This is the latest post for an ongoing media project — SoCal Sports History 101: The Prime Numbers from 00 to 99 that Uniformly, Uniquely and Unapologetically Reveal The Narrative of Our Region’s Athletic Heritage. Pick a number and highlight an athlete — person, place or thing — most obviously connected to it by fame and fortune, someone who isn’t so obvious, and then take a deeper dive into the most interesting story tied to it. It’s a combination of star power, achievement, longevity, notoriety, and, above all, what makes that athlete so Southern California. Quirkiness and notoriety factor in. And it should open itself to more discussion and debate — which is what sports is best at doing.

The most obvious choices for No. 31:

= Mike Piazza: Los Angeles Dodgers

= Cheryl Miller: Riverside Poly High basketball, USC women’s basketball

= Ed O’Bannon: UCLA basketball

= Reggie Miller: UCLA basketball

= Kurt Rambis: Los Angeles Lakers

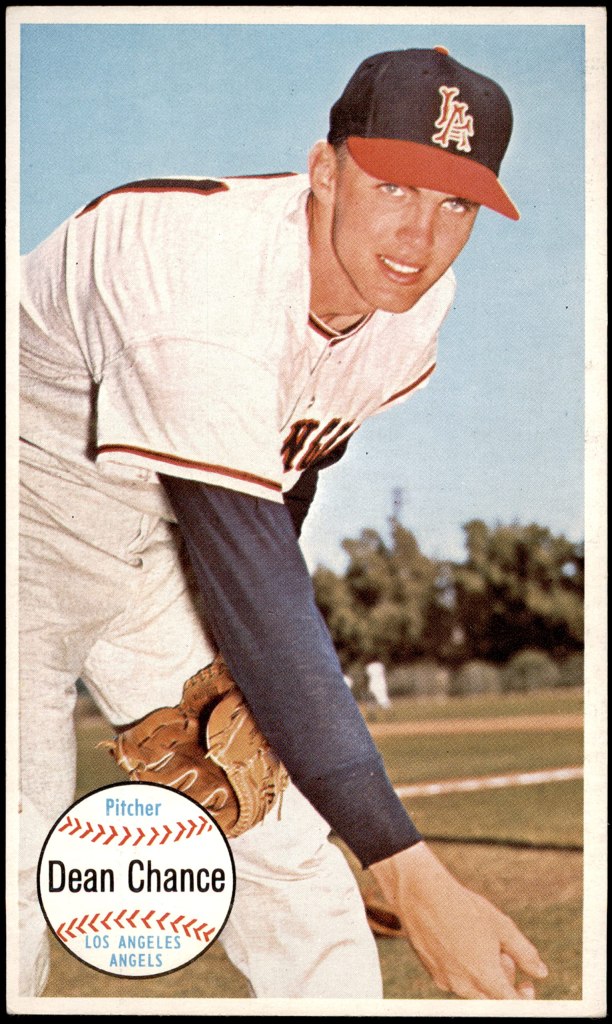

= Dean Chance: Los Angeles/California Angels

The not-so-obvious choices for No. 31:

= Carnell Lake, UCLA football

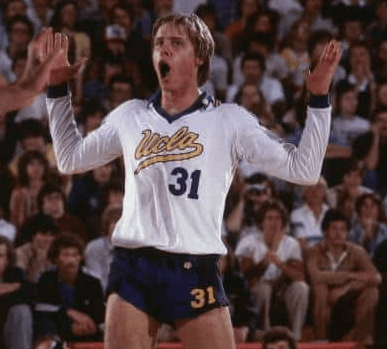

= Karch Kiraly: UCLA volleyball

= Spencer Hayward: Los Angeles Lakers

= Guy Hebert: Mighty Ducks of Anaheim

= Swen Nater: UCLA basketball

= Chuck Finley: California/Anaheim Angels

= Jason Collins: Harvard-Westlake High School basketball

= Joe Grahovac: Fullerton College basketball

The most interesting story for No. 31:

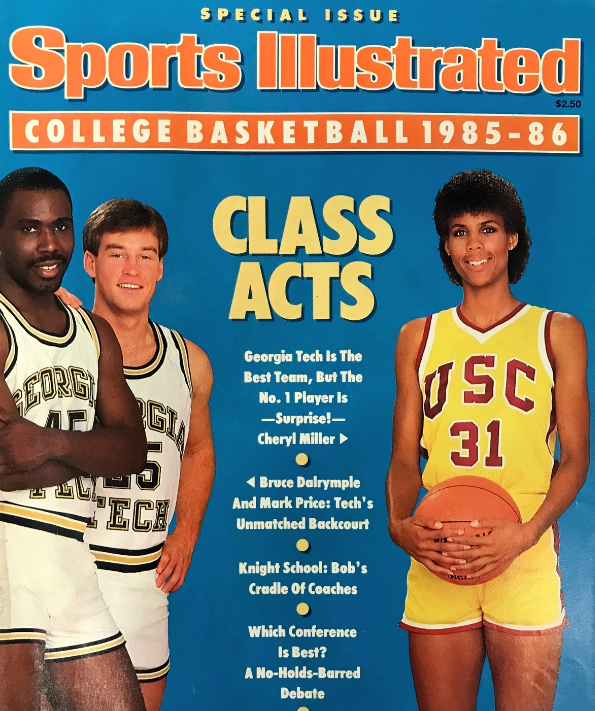

Cheryl Miller: USC women’s basketball (1981-82 to 1985-86) via Riverside Poly High

Reggie Miller: UCLA basketball (1983-84 to 1986-87) via Riverside Poly High

Southern California map pinpoints:

Riverside; Westwood (UCLA); downtown L.A. (USC)

During the 2005 season, rumors percolated that Reggie Miller was ready to retire from the NBA after a hot-shot, 18-year run, all of them with the Indiana Pacers. He was coming up on 40 years old. It made sense.

TNT reporter Cheryl Miller denied the story was true.

She was even a bit adamant about it as she told her broadcasting partner on air to cease and desist with reporting such inaccurate information. Besides, if anyone should know, would be her.

Two weeks later, during a Lakers-Pistons telecast, Cheryl Miller reported on TNT that Reggie Miller would, in fact, be retiring. Reggie had told his coach, Rick Carlisle, first. Then he gave the scoop to Cheryl.

Proving again: Older sisters protect younger brothers, no matter what their age or their eventual Basketball Hall of Fame status.

For both of them.

Reggie Miller – aka Uncle Reg, The Knick Killer, Killa, Funk and Mighty Mouth, as they are listed on his BaseballReference.org biography – was born 19 months after his sister Cheryl. They were the last two of the five kids from Saul and Carrie Miller at their Riverside home. Included in that was oldest son, Darrel, a catcher for the California Angels (who wore No. 32, 1984 to 1988).

As basketball players, Cheryl was the bigger deal even if, at 6-foot-2, she was at least five inches shorter than pencil-thin Reggie in their adult lives.

It was Cheryl who once scored 105 points in a 32-minute game in 1982 for Riverside Poly High – the same night Reggie scored 40 in a game for the boy’s varsity team. Guess who got the bigger headlines?

In leading Poly to a 132-4 record, averaging 37.5 points a game, Cheryl was also said to be the first female player to dunk in a game. She was the national High School Player of the Year. As a junior and senior.

She picked USC to continue her play, a place making a name for itself with the McGee twins on the front line. USC won a national title her freshman year — the Trojans were 31-2. And in her sophomore year — the Trojans were 29-4. She took a detour to win a gold medal for US basketball in the 1984 Olympics in Los Angeles, and won the Naismith Player of the Year Award three times.

There’s little argument, even today, she is among the most dominant players in women’s basketball history. In October of 2025, in honor of the 50th anniversary of the women’s basketball poll, The Associated Press assembled a list of the greatest players since the first poll in 1976. Without ranking them, Miller was included on the AP first team with Caitlin Clark, Diana Taurasi, Brenna Stewart and Candace Parker.

“I grew up watching Cheryl Miller play,” said Chicago native Parker, who ended up a star with the WNBA’s Los Angeles Sparks. “She’d be No. 1. My dad was like ‘This is who we wanted you to be.’ I’m honored to be on this list with her.”

In March of 2020, HBO Sports created a documentary celebrating Miller, and it included NBA analyst Doris Burke exclaiming: “She was a bad … mother … fucker.” (Even if our story in the L.A. Times misconstrued that quote).

That nickname is not on any of Cheryl Miller’s internet biography stats pages. It should be.

