This is the latest post for an ongoing media project — SoCal Sports History 101: The Prime Numbers from 00 to 99 that Uniformly, Uniquely and Unapologetically Reveal The Narrative of Our Region’s Athletic Heritage. Pick a number and highlight an athlete — person, place or thing — most obviously connected to it by fame and fortune, someone who isn’t so obvious, and then take a deeper dive into the most interesting story tied to it. It’s a combination of star power, achievement, longevity, notoriety, and, above all, what makes that athlete so Southern California. Quirkiness and notoriety factor in. And it should open itself to more discussion and debate — which is what sports is best at doing.

The most obvious choices for No. 21:

= Michael Cooper: Los Angeles Lakers

= LenDale White: USC football

= Eddie Meador: Los Angeles Rams

= Wally Joyner: California/Anaheim Angels

= Maurice Jones-Drew: UCLA football

= Jim Hardy: USC football and Los Angeles Rams

The not-so-obvious choices for No. 21:

= Alyssa Thompson: Angel City FC

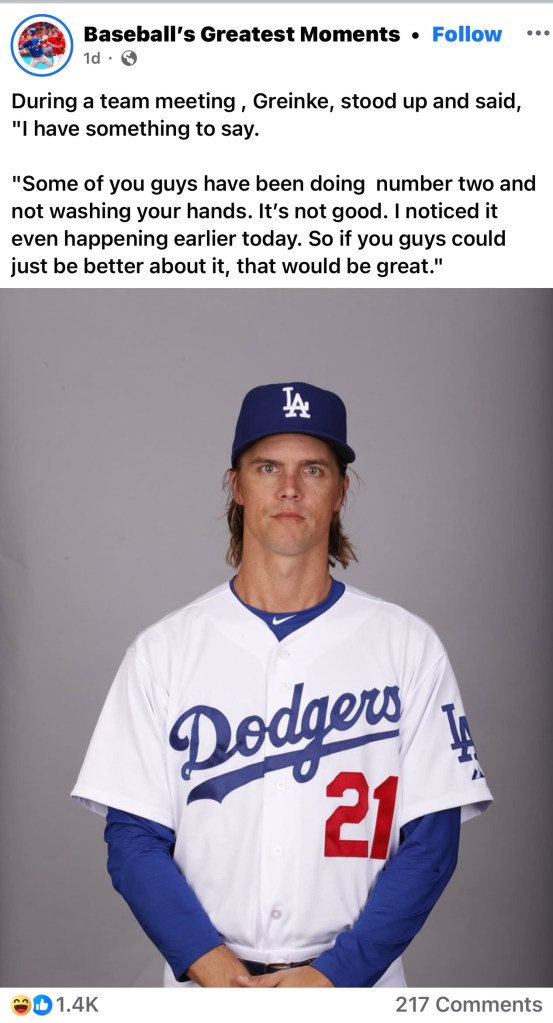

= Zack Greinke: Los Angeles Dodgers

= Walker Buehler: Los Angeles Dodgers

= Milton Bradley: Los Angeles Dodger

The most interesting stories for No. 21:

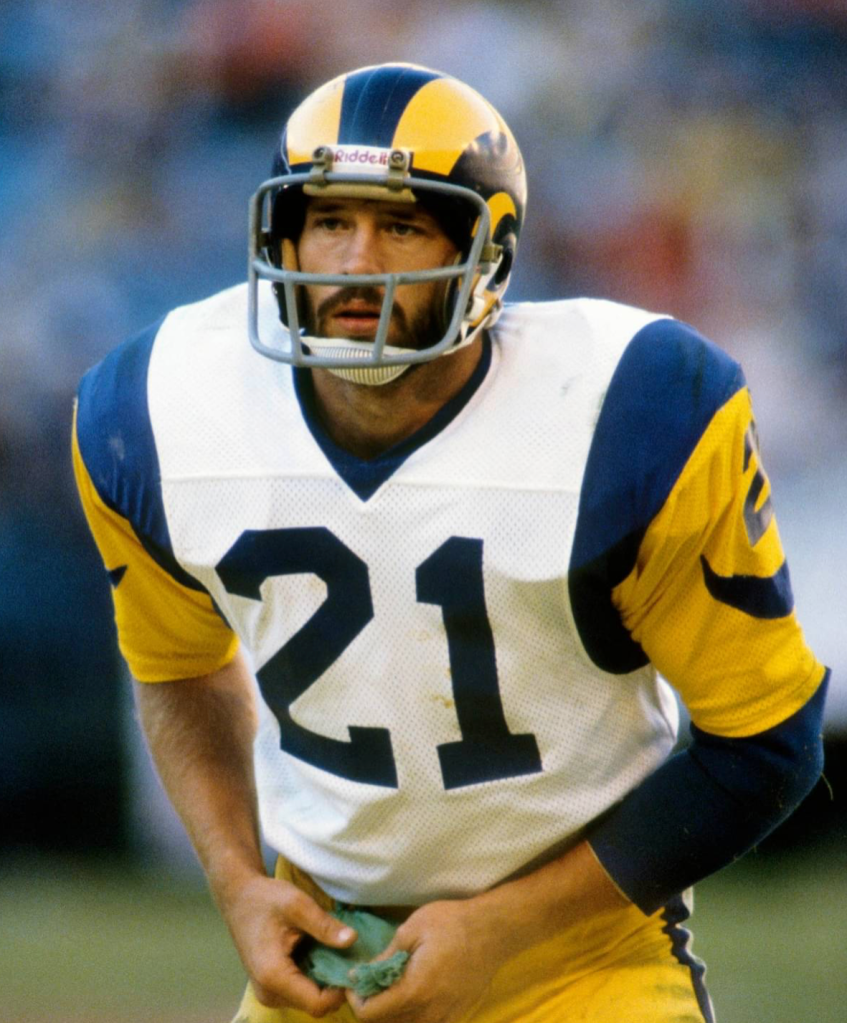

Eddie Meador: Los Angeles Rams cornerback/free safety (1959 to 1970)

