This is the latest post for an ongoing media project — SoCal Sports History 101: The Prime Numbers from 00 to 99 that Uniformly, Uniquely and Unapologetically Reveal The Narrative of Our Region’s Athletic Heritage. Pick a number and highlight an athlete — person, place or thing — most obviously connected to it by fame and fortune, someone who isn’t so obvious, and then take a deeper dive into the most interesting story tied to it. It’s a combination of star power, achievement, longevity, notoriety, and, above all, what makes that athlete so Southern California. Quirkiness and notoriety factor in. And it should open itself to more discussion and debate — which is what sports is best at doing.

The most obvious choices for No. 12:

= Vlade Divac, Los Angeles Lakers

= Charles White: USC football

= Dusty Baker: Los Angeles Dodgers

= Tommy Davis: Los Angeles Dodgers

= James Harris: Los Angeles Rams

= Juju Watkins: USC women’s basketball

= Dwight Howard: Los Angeles Lakers

= Todd Marinovich: Los Angeles Raiders, Los Angeles Avengers

The not-so-obvious choices for No. 12:

= Pat Riley: Los Angeles Lakers

= Gerrit Cole: UCLA baseball

= Denise Curry: UCLA women’s basketball

= Joe Namath: Los Angeles Rams

= Randall Cunningham: Santa Barbara High football

= Jeff Kent: Los Angeles Dodgers

The most interesting story for No. 12:

Richard Nixon: Whittier College football offensive tackle (1930 to 1933)

Southern California map pinpoints:

Yorba Linda, Fullerton, Whittier, San Clemente

From Richard Milhous Nixon’s perspective of own his life and legacy, victories were unimpeachable.

History notes he did lose the 1960 Presidential Election (even it was by just 0.17 points in the popular vote). And he lost the 1962 California governor’s race by five points. But that wasn’t going to define him — or let anyone kick him around in the public arena.

His greatest comeback was the 1968 election to become the 37th President of the United States. It was followed up by a landslide re-election in 1972, winning by nearly 18 million votes.

Nixon went into his “V” formation, both hands flashing triumph for all it was worth.

During those four-plus years as the commander in chief, Nixon was also obsessed with not being the one pinned with losing the Vietnam War.

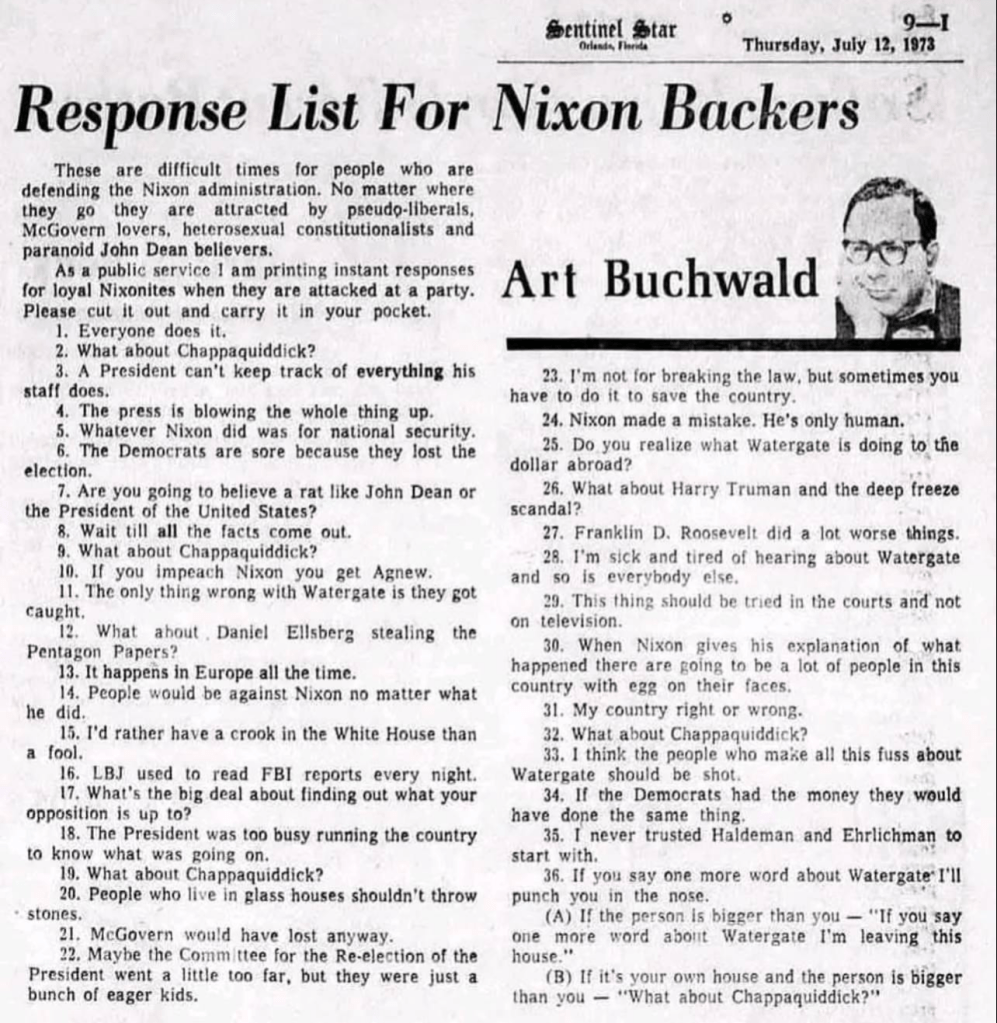

But then there’s the old sports adage: If you’re not cheating, you’re not trying.

That line of demarcation for sportsmanship led to him forfeiting the most powerful position in the world. A devastating defeat that became the lede to his obituary.

Where did the win-at-all-costs philosophy come from?

Consider the frustrated athletic career he had first at Fullerton High and Whittier High, leading into a highly influential period on the Whittier College football team, capped off by wearing No. 12 his senior year.

Nixon believed in the words and actions by a football coach known as “Chief,” a commanding voice that taught him all about the importance of how the games are played, how to win, and also even lessons on how to take a loss and make it a teachable moment.

Nixon hated losing. Perhaps, to his determent. Sports played a part in that journey.

Born on a lemon ranch in Yorba Linda in 1913, Richard (given the name by his parents after Richard the Lionheart) was 12 years old when a spot was found on his lung and there was a family history of tuberculosis — an older and younger brother died from it.

Richard Nixon was told not to play sports. Even thought the spot turned out to be scar tissue from an early bout of pneumonia.

Growing up among those Nixon would eventually refer to as “forgotten Americans” and the “silent majority” of hard-working church folks just chasing a dream, he was drawn to try out for JV football at Fullerton High. When he then transferred closer to home at Whittier High at the start of his junior year, he ended up as a student manager for the athletic teams. At Whittier High, he ran for class president but lost to a candidate he would describe as “an athlete and personality boy.”

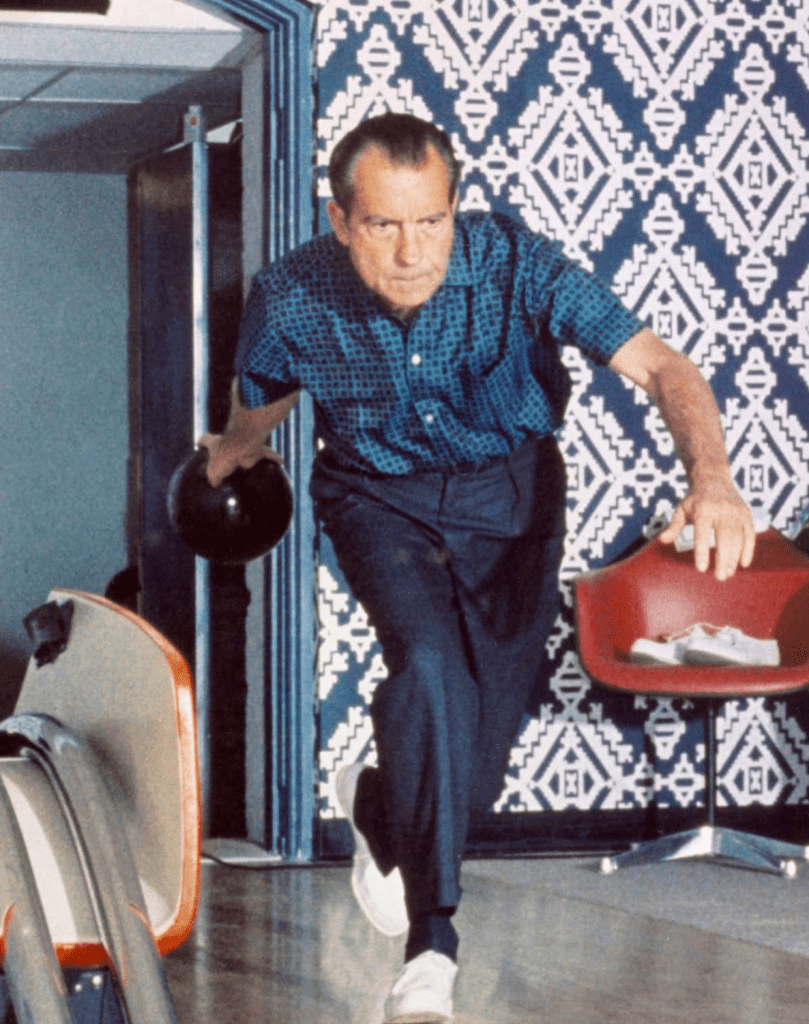

With the start of the Great Depression in 1930, Nixon didn’t pursue college at Harvard or Yale, but stayed closer to home at Whittier College, pursing a history degree. While he played basketball and football, and also tried out for track and baseball, his victories were celebrated on the debate team.

