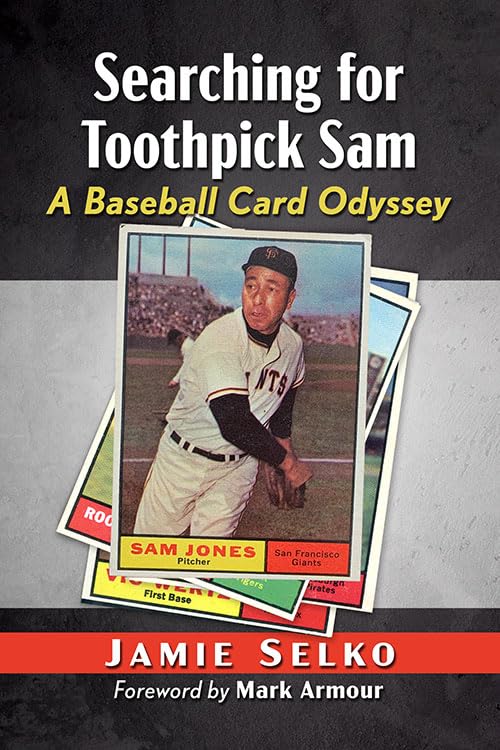

“Searching for Toothpick Sam: A Baseball Card Odyssey”

The author:

Jamie Selko

The publishing info:

McFarland

216 pages

$29.95; released Dec. 17, 2023

The links:

The publishers website

At Bookshop.org

At Target.com

At Powells.com; at BarnesAndNoble.com; at Amazon.com

“When Baseball Was Still Topps:

Portraits of the Game in 1959, Card by Card”

The author:

Phil Coffin

The publishing info:

McFarland

243 pages

$39.95; released December 5, 2023

The links:

The publishers website

At Bookshop.org

At Powells.com

At BarnesAndNoble.com; at Amazon.com

“Cramer’s Choice: Memoir of a

Baseball Card Collector Turned Manufacturer”

The author:

Mike Cramer

The publishing info:

McFarland

253 pages

$29.95; released Oct. 17, 2023

The links:

The publishers website; at Bookshop.org

At Powells.com

At BarnesAndNoble.com

At Amazon.com

The reviews in 90 feet or less

The stories stack up like a pile of baseball cards. The residual effects of the COVID-19 pandemic lock-down has resulted in, for some reason, baseball cards becoming a ring-a-ding thing again.

We had some time to go through, sort, re-evaluate, and find like-minded, lonely people who believed in this idea. In September of 2020, as we extended our annual baseball book review series, Axios sports examined the trading card boom over the prior months. As well as exposing the dark side of forgeries. In July, Bill Shea of The Athletic had a piece under the headline “State of the sports card boom: After sky-high surge, is the market still healthy?” The conclusion was: Yeah, kinda.

In September of 2022, The Wall Street Journal produced: “The Most In-Demand Investment Might Be Your Baseball Card Collection.” Then in March 2023, Ian Thomas of CNBC posted the real push moving this forward: “How Fanatics and MLB are planning to keep the trading card boom going.” Fanatics was the company that pried the rights to making MLB trading cards from Topps in August, 2021, ending a partnership that went back to 1952. Fanatics then acquired Topps outright in early 2023 for $500 million.

And if you’re wondering: The nine most valuable baseball cards in history are pretty much a) the ones you think they are and b) the ones you’ll never own.

Our personal cardboard collection during the pandemic wasn’t so much to revisit all the book binders, shoe boxes and plastic cases we’ve stashed away in various rooms and closets. It was renovating a home office that resulted in re configuring closet space — and actually gave the card collection a higher place of honor within the home structure. The space gained allowed us to display more book shelves. So binders with “Topps 1970-71,” and “Hall of Famers” and “Future Hall of Famers” (which was horribly in need of an update — sorry Chris Sabo) could be addressed.

Now there was also another shelf to hold our lineup of baseball card-related books:

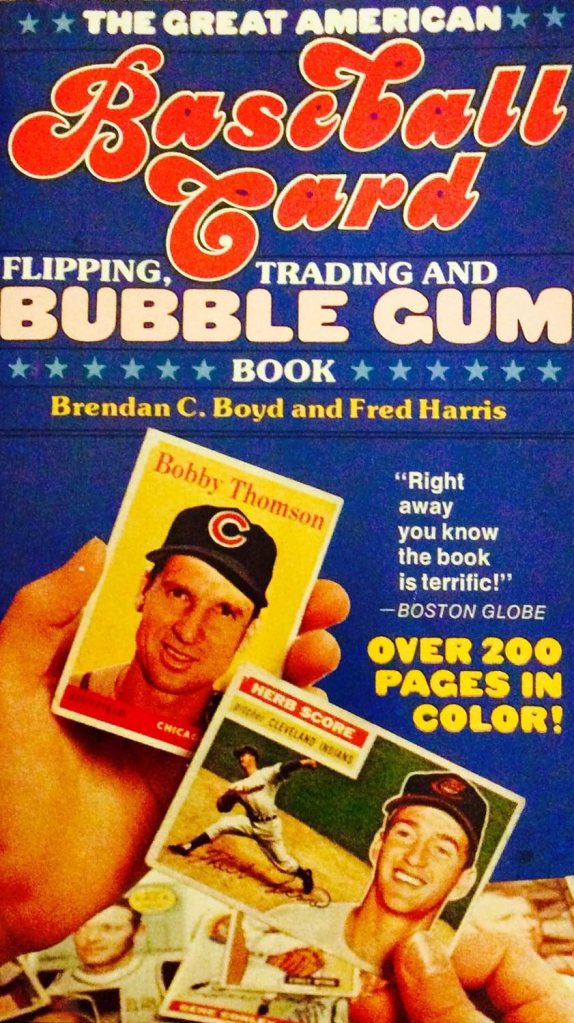

== “The Great American Baseball Card Flipping, Trading And Bubblegum Book,” by Brendan Boyd and Fred Harris (1973).

We saw recently how the e-book (right) is advertised as “The Spinal Tap of Baseball Books.” It’s still best described by people like Jeff Katz for the SABR Baseball Cards Research Committee: “For Hannukah that year I got (the book). It’s impossible to overstate the impact of this book on me, and every other card collector of the era, from 10 years old and up. Again, I’ll give it a shot. First, there were cards. Pages and pages of cards, nearly all from the 1950’s and 1960’s. I had never seen these before! How could I? The catalogs didn’t have many pictures, if they had them at all. What a gift. It made my head spin. Second, there was the writing. It was beyond funny: sharp, but warm, silly, but deep, nostalgic, but not maudlin. Harris and Boyd had a ‘60’s sense of irreverence and impudence, and even for a kid like me it resonated. There was a love for the game and the cards that was genuine, but not too serious. This was a life lesson I could take to heart. Third, there was a sense of shared community. Most of my friends were card collectors, but they were children. Harris and Boyd were grown men, seemingly in their late-20’s. They looked pretty cool too. What were these guys doing in the baseball card world? That looked like a future I could embrace.”

== “Cardboard Gods: An All-American Tale Told Through Baseball Cards,” by Josh Wilker (2010). We’ve come to realize how this really has influenced the way we review baseball books. What memories does this subject and title spark? How does this bring it forward? We are also inspired by the various covers this book has had with hardbound, softbound, and audio CD. Thanks Josh.

== “The Wax Pack: On the Open Road in Search of Baseball’s Afterlife,” by Brad Balukjian, arrived during that 2020 hunkering down, which we happily reviewed that April. The cover alone made our heart skip a beat.

== “Confessions of a Baseball Card Addict: The Story of a Man Who Acquired Ten Million Cards and Managed to Stay Married,” by Tanner Jones (2018).

== “Baseball and Bubble Gum: The 1952 Topps Collections,” by Tom and Ellen Zappala with John Molori. In our extended review we also touched on many other baseball card related things swirling in our head in September of 2020.

== “The Card: Collectors, Con Men and the True Story of History’s Most Desired Baseball Card,” by Michael O’Keefe and Teri Thompson (2007). Based on a true story, we believe.

== “Game Faces: Early Baseball Cards from the Library of Congress,” by Peter Devereaux, with a John Thorn forward. From Smithsonian Books, 2018. Just spectacular considering the institution behind it all. You’ll find the book shelved under “history.” And there was “Baseball Card Vandals: Over 200 Decent Jokes on Worth Cards,” by Beau and Bryan Abbott, from 2019.

We reviewed both “Game Faces” and “Vandals” on the same post in April 2019. We called it the “the best of baseball cards (and) the worst of baseball cards.” And loved them both.

“Vandals” is a reflection of the kid on your block who not only resented that you collected cards and protected them, but wanted to show you how much fun you were missing. As a result, you saved all your common cards, got a Sharpie, and joined in the Mad Magazine-type fun with them. Now look at the website for updated stuff. And you can actually purchase the artwork. Yes, it’s art. Not a surprise this thing hasn’t run out of material all these years later.

== “The Bubble Gum Card War: The Great Bowman & Topps Sets from 1948 to 1955” and “Before There Was Bubble Gum: Our Favorite Pre-World War I Baseball Cards,” both by Dean Hanley, self-published under the name of Mighty Casey Books, from 2012.

Sorry to bury the lead here for this review, under these pile of perilous paragraphs, but it now appears our closet shrine has three more additions.

