“3,000: Baseballs Elite Clubs

for Hits and Strikeouts”

The author: Douglas J. Jordan

The details: McFarland, $35, 232 pages, released Nov. 20, 2024; best available at the publishers website and Bookshop.org.

A review in 90 feet or less

The latest Clayton Kershaw Challenge is upon us.

It compares far less to the Hollywood portrait of Stan Ross. It’s much more up on easel with Bob Ross. If you think about thing that way.

But, why would you?

In the Bernie Mac movie from some 20 years ago, “Mr. 3,000,” Stan Ross is the prima donna designated hitter for the Milwaukee Brewers who retired in 1995 just as his team was amidst the playoff race because he reached the fabled career hit milestone, which he assumed would guarantee him Baseball Hall of Fame immortality, and that was all it seemed he was playing for.

Then came the nasty “clerical error” — three hits were taken away from him because of a rain-canceled game where the stats didn’t count. All his post-retirement “Mr. 3,000” branded endorsement deals backed out, and he couldn’t get voters to get him into Cooperstown. So at age 46, he makes a comeback. He goes hitless in his first 27 at-bats. Then, in the last at-bat of the last game of the season, he’s one hit short, but the team needs him to lay down a sacrifice bunt that could help them clinch a win that would get them a surprise third-place spot in their division.

Sacrifice himself for the good of the team? You can’t make up these scripts. Except, here, they did.

And then, some baseball scholars tried to see how he really measured up — why would he not make it in with “merely” 2,999 hits? Steroids?

(See a Harvard sports analysis on this that may make you think twice about its entitlement to public funding).

When Kershaw’s 2024 season started late and ended early — it was a -0.3 WAR performance of seven starts while the team was fully geared up for their World Series run — he found himself 32 strikeouts short of 3,000 for his career, having racked up just 24 in 30 innings over seven starts.

He was 36 years old, held out on the 60-day IL at the beginning as he recovered from a surgically repaired left shoulder, started with a four-inning game on July 25, and ended it after the first inning of a game on August 30 in Arizona because the big toe on his left foot was acting up.

The offseason seemed 50/50 on whether he’d just retire. His Hall of Fame status was already pretty well locked in. On Baseball-Reference.com, the average Hall of Famer’s “black ink” is 40 (Kershaw has 65), the “gray ink” is 185 (he has 188) and the Bill James’ Hall of Fame monitor of 100 shows Kershaw blown past that at 211. By “Hall of Fame Standards,” the average is 50, and he had 62, with a 79.2 career war, 21st all time by a starting pitcher. His season-by-season stats compared, from age 26 to 36, to either Tom Seaver or Pedro Martinez, as well as Roy Halladay, Chief Bender, Whitey Ford and Randy Johnson. All HOFs.

(Also, we didn’t realize that on that website, it notes Kershaw’s nicknames have been “The Claw, “Kid K,” “The Minotaur,” and, of course, “Kersh.”)

Three times he led the NL in strikeouts — 248 in 2011, 232 in 2013 and a career-best 301 in 2015. Yet the last time he had a season of 200 or more Ks was 2017. A resume with three NL Cy Youngs, 10 All Star appearances and an NL MVP, already the Dodgers’ franchise leader in strikeouts …

Why bother coming back? What’s left to gain through more pain?

A one-year, $7.5 million incentive-hefty contract signed during the Dodgers’ ’25 spring training allowed him to come back with his pals, show off scars from both his toe and a knee surgery, and then take a seat on another 60-day injury list.

He’s not eligible to come back until May 17, unless the Dodgers make some clerical error and delay his return even longer. After setting a franchise record by using 40 pitchers in 2024, as well as 39 in ’23 and ’21, they’ve already burned through 20 in their first 24 games of the ’25 season. Once upon a time, an MLB wouldn’t even need 20 pitchers in an entire season.

So there you have Clayton Kershaw. His commonality with the late Bob Ross — he’s an artist known these days for painting the corners rather than his primary color pallet bursts, his image alive on T-shirts, and he’s likely to be the one the Dodgers go to if they ever decide to do a Chia Pet giveaway with the organic representation of his beard and hair.

What we’re about to witness with Kershaw isn’t so much a Hollywood sequel to “Mr. 3,000,” but it could be called “Desperately Seeking Strikeouts.”

In Andy McCullough’s 2024 book, “The Last of His Kind: Clayton Kershaw And the Burden of Greatness,” the reader gets a far deeper understanding about Kershaw’s competitive spirit and love of his teammates — especially getting to be a career bridge in the story of Shohei Ohtani — was worth whatever rehab time needed to work his way into shape.

His 18th — and final? — season, in a career where no one else in franchise history pitched in more than 16 seasons (Don Sutton, while Don Drysdale did 14), Kershaw seems so much distant from the 20-year-old who came up in 2008 and figured it all out. He didn’t have to strike everyone out, even though he almost did. His career-high was 15 in a game, which came in the 2014 no-hitter against Colorado (and included no walks) in an 8-0 win.