For her high school, college and Olympic GOAT status, Cheryl Miller may have been as overqualified as anyone to be inducted into the Basketball Hall of Fame in 1995, the Women’s Basketball Hall of Fame in 1999 and the FIBA Hall of Fame in 2010.

She wore No. 31 through high school and college, as USC retired it in 1986.

She didn’t have a WNBA to go to after college, despite the idea she might try out for a men’s pro league like UCLA’s Ann Meyers once did. Worse, Miller suffered a bad knee injury in a pickup hoops game at USC. She went into coaching (at USC, in 1993 and ’94 and the WNBA’s Phoenix Mercury first season in 1997 at age 33, also their GM, lasting four seasons) and always had broadcasting to fall back on. She even circled back to coach at Cal State L.A. in 2018.

Reggie also wore No. 31 simultaneously during his four years as an All-American at UCLA, no doubt a career fueled by continuously losing one-on-one games back home growing up against Cheryl. As well as overcoming a hip deformity that made him wear corrective braces on both legs for years to build strength. Playing against Cheryl helped him develop his high-arching shot. And they apparently had a side hustle at the local playground when possible.

At UCLA he finished second all time in points scored at 2,095, second then only to Lew Alcindor. He set a school record with 33 points in one half.

Reggie kept the number through his NBA career – drafted 11th overall by Indiana, even as GM Donnie Walsh was booed by fans. He lasted nearly 1,400 games in the regular season and 144 in the playoffs and when he did retire – as Cheryl reported – he had the most 3-point field goals – 2,560, until Ray Allen and Steph Curry passed him. But it was Reggie Miller who made the 3 an effective weapon at a time when the NBA was trying to figure out how this ABA rule might spice up the game.

And, whatever he could do to spice up a game at Madison Square Garden and upset Spike Lee — like scoring eight points in nine seconds to win Game 1 of the 1995 Eastern Conference semifinals — all the bigger stage to do it. If only he could have willed the Pacers to an NBA title in 2000 when they faced the Lakers. The Larry Bird-coached team lost to the Kobe Bryant-Shaquille O’Neal squad, even as Miller led the team with 33 points in a 100-91 Game 3 win at Conseco Fieldhouse in Indianapolis, and scored 35 the next game in a 120-118 overtime loss. Lakers fans seemed to be so upset Miller didn’t get his title that they turned over police cars and set fires to dumpsters outside Staples Center after the Lakers wrapped up in Game 6.

Reggie Miller would also win Olympic gold in 1996, be voted into the Basketball Hall of Fame in 2012 and named to the NBA’s 75th Anniversary Team in 2021.

UCLA retired his No. 31 in 2013, seven years after the Pacers did so. (What number did he wear at Riverside Poly? Checking in on that one).

Both Cheryl and Reggie Miller became TV broadcasters because of their love of talking.

Reggie, as a game analyst, or Cheryl, as a sideline reporter, might even say the same phrase at the same time on a TNT broadcast: “Are you kidding me?”

“The family will always tell you the truth, and the good thing about having a sister at the same network, we can bounce ideas and thoughts off one another,” Reggie told us about Cheryl helping him as a broadcaster, which he started actually doing WNBA games for the Lifetime Network in the 1980s. “When I first started, Cheryl was trying to get me to be even more opinionated, and I wasn’t sure I wanted to come out and start hitting it that hard right away.

“TNT gives us the chance to voice our opinions. I’m not doggin’ others – like ESPN – but I think we’re so off the cuff and unscripted people believe it a little bit more.”

Fox Sports basketball analyst Chris Broussard once said about the dynamic duo: “Cheryl Miller and her Hall of Fame brother, Reggie, you’ve probably heard of him, are probably the greatest sibling combo in the history of basketball. Think about it. You got Steph and Seth Curry. Seth’s got to pick it up a little bit. Then you got Marc and Pau Gasol. Pau’s going to be a Hall of Famer. But will Marc? Uh. I don’t know about that. But Cheryl and Reggie? Both of them in the Hall of Fame.”

And with that is 31 flavors of fun.