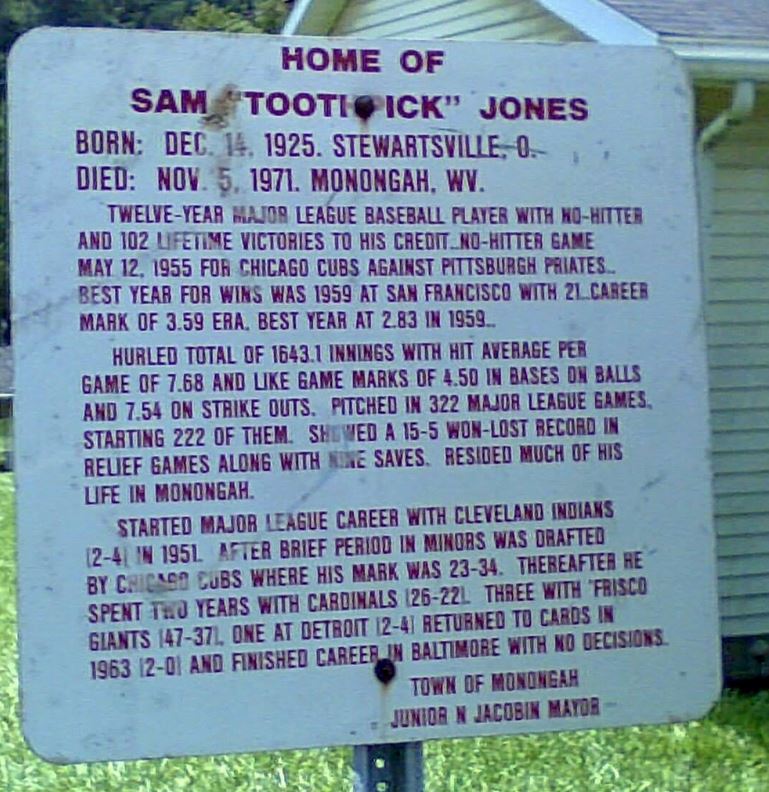

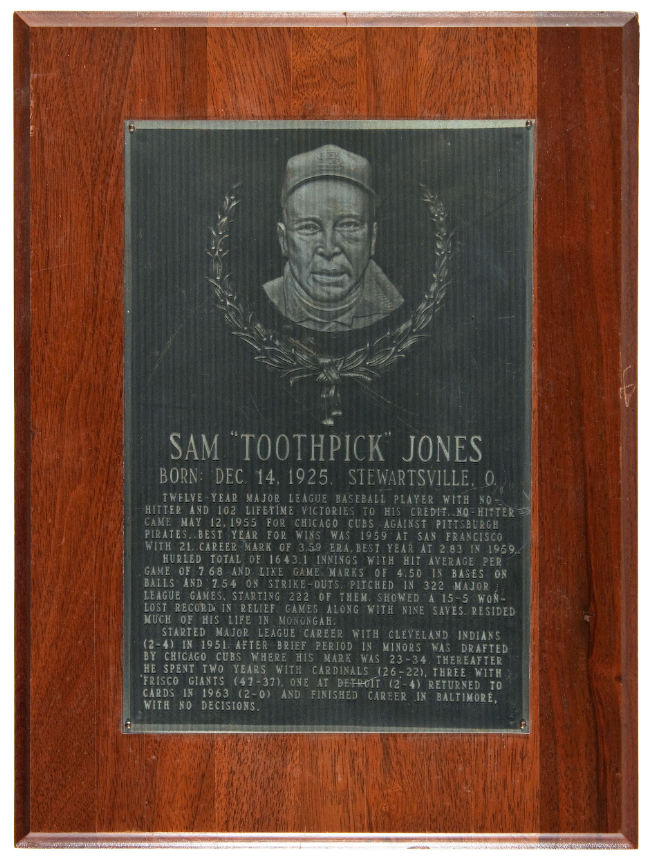

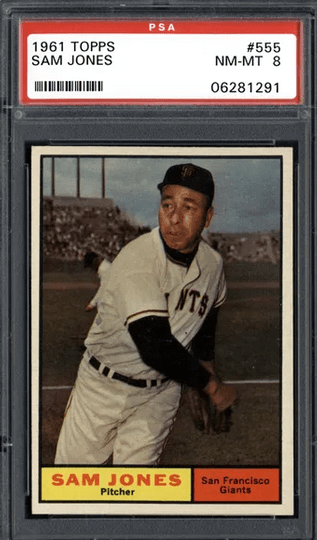

On the back of Sam “Toothpick” Jones’ 1961 Topps #555 baseball card, it says it is presenting the “Complete Major and Minor League Pitcher Record” of his career to date.

Perhaps.

For starters, it doesn’t mention his birth name was Daniel Pore Franklin, from Stewartsville, Ohio. His father, John, left the family in 1930. His mother, Athelstine Jones, remarried.