Poetry in motion may not have been the nickname that best fit Nixon while playing any sport for the Whittier College Poets, the NCAA Division III private school east of Los Angeles and founded in 1887, nicknamed after Quaker poet John Greenleaf Whittier.

If only he was a spry triple-option quarterback, or deceptive point guard, Tricky Dick would have fit. His athletic career was more a limerick than lyrical.

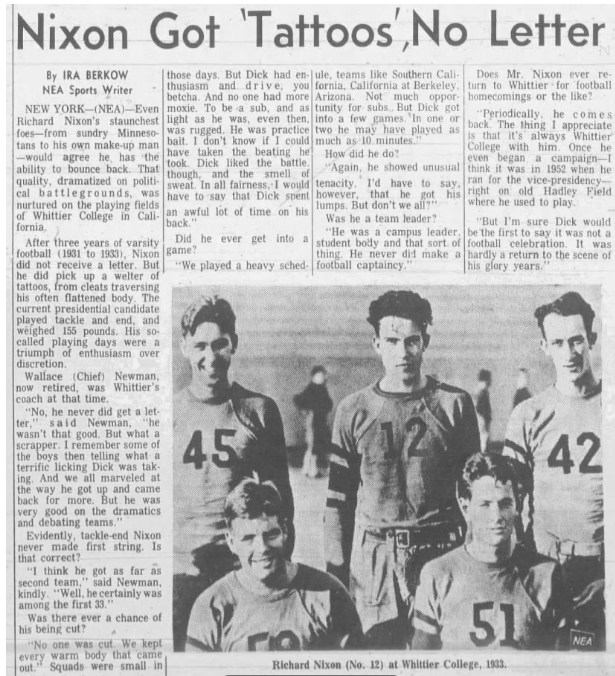

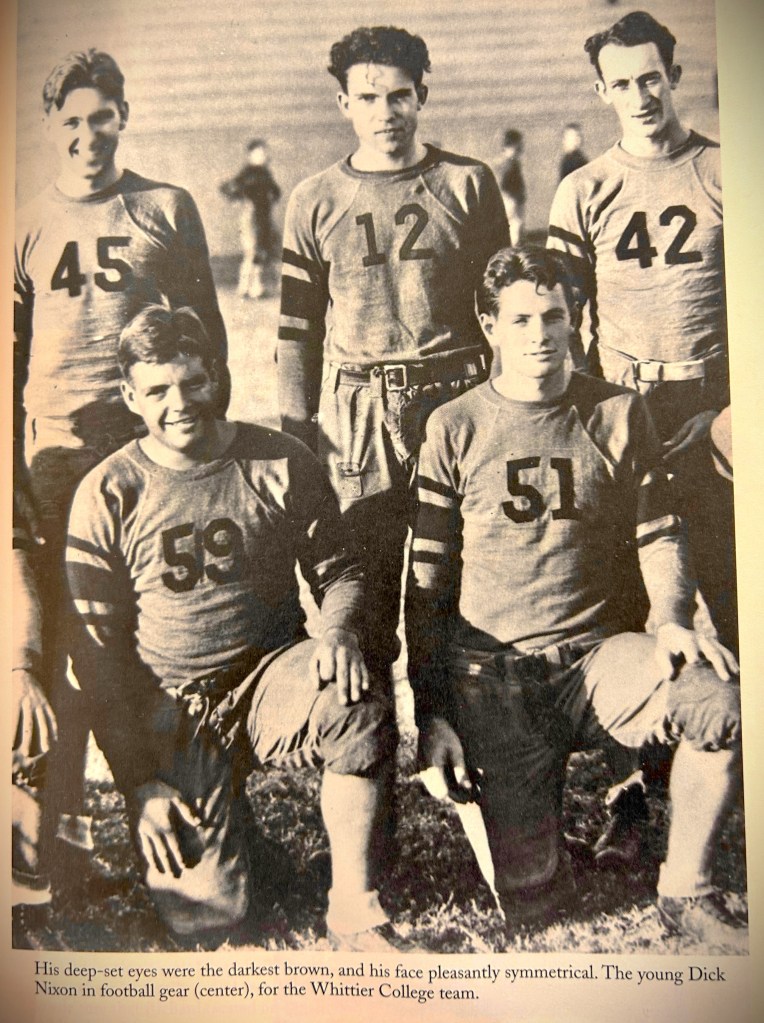

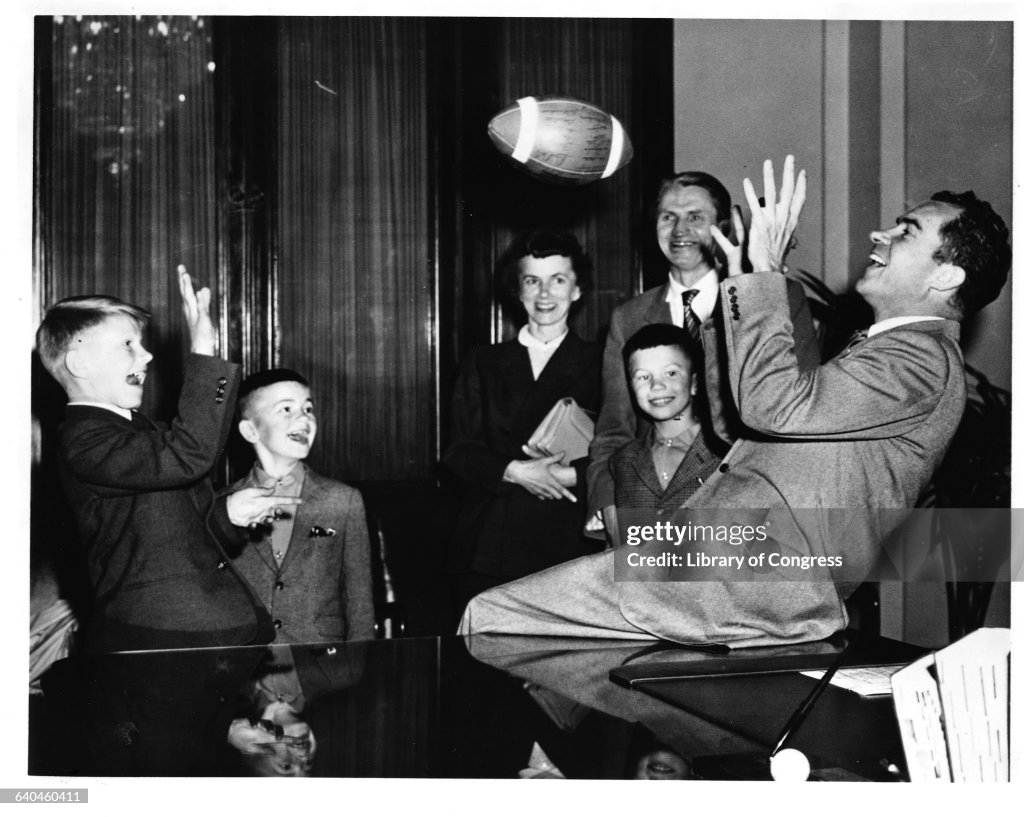

Various team photos in circulation during his time at Whittier shows he wore No. 12 a senior after sporting No. 23 in earlier years. It was a huge step up from being thought of just a team manager.

