“Big Loosh: The Unruly Life

of Umpire Ron Luciano”

The author: Jim Leeke

The details: University of Nebraska Publishing, $32.95, 216 pages, to be released in July 1, 2025; best available at the publishers website and bookshop.org.

A review in 90 feet or less

In the 1980s, the baseball media world could count on three things:

= A movie that directors insisted “was not a baseball film at all but really one about (fill in the blank)” made it as a big box-office draw. The lineup included “The Natural” (1984), “Bull Durham” (1988), “Eight Men Out” (1988), “Field of Dreams” (1988) and “Major League (1989);

= Hearing John Fogerty’s song, “Centerfield,” meant whatever you were watching needed a sound track, over track or background score to clue you in that it had something to do with the game;

= Ron Luciano, retired umpire, wrote another self-deprecating book. While pitching Miller Lite beer. After trying to become a national baseball TV analyst. He needed to be heard, seen and, if possible, felt, and hope you were entertained.

If Fernando Valenzuela and Pete Rose generated the most baseball relatable headlines in the ‘80s, Luciano created the most commentary about it and much more.

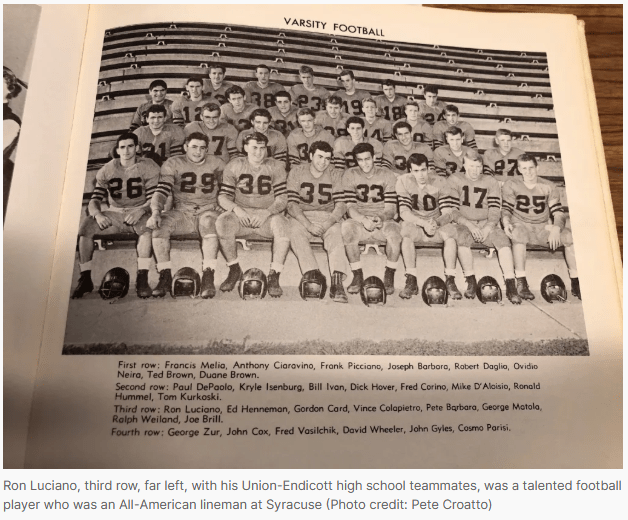

The 6-foot-4, 240-pound former All-American Syracuse offensive/defensive lineman who bridged the Orangemen teams in the late ‘50s of Jim Brown and Ernie Davis was drafted in 1959 as the last pick in the third round, No. 36 overall, by the NFL’s Detroit Lions. He wasn’t healthy enough to pursue that, or to teaching, so he turned to umpiring school in Florida, thought he was decent at it, and that’s where his path took him.

He would emphatically call someone out on strikes, point a pretend pistol to shoot down a runner at first base trying to leg out a hit, or kick some dirt back on a manager he just ejected, especially one who overstepped his way into onto his performance art stage.

If you pronounced Luciano as he preferred — Luk-CI-an-o — that was great. If it was Loo-SEE-ano, that’s where the nickname “Loosh” of “Loochie” comes up.

His life as a big-league umpire lasted only 11 seasons, starting in 1969 and going through the end of ’79. Highly regarded on the grade scale. Highly volatile as far as Earl Weaver, Billy Martin, Dick Williams or any other AL manager was concerned — as well as very conversational as far as Tommy Lasorda, the Dodgers’ third-base coach in the 1974 World Series, was concerned and has been kept in the MLB video library for frequent re-runs.

There was a time when the loneliness of umpiring led him to quit and sign on with NBC’s Game of the Week team, two seasons as a partner with Merle Harmon as the backup team. Joe Garagiola, who helped Luciano develop a media-friendly persona, must have made it look pretty easy. The Ernest Borgnine look-alike made Harmon at least look good. Luciano also worked with Dick Enberg in ’81, but the MLB strike interrupted all that.

By then, Luciano already pivoted to first of what would be a succession of hardcover-turned-mass-market paperbacks, usually involving him speaking into a tape recorder and having David Fischer shape it. “Both Syracuse graduates, the wannabe and the professional penman became the Yogi Berra and Whitey Ford of baseball authors,” writes Leeke.