The illustrations at the bottom of the card boasts two important notes: He threw a no-hitter against Pittsburgh in 1955. He led the National League in strike outs for three seasons – that includes the 198 he had during that same ’55 Chicago Cubs campaign when he, ahem, also lost 20 games.

(Not pointed out: Jones was the first African-American to throw a no-hitter. Because many fans – and teammates – perhaps didn’t even realize he was Black. Jones struck out Dick Groat, Roberto Clemente and Frank Thomas on 11 pitches — Groat and Thomas looking — after walking the bases loaded in the ninth to preserve that 4-0 victory. He had seven walks in that game, including cleanup hitter Dale Long three times. Long was due up after Thomas whiffed in the ninth. Jones still only faced 31 batters for his 27 outs making 136 pitches.)

The card also starts his row of statistics at Wilkes-Barre in the Eastern League in 1950. Then to San Diego of the Pacific Coast League. In 1951, he made his debut with the Cleveland Indians — two games, nine innings, long enough to post a 0-1 record and 2.00 ERA.

We see Jones was also with the Indians for 14 games in ’52, but went back and forth to the American Association’s Indianapolis teams in ’52, ’53 and ’54. The Cubs had him in ’55 and ’56, then the Cardinals of St. Louis from ’57 and ’58.

But with the ’59 San Francisco Giants, Jones made a name for himself.

A National League-best 21 wins and a 2.83 ERA earned him a spot on the All Star team. He also had a league-best four shutouts – plus five saves. He was runner up to the Chicago White Sox’ Early Wynn in the Cy Young Award voting (when it was a combined honor for both leagues). Jones was also fifth in the NL MVP voting — ahead of teammate Willie Mays.

Jones followed that up with 18 wins in ’60 with the Giants. And that was his card. The point in his career with eight years of big-league play recorded.

But the record-keeping really wasn’t all there.

According to Baseball-Reference.com, Jones’ 14-year big-league career actually began with the Cleveland Buckeyes of the Negro Leagues in 1947 and ’48, mirroring the first two seasons of Jackie Robinson’s MLB career with the Dodgers in Brooklyn. Jones was a combined 1-3 at ages 21 and 22, with a 6.58 ERA in more than 44 innings. But even then, that’s incomplete.

His bio on Wikipedia adds that he was with the Negro League’s Oakland Larks in 1946. For two years after that, he with the Kansas City Royals’ touring team led by Satchel Paige.

In 1949, we see no official stats for him recorded. The Wikipedia page says he was in Panama, also playing semi-pro ball as the Negro Leagues were fading out.

The Cleveland Indians, which had already signed Larry Doby as the first A.L. Black player three months after Robinson’s Dodgers debut, also brought in Paige in ’48, as the team went to the World Series. Much of that is explained in the 2021 book “Our Team: The Epic Story of Four Men and the World Series that Changed Baseball,” by Luke Epplin (which we reviewed).

Paige, who we’re led to believe was in his early 40s at that point, advised Cleveland owner Bill Veeck he might want to rescue the career of Jones, then just 24. So at least on Jones’ baseball card, we see the cities he spent in the Cleveland’s Single-A and Triple-A clubs from ’50 to ’53, and two batters faced in his Sept.22, 1951 debut, it was thanks to Paige and Veeck.

When Jones made his first appearance in 1952, on May 3, it included 39-year-old Quincy Trouppe as his catcher, another Negro League veteran. They formed the first Black battery in American League history — the Dodgers’ Don Newcombe and Roy Campanella had been the National League’s first all-Black pitcher-catcher combo in 1949. There is also the case of 20-year-old pitcher George Stovey and 30-year-old catcher Moses Fleetwood Walker forming the first all-Black battery in pro baseball history with the 1887 Newark Little Giants of the International League.

The Baseball-Reference also shows that — beyond this ’61 Topps card — “Toothpick” Jones had an 8-8 season with the Giants, moved onto Detroit (’62), St. Louis (’63) and Baltimore (’64), and hung around for three more seasons with the Pittsburgh Pirates’ Triple-A Columbus Jets affiliate in ’65, ’66 and ’67. He became something of a mentor to a very young Doc Ellis, who was on that team along with Steve Blass, Woody Fryman, Wilbur Wood and Bob Moose. Jones exited the game at age 41.

Sam “Toothpick” Jones, once the feature story in Sports Illustrated for its 1960 baseball preview issue calling him “A Toothpick for the Pennant” with the Giants, died in 1971 from neck cancer at age 45.

So in as much as that this Jones Topps ’61 card says so much, it also says so little.

And in the way Jamie Selko speaks so little – aside from the book title — about trying to find an autographed version of that card for his collection, it also says a lot about how much more we can use the baseball card as a launching point to someone’s history instead of just capturing that moment in time.

