This is the latest post for an ongoing media project — SoCal Sports History 101: The Prime Numbers from 00 to 99 that Uniformly, Uniquely and Unapologetically Reveal The Narrative of Our Region’s Athletic Heritage. Pick a number and highlight an athlete — person, place or thing — most obviously connected to it by fame and fortune, someone who isn’t so obvious, and then take a deeper dive into the most interesting story tied to it. It’s a combination of star power, achievement, longevity, notoriety, and, above all, what makes that athlete so Southern California. Quirkiness and notoriety factor in. And it should open itself to more discussion and debate — which is what sports is best at doing.

The most obvious choices for No. 8:

= Kobe Bryant: Los Angeles Lakers

= Troy Aikman: UCLA football

= Steve Young: Los Angeles Express

= Drew Doughty: Los Angeles Kings

= Reggie Smith: Los Angeles Dodgers

The not-so-obvious choices for No. 8:

= John Roseboro: Los Angeles Dodgers

= Tommy Maddox: Los Angeles Xtreme

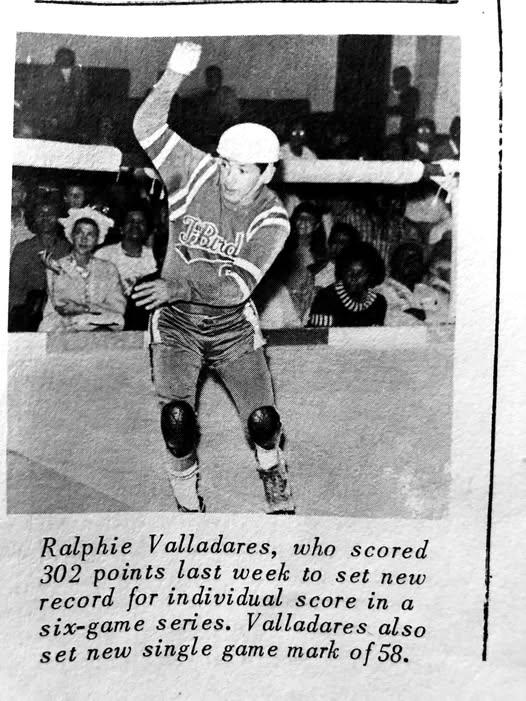

= Ralphie Valladares: Los Angeles Thunderbirds

= Teemu Selanne: Mighty Ducks of Anaheim

The most interesting story for No. 8:

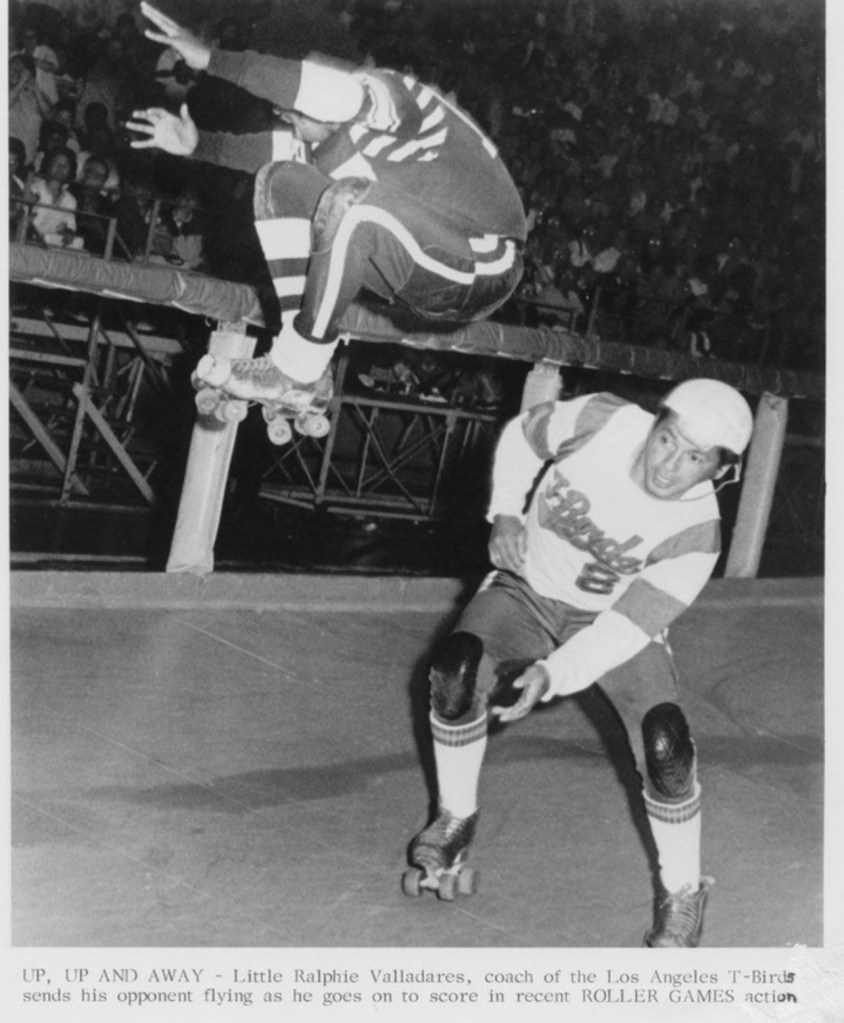

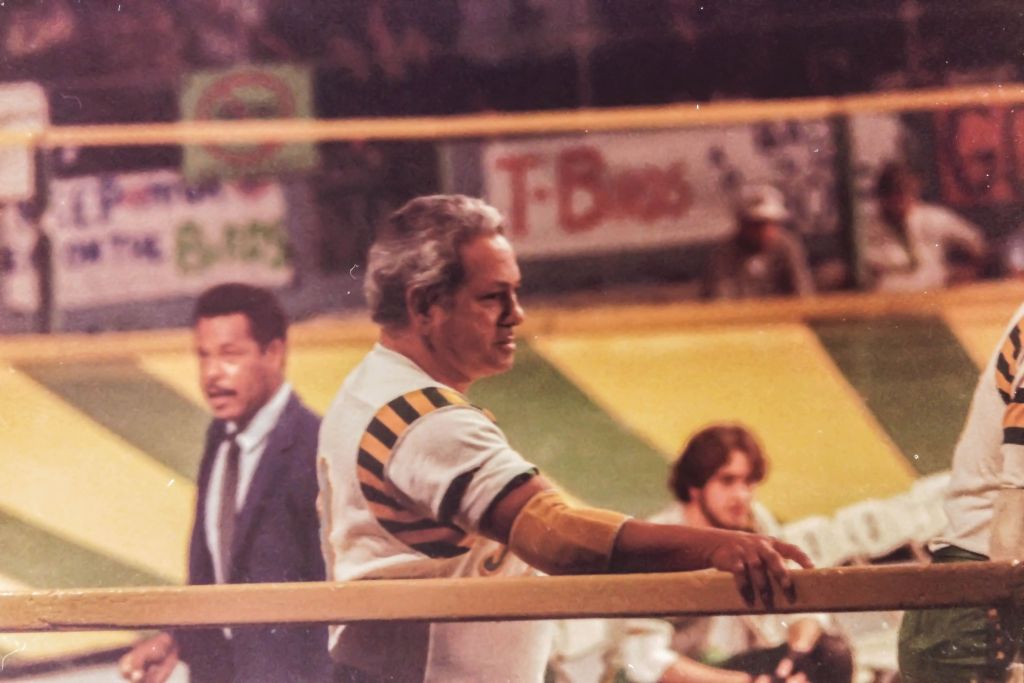

Ralphie Valladares, Los Angeles Braves (1953 to 1959); Los Angeles Thunderbirds (1961 to 1993)

Southern California map pinpoints:

Inglewood, Pico Rivera, Los Angeles (Olympic Auditorium)

In what was a real-deal world of Roller Derby, Ralphie Valladares brought validation, valor and viscosity for those pulling for the underdog. Even a trace of Prince Valiant.

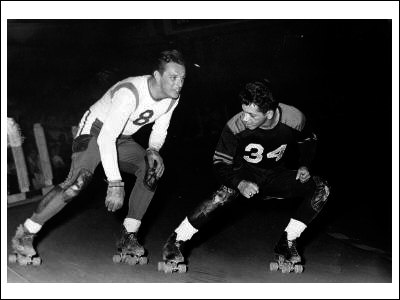

No. 8 wasn’t just gritty great, he could flat-out skate. A lightning-fast play maker for the red, white and blue Los Angeles Thunderbirds, our own very diverse and equally dynamic team of men and women. An abject reflection our city’s inclusive melting pot and blue-color mentality.

It was not a stretch to look back on Valladares as the first high-profile relatable Latino sports star in Los Angeles, some 20 years before Fernando Valenzuela and his mania turned up in the 1980s. At which point in time Valladares was still around to see what kind of magic his sport could squeeze out for this generation at the height of the roller disco scene.

You couldn’t help but buy into the showmanship, and pop culture value, much like an audience would with the Harlem Globetrotters or the Savannah Bananas. There was art, merit and an authentic skill set necessary.

Even kids figured that out if they tried to replicate it on the playground wearing those plastic Dodger give-away batting helmets and hand-me-down four-wheeled skates an older sister might have once worn as a dream to be a figure skater on asphalt, it took talent or else you’d be just another skid mark.

We figured out this was a bit like Three Stooges rough-house theater, cartoons come to life. The merriment of a merry-go-round full of arm whips, flying elbows and heavy pouncing, wrapped up by the theatrics of an obnoxious infield interview and folding-chair throwing, turning over tables in faux anger, was an outlet.

This thing we were captivated by on TV — and at some point, we might have had to adjust tin-foil wrapped TV antennas on the black-and-white Zenith to find the UHF station actually delivering the Sunday night video taped action between 7 and 9 p.m. — also had a scoreboard. A rudimentary graphic popped up full screen to show that what we saw was as important as an MLB or college football game.

Someone was keeping track. We counted on that, too.

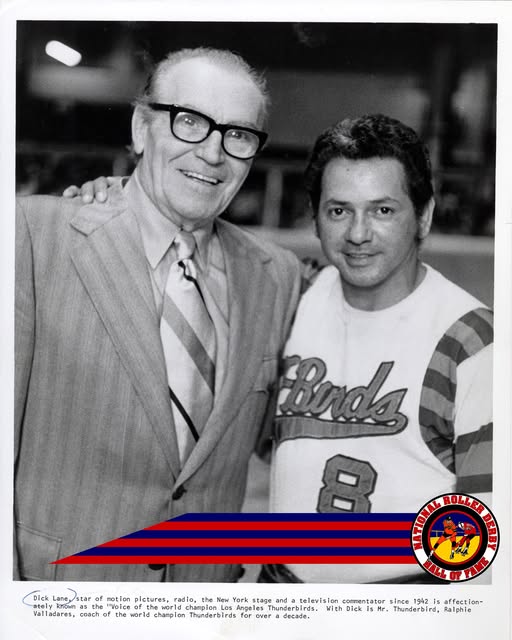

For some 50 years, Valladares played the part of player, coach and manager, spanning the 1950s to the early ’90s as the sport kept changing names and venues, something like a medicine show with Dick Lane as the Professor Harold Hill character, barking out the Richmond-9-5171 phone number to lure anyone into the otherwise sketchy Olympic Auditorium in downtrodden downtown L.A.

Lane was also the one screeching all too often: “There goes Little Ralphie Valllladarrezzzzzz on the jam!!”

That was our jam.

And while we all bought in on the statement that Valladares was the sport’s all-time leader in whatever made-up but important numbers they had created — matches played, career points, points scored in a single game, or bruises distributed — the ageless wheelman was all there for its seemingly entire sweet spot of history.

Scott Stephens, a longtime fan, one-time Roller Games skater and author of the 2019 “Rolling Thunder: The Golden Age of Roller Derby & The Rise And Fall of the L.A. T-Birds,” honestly wrote in his book: “Ralphie Valladares was the first and last T-Bird star.”

Yet none of this might have happened if Valladares had his athletic career go the way he thought it was heading. He dreamed of becoming a championship jockey riding thoroughbreds near his home at another famous oval, Hollywood Park. But something rolled him into a much different arena.