In the 1,120 page “RN: The Memoirs of Richard Nixon” in 1978, one of 10 books he wrote, mostly about himself, Nixon explained on page 19:

“My happiest memories of those college days involve sports. In freshman year, I played on the Poetlings basketball team, and we had a perfect record for the year: We lost every game. In fact, the only trophy I have to show for having played basketball is a porcelain dental bridge. In one game, jumping for a rebound, a forward from La Verne College hit me in the mouth with his elbow and broke my top front teeth in half.”

In the 1990 book, “Richard Milhous Nixon: The Rise of An American Politician,” author Roger Morris noted that Nixon also participated in track but “he often finished fifty yards behind the rest of the runners.”

As a freshman, Nixon said he once took charge of the traditional bonfire rally prior to the varsity game against Occidental College. He drove his parents’ old grocery truck through town alleys finding old wood and crates to create the fuel for the fire.

Nixon wrote that two factors motivated his interest in sports: Relief from every-day life of work and study, and fulfilling his highly competitive instinct.

“Ever since I first played in high school, football has been my favorite sport,” he wrote. “As a 150-pound 17 year old freshman (in college, as he was a year younger than most, having skipped a grade in elementary school), I hardly cut a formidable figure on the field, but I loved the game — the spirit, the teamwork, the friendship. There were only eleven eligible men on the freshman team, so despite my size and weight I got to play every game and wear the team numeral on my sweater. But for the rest of my college years, the only times I got to play were in the last few minutes of a game that was already safely won or hopelessly lost.”

It was noted by some that Nixon came from “good Quaker stock” and was “a very aggressive individual.”

Former Whittier player John Arrambid once said of him: “I can remember (Dick) on the ground most of the time, but we’d pick him up and he’d be ready for the next play. That’s what we admired about him. He never got into a ball game, but he was there and took it every week.”

Listed at one point as 5-foot-11 and 145 pounds, Nixon was described by author Evans Thomas in the 2015 book “Being Nixon: A Man Divided” as someone “undersized for a tackle, but he was too uncoordinated and slow-footed to play in the backfield. Mostly he was used as cannon fodder for the first team at practice and sat on the bench during the games.”

One teammate said: “Anyone who could take the beating he had to take, the physical beating, was brave.”

By the time he grew into a 176-pound tackle on a senior squad that finished 10-1 and won the Southern California Intercollegiate Athletic Conference (SCIAC), Nixon said he understood the important lessons learned from his coach, Wallace Joe “Chief” Newman.

Newman had been an All-American and three-year tackle at USC, playing in the Trojans’ first Rose Bowl appearance in 1923, a 14-3 win over Penn State. It was also the first Tournament of Roses football game held at the newly built Rose Bowl Stadium in Pasadena.

From his 1990 memoir, “In the Arena: A Memoir of Victory & Defeat & Revival,” Nixon wrote in Chapter 7 titled “Struggle”:

“Next to my father, the man who influenced me most was my coach. I was not a good athlete. I went out for football, basketball, baseball and track and never made a letter. But I learned more about life from sitting on the bench with Chief Newman than I did getting A’s in philosophy courses.

“He taught us how to win. You don’t win by playing as well as you think you can. You win by playing better than you think you can.

“He taught us how to lose. He never repeated that tired refrain, ‘It’s not whether you win or lose but how you play the game.’ We must always play to win but accept that sometimes we lose. When we lose, we should get mad — not at the other team but our ourselves for not playing better.

“He taught us now to come back. We must never accept defeat. No matter now many times you get knocked down, get up and don’t let it happen again.

“He drove us to overachieve. I can never remember a time when the Chief congratulated a great player for playing a good game, since the player was only doing what he was capable of doing. but he was always hard on those who did not play up to their capability.

“In a sense, he taught me a lot about humility. Because I worked hard, I was better than average in academic subjects. The face that I was lower than average in sports reminded me that no one should get a swelled hear because of what he achieved in his field, since there are always others who are far better than he is in their fields.”

Nixon also noted how Newman was ahead of his time in the civil rights movement. That was a result of playing at USC when Bryce Taylor, one of the first Blacks ever at the school, was discriminated against at a nearby campus restaurant.

“He not only talked a good civil rights game, he lived it,” wrote Nixon of Newman, who was enrolled with the La Jolla Band of Luseno Indians and the Mission Creek Band of Mission Indians and someone Nixon considered for a post as the Commissioner of Indian Affairs during his presidency.

“He never asked for respect because he was an American Indian. The fact that he was one of the best players of his time at USC earned our respect. He treated the two fine black player on our squad exactly the same as the white ones … Under Chief, no one was entitled to better treatment because he happened to be black. There was never a hint of racism on that team. This was perhaps in part because Whittier, though non-sectarian, had a Quaker background. But it was also because we knew that if any of us got out of line by failing to keep our grads up, by not playing up to par, or by mistreating someone else because he happened to be black, we would be kicked off the squad.”

Nixon expanded on that story with a story from “In The Arena” from his senior year at Whittier College, when he did not make the traveling squad but drove to Tucson, Ariz., for the final game of the season at the University of Arizona.

“When I arrived, Chief took me aside and told me he had learned the hotel dining room did not serve blacks. He was livid but did not want to create an incident before the game. He gave me three dollars and asked if I could discreetly invite Bill Brock, our black all-conference fullback, to join me for a steak dinner in one of the good restaurants in town. We must have handled the situation well because when Bill came to see me in San Clemente in 1976, he told me that he remembered the dinner but had never been able able to figure out why I had invited him.”

Nixon referenced a Whittier-San Diego State game during his sophomore year when he saw Warren lose his temper. Whittier trailed after the first three quarters but “made a sensational comeback for an upset win.” As Warren gave instructions to Whittier linebacker Bryon Netzley in the fourth quarter, Nixon said Warren hadn’t noticed the Netzley was running in place on top of Warren’s hat that he earlier threw to the ground in frustration.

“Chief was a very serious man, but he broke out in a huge laugh” when he saw what happened, Nixon wrote. “From that time on, he never lost his temper in a game.”

Newman’s teams would have success. In 1932, in a season when the Poets finished 10-1, Nixon was listed as the team’s starting left tackle in its October 28 victory over the 160th Infantry team. In Nixon’s senior year of 1933, it included a 51-0 loss to USC before some 35,000 at the Coliseum. That Howard Jones-coached Trojan team had eight shutouts and an eventual No. 6 national ranking.

Nixon nearly quit his senior year, but Newman convinced him to stay in the program. Teammates recall how Nixon often was vocal with referee calls from the bench, showing some support and pointing out when the opposing team was committing penalties that weren’t called.

“See some underhanded act on the field, and no one could yell louder than Dick,” said teammate Edwin Wunder, who also heard the student body chant — “Put Nixon in! Put Nixon in!” — when a game got out of hand. When Nixon did get in, he would be so enthusiastic other teammates recall it was difficult to keep him from jumping offsides.

After serving eight years at Dwight Eisenhower’s vice president starting in 1953, Nixon officially kicked off his first campaign for president in 1960 on the same football field he once played on at Whittier, before 20,000 roaring supporters. When he accepted the Republican nomination for president in 1968, Nixon thanked Newman, who ended up with a 102-66-14 record as the Whittier football coach from 1929 to 1950.

In “Richard Nixon: The Life,” author Farrett wrote on page 63: “Newman fueled Nixon’s ache for winning at almost any cost.” Newman had described Nixon as “a scrapper … Dick had enthusiasm and drive … no one had more moxie. Dick liked the battle and the smell of sweat.” He also said of Nixon: “If he could have run well, we could have used him. Dick was a pretty awkward kid.”

Teammate Gail Jobe said it in “Richard Milhous Nixon: The Rise of An American Politician“: “Guts. I’ll say that for Nixon. He had guts.”

The Whittier team waterboy, Harold Litten, recalled in a 1955 Boston Globe story about how then-Vice President that Nixon was uncoordinated and “had two left feet” but he was still showing leadership: “Boy, was he an inspiration! He was always talking it up. That’s why Chief let him hang around. He was one of those inspirational guys every team needs.”

For Nixon, the fact his father, Frank, came to watch practices regularly also fueled his desire to succeed and make him proud.