Because once upon a time, Selko was a baseball card-collecting fanatic, a way to keep him connected to the world, as he explains. Selko does a marvelous job of telling his relatable story – especially in detail about how he navigated the world to not just get the entire ’61 Topps set, but also have every card autographed.

All except for Sam Jones. But that part really isn’t the point to all this.

Selko was 13 in 1961, living in military housing in Germany. His dad was a Brooklyn Dodgers fan.

“If I got a quarter, I headed right down to the P.X. (the post exchange), plunked it down and walked out the proud owner of 25 more baseball cards,” Selko writes on page 14. “They were not an investment like hog futures or land in Florida. Cards were my friends and a joy.”

The reader can tell that Selko, who did the 2007 book, “Minor League All-Star Teams, 1922-1962: Rosters, Statistics and Commentary” for McFarland, finds this cathartic to talk about what this collection, and any baseball card, made him feel as a lonely kid who wanted acceptance.

“Then I spiraled even deeper down the rabbit hole,” he admits. “Now, I am not completely divorced from reality, but I know that baseball cards and autographs (and autographed baseball cards) have absolutely no intrinsic value whatsoever and that none of these last dozen autographs came cheaply (for his 1961 set), but to me they were worth every widow’s mite and every single lepton.”

With that, he spends Chapter 2 listing EVERY single card of that 1961 Topps pack – describing the quality of the photograph, his impression of it, and then digging up what he believes to be that player’s best day of the ’61 season. The names go from Rip Repulski, Rocky Bridges, Gene Conley, Brooks Robinson, Pumpsie Green, Eli Gurba, Steve Bilko, Marty Keough … and Roger Maris.

For example:

Card #150, Willie Mays, headshot: If this is not the worst Willie Mays card, then I don’t want to see a worse one (compare this to his 1954 card). He looks just plain aggravated in this shot, like the photographer interrupted him on his way to an important meeting. He signed the first few cards I sent, but then stopped signing except at shows. (Of course, I didn’t know that and kept sending cards that came back signed by a secretary, thereby rendering some of my signed multi-player cards worthless, along with MVP and All-Star cards.)

And this original Los Angeles Angel:

Card #246, Bob Davis, head and shoulders shot. Taken in Yankee Stadium. “Eleanor, do you think that that nice young man might be the new youth pastor?” He passed away in 2001 at 68. Best game in the 1961 season: Instead of pitching in 1961, Bob went back to Yale, eventually winding up with a degree in clinical psychology.

Maury Wills, we learn, doesn’t even have a card in this set. For his collection, Selko got Wills to sign a Dodgers’ team card, No. 86, along with coaches Leo Durocher, Carrol Beringer, Clay Bryant and Art Becker.

Now we admit deeper how this book also resonates: 1961 was the year of my birth. This is like a roll call of those from that time capsule. If Selko lists something the players did on my date of birth, June 8, I’m at full attention.

Such as:

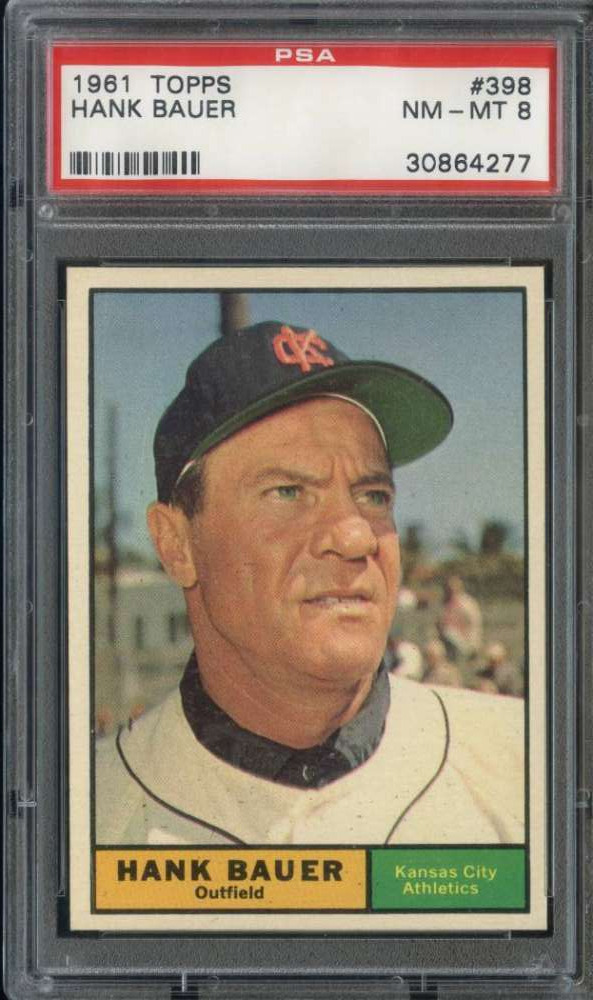

Card #398, Hank Bauer, headshot, Connie Mack Park in West Palm Beach. Make no mistake, this old dude could walk the walk. A Marine, he fought on Guam and Okinawa, earning two Bronze Stars and two Purple Hearts. (His brother, Herman, also a ballplayer, was killed in Normandy.) Mr. Bauer, who passed away in 2007 aged 84, always signed and returned every item I sent to him. Best game in the 1961 season: On June 8, he went 3–4 against his old Yankees team. He was named manager of the Athletics on June 19 and played in six more games after taking over the reins. In his last game as a player on July 21, he went 2–3 against the Tigers.

(From the box score: Bauer hit second and played left field in that June 8 game, the second of a double header).

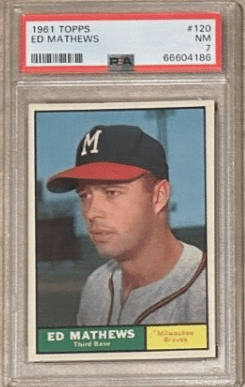

Card #120, Ed Mathews, headshot, taken in Connie Mack Stadium. This is the look of a young man secure in his place in baseball history (after nine years as a star in the majors, he was still only 29 years old, the second-fastest player to reach 200 home runs as well as the second-fastest to reach 300). What he didn’t know was that he would never again be the player after 30 that he was before it. Despite his Jimmie Foxx–like early and rapid decline, he is still rated the second-best third baseman of all time, and rightfully so. I honestly do not remember how many cards I sent to Mr. Mathews to sign before, because of bad luck with other major stars that started in the early 1980s, I started getting all my Hall of Famers’ cards signed either at shows or through their own sites. I’m pretty sure, however, that he was an SR: A (it means he had a signing rating grade of “A”) before I switched tactics on general principles. Mr. Mathews was 69 at the time of his demise in 2001.

Best games in the 1961 season: Eddie had a slew of big games in ’61. On September 23 he went 3–3 with three runs against the Cubs with two homers and four RBI, and 3–3 again on August 13 with one homer and three RBI. On June 8, he went 4–4 against the Reds with two homers, and on July 23 , he went 4–5 against the Pirates. There were other big games, but you get the picture.

There’s actually more context to that Matthews’ June 8 achievement. On that day, Mathews, Hank Aaron, Joe Adcock and Frank Thomas hit back-to-back-to-back-to-back homers against the Reds in the seventh inning at Crosley Field. It was the first time it ever happened in an MLB game. From the box score, the Reds still won the game, 10-8. Braves starting pitcher Warren Spahn also homered in the game.

So what else happened on June 8, 1961: “Toothpick” Sam started for the Giants at the 1 ½-old Candlestick Park against Philadelphia. He faced just eight batters, was charged with four runs (three earned), three hits and two walks. Solo homers by Willie Mays and Willie McCovey couldn’t save the Giants. Jones took the loss to drop to 5-5.

Selko points out that this “Toothpick Sam” card was part of what was called the “Topps Highs” that year — cards printed later in the season and numbered 522 through 589 to catch up with the early batch.

“Vaunted, fabled, storied, legendary myth-enshrouded,” as Selko writes about them on page 154.

At last, by page 162 we get to the heart of the matter. The title of the book. Selko writes:

Card #555, Sam Jones, follow-through in Candlestick Park. Arrrrrgh. I could have bought a signed #555 once for $50, back in 1984, but we didn’t have $50 to spare back then so I took a pass. I have neither seen nor heard of another since. Arrrrrgh. You are my White Whale, I am your Ahab. “To the last I grapple with thee; from hell’s heart I stab at thee.” Well, okay, perhaps that is a bit overstated. Of course, I bear no personal animus toward the departed “Toothpick” Sam, and I don’t believe that my life has been consumed in this damned chase, this folly, this search for my own personal Grail. But man … years before the mast, crawling through the desert towards Cibola and through the jungle for the Lost City of Z. And for naught, all for naught. I fear that I shall enter The Big Sleep Samless. As for his signing proclivities, I am not qualified to speak. He was quite young when he died (only 45 when he passed in 1971). I recommend that any interested reader check out Rory Costello’s biography of Sam Jones at the SABR bio site. Best game in the 1961 season: he lost 1–0 to the Braves on April 28, striking out 10 and suffering an unearned run.

Selko also records this fact in the footnotes: In ’84, Selko was “a lowely E-5 making $942 a month and we already had four kids.” That’s why he didn’t buy the card.