Roller Derby, as it was generally called when it launched in the 1930s in Chicago, had evolved from a cross between marathon dancing and endurance roller skating in its early form.

It began to take on a nuanced sports vibe when famed sportswriter Damon Runyon, after watching a match in Miami, suggested to its organizers if might try breaking up into teams of five men and women on a side, with points scored as opponents were lapped. He also thought there should be more contact and less dancing. The hits could even be a bit exaggerated a bit.

The first TV sets arriving in New York were the test cased for showing Roller Derby matches in the 1940s, much like boxing and wrestling fit into the screen best. When the governing body’s business operations moved to Northern California in the late 1950s, the TV aspect was found to be of even more valuable. It was a big-market, not-so-niche sports what had no offseason and could draw fans as many nights as it wanted.

Some promoters had visions of this becoming a legit Olympic sport. It was entering pop-culture status.

When the decade of the 1960s rolled around, a rival Roller Games/National Skating Derby emerged, and the Los Angeles Thunderbirds were its anchor team. Hollywood producer/promoter Bill Griffiths and his partner Jay Hall saw an opportunity.

In Los Angeles, the Roller Derby had a base with a team called the Braves. At the end of the ’50s, the Braves were displaced from the local market for a couple of years, moving to Northern California as the foil for its burgeoning base of San Francisco Bay Bomber fans.

Griffiths and Hall knew there was enough SoCal talent to support a new team.

Ralphie Valladares was part of that plan.

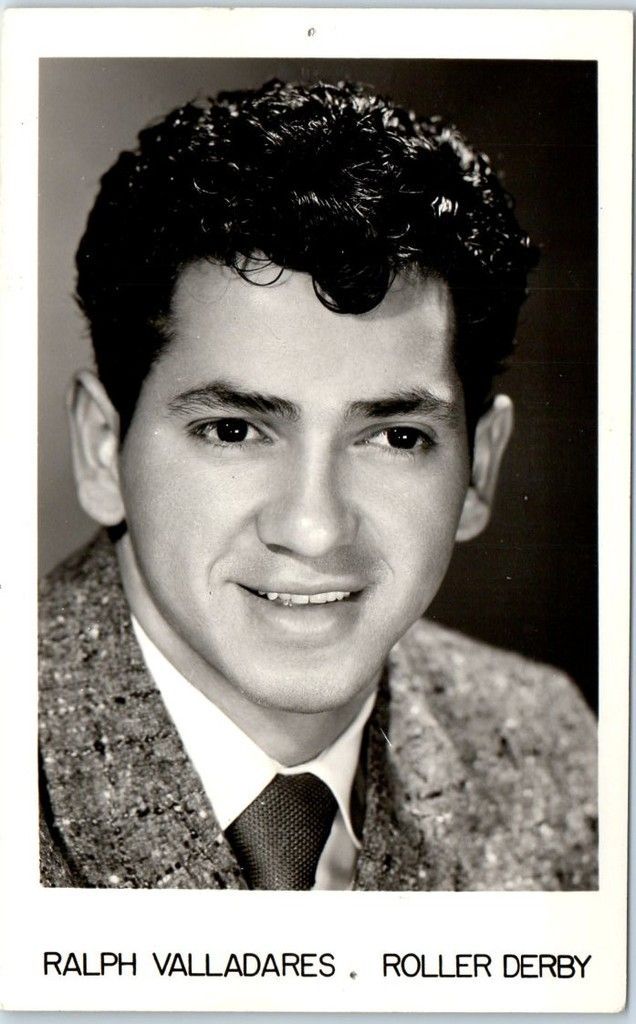

Ralph Dwight Valladares was born July 31, 1936 in Guatemala City, Guatemala, and his family moved to the United States when he was 12. Growing up near Hollywood Park in Inglewood, he was lured into the place and roamed the stables, eventually becoming an exercise rider.

But as he started growing — up to 5-foot-2 and 115 pounds by age 16 — he seemed to be too big for a jockey but too small for most other sports. The local roller rinks got his attention, he was a champion flat-track skater, setting local speed titles, a human version of the thoroughbreds.

With more the looks of contemporary actor Sal Mineo, Valladares drew the attention of a professional tryout with the Roller Derby, quit high school his junior year, and signed a contract at 17 in 1953.

Eventually assigned to the Los Angeles Braves in 1956, Valladares was immediately, and intimately, one of the sport’s fan favorites, added to the Roller Derby All Star teams that year as well as in ’57 with the team.

Transferred to other teams playing in the San Francisco for a couple of years, Valladares soon became valuable in the Roller Derby international expansion, making overseas tours.

When the new Roller Games were created as a rival league to Roller Derby, with L.A. back as the home base, Valladares returned to start a long association with the Thunderbirds as well as continue to be an international ambassador. In that time, Valladares helped organize the Australian T-Birds and also coached and competed with the Tokyo Bombers and Latin Liberators while also keeping tabs in and out with his L.A. team.

In 1950s, ’60s and ’70s, as the car culture took over Southern California, these aptly named T-Birds were kings of the sports landscape against the newly planted Dodgers and Angels, as well as the established football programs at USC and UCLA that focused more on congealing with the NFL’s Rams. The T-Birds were just as popular, if not more, with the citizenship that had constant TV access versus limited, seasonal play by the other sports somewhat afraid to give it away on the burgeoning medium.

For infield manager Red Smatt, Valladares was the iconic “Guatemalan Flyer,” often teaming up with Ronnie “Psycho” Rains and other colorful nicknamed teammates on powerjams, skating rings around the propped-up opponents. Also very much part of it was his on-again, off-again wife, fellow legendary T-Birds skater Gloria “Honey” Sanchez.

Whether or not you watched in person, or most likely tracked it down onr KTLA-Channel 5, KHJ-Channel 9 or KCOP-Channel 13 — maybe even resorting to remote VHS KBSC-Channel 52 on the other dial coming out of distant Corona — there had to that moment when you wondered how the whole thing might be scripted. How the violent hits were not full-on injury inducing because the players came back week after week. Mostly.

Somehow, Valladares only suffered one major injury in his whole career — a broken collarbone. Few could keep up and collar him when he was on a roll.

And he was there year after year.

