This is the latest post for an ongoing media project — SoCal Sports History 101: The Prime Numbers from 00 to 99 that Uniformly, Uniquely and Unapologetically Reveal The Narrative of Our Region’s Athletic Heritage. Pick a number and highlight an athlete — person, place or thing — most obviously connected to it by fame and fortune, someone who isn’t so obvious, and then take a deeper dive into the most interesting story tied to it. It’s a combination of star power, achievement, longevity, notoriety, and, above all, what makes that athlete so Southern California. Quirkiness factors in. And it should open itself to more discussion and debate — which is what sports is best at doing.

The most obvious choices for No. 80:

= Donn Moomaw, UCLA football

= Henry Ellard, Los Angeles Rams

= Johnnie Morton, USC football

The not-so obvious choices for No. 80:

= Bob Klein, USC football, Los Angeles Rams

= Duane Bickett, USC football

The most interesting story for No. 80:

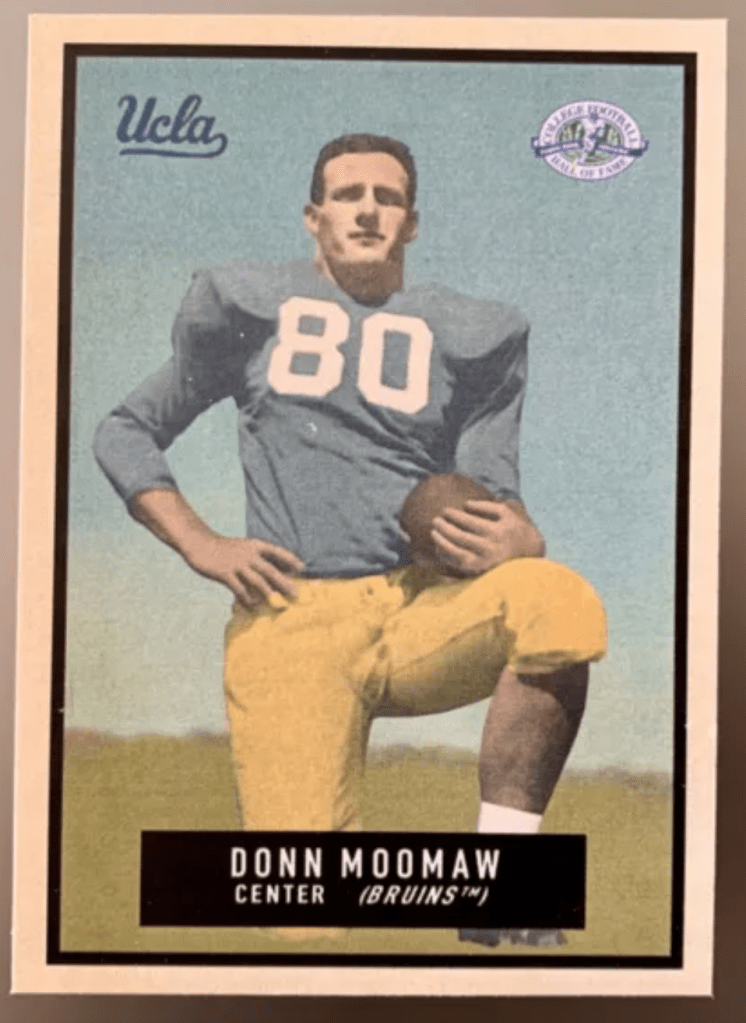

Donn Moomaw, UCLA football center and linebacker (1950 to 1952)

Southern California map pinpoints:

Santa Ana, Westwood, Los Angeles (Coliseum), Hollywood, Bel Air, Pasadena

With their first pick in the 1953 NFL Draft — the ninth-overall choice — the Los Angeles Rams selected center/linebacker Donn Moomaw, the first two-time All-American in UCLA program history and a local hero out of Santa Ana High.

Moomaw prayed on it.

Then he politely declined.

The NFL played Sunday games, which was Moomaw’s day for the Lord. It did not need any potential Hail Mary pass plays intercepting his focus.

As an end around, Moomaw could deflect to Canada, play for the Toronto Argonauts and the Ottawa Rough Riders in the CFL, and do more mid-week and Saturday engagements.

But soon enough, his rough ride of long-term pro football fame came with a change in heart. Moomaw became one of the most well-known preachers in the country. The fresh Presbyterian minister of Bel Air became a personal confidant of Ronald Reagan and his family, starting with his time as the California governor, and going all the way to the White House.

But then, the headlines that Moomaw made later in life were a cause to pause and pray some more.

The story

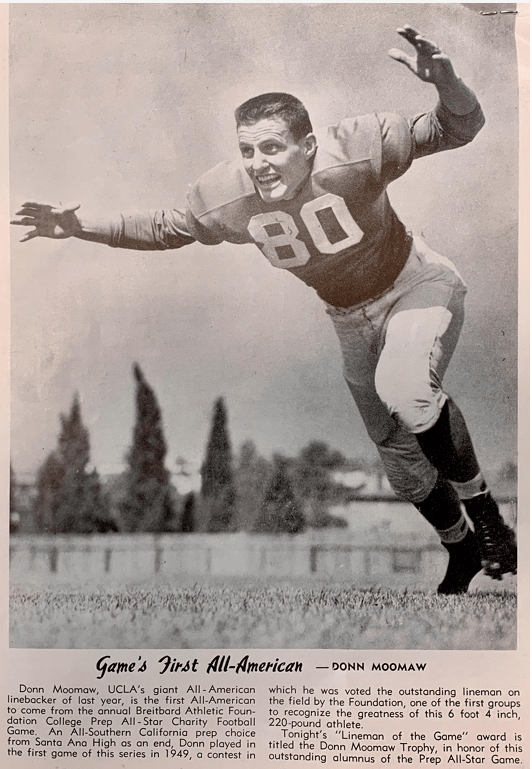

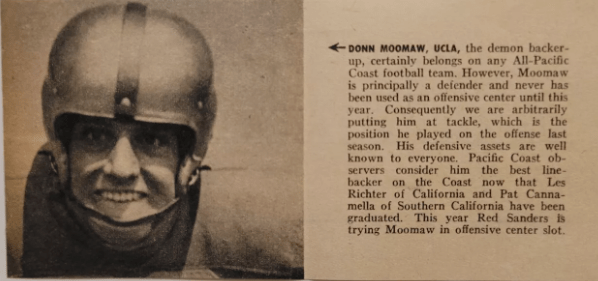

Don Moomaw’s time at UCLA was a glorious one. They weren’t booing him. When the 6-foot-4, 220-pound linebacker made a tackle, the UCLA cheerleaders would lead the crowd in “MooooooMAW!” He was known as “the Mighty Moo.”