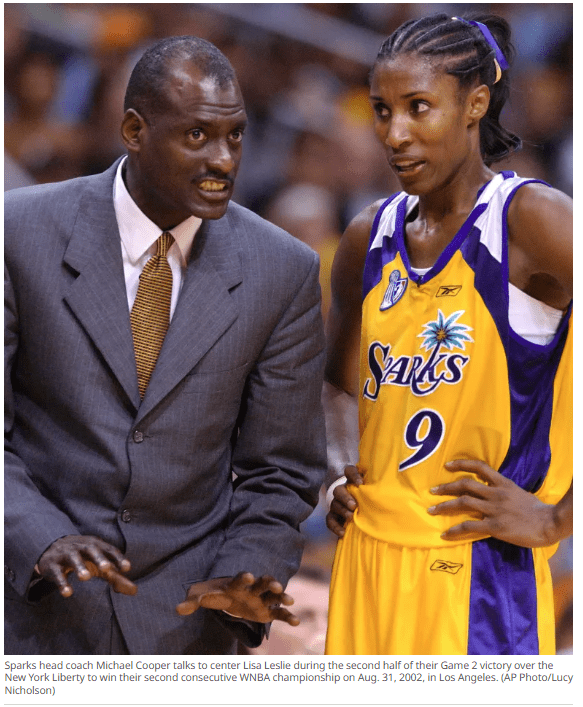

Michael Cooper: Los Angeles Lakers guard (1978-79 to 1989-90)

Southern California map pinpoints:

Los Angeles (Coliseum, Staples Center), Inglewood (Forum), Pasadena

Defend an argument that makes a case for Eddie Meador and Michael Cooper as members of their respective Hall of Fames.

The logic that rolls around in your brain can be like sitting at a blackjack table trying to find a pathway to 21.

Those who knows the stories of Meador with the Los Angeles Rams’ Eddie Meador and with Cooper and the Los Angeles Lakers’ Michael Cooper — two defensive specialists in their craft — might get too defensive when making their cases.

Meador has been in the Pro Football Hall of Fame discussion in more recent years than when he finished 12 seasons with the Rams in 1970, a standout on a team known year after year for its defensive prowess. He has made the Senior Blue-Ribbon Committee initial list for the Class of ’24 and ’25, survived a few cutdowns, but never made it to the final ballot. In October of 2025 he was again on the first-look list of 52 players too be considered for the Hall of Fame’s Class of 2026. Meador is among eight defensive backs, making it even more difficult to break free from the crowd.

Cooper, the spindly small forward/shooting guard who stood 6-foot-7 and may have weighed 175 pounds, also played all 12 of his pro seasons in L.A. As a Laker during its Showtime Era, he was matched up specifically against the opponent’s most dangerous offensive player — Boston’s Larry Bird, Chicago’s Michael Jordan, San Antonio’s George Gervin. The role Cooper filled on that Laker dynasty rewarded him to be included in the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame’s Class of 2024.

Sometimes the cards come up in your favor. Maybe they don’t, so you keep playing new strategies, arguing with your sense of reason.

Double down, push your chips to the middle, and see what comes up.

A website existed under the domain EdMeador21.com with a homepage that read:

Welcome to the Pro Football Hall of Fame Nomination site for Eddie Meador: Leader, Hero, Father, Athlete, Champion, Legend. Also an endorsement quote from former teammate Merlin Olsen.

Meador’s son, Dave, was behind the Internet campaign.

“The voters don’t remember watching him play,” Dave Meador said on a podcast just a couple of months before his father’s September of 2023 passing. “And even if they were football fans, they weren’t necessarily watching the Rams or number 21 on the Rams at the age of 13, 10 or whatever. I think that’s a little bit of a barrier. Out of sight; out of mind.

“We are blessed to have had Dad with us all these years. We are proud of his football career, no doubt. But we are prouder of the man he was to us and to so many.”

Going back to 2009, Meador’s lack of Hall induction was questioned.

From Bleacher Report: “It is astonishing that Meador has yet to be inducted into Canton. He has gone to the same amount of Pro Bowls as 15 other defensive backs that are already inducted. … Tackles were not a recorded statistic in his era, but he exceeded 100 tackles in several seasons. He once had 126 tackles in a 14-game season, which is an impressive rate for a free safety. He was fast, quick, tough, and smart. For all he did on the field, he did even more off the field. He was very active in charities, especially with the Special Olympics. His leadership abilities were seen from his days in college up until the day he retired from the NFL.”

A six-time Pro Bowl selection. Two-time first-team All NFL. One of three safeties named to the NFL’s 1960s All Decade team — St. Louis Cardinals’ Larry Wilson and Green Bay Packers’ Willie Wood, the other two, are both enshrined at Canton, Ohio.

Meador still holds the franchise records for interceptions (46, five returned for TDs), blocked kicks (10), fumble recoveries (18 from the opp0nents, plus four more of his own teammates). Names to the Rams All-Time franchise teams when votes took place in 1970 and 1985.

They called him “The Gremlin,” for his relentless play.

