This is the latest post for an ongoing media project — SoCal Sports History 101: The Prime Numbers from 00 to 99 that Uniformly, Uniquely and Unapologetically Reveal The Narrative of Our Region’s Athletic Heritage. Pick a number and highlight an athlete — person, place or thing — most obviously connected to it by fame and fortune, someone who isn’t so obvious, and then take a deeper dive into the most interesting story tied to it. It’s a combination of star power, achievement, longevity, notoriety, and, above all, what makes that athlete so Southern California. Quirkiness and notoriety factor in. And it should open itself to more discussion and debate — which is what sports is best at doing.

The most obvious choices for No. 97:

= Joey Bosa, Los Angeles Chargers

= Jeremy Roenick, Los Angeles Kings

= Joe Beimel, Los Angeles Dodgers

The most interesting story for No. 97:

Joe Beimel, Los Angeles Dodgers relief pitcher (2006 to 2008)

Southern California map pinpoints:

Los Angeles (Dodger Stadium bullpen), Torrance

What a relief it was in 2008 — Joe Beimel bamboozled the burgeoning business of baseball bobbleheads and brought it upon himself to rebrand his name, image and likeness to his liking.

Boom …

As something of a left-over in a world of left-handed middle relievers, Beimel had found a place in the Los Angeles Dodgers bullpen during the 2006 and ’07 season primarily as the guy who could be called upon to bind up NL West rival Barry Bonds when he came to the plate in a key situation. With that, Beimel somehow converted an under-the-radar, cool surfer vibe into ceramic folk-lore status.

His faithful followers actually forced the Dodgers to make good on a promotional campaign promise and create a bobble replica of him — free, for those who bought a ticket to a promoted game. That’s what the people wanted. Allegedly.

With all due respect, did everyone respect the process by which this happened, and can still live with its consequences?

Nod yes if you are in the affirmative.

The context

Once upon a time, a kitschy paper-mache souvenir that represented the game’s innocence in the 1960s began showing up. It often had a generic cherub face with a disturbing grin that kids could put on their shelves and be haunted by as its head bounced up and down on coils, brandishing the team’s colors and uniform.

By the late 1990s, the nostalgic craze for baseball of yesteryear was ignited when the San Francisco Giants tested out a Willie Mays bobble figurine, and 35,000 were given away in a 1999 game.

The Dodgers, of course, couldn’t watch the giant promotional opportunity pass them by.

By 2001, the Dodgers ramped up their first offerings as a fan giveaway — Tommy Lasorda, Kirk Gibson and Fernando Valenzuela were the first three created. Dodgers broadcaster Vin Scully quipped the Gibson bobblehead looked more like actor Stacy Keach.

From there, the Dodgers and their China-made bobbleheads came as a steady flow. When they expanded to four giveaways in 2007, fans were allowed to pick one to create through an Internet vote. Catcher Russell Martin was the first “winner.”

In spring training of 2008, the team announced plans for bobblehead nights recognizing incoming manager Joe Torre and All-Star pitcher Takashi Saito. Now there were two spots up for grabs for the voters. The likely candidates were Matt Kemp and Andre Ethier. Maybe Nomar Garciaparra or newly acquired Andruw Jones. Clayton Kershaw was just a 20-year-old unproven rookie. Manny Ramirez wouldn’t barge into the spotlight until months later.

Beimel, a 6-foot-3, scruffy long-haired guy from Pennsylvania came into town a couple years earlier with baggy pants to go with a baggy uniform. Given No. 97, it was, at the time, the highest number ever used by a Dodger going back to the 1930s. Beimel said 97 represented the birth year of his son Drew, his first child.

Pittsburgh made Beimel an 18th-round pick out of nearby Duquesne University, trying him first as a starter. As a reliever, Beimel made it through Minnesota and Tampa Bay, and was about to sign with the Chicago Cubs when Dodgers general manager Ned Colletti had the idea Beimel could be a specialist for manager Grady Little to have with key lefty-on-lefty situations.

Like, with Barry Bonds. So Beimel was signed in 2006.