He came just as advertised out of Santa Ana High.

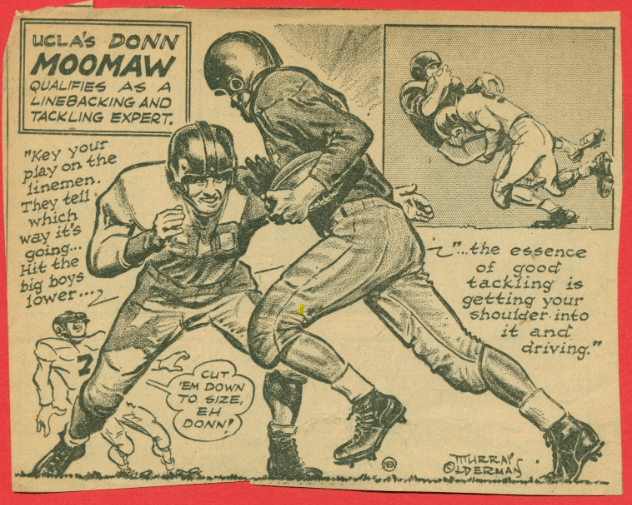

In 1949, the CIF’s Los Angeles City and Southern Section played an All-Star football game, and Moomaw was named the contest’s top lineman after a 27-7 Southern Section win before 12,000 at San Diego’s Balboa Stadium. Moowmaw, who also kicked the extra points for the Southern Section, was already partial to wearing No. 80. An award was created in his honor from that performance.

Eventually, Moomaw would become the first Bruins player in history to be twice be named an All-American — and he did it in non-consecutive seasons. First as a sophomore in 1950, and then again as a senior in 1952.

But it turned out the ’51 season would be the most impactful in his life.

Pulling double-duty as a center on head coach Red Sanders’ Single-Wing scheme, Moomaw was responsible for starting the play with a precise snapping the ball to set the offense in motion.

But then, as a linebacker, Moomaw pulled in 11 interceptions, which tied Bob Waterfield for the school’s all-time career record.

The most memorable one was in the 1951, a 21-7 win over rival USC, when Moomaw returned it for a touchdown.

And in that moment, Moomaw felt a profound change occur.

In the 2018 book “100 Things UCLA Fans Should Know Before They Die,” writer Ben Bolch dedicated a chapter to Moomaw that began with an explanation about how his girlfriend asked him to come with her to a religious rally at UCLA in September of that year. Moomaw was exposed to Bill Bright, the campus director of the Crusade for Christ movement.

That season, Moowman was in and out with injuries, trying to prove his previous season wasn’t a fluke. He questioned his purpose.

When Moomaw made that particular interception at the Coliseum, he explained later:

“I don’t know why I was over there where the ball was. I intercepted it and when I stepped into the end zone, my heart was crying … It’s strange how a simple thing like my scoring a touchdown in a game, for the first time all season, changed my life. But that’s what happened. If I’d had a good year, I might never have become interested in religion. But I had a bad one.”

The day after that interception in the ’51 USC-UCLA game, Moomaw attended Hollywood’s First Presbyterian Church. He reconnected with Bright, convinced his soul had been touched. After church, Bright talked Moomaw through a series of Bible verses about sin and salvation, and the two knelt on Bright’s living room floor.

As Moomaw became a featured speaker at Campus Crusade events at UCLA and at other California college campuses, he referred to Jesus Christ as his “new quarterback.”

In an interview 30 years later, Moomaw expanded on that season:

“I was rooming with a couple of guys, Terry Debay and Bob Heydenfeldt, who had a lot more in their lives than I had in mine and they weren’t all-Americans. They read the Bible. I came from a religious background. My father and mother were both moral, religious people, but I felt the action was not in religion but in the secular world of success.

“Maybe those injuries had something to do with it. I was very vulnerable for something more. I was exposed to a group on campus that confronted me with my accountability to God, I thought I had an accountability to myself and, perhaps, my friends, but to think I had an accountability to God was very staggering and overwhelming to me. And it was through my commitment to Jesus Christ that my life was turned around in my junior year.”

During his senior year, Moomaw’s linebacking skills helped shut down famed Wisconsin running back Alan Ameche to 31 yards on 14 carries in a 20-7 Bruins’ win at Wisconsin in Week 6 that improved UCLA’s record to 6-0 and No. 7 spot in the national rankings.

Sanders said: “That’s the greatest game I ever saw a linebacker play.”

The season’s only blemish was when No. 3 UCLA dropped a 14-12 loss to No. 4 USC in the Pacific Coast Conference title game. That also prevented the Bruins from going to the Rose Bowl.

Moomaw remarkably finished fourth in the Heisman voting, the only defensive-designated player in the top 10 of the voting.

Lineman of the Year by the Associated Press and United Press International, and the MVP of the North-South All-Star Game in Miami, Moomaw would eventually be included in the inaugural UCLA Athletics Hall of Fame class in 1984, have his No. 80 retired by the school, and the Donn D. Moomaw Outstanding Defensive Player in the USC game was established.