“I probably was as good a ballplayer as some of the people that’s already in there,” Meador told the Los Angeles Times in 2009 from his home in Natural Bridge, Va. “Maybe not, but I think that.”

The Rams got him as a relative bargain, the 80th overall pick in the seventh round of the 1959 NFL draft. The team’s 10th player chosen at that point. (The Rams later in Round 28 also took Rafer Johnson out of UCLA, No. 333 overall). Only one Pro Football Hall of Famer came out of that draft — cornerback Dick LeBeau, out of Ohio State, taken by Cleveland in the fifth round.

Meador was simply an athlete — tailback, defensive back and kick returner for tiny Arkansas Tech.

The pivot point in Meador’s time with the Rams came when head coach Harland Svare moved him from left cornerback to free safety.

Eventually, new defensive-minded head coach George Allen saw Meador, at the height of the Rams’ “Fearsome Foursome” days, as the one who the most fearless. Meador called the Rams’ defensive signals. During a run where he was named to five straight Pro Bowls from ’63 to ’68, he collected 24 interceptions and returned two for touchdowns.

Then-Rams assistant Jack Faulkner once told a reporter that the fresh-faced rookie Meador “looks like Mickey Rooney but hits like Jim Brown.”

Meador also became a valued punt and kickoff returner. He even was the holder on the field-goal unit.

Meador once explained how his versatility gave him an advantage during in a key win against the Philadelphia Eagles in 1969. Before he intercepted a Norm Snead pass and returned it 34 yards for a touchdown, he was the holder at a point when the Rams lined up for a field goal trying to erase a 10-0 deficit.

“I looked over at the linebacker on the other side,” Meador recalled, “and I said to myself, ‘I’m going to take this ball and run it.’ I about killed (kicker Bruce) Gossett when he came running in to kick it. By the time he got to me, I was up and taking off.”

For the last two years of his career, he was president of the NFL Players Association.

The Rams staged an Eddie Meador Day in 2018 at the Los Angeles Coliseum, where they played for a short while after moving back from St. Louis as their current home in Inglewood was being built. Meador stood in the end zone on the field he played on, waving to thousands of Rams fans and they chanted his name.

“If the Hall of Fame doesn’t happen in his lifetime or doesn’t ever happen, the L.A. Rams gave him a Hall of Fame moment,” said Vicki.

In a 2023 Meador obituary written for the Los Angeles Times, Meador’s daughter Vicki forwarded a photo of her dad wearing the Rams’ No. 21 jersey and his trademark Brill Cream hair cut.

A letter to the editor in the Times appeared days after the Meador’s obit from Richard Whorton of Studio City that included:

“I was a 12-year-old kid working as a water boy at Rams camp during the summer of ‘59 in Redlands. While being ignored by most of the veterans, one rookie was always cordial and went out of his way to make me feel like I was part of the team. It was Meador, who ended up being one of the greatest defensive backs in Rams history. He not only should be in the Hall of Fame, but if the Rams did the right thing they’d retire his No. 21!”

Another letter was posted from reader Rick Magnante of Encino:

“Growing up in Los Angeles in the ‘50s and seeing my first professional football game at the Coliseum, I won’t forget those stars, the likes of Norm Van Brocklin, Elroy Hirsch, Jon Arnett, Les Richter and, of course, the undersized but truly appreciated Meador. In today’s game, the art of open-field tackling is a thing of the past. Meador stood out as singularly the best to date that I’ve ever seen. The fact that he is not in the Hall of Fame is hard to fathom. His career and numbers stand the test of time. Today they give out inductions like Schrafft’s mints. Please give Eddie the respect and recognition he deserves.”

In 1974, Michael Cooper and his Pasadena High team was featured in KNBC-Channel 4 High School Game of the Week against El Rancho.

Cooper’s grandmother, who had glaucoma and couldn’t see the TV screen well, wondered if there was a way for him to stand out from the rest of the players on his team, making it easier for her to spot him. Cooper wore high white socks, two sweat bands on his wrist and left his white tie strings hang out of his shorts.

“I looked different,” Cooper recalled. “And I had the game of my life. I had 24 points, 15 rebounds, three dunks and like four or five blocks. That was going to be my attire from there on out. Whether I was with the Lakers or anybody, I was gonna wear long white socks, two sweatbands and my strings out.”

Wearing No. 42, Cooper credited high school coach George Terzian for teaching him the fundamentals, particularly playing defense with feet positioning instead of reaching with arms and hands.

After two seasons at Pasadena City College, Cooper transferred to the University of New Mexico for his junior and senior seasons and became the Lakers’ third-round pick in the 1978 NBA Draft, 60th overall.

This was before Jerry Buss’ ownership, or the arrival of Magic Johnson selection. It was a piece of the “Showtime Era” that would reveal itself later with fans chanting “Cooop,” and Chick Hearn punctuating a dunk with a “Coop-A-Loop” declaration.

Larry Bird deemed Cooper “the best defensive player who ever guarded me … I’ll take that to my grave with me.” Cooper said he developed that mindset early when Jerry West was the Lakers’ head coach at time time he joined the roster.

“I’m heading to training camp. I get to Loyola Marymount, and when I walk into the gym I see Kareem Abdul-Jabbar and Jamaal Wilkes and Norm Nixon. So, we get into practice and stuff. Jerry pulls me to the side and he goes, ‘Coop, I already have scorers. I got 30 points in Kareem. I got 27 to 28 from Jamaal Wilkes. I got 22 to 25 in Norm Nixon. There is not enough balls to go around for you to get shots. So, I need somebody to play defense.’