Even as the team changed to a green-and-gold yellow scheme in the late ’70s, Valladares could be spotted going into his crouch, weaving through the pack, keeping his balance and, if need be, springing up to catapult an opponent over the railing and into someone’s dinner of popcorn and beer. Valladares then dared come full circle to punctuate the move as the other guy was trying to crawl back into the ring, sending him back flying past a TV cameraman.

In an environment created for clear-cut heroes and villains — the white shirts against the red shirts provided the visual cues — Valladares did what was necessary to champion the undersized skater up against towering opposition.

Eventually, Valladares saw the need to be more invested in training the next generation of skaters, starting a school at the T-Bird Rollerdrome in Pico Rivera with teammates John Hall and Debbie Heldon, something that stayed around until the mid 1980s. Valladares was into upper management, helping the business pivot, or punt, when necessary.

In his 2014 book “Roller Derby Requiem,” Las Vegas-based writer Ed Koch explained how Valladares didn’t mind if reporters ever asked him about the legitimacy of roller derby.

“There are many sports you can argue that are phony,” he once said. “At one time or another, hockey, baseball, boxing and horse racing have been accused of being fixed.”

It was the showmanship that Valladares appreciated the most. And he could pull it off.

Koch better explained as well the numbering system Roller Derby teams had over the years. The Los Angeles Thunderbirds, for example, had a team that always wore numbers 1 through 10, both the men and women. Rival teams took numbers 11 to 19, 20 to 29, up through the 60s.

The exception was how No. 1 was symbolically taken out of circulation in respect for those who died in a 1937 a bus crash in Salem, Illinois. Some 21 skaters and officials traveling for a Roller Derby game died, just two years after the league was created. When Roller Games came in the 1960s, it didn’t immediately follow that protocol, and Valladares wore No. 1 until he was informed about that tradition and switched to No. 8.

So, how good was Valladares?

Koch dedicated a chapter in his book to him and took a slice from 1985, when Valladares was 44 years old, helping the ESPN video crew capture action during the women’s event and strapped a small portable camera on Valladares’ right shoulder. As the women’s pack skated around the track, Valladares skated backward and stayed ahead of the pack, capturing the action was the jammers skated past him.

“You knew if he wanted to, Ralphie could have kept pace with them and lapped the pack along with the jammers,” wrote Koch. “Instead he kept the camera squarely on the pack … it gave the post-production a camera angle they had never seen before or sense. …

“That’s how great a skater Valladares was. I first saw him on TV in the early 1960s and I swear the man never lost a step as the years went by.”

The first year of the L.A. T-Birds’ Roller Games in 1961 happened at the 2,500-seat El Monte Legion Stadium before moving to the famed Olympic Auditorium, where some 9,000 loyal every week could easily end up as part of the TV background when a player or chair fell near them.

The T-Birds, who also trained at the Valley Gardens Arena in North Hollywood, found skating matches in Southern California at venues such as at the L.A. Sports Arena, the Inglewood Forum, Long Beach’s Veterans Stadium and the Convention Center, the Anaheim Convention Center, San Bernardino Showgrounds and Swing Auditorium, the Ventura Fairgrounds, the Earl Warren Showgrounds in Santa Barbara, the Hollywood Palace and the Santa Monica Civic Auditorium — with an occasional trip to the San Diego Sports Arena.

Eventually, by mid-September 1972, they took over a Major League Baseball diamond, setting up a track near second base at Comiskey Park in Chicago before more than 50,000 fans. Even if most were too far from the action.

This is what most accept as the sports’ high mark, with a newly-released film,“Kansas City Bomber” starring the bombshell Raquel Welch giving roller derby a beautiful makeover. It not only featured Valladares and his T-Bird teammates as part of the game-action sequences, but Dick Lane played himself with his famous “Whoa Nellie!” screams to make it all seem more authentic as it was filmed in Portland, Oregon.

At the same time, a Roger Corman-produced film, “The Unholy Rollers” came out with former Playboy Playmate Claudia Jennings in the starring role.

A year later, Jim Croce came out with his song, “Roller Derby Queen.”

The night that I fell in love with a Roller Derby Queen / (Round ‘n’ round, oh round ‘n’ round) /

The meanest hunk o’ woman that anybody ever seen / Down in the arena

Valladares, familiar with his own Roller Derby Queen, would manage to spend some 38 years with the T-Birds organization, amassing annual “world title” trophies for the team’s collection. Part of his job was also as part of the crew who helped set up and take down tracks in venues for road games to insure safety,

The last time he participated with the T-Birds was before 10,000 in Auburn Hills, Michigan, in 1993. One of the members of the T-Birds on that night was his daughter, Gina.

Roller Games lasted until the mid-70s, and featured beloved participants T-Birds participants such as Big John Hall, Danny Reilly, Terri Lynch, Shirley Hardman, plus Earlene “747” Brown next to Gwen “Skinny Minne” Miller. Also, George Copeland, the first Black skater in league history. Valladares and Hall were able to bring the league back again after 1975, investing their own resources, and iterations of it lasted until the 1980s and ’90s when ESPN tried to make it part of its early-existence programming with Australian Rules Football.

In 1988, Valladares was quoted in the (Utah) Park City Record, promoting an event there, that he always encouraged showmanship in the sport.

“I can teach anybody to skate, but I can’t teach people how to get along with other people. They either have it or they don’t.

“Most people in sports have a bit of ham in them whether we’re talking baseball, football or hockey. Roller derby is no different. What we do is entertain people, I hope. I think people leave with a good feeling.”

In 1990, as pro wrestling was having a moment, something called the Rock ‘N Roller Games came up as a syndicated TV program, and Valladares was there with his T-Birds. This time, catering to a new generation of viewers, the banked oval was replaced by a Figure 8 track. There was a “Wall of Death” incorporated as well as a 60-degree turn near a live alligator pit. Rock bands played along with the action. It lasted just a short time. Thankfully.

St. Louis writer Jeff Gordon noted: “There is a new breed of foes for 900-year-old Ralphie Valladares and his intrepid T-Birds: The Rockers, the Bad Attitudes, the Violators, the Maniacs and the Hollywood Hot Flash. … Maybe (Ronnie ‘Psycho’) Rains will come out of retirement and toss nemesis Ralphie Valladares into the Live Alligator Pit! Is this a great country or what?”

