 12 men on the field … two of them were Bain.”

Al Krueger: USC football end (1938 to 1940), Los Angeles Dons (1946):

The three-year varsity letterman was co-MVP of the 1939 Rose Bowl at the end of his first full season, catching four straight passes from fourth-string quarterback Doyle Nave (the other co-MVP) in the last two minutes, including a 19-yard game-winning touchdown, creating the final 7-3 verdict. “I had faded back to about the 31- or 32-yard line and, as soon as he made his move, I threw that damn thing as hard as I could right into the corner,” Nave told the LA Times in 1988. “And he was there.” Krueger, who had broken free from the Duke All-American Eric Tipton, hauled in the touchdown pass, the first Duke had given up all season. “On that touchdown play there was only one thing on my mind. That was that I’d better get down there in a hurry and not drop the ball,” Krueger was quoted by the United Press after the game. “I knew it would be there when I arrived. It always is when Doyle throws ’em.” The next year, Krueger’s touchdown catch helped ruin Tennessee’s perfect season in a 14-0 Trojans victory. “Antelope” Al, so-named because he came from Antelope Valley High after he was born in the city of Orange, was inducted into the Rose Bowl Hall of Fame in 1995. When Krueger left USC after the 1940 season, he played for the Washington Redskins for two years (making the Pro Bowl in ’42), then became a flight instructor in the Navy, returning to pro football briefly after World War II as an end with the Los Angeles Dons of the All-America Conference.

Have you heard this story:

Scot Shields, Anaheim/Los Angeles Angels of Anaheim pitcher (2001 to 2010):

A key bullpen contributor and innings-eater during the team’s 2002 World Series run (5-3 in the regular season with a 2.20 ERA), he pitched in 78, 74 and 71 games over the ’05, ’06 and ’07 seasons, in the AL top 10. He also pitched in six playoff series for he Angels (1-2, 3.20 ERA). He played all 10 of his MLB seasons with the Angels, piling up a 46-44 record and 3.18 ERA with 21 saves and 114 games finished. And why is first name spelled Scot, with one “t”? Because he said his mother didn’t want him to be named after a roll of toilet paper.

Anyone else worth nominating?

The Brent Boyd story provides great insight into what hundreds of NFL players have lived through.

LikeLike