“Pee Wee Reese:

The Life of a Brooklyn Dodger”

The author:

Glen Sparks

The publishing info:

McFarland

307 pages

$39.95

Released May 24, 2022

The links:

The publishers website

At Bookshop.org

At Indiebound.org

At Powells.com

At Vromans.com

At TheLastBookStoreLA.com

At PagesABookstore.com

At Amazon.com

At BarnesAndNoble.com

“Baseball’s Greatest What If:

The Story and Tragedy of Pistol Pete Reiser”

The author:

Dan Joseph

The publishing info:

Sunbury Press

298 pages

$19.95

Released Nov. 8, 2021

The links:

The publishers website

The authors website

At Indiebound.org

At Powells.com

At Vromans.com

At TheLastBookStoreLA.com

At PagesABookstore.com

At Amazon.com

At BarnesAndNoble.com

The review in 90 feet or less

Why not use this surprisingly rare opportunity for the Dodgers’ hosting the 2022 MLB All Star game on July 19 – it is the 92nd of these, only the second in L.A. since 1980 – to spread the news about a new 100 percent cotton Reyn Spooner commemorative shirt (available in 3XL) as well as chop up some history of the franchise representation in this exhibitionist exercise of non-extreme exertion, starting with this handy, dandy comb-over list we just uncovered.

== Steve Garvey, who could have been a Minnesota Twin if he signed with them after they drafted him out of his Tampa, Fla., high school in the third round of the 1966 MLB amateur selection, made nine starts for the National League in his 19-year career (1969-87). That is the most by any first baseman of either league and includes eight in a row from 1974 (when he made history to get in as a complete off-the-ballot write-in and then won the game’s MVP) through ’81. That was also the heaviest part of his 1,207 consecutive games-played streak. Then he represented the Padres in ’84 and ’85 (at age 35 and 36) to give him 10 appearances. Also MVP in ’78. His ASG career stats — 11 for 28 (.393), seven runs, two homers, two doubles, two triples, seven RBIs, 433 OBP and .821 slugging. Of all those who make up the all-time All-Star game starting lineup of appearances, he’s the only one not in the Hall of Fame.

You explain that one to all his kids.

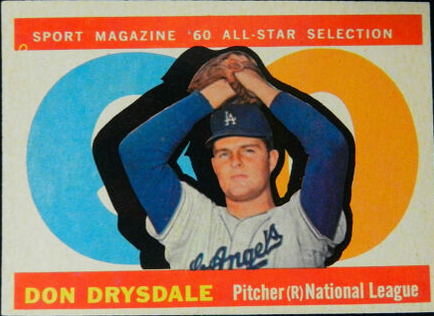

== Don Drysdale holds the record for most starts by a pitcher – five – to go with nine All-Star selections over his 14 seasons (1956 as a 19-year-old to 1969 at age 32). That includes 1959 when they played two All-Star games, the second one at the L.A. Coliseum. He started both of those as well as the second one in ’62, ’64 and ’68. He has a 2-1 record, 1.40 ERA, and the career ASG record for most innings (19 1/3) and strikeouts (19).

And no hit batters? Recheck those numbers.

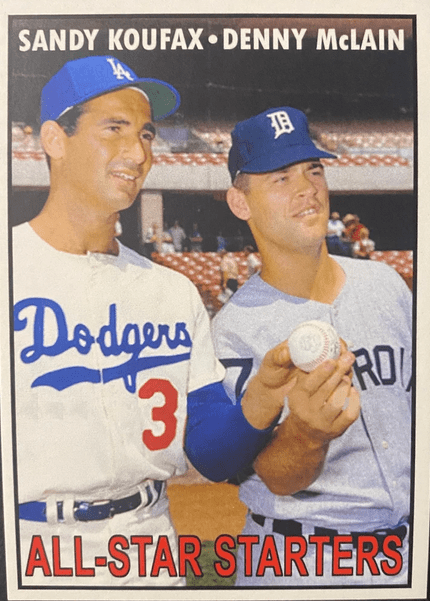

== Sandy Koufax batted right and threw left if you were bi-curious about his democratic approach to playing.