In retrospect, the Olympic Auditorium, built in 1925 and used for boxing in the 1932 Olympics, was as much a star for the sport as some of the players. It provided the rather seedy ambiance for a place that had not really seen better days — it was a palace for decades of brutal boxing matches and fans throwing beers into the ring if led to disappointment. Much of that is chronicled in the brilliant documentary “18th and Grand” by Steve DeBro.

In 2009, successful Hollywood TV scriptwriter Ken Levine posted on his blogspot about how a new Roller Derby-themed movie was coming out — “Whip It,” directed by Drew Barrymore and starring Ellen Page as an Austin, Tex., misfit who took to the sport. It stirred his memories of growing up watching the sport in Los Angeles.

“We all had our favorite T-Birds — mine were Ralphie Valladeres, John Hall, and Danny Reilly. One of the players wore glasses (Reilly) and I found that hysterical considering players were getting whacked in the chops during the National Anthem.

“I only attended one game in person. Several of my friends and I ventured to the Olympic one night to see the big grudge match between our beloved Thunderbirds and the dreaded Detroit Devils (who could have been the Texas Outlaws the week before, who knew?). The place was packed. You were very close to the action. And the acoustics were LOUD.

“Three memories stand out. The T-Birds won (guess I caught ‘em on a good night), there was an old lady next to me (had to be 90) who stood on her chair and screamed obscenities. And then this – the greatest announcement I’ve ever heard at a sporting event: The P.A. announcer said: “Fans, do not throw anything onto the rink. You have no guarantee it’ll hit the player you’re aiming at.”

After a long bout with diabetes, Valladares died of liver cancer in November of 1998 at age 62 in Pico Rivera and was buried in nearby Rose Hills.

During his final years, Valladares had still been spending a lot of time with Sanchez, whom he had married and divorced three times. The Orange County Register noted that their romance remained strong through marriages and divorces — every time they were married, it happened on St. Patrick’s Day, March 17.

In late ’98, son-in-law Dave Martinez joked with Valladares, wondering if the family should set aside the upcoming March 17 again for him and Sanchez to reunite with another ring ceremony.

Valladares responded: “I’m losing my liver, Dave, not my mind.”

Inducted into the Palm Springs-based National Roller Derby Hall of Fame in 2024, Valladares was “one of the toughest, hardest hitting, most legit skaters to ever grace a banked track,” wrote Stephens, who also created the repository/tribute website LATbirds.net and maintained the fan Facebook page. “He was tough as nails but had a profoundly kind heart … More importantly, he was the team’s highly respected spiritual leader.”

In a city of celebrities, Valladares was one himself and drew some of them to brave the Olympic Auditorium experience to see him perform. Koch noted in his book that among those who came to see him was singer Jose Feliciano. Who happened to be blind.

“During the games, Felicano would have friends describe Valladares’ jams and other game action to him,” wrote Koch. “Even a blind man knew how good a skater Ralphie V was.”

Who else wore N0. 8 in SoCal sports history?

Make a case for:

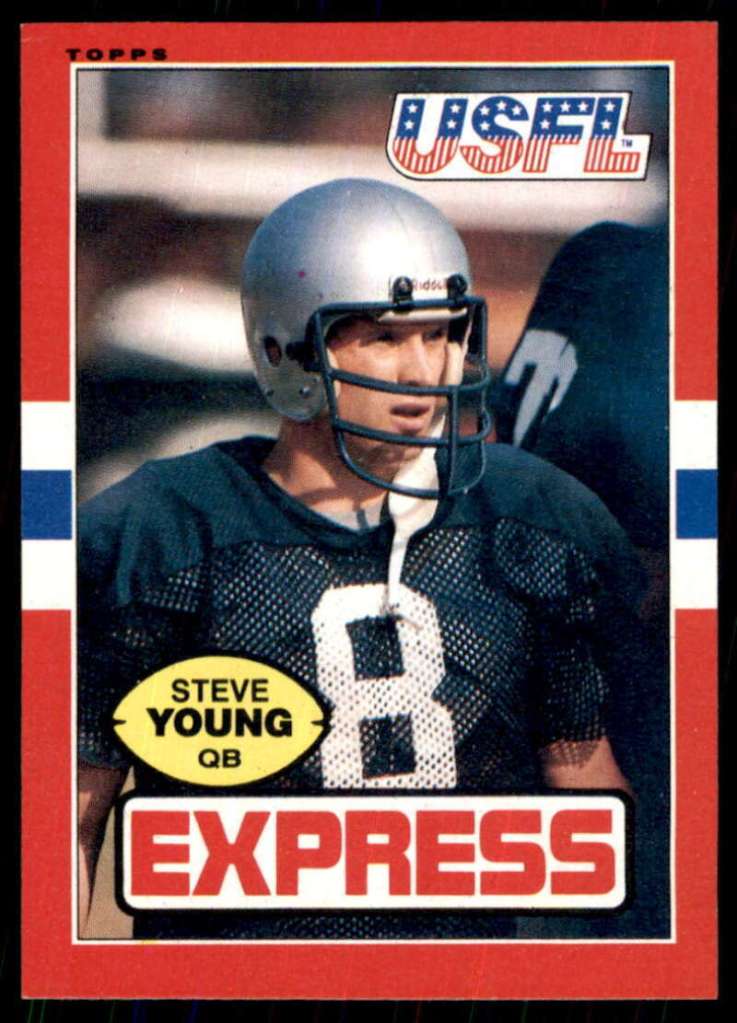

Steve Young, Los Angeles Express quarterback (1984 to 1985):

Best known: Steve Young scrambled his way into the Pro Football Hall of Fame in 2005 after a 15-year NFL career, but only after Los Angeles put him in the express lane.

Coming out of BYU, Young was quickly branded as the United States Football League’s $40 million renegade quarterback — he signed a 10-year deal that was set pay him that much over 43 years in an annuity. But in two spring seasons for the Express, lasting 25 games, he completed 316 out of 560 passes for more than 4,000 yards and 16 touchdowns (against 22 picks). He also piled up 883 yards rushing on 135 carries (6.5 per rush) and nine touchdowns. Included in the later was the game when the team ran out of players and he had to move to fullback in one of the final games of the Express’ existence.