In 1973, Moomaw’s induction into the College Football Hall of Fame came with a biography that started: “Long after Donn Moomaw left the gridiron at the University of California-Los Angeles, the Presbyterian minister might have been heard preaching a sermon entitled ‘Whither Thou Goest I Shall Go.’ ”

A new direction

Los Angeles Rams coach Hampton Pool said a higher power told team execs that it was worth taking Moomaw in the first-round of the January 1953 NFL draft.

“We spent our first draft choice on Moomaw only after he had told us he would play this year if drafted by the Rams,” Pool insisted.

Moomaw was said to be holding out for a $10,000 salary by the team, but ultimately, things changed.

Moomaw said that “after prayerful thought,” he would pass on the NFL. He wanted to complete his studies at UCLA in the spring semester and get a degree in physical education.

Then it was reported in August of 1953 that Moomaw was all good playing in the Canadian Football League, making $700 a game in a league that never played on Sundays. A Los Angeles Times story noted that Moomaw’s focus was more on studying for the ministry.

As it turned out, Moomaw played only seven games with Toronto, skipped the ’54 season, and played just two more in Ottawa.

As one of the original Fellowship of Christian Athletes organizers who would eventually serve as president of FCA’s Board of Trustees, Moomaw received his masters of divinity degree in 1957 from Princeton Theological Seminary, followed bya doctorate at Sterling College in Kansas.

His first seven years as an ordained pastor were at First Presbyterian Church of Hollywood. Then came a three-decade term as the senior pastor of the Bel-Air Presbyterian Church on Mulholland Drive in L.A., launching in 1964.

That is where he came to know parishioners Ronald and Nancy Reagan, sharing deep discussions they had about their faith life. When Reagan was voted governor of California in 1966, he appointed Moomaw to a four-year term on the state Board of Education, starting in 1968. Reagan worked in Sacramento, but he was back home in the Pacific Palisades on weekends as a highway patrolman would drive the family in a limousine to the Bel Air Presbyterian Church to be part of Moomaw’s services.

In a 2019 piece for the Washington Post, Reagan’s daughter, Patti Davis, wrote about a time in April of 1967 when a clemency plea from a man convicted of murdering a police officer landed on her father’s desk. The previous California governor, Pat Brown, denied the request.

She said her father was “weighted down by the somber responsibility of putting a man to death … Inside the governor’s residence, my father sat quietly with the Rev. Donn Moomaw, our family’s pastor for many years. Moomaw had flown in from Los Angeles at my father’s request to pray with him. The two men talked about the Bible and about Jesus’ teachings. Then they knelt in prayer, asking for God’s guidance and help in making the decision that had haunted my father for weeks — the decision to end a man’s life. His thoughts kept veering to the officer’s family, to their grief and loss, and he was unable to justify staying the execution that was scheduled for the following morning. He said that this decision was the most painful and difficult of his eight years as governor.

“No one in the governor’s office, least of all my father, rejoiced. There would be no other executions during the eight years of the Reagan governorship.”

In a 2020 piece for the Los Angeles Times, George Skelton recalled how another Reagan offspring, son Ron Jr., came to the conclusion he was atheist after talking to Moomaw.

“I was 12 when I told my father I wasn’t going (to church) anymore,” Reagan recalled. “I said I didn’t want to be hypocritical, disrespectful and fake it. It was a waste of a perfectly good Sunday morning.

“My father was smart enough to know he couldn’t strong-arm me. And he never marshaled a compelling argument. He got Donn Moomaw to come to the house to convince me. But after 10 minutes, we were talking about UCLA football.”

Moomaw would later tell his grandson that he “didn’t think anything he ever said to Reagan ever convinced him to change his mind.”

Reagan was voted president of the United States in 1980, and Moomaw gave the official invocation at the ’81 inauguration, making mention of the hostages in Iran that had just been released after Reagan took office (video link is here):

“Gracious God our Father, we need you today maybe as never before. We have not lived up to our personal or national potential. We have seen our world from our own selfish parochial point of view. We have lived as though everything depended upon us. We confess our sin and seek your forgiveness. In this historic moment we would pray for our President-elect Ronald Reagan. We also pray for Vice President-elect George Bush, the cabinet and all others who are in positions of leadership in this new administration, may they measure well the shortness of time and the length of eternity. May they see all people and things and nations from your point of view. We thank you, o, God for the release of the hostages and for all those who have made this moment possible. And so in this moment of new beginnings our hearts beat with a cadence of pride in our country and hope in its future. Help us to stand proudly as American citizens and face every challenge with a confidence born of your spirit and humbly touched by your love and grace. So to this end we commit ourselves to this end. We pray in the name of the Lord of Lords and King of Kings, even Jesus Christ. Amen.”

In 1985, Moomaw, who officiated the 1984 wedding of Davis, was one of four clergy members to pray at Reagan’s second inauguration (done indoors at the Capital) (video link is here).

In 1991, Moomaw did the invocation at California Pete Wilson’s inauguration (video link here) and, by the end of the year, he was at the dedication of the Reagan President Library in Simi Valley (video link here).

In early February of 1993, Moomaw attended Reagan’s 82nd birthday celebration at the library. But days later, news came that Moomaw abruptly resigned from his celebrity pulpit. The 61 year old, who had a wife and five children, said in a statement released to the 2,400-member congregation:

“With my recent facing of issues dating from childhood, years of denial and faulty coping techniques, it’s become clear I have inappropriately tried in my own strength to work through my own problems. Along the way, I have stepped over the line of acceptable behavior with some members of the congregation. Now I am getting honest with myself and others maybe for the first time.

“Nothing less than full time should be given to my healing. I will begin immediately to fully evaluate my strengths and weaknesses. I will be studying and sparing no expense to honestly come to grip with issues that have inflicted pain on myself, my family and others.”

For two years, that was the only public comment about what had happened.