He was picked for six straight ASGs from ’61 (age 25) through ’66 (age 30) but made only four appearances – two in ’61 (at Fenway Park in Boston, which ended in a 1-1 tie because of rain, and at San Francisco’s Candlestick Park), plus ’65 (in Minnesota) and ’66 (in St. Louis), starting the last one in his final year active as a player.

He was left with just a 1-0 record with 1.50 ERA – one run over six innings, with three strike outs in 23 batters faced. What did the NL just not want to win?

== Clayton Kershaw has been picked for eight of them, every year from 2011 through 2019 (except for ’18). Six appearances. Has yet to make a start. Saddled with an 0-2 record, 4.50 ERA in six innings, facing 27 batters. Other Dodgers pitchers who have made the NL ASG team and then were named starters (aside from Drysdale and Koufax): Hyun Jin Ryu, Zack Grienke, Brad Penny, Hideo Nomo, Fernando Valenzuela, Don Sutton, Andy Messersmith, Ralph Branca, Dan Bankhead and Whit Wyatt.

What, Whit Wyatt?

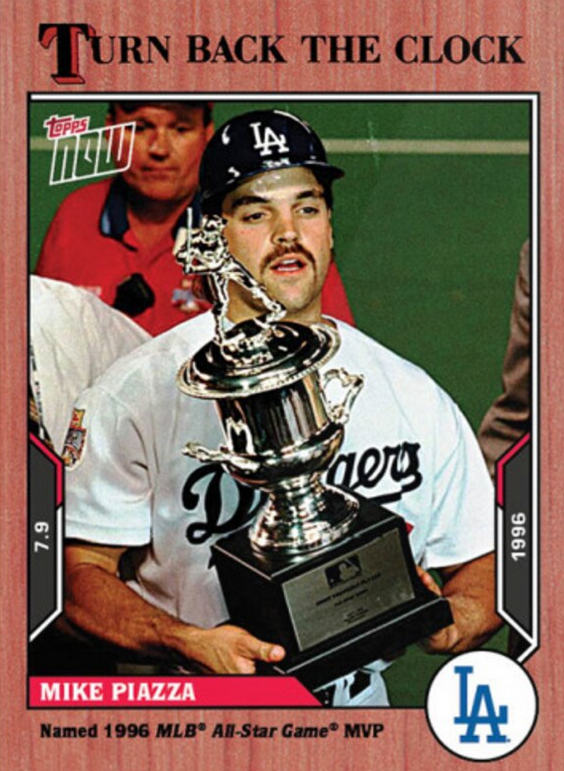

== Mike Piazza, a 12-time ASG pick, represented the Dodgers as the NL starting catcher in ’94, ’95, ’96 (game MVP) and ’97, plus a ’93 appearance off the bench during his Rookie of the Year campaign.

He was a keeper, right?

In the 1998 ASG at Coors Field, Piazza started as a member of … well, he began the season in L.A. (37 games), was shipped to Florida (five game), then moved for three unknowns to the New York Mets (on May 22), but still relevant enough to be picked for that year’s contest. He must have been a real difficult person to be around. Six more ASGs for those Mets and his 11 years worth of stats, with 10 straight starts: 6-for-25 (.240), 2 homers, 5 RBIs, 5 strikeouts. If only we could turn back the clock.

== Dodgers named MVPs of the game: Garvey twice (’74 and ’78), Piazza (’96), Maury Wills (’62, the first one) and Don Sutton (’77).

Wills, who would become the NL MVP that extended 165-game regular season with a record-setting 104 stolen bases (caught just 13 times, and a .299 average), didn’t start in either of those ’62 games – the Pirates’ Dick Groat did. In the sixth inning, As a pinch-runner for Stan Musial, Wills into the July 10 game at D.C. Stadium in Washington (where John Kennedy threw out the first pitch). Wills stole second and scored on Groat’s single. Staying in the game, Wills started the eighth with a single, somehow got to third on a single to short left field by Jim Davenport, then tagged and scored a fly ball in foul territory down the right field line by Felipe Alou. The NL won 3-1 — two of those runs almost single-handedly accounted for by Wills, a D.C. native a seven-time All Star pick from ’61 to ’65 (but not making it in ’64?) In the second ’62 ASG that year – Wrigley Field, 20 days later on July 30 – the L.A. Angels’ Leon Wagner was the MVP, starting in left field and going 3-for-4 with a fourth-inning home run off the Phillies’ Art Mahaffey.