“That was probably my favorite team to play for, playing in L.A. in front of 40- to 50-thousand every night, just being in a city like that,” Beimel would say. “I lived my first two years in Pasadena, then moved to (Redondo Beach). When I got there it was ‘Oh my gosh, I’m never leaving here.’”

Beimel started ’06 at Triple-A Las Vegas and after a 3-0 with a 1.38 ERA in 10 games, he was called up and rarely sat. Beimel was third on the Dodgers with 62 appearances, tasked with setting things up for the later-inning heroics of Jonathan Broxton and rookie Saito. Beimel even managed to stick around for two saves in the process to post a 2-1 mark and 2.96 ERA in 70 innings.

Then, stupidly, Beimel was unavailable for the Dodgers in the 2006 NLDS against the New York Mets.

Breaking a midnight team curfew, Beimel finally admitted to slicing up his left hand on a broken beer glass while joyously patronizing a New York bar two nights before the series opener.

“We had the six hour flight and I slept the whole way there,” Beimel explained years later. “We went for dinner, had a few drinks and wound up staying out later than I should have. I took a false step onto a platform and had a beer in my hand and tripped. The beer smashed in my hand. And blood was everywhere.

“I didn’t think anything of it and wasn’t going to affect me, but I got stitches. And when I tried to throw, it was hurting and I thought they could give me something for the pain. Then I threw my slider and it ripped open and started bleeding again.

“It’s easy to go out and be over-served. You go out and pitch in front of 50,000 and have a lot of adrenaline and go out after the game, you don’t want to just go to hotel and stare at the wall so you want to go out with the guys and have a few beers and that’s fine and nothing wrong with that, but you stay out a little longer and that’s what happened in that specific instance.”

His default was to claim this all happened in his hotel room, trying to catch a glass of water in the bathroom before it hit the floor. He finally fessed up.

“I wasn’t sober by any means,” he would admit. “(And) I’m not a good liar.”

The Mets swept the Dodgers in three games, sobering enough to Beimel who, before Game 3 at Dodger Stadium, after watching the first two games in New York from his Pasadena apartment, showed up in the locker room and apologized to his teammates. None of that helped him when salary arbitration cases came up for the 2007 season. Beimel asked for a $1.25 million deal. The Dodgers countered with $912,000 and won their case.

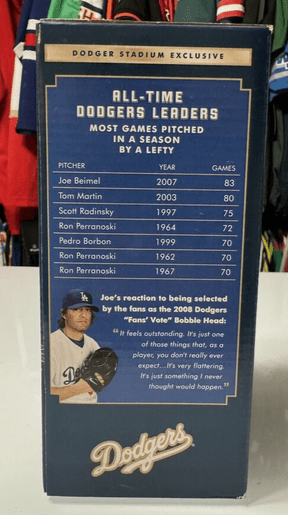

The 2007 Dodgers would miss the playoffs, bouncing around with a .500 record. Beimel made 83 appearances — setting an obscure franchise record for left-handed throwers. Broxton also came in 83 times, a total noted to be fourth-most all-time in franchise history for most appeareances by any pitcher. Beimel added one more save to go with a respectable 4-2 mark and 3.88 ERA, finishing 10 games.

That 2007 season was also Bonds’ last in the majors. He hit 28 homers to finish with an MLB-record 762 that year, but only one came against the Dodgers. As Bonds closed in on Hank Aaron’s all-time record in early August, the New York Times’ Jack Curry discovered that Beimel had been extremely effective against him.

Beimel said that to him, all it took was being aggressive rather than try to paint the corners and give Bonds what amounted to an intentional unintentional walk. “I get paid to get guys like that out,” Beimel said. “It always kind of upset me a bit when you see guys blatantly scared to throw him a strike.”

Beimel had 19 head-to-head meetings with Bonds and held him to a .063 average (1 for 16) with three walks. The one hit: A homer, of course.

When the 2008 salary arbitration case came up, Beimel and his people could lean into the fact that he was not only healthy and happy but he held left-handed hitters to a .188 average and allowed just 10 of 57 inherited runners to score in ’07.

Beimel asked for $2.15 million; the club came in at $1.7 million. They settled at $1.925 mil, still more than doubling his salary, and incentivized the deal by giving Beimel the chance to make up to $160,000 more if he was to reach 85 appearances. But that isn’t always up to a pitcher in how many times he is called in.

