This is the latest post for an ongoing media project — SoCal Sports History 101: The Prime Numbers from 00 to 99 that Uniformly, Uniquely and Unapologetically Reveal The Narrative of Our Region’s Athletic Heritage. Pick a number and highlight an athlete — person, place or thing — most obviously connected to it by fame and fortune, someone who isn’t so obvious, and then take a deeper dive into the most interesting story tied to it. It’s a combination of star power, achievement, longevity, notoriety, and, above all, what makes that athlete so Southern California. Quirkiness and notoriety factor in. And it should open itself to more discussion and debate — which is what sports is best at doing.

The most obvious choices for No. 71:

= Brad Budde: USC football

= Tony Boselli: USC football

= Kris Farris: UCLA football

= Joe Schibelli: Los Angeles Rams

The not-so-obvious choices for No. 71:

= John Ferraro: USC football

= Randy Meadows: Downey High football

The most interesting story for No. 71:

John Ferraro: USC football offensive lineman (1943-1944, 1946-1947)

Southern California map pinpoints:

Cudahy, L.A. Coliseum, Los Angeles City Hall

The cover of the 1946 Street & Smith’s Football Pictorial Yearbook asks readers to spend a quarter of a dollar for its preview the upcoming college football season. On this “national gridiron review,” John Ferraro offers a million-dollar glare.

The only hint on the cover that it’s him comes from a small caption off his right shoulder that reads “FERRARO U.S.C.” In the table of contents, his full name appears along with the photographer who took the special Kodachrome shot.

Ferraro had earned attention as a USC All-American tackle in ’43 and ’44. Now he was coming back to play after military duty during World War II in 1945. There were others to consider for the preview cover — Army’s Glenn Davis, “Mr. Outside” out of Bonita High in La Verne who had finished second in the Heisman Trophy in ’44 and ’45 would finally win it outright in ’46. Teammate Doc Blanchard, “Mr. Inside,” who won the Heisman award in ’45, and would finish fourth in ’46.

But the publishers picked Ferraro. Kodachome had that affect, apparently. And maybe the regional interest.

“If any tackle in this land of ours has ever played better ball, he must be Superman and Hercules rolled into one,” Braven Dyer bravely wrote for Los Angeles Times in 1944 after Ferraro pushed the Trojans to a 28-21 victory at the Coliseum over the San Diego Naval Training Station Bluejackets. “When Big John goes to work, he’s dynamite.”

That was part of the journalism superlative use in that time, and at the Times.

But the part that holds true today: If any Los Angeles civic leader is tenacious enough to accomplish something for the good of the town, he or she could be measured up to John Ferraro, a Rose Bowl legend and U.S. Navy vet rolled into one, and the one who started the heritage of USC standout linemen sporting the No. 71.

The story

In the cable-connected tapestry of Los Angeles, Cudahy often doesn’t make the cut when trying to recite all the important or influential cities. No matter how many dramatic drone shots are featured on the city’s official home page. In L.A. County, it remains the second-smallest city (next to Hawaiian Gardens) but it has one of the highest population densities of any incorporated city in the U.S., according to its department of information.

The city was in the news in 2020 when a Delta Air Lines flight from L.A. to Shanghai had to turn around and dump jet fuel before an emergency landing at LAX. The fuel landed on Cudahy, mostly on an elementary school, as the city was already reeling from having toxic sludge from a nearby battery plant contaminating its land.

Maybe think of it this way: If Beverly Hills is known as the 90210 zip code, Cudahy is dialed in at 90201. Population 22,294 amidst 1.23 square miles. More rodeo-minded than Rodeo Drive.

Cudahy wasn’t incorporated until 1960, yet biographies about John Ferraro say he was born there in 1924, in the “working class suburb” south of L.A. just west of where the 710 Freeway would be deemed to connect Long Beach to Alhambra, necessary for trucking deliveries and those looking for card casinos in nearby Bell Gardens and City of Commerce. Cudahy was named after a meat packing baron who bought the 2,700-some acres to sell off to farmers moving from the Midwest, bring their horses and chickens, and exist near the San Gabriel River.

Ferraro’s Italian immigrant parents ran a macaroni factory to help feed their family — John was the youngest of eight — but it went under during the Depression.

Ferraro went to nearby Bell High, Class of ’42, and found his calling on the football field as an All-City team selection. But the story goes that Ferrero’s entry point into a USC scholarship came because a) he was big and b) and a good friend of a player Trojans head coach Jeff Cravath really wanted. The friend (wish we knew who that was) didn’t pan out. But the 6-foot-4, 245 pound Ferraro did as the left tackle in his first season.

Note that in the bio for his induction into the College Football Hall of Fame in 1974 it starts this way:

“Destined to become Police Commissioner for the city of Los Angeles, California, ‘Big John’ Ferraro started working in the enforcement business as a two-time All-America tackle at the University of Southern California.”