Then there was the time he took up a collection from the players as the bus driver taking them to a home game out in the San Fernando Valley wouldn’t proceed unless he was paid up front. Young may have got about $5 million of that contract he eventually bought his way out of when the league folded.

Not well remembered: Young’s bio on the official Pro Football Hall of Fame site says he came to the NFL “after spending two seasons in the ill-fated United States Football League,” so just know that’s not entirely inaccurate, and there’s more to find out in the 2019 Jeff Pearlman book, “Football For A Buck.”

Troy Aikman, UCLA football quarterback (1987 to 1988):

Best known: A transfer from Oklahoma, Aikman’s two seasons at UCLA were as a starter on a pair of 10-2 teams, establishing school records with 24 touchdowns as a senior and a game with 32 completions, posting a 149.7 passer rating that was among the best in NCAA history. Aikman was a consensus All-American in ’88, winning the Davey O’Brien Award as the nation’s top quarterback and placing third in the Heisman Trophy balloting. That led to Aikman as the No. 1 overall choice in the 1989 NFL draft by Dallas, leading the Cowboys to three Super Bowls over a four-year span and into the Pro Football Hall of Fame. UCLA added him to its Athletics Hall of Fame in 1999, and 10 years later, he finished up two classes to earn a UCLA degree in sociology in 2009

Not well remembered: Aikman was born in West Covina and grew up in Cerritos with a view of Knotts Berry Farm from his house.

Not well known: His No. 8 was retired by UCLA in 2014, but Aikman says the number means nothing to him. He said he grew up wearing No. 10, got to Oklahoma, and when an upperclassmen had that number, he grabbed No. 18. In the 2006 The Sporting News’ “Who Wore What With Distinction: Best by Number,” Aikman continues: “There was no rhyme or reason for (18). And then I transferred to UCLA, I wanted 10 (again) and couldn’t get it, so I said, ‘All right, I’ll be 13.’ Dan Marino was my favorite quarterback. And 13 was retired (for Kenny Washington). I just said, ‘What’s available?’ I picked 8. I liked the single digit so I thought it as kind of cool. And that’s that.”

Also in the book, Aikman said he doesn’t understand why so many become attached to a certain number. “I have companies that send me golf bags and want to put 8 on it. Or you ask the phone company for a number, they want to put 8s in it. And they think that 8 is how you’re identified. I get turned off by that. I don’t want an 8. My name is Troy. I don’t need an 8 on every single thing I own. I’m not identified by the number 8.”

However … Aikman bought a trademark for No. 8 to use in his business activities. Baltimore Ravens quarterback Lamar Jackson challenged Aikman’s use their shared No. 8 in a U.S. Patent and Trademark Office complaint, according to federal records. But in August of 2025, Jackson withdrew the complaint.

Drew Doughty, Los Angeles Kings defenseman (2008-09 to present):

Best known: A perennial Norris Trophy candidate — he did actually win it 2015-16 — the five-time All Star and two-time Stanley Cup champion will have his No. 8 retired some day. On Nov. 8, 2025, Doughty broke the Kings’ record for goals by a defenseman, passing Rob Blake with his 162nd goal in 1,221 games with an empty-netter with 54 seconds remaining.

Not well known: Look up the word doughty in Merriam-Webster and you’ll find a adjective with an old-fashioned flair used to describe someone who is brave, strong and determined. Doughtiness, likewise, is a noun for something that has the quality of being hardy and resolute.

Teemu Selänne, Mighty Ducks of Anaheim right wing (1995-96 to 2000-o1 and 2005-06), Anaheim Mighty Ducks (2006-07 to 2013-14):

Best known: The Finnish Flash spent 15 of his 21 NHL seasons in Anaheim, including a hoist of the 2007 Stanley Cup. Selänne had been leading the Winnipeg Jets with 72 points when he was unceremoniously shipped off to Anaheim in February of ’96 for two first-round draft picks and a third-round pick in the 1996 draft. Paired with Paul Karyia, Selänne scored 36 points in 28 games with the Ducks, and the Ducks made their first playoff appearance in 1997. He was the Mighty Ducks’ leading scorer with 59 points through 61 games in 2000-01 but, with the team in last place, he was traded to San Jose. After the NHL strike in 2005-06, Selänne returned to Anaheim with a one-year, $1 million contract, had 40 goals and 90 points, both leading the team, and he won the league’s Masterson Trophy for dedication and perseverance. After reaching the Western Conference Final in 2006, the renamed Anaheim Ducks brought Selänne back with again with one-year, $3.75 million contract and, leading the team with 48 goals and 94 points, he played in his 10th All Star game. The 2007 Stanley Cup Final was a first for Selänne, who had 15 points in 21 games and won the championship in five games over Ottawa.

Not well remembered: When Selänne returned to Anaheimin 200506, his previously-worn No. 8 had been taken by defenseman Sandis Ozolins, so Selänne put on No. 13, which he had during his first two NHL seasons with Winnipeg.

Reggie Smith, Los Angeles Dodgers outfielder (1976 to 1981):

Best remembered: The Centennial High of Compton switch-hitting standout came to L.A. after All-Star seasons with Boston and St. Louis. “I tell people I was a Dodger before I actually joined the team,” Smith has said. “Being a young, African American player, I had such respect for Jackie Robinson while growing up. When the Dodgers came to Los Angeles, we had the opportunity to see them play. Unfortunately, we didn’t get to see Jackie play because he had retired. He was my boyhood hero, so when I became a Dodger, it was very special.” With the Dodgers, Smith played in three more All Star Games, was fourth in the NL MVP voting in ’77 and ’78 when they won back-to-back pennants, and was still around as part of the 1981 World Series title squad, playing injured but still going 2 for 4 with a sacrifice fly and two RBI as a pinch hitter in the postseason. In 1977, Smith led the NL with a .427 on base percentage to go with a career-high 32 homers, 87 RBIs, 104 runs and a .307 batting average. He followed that up with a season of 29 homers, 93 RBIs and a .295 average with a league-high 13 sac flies. The Dodgers announced he would be added to their “Legends of Dodgers Baseball” group in 2026, citing the fact that among all the MLB switch-hitters, Smith ranks ninth all-time with 314 home runs. And among MLB players not in the Baseball Hall of Fame, he ranks 20th all-time with 64.6 wins above replacement.