So, of all those pitchers who have reached 3,000 career Ks — and without taking much account into any other category or achievement — who might be the one Kershaw is most comparable?

Start right away by noting Cy Young is 25th on the all-time list with 2,803. Even Mike Mussina has 10 more, and he wasn’t even trying.

After sifting through the biographical data that Doug Jordan details in his new-ish book, we’ve kind of think Kershaw has set himself apart from the 19 current members of the 3,000 K club.

There are two active pitchers on the list: Justin Verlander (No. 10 at 3,439, at age 42) and Max Scherzer (No. 11 at 3,439 at age 40). Only two have done it with one franchise: Walter Johnson (3,509 with the Washington Senators from 1907 to 1927) and Bob Gibson (3,117 with the St. Louis Cardinals from 1959 to 1975).

The top left-handed hurlers are Randy Johnson (No. 2 at 4,875) and Steve Carlton (No. 4 at 4,136).

Maybe he’s most comparable to Carsten Charles (C.C.) Sabathia, who went 19 seasons to get 3,093, is a lefty, and just got Hall of Fame approved. Sabathia is No. 18 on the list, and the only left-hander ahead of Kershaw.

Disappointed by that comparison? A Dodger to a longtime Yankee (11 of his 19 seasons)?

Jordan writes that the path to his book takes research laid down by Fred McMane and Stuart Shea in their 2012 book, “The 3,000 Hit Club: Stories of Baseball’s Greatest Hitters.”

Jordan then doubles down.

He wants to find out more not just on the hitters, but also those pitchers who match that total and if it is similiar or really different pursuits.

That leads to all sorts of statistical tables, bar charts, maps, chairs, napkins and water glasses. (Point of fact: Anaheim Stadium has seen two people reach their 3,00th hit — George Brett and Rod Carew. Dodger Stadium fans have never witnessed it).

From his list by dates of when all 19 achievements were accomplished — Cap Anson was the first (date unknown); Hank Aaron, Willie Mays and Roberto Clemente all did it in 1972; Miguel Cabera was the last in April of ’22 — notes how many won MVP Awards, how many All-Star appearances were achieve, and, maybe not surprising, how many never won a Gold Glove. His research also implies we may not see another 3,000th hit until …

Freddie Freeman in 2028 when he’s 38 and playing in Anaheim? Mike Trout in 2032 when he’s 40 and playing in Philadelphia? Gives us something to think about.

Jordan then ventured out to study the pitcher’s achievement of 3,000 Ks, and if there are any more comparisons. That, and what’s the real value of 3,000 for each category.

Kershaw’s pursuit of 3,000 could have run simultaneously to that of former teammate Zack Greinke, who, through 2023, had 2,979, didn’t pitch for anyone in 2024 and has not officially retired although he’ll turn 42 this October.

Don Sutton, who had 2,696 of his 3,574 career strikeouts over 16 seasons with the Dodgers, was the eighth in MLB history to reach No. 3,000 when he did it with Milwaukee in 1983. Quite a feat for a Hall of Famer who never won a Cy Young Award and made only four All Star games. It’s the result of having 100 or more Ks in 21 seasons.

The last to get to 3,000 was Max Scherzer as he was posting a 7-0 in 11 regular season starts as a Dodgers’ teammate of Kershaw in 2021. On Sept. 12 of that season, Scherzer struck out the Padres’ Eric Hosmer to hit the mark at Dodger Stadium.

Jordan notes that it took Dodger Stadium almost 60 years to see either a 3,000th hit or a 3,000th strikeout. Two years earlier, Detroit’s Justin Verlander reached 3,000 at Angels Stadium when he whiffed the Angels’ Kole Calhoun (who reached first base on a passed ball because it was a wild itch in the dirt).

More Jordanesque research: If/when Kershaw reaches 3,000 Ks, he will be the third born in the state of Texas (after Nolan Ryan and Greg Maddox), which will tie California (Randy Johnson, Sabathia and Tom Seaver).

Jordan finds a more fitting comparison between Kershaw and one-time Dodgers budding star Pedro Martinez, who recorded the first 127 of his 3,154 career Ks in L.A. (and his brother, Ramon Martinez, is No. 9 all-time on the Dodgers strikeout list with 1,315)

Jordan writes: “It’s likely most fans don’t realize how great (Kershaw) truly is. The man has a career ERA of 2.48 … There are interesting parallels between the careers of Kershaw and Pedro Martinez (pitchers with an ERA+ above 150) and both won three Cy Young Awards in four years. Martinez finished 219-100, while Kershaw, to date, is 210-92. They both deserve to be in the conversation of greatest pitchers ever.”

And, should Kershaw never come back? He’d might be just another Jim Bunning (who came up 145 short). Another one-time Dodger. Who is in the Hall of Fame.