The confession

Don Moomaw’s two experiences in the Hollywood acting business — long before he could have used the advice of thespian Reagan — involved storylines that seemed to have already predicted his path in life.

In 1953, Moomaw played the role of a football player named “Jones” in the film “All American,” starring Tony Curtis as Nick Bonelli, a quarterback at Mid-State who eventually transfers to Sheridan University to pursue his true calling — architecture. There’s also a romantic interest with Sharon Wallace (played by Lori Nelson) also complicate matters. Moomaw’s UCLA teammate Jim Sears played the Dartmore quarterback, USC star Frank Gifford played a character named Stan Pomeroy, and Michigan star Tom Harmon was good enough to play himself.

A year later, Moomaw also played himself, but this time it was as a man of faith in “Souls in Conflict,” which starred Joan Winmill Brown playing the role of an actress, Erick Mickewood as a factory worker and Charles Leno as a jet pilot. All of them struggled to face up to their personal problems, deeply affected by attending a Billy Graham rally.

In April of 1995, reporters discovered that Moomaw had resigned as a pastor because he was accused of having “sexual contact” with five women, going back to 1989. Moomaw broke an agreement “for accountability and restoration” signed in 1990 with a group of ministers and elders, which they were to adhere to a lifestyle that “included, among other terms, a prohibition against counseling of women,” just for this possible temptation. Protestant ministers, married or not, are warned that counseling church members of the opposite sex can be emotionally perilous.

“Sexual liaisons by pastors with members of the congregation breach Christian ethical principles by using a trust relationship for personal advantage or pleasure,” said the Rev. Charles Doak, a longtime officer of the Presbytery of the Pacific.

That clerical ruling meant Moomaw could not perform his duties for two years.

“I really admire Donn’s sense of courage in facing the discipline of the church rather than take the cowardly way out,” said the Rev. Robert Henley, an associate pastor on the Bel Air staff until late 1993.

A few months after Moomaw resigned, another Presbyterian pastor down the hill in the San Fernando Valley, the Rev. Robert T. McDill, quit when he was found by the Presbytery of San Fernando to have committed the “offense of unsolicited, inappropriate touching with sexual implications.” This was part of a larger scandal happening nationwide. A piece in the Philadelphia Inquirer posted in 1995 had the headline: “In Ministry, Dealing with Temptations of the Flesh — The Concern is that Affairs Can Be Harmful.”

In early 1997, Moomaw came back, first as a guest speaker at St. Andrew’s Presbyterian Church in Newport Beach. He used a sermon based on the Gospel of Matthew about the apostle Peter’s remorse after he denied three times that he was a follower of Jesus.

“Peter fell, then he had a recall. . . . Some of the best leaders have been people who have been wounded,” Moomaw said.

A full-time return came at the 800-member Village Community Presbyterian Church in Rancho Santa Fe in July of 1997.

“I believe that some of my best work might be ahead of me,” Moomaw, 65, told the Los Angeles Times. “I’ve been in the limelight ever since junior high; in football I’d hear my name chanted over and over by a crowd. If you get your strokes and validation that way, it can become a very seductive way to live. I’m so enjoying the reentry that the past is pretty insignificant to who I am right now. …

“We have closure on all of this and don’t feel a need at this time to publicly rehearse it any further.”

In a 1981 story that Mal Florence wrote about Moomaw for the Los Angeles Times, the topic of him passing on the NFL’s Rams instead of his soul-searching “lifetime contract” he made as a servant of God came up again.

“All my life I wanted to play for the Rams,” said Moomaw, who had just been named commissioner of weight lifting for the 1984 Olympic Games in Los Angeles. “I’d like to be playing for them now. … It was beautiful to be drafted by the hometown team. But, as a young man, I had to deal with some very heavy things about my vocational life.”

Moomaw said when the Rams drafted him, he had to come to the realization that “I was raised in a home where we didn’t do anything on Sunday. I remember the first time I went to a show on Sunday. I don’t think anyone who ever committed adultery or murder felt any worse than I did.”

Moomaw agonized over the decision, and as he prepared to play in a College All-Star game in Chicago, he said he felt a need to give the Rams an answer. He even drove to the Ram’s office, got out of his car, walked into the middle of the street and then returned to his car.

“I didn’t know what I was going to tell them,” Moomaw said. “I was dealing with years of anticipating playing for the Rams and now I was being wrenched between my lifetime vocation and the pro football opportunity.”

When Moomaw was 87 in 2018, he returned to the Rose Bowl, acknowledged as an honorary captain in front of the UCLA crowd before a game against Arizona.

Ten years earlier, he wrote a post on his blog about his “contentment in retirement.” The words by Moomaw, who died on Feb. 10, 2025 at age 93, remains a rather poignant way to remember him and his message:

“The question I ask myself is: ‘Haven’t I earned the right to take time to listen to the wild animals scurrying around in the field behind our home in Bel Air, or watch the wind blow through the trees, play with my grandchildren, pause to talk to a neighbor, take lazy trips in the RV and swing a rusty golf club and not feel useless, worthless or just plain guilty.’

“All those years I preached and tried to embrace a hard hitting gospel by stressing concepts like, ‘Don’t waste, squander or fritter away time; make your life count; you are saved to serve, burn out don’t rust out, etc.’ Discipline, duty and determination are characteristics of an expendable servant of Christ (and incidentally a winner). I still hold to these and other calls to New Testament discipleship. And I believe one can be at peace and serenely happy while fully exercising their gifts and honoring their vocation.

“But, I am now in retirement and for the last few years rather than enjoying the freedom of non-responsibility or beating myself up with the shoulds, musts, and oughts, of my profession, I have found myself with less inner peace, serenity and contentment then when I was going full out in my pastoral ministry.