“So, I said, ‘Hey, I already got the fundamentals down. I got the aggressiveness down.’ And now I’ve been told that this was going to be my role. So, I took that to heart, embraced it, got better and better.”

Picked on the NBA’s All-Defensive team first team eight times and second team three times, Cooper was able to hoist the title of 1986-87 Defensive Player of the Year as the Lakers outlasted the Celtics in six games for the NBA title. Cooper’s most memorable offensive performance came in Game 2 of the 1987 Finals, when he drained a then-playoff record six 3-pointers and finished with 21 points and nine assists to give the Lakers a 2-0 series lead.

For the most part, Cooper came off the bench even as many remember him on the court for the bulk of the game’s minutes. Of 872 games played for the Lakers, only 94 were as a starter. But that was all part of the Lakers’ entertainment presentation. It allowed for him to be singled out with the chants of “Coooop” when he reported in from the scorers table and give the game some extra energy when needed.

The most games he started in a season was 20 of 82 games in the 1984-85 campaign. The NBA’s Sixth Man Award was established for the 1982-83 season. The best Cooper ever finished in the voting was his Defensive Player of the Year campaign in ’86-87 when he was off the bench for all but two of his 82 regular season games.

Following his playing career, Cooper served as a special assistant to Lakers general manager Jerry West for three years, joined the Lakers coaching staff for four seasons (1994-97) under Magic Johnson and Del Harris. As a head coach for eight season with the WNBA’s Los Angeles Sparks, he started as the league’s coach of the year in 2000. The team won two league titles (2001 and ’02) and one runner-up (2003) with a record of 178-88 (.699) in the regular season and 26-16 (.619) in the post season. He also had a four-year run as the USC women’s basketball coach (2009-13) with a record of 72-57 (.558). Currently, he serves as the head coach for Cal State L.A.

Cooper remains the only person to win a championship as a player or coach in the NBA, WNBA and NBA Developmeal League (the later with the Albuquerque Thunderbirds in 2006).

In a Los Angeles Time story headlined “Why Michael Cooper finally made it to Springfield,” the conclusion is that it was a long time coming as he became an overlooked but well-deserving candidate. The Basketball Hall has always been a reflection of a player’s entire career in the game — from high school to college to professional, to Olympics and international play, to contributing as a coach and executive. Cooper’s resume checks off several boxes.

Magic Johnson had become one of Cooper’s greatest allies in this process of vetting and discernment by a block of voters who the public doesn’t really know as much about. The same goes for the voters of the Pro Football Hall of Fame and Hockey Hall of Fame.

It will be noted Cooper is now one of 14 Hall of Famers who averaged fewer than 10 points (along with players like Dennis Rodman, Ben Wallace and Dikembe Mutombo. Cooper’s greatest offensive season was 11.9 points in ’81-82 season. But Rodman, Wallace and Mutombo were also named to NBA All Star teams. Cooper never had that.

Cooper said West once told him that you have to have at least been a former All-Star and All-NBA player to get your jersey retired with the Lakers. That didn’t happen. But with the Hall of Fame induction, the Lakers plan to retire Cooper’s No. 21 on Jan. 13, 2025 at Crypto.com Arena, joining Johnson, Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, Jerry West, Elgin Baylor, Kobe Bryant, Jamaal Wilkes, Wilt Chamberlain, Pau Gasol, Gail Goodrich, Shaquille O’Neal, James Worthy and George Mikan.

“When I sit there and they asked me to pull that rope, and I can finally see No. 21 up there in the rafters with everybody else, it’s going to be a moment because, if you know, dying is part of living. And one day we’re all going to leave this earth,” said Cooper. “But the one thing that I get the opportunity to leave for my grandkids, my great grandkids — even with the advancement of these arenas changing, and pretty soon the Lakers will have to get a bigger place and all that — but you know what, whenever they change this arena, they have to put that jersey up there. And my grandkids will be able to say, ‘You know what, that’s my grandfather up there.’ ”

Who else wore No. 21 in SoCal sports history?

Make a case for:

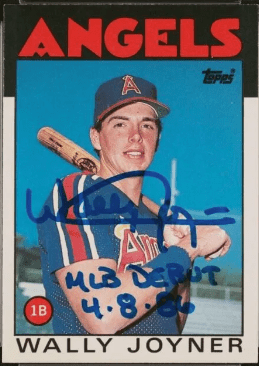

Wally Joyner, California Angels/Anaheim Angels first baseman (1986 to 1991, 2001):

The “Wallyworld” experience just blocks away from Disneyland during the late 1980s was something to behold. The baby-faced Mormon out of BYU came out of nowhere and was named to the AL All-Star team as a 24-year-old rookie — in the first two months of his big league career, he led the majors in homers. The Angels were just hoping he would be a suitable replacement for Rod Carew.

Joyner would finish with 22 HRs, 100 RBIs and a .290 batting average and runner-up to Jose Canseco (33 HRs, 117 RBIs, 15 SB) in the AL Rookie of the Year voting. If it makes a difference, Joyner finished eighth in the 1986 AL MVP voting; Canseco was 20th. That was also the only All-Star Game selection season Joyner would have in 16 MLB campaigns, ending back with the Angels in 2001 at age 39.

As Will Leitch once wrote about him: “If you were a kid in rural Illinois who collected baseball cards, suddenly no one was more important than Joyner. This was a player no one knew who was suddenly the most popular player in the sport. Getting his rookie card was like the Shroud of Turin, the briefcase in “Pulp Fiction” or the Maltese Falcon. Nobody cared about Jackson, Cal Ripken Jr. or Mike Schmidt. Joyner was all that mattered.”