Meanwhile, in 2008 the Dodgers were also incentivizing fans to invest in their bobblehead bonanza giveaways. (Seriously, did fans really thing these token of appreciation were “free” if their game-seat tickets happened to go up incrementally in face-value price?)

The Dodgers weren’t just keeping pace, but setting a standard. Overseas production became more expedient. Reproduction of the player faces were better. Sponsor logos could be added to cheese them up and find a way to have the whole process underwritten.

During the month of April, the Dodgers asked fans again for suggestions. Social media wasn’t much to speak of. Companies were still trying to figure out how to harness the Internet interaction.

A good ‘ol boy named Troy from West Virginia started posting a series of basement-enhanced YouTube videos tributes, now declaring his affection for this Beimel dude. Maybe some of it was fan reaction to how new Dodgers skipper Torre invoked the Yankees custom and asked players to cut their hair. Beimel wouldn’t budge. A few Dodgers fan blogs got behind the Troy video clips. Things snowballed. Votes for Beimel started piling in — there was no limit on how many times fan could click.

Word was that Joe Beimel’s parents, Ron and Marge, were also in on this cyber push for voting him in. Why not?

By mid-April, Beimel was told that he garnished far and away the most attention for a bobblehead. It was determined he would the 25th bobblehead that the team produced since the turn of the century.

“This is a cool birthday present and a real honor,” said Beimel at the time. “I really want to thank the fans who voted for me, and I know my kids will get a kick out of this. I just hope that I get into the game that night and help the team earn a victory.”

It didn’t come out until years later, during a 2023 podcast interview, when Beimel recalled how his bobblehead almost didn’t happen.

“So this Dodgers PR guy comes up and says, ‘You’re winning the fan vote, it’s crazy, but we’re not going to give one to you — because you’re not someone who we’d make one for anyway,” said Beimel. “(The team) wanted to have one for (pitcher) Brad Penny. I was like, ‘what?’ The guys on the blogs heard about it, emailed them, ‘you better give him a bobblehead’ … so they gave me one and they gave Penny one. I never expected to ever have a bobblehead. I’m a left-handed reliever. Most people don’t even know we’re on the team. But it was an experience you’ll never forget.”

The announcement still came with some curious outcry. The then-popular and snarky website, Deadspin.com, even posted: How will Dodger fans ever live this one down? Over at LarryBrownSports.com came the anticipated response: “Have you ever heard of a situational left-hander getting his own bobblehead before? This is absurd, I tell you!”

Too late. By mid season, Beimel was even in the discussion to be added to the NL All Star team. His 3-0 mark and a team-high 38 appearances to go with a 1.08 ERA was strengthened by the fact he had not having given up a run in more than a month.

“I’m not counting on it,” he said. “If it happens, it happens.”

It didn’t happen.

But his August 12 bobblehead night did.

The first 50,000 fans were forced to take possession of the Beimel beauty upon entering the stadium — (the announced crowd was some 47,500. It was fortuitous that Beimel entered the game in the seven inning in relief of Kershaw to provide damage control. Although the Dodgers trailed Philadelphia, 3-2, at the time, they scored one in the eighth and one in the ninth on an Ethier walk-off single to pull off a 4-3 win, the victory credited to reliever Hong-Chih Kuo.

Fans felt the mojo. It was a valuable win in the pennant-race run.

Could that win have been a magical turning point in a season-long grind? It at least provided levity.

The next night, Garciaparra hit a walk-off homer to beat the Phillies, 7-6. Beimel appeared in the sixth inning of that one and gave up a walk before he was taken out.

The next night, the Dodgers capped off a four-game sweep of the NL East leaders with a 3-1 win.

When Beimel was credited for the win in a 7-5 triumph over Milwaukee — he came into the game in the top of the ninth to get the last out after the Brewers scored four runs to tie it at 5-5, and then Ethier hit a walk-off homer to win it in the bottom of the ninth — it improved Beimel’s record to 4-0 and the Dodgers were now four games over the .500 mark

The Dodgers ended up winning the NL West at 84-78, two games ahead of Arizona. Beimel would finish with a career-best 2.02 ERA in 49 innings over 72 games, not allowing a homer. The lone blemish on a 5-1 record was giving up a double to start the bottom of the 11th on a Sunday afternoon in Philadelphia and watching the next Dodgers reliever give up a game-ending homer.