“Playing golf only exacerbates my feelings of uselessness. … Feelings of being needed, of accomplishment, of achievement and fulfillment, which used to define who I was, are far less apparent then they used to be and much less relied upon. … I subtly realize there will be no classes to attend, no football games to be played, no crowds chanting my name (at college football games… the elders wouldn’t permit it on Sunday mornings), no sermons to prepare and preach, no staff to work with, no tasks to accomplish and little stroking of the ego.

“So here are some final suggestions I am considering as I plow ahead toward experiencing the full council of God.

= Love others and let others love you. (“Be cheerful. Keep things in good repair. Keep your spirits up. Think in harmony. Be agreeable. Do all that, and the God of love and peace will be with you for sure.” II Cor. 13:11.)

= Accept your present identity, independent of your vocation, public recognition or verifiable

success.

= Laughing is healthy, but don’t denigrate tears. (“There is a time to weep and a time to laugh: a time to mourn, and a time to dance.” Ecc. 3:4.)

= Continue to nurture your intellectual curiosity. (My wife, Carol, and I yearn “to know.” We are fascinated by each others new insights, reflections on current events and stretching to see what is around the next corner.)

= Work to correct issues contributing to discontent, and commit to God in believing prayer all things beyond your control. (I once heard a professor of Psychiatry at Harvard University say, “a major characteristic of a whole person is to be able to live in a world of ambiguity with peace.”)

= Take care of responsibilities when they come to mind. (To procrastinate is a set-up for worry and fear.)

= Bring all worries, cares, problems, emptiness and fears to God.

Who else wore No. 80 in SoCal sports history? Make a case for:

Henry Ellard, Los Angeles Rams receiver (1983 to 1993):

A three-time Pro Bowl pick from the Rams, Ellard led the NFL with 1,414 yards receiving to go with 10 touchdowns in 1988, and he led the NFL with yards receiving per game with 88.4 and 98.7 in consecutive years. As a rookie out of Fresno State, Ellard returned a punt 72 yards for a touchdown in a critical win over New Orleans to clinch a wild-card berth with a 26-24 win. Before moving on to Washington, Ellard held the Rams’ team records for career receptions (593), receiving yards (9,761), 100-yard receiving games (26), punt return average (11.3) and total offense (11,663 yards). While with the Rams, Ellard qualified for the 1992 U.S. Olympic trials in the triple jump but injured his hamstring and did not make the team. He was six all time in the NFL with receptions when he retired (814) in 1998.

Johnnie Morton, USC football receiver (1990 to 1993):

The All-American out of South Torrance High led the nation with 78 receptions for 1,373 yards to go with 12 touchdowns as a senior in 1993. As a freshman, he caught a 23-yard touchdown pass from Todd Marinovich that sealed a 45-42 win over UCLA with 16 seconds to play. Morton became the 21st overall pick in the 1994 draft by Detroit and put in 12 seasons in the NFL.

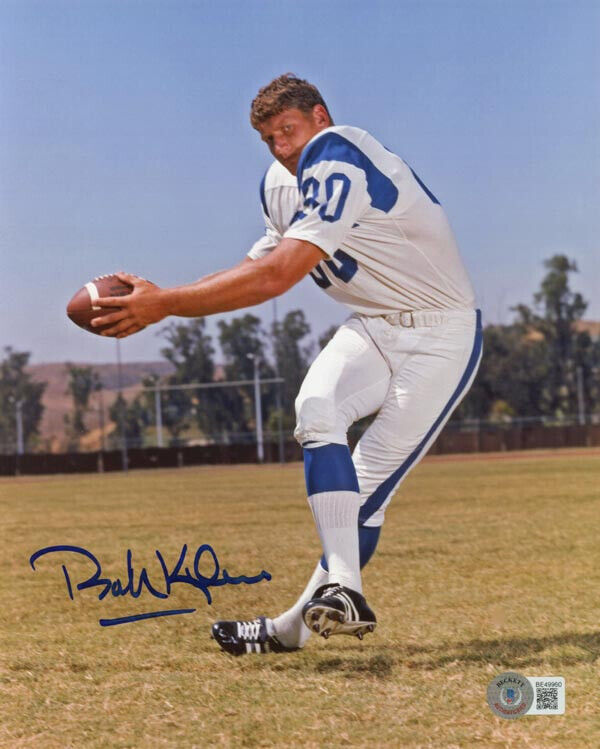

Bob Klein, USC football tight end (1966 to 1968); Los Angeles Rams tight end (1969 to 1976):

Out of St. Monica High in Santa Monica, Klein was part of the USC 1967 national title team and after his senior season in 1968, was the 21st overall pick by the Los Angeles Rams. In two seasons as a backup to Billy Truax, Klein did most of the blocking from the tight end spot. He did catch a touchdown pass in a 23-20 playoff loss to Minnesota. After Truax was traded, Klein would average 21 catches a year from ’71 to ’76. In a 1985 vote of the fans, Klein was named the tight end on the Rams’ 40th anniversary team. His pass-catching flourished when he was traded to San Diego and caught 91 passes for eight touchdowns from 1977 to ’79 before he was replaced with Kellen Winslow.

Duane Bickett, USC football linebacker (1982 to 1984):

The 6-foot-5, 250-pounder played tight end and defensive end at Glendale High, catching 47 passes for 581 yards and seven touchdowns as his team won the Foothill League. Also a standout in basketball, Bickett emerged as the CIF-SS 2A Co-Player of the Year, averaging 18 points a game his senior season for a team that won a state title. Recruited as a tight end by the Trojans, Bickett was converted to linebacker as a sophomore and posted 31 tackles and three interceptions. As a junior, he led the Trojans with 105 tackles and two interceptions and was named to the conference’s All-Academic team. As a senior, he recorded 151 tackles (16 for loses), 13 pass deflections and an interception for a Trojans team that upset Ohio State in the Rose Bowl. He was Pac-10 Defensive Player of the Year and first-team All American. He became the fifth overall pick by Indianapolis in the NFL draft ad had a 12-year career.

Have you heard this story?

