“Don Drysdale: Up and In

The Life of a Dodgers Legend”

The author: Mark Whicker

The details: Triumph Books, 256 pages, $30, released Feb. 18, 2025; best available at the publishers website and Bookshop.org.

A review in 90 feet or less

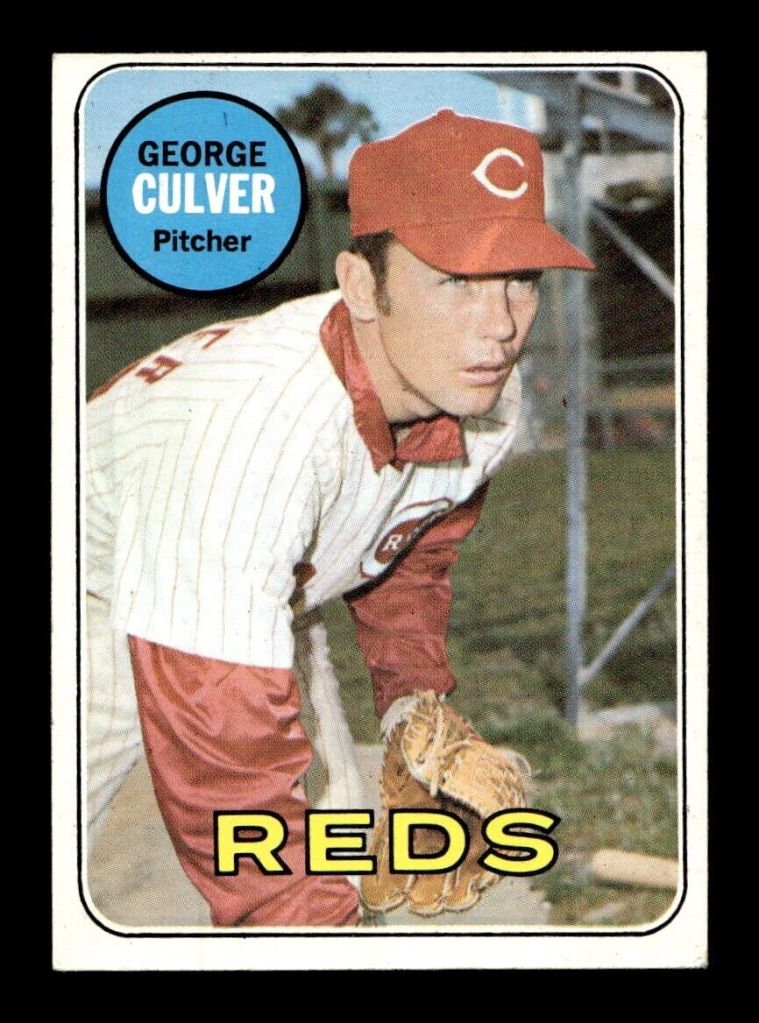

Growing up in Bakersfield in the ’50s and ’60s, George Culver wanted to be like Don Drysdale.

In his new autobiography, “The Earl of Oildale” — the title spins off a nicknamed pinned on him by Dodgers’ broadcaster Vin Scully — Culver explains how it was as a Little Leaguer that he first saw Drysdale play baseball in his hometown.

It was 1954. Drysdale, who had done well as a second baseman on his Van Nuys High team, hadn’t taken up pitching until his senior year as something of a fluke. His arm, and temperament, rocketed him to a pro career immediately after graduation. The 17-year-old signed a contract and went a hundred miles north as a member of the Bakersfield Indians, which were the Brooklyn Dodgers’ C-level Cal League team. He and his family almost decided to take Pittsburgh GM Branch Rickey up on an offer to join the Pirates’ Hollywood Stars of the Pacific Coast League first as a way to the major leagues, but the destination seemed filled more with potential potholes.

In Bakersfield, Drysdale managed an 8-5 mark and 3.45 ERA in 14 starts, including 11 complete games. That somehow put him on a fast track to the big leagues — next stop was one year at Triple-A Montreal in ’55 as the Dodgers won their first World Series title, and, by ‘56, a spot in the Brooklyn rotation as a 19-year-old.

Culver, a star athlete at North High in Bakersfield and then at Bakersfield College, could see still Drysdale in person pitch at the L.A. Coliseum and then Dodger Stadium after the franchise made its move from Brooklyn to Los Angeles. By 1966, Culver reached the big leagues himself as a 22-year-old with Cleveland.

Now, two seasons later — in the magical 1968 “Year of the Pitcher” that included Drysdale establishing his MLB-record 58 2/3 scoreless innings streak — Culver was in the Cincinnati Reds’ rotation, en route to posting a career-high 226 innings in 35 starts. Just a month after Drysdale set his streak with six straight shutouts, the Dodgers and Reds faced off on a Friday night in early July at Dodger Stadium.

It was Drysdale vs. Culver.

“I was about to get a chance to not only pitch against him, but hit against him and that nasty side-arm deliver,” Culver writes on page 53 of his book. “What a thrill (why me?)”

The game was scoreless through 10 innings — and Drysdale and Culver were still pitching.

Drysdale’s line against a Reds’ lineup that included Pete Rose in left field, Tony Perez at third base, Johnny Bench catching and Lee May at first: Five hits, one walk, three strike outs.

Culver gave up five hits as well, walking two, striking out two. Drysdale, who may have also been the most feared bat in the Dodgers’ lineup, grounded out three times against Culver. Ken Boyer pinch hit for Drysdale in the bottom of the 10th and struck out — the last batter Culver faced. So went the Dodgers’ offense.

Culver came out for a pinch hitter as well in the top of the 11th-inning as 23-year-old Don Sutton came on in relief of Drysdale. Against those two future Hall of Famers, the Reds won, 2-0, on May’s run-run double in the 12th inning.

It was a split decision in Drysdale vs. Culver — actually, a no-decision for both.

“This was, without a doubt, the best game I ever pitched in the major leagues,” wrote Culver.

Consider that four starts later, Culver tossed a no-hitter against the Phillies at Connie Mack Stadium.

He had five walks in that one and actually trailed, 1-0, in the second inning because his teammates would make three errors behind him in total.

Continue reading “Day 3 of 2025 baseball book reviews: Dutiful Devotion to Double D” →