In his second season, Joyner had a 34-homer, 117 RBI season and .285 average, with a career-best 4.1 WAR. But after six seasons, Joyner left, accepting a one-year, $4.2 million free agent deal with Kansas City — he stayed a Royal until they traded him after the ’95 season — instead of a four-year, $15.75 million deal from the Angels.

He didn’t want to leave.

“Wally Joyner stood at the press room podium at baseball’s winter meetings with tears in his eyes, unable to speak,” the L.A. Times’ Ross Newhan wrote in December, 1991. “The pressure of two months of futile negotiations, of a decision he never expected to have to make after six years with the Angels, was seeping out in an unexpected display of emotion. No one cries at leaving a last-place team, but … Wally Joyner did. Call that a crying shame.”

He came back as a free agent in 2001 and took No. 5 since pitcher Shigetoshi Hasegawa had No. 21, but was released half-way into the season. The thrill was gone.

Jim Hardy, USC football quarterback / defensive back (1942 to 1944), Los Angeles Rams quarterback (1946 to 1948):

The Fairfax High standout who started going to Trojans games in 1931 at age 8 became the MVP of the 1945 Rose Bowl, throwing two touchdown passes and running for another in a 25-0 win over Tennessee despite battling a 101 fever the night before. Hardy also dropped three key punts for USC that landed on the Tennessee 5, 8 and 7 yard lines in succession. In Hardy’s senior season, he set USC passing records with 58 completions, 739 yards passing and 10 touchdowns. That came a year after he threw three touchdown passes in the Trojans’ 29-0 win over Washington in the ’44 Rose Bowl. He also had 13 career interceptions as a defensive back. He made it into the USC Athletic Hall of Fame in 1999 and the Rose Bowl Hall of Fame in 1994. Hardy, who also played third base for USC’s baseball team from 1944 to ’46, ended up with the Rams during their first three years in L.A. after a stint in the Navy. He became the general manager of the Los Angeles Coliseum from 1973 to 1986, which included the 1984 Summer Olympics. He was noted to be the “oldest living” USC and Rams player when he died at age 96 in 2019.

Maurice Jones-Drew, UCLA football running back (2003 to 2005):

Before coming to Westwood, the generously sized 5-foot-7 running back made himself known to Southern California football fans when he, as a high school junior, scored four touchdowns for Concord De La Salle in a 29-15 win over Long Beach Poly in 2001. During a career at UCLA — he led the team in rushing all three years, set a school record in all-purpose yards (4,688), rushing yards from scrimmage (3,322), touchdowns (33), and an NCAA record of 28.5 yards per punt return — he also made a name for himself in changing his name. During his junior (and final) year of 2005, he learned from Coach Karl Dorrell that his grandfather, Maurice Jones, died of a heart attack while at the Rose Bowl to see the UCLA-Rice game. Drew, who took the last name of his maternal mother but was raised by his maternal grandparents, had his name legally changed to Jones-Drew, and in the NFL was most often referred to as “MJD.” He was named to the UCLA Athletic Hall of Fame in 2017 — not overlooking the fact he set the school’s single-game rushing mark with 322 yards and five touchdowns against Washington in his sophomore year.

LenDale White, USC football running back (2003 to 2005):

Fifty-two rushing touchdowns in three seasons established a Trojan career record as the “Thunder” to Reggie Bush’s “Lightning” combination during the team’s span of national dominance. He ran for three TDs in USC’s 55-19 win over Oklahoma in the 2005 Orange Bowl, and a year later, he had three more TDs as USC lost to Texas 41-38 in the 2006 Rose Bowl. In that game, with 2:13 left in regulation and USC holding a 38-33 lead, the Trojans were at Texas’ 45-yard line and needed two yards on fourth down to keep possession and run out the clock. Everyone knew the handoff would be to White. It was. He came up a yard short. Texas got the ball and won the game. “There’s nothing I can do to shake that,” said White, who finished his USC career with a powerful 3,159 yards, averaging 5.8 yards a carry. “He was kind of a free spirit, marched to his own drum,” quarterback Matt Leinart once said of him. “But I’ll tell you what, man, when the lights turned on, that dude was one of the best football players I’ve ever played with. He was one of the best teammates I’ve ever played with.”

Walker Buehler, Los Angeles Dodgers pitcher (2018 to 2024):

Anyone remember what number he wore in his MLB debut? Anyone … anyone? He was No. 64 in eight appearances for the 2017 Dodgers — because both Yu Darvish and Trayce Thompson had been sharing dibs on No. 21. A rebranded Buehler came back in ’18 and finished third in the NL Rookie of the Year voting with an 8-5 record, 2.62 ERA and striking out 151 in 137 innings. A two-time NL All Star (’19 and ’21), he missed the entire 2023 season with second Tommy John surgery. His ’24 regular-season season didn’t show he was all that ready to come back — a 1-6 mark with a 5.38 ERA. But then came the post-season. In the NLDS against San Diego, Buehler was still very shaky: He gave up six runs in five innings of his only start, Game 3, and took the loss as the Dodgers fell behind two games to one and appeared doomed. Somehow, they recovered. In Game 3 of the NLCS against the New York Mets, Buehler started, but something interesting happened. After pitching from a full windup to the leadoff hitter, he settled into a stretch. With better body control and simplifying things, he threw four shutout innings, striking out six. By the time he was called on to face the New York Mets in Game 3 of the World Series — in all likelihood, if injuries to Dodgers starters such as Tyler Glasnow, Clayton Kershaw, Michael Grove hadn’t occurred, he’d likely not been on the post-season roster — Buehler tossed five shutout innings and got the win, which put the Dodgers up, three games to none. Now it’s three days later, Game 5, with the Dodgers’ bullpen exhausted but a chance to snatch a win, manager Dave Roberts asked Buehler to pitch the ninth inning at Yankee Stadium with the hopes of preserving a 7-6 victory, and no relievers left to use. Done. The victory celebration started after Buehler struck out the last two batters he faced. As he nailed down the save, Buehler joined a short list of eight players — since saves became an official stat in 1969 — who had both a win and a save in the same playoff series. As more than 50 players in Dodgers history have worn No. 21, Buehler was the latest as he went the free agent route to Boston for the start of the 2025 season.