After the Dodgers lost to the Phillies in the 2008 NLCS, Beimel was a free agent again.

His journey through Washington, Colorado and back to Pittsburgh looked as if he was done by age 34 after needing Tommy John surgery. But two years later, the Seattle Mariners dialed him up, and Beimel came back to gut out two more big league seasons. In 2017, at age 40, he was also pitching for the New Britain (Pennsylvania) Bees in the Atlantic League and joined the Kersey (Pennsylvania) Kings of the Federation League in time for the playoffs.

“I just wanted to hit, that was the basically the reason behind it,” Beimel said of the comeback in leagues that didn’t use the DH.

Beimel actually tried one more comeback — in 2021 at age 44, he made it to San Diego’s Triple-A El Paso.

The 4.2 WAR and 216 appearances he made in three seasons with the Dodgers was his greatest stretch in 13 MLB years. His 1.8 WAR in ’08 was statistically his most productive season.

So all by mixing a fastball with a change up, slider and sinker, Biemel lasted 19 pro seasons with 22 different teams, appearing in more than 900 games and logging nearly 1,300 innings.

“I basically played my whole career with nothing above-average as my second pitch,” he said. “I had a good sinker and could locate my fastball.”

That’s a bit of anomaly for a big-league hurler.

“I’m an anomaly for a lot of different reasons,” Beimel added.

Beimel remains the only Dodger ever to wear No. 97 and one of only two MLB players to ever wear it. He uses that as part of his social media identification — @joebeimel97 to promote his Beimel Elite Athletics training lab based in Torrance.

Included in a story in the Los Angeles Times spotlighting young pitchers who continue to undergo arm troubles, Josh Mitchell, director of player development, said Beimel will only work with youth athletes who are ready to take the next step. Beimel uses motion capture to provide pitching feedback, and uses health technology that coincides with its athletes having to self-report daily to track overexertion and determine how best to use their bodies.

When it’s all said and done, Beimel got a bobblehead to show for his big-league career. And with it came a belated spring-loaded bobblehead party thrown by Troy from West Virginia:

The legacy

Baseball fans aren’t stupid. As they learned the value of an eBay resale for bobbleheads of any shape, material or noted celebration, especially those in limited supply, someone established National Bobblehead Day in America in 2015. A year later, the National Bobblehead Hall of Fame emerged in Milwaukee.

Beimel is one of many in that collection. The Beimel bobble remains in healthy circulation, in the $20 range online, often not even taken out of the box to preserve its integrity.

The Los Angeles Angels of Anaheim also got in on the bobblehead craze in 2001. It has, aside from the abundance of Mike Trout and Shohei Ontani replicas, also found space for its Rally Monkey, Mickey Mouse and Snoopy. The Single-A Lancaster JetHawks, Rancho Cucamonga Quakes, Inland Empire 66ers, and Lake Elsnore Storm had their share of bobble giveaways as well. So did the independent league Fullerton/Orange County Flyers.

The Dodgers have not shied away from ramping up production — Beimel perhaps giving them permission to be even more creative as the competition for collectors went up exponentially.

It also became a “thing” when a player was honored with a bobblehead to do “something” to celebrate. Like in 2009, when Ramirez came off the bench to hit a grand slam in July of 2009.

The Dodgers even figured out a way to make good on a promise to do a Justin Turner bobblehead during the COVID-19 shutdown and give it to fans who missed out on attending games in 2020.

A website that keeps track of such things insists the Dodgers have far more wins than losses on bobblehead nights. It also keeps track of bobbleheads once scheduled and then trashed, like the Dodgers had ones planned for Trevor Bauer in 2021, and Julio Urias in 2023.

Beimel avoided any of that kind of messiness.

By the 2022 and 2023 seasons, the Dodgers created the demand for 21 nights of bobbleheads, ranging from one for the Lakers’ LeBron James, for USC quarterback Caleb Williams, for co-owners Magic Johnson and Billie Jean King, for singer Elton John, another for Hello Kitty, and finally, one for relief pitcher Joe Kelly in a mariachi outfit.

