This is the latest post for an ongoing media project — SoCal Sports History 101: The Prime Numbers from 00 to 99 that Uniformly, Uniquely and Unapologetically Reveal The Narrative of Our Region’s Athletic Heritage. Pick a number and highlight an athlete — person, place or thing — most obviously connected to it by fame and fortune, someone who isn’t so obvious, and then take a deeper dive into the most interesting story tied to it. It’s a combination of star power, achievement, longevity, notoriety, and, above all, what makes that athlete so Southern California. Quirkiness and notoriety factor in. And it should open itself to more discussion and debate — which is what sports is best at doing.

The most obvious choices for No. 41:

= Jerry Reuss, Los Angeles Dodgers

= John Lackey, Anaheim Angels

= Elden Campbell, Los Angeles Lakers

= Glen Rice, Los Angeles Lakers and Clippers

The not-so-obvious choices for No. 41:

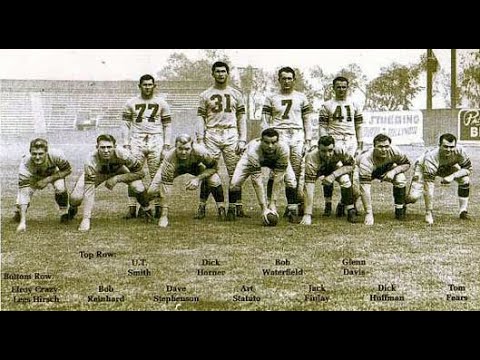

= Glenn Davis, Los Angeles Rams

= Ken Norton Jr., UCLA football

= Jeff Shaw, Los Angeles Dodgers

The most interesting story for No. 41:

Glenn Davis, Los Angeles Rams running back (1950 to 1951)

via Bonita High

Southern California map pinpoints:

Claremont, La Verne, Pomona, Los Angeles Coliseum, La Quinta