Zack Greinke, Los Angeles Dodgers pitcher (2013 to 2015): A year after he vacationed as a free agent with the Angels in Anaheim, Greinke logged three standout seasons for the Dodgers as he curated a potential Hall of Fame career, creating a formative top of the pitching rotation with Clayton Kershaw that many compared to the days of Koufax and Drysdale. The eclectic and rather mysterious Greinke was a two-time All Star and posted a 51-15 record with a 2.30 ERA over that time, gaining Cy Young and MVP votes, plus a Silver Slugger and a two Gold Gloves. His six-year, $147 million deal reached the halfway point to where Greinke could opt out. He did, spurning the Dodgers’ new six-year, $160 million deal, and off he went to Arizona for six years and $206 million.

Alyssa Thompson, Angel City FC forward (2023 to 2025):

The Gatorade National Player of the Year as a sophomore in 2021 out of Harvard-Westlake School in Studio City (48 goals, 14 assists in 17 games) had been playing on semi-pro teams since age 13 against college-aged players and signed an NIL deal with Nike at age 17 (along with her sister, Gisele) before becoming the youngest player ever drafted into the NWSL. The No. 1 overall pick by hometown Angel City FC in January of ’23 came with Thompson signing a three-year deal. In April, 2023, the third-generation Angeleno debuted with the U.S. Women’s National team (wearing No. 17) in the FIFA Women’s World Cup in Australia. In September of 2025, Thompson agreed to a five-year contract with Chelsea of the Women’s Super League for a $1.65 million transfer fee,the greatest in women’s soccer history. Thompson was the club’s all-time scoring leader with 21 goals in all competitions. Thompson has three goals and three assists in 22 games with the national team.

Lynn Cain, USC football fullback (1975 to 1978): A heralded defensive back at L.A.’s Roosevelt High and then the California Community College State player of the Year in 1974 at East L.A. College, Cain arrived at USC to start at fullback blocking for tailback Charles White on the Trojans’ ’78 national championship team. After a seven-year NFL career (that included a stop with the Los Angeles Rams in 1985 wearing No. 31), he returned to coach at East L.A. College and L.A. Southwest College.

Nolan Cromwell, Los Angeles Rams defensive back / free safety (1977 to 1987): Seven years after Meador left the Rams, Cromwell, a converted quarterback from Kansas and Big 8 Offensive Player of the Year, took the number and ran off another 11 years with the team, becoming a Pro Bowl player four seasons in a row (1980 to ’83) and collecting 37 interceptions, returning four for touchdowns, and setting a franchise record 671 in return yards. He was also a standout on special teams as a holder who could run the fake field goal. Cromwell made it onto the NFL’s All-Decade Team for the 1980s.

Tony Gwinn, Long Beach Poly High basketball (1973 to 1976): The future Baseball Hall of Famer known as “Mr. Padre” from his career in San Diego had basketball on his radar as well. As a point guard on the Jackrabbits teams that went 30-1 his junior year and won the CIF-4A title before more than 10,000 spectators at the Long Beach Sports Arena, Gwynn’s team was considered the best in the state. They also went 23-7 his senior season and lost in the playoffs trying to repeat. Gwynn, All-CIF Southern Section second team, went on to be an All-Western Athletic Conference basketball and baseball player at San Diego State.

Steve Grady, USC football tailback (1966 to 1967): After distinguishing himself at L.A.’s Loyola High as a wingback and middle linebacker, where he ran for 2,097 yards and scored 217 points in 12 games as a senior on a CIF title team (wearing No. 36), the CIF State Player of the Year gravitated to Coach John McKay’s Trojans teams as the running back in between Heisman winners Mike Garrett and O.J. Simpson. He had a combined 519 yards and 1 TD in his career, with 108 yards coming in a win over Oregon as Simpson’s injury replacement. After a brief NFL stint, Grady returned to coach at Loyola High and was named its head coach in 1976, staying through 2004 with nearly 270 wins and CIF titles in 1990 and 2003. He was inducted into the CIF Southern Section Hall of Fame.

Tayshaun Prince, Dominguez High of Compton basketball (1996 to 1998): Mr. California Basketball as a senior won four CIF titles and back-to-back state titles. He became the SEC Player of the Year at Kentucky (2001), won an NBA title with Detroit (2004) and an Olympic gold medal for Team USA (2008). His No. 21 was retired by Dominguez High in 2023.

John Hadl, Los Angeles Rams quarterback (1973 to 1974): He put No. 21 on for two seasons between Eddie Meador and Nolan Cromwell — keeping the number he had for the 11 previous years with the San Diego Chargers — and was second in the MVP voting in ’73 when he led the team to a 12-2 mark and a Pro Bowl nomination. Hadl, also once a fabled quarterback at Kansas, was gone the next year to Green Bay. But Hadl would return to Los Angeles — as the coach of the United State Football League’s Express, as a mentor to rookie quarterback Steve Young.

