This is the latest post for an ongoing media project — SoCal Sports History 101: The Prime Numbers from 00 to 99 that Uniformly, Uniquely and Unapologetically Reveal The Narrative of Our Region’s Athletic Heritage. Pick a number and highlight an athlete — person, place or thing — most obviously connected to it by fame and fortune, someone who isn’t so obvious, and then take a deeper dive into the most interesting story tied to it. It’s a combination of star power, achievement, longevity, notoriety, and, above all, what makes that athlete so Southern California. Quirkiness and notoriety factor in. And it should open itself to more discussion and debate — which is what sports is best at doing.

The most obvious choices for No. 22:

= Clayton Kershaw, Los Angeles Dodgers

= Elgin Baylor, Los Angeles Lakers

= Lynn Swann, USC football

The not-so-obvious choices for No. 22:

= Bo Jackson, California Angels

= Hugh McElhenny: L.A. Washington High football; Compton College football

= Brett Butler, Los Angeles Dodgers

= Bill Buckner, Los Angeles Dodgers

= Dick Bass, Los Angeles Rams

= Raymond Lewis, Verbum Dei High basketball

= Raymond Townsend: UCLA basketball

The most interesting story for No. 22:

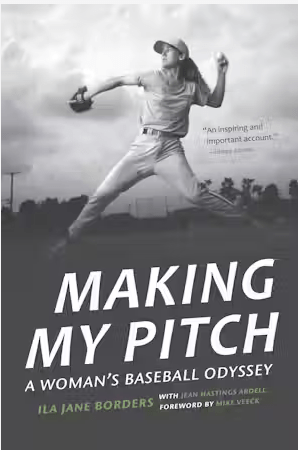

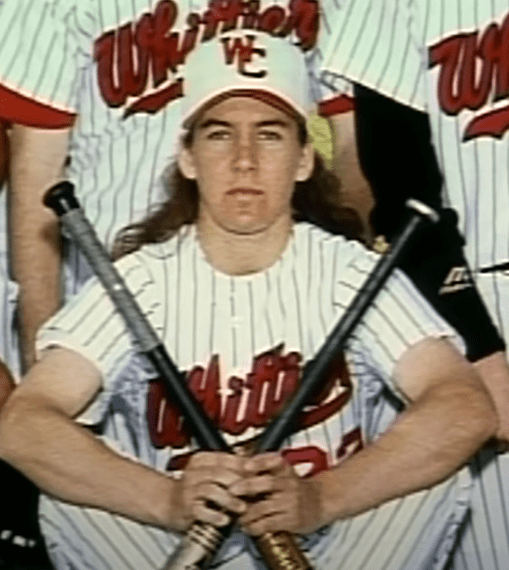

= Ila Borders, Whittier Christian High baseball pitcher (1989 to 1993)

Southern California map pinpoints:

Downey, La Mirada, La Habra, Bellflower, Costa Mesa, Whittier, Santa Ana, Long Beach

A camera crew from CBS’ “60 Minutes” chased down Ila Borders, and she was bordering on a panic attack.

The 23-year-old had become national news of sorts. It was 1998. She was about to become the first pitcher to start a game in a men’s professional baseball league, with the Duluth-Superior Dukes of the independent Northern League.

Her instincts were to push back on anything at this m0ment that could distract from her mental preparation.

In the prologue of her 2017 book, “Making My Pitch: A Woman’s Baseball Odyssey,” Borders explained how she had to retreat to the women’s restroom at the ballpark, jump into a stall and put her feet up so no one could detect she was there.

“I’m an athlete here to win,” she wrote. “Now get the hell out of my face. Would you tell a guy to smile? Growing up I heard about Don Drysdale, the Los Angeles Dodgers star right-hander of the 1950s and 1960s. I was crazy about Drysdale, who everyone said was the nicest guy around — except for the days he pitched. Then no one went near him. … I’ve been fighting for this since I was ten years old.”

By the time Mike Wallace had the chance to sit down with Borders, her family, friends, managers and teammates to do the story, Borders had a chance to explain.

“I’ve always had this fierce spirit to do what I want to do,” she said.

It want as far back to when she wore No. 22 for Whittier Christian High School in La Habra. Right about the time the movie “A League Of Their Own” had come out. There had been a template for women playing pro baseball, and Borders wanted in.

Continue reading “No. 22: Ila Borders”