Not well remembered: Smith also wore No. 16 when he arrived in L.A. in 1976, and also from 1994 to 1998 when he was a coach.

John Roseboro, Los Angeles Dodgers catcher (1958 to 1967):

Best known: Roseboro made five NL All-Star teams (four in a row during the ’61 and ’62 double dips) as the well-trusted receiver of the Dodgers’ pitching staff. Also wore No. 44 in ’59 and ’60. Roseboro and Don Drysdale appeared together in 283 games, fifth all-time in MLB history for a battery, going back to a season in Brooklyn and 10 more in L.A. For that matter, Roseboro also started 208 games with Sandy Koufax on the mound — including the infamous one in San Francisco when Juan Marichal wasn’t happy with his pitch calling. See more in the Marichal post for No. 46.

Amon-Ra St. Brown, USC receiver (2018 to 2020): Born in Anaheim Hills and a five-star recruit as a senior at Mater Dei High (72 receptions for 1,320 yards and 20 TDs), his breakout season for the Trojans was as a sophomore 2019 with 1,042 yards receiving (13.5 average). A fourth-round pick by Detroit after his junior year, St. Brown became first-team All-Pro in the NFL in 2023.

Jared Verse, Los Angeles Rams edge rusher (2024 to present): The NFL’s defensive rookie of the year award went to the 6-foot-4, 260-pounder out of Florida State, who the Rams took with the No. 19 overall pick in the 2024 draft. The only Rams player voted to the ’24 Pro Bowl had 4 1/2 sacks, 18 quarterback hits and 66 tackles (11 for losses) as a disruptive pass rusher during the regular season, a 57-yard fumble return for a touchdown in an NFC wildcard win over Minnesota and two sacks in the NFC semifinal loss to Philadelphia.

Vince Evans, USC football quarterback (1974 to 1976): The 1977 Rose Bowl MVP threw for more than 1,400 yards and 10 TDs in his senior season, put in charge by coach John Robinson after the departure of John McKay, and won the USC Davis-Teschke Award as the team’s most inspirational player at a time when Black quarterbacks were still seen as something of a rarity. After coming out from North Carolina to spend a year playing at Los Angeles City College, Evans transferred to USC to be a backup.

Fred Lynn, USC baseball outfielder (1970 to 1973): The El Monte native was determined to be the first in his family to attend college. So while the New York Yankees drafted him in the third round of the 1970 draft for baseball, he opted for a football scholarship at USC. As a freshman, he was allowed to play baseball, but he enjoyed given the ability to play wide receiver, defensive back, kick, punt and return punts and kickoffs. He decided during his sophomore year to just concentrate on baseball, wearing No. 8, for teams that went 54-13, 50-13 and 51-13. Lynn was told the Dodgers would take him in the first round of the 1973 MLB draft, but they took a catcher out of Spokane, Ted Farr, hoping Lynn would still be available in the second round. The Red Sox took him one spot before the Dodgers in Round 2, 28th overall.

Aaron Boone, USC baseball infielder (1992 to 1994): Born in La Mesa, Boone was picked in the 43rd round by his California Angels right out of Villa Park High in 1991, but he decided to go to USC where he hit .302 with 11 home runs and 94 RBI in his career. That led to Boone becoming a third-round selection by the Cincinnati Reds in the 1994 MLB draft. The son of Angels catcher Bob Boone, Aaron put in a 12-year MLB career, worked at ESPN as a game analyst, and took over as manager of the New York Yankees in 2018. Perhaps Boone’s most remarkable feat came when he was with the Houston Astros in 2009. That March, he had to have an aortic valve replaced in his heart to treat a condition he battled with since he was at USC. Six months later, he became the first Major Leaguer in history to play after undergoing open heart surgery.

Kurt Suzuki, Los Angeles Angels manager (2026): After wearing No. 24 for the final two seasons of his MLB career as an Angels catcher (2021 and ’22, with a -0.9 WAR), Suzkui, a Cal State Fullerton Athletic Hall of Famer (wearing No. 3 for the College World Series champs of 2004), assumed the No. 8 as his new role of skipper.

Dwayne Jarrett, USC football receiver (2004 to 2006): Ninth in the Heisman voting after his junior season of ’06, Jarrett was a two-time All-American for the Trojans, catching 41 TD passes in 36 games, including an NCAA-best 16 in ’05. He became USC’s all-time receptions leader (216) and Pac-10 touchdown leader, sparking the Trojans to national championships with huge Rose Bowl performances, famously including a 205-yard game in the 2007 Rose Bowl where he was Offensive MVP. He was a second-round pick by Carolina in the 2006 NFL Draft.

Joe-Max Moore, UCLA soccer (1989 to 1992): Elected to the National Soccer Hall of Fame in 2013 and the UCLA Athletic Hall of Fame in 2014, Moore came to Westwood after starting four years at Mission Viejo High and was the seventh Bruin to record 100 career points (38 goals, 24 assists). Moore scored 11 goals, 10 assists and 32 points in his first season, helping to lead UCLA to the 1990 NCAA title. He led UCLA in scoring with 18 goals in 1991 and nine in 1992 and earned All-America honors both years. Moore went on to play with the U.S. National Team at the 1994, 1998 and 2002 World Cups and the 1992 Olympics. His 24 international goals rank fifth all-time in U.S. Soccer history. Moore, who also played professionally in Germany, England and in Major League Soccer from 1992-2004.

Have you heard this story:

Tommy Maddox, UCLA football quarterback (199o to 1991), Los Angeles Rams quarterback (1994), Los Angeles Xtreme quarterback (2001):

The fact Maddox led a Los Angeles pro football team to a title in the XFL at the turn of the century may have given him courage to continue trying to be a professional — finally seeming some success almost right away with Pittsburgh for a brief flash in 2002. Maddox only lasted two seasons at UCLA as a freshman and sophomore, enduring seasons of 5-6 in ’90 and 9-3 in ’91 that included a win in the John Hancock Bowl. His career — the first Pac-10 player to ever pass pass 5,000 yards by his sophomore year, to go with 33 TDs and 29 interceptions — led him to believe he was pro football ready. With the Rams in ’94, he got into five games (10 of 19 passing, o TDs, 2 INTs) on a 4-12 team where Chris Miller and Chris Chandler got a majority of the useless snaps.