Cliff Branch, Los Angeles Raiders receiver (1982 to 1985): The last four seasons of his 14-year NFL career, all with the Raiders, game him a platform to perform in L.A., where with the ’83 Super Bowl champs he had a 99-yard TD reception from Jim Plunkett during a win against the Redskins in Washington, D.C.

Shigetoshi Hasegawa, Anaheim Angels pitcher (1997 to 2001): What drove Shiggy to Anaheim was a 57-45 record and 3.33 ERA during six seasons in Nippon Pro Baseball. But as a 28-year-old middle reliever, he didn’t net nearly the attention other Japanese players who came to the U.S. received. By the time he left the MLB in 2005 after nine seasons, he had the most appearances by an Asian pitcher in the U.S. (517), far ahead of Hideo Nomo’s 323 in 12 seasons (with Koji Uehara currently second with 436 in nine seasons). Hasegawa is included in the book, “Hall of Name: Baseball’s Most Magnificent Monikers” by D.B. Firstman (2020) with the entry: “Four short yet lyrical syllables in the first name and four more int he last. The name looks daunting to pronounce but is actually reasonably easy once you hear it a couple of times. And speaking of hearing it, no less a public speaking authority than the late Yankees public address announcer Bob Sheppard deemed Hasegawa’s name as one of his favorites to say over the P.A. system.”

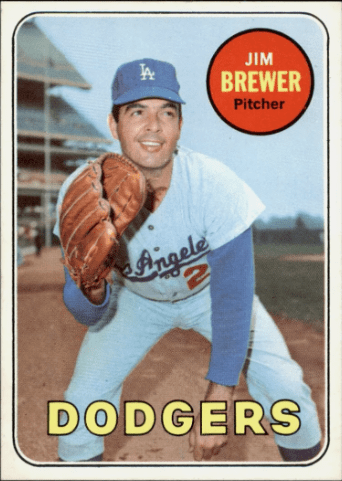

Jim Brewer, Los Angeles Dodgers pitcher (1964 to 1975), California Angels pitcher (1976): Back when recording a save was much more difficult algorithm to achieve, Brewer was the franchise leader with 126 when he retired, and he needed more than 800 innings and 300 games over a 12-year span to do that. He was also on the 1973 NL All-Star team at at a time when the Dodgers used to refer to the team’s bullpen as “The Brewery.” He’s still in the Top 5 of the franchise save leaders.

Mack Calvin, Los Angeles Lakers guard (1976-77): The Long Beach Poly prep star who went onto Long Beach City College and then showed enough at USC for two years to attract pro scouts was actually a draft pick by the hometown Lakers, albeit the 14th round in 1969. The ABA’s Los Angeles Stars looked more attractive to him, and that’s where he landed (wearing No. 20) with coach Bill Sharman. Calvin averaged 16.8 points per game to make the ABA All-Rookie Team, and the Stars went to the ABA Finals before losing to Indiana. He had a 44-point game during the division semifinals against Dallas and averaged 15.8 points and five assists a game in the six-game finals. The next five seasons with Florida, Carolina and Denver, Calvin was a five-time ABA All Star. The ’76-’77 season was split between Denver, San Antonio and finally the Lakers (for 12 games) before he was dropped from the roster and sat out a year. He came back for two more NBA seasons with Utah and Cleveland. As an assistant coach with the Los Angeles Clippers, Calvin took over as head coach for two games in 1992.

Have you heard this story

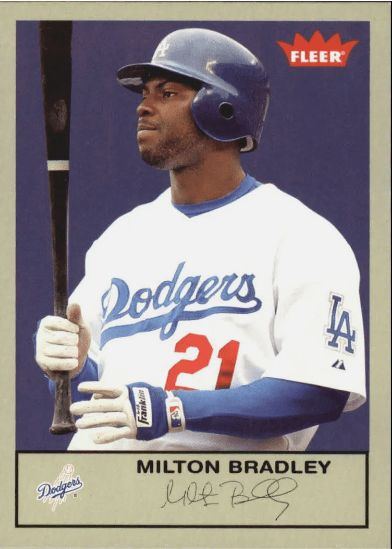

Milton Bradley, Los Angeles Dodgers outfielder (2004 to 2005):

“Trouble” or “Anger Management” were not products that the Milton Bradley board game company created, but they could summarize the season-and-a-half this former Long Beach Poly High standout spend with the Dodgers, one of eight teams he suited up for in 12 years. Bradley, whose birthday of April 15 was the same day all of MLB honors as Jackie Robinson Day, once said about how he had No. 21: “That’s the number they gave me in rookie ball, so I just kind of stuck with it. You know, you can’t wear 42 anymore, so I always said, 21 is half of 42; if I can be half of the player, half of the person, Jackie Robinson was, then I will have been a success. That’s my motto.”

His first major display of his volatile nature was being handed a four-game suspension by the league for throwing a bag of balls onto the field following his ejection from a game when he argued balls and strikes. He was suspended for the last week of the regular season on ’04 when he reacted to a fan who threw a bottle at him following an error by throwing it back at the fan and yelling at him, leading to another ejection. In October of ’04, during the NL playoffs, Bradley got into a clubhouse argument with the Los Angeles Times’ beat reporter. He returned in ’05 and hit.290 in 75 games before tearing knee ligaments. That offseason, the Dodgers swapped general managers, and Ned Colletti’s first deal was to swap out Bradley to Oakland for a prospect named Andre Ethier.