Who else wore N0. 31 in SoCal sports history? Make a case for:

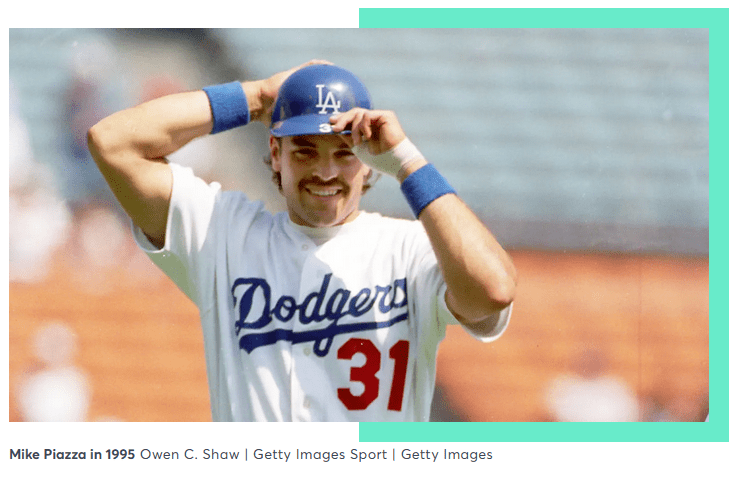

Mike Piazza, Los Angeles Dodgers catcher (1993 to 1998):

What would have happened if the Dodgers’ Fox ownership hadn’t traded him (without the GM’s knowledge) to Miami (and then to the Mets) in the middle of the 1998 season as his contract was about to expire? Would his Hall of Fame plaque have sported an L.A. logo? We’ll never know. Will the Dodgers ever retire his No. 31 now that he’s in Cooperstown? Doesn’t seem so.

The kid who Tommy Lasorda asked the Dodgers to pick No. 1,390th overall in the 62nd round of the 1988 MLB draft as a favor to his family ended up as one of the greatest hitting catchers in the game’s history. He started his rookie spring training of 1992 sporting No. 60 — that’s how special he was. By the time he came up for 21 games in September, they gave him No. 25. That didn’t stick either.

His switch to No. 31 came in his 1993 Rookie of the Year season at age 24 (149 games, 35 homers, 112 RBIs, .318 average) and was the start of six seasons in a row as an NL All Star (the ’96 game’s MVP) and six Silver Slugger awards. In his last full season with the Dodgers, he set a Los Angeles’ single-season record with a .362 batting average, playing 152 games, and accounting for 40 homers, 124 RBIs, 201 hits and 104 runs scored — all career highs. He was second in the MVP voting in ’96 and ’97. His .346 average in ’95 is second-all time in L.A. franchise history (tied with Tommy Davis’ in ’62). Piazza ended up playing one more year (seven) in New York than he did in L.A. (six and a half), and the NY log is on his Cooperstown plaque.

Ed O’Bannon, UCLA basketball forward (1990 to 1995):

Verbum Dei High to Artesia High to a 1995 NCAA title with UCLA (30 points, 17 rebounds vs. Arkansas) with his younger brother Charles. He even played for the ABA’s Los Angeles Stars (2000-2001, wearing No. 31). In the UCLA Hall of Fame in 2005. And his class action suit at the NCAA started the whole NIL rage. We enjoyed meeting up with him to discuss his new book as well on a trip to Las Vegas during the 2018 Pac-12 basketball tournament.

Carnell Lake, UCLA football linebacker (1985 to 1988):

Inducted into the UCLA Athletic Hall of Fame in 2000, Lake made 45.5 tackles for loss (No. 1 in school history) and 25.5 sacks (No. 4 overall) as UCLA went 37-9-2 during his four years and won the Rose, Freedom, Aloha and Cotton bowls. At Culver City High, as a running back and linebacker, he led the state in rushing at the start of the season after gaining 956 yards and scoring 12 touchdowns in four-and-one half games.His 12-year NFL career was spent wearing No. 37 — which his son, Quintin, wore as a defensive back for the Bruins from 2017 to 2023 before he was drafted by the Los Angeles Rams.

Kurt Rambis, Los Angeles Lakers forward (1981-’82 to 1987-’88, 1993-’94 to ’94-’95):

On four NBA title teams as their enforcer wearing his black horned-rimmed glasses and shaggy hair, Rambis would have been fit to be one of hockey’s Hanson brothers if the NBA had its version of “Slap Shot.” A Lakers assistant, head coach and assistant GM after he was done playing, Rambis may be best remembered perhaps for his reaction to being clotheslined by Boston’s Kevin McHale in Game 4 of the 1984 NBA Finals at the Forum.His return to the Lakers for the 1993-’94 season saw him wear No. 18 as his previous No. 31 was being worn by backup center Sam Bowie.