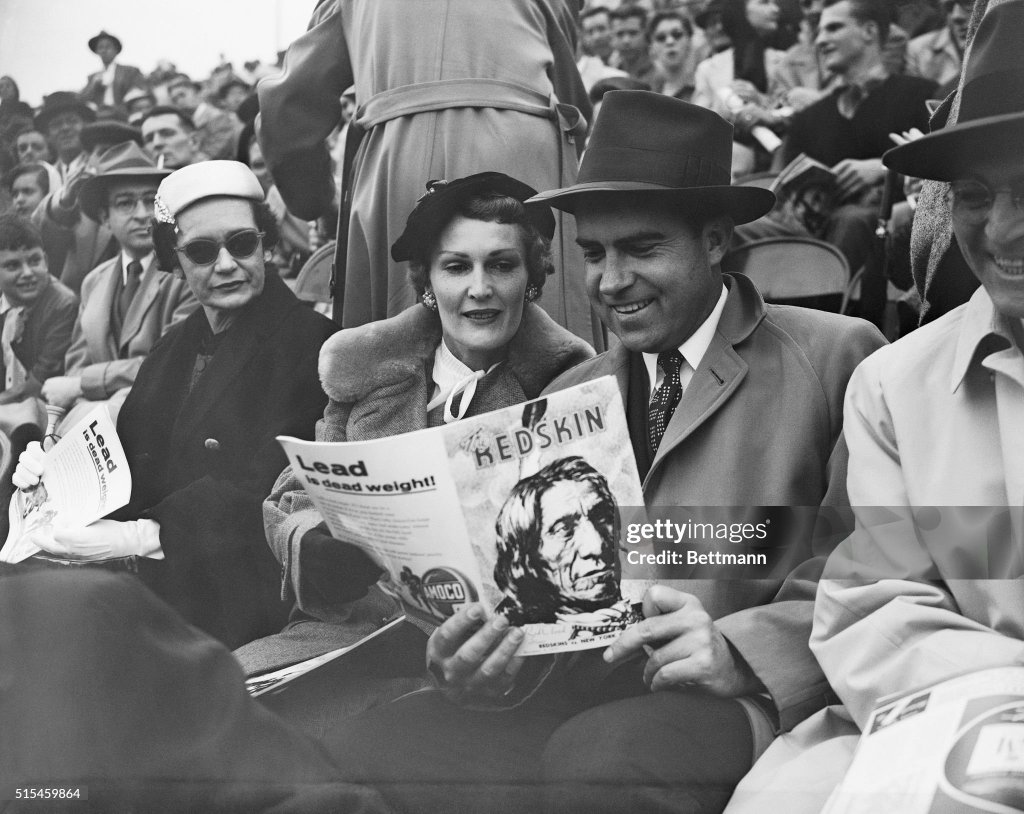

During the 1950s, Nixon often mused about what kind of career he could have had as a sportswriter. As a fan, Nixon talked such a good game that “even some life-long Democrats were promising to vote for him” against John F. Kennedy, wrote Football News, after Nixon spoke to the Football Writers’ Association in 1959.

From a story posted on Slate.com about Nixon’s affection for the game, it included: “The fans loved him. Toward the end of the games in which the Poets were losing badly, the fans would chant: We want Nixon! Put Nixon in!’”

Newman was quoted in the same story: “We used Nixon as a punching bag. If he’d had the physical ability he’d have been a terror.”

By the time that Nixon attended Duke Law School in 1934, any fancy dreams about a future in sports took a back seat, but he could retain a competitive drive from that sporting experience.

Nixon somehow was inducted into the Whittier College Purple And Gold Athletics Hall of Fame. Later, the school added one-time Poets football coach George Allen, who got his start there in 1951 when Newman retired and lasted until 1956, two decades after Nixon was a student. Allen, the Los Angeles Rams’ head coach from 1966 to 1970, ended up coaching the Washington Redskins from 1971 to 1977, overlapping the years Nixon was in the White House, and the two enjoyed their Whittier connection.

“I don’t know anyone who attended Whittier College and did not come out a better person,” Allen said during his college induction ceremony in 1989.

One of Nixon’s other famous gridiron-related exploits while in office include his calling in a play to Miami Dolphins coach Don Shula in 1971 — famously resulting in a 13-yard loss.

Also in the hour of audio tapes Nixon recorded in the Oval Office, there was also a tirade about NFL TV blackout rules.

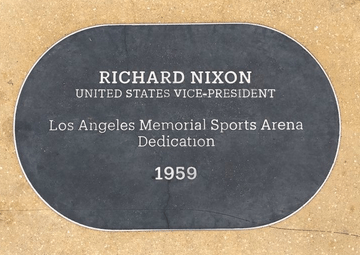

One more Nixonesque-sports connection can be found from something he did in 1959. On Exposition Park Drive just west of Figueroa Street, on the sidewalk along the north side of the current BMO soccer stadium, a plaque commemorates that day when, on July 4, 1959, then-Vice President Nixon dedicated the Los Angeles Sports Arena site as a memorial to U.S. Armed Forces Veterans. The arena stood until it was demolished in 2016.

Although never a boxer, Nixon was said to have a “rocking, socking style of campaigning.” Through every aspect of his political career, dots can be connected to the football-related jargon Nixon used during speeches or committee hearings, savoring stories of how he had befriended Allen and shared football strategy — perhaps suggesting a play or two to use in a Super Bowl.

In the three-hour PBS series “American Experience,” it was noted that Nixon “loved the movie ‘Patton’ and watched it again and again at the White House. General Patton was a man of action, contemptuous of his critics, uncompromising, determined to win at all costs.” There was also a clip of George C. Scott in the character of General George Patton saying: “I want you to remember Americans love a winner and will not tolerate a loser. Americans play to win at all times … That’s why Americans have never lost and will never lose a war because the very thought of losing is hateful to Americans.”

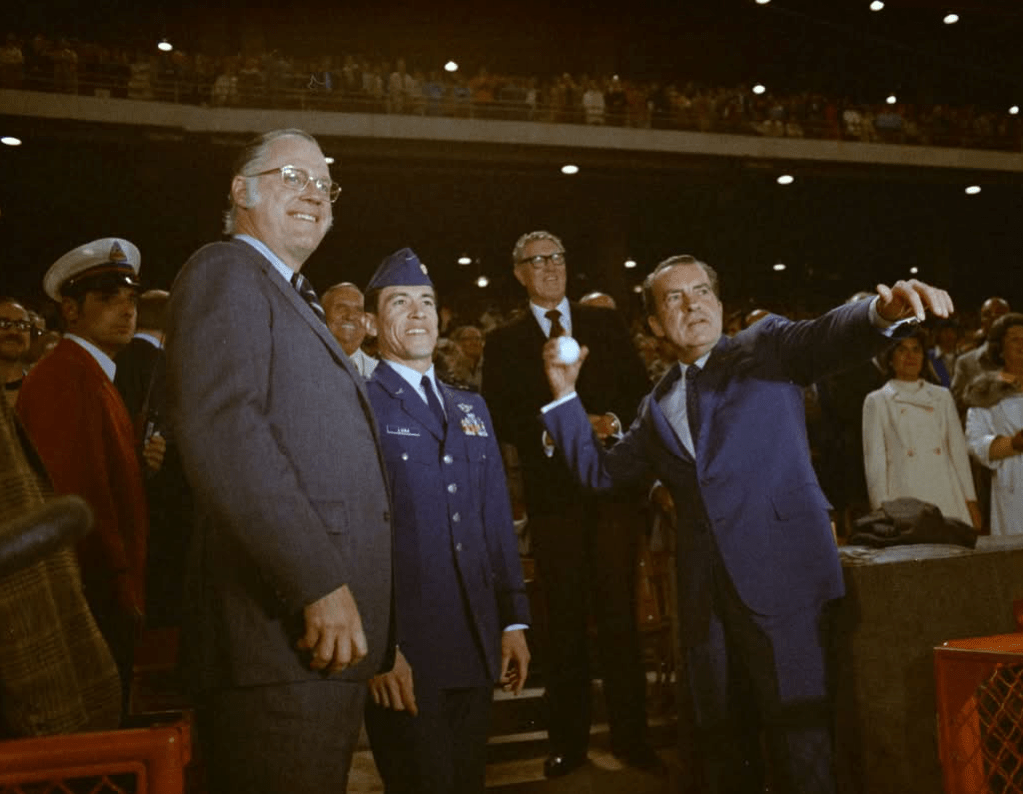

Even with all the differences Nixon had with gonzo journalist Hunter S. Thompson, at least they could bond over football enough that it didn’t drive either of them mad. Even if Nixon never received a varsity letter for playing football, the Nixon Foundation put forth the narrative that he was “football’s No. 1 fan.”

There was also his famous quote after he lost the 1962 California governor’s race: “You won’t have Nixon to kick around anymore.”

Nixon recalled once his favorite sports writer were Braven Dyer, Bill Henry and Paul Zimmerman. “To read today’s drab, statistics-laden sports stories after watching a good game on television is like eating warmed-over hash,” he wrote for “In the Arena” in 1990, four years before his death.