That just scratches the surface.

It recounts how the 1943 team in Ferraro’s freshman year — a season where many teams in the country went dormant during World War II — finished its abbreviated Pacific Coast Conference season with a 29-0 win over Washington in the ’44 Rose Bowl before 68,000.

Add to that: It was the seventh shutout win the Trojans had that season. This was also the only time teams from the same conference would play in the Jan. 1 contest because of travel restrictions from the war effort. General Eisenhower, stationed in Western Europe, allowed U.S. troops who weren’t on the front lines to listen to the special radio broadcast of the game.

The bio goes on about how Ferraro became an All-American in ’44, as USC won another conference title capped off by a ’45 Rose Bowl win, this time 25-0 over Tennessee before 93,000.

Add to that: Ferraro blocked a Vols punt minutes into the game. Teammate Jim Callahan carried in 30 yards for a touchdown and a lead that wouldn’t be challenged.

In 1945 Ferraro was off as an ensign in the U.S. Navy. Add to that: He served on a tanker stationed in the Bay Area with Warren Christopher, who would become Secretary of State under President Bill Cliton. That friendship with Christopher would spark Ferraro’s future interest in politics.

But first, Ferraro returned to USC for his final two seasons. A back injury hampered his play in ’46, but he still was All-Coast team and second team All-America as the 6-4 Trojans finished the season with a 20-13 win at Tulane in late December.

Ferraro’s final year of ’47 resulted in another first-team All-America pick. USC went 6-0 in the PCC, shut out UCLA 6-0 before 102,000 in Nov. 22, and was ranked No. 3 when it lost the next week to No. 1 Notre Dame 38-7 in the season finale. The No. 8 Trojans still went back to the ’48 Rose Bowl, but was pinned down by a 49-0 loss to No. 2 Michigan (from the Big Nine Conference) before 93,000 in Ferraro’s final game.

Ferraro was picked No. 46 overall in the 1946 NFL draft by the Green Bay Packers but more than half the draftees didn’t sign. He took his degree in business administration to something that would be more productive. Starting in 1951, Ferraro was a successful insurance broker. It made him plenty wealthy. And able to scratch the political itch.

In ’53, mayor Norris Poulson appointed Ferraro as L.A.’s police commissioner, a 13-year run that culminated with his oversight of reaction to the Watts Riots of ’65.

When he appointed to the Los Angeles City Council by mayor Sam Yorty in 1966 from among 13 applicants to fill a vacancy of the position to represent the fourth district, Ferraro would stay in that chamber an unprecedented 35 years, re-elected nine times, right up until his death.

When he joined the City Council, carpenters had to remove the top drawer of his desk so he could fit his legs underneath.

Through that period, Ferraro was City Council president for 18 total years (1977 to 1981, and from 1987 to his death in 2001), and president pro-temp from ’75 to ’77. He was often the acting mayor with Tom Bradley was out of town. Ferraro’s committee appointments often set the direction of policy making.

The years in between were spent an unsuccessful run on the L.A. County Board of Supervisor as well as an 1985 campaign to be the mayor of Los Angeles, a spot kept for a fourth term by Bradley, himself quite the track and field athlete during his days at UCLA before becoming a police officer.

The sports-related connections that Ferraro became known for was helping bring the 1984 Summer Olympics to Los Angeles and provide a pathway for developers to make Staples Center happen in the South Park area of L.A. to help revitalize the area.

“John Ferraro is the unsung hero in this thing,” George Mihlsten, an attorney for Staples Center developers Ed Roski Jr. and Philip Anschutz, said as the completed center prepared for its opening. “He made the deal happen in L.A.”

Ferraro maintained he didn’t seek attention for his city representation. He just wanted to push the team forward. He wanted to be a behind-the-scenes deal maker. Fix pot holes. Keep the garbage trucks running. Whatever it took to help people.

A peacemaker who all the while knew how to navigate the hand-to-hand combat of local politics.

“I was a tackle,” he says, comparing his tenure on the council to his days on the playing field, to the Los Angeles Times in 1985. “Sure, we never got any glory, no headlines, and that has been my philosophy.”

In 1973, the College Football Foundation honored Ferraro with the NCAA Silver Anniversary Award, given to career achievement to student athletes on their 25th anniversary as college graduate.

The Councilman from Cudahy — with or without the Kodachrome mug shot — just did his job coolly and confidently. Or has his friend Warren Christopher said: “He possessed the two indispensable qualities for a public official: common sense and character.”

When Ferraro died at age 76, his Los Angeles Times obituary explained how Mayor Richard Riordan with there with family members.