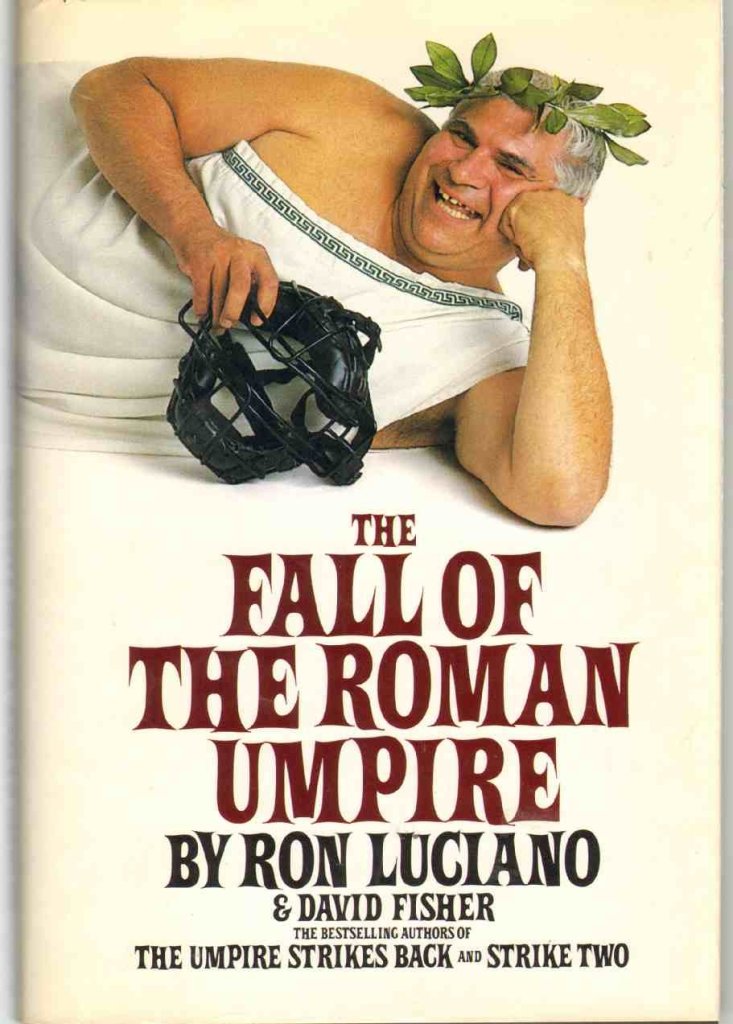

In order came: “The Umpire Strikes Back” in 1982; “Strike Two” in 1984; “Fall of the Roman Umpire” in 1986; “Remembrance of Swings Past” in 1988, and “Baseball Lite: The Funniest Moments of The 1989 Season” in 1990. The first book was excerpted twice, at 10,000 words each, in successive Sports Illustrated issues. He was on “The Tonight Show” with Johnny Carson and “Late Night With David Letterman.”

(Right about then, NBC had another idea: A new sit-com called “Cheers” was about to launch. The producers were looking for someone to play a dopey bartender named Coach/Ernie Pantusso. Luciano tried out for it. He didn’t get it. The show creators wanted a more experienced actor. It was also said, by Leeke, that Luciano’s resemblance to George Wendt may also have not helped.)

Funny stuff. Leeke certainly thought so during his meetup with Luciano during the book tour.

We assumed he was a sharp-witted observer of the game, a man who knew his literature and even once gave this quote about why he loved to write — it was because he loved to read.

“I don’t understand Shakespeare’s sonnets at all,” he said, “but I follow his tragedies. I like the mean characters, people like Macbeth’s wife. Hey, you’ve got to be a masochist to be an umpire, right?”

Apparently so, because with Jim Leeke’s new book we feel we have a somewhat better context to all this.

In the last dozen years, Leeke’s baseball-related titles have been about those who served in the military, including “The Gas and Flame Men: Baseball and the Chemical Warfare Service during WWI” in 2024; “The Best Team Over There: The Untold Story of Grover Cleveland Alexander and the Great War” in 2021; “From the Dugouts to the Trenches: Baseball During the Great War” in 2017; “Nine Innings for the King” in 2015; and “Ballplayers in the Great War: Newspaper Accounts of Major Leaguers in World War I Military Service” in 2013.

Leeke’s enduring curiosity about Luciano comes from having interviewed him in San Francisco during Luciano’s first book tour in ’82. Leeke heard even more stories and enjoyed them.

“Luciano Lore” is now how Leeke frequently refers to a tale told that maybe was too good to be true about the ump’s life because, well, there was enough embellishment after a few simple fact checks.

“Ronnie simply wanted to make people happy, and sometimes that required embellishing a story a bit,” said Fisher. “Actually, a lot. I mean, he told some whoppers.”

“He always wanted to amuse, certainly,” Leeke writes. “But his tales also cloaked a private gloominess that plagued Luciano much of his life. His motive for changing careers was simple, as Luciano admitted during his first season in baseball. ‘I’ve always been wrapped up in sports,’ he said. ‘Instead of teaching school at Endicott, N.Y., I decided to be an umpire’.”