Sportswriter Robert Lipsyte remembered that the only time he found Nixon “even vaguely sympathetic” was while watching him reminisce at a football banquet about games from the 1930s. Nixon argued that football’s values were good for the nation and enjoyed invoking football metaphors.

“What does this mean, this common interest in football, of presidents, of leaders, of people generally? It means … the character, the drive, the pride, the teamwork, the feeling of being in a cause bigger than yourself,” he told the National Football Foundation in 1969.

A story in Grantland recalled that, in 1969, Nixon even took on the “self-anointed role in choosing a national champion.” That December, when No. 1 Texas faced No. 2 Arkansas, Nixon was at the game and had a plaque ready to declare the winner as “the unquestioned No. 1 in the land.” The story added that a few weeks earlier, Nixon “marked the occasion of a 250,000-person anti-Vietnam rally outside his home by staying indoors and watching Ohio State beat Purdue by four touchdowns.”

Nixon apparently “did not foresee the political thicket into which he’d wandered,” as Joe Paterno’s Penn State team, sitting undefeated in its last 29 games, was also worthy of consideration for this mythical national title, according to the thousands of letters and telegrams that poured into the White House from Pennsylvania natives,” the Grantland story recalled, as well as a few Penn State alums actually picketing the White House.

“Presidents entangle themselves with sports to political ends all the time, but never had there been such a direct and unambiguous declaration from a chief executive as the one Nixon made by inserting himself into the ’69 game,” the story added. “Any real opportunity Penn State had to capture the national championship, beyond a Texas loss in its bowl game, had essentially been quashed.”

After Texas beat Arkansas, 15-14, Nixon addressed the National Football Foundation and Hall of Fame banquet and shaded his opinion to say Penn State should be considered for the title, but he added in his closing remarks: “I think Texas deserved to be No. 1.”

At a June 1972 White House press conference, RKO General Broadcasting reporter Cliff Evans asked the president to name his favorite baseball players. Nixon quickly named a few, but stopped when faced with the prospect picking between legendary players. Pressing the issue, Evans asked in a follow-up: “Mr. President, as the nation’s number-one baseball fan, would you be willing to name your all-time baseball team?” The honorary member of the Baseball Writers’ Association readily agreed and made his selections at the Presidential retreat, Camp David, enlisting the help of son-in-law David Eisenhower. White House Press Secretary Ron Ziegler distributed the list through the Associated Press with the president’s name on the byline for publication in the Sunday papers in early July.

Instead of producing a single all-time all-star team roster, Nixon selected a pre-war and post-war team for each league, didn’t limit it to nine men, and only picked players after 1925, the year he started to follow baseball, and stopped at 1970 to give his evaluations some perspective.

In 1992, Nixon made another update of his All-Star Teams. Baseball-Reference.com created a post about it all.

The most prominent critic of Nixon’s baseball teams was the New York Times Red Smith, who claimed the piece was poorly-written and “cliché-ridden,” and also questioned some of Nixon’s selections. Nixon also was met with numerous tough-and-cheek teams and parodies of his choices. The Gary Post-Tribune listed Nixon as a pitcher who “possesses a great curve ball and has licked early control problems.”

Nixon wrote in his book “In The Arena” about how he declined an invitation to the 1976 Rose Bowl game in Pasadena two years after his ’74 presidential resignation

“(Ohio State coach) Woody Hayes called me before the game and promised to bring the game ball,” Nixon wrote. “When Ohio State lost (the No. 1 Buckeyes dropped a 23-10 decision to Dick Vermeil’s UCLA team), he was so depressed that he canceled the trip (to San Clemente) and feared his glum mood would depress me as well. We did some Monday morning quarterbacking on the telephone instead.”

New York Times columnist Russell Baker once wrote of Nixon: “There were darkness in his soul that seemed to leave his life bereft of joy. He was a private, lonely man who never seemed comfortable with anyone, including himself, a man of monumental insecurities for whom public life, I thought, must be a constant ordeal.”

If true, maybe there is some empathy to save for the Nixon who, by all appearances of that Whittier team photo, or attending a game in the stands, or being in a group of people where a football was present, seemed to enjoy the experience that sports allowed him to have.

In the book, “The Rise of An American Politician,” Whittier teammate Wood Glover surmised that Nixon stayed on the football squad so long despite little play because “he just enjoyed the game. He enjoyed being around it. I think he liked the contact with those people. And I’m not too sure that he didn’t enjoy it most than he did with just the scholar type, because I think he was challenged from a different standpoint. You know, the athletes don’t give a hoot about what they say or when they say it … and I think Dick enjoyed the comradeship and the straightforwardness.”

Nixon biographer Morris added: “He found among the football team, even apart from their locker room bull sessions, the candor and freedom from artifice that he had seen in his father, and that was missing in much of the rest of his universe. If the Milhouses were a tribe of quiet, compelling women, if debate and academics demanded subtlety and maneuver, the football team was a world of men and a kind of raw honesty.”

In the September issue of the Atlantic, veteran political writer Clark Hoyt, a Pulitzer Prize–winning journalist who served as public editor/ombudsman for The New York Times, started a story: ”

“On a hot, drizzly Friday in August more than 51 years ago, I stood with other reporters on a temporary riser outside the East Wing of the White House. There, we watched as a disgraced Richard Nixon climbed the stairs to a presidential helicopter, turned at the doorway, extended his arms in a bizarre victory salute, and flew off into history.”

Claiming victory of some sort?

“Recall how Watergate unfolded. Burglars paid by the Nixon reelection campaign bugged telephones at the Democratic National Committee headquarters in Washington’s Watergate complex. They were caught in the act after a night watchman discovered tape over a door latch and called the police. The scandal broadened and climbed, revelation by revelation—much of it through the reporting of journalists, The Washington Post’s Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein. A bipartisan Senate Watergate Committee was formed and held hearings, trying to find the truth. It was a Republican senator, Howard Baker of Tennessee, who kept asking two key questions: ‘What did the president know, and when did he know it?’ A witness revealed that there was an Oval Office taping system that recorded the conversations there. A unanimous Supreme Court ordered Nixon to turn over the tapes to a special prosecutor appointed by his own Justice Department. The president, having previously refused, then complied. A ‘smoking gun’ tape revealed Nixon had plotted to block investigators as he campaigned for reelection. The leaders of his own party in Congress went to the White House to tell him that he was almost certainly going to be impeached and convicted. And Nixon was soon on that helicopter leaving office. …

“As a reporter, I sat in Judge John Sirica’s courtroom and listened to the first public airing of the Watergate tapes, in which an angry, profane Nixon declared to his top aides, ‘Well, the game has to be played awfully rough’.”

At what price?

“The judgment of history,” Nixon had once said, “depends on who writes it.”

Whomever writes about Nixon’s thirst for wins and disdain for losses, consider how sports, and his frustrating relationship with them, planted those seeds.

Who else wore No. 12 in SoCal sports history? Make a case for:

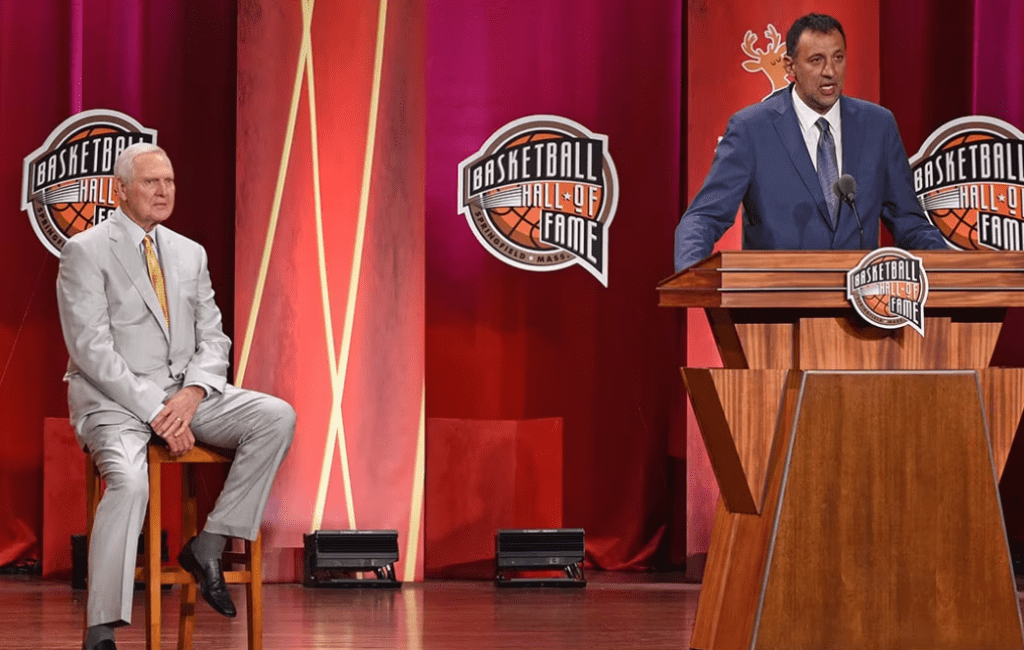

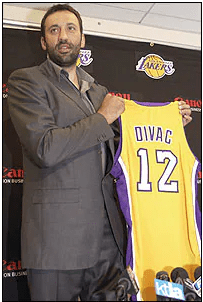

Vlade Divac: Los Angeles Lakers center (1989-90 to 1995-96; 2004-05):