Sam Huard, USC football quarterback (2025):

The method by which Sam Huard landed on the Trojans’ roster and was listed third on the QB depth cart when the 2025 season is a feat unto itself. He spent his first two seasons at the University of Washington (’21 and ’22), a year at Cal Poly San Luis Obispo (’23) and a year at Utah (’24) before the Trojans’ red-shirt senior was assigned No. 7, the same number he had back at Washington as well as the number that his father, Damon Huard, wore when he was a star QB for the same program in the 1990s. It was also convenient that Sam Huard came to USC to play for his uncle, Luke Huard, the Trojans’ offensive coordinator and quarterbacks coach.

Prior to USC’s Week 10 game at the Coliseum on a Friday night against Northwestern, nationally televised on Fox, Huard was listed as No. 7 in the Trojans’ official game notes. Just as he had been all season long.

Early in the second quarter, USC faced fourth-and-6 and lined up in punt formation. It was assumed that the No. 80 who ran out onto the field as the kicker was Sam Johnson, the Trojans’ redshirt senior punter all season who had been wearing that jersey number. Instead, it was Huard.

He took the long snap, angled himself to the Northwestern sideline and made a sharp left-handed 10-yard completion to freshman receiver Tanook Hines. USC kept the drive alive, went on to score a touchdown for a 14-7 lead, and eventually won 38-17, upping its record to 7-2 and boosting its national ranking from No. 20 to No. 17.

Was that legal? Well, technically, yes. At that particular moment.

Was it poor sportsmanship? Slimy? Unnecessary? To be debated.

College football teams, sometimes with rosters that exceed 100 players, are allowed to have multiple athletes with the same jersey number. It usually involves players who play on opposite sides of the ball — offense, defense or special teams — to avoid confusion. USC’s 2025 roster lists more than 30 numbers shared by two players.

On top of it all, USC is one of six schools (with Notre Dame, Penn State and the three military academies) that does not have players’ last names on the backs of its jersey, giving them something of an advantage when players use multiple numbers.

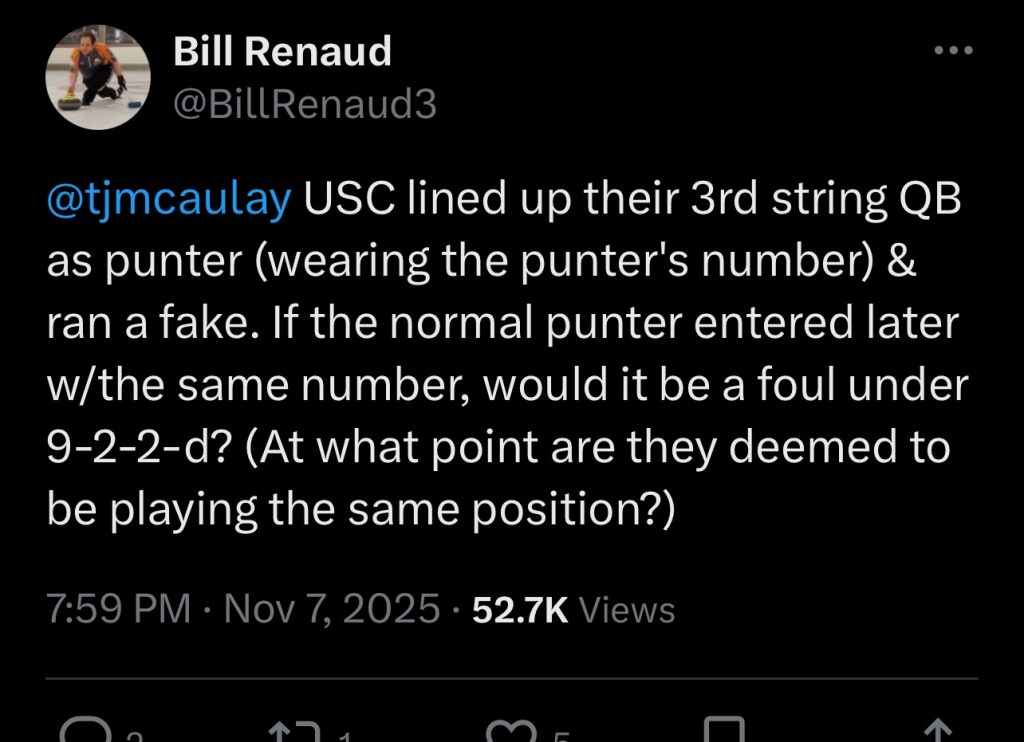

During the game, a social media post questioned the legality of Huard’s appearance in the punt formation wearing No. 80:

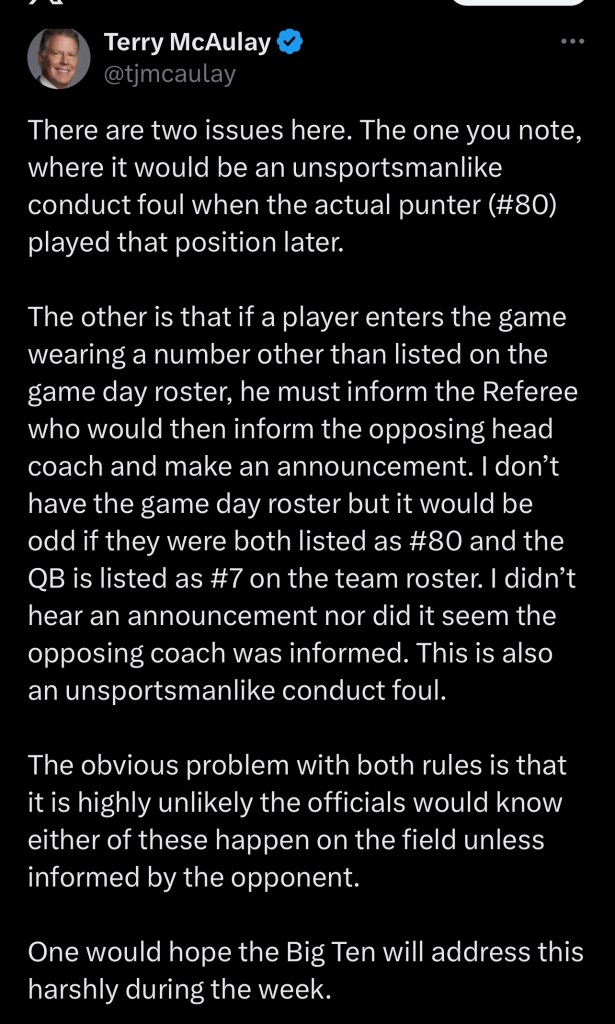

NBC’s NFL and Notre Dame football in-house rules analyst Terry McAulay responded:

Huard wearing No. 80 in and of itself wasn’t cause for a penalty, just a deceptive measure by USC. The infraction should have come when Johnson entered the game with 57 seconds remaining in the first half to actually punt, also wearing his usual No. 80.

On Sunday, McAulay continued answering questions for those who offered alternative interpretations:

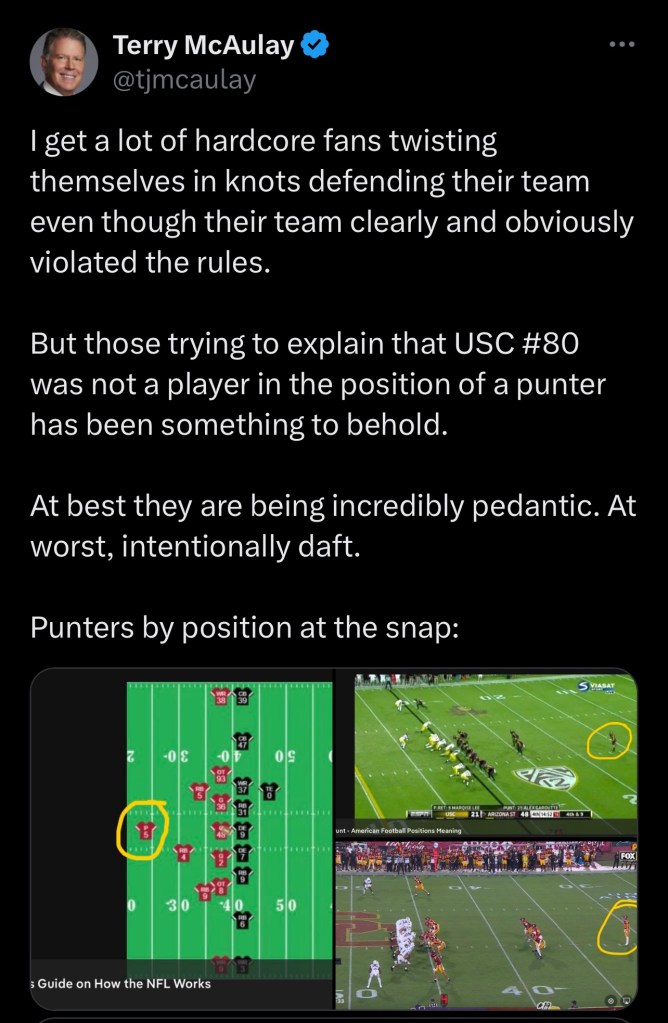

On Monday, McAulay realized he couldn’t dumb it down for those who still challenged him:

The ethical implications of the fake punt continued to be hashed out in the media all weekend. Bottom line: Was it just not a cool thing to do, legal or not? And why in that game instead of waiting to use it against a stronger opponent?

Dave Portnoy, the Barstool Sports creator and least likely person to turn to when trying to delineate an ethical dilemma, jumped on it the next day during his appearance on the Fox college football pregame show: “A fake punt that shouldn’t be a fake punt because you have a quarterback pretending to be a punter. What happened? When did this go on? Get rid of the double numbers. It’s got to go.”

And this:

USC coach Lincoln Riley said after the Northwestern win late Friday night that they they made Huard’s number change several weeks ago and joked with reporters: “It was just a well thought out thing by several of our staff members who were involved in it … You guys [have] got to pay attention. … I’m glad none of you all put it on Twitter.”

The change of Huard’s number was not noted in any USC sports information press releases all season long, even though Riley implied Huard had been wearing No. 80 since its Week 7 loss at Notre Dame.

Riley, asked about it again on the Tuesday after the game and with prep work going into the Iowa contest — where again Huard was listed as No. 7 in the USC notes and online (along with safety Kamari Ramsey) — insisted the play was “entirely legal. … We’re very aware of the rules … Our guys did a fantastic job executing it. And there’s not really a whole lot else to say.”

Had this been done before? Kind of. Some point out that Bowling Green did the same trickery in a meaningless December ’24 bowl game against Arkansas State, except the team’s punter and backup QB wore different numbers that just looked similar. When Cal played host to Ohio State in 2013, both Bears freshman quarterback Jared Goff and punter Cole Leningerwore No. 16. Goff was able to sneak in and convert a fake punt pass to get a first down at one point of his team’s desperation to stay close. Yet, No. 4 Ohio State still won its 15th in a row, 52-34.

Some USC supporters latched onto how Huard’s nomadic career as a player finally resulted in something to celebrate instead of debate:

Fox’s broadcasting team, which was not told of the number manipulation, seemed to be baffled by the trick play and tried to laugh it off. Play-by-play man Jason Benetti called the play as if Johnson threw the first-down pass, and analyst Robert Griffin III was duly impressed. They had to clarify five minutes later what really happened.

Eventually, the Big Ten officials cited an NCAA rule under “Unfair Tactics” under Rule 9, Section 2, Article 2 that read: “Two players playing the same position may not wear the same number during the game.” The conference said that “if a foul was identified when #80 (Johnson) entered the game as a punter, a Team Unsportsmanlike Conduct penalty would have been assessed resulting in a 15-yard penalty from the previous spot.” It wasn’t.