Or Frank Tanana, who was just 227 short, most of them with the Angels.

Or, like Cy Young.

As a textbook case, those comparisons wouldn’t be the worst thing.

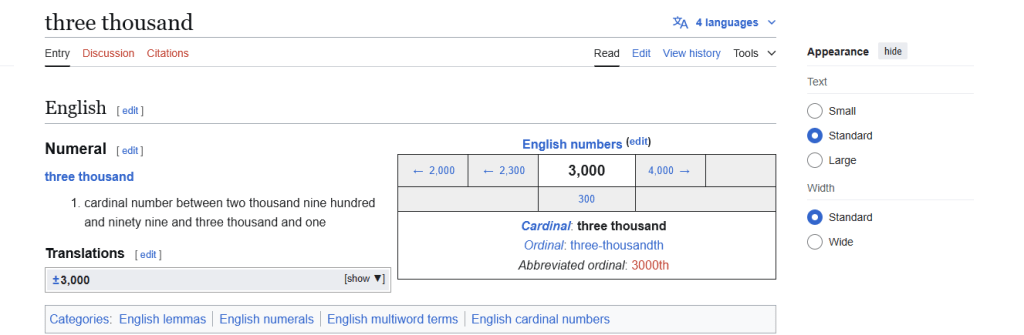

It’s just a cardinal number. Divisible by some rather common denominators.

How it goes in the scorebook

If anyone still has a functional Lenovo 3000 C laptop from the turn of the century, see if it can compute why Sir Minotaur would care at this point about a 3,000 chaser. He didn’t seem to be too bothered when Dave Roberts removed him from a seven-inning perfect game he was throwing in Minnesota one cold day — and then later was miffed.

He does it, and there’ll be a fresh bobblehead night and all the to-do that makes even the most head-in-the-ground Hall of Fame voter feel guilty if it’s not on 100 percent of the ballots. Hand out a copy of this book to everyone and learn them something.

There’s no mystery or science or theater left to factor into this 3000 equation.

It’s just another thing to put on a T-shirt in the end.

You can look it up: More to ponder

== Here are all 33 members of the 3,000th hit club and all 19 members of the 3,000 strike outs club.

== Indulge us more as we were trying to figure out:

Which pitcher has accounted for the most strikeouts in baseball history — creating them on the mound, and combined with what they contributed at the plate?

Based on all his National League non-DH plate appearances, we would have banked on Randy Johnson as the most likely. The USC grad had 17 seasons when he was required to hit (14 of them between the less-agile ages of 34 and 45), and whiffed 296 times. Added to the 4,875 he mowed down on the mound, that makes: 5,171.

Babe Ruth only struck out 488 batters during his 10-year pitching career. Even though he made 17 or more starts between 1915 and 1919 (and, on a whim, threw a complete-game victory with the Yankees at age 38 in 1933, allowing five runs and 12 hits with three walks and no Ks). Consider that even as a big-time home run hitter, he only struck out 1,330 times (exactly No. 150 all time at the moment, between Dean Palmer and Asdurbal Cabera, with Manny Machado likely to pass him up soon and drop Ruth into the next tier of 50 players-per-chart). Even so, Ruth led the league in striking out at the plate five times, but never had more than 100 — he had a career average of .342 for crying out loud. Combining his Ks at the plate and on the mound: 1,818.

Fullerton’s finest, Walter Johnson, was maybe the best-hitting pitcher of all time. A .235 career mark saw him reach .433 in 1925 at age 37 (42 for 97 with two homers) and .348 in his final season of 1927 at age 39 (16 for 46). He struck out 419 times in his 21 seasons, at times playing in more than 60 games a year as a pitcher. His 3,509 strike outs on the mound are No. 9 all time. Added up: 3,928.

Cy Young: The 2,803 he had on the mound, along with 381 at the plate (he was a .210 hitter) are hardly worth adding together in this exercise, but he would be a 3,000-number guy of both could be combined. So there’s that. Kershaw as well is already a 3,000 guy based on his current K total on the mound and the 211 he had at the plate and will never have to bat again.

So does the Big Unit size up as the largest in this category? Hardly.

Johnson’s combined total is still more than 500 short of what Nolan Ryan did only on the mound.

The MLB all-time strikeout record of 5,714 piled up 2,416 with the Angels over 291 games covering eight seasons, the franchise leader. That goes with 156 complete games, 40 shutouts and four no-hitters. In his days with the Mets and Astros, Ryan managed to whiff at the plate even more than Johnson — 371 times — during the 15 seasons he appeared as a hitter (two if two of those seasons were a combined three at bats). Add it up and that makes: 6,085.

Or, more than 3,000 doubled. Ryan is Mr. 6,000.

1 thought on “Day 15 of 2025 baseball book reviews: The mystery, the science and the theater of reaching 3,000”