“I know of no one who represents the heart and the soul of Los Angeles more than John Ferraro did. He was a big man, he was a strong man, but he was a loving man–a person who put Los Angeles first and his own agendas last.”

The news was announced in council chambers by President Pro Tem Ruth Galanter. Fighting tears, she told a reporter, “We are all sort of his children here. . . . It’s really hard to lose your dad.”

“In the wake of term limits, the council has not only lost its institutional memory, but it has also lost its single most important institution,” said county Supervisor Zev Yaroslavsky, who sat on the council 19 years with Ferraro.

The Council Chambers are named in his honor. There is the John Ferraro Building on Hope Street, formerly the Department of Water and Power. When they put him the Coliseum’s Court of Honor in 2000, Los Angeles Times columnist T.J. Simers wrote: “Make it a real Court of Honor for the living such as Peter Ueberroth, (John) Argue and Ferraro, who dedicated a portion of their lives to better L.A and what might go on in the Coliseum. And make it a memorial for the greats of the past who have contributed so much.”

He was part of the second class of the USC Athletic Hall of Fame induction in 1995, a year before he was included as a Rose Bowl Hall of Fame selection in 1996.

In 2014, it was announced that there would be a $10.5 million renovation of the John Ferraro Athletic Fields, the city’s largest soccer facility, a 26-acre site where more than 340,000 players each year compete. All in his Fourth District of Griffith Park.

It was somewhat interesting to see that on USC’s 2024 lacrosse roster, a junior attacker named Mia Ferraro from Philadelphia is on the squad wearing No. 9. The school says she is not related to John Ferraro. But maybe it’s just comforting to see a Ferraro name back on a USC jersey.

And, in the Los Angeles Coliseum’s Memorial Court of Honor:

Who else wore No. 71 in SoCal sports history?

Make a case for:

Brad Budde, USC football offensive lineman (1976 to 1979):

The first true freshman to start for the Trojans in the post-WWII era, Budde’s 6-foot-4 and 282-pound frame formed a wall on the USC offensive line for the likes of Charles White and Marcus Allen. As a senior, along with being a unanimous All-American, USC Offensive Player of the Year, USC Most Inspirational Player and Academic All-American, Budde was selected as the first and only Lombardi Award winner in USC’s history. He became a College Football Hall of Fame inductee in 1990, later honored by the USC Athletic Hall of Fame in 1999 and the Rose Bowl Hall of Fame 2010. When he was the 11th overall pick in the NFL draft by Kansas City, he joined his father, Ed Budde, as the first father/son combo drafted in the first round by the same team and play the same position. In 2025, the Associated Press named its all-time All-American college football team to mark the 100th anniversary of the award that began in 1925. Budde was second-team offensive guard. After seven years in the NFL with Kansas City, Budde earned a Masters in physical therapy from Loma Linda University, Budde has served as president of Budde Physical Therapy Inc. rehabilitating senior citizens in Orange County. He was also an offensive line coach at San Clemente High and Orange Coast College.

Tony Boselli, USC football offensive lineman (1991 to 1994):

While Trojan standouts such as Morton Kaer, Harry Smith and Ralph Heywood wore No. 71 before “Big John” Ferrero, there wasn’t anyone quite as big in statue as the 6-foot-8, 335-pounder to wear it after him like Boselli. He was inducted into College Football Hall of Fame in 2014, a reflection of his three-time All-American status. His USC Athletic Hall of Fame induction in 2012 reflects his status as the ’94 team captain and MVP. “I’ve coached three Hall of Fame linemen — Anthony Munoz, Jackie Slater and Tony Boselli,” former USC head coach John Robinson once said. “They were all kind of equal in terms of the potential they had. Tony had marvelous size, speed, balance and he was a mean SOB.” Boselli became the first player picked by two NFL expansion teams — by Jacksonville in 1995 (second overall in the draft) and by Houston in 2002 (in the expansion draft, injured the entire season) and was inducted into the Pro Football Hall of Fame in 2022 for his five Pro Bowls in seven seasons. He is also in the Cotton Bowl Hall of Fame to capture his game MVP performance in USC’s 55-14 win over Texas Tech in 1995 — USC’s offensive had 578 yards. In ESPN’s 2020 list of the 150 greatest college football players in the game’s first 150 years, Boselli ranked No. 144 with this tribute: “The rebuilding of USC football in the early 1990s just might have begun with the signing of Boselli, who didn’t sign with his home-state, national-champion Colorado Buffaloes in order to go to USC. Boselli rapidly remade the prototype of the ideal offensive tackle … made All-Pac-10 as a freshman, when the Trojans went 3-8. By his junior year, USC won a share of the conference championship.”