Best known: The 7-foot Serbian canary in the NBA’s Euro-talent coal mine proved it was more than OK assimilate into the dominant American game, but also influence change in it. Without him, is there no Pau Gasol, Dirk Nowitzki, Giannis Anteokounmpo or Luka Doncic? Without Divac, do the Lakers even know Kobe Bryant as an L.A. legend? Lakers general manager Jerry West, who brought Divac into the NBA world for a purpose, found him to be the ultimate trade bait for Charlotte to take him in exchange for the rights to the then-18-year Bryant in a a deal announced just after the 1996 draft.

In 16 NBA seasons – half with the Lakers, including his first seven – Divac logged only one All-Star selection (with Sacramento), averaged a modest 11.8 points, 8.2 rebounds and 3.1 assists. He is top 60 in NBA’s 75-year history in rebounds. Also top 35 in career blocks. Yet he has a Basketball Hall of Fame bio that reads:

The arrival of Vlade Divac in the NBA in 1989 signified a watershed moment for the game of basketball. Divac, barely out of his teens and barely speaking a lick of English, landed in Southern California, the 26th draft pick of the Los Angeles Lakers and the new face of international basketball. Just the summer before, Divac had helped Yugoslavia to a silver medal at the 1988 Olympics. Now the big center with the soft hands, perfect timing, and warm heart would blaze a basketball trail for Europeans and eventually other players from across the globe. Divac won gold at the 1990 and 2002 World Championships to accompany gold at the 1989 and 1991 European championships. His game was beautiful – the effortless passes, the flawless footwork, the up-and-under for an easy layup, and the clever practice of defending an opponent with the so-called flop. Divac recorded more than 13,000 points, 9,000 rebounds, 3,000 assists, 1,600 blocked shots, and 1,200 steals making him one of the greatest all-around players to come from Europe to the NBA.

Not well remembered: The Sacramento Kings retired Divac’s No. 21, back in 2009. His No. 12 jersey has yet to be retired by the Lakers, despite his Hall of Fame status. Who’s willing to take the charge for that?

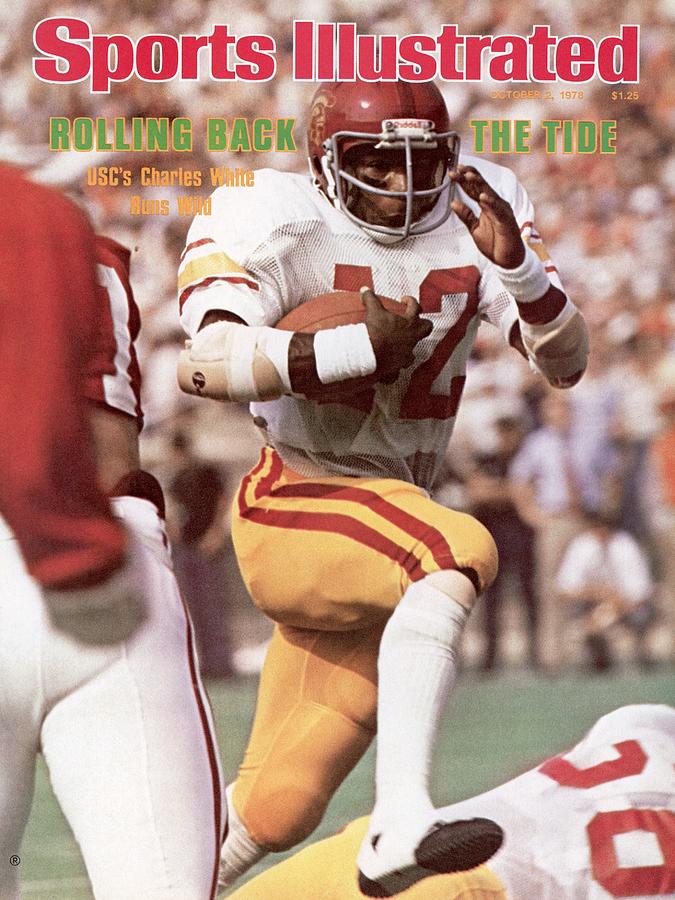

Charles White, USC running back (1976 to 1979):

Best known: The ’79 Heisman Trophy winner, also fourth in the voting in ’78, out of San Fernando High led the nation in rushing both seasons, topping the 2,000-yard mark in 12 games with 19 touchdowns his final year. He was also a two-time Rose Bowl Player of the Game. “He was the toughest player I’ve ever coached — the toughest man I have ever known,” said John Robinson, White’s USC coach who later brought him on to play in the NFL with the Los Angeles Rams (wearing No. 33). Added Rams quarterback Jim Everett after White led the NFL in rushing in 1987: “I’ve never seen a tougher individual than Charles White.” In high school, he ran for 1,118 yards and 14 touchdowns, averaging 9.4 yards a carry and made an immediate impact as a true freshman at USC with 858 yards and 10 touchdowns while backing up Ricky Bell. USC went 42-6-1 during his four years, winning the 1978 national title and four bowl games, three of them in the Rose Bowl. He was inducted into the USC Athletic Hall of Fame in 1995, the College Football Hall of Fame in 1996, and named to the Pac-12 All-Century Team in 2015.

In ESPN’s 2020 list of the 150 greatest college football players in the game’s first 150 years, White is listed at No. 96 noting his 5,598 rushing yards; 6,545 all-purpose yards and 46 touchdowns. He capped his college career with one of the great performances in bowl history, rushing for 247 yards on 39 carries while battling the flu in a dramatic 17-16 victory over Ohio State in the Rose Bowl. His diving touchdown with 1:32 to play was the deciding score on a drive where he accounted for 70 of USC’s 80 yards. White died at age 64 in 2023 after a long battle with dementia and cancer, almost forgotten by the school.

Not well remembered: A California high school state champion in the 330-yard hurdles, White also ran hurdles on USC’s 1979 track team as a senior.

James Harris, Los Angeles Rams quarterback (1974 to 1976):

Best known: Once the quarterback out of Grambling became a Rams’ starter in ’75, Harris made his one and only Pro Bowl. The first African-American to open a season as his team’s starting quarterback in NFL history that season, he injured his shoulder in Week 13, then returned for the NFC title game against Dallas. But after throwing an interception and watching the Rams fall behind 21-0, Harris was substituted out for Ron Jaworski.

Not well remembered: As a backup to John Hadl, Harris wore No. 11 in his first season of ’74 that spanned eight games.

Dusty Baker, Los Angeles Dodgers outfielder (1976 to 1983):

Best known: The Dodgers pried away the Riverside native from Atlanta in 1975 — sending Lee Lacy, Jimmy Wynn, Tom Paciorek and Jerry Royster in exchange. As a Dodger, he went to two All Star games (’81 and ’82), won two Silver Slugger awards and one Gold Glove. His 30th home run on the last day of the 1977 season off Houston’s J.R. Richard put him as part of a group of four Dodgers to accomplish the feat. He was fourth in the NL MVP voting in 1980 (when he hit .294 with 29 homers and 97 RBIs). He hit .320 in the strike-short 1981 season and .300 in ’82. His Dodger career shows three World Series appearances. In addition to his 19 years as a player, he’ll likely end up in the Baseball Hall of Fame for his managerial career — 26 seasons, 2,182 wins, a World Series and three pennants with San Francisco, Chicago, Cincinnati, Washington and Houston.

Not well known: Baker said he wore No. 12 because growing up as a Dodgers fan, his favorite player was …

Tommy Davis, Los Angeles Dodgers outfielder (1959 to 1966), California Angels outfielder (1976):

Best known: The NL batting champion in back-to-back seasons (.346 in 1962 and .326 in 1963) during the first two years of Dodger Stadium’s opening continues to maintain the team’s single-season RBI record with 153 in ’62, as well as the L.A.-franchise record of 230 hits in the same year. The three-time All Star who grew up in Brooklyn had a career. 294 average covering 18 seasons and 10 teams. The year Maury Wills won the ’62 NL MVP Award, Davis was third in the voting.