USC’s thought process would have been: If the penalty was called at that point, would it really matter? The trick kept the previous drive alive. It would have been a delayed response as USC would accept as its penance.

Some may call it “cheeky,” messing with the spirit of a policy meant to accommodate players’ number wishes instead of a coach able to manipulate a situation on the field that contributes to a win or loss.

Los Angeles Times USC beat writer Ryan Kartje agreed the play was “diabolical,” and the fallout from it equally fascinating as it was “transforming a random trick play into a sort of college football Rorscharch test.” Kartje admitted the official small-print game-day depth chart/roster had Huard and Johnson both as No. 80, even if Huard was listed as No. 7 with the online roster as well as the USC sports information department game notes.

“You can feel how badly the Big Ten wants to chastise USC for what it probably feels is a play unbecoming of the conference,” Kartje wrote. “Riley could argue about semantics until he turns blue in the face. The number change was technically within the rules. And technically, there’s no rule that a quarterback can’t line up 13 yards behind the center. We’re only assuming, in this case, that the player is a punter. … And really, if you think about it, that kind of captures Riley in a nutshell. Intermittently brilliant. Consistently brash. And definitely not here to make friends.”

It’s hardly a teachable moment for kids in a college curriculum setting. If anything, it shows that bending the spirit of a rule is fine — until someone realizes your loophole discovery and closes it.

Two letters to the Los Angeles Times editors after Kartje’s story:

So someone had an idea to change a number on a submitted roster each week. Instead of, “No, that’s not how we compete, we’re better than that,” the reaction was, “Cool, look how smart we are.” Great. Now opposing coaches need to compare submitted rosters to real rosters whenever they play the University of Shady Coaches. = Richard Brisacher, Mar Vista

USC football has a long and well documented history of scandal. But they may have hit a low by sending in a backup quarterback to punt using the same jersey number as their actual punter to pull off a trick fake punt against Northwestern. While technically not illegal, it’s just Bush league (pun intended). Then after the game, Coach Riley joked about saying “we’ve got some creative guys on our staff.” Two things: great example Riley sets for his players about playing the game with integrity and fairness. Also, it’s no wonder Riley does not have many admirers among college football coaching community. = Jack Nelson, Los Angeles

Huard is left as the one who has to wear it.

He did so, apparently with some glee, as he was sent into the game in the fourth quarter to relieve starter Jayden Maiava and run off the clock as the quarterback taking snaps and handing off the ball. Huard then was summonsed to lead the USC Marching Band in a ceremonial baton wave, a tradition granted to those who might deserve post-game attention. It seemed as if both appearances later in the game and with the band were rubbing it into the Northwestern faces rather than celebrating something achieved.

(Double-dog dare anyone else on the Trojans’ team to pull on No. 80 — especially as it officially offered to dogs whose owners want to dress them up for a game-day tailgate, as found at the local PetSmart):

Emmet Sheehan, Los Angeles Dodgers pitcher (2023 to present):

Sheehan was the first Dodger to ever wear No. 80 when he made his MLB debut as a 25-year-old in June of 2023, throwing six no-hit innings against San Francisco. He would post a 4-1 record and 4.92 ERA in 60 innings over 11 starts before succumbing to Tommy John Surgery in the spring of 2024. He returned as a starter in the team’s rotation during its 2025 World Series run, pitching key innings in relief during the playoffs.

Isaac Bruce, Los Angeles Rams receiver (1994):

Bruce would become a Pro Football Hall of Famer (Class of 2020, inducted officially in 2021) based on 14 years with the Rams’ franchise (and two more in San Francisco). But he only played one of his pro seasons in Southern California. However, Bruce left his hometown of Ft. Lauderdale, Fla., and spent two seasons split between West L.A. College and Santa Monica College, all to get his grades up before transferring to Memphis State for his last two years of college eligibity. “I left South Florida as a 17-year-old with two bags, and I landed right in Inglewood,” he said. “L.A. was very similar to what I was used to — a melting pot. It didn’t disappoint me at all. … One of the best moves I felt like I ever made in my life.” The Los Angeles Rams of Anaheim took him in the second round. ““So now I’m not a broke college student in Los Angeles. I’m back with a contract and an opportunity to pursue my dream.” He was the Rams’ Rookie of the Year, making a 34-yard touchdown catch for his first NFL reception among just the 21 he had all season. His 14 years with the Rams as part of “The Greatest Show on Turf,” allotted him more than 1,000 receptions and excess of 15,000 yards receiving and 91 touchdowns in 223 games.

Bucky Pope, Los Angeles Rams receiver (1964 to 1967):

Only two players listed in the NFL Record & Fact Book have managed to have a season with at least 24 catches and average 30 or more yards per reception in that year. One of them was Frank Buckley Pope III, a 6-foot-5, 195-pound former basketball star player who started at Duke and finished at small North Carolina college called Catawba to graduate. He caught the end of Rams general manager Elroy “Crazy Legs” Hirsch, who picked him in the eighth round of the 1964 NFL Draft and nicknamed him “Catawba Claw.” In his rookie season, Pope tied for the league lead with 10 touchdown catches, including a league-high of 95 yards (on a toss from Bill Munson) and, for the season, made 25 catches overall for 786 yards, or an average of 31.44. That was just a shade below the mark of 32.58 yards per catch with 24 catches by the Boston Yanks’ Don Currivan in 1947. Currivan, as it turns out, finished his career primarily as a defensive back with the Rams wearing Nos. 40 and 34. Pope, who started 11 games as a rookie, never started a game again — he injured his knee in the preseason of ’65 and sat out all year. That balky knee got into just 19 games over three more seasons before he was finished in Green Bay in 1968 at age 27 after trying to make the Packers in ’69 but was cut.

Anyone else worth nominating?

1 thought on “No. 80: Donn Moomaw”