As for Sutton: The 12th of his 23 seasons, when he led the NL in nothing, made him the starter at Yankee Stadium. He went the first three innings – no runs, one hit, four strikeouts, 11 batters faced. No one else went that many innings, and who today would even consider that load? Meanwhile, the NL was posting five runs against Jim Palmer with three homers (Garvey knocking him out in the third inning), staking Sutton to a 5-0 lead. WIth only four All-Star appearances (’72, ’73, ’75 and this one), Sutton got the starting nod by Sparky Anderson over Tom Seaver, Rick Reuschel, Steve Carlson (in his sixth ASG), Joaquin Andujar, John Candelaria, plus relievers Rich Gossage, Gary Lavelle and Bruce Sutter. No Mike Marshall? An All-Star in ’74 (with a Cy Young that year) and ’75, Iron Mike was wasting away in Atlanta and Texas that year before coming back with Minnesota for a stretch.

== Dodgers who’ve made the All-Star game you mostly likely have forgot about:

= In the 2000s: Relief pitcher Ross Stripling (’18: 1 1/3 IP, 3 ER, 4 H, 2 HR, losing pitcher in 10th inning, as NL manager Dave Roberts put him in over Kenley Jansen), second baseman Dee Gordon (2014, now Dee Strange-Gordon), relief pitcher Hung-Chik Kuo (’10), infielder Orlando Hudson (’09), pitcher Takashi Saito (’07), pitcher Odalis Perez (’02).

Way back in the 20th Century: Shortstop Jose Offerman (’95), infielder Mike Sharperson (’92), pitcher Mike Morgan (’91), second baseman Juan Samuel (’91), second baseman Willie Randolph (’89), pitcher Rick Rhoden (’76), outfielder Manny Mota (’73), infielder Billy Grabarkewitz (’70), catcher Tom Haller (’68), outfielder Norm Larker (’60, both games), outfielder Gino Cimoli (’57), pitcher Hal Gregg and outfielder Goody Rosen (’45, one of the great Jewish players of all time), outfielder Augie Galan (’43 and ’44) and infielder Pete Coscarart (’40). In 1933, infielder Tony Cuccinello was in the first All-Star Game, and the only Dodger representative at Comiskey Park.

== Dodgers who you likely forgot never made an All-Star team:

= Eric Karros, the Los Angeles Dodgers’ all-time leading home run hitter – 270 over 12 seasons – the ’92 Rookie of the Year and fifth in the MVP voting in ’95. He averaged 25 homers and 89 RBIs over that time. Those who did make the NL ASG team during the dozen years of Karros’ availability: Will Clark, John Kruk, Gregg Jefferies, Fred McGriff, Jeff Bagwell, Mark Grace, Andres Galarraga, Mark McGwire, Sean Casey, Todd Helton and Ryan Klesko.

(For the longest time, the Angels’ Mike Salmon was the franchise leader in home runs with 299, plus 1,016 RBIs, and also never was made an AL ASG pick over his 14 seasons as a California/Anaheim/Los Angeles cap wearer from 1992 to 2006).

= Kirk Gibson (like Karros, wore No. 23): Invited twice, in ’85 and ’88, but he declined. So … that’s on you, Gibby. During his NL MVP year of ’88, he hit .290 with 25 homers, 76 RBIs and 31 stolen bases (not to mention that stuff in the post-season). BTW: In his 17 MLB seasons, he never led the league, AL or NL, in any notable statistical category. In his first year of Baseball Hall of Fame eligibility, 2001, he had just 2.5 percent of the vote and was dropped from then on. He would win the 1984 AL ALCS MVP and was the 2011 National League Manager of the Year with Arizona.