Dean Chance, Los Angeles/California Angels pitcher (1961 to 1966):

From ’63 to ’66, the only pitcher not named Sandy Koufax to win the Cy Young Award — then given to one pitcher in all of baseball — was Chance, who also became the youngest winner at 23 when he posted a 20-9 record in ’64 with a league-best 1.65 ERA in 278 innings. And his home field was Dodger Stadium. His league-best 15 complete games included 11 shutouts, and five of them were 1-0 victories. Chance was inducted into the Angels Hall of Fame in 2015, two months before his death.

Chuck Finley, California/Anaheim Angels pitcher (1986 to 1999): Holds team records for games started, wins (165) and innings pitched. MLB All Star in 1989 and 1990.

Richard Washington, UCLA basketball (1973-1976): Played on teams that went 26-4, 28-3 and 28-4 and made three Final F0urs. The Most Outstanding Player of the 1975 NCAA Tournament. In the UCLA Hall of Fame.

Karch Kiraly, UCLA volleyball outside hitter and setter (1979 to 1982): UCLA has retired the number of perhaps the greatest U.S. volleyball player ever — a four-time All-American out of Santa Barbara who was part of three national titles with the Bruins (’79, ’81 and ’82, named the Most Outstanding Player in ’81 and ’82), winning gold medals at the 1984 and 1988 Olympics, as well as the ’96 Games in the first beach competition. That has to account for something for someone who wanted to grow up and be a biochemist like his dad. On the beach, Kiraly was even perhaps more dominant with 148 career wins over 28 years of competing with 13 different partners (74 titles with Kent Steffes) and going into his 40s (and a six-time AVP Most Valuable Player). The Volleyball Hall of Fame made a spot for him in 2001.

Guy Hebert, Mighty Ducks of Anaheim goalie (1993-94 to 2000-01): The first expansion draft pick of the franchise when it started in 1993 and the last of the original Ducks left when the team waived him in 2000-01. Led the team to its first NHL playoff appearance and series win with a Game 7 shutout (3-0) against Phoenix in 1997. The next same season he was named to the NHL All Star game. His eight-season run ended with a 173-202-52 record in 441 games. He was some Guy.

Swen Nater, UCLA basketball center (1971 to 1973):

From starting life as an orphan, to finding his parents on a TV show, going to Long Beach Wilson High to Cypress College, and then playing on two NCAA title teams as Bill Walton’s backup may have been enough for the 6-foot-11 Dutch national. But he moved on, as the ABA’s rookie of the year, leading that league in rebounds (1975 with San Antonio) and then in the NBA (1980 with San Diego). The Lakers, who originally drafted him in the first round of the 1973 NBA selection (No. 16 overall) despite the fact he never started a game at UCLA, finally signed him as a backup to Kareem Abdul-Jabbar in 1983-84 (wearing No. 41) and he got to the NBA Finals. At the 2004 NBA All-Star game, he was officially named “Mr. Clipper.” After retiring as a player, he would go on to help start the Christian Heritage athletic department and lead the men’s basketball team to a national title. He ended up as a highly sought-after motivational speaker and executive of a Fortune 500 company. Here he is discussing his current affairs.

Have you heard of these stories:

Joe Grahovac, Fullerton College basketball forward/center (2024-25):

It almost sounds like a cross between Brendon Fraser’s anxiety-riddled character in the Albert Brooks film “The Scout,” or another April Fool’s story about Sidd Finch. Both were fictional baseball stories. This real-life basketball story comes from almost the same roots. Leading the Fullerton College Hornets to the state title game, the 6-foot-10 big man with the bright orange curly hair and long beard emerged as the unlikely California Community College Athletic Association (CCCAA/3C2A) State player of the year in 2025. It has to be noted: That was his first full season of organized basketball, having quit at both Foothill and Tustin High and then learning the enjoyment of the sport through playing pickup games at a 24 Hour Fitness. That led to invitations to adult leagues, such as the Drew League in 2021, where he started to get attention. Grahovac at first enrolled at Vanguard University in Costa Mesa, but also left that program, disillusioned by the college experience. In his only season at Fullerton College, Grahovac, who was 23 by that time, averaged 15.9 points, 6.6 rebounds, 2.7 blocks, 2.2 assists and shot nearly 40 percent from 3-pont range. He had a career-high 32 points against Santa Ana College on Feb. 19 and six games of double-doubles, including four straight in late January. That earned him a scholarship to spend his sophomore year at St. Bonaventure, wearing No. 32 (could it be the next Bill Walton?). The connection came via the recruiting of Adrian Wojnarowski, the GM of his alma mater after retiring from ESPN as a basketball insider.