Davis’ career took a wrong turn on May 1, 1965 when he broke his right ankle on a slide into second base, his spike catching the dirt early as he was going from first to second on a grounder to first. Davis, then 26, later said: “I don’t know how it happened. I thought there was going to be a play on me, and I came in with a new kind of slide. When I looked down, I thought my ankle was in right field.” After eight years with the Dodgers, Davis ended up wearing nine different numbers going through nine more teams, including the Angels in 1976 at age 37 as a DH (.265 in 72 games with three homers and 26 RBI, wearing No. 9).

Not well known: In ’63, after winning his second NL batting title, Davis was eighth in the voting for league MVP. Three teammates were ahead of him: Winner (and unanimous Cy Young winner) Sandy Koufax, reliever Ron Perranoski and second baseman Jim Gilliam.

Dwight Howard, Los Angeles Lakers center (2012-13):

Best known: The seven-time Eastern Conference All Star center came to L.A. in a four-way deal from Orlando as a way to test drive the Laker experience before he became a free agent. Howard made the Western Conference All-Star team, led the league with 12.4 rebounds a game to go with 17.1 points, yet, despite all pleading that included some public billboards, Howard took his so-called talents to Houston.

He did circle back in 2019-20 instead, at age 34, as a backup center wearing No. 39 on a team that won the NBA title in the COVID short-season.

He came back a third time in 2021-22, at age 36, and kept No. 39 again.

For a career that lasted 18 seasons, five first-team All-NBA selections, three times NBA defensive player of the year, and 19,485 points to go with 14,627 rebounds, and 2,228 blocks, Howard became part of the of the 2025 class of the Basketball Hall of Fame.

Also in ’25, Howard wore No. 12 when he joined the L.A. Riot of the Big3, an Ice Cube-endorsed, eight-team 3-on-3 summer league/financial proposition with former NBA players and coaches moving around to various NBA arenas.

Not well known: Howard said he picked No. 12 because he admired Kevin Garnett, who wore No. 21 with Minnesota, so Howard flipped the digits.

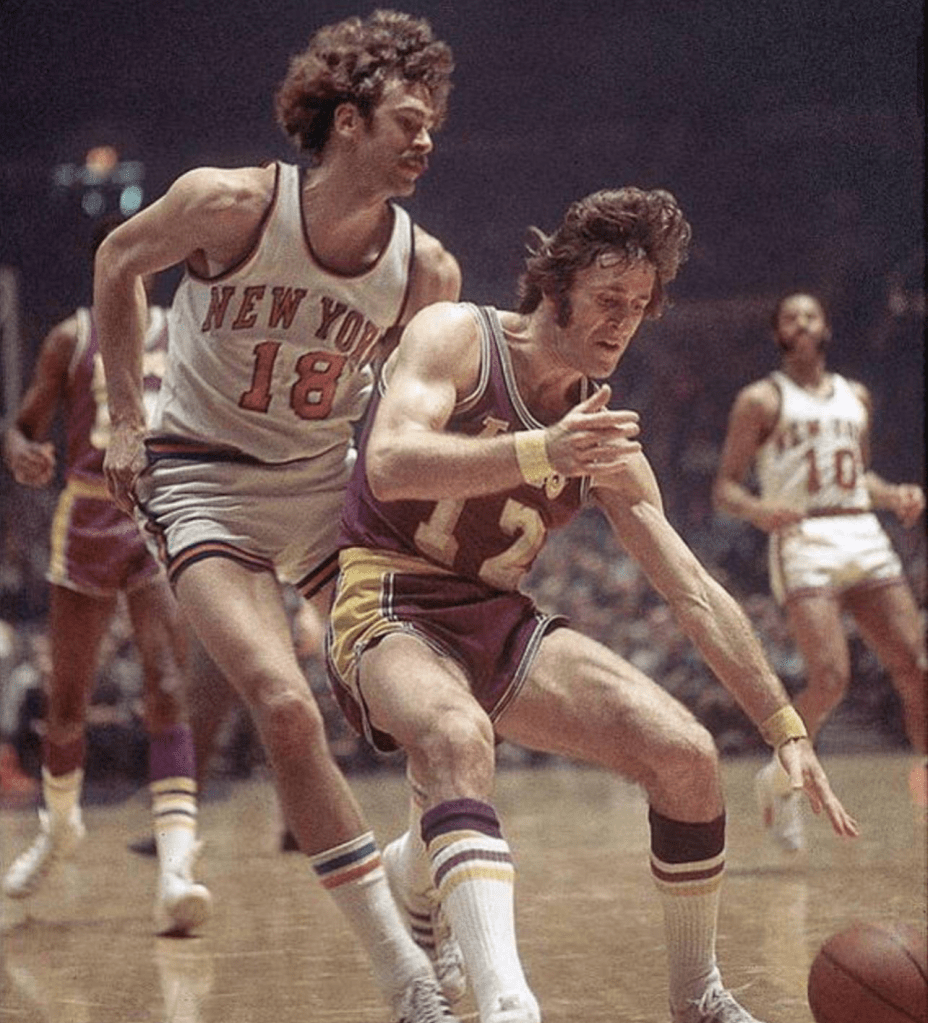

Pat Riley, Los Angeles Lakers guard (1970-71 to 1975-76):

Before he made himself a Basketball Hall of Fame coach with the Lakers, Riley carved 10 years out in the league as a player, including six with the Lakers, one as part of the 1971-72 NBA title team. Only one of those seasons did he average double digits in points per game — 11.0 in ’74-’75, which was his career best. His all-time game was a 38-point effort in a Lakers’ five-point win over the New Orleans Jazz in 1974. Now they have built a statue for him outside the Crypto.com Arena. A place where he never coached.

Gerrit Cole, UCLA pitcher (2009 to 2011):

Added to the UCLA Athletic Hall of Fame in 2022, the Orange Lutheran standout posted a 3.38 ERA and 376 strikeouts over 322 1/3 innings in 50 games during his three years at UCLA. At the conclusion of his junior year, he was selected No. 1 overall in the 2011 MLB Draft by Pittsburgh, becoming the first-ever top pick in program history. A Freshman All-American in 2009 and second-team All-American in 2010, Cole helped the Bruins to back-to-back NCAA Tournament berths in 2010 and 2011, including a trip to the 2010 College World Series. He still ranks second in program history in career strikeouts. Cole has worn No. 45 during his 11-year MLB career with Pittsburgh,Houston and the New York Yankees (where he was the 2023 AL Cy Young winner). The Yankees originally took Cole as the No. 28th pick overall in the 2008 MLB Draft, but he declined and went to UCLA.

Denise Curry, UCLA women’s basketball center (1977-78 to 1980-81):

The Basketball Hall of Fame member was a three-time All-American and four-year starter with the Bruins averaging 24.6 points and 10.1 rebounds a game, setting 14 school records and establishing all-time marks for points and rebounds at the school. A leader on the 1978 AIAW national championship, she was a three-time Western Collegiate Athletic Conference Most Valuable Player, the 1981 UCLA All-University Athlete of the Year and First Team Academic All-America. On the international level, Curry captured gold medals at the 1984 Olympics, the 1983 Pan American Games, and the 1979 World Championships, and also earned silver medals at the 1983 World Championships, the 1981 World University Games, and the 1979 Pan American Games.

Steve Sogge, USC football quarterback (1966 to 1968): At just 5-foot-10 and 170 pounds, Sogge played above his weight at Gardena High as the Los Angeles City Section Player of the Year, leading the Mohicans to a City Section title and passing for what was believed to be a high school record of 2,361 yards as a senior. Selected as a Parade All-American, USA Today rated him in 2021 as one of the 10 greatest quarterbacks in California high school football history. Sogge’s jump to USC for football included starting on the ’67 national championship team as a junior with running back O.J. Simpson and a No. 2 ranking for the Trojans in ’68. Sogge switched from No. 14 in 1966 to No. 6 and No. 12 in 1967 and ’68. Baseball was also his fortay as he played at USC and went straight to the Los Angeles Dodgers’ farm system (1969 and ’70) as a catcher and third baseman.

Trevor Moore, Los Angeles Kings left wing (2019-20 to present): The Thousand Oaks native took No. 12 after wearing No. 42 during his first three seasons in Toronto, traded to L.A. in a deal for Kyle Clifford and Jack Campbell. Moore’s overtime goal for the Kings against Edmonton in Game 3 of the 2023 playoffs clinched his place in team lore.