Of note: Released last summer was “Game Won: How the Greatest Home Run Ever Hit Sparked the 1988 Dodgers to Game One Victory and an Improbable World Series Title,” by Steven K. Wagner (Sunbury Press, 184 pages, $16.95, released July 20, 2021). Wagner also wrote the much appreciated “Seinsoth: The Rough and Tumble Life of a Dodger“).

Something we learned from the excellent “How to Beat a Broken Game: The Rise of the Dodgers in a League on the Brink” by Pedro Moura were from these two paragraphs:

“In John Helyar’s 1994 book, ‘Lords of the Realm: The Real History of Baseball,’ he argues that the day MLB owners collusion likely ended was on Oct. 15, 1988 – when Kirk Gibson, the Dodgers’ prized free-agent off-season signing, who would win the regular season MVP award, created what is still considered the greatest moment in Los Angeles sports history. ‘Nobody who witnessed that scene – a fist-pumping Gibson rounding the bases, his teammates mobbing him at home plate, Dodgers fans filling the night with a roar – could ever again say that no free agent was worth it.'”

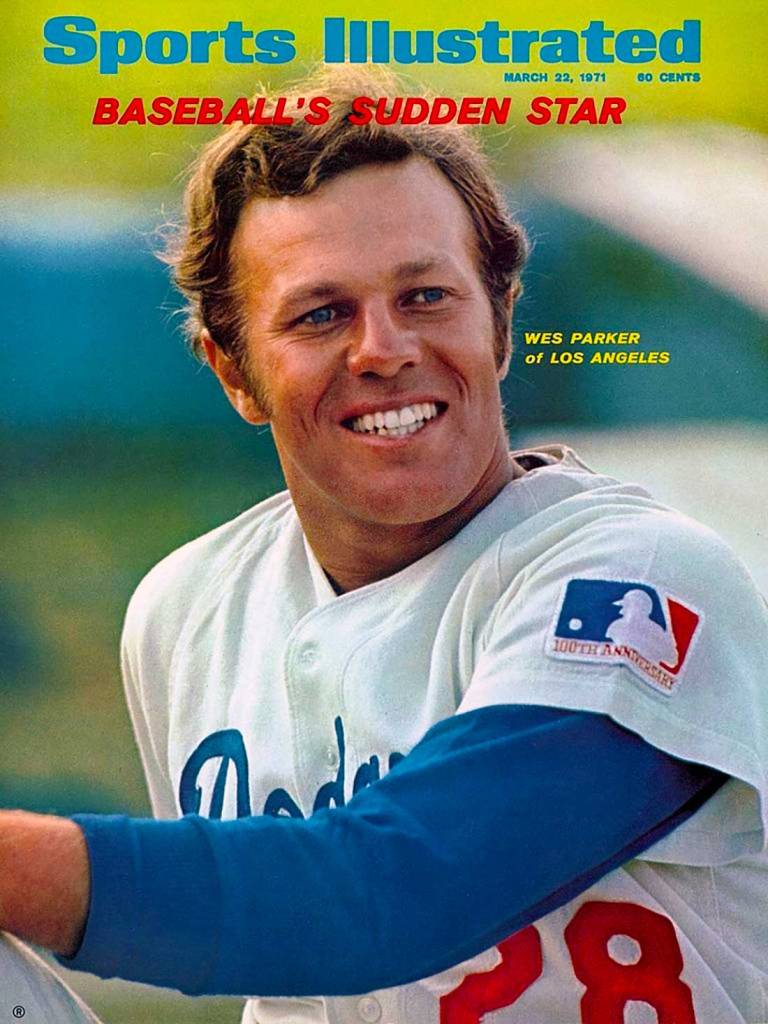

= Wes Parker (like Karros, owned a first baseman’s mitt): Posted nine more-than-worthy seasons from ’65 to ’72, winning six Gold Gloves. Fifth in the league in hitting in 1970 with a .319 mark (plus a league-leading 47 doubles and a career-best 111 RBIs, fifth in the NL MVP voting). He was given the 1972 MLB Lou Gehrig Memorial Award to “honor the Major League Baseball Player who best exemplifies the spirit and character of Lou Gehrig, both on and off the field.” At least Greg Brady knows the true value of Paker, who made an early 1971 baseball season cover of Sports Illustrated as a “sudden star” at age 31. Jinx?