Selko’s other claim to fame: The Eugene, Oregon, resident won his fifth career team trivia title and second in a row at the SABR 49 convention. He and Bill Carle were also part of winning teams in 1985, 1986, and 1993 — the last time the SABR convention was held in San Diego.

So now Selko’s done this book, putting that information into the universe, it won’t seem so trivial.

************

Phil Coffin, meanwhile, an editor at The New York Times and member of the Society for American Baseball Research since 1994 living in New Jersey, takes the approach above in creating his “When Baseball Was Topps” look at the 1959 set.

The context is how he and his brothers were engaged in the Los Angeles Dodgers-Chicago White Sox World Series of ’59.

As Coffin explains as well in an interview with Sports Collectors Daily, this was all about doing essays about each of the 572 cards in the set, the first one he actively collected as a kid.

“It didn’t start out as a book,” he says. “Three years ago I wrote some baseball essays that were frivolous. Silly stuff. For Bastille Day, I wrote about guys named France or French. For Flag Day, I’d write about guys named Red, White or Blue. I wrote about the players in the Eddie Gaedel game (Aug. 19, 1951). I was doing these essays and sharing them. It was fun.”

Then came his re-engagement with the ’59 set.

“I was 6 and was falling in love with the game. The cards were a nickel a pack and you’d get six cards and a stick of unpalatable gum.

“I always loved the ’59 cards. But like a stoonad, I forgot how many cards were in the set. My wife kept telling me, ‘That’s a book,’ but I resisted. But along about a third of the way, I said she was right.”

And now we get to share.

Coffin, for example, writes about Card No. 20: Los Angeles Dodgers outfielder Duke Snider this way:

At the peak of his career, Duke Snider told Roger Kahn, as reported in The Boys of Summer, about his disillusionment with baseball: “If it wasn’t for the money,” Snider, then 26, told Kahn, “I’d just be as happy if I never played a game of ball again.” Ah, the money. Snider never made more than $44,000 in a season, far less than the contemporaries to whom he was often compared, Mickey Mantle ($100,000) and Willie Mays ($165,000). Snider told Kahn he had a dream of owning an avocado farm, and he did, but financial reversals forced him to sell it. Then in 1995, he pleaded guilty to not reporting more than $100,000 in income from sports memorabilia shows and was fined $5,000 in addition to having to pay nearly $30,000 in back taxes and more than $27,000 in interest and penalties, according to the New York Times. He pleaded guilty in Brooklyn, where he had earned his fame. “Because of who you are, you have been publicly disgraced and humiliated,” the judge said. “And it has taken place in Brooklyn, where you were idolized by a generation of which I was a part.” (Darryl Strawberry and Willie McCovey pleaded guilty to similar charges. Sluggers beware).

Heavy stuff for Snider to take to his grave in 2011 in Escondito, and have part of your New York Times obituary. The quote from Snider added to that obit: “We have choices to make in our lives. I made the wrong choice.”

Say it ain’t so, Duke.

The obit also points out: “Snider was chided by some sportswriters as being ungrateful for his good fortune when he collaborated with Kahn for a May 1956 article in Collier’s titled ‘I Play Baseball for Money — Not Fun’.”

So while we’ve still got Sam Jones fresh in our midst, here’s what Coffin writes about No. 75 in the ’59 collection about the then-St. Louis Cardinals pitcher:

“Every profile I have ever read of Sam Jones refers to the tooth pick that he was said to always have in his mouth. One of his nicknames was Toothpick Sam Jones. Sports Illustrated reported that his wife said he slept with a toothpick in his mouth. So why doesn’t his baseball card ever have a photo of him with a toothpick/ Not his card in 1952 (his rookie year). Nor in 1953, ’55, ’56, ’57, ’58, ’59, ’60, ’61, ’62 or ’63. (He apparently didn’t have a Topps card in 1954 or 1964). His other nickname was Sad Sam Jones (presumably because there was an earlier Sad Sam Jones who pitched from 1914 to 1935). Jones really did look sad on most of his cards.”

And, on the back of that ’59 card, the cartoon perpetuated the mystery.

Coffin added that the one odd card for him in this set — Russ Heman (No. 283), in an airbrushed Cleveland uniform for his rookie card. Coffin recalled that he had so many duplicates of Heman, it was hard to forget him.

“I got 20 of those,” he said … “one for every major league inning he pitched.”

In 1961, Heman ended up getting a call up to the Indians for six games. He got into another six games for the Los Angeles Angels. And that was it.

And now we feel we kinda know him, and Coffin, a little better now.

************

In “Cramer’s Choice,” Mike Cramer takes us on an entrepreneurial adventure we can’t say we saw coming.

He writes in the introduction that when he had a cancer diagnosis in 2020, he found out that his four children, a daughter-in-law and a granddaughter enjoyed hearing the stories of how he amassed this huge baseball card collection as a teenager.