Leeke wondered why it seemed Luciano was trying too hard to be liked. It stayed with him.

That’s tough to assess 30 years after Luciano died.

He was just 57 when he took his own life.

It was a purposeful exit as he had it all planned out.

His bouts of depression caught up with him as he tried to come off as bigger-than-life, but really uncomfortable living in the oversized body he was given. A size, he said, that could list him as “5-feet, 16-inches,” as he once joked. Again, that’s telling, as he was also in excess of 300 pounds and not happy with himself.

Maybe that explained some of his over-the-top existence. He was neither happy-go or lucky. The lulls of down time, the easy-to-slip-into drinking, the constant never-at-home travel, the toll it takes on diet and health. It led to feeling he had to toss himself out. Umpiring didn’t give him the same kind of a wins/losses experience he had as an athlete. He felt neutered in neutral.

Maybe there were some football head concussions that went undiagnosed. He checked himself into a hospital in ’94. But he came out. And he kept it all private, as those who did immediate investigation into his life uncovered.

Leeke wonders as much as he sorts out all kinds of potential reasons, mostly by reconnecting to three people who knew him best — book collaborator David Fisher, former umpire pal Dave Phillips and friend/handyman Rick Stefano. That’s about all Leeke had to lean into, aside from reading between the lines of Luciano’s previous books and frequent interviews he did with the media over the years.

Still, as Leeke points out, Luciano had been profiled over two dozen times by major newspapers, magazines and wire services, including the Los Angeles Times, Boston Globe, National Observer, People and Sports Illustrated. The New York Times Magazine did a 5,000-piece profile on him under the headline “The Likable Ump.”

“(He) probably drew more attention and had more written about him than any umpire in baseball’s long history,” wrote the Baseball Bulletin.

Many compared him to Max Patkin, the clown prince of baseball, except Luciano was part of the actual game played, and he generally had high scores for his accuracy. It was just his showmanship overwhelmed that aspect of his legacy — remembered as the guy who chased Weaver from games 54 of the 98 times it happened to the Baltimore Orioles’ manager, much of it as part of the gamesmanship they both had.

By the end of Leeke’s tidy research project, we really aren’t left with much more to go on. Just, maybe a new way of re-reading all those previous Luciano books, because after finishing this one, it all just seems to empty.

Something none of us left seem to be able to properly tackle.

How it goes in the scorebook

Unlucky Luciano is too easy, too dismissive of a way to classify this.

It’s a reminder of the Charlie Chaplin song, “Smile.”

What this book also reminds us is that, even if Luciano wasn’t the first, he was certainly not the last to try to normalized umpire autobiographies (most often with ghost writers).

It didn’t then, and it doesn’t now, feel quite right.

Of course, as human beings doing their best at their jobs, they are entitled to their views. In print? Weren’t the best umpires supposed to be neither seen nor heard from unless the moment required it? Why the tell-all stuff later?

A biographer, like Leeke here, can do a much more honest assessment.

The umps who did recount their lives did it after they were done, including Dave “Life Behind The Mask: My Double Life in Baseball” Pallone (1990), Pam “You’ve Got to Have Balls to Make It in This League” Postema (1992), Durwood “You’re Out and You’re Ugly, Too!” Merrill (1998), Ken “Planet of the Umps” Kaiser (2003), Dave “Center Field on Fire” Phillips (2004), Bruce “As They See ‘Em” Weber (2009) and Al “Called Out But Safe” Clark (2014). All of these were done after Luciano’s run of books and all are cited in Leeke’s bibliography.

Those before Luciano start with Jocko Conlin (1967) and Tom “Three And Two!” Gorman (1979), while more after included Doug “They Called Me God” Harvey (2014) and Dale “The Umpire Is Out” Scott (2022).

These all feel like a Supreme Court justice spilling personal feelings about his or her job on how they were an impartial observer, but whatever interesting they might want to say would surely poison the court of public opinion about their ability to be objective. Current Supreme Court chief John Roberts recently said he enjoys keeping a somewhat low profile and he has no plans to write an autobiography.

“My life is very interesting — to me,” he said. “I’m not sure it’s terribly interesting to anyone else.”