For 2025,the Dodgers had 21 bobblehead nights. Four of them honored Ohtani.

Sure, but did any of those players ever have a ballad written and performed about them?

Just make sure the Beimel name is spelled correctly … “e” before “i” … and, yes, there is an “e.”

Who else wore No. 97 in SoCal sports history? Make a case for:

Joey Bosa, Los Angeles Chargers defensive end/outside linebacker (2016 to 2024):

Best known: The third-overall pick by the San Diego Chargers in the 2016 NFL Draft out of Ohio State, Bosa was the AP Defensive Rookie of the Year as he sported No. 99, keeping it his first three seasons. In 2019, he took No. 97, which he wore with the Buckeyes. That was the same year his younger brother, Nick, was also drafted out of OSU, by the rival San Francisco 49ers and started to wear No. 97 himself. A five-time Pro Bowl pick, Joey Bosa signed a five-year, $135 million extension with the team in 2020, making him the highest-paid defensive player in the league. Off and on the injured reserve list, the Chargers released him after the 2024 season and he was picked up by Buffalo.

Not well remembered: Bosa is on Instagram as jbbigbear.

Jeremy Roenick, Los Angeles Kings center (2005-06):

Best known: Just one of the 20 NHL seasons Roenick logged leading to a Hockey Hall of Fame induction came in L.A. — nine goals and 13 assists in 58 games with the Kings. Roenick, who made his career in Chicago (eight seasons) and Phoenix (six seasons) before finding the West Coast via a trade with Philadelphia coming out of the 2004-05 strike-lost season, piled up 513 goals and 703 assists as one of the highest-scoring U.S.-born players. What happened in L.A.? “I struggled because I couldn’t get my skates sharpened the way I like,” Roenick once said. “I wasn’t confident in my footing. I wasn’t confident in my feet. When you feel like you’re going to fall down and you’re off balance, you’re going to struggle. Then you can’t skate the way you like, it leads to a bad back, bad groin, bad hamstrings, bad hips. It’s been a battle from the beginning. I have a different skating radius than most guys, so when I change teams, it’s tough for the trainers to find the right lie and the right cut that I need to use with my skates.”

Not well remembered: When Kings fans became vocal about Roenick’s lack of production, which didn’t help coach Andy Murray or GM Dave Taylor keep their respective jobs, Roenick famously told them all to “kiss my ass.”

Have you heard this story?

Francisco “Chico” Herrera, Los Angeles Dodgers clubhouse attendant (2008 to 2022):

In some thrift store around Los Angeles there have to be T-shirts showing up that read #DontRunOnChico and #LetChicoHit. It has nothing to do with the fictitious bail bondsman that sponsored the kids in “The Bad News Bears.”

Just check Chico Herrera’s Wikipedia page.

The Dodgers’ clubhouse kid wasn’t kidding around when the team asked if he could fill out the roster in intrasquad games during the ramp up to the COVID-pandemic delayed 2020 season. With jersey No. 97, Herrera played left field and did some pinch running. He had been with the organization as a clubbie, a ball boy and a bat boy since 2008, when he was 18 and still at Hollywood High, where he reportedly hit over .500 as a shortstop. As he went onto play at L.A. Valley College for two years, he continued working with the Dodgers — even attending a open tryout in 2012 in Arizona. As the media covered the Dodgers’ workouts, it couldn’t help but notice Herrera’s abilities. He caught a fly ball and with a strong throw kept a runner from tagging to score. He started a double play by catching a ball in deep left field and throwing Chris Taylor out at second trying to advance. In another game, he made a running over-the-shoulder catch off a Mookie Betts fly ball on the warning track, then hit the cutoff man, who threw a runner out scrambling back to first. Dodgers players like Justin Turner championed his play and called for him to get some at-bats — but it didn’t happen. The exposure he received from the local and national news all the way to MLB Network’s “Intentional Talk” unintentionally made Herrera the COVID pick-me-up story.

Anyone else worth nominating?

1 thought on “No. 97: Joe Beimel”