Then he went off to the Bering Sea to join the rugged crab-fishing business with his uncle to make money in the summer so he could keep financing his habit and mail-order endeavor.

“Mike showed a lot of guts hiring on as deckhand on crab boats in Alaska,” uncle Kris Poulsen writes as a book blurb. “He knew there was good money to be had and he was not held back by adversity. His goal was his compass: he used that money to start his own trading card company. That showed a lot of guts, too.”

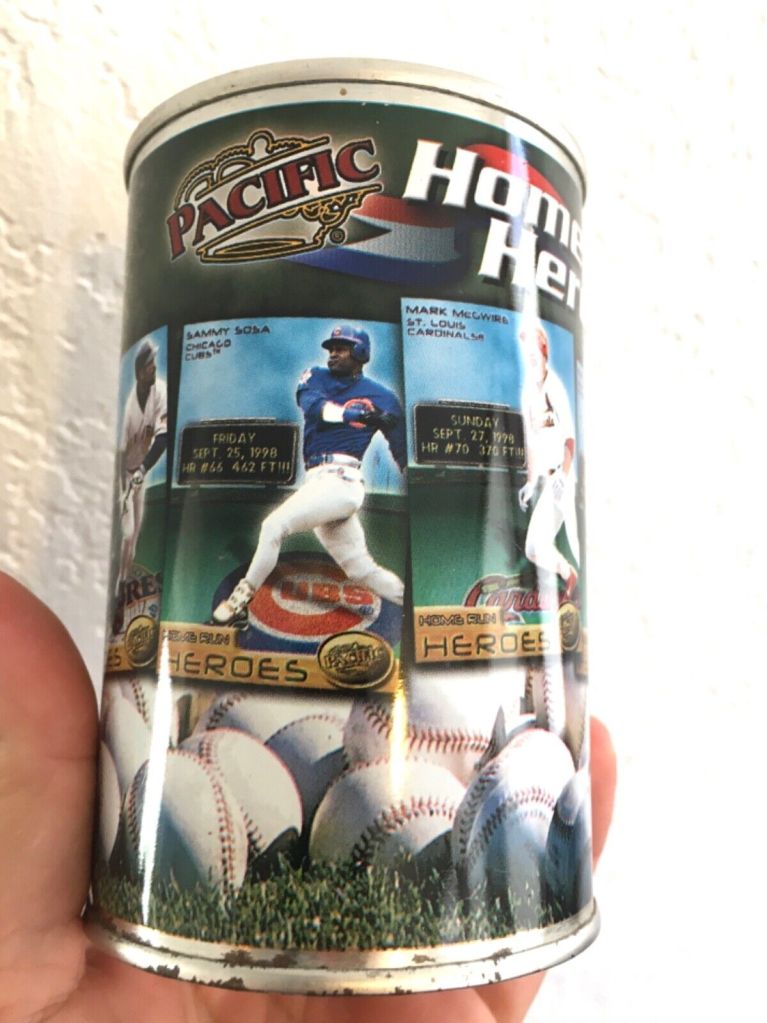

That led to launching his own fan-friendly Pacific Trading Card business (named after the way he got his start-up cash), spanning 1980 to 2004.

His family inspired him to write the book.

The first card he can remember having: A 1960 Fleer All-Time Greats card of Babe Ruth. Not the one on the left. See below.

“I put that card in my back pocked and must have taken it out a hundred times to look at on my walk home,” he writes. And the page includes an updated photo of that card. Here’s what PSACard.com says about that particular card value.

Along the way, we find out things like how a DF-Packing machine works to wax wrap baseball cards.

And how a Tom Brady Pacific rookie card he created ended up selling for $117,000 in 2021.

And by the time he sold the company, he started a new hobby collecting antique military helmets, medals, swords, paintings and guns. And he sold off all his baseball cards – except his Pacific Trading Cards.

Here’s more on the Pacific history.

“My Pacific cards were stored away on the shelves in my library for nearly 20 years before I began to look at them again,” he writes on page 213. “I am still amazed by the quality and creativity or our cards. (I confess, I have thought this before …)” And his cards have lived on.

How they go in the scorebook

Valued possessions. Great memories. Better testament to the nostalgic power of cardboard.

It’s all in the cards.

Even if they were once stuffed into a can and sold like a magician’s magic trick of fake peanuts.

Just to see if people would buy them.

I would have had I known. And still kept it closeted.

But if I ever wanted to sell them … Apparently it can be habit forming.

You can look it up: More to ponder

== These shirts are for sale at Homage.com for $32:

== Want a Mike Cramer bobblehead. It can be had.

== A review of “Cramer’s Choice” by SportsCollectorsDaily.com writer Jeff Morris from 2023.

1 thought on “Day 11 of 2024 baseball book reviews: We’re all card-carrying members”