Gig Sims, UCLA center (1976-77 to 1979-80):

At 6-foot-9, 240-pounds and the agility to run the floor and block shots as the All-CIF Southern Section 3A Player of the Year at Redondo Beach Union High, Sims was one of Gene Bartow’s top recruits for his program in the post-John Wooden era. As mentioned in his bio for the inaugural class of the Redondo Beach Athletic Hall of Fame in 2013: An eample of the lanky Sims’ dominance was the championship game of the Pacific Shores Tournament in 1975, lifting the Sea Hawks to the title for the first time in 11 years by scoring 33 points, grabbing 16 rebounds and blocking eight shots. As it turned out, Sims played for three coaches in four seasons at UCLA as the team won three conference titles and, in his senior year, reached the championship game of the NCAA tournament before losing to Louisville. In 1980, he was drafted by the Portland Trail Blazers in the 10th round and after being cut, played professionally in Europe until 1989.

Jason Collins, Harvard-Westlake High School center (1994-95 to 1996-97):

Before he and his twin brother Jarron were All-Americans at Stanford, and before they went into each play more than 10 years NBA — and well before Jason became the first openly active gay athlete to play in any of the four major North American sports leagues in May of 2013 — he made a name for himself at this North Hollywood private school. The Collins led the program to the 1996 and 1997 CIF state Division III titles with a combined record of 123-10 in four seasons. Jason also broke the California career rebounding record with 1,500. The 6-foot-10 senior averaged 19.9 points and 12.1 rebounds for the 36-1 Wolverines, making 71 percent of his shots from the field. He ended his prep career with a 24-point, 17-rebound performance in the state final against Hillsdale. Jason was born eight minutes before Jarron, for the record, in Northridge in 1978. In a 2025 story for the New York Times, Jason Collins was interviewed about whether there was any progress in athletes coming out since he came out in a national essay for Sports Illustrated, followed up by a conversation with then-NBA commissioner David Stern: “They were extremely supportive. I couldn’t have done what I did without seeing what the leadership of the NBA was doing. When I first entered the NBA in 2001, players were allowed to use homophobic language without consequences. That changed in the mid-to-late 2000s. There started to be fines for using homophobic language. When I saw those fines being levied, especially with a minimum fine of $50,000 being implemented, that to me was a sign that NBA leadership has my back.”

Spencer Haywood, Los Angeles Lakers forward (1979-80):

The four-time NBA All Star, one-time ABA MVP, Basketball Hall of Famer and famous for challenging the league rule requiring players to be four years out of high school before they could turn pro landed with the Lakers for their 1980 title run under coach Paul Westhead. That season saw him appear in 76 games as a role player, but a cocaine addiction came up and he was dismissed by Westhead during the NBA Finals for falling asleep during a practice. Years later, Haywood admitted he hired a Detroit mobster to kill Westhead. “I left the Forum and drove off in my Rolls that night thinking one thought—that Westhead must die,” Haywood told People magazine. “In the heat of anger and the daze of coke, I phoned an old friend of mine, a genuine certified gangster… We sat down and figured it out. Westhead lived in Palos Verdes, and we got his street address. We would sabotage his car, mess with his brake lining.” Haywood’s mother dissuaded him from going through with the hit. These days, he wants the NBA to recognize the struggle from his court battle by proclaiming the outcome “the Spencer Haywood Rule.”

Michael Alo, Banning High fullback/linebacker/punter (1977 to 1980): The two-time CIF L.A. Section Player of the Year led the Pilots to a 14-0 record as a senior and was named California’s state Mr. Football as well as national player of the year recognition. In the 1980 Banning-Long Beach Poly contest at Veterans Stadium, Alo had a broken hand and did not suit up, but as his team trailed by two touchdowns at halftime, he convinced coach Chris Ferragamo to let him play with a padded brace, taking off the cast. Alo scored twice in the second half to lead Baning to a 14-13 win. “He was the best player I’ve ever coached,” said Ferragamo. “There wasn’t a finer football player and there wasn’t anything he couldn’t do on the field.” Alo went to USC on a scholarship but never played a down because of neck injury.