Josh Johnson, Los Angeles Wildcats quarterback (2020):

At age 34, Johnson had a brief time as the starting quarterback for a professional Los Angeles football team. L.A.’s entry in the re-introduction of the eight-team XFL was short lived because the Wildcats’ first season, after a 2-3 start at Dignity Health Sports Park in Carson, was shut down due to the COVID-19 pandemic as part of the league’s stoppage. For the record, Johnson completed 81 of 135 passes for 1,076 yards and 11 touchdowns versus two interceptions with a 106.3 passer rating, best in the XFL to that point. But what further makes Johnson unique in pro football history is that, in an 18-year career, he played for a record 14 professional teams — despite throwing more interceptions (16) than touchdowns (13). Out of the University of San Diego (with Jim Harbaugh as his coach), Johnson was a fifth-round pick of the 2008 NFL Draft by Tampa Bay (ahead of Hawaii’s Colt Brennan). Johnson then journeyed to the San Francisco 49ers, the Sacramento Mountain Lions of the UFL, back to the NFL with Cleveland, Cincinnati, San Francisco (again), Cincinnati, the New York Jets, Indianapolis, Buffalo, Baltimore, the New York Giants, Houston and Oakland. The San Diego Fleet of the Alliance of American Football took him before he was back in the NFL with Washington and Detroit — then the stop in L.A. — and back to the NFL with San Francisco (a third time), New York Jets (a second time), Baltimore (again), Denver, San Francisco (a fourth time), Baltimore (a third time) and then, at age 39, with Washington (again) in 2025. He started nine NFL games over all that time.

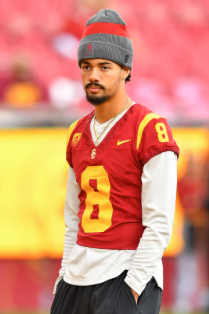

Malachi Nelson, USC football quarterback (2023): Follow this as long as you are able: The 6-foot-3, 195-pound Los Alamitos High standout started getting college scholarship offers when he was in eighth grade. To start his high school career, Nelson threw for more than 2,300 yards as a freshman and sophomore, and before his junior year, made a committed to play at Oklahoma. The Long Beach Press-Telegram Player of the Year as a junior threw for 2,690 yards and 33 TDs and signed a NIL deal with an L.A.-based hospitality firm. Nelson then de-committed to Oklahoma when coach Lincoln Riley went to USC, and switched his allegiance to the Trojans. After his senior year at Los Alamitos, after he threw for 2,898 yards and 35 TDs and helped the team to the CIF-SS Division 1 semifinals, Nelson was declared the best recruit in the nation by ESPN, and the five-star recruit was the California Gatorade Player of the Year. Enrolling early at USC, wearing No. 8 as one of the backups to Heisman winner Caleb Williams in the 2022 season, Nelson played one game — 1 of 3 passing, 0 yards, in the season-opening 56-28 win over San Jose State. By season’s end, it was evident he wouldn’t start in ’24 because Miller Moss won the job by virtue of a five-TD performance in the Holiday Bowl. So Nelson transferred to Boise State. Now a redshirt freshman, he lost the starting job to Maddux Madsen, came in for three games to complete 12 of 17 passes for 128 yards. So Nelson transferred to UTEP. For the 2025 season, Nelson started five games, completed 104 of 190 passes for 1,163 yards and eight TDs and nine interceptions, and the team was 1-4 in his starts as he was benched midway through their 2-10 season season. So Nelson transferred to Syracuse, according to his agent. The 2026 season will be his junior year.

Ray Guy, Los Angeles Raiders kicker (1973 to 1986): Starting with the franchise in Oakland in 1973, Guy became the first pure kicker to go into the Pro Football Hall of Fame and the first to be drafted in the first round of the NFL. His seven All-Pro seasons were all in Oakland before coming with the team to Los Angeles in 1982 for his final five seasons. The only time he fell below the 40-yard average mark came during the strike shortened (nine-game) ’82 season, when he averaged 39.1 yards. His three Super Bowl appearances included a title with the L.A. Raiders after the ’83 season.

Gary Carter, Los Angeles Dodgers (1991): Born in Culver City and starring at Sunny Hills High in Fullerton, Carter played 18 seasons as an 11-time NL All Star before the Dodgers signed him up at age 37, where he played 101 games as Mike Scioscia’s backup, the oldest player on the roster and also thought of as a positive influence on Dodgers outfielder and former Mets teammate Darryl Strawberry. Carter was inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame in 2003. In 2008, he managed the Orange County Flyers of the Golden Baseball League and led them to a title. Also, the 11th edition of the Merriam-Webster Collegiate Dictionary in 2021 credits Carter, who rarely used profanity, with the first recorded use of the term “f-bomb.,” when Carter used it in a 1988 Newsday story, explaining how he had only been thrown out of two games in his MLB career, both by umpire Eric Gregg.

We also have:

Manny Machado, Los Angeles Dodgers (2018)

Marques Johnson, Los Angeles Clippers (1984-85 to 1986-87) (Full bio at No. 54 post)

Bob Boone, California Angels catcher 1982 to 1988)

Doug Christie, Los Angeles Lakers guard (1992-93 to 1993-94) also wore No. 35 in ’92.

Dan Guerrero, UCLA baseball second baseman (1969 to 1973)

Karl Dorrell, UCLA football receiver (1982 to 1986)

Don Mattingly, Los Angeles Dodgers coach and manager (2008 to 2015)

Julie Ertz, Angel City FC soccer (2023)

Delisha Milton-Jones, Los Angeles Sparks (1999 to 2004, 2008-10)

Where does this fit in?

The time Don Rickles wore No. 8 for the Dodgers:

And for what it’s worth:

This can be seen on the wall at Philippe The Original Restaurant in Los Angeles:

Here is the explainer:

1 thought on “No. 8: Ralphie Valladares”