While Bradley was a Dodgers’ nominee for the Roberto Clemente Award for his work with the team’s non-profit foundation, he was accused of domestic abuse in 2005 (no charges filed), and more accusations after that, to the point where he was convicted of physically attacking his wife and was sentenced to 32 months in prison. In 2018, he remarried and was again charged with spousal battery, leading to probation and counseling. “When we traded for Milton, I think we knew everything that came along with it,” former Dodgers GM Paul DePodesta once told ESPN. “We knew the past, we don’t necessarily think that everything’s going to be completely different because he came to a different place. That’s fine. I would take nine Milton Bradleys if I could get them.” Or, maybe, one Either, who would play for the Dodgers all 12 of his MLB seasons with two All Star appearances, a Silver Slugger and Gold Glove.

Yu Darvish, Los Angeles Dodgers pitcher (2017):

The Japanese star import became available at the ’17 trade deadline as his Texas Rangers’s contract was coming up. The Dodgers rented him for three prospects. Darvish finished 4-3 with a 3.44 ERA in nine starts down the stretch, including an ERA of 0.47 ERA over 19 1/3 innings in his last three starts. In the NLDS and NLCS, he posted a win against Arizona and Chicago, allowing just two runs over 11 1/3 innings while striking out 14 and allowing one walk. But in Game 3 of the World Series at Houston, Darvish fell into the Twilight Zone — he lasted just one and two-third innings as the Astros posted four runs in the bottom of the second. It was the first time he failed to get a strikeout in an outing and he managed only one swinging strike in 49 pitches. Hear any trash cans banging? (Adding insult to it all, Houston’s Yuli Gurriel made a gesture in the dugout after hitting a home run, stretching the sides of his eyes and using the slur “chinito,” and received a five-game suspension by MLB Commissioner Rob Manfred — but still allowed to play in the World Series, so the punishment came to start the 2018 season). Darvish came back to start the decisive Game 7 at Dodger Stadium, quickly trailed 2-0, and a George Springer homer in the second inning meant Darvish again was gone after 1 2/3 innings. “If you ask me if I got hit in Game 7 because they stole signs, I don’t think so,” Darvish later said. Darvish’s Game 7 start was his last with the Dodgers. He signed a six-year, $126 million contract with the Cubs that offseason. Since reports of the Astros stealing signs emerged, Darvish said he has gotten apologies from Dodgers fans who blamed him for the losses. He responded: “I’m not looking for that. I don’t want them to change their minds.”

Dominique Wilkins, Los Angeles Clippers forward (1994): The eventual Basketball Hall of Famer who spent his first 12 seasons as The Human Highlight Film in Atlanta became the star attraction of another horror genre when Clippers GM Elgin Baylor decided to make a post ’94 NBA All Star Game trade for him. The Hawks gave up him and a 1994 first-round draft pick for All-Star Danny Manning, who was six years younger. Wilkins pulled on the No. 21 tank top and played out the final 25 games for the 27-55 Clippers, averaging 29.1 points a game, and left that summer to Boston. The Clippers used that pick from Atlanta (after taking Cal’s Lamond Murray at No. 7 overall) to select Louisville guard Greg Minor at No. 25, then traded him with Mark Jackson to Indiana for rookie Eric Piatkowski, Pooh Richardson and Malik Sealy.

Mark Pryor, USC baseball pitcher (2000 to 2001): After transferring from Vanderbilt, Prior led the Trojans to the College World Series in two straight years. As a junior, his 15-1 record and 1.69 ERA, plus 202 strikeouts in 138 innings with just 18 walks, won him the Golden Spikes Award. He struck out 10 or more hitters in a game 13 times, including a 13-strikeout effort against Georgia in the College World Series. His 202 strikeouts set a single-season record for the Trojans. He was the No. 2 overall pick by the Chicago Cubs in the 2001 MLB Draft, after Minnesota took home-town favorite Joe Mauer. Prior became the Dodgers bullpen coach in 2018 and took over as pitching coach in 2020 and had been wearing the No. 99 under his blue sweatshirt.

Liz Masakayan, UCLA women’s volleyball (1980 to 1984): She played Little League baseball in Santa Monica at age 10 — the first year girls were allowed to play because of Title IX. At Santa Monica High, she was on the first girls soccer team, ran track and also tried out for volleyball. At UCLA, she won the Broderick Award as the nation’s top volleyball player after the Bruins won the 1984 NCAA championship. Segueing into beach volleyball, Masakayan paired with Karolyn Kirby as one of the most dominant women’s teams, winning 29 tournaments. She and Elaine Youngs almost qualified for the 2000 Sydney Olympics. Masakayan ended up with 47 beach tournament wins and returned to coach at UCLA. She was inducted into the UCLA Athletic Hall of Fame in 1996.

We also have

Kobe Brown, Los Angeles Clippers forward (2023-24)

Ronny Turiaf, Los Angeles Lakers forward (2005-06 to 2007-08), Los Angeles Clippers forward (2012-13)

Kareem Rush, Los Angeles Lakers guard (2002-03 to 2004-05), Los Angeles Clippers guard (2009-10)

Eric Ball, UCLA football running back (1984 to 1988)

Shon Tarver, UCLA basketball forward (1990-91 to 1993-94)

Cedric Bozeman, UCLA basketball guard (2001-02 to 2005-06)

Anyone else worth nominating?

Great post! Thanks for sharing this.

LikeLike