************

Sure, right … so what’s the now deal with Harold Peter Henry “Pee Wee” Reese and Harold Patrick “Pistol Pete” Reiser?

Throw the books at us. There exist two new bios about these Brooklyn stars.

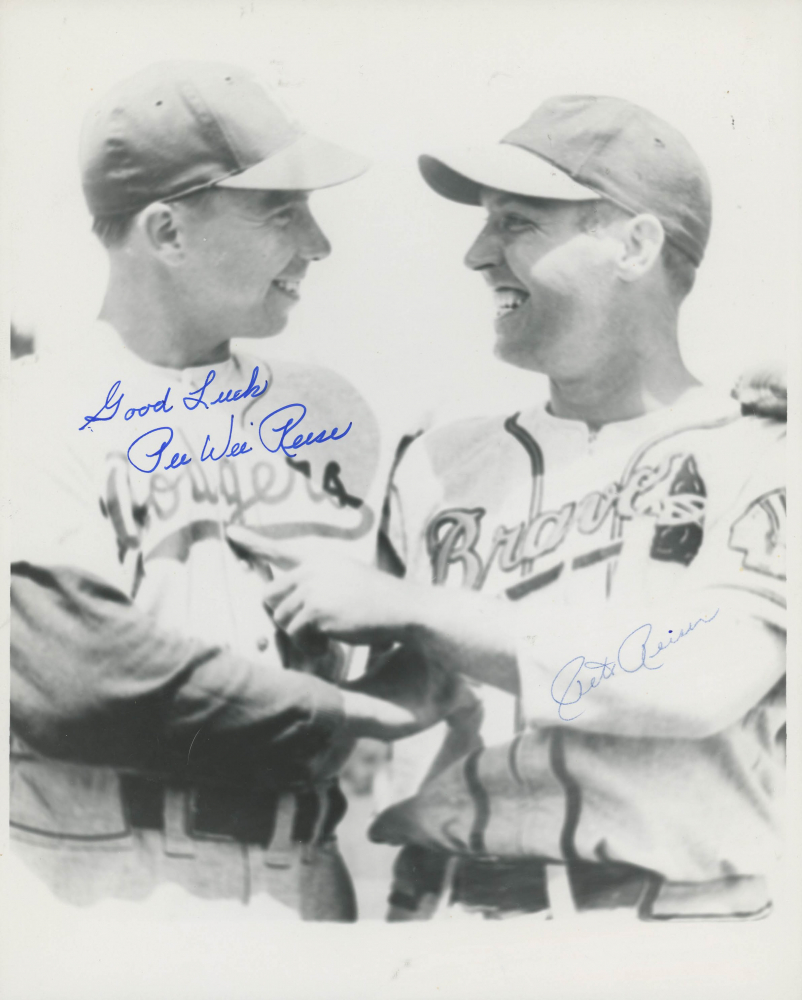

Born less than a year apart, Reese and Reiser seemed to relish their time as Brooklyn Dodgers teammates for six seasons — first in 1940, ’41 and ’42, then a three-year departure to serve in World War II, then back together for ’46, ’47 and ’48.

That can be a baseball lifetime.

They were a pair of 22-year-olds starting on the Dodgers’ 1941 100-win World Series team that lost to the Yankees. Both went 4-for-20 in the Fall Classic, and Reiser hit the team’s only homer.

By next summer, both on the ’42 NL All Star team at the Polo Grounds in New York in the AL’s 3-1 win– Reiser started and hit third in center field during (here is a complete radio play-by-play of the game).

They were also together in the ’46 NL All-Star team at Fenway Park in Boston, the game’s revival a year after it was canceled because of the war. That game’s 13th edition, a 12-0 AL win, was made famous when Ted Williams hit a homer off Rip Sewell’s “Eephus pitch.”