Deuce Lutui, USC football offensive guard (2004 to 2005):

The consensus All-American from Tonga weighed in at 370 pounds, the heaviest Trojans player of all-time. He survived an auto accident at age 6 that killed his sister and disabled his father. “It was a trauma for all of us,” said Lutui, who spent seven years in the NFL. “I was determined after that to make something of my life. My parents were hurt, but I felt they had brought us to this country for a purpose…As a teenager, I had to take care of the family. I was the one paying the bills. My parents, coming from the Tongan Islands, weren’t too familiar with the American system.”

Charles Brown, USC football left tackle (2006 to 2009):

A consensus All-American from Diamond Ranch High in Pomona came to USC as a tight-end recruit before he was moved on the offensive line. He finished All-Pac-10 and won the Morris Trophy as the conference’s top offensive and defensive lineman. He finished his college career after appearing in 48 games with 27 starts and then played six years in the NFL.

Kris Farris, UCLA football offensive tackle (1995 to 1999):

The 6-foot-8 standout from Rancho Margarita Catholic High School was recognized as the Outland Trophy winner and a consensus first-team All-American as a senior. “I did go to UCLA to study film,” he said, “but I realized my first love was football. I never circled back on that career after football – I put all of my energy and focus into football and never prepared myself for that kind of work in film. I didn’t get my major in film – had no contacts in the business. At 26 it just wasn’t my goal anymore. I still do love film though.”

Joe Schibelli, Los Angeles Rams right guard (1961 to 1975):

The Notre Dame standout played 202 games for the Rams, starting 193. He was part of a veteran offensive line that included tackle Charlie Cowan, who played with Scibelli for 15 years, and guard Tom Mack, who was with the Rams from 1966 through 1974. Scibelli played in the Pro Bowl in 1968, and he was a team co-captain during his last 10 years with the Rams. He was named the Rams’ most valuable offensive lineman five times, and five of the Ram teams on which he played won their division. He was an All-Pro selection in 1973.

Have you heard this story:

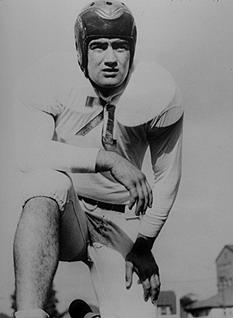

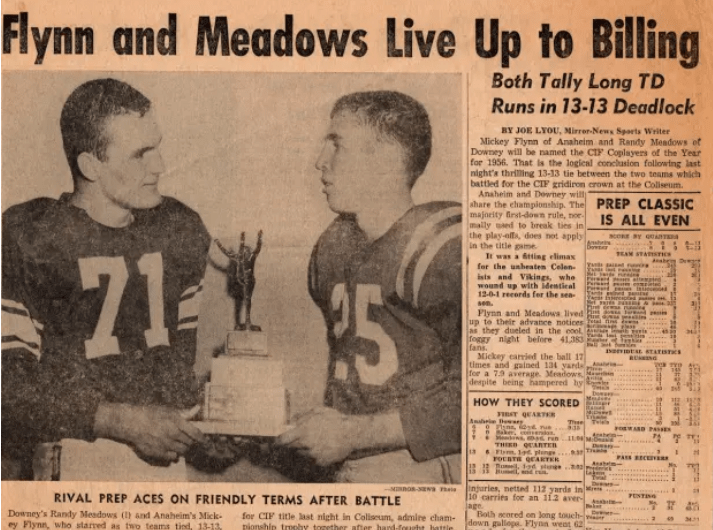

Randy Meadows, Downey High football running back (1954 to 1956):

In a senior season where he the led the CIF in scoring with 196 points in 13 games, Meadows’ greater moment of fame in Southern California came when his 12-0 Downey team faced 12-0 Anaheim and Mickey Flynn for the the CIF championship on Dec. 14, 1956 at the Coliseum. In dense fog, before an estimated 50,000 fans, Meadows injured his shoulder tackling Flynn in the first quarter. But he came back and had 112 yards rushing on 10 carries and scored on a 69-yard TD run. The game ended in a 13-13 tie, co-champs were declared, and it has been documented in the film “A Last Hurrah.” Meadows, who shared the 1956 CIF Player of the Year award with Flynn, became his teammate at the following Shrine East-West All Star game, which drew another 85,000 fans at the Coliseum. Meadows, who went to USC briefly, never appeared in a varsity game and suffered a career-ending injury while playing for a service team in the Army. He died in 2000 at 62 after a long battle with cancer.

We also have:

Craig Novitsky, UCLA football offensive guard (1990 to 1993)

Bruce Davis, UCLA football defensive tackle (1975 to 1978)

Reggie Doss, Los Angeles Rams defensive end (1978 to 1987)

Anyone else worth nominating?

Wow! I didn’t think anyone remembered that Anaheim vs. Downey game back in ’57.

LikeLiked by 1 person