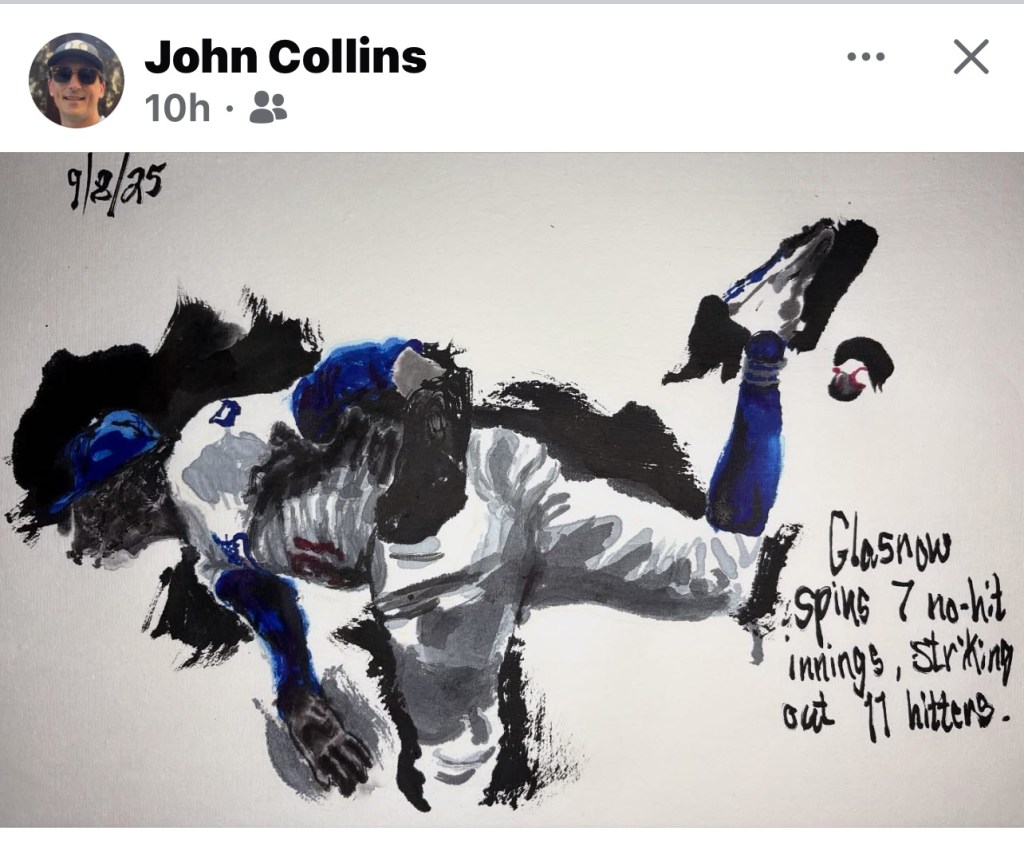

Tyler Glasnow, Los Angeles Dodgers pitcher (2024 to present): When the 6-foot-8 right-hander out of Hart High School in Santa Clarita made his way back to Southern California in a December, 2023 trade, Glasnow said he took No. 31 because, well, No. 20 (which he wore for years in Tampa Bay) had been retired (for Don Sutton), but it was also a chance to reconnect to his Little League and travel team jersey number. “I always wanted to be 31,” he said. “I was picking numbers and I was like, ‘This is perfect. I’m going back home and 31 is available.’ So I chose 31.”

We also have:

Ron Riley, USC basketball forward (1969 to 1972)

Brad Penny, Los Angeles Dodgers pitcher (2005 to 2008, also No. 30 in 2004)

Max Scherzer, Los Angeles Dodgers pitcher (2021)

Joc Pederson, Los Angeles Dodgers outfielder (2015 to 2020, also No. 65 in 2014):

Mel Counts, Los Angeles Lakers center (1966 to 1970, 1972 to 1974)

Zelmo Beaty, Los Angeles Lakers center (1974 to 1975)

Doug Rau, Los Angeles Dodgers pitcher (1972 to 1979)

Hoyt Wilhelm, Los Angeles Dodgers pitcher (1971 to 1972)

Dickie Thon, California Angels infielder (1979 to 1980)

Anyone else worth nominating?

1 thought on “No. 31: Cheryl Miller and Reggie Miller”