Back from Army military work, Reiser was 27 in ’46, and would lead the league with 34 stolen base — seven of them, steals of home — finishing ninth in MVP voting. He had finished second in ’41 and fifth in ’42. Reese, also 27 in that game, turning 28 a couple weeks later, returned from his Navy stint and was sixth in MVP voting for the 96-win team that finished two games out of winning the pennant.

Reese wasn’t the Dodgers’ first starting ASG shortstop — that would be Leo Durocher in 1938. But in his 16-year MLB career that ended at age 39 as a player/coach in L.A. for one abbreviated season to help ease in Wills, Reese was named to 10 All-Star teams – a franchise record — starting three.

Reese made that first ASG at age 23, then nine in a row from age 27 through 35 (’46 through ’54). In the ’49 game — the one and only at Ebbets Field in Brooklyn — he started and batted first, ahead of second baseman and teammate Jackie Robinson. That was also the first time an African-American was picked to play (along with the Dodgers’ Roy Campanella and Don Newcomb, plus Larry Doby for the AL).

The ’49 game, which was also the first of Gil Hodges’ eight ASG picks (with only one start, in ’51) only gets minor mention in Chapter 10, titled “That’s Why We Called him ‘Captain.’) It includes a line by The Sporting News’ Harold Burr: “Captain Pee Wee Reese is having one of his greatest years at short, which is just about all that could be said in praise of the greatest shortstop in the game.” Reese went 0-for-5.

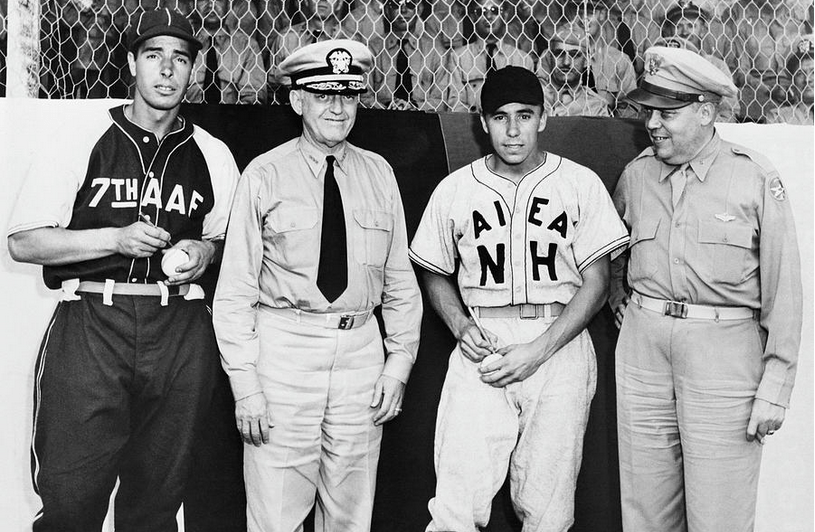

The pieces of Reese’s life you’ve come to see portrayed in movies like “42” or recall from “The Boys of Summer” all get otherwise cursory recognition, very brief at times — such as his time in the Navy playing baseball at bases around the U.S., pushing Roy Campanella in his wheelchair out on the field before the 1959 tribute at the Coliseum).

Not all that much either about his national TV game analysis, the Hall of Fame vote in ’84 (he’d go in with Drysdale as it happened) all up to his passing in 1999.

“Pee Wee Reese, the former ace marble shooter from Louisville, made his mark as both a person and as a player,” Sparks concludes, without much of a spoiler alert. “He led the Dodgers both on and off the field. One story goes that a young fan saw him in a hotel lobby and asked another player, ‘What does he do?’ The player said, ‘Anything you want him to.'”

And let’s just end it at that.

In detailing the life and times of Reiser, Joseph seems to have much intriguing story narrative to sift through — and it earned him 2022 SABR recognition for best research work on the Brooklyn Dodgers.

Aside from his NL ASG start in ’42, Reiser also started in center field and hit third in the ’41 ASG at Briggs Stadium in Detroit. Please note: Hall of Famer and eight-time All Star center fielder Duke Snider also only started two NL ASGs in back-to-back years of ’54 and ’55.