You can look it up: More to ponder

== A review by Charlie Bevis for BevisBaseballResearch.com, scoring it a rather low L2C3R2: “Leeke soft-peddles … Luciano Lore rather than term him a fabulist. While Leeke does sort out the facts and fables of the jolly arbiter’s life … Not until the very end of the book does Leeke delve into a few possibilities that might have elevated Luciano’s disguised depression into suicidal action. … The depression-to-suicide topic could have been explored through expert-author research in the mental health field to provide an interpretation of the underlying “gloominess” in Luciano’s life. This was a missed opportunity to develop a cultural issue to infuse throughout the book, which would put Luciano’s life into greater context and provide more intellectual depth to the “unruly” sub-title of this biographical story. Additionally, it would add the tension and conflict elements of good narrative non-fiction writing. … This book, though, is more of a popular history of Luciano’s life with academic documentation, rather than an intellectual inquiry into how his life was negatively impacted by unsuspected cultural and societal forces. The definitive biography of Luciano remains to be written.”

Not sure I agree, but it’s an interesting thing to point out. The publisher often dictates the trajectory of the project as well as the author. Was this meant to be an academic pursuit? A collection of quips and clips culled from sources to see where it lands? What’s wrong with a “popular history” project? That’s what Luciano was, and remains, and now we have more understanding.

== Leeke, who also did the 2022 SABR bio project story on Luciano, wrote in a recent University of Nebraska Press blog that Loosh “would’ve absolutely hated the idea” of Automated Ball-Strike System even thought he was “no hidebound traditionalist.” He “embraced” the designated hitter in the AL and could see the way with video replay was going to be part of a game-stoppage to reassess a call on the field.

“But Ronnie would have detested ABS for removing one element of human judgment from the game. Big, loud, and entertaining, a former All-America football tackle, he often lamented the monochromatic nature of modern umpiring. Some writers refer to the new ABS now as a “robo-ump,” a term that umps and the powers-that-be both dislike. When ending his MLB career in 1980 to become a TV color analyst, Ronnie commented that many umps in fact trained themselves to perform like robots. This kind of behavior didn’t suit his personality. “I’m a fan,” he said. “I can’t live the game? Then hire a robot.”

Leeke then recounted a story he had in his book about how, in 1975, Luciano reversed a call on a home run/foul ball concerning a long fly the California Angels’ Tommy Harper once hit down the third-base line in 1975 in Baltimore. “Diogenes, the mythical Greek who spent his life searching for a completely honest man, could have found one in the umpires’ dressing room,” The Sporting News said afterward, referring to Luciano’s public mea culpa.

== A Tyler Kepner column in The Athletic recently focused on 44-year-old umpire Mark Ripperger, whose high school baseball career in Escondido led him to a place calling balls and strikes in Major League Baseball since 2010. He just recently scored a “perfect game” according to the Umpire Scorecards website, calling all 136 pitches made in a Kansas City-Minnesota game correctly. It stands as just the second perfect game in the 11 years of Statcast data. The other was by Pat Hoberg in Game 2 of the 2022 World Series in Houston.

== Congrats again to Larry Gerlach, whose 2024 book, “Lion of the League: Bob Emslie And the Evolution of The Baseball Umpire” won the 2025 SABR Seymour Medal presented at the NINE conference in Tempe, Ariz., last March.

Gerlach, who also wrote “The Men In Blue: Conversations with Umpires” in 1994 and “The SABR Book of Umpires and Umpring” in 2017, is the expert in this field. Here’s our review of “Lion of the League” from last year’s series with this assessment: “This book rules. Umps may feel they have thankless jobs. It may have been a somewhat thankless task that Gerlach proceed with this project. But the result is a clear documentation that gives readers and fans of the game better context not just of the position’s evolution, but of its importance, and how someone like Emslie could make a living out of it and keep a profile under the radar from most media reporting. This book may be much thicker than a standard MLB rule book. But it’s justified. If it was just a bio on Emslie, it would have been enough. But context and history and all sorts of things were needed research by Gerlach to achieve this.”

A bio of Cal Hubbard (1976) and Bill “Dean of Umpires” McGowan (2005) are also noted for their worthiness. Bios on Emmett Ashford (2004) and Augie “Stalag Luft VI to the Major Leagues” Donatelli (2011) are also in the mix. Consider digging into the lives of Tom Connolly and Bill Klem, the first umps voted into Baseball Hall of Fame in the 1950s, for their life stories.

== Another recent story in The Athletic: The MLB made a change to the strike zone that actually tightened it up — it was part of a new labor agreement with the Major League Umpires Association, significantly decreased the margin of error for umpires in their evaluations — but no one had given the players a heads up on it. So while there are fewer called strikes off the edges of the plate thus far in 2025 through the same point as last season, it’s because “everybody’s zone has shrunk,” Angels catcher Travis d’Arnaud told The Athletic. “Every (umpire) across the league.” How does that happen?

1 thought on “Day 19 of 2025 baseball book reviews: Unlucky Luciano’s last out”