Amy Rodriguez, USC women’s soccer (2005 to 2008): The Gatorade National Player of the year in 2005 at Santa Margarita High became the Trojans’ fourth all-time leading scorer, scored 12 career game-winning goals and led the team to the NCAA championship. She was also part of two gold-medal U.S. Women’s Olympic teams.

Bill Madlock: Los Angeles Dodgers third baseman (1986 to 1987): The three-time NL All Star and four-time NL batting champion hit .360 after the Dodgers picked him up at the waiver trade deadline in ’85 (where he took on No. 52) and he became one of two Dodgers to ever homer in three straight games in a single postseason (in six games of the NLCS loss vs. St. Louis, where he was 8 for 24). The Dodgers sent away R.J. Reynolds, Cecil Espy and Sid Bream to Pittsburgh for him.

Have you heard this story:

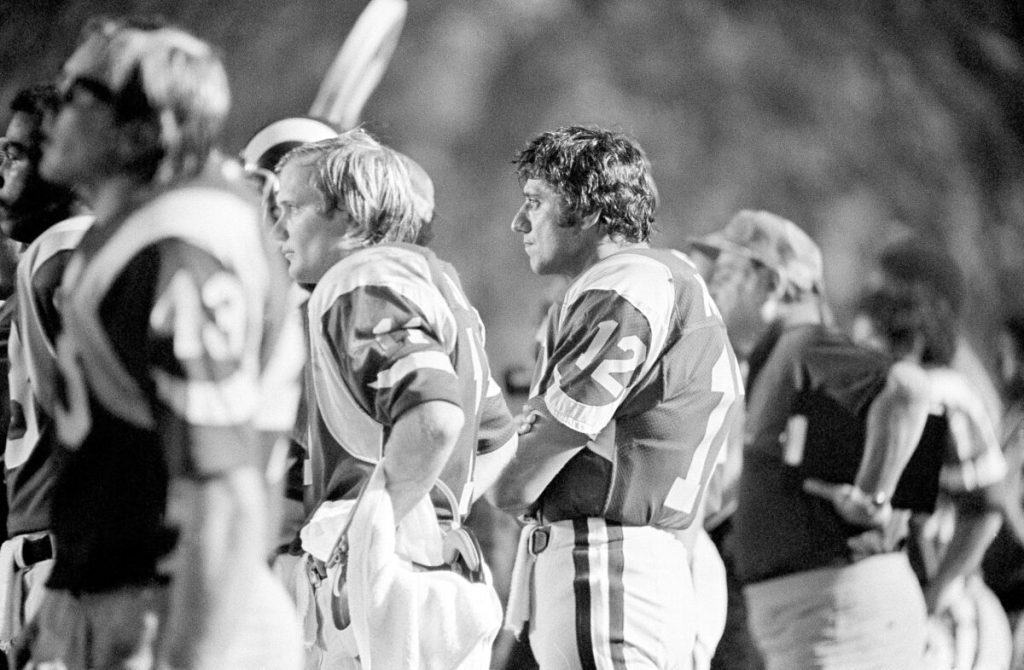

Joe Namath, Los Angeles Rams (1977):

In his autobiography, “All The Way: My Life In Four Quarters,” there’s “Broadway Joe” lamenting his life in Los Angeles, at the end of a 12-year run with the New York Jets, trying to hang on with the Rams. It lasted just four games. In a Week 4 Monday Night Football loss at Chicago, he was knocked out of his 140th and final NFL contest. The last pass Namath ever threw was intercepted by the Bears, though Namath says he never actually saw the interception because “I took a helmet to the chest.” Pat Haden took over, Vince Ferragamo was the new No. 2, and Namath had a glorified sideline pass at the Coliseum. Namath then wrote about his lonely Christmas of 1977 living in Long Beach, followed by the realization he was in Hollywood and could be in some movies. That worked out swell.

A treat: Here’s a Rams-49ers game from 1977 Week 3 — Vin Scully and Sonny Jurgenson on the call for CBS (as Namath was 7-for-14 passing, 126 yards, no TDs in a 34-14 victory):

Randall Cunningham, Santa Barbara High School quarterback (1979 to 1981):

Perhaps once playing in the shadow of older brother and USC star Sam “Bam” Cunningham, Randall led the Dons football team to a school-record 13 victories in 1980 and into the CIF finals before he became a record-setting passer and punter at UNLV (1982 to ’84) and a unique running quarterback in the NFL for 16 seasons. In a 15-14 win over Dos Pueblos at UCSB’s Harder Stadium, Santa Barbara High trailed by seven with less than a minute left at their own 27-yard line. Cunningham was flushed out of the pocket, headed toward the left sideline, then chased to the right sideline and threw a 50-yard pass to tight end Fred Adam. After scoring a touchdown to cut the deficit to one, the Dons went for two — Cunningham rolled out and dove into the end zone for the win. Santa Barbara lost to Long Beach Poly in the CIF final. His SBHS No. 12 was retired by the school in 2010 — the number Cunningham also wore at UNLV and during his 11 seasons with the Philadelphia Eagles, then retired in 1996, then came back to play five more seasons through age 38 and amass 4,928 yards rushing with 35 touchdowns, versus nearly 30,000 yards passing for 207 touchdowns. He is also a 2016 inductee into the College Football Hall of Fame and UNLV retired his No. 12.

Rod Sherman, USC football receiver (1964 to 1966):

The claim to fame for the Muir High of Pasadena standout was pulling in a Craig Fertig fourth-down pass for a 15-yard touchdown with 1:33 to play to knock off unbeaten Notre Dame, 20-17, capping a comeback from 17 points down. The famous call — 84-Z Delay — was what Sherman suggested to coach John McKay, who then sent Sherman into the game. Sherman captained the 1966 Trojan team that played in the Rose Bowl, and earned All-Conference first team honors that season. In his USC career, he caught 90 passes. He capped his seven-year NFL career with the Los Angeles Rams (wearing No. 86). He was inducted into the USC Athletic Hall of Fame in 2018.

Erik Kramer, Burroughs High (1981) and Pierce College (1984) quarterback:

Born in Encino, and a defensive back in high school who didn’t play quarterback into his third year out of high school, Kramer would end up at North Carolina State (1985 to ’86) as the conference player of the year. Undrafted, he emerged as a starting quarterback with the NFL’s Detroit Lions and Chicago Bears after a stint in the Canadian Football League. In 2011, Kramer’s 18-year-old son, Griffen, a senior at Thousand Oaks High School, was found dead at a friend’s home from a heroin overdose. Kramer attempted suicide four years later with a gunshot to the head, but survived it. Living in Agoura Hills, Kramer, who has his own website ErikKramer12.com, wrote a book, “The Ultimate Comeback” about his life in 2023.

Jeff Kent, Los Angeles Dodgers second baseman (2005 to 2008):

Bellflower-born and a Huntington Beach native out of Edison High, Kent spent the last four of his 17-year career as a Dodger, trying, as a 40-year-old curmudgeon sage, to mentor to a group of young stars coming up. This was many seasons after Kent had been a Dodger nemesis with the rival San Francisco Giants. He made the 2005 All Star team as a Dodger and won a Silver Slugger Award as well. He also hit the last 75 of his 377 homers as a Dodger. Because 351 of that total came in games where he was playing second baseman, that was enough to get him inducted through the back door into the National Baseball Hall of Fame through a vote of the veterans’ committee. In a dozen decades, we’d never have guessed that outcome for someone who, while playing for six MLB teams, wasn’t even the best (or well-liked) player on any of them.

We also have:

Juju Watkins, USC women’s basketball guard (2023-24 to present): Leading a renaissance of women’s college basketball? That’s what it says here. It’s a story in progress.

Pete Beathard, USC football quarterback (1961 to 1963); Los Angeles Rams quarterback (1972)

Mark Langston, California Angels/Anaheim Angels pitcher (1990 to 1997)

Les Horvath, Los Angeles Rams running back (1947 to 1948)

Zeke Bratkowski, Los Angeles Rams quarterback (1961 to 1963)

Toby Bailey, UCLA basketball guard (1994-95 to 1997-98)

Willie Randolph, Los Angeles Dodgers second baseman (1989 to 1990)

Jim Tracy, Los Angeles Dodgers manager (2001 to 2005), wearing No. 16 for ’04 and ’05

Brad Ausmus, Los Angeles Angels manager (2019)

Steve Finley, Los Angeles Dodgers outfielder (2004); Los Angeles Angels outfielder (2005)

Anyone else worth nominating?

1 thought on “No. 12: Richard Nixon”