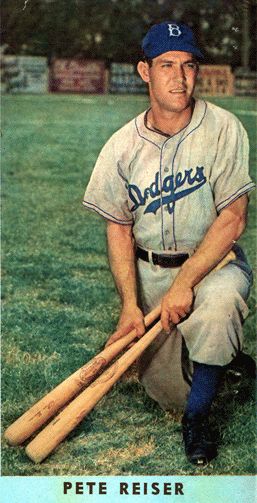

Reiser, the NL batting champ in ’41 at .343 with a league-best 117 runs and 17 triples, lasted just those six Dodgers seasons, discarded in ’48. He was out of the game by ’52, age 33, trying to come back with the Boston Braves, Pittsburgh Pirates and Cleveland Indians.

The problem was Reiser’s inability to do his own stunts.

Reese even said in 1972: “Pete was better than Stan Musial, I think. He could do more things than Stan. He’d run through a brick wall to get a ball — and did try a couple of times.”

Joseph writes it is hard to document all the incidents, “but sports writers of the time said Reiser was carried off the field 11 times during his career.

Joseph, who in 2019 also wrote “Last Ride of the Iron Horse” about Lou Gehrig’s final year in the Yankees lineup, kept reading about how Reiser’s heroics were passed down through the years to the extent that, he would often still be a bit loopy from a collision, but volunteer to pinch hit days later and come up with a game-winning wack.

“My journalistic soul raised its hand and asked: Are these stories true?” Joseph continues in the intro. “If they are true, why would Reiser push himself to such extremes? What maniacal drive caused him to risk his career, health and life for a baseball game? Moreover, why would the Dodgers’ decision-makers let him even try? I had to find out. That’s the first reason I’m writing this book.”

Because, as he reminds us, Reiser was “set to become a central figure in the national pastime. He was at the right place at the right time — New York, baseball and media capital of the world, at the start of the most drama-filled period in the game’s long, long history.”

Joseph is wise enough to connect Reiser’s his style of play to today’s gatecrashers. At least most now don’t have to contend with flagpoles, bullpen mounds or stone monuments, and have padded wood walls rather than brick facades to contend with.

The worst Ebbets Field had was an iron exit gate in center field that Reiser cut his back on in ’41.

During a Dodgers-Nationals game in 2013, Joseph brings up a moment when Bryce Harper was chasing a fly ball to right field and charged face-first into the right-field wall and scoreboard, bringing on an ugly gash on his neck that required 11 stitches.

“All I can think of … is a name that is a legend in Dodger history, an outfielder named Pete Reiser,” Vin Scully said on the broadcast.

It led the L.A. Times’ Jim Murray to write about Reiser: “Every ballpark in America has a Pete Reiser memorial: The warning track in the outfield.”

Sigh.

Joseph gets the most of the subject by devoting the final Chapter, the 12th, to Reiser’s legacy. It was revived a bit when Donald Honig and Lawrence Ritter included Reiser in their 1981 book, “The 100 Greatest Baseball Players of All Time.” He touches on how Reiser had an influence on Bernard Malamud’s creation of Roy Hobbs in “The Natural.”

Joseph also correctly writes that while Reiser will likely never be inducted into Baseball’s Hall of Fame, “whether measured in terms of statistics, awards, pennants or overall impact, Pete’s actual accomplishments do not rise to the level of a typical Hall of Fame outfielder, even with compared to low-tier what-where-they-thinking picks like Chick Hafey and Harold Baines … But before the walls got in the way, Pete was starting to build a bona-fide Cooperstown resume.”

Sigh again.

How it goes in the scorebook

8-6 double play output.

Neither are knock-your-blue-socks-off when it comes to prose — think of Kosyta Kennedy and his latest Jackie Robinson book, which is why one is apt to pick it up in the first place no matter what you already know about the subject. It’s the research that sells it as another SABR-sort of project that heralds documentation gathering over turning a phrase.

Continue reading “Day 26 of 2022 baseball books: The Dodgers’ star-struck history, with Reese and Reiser (both named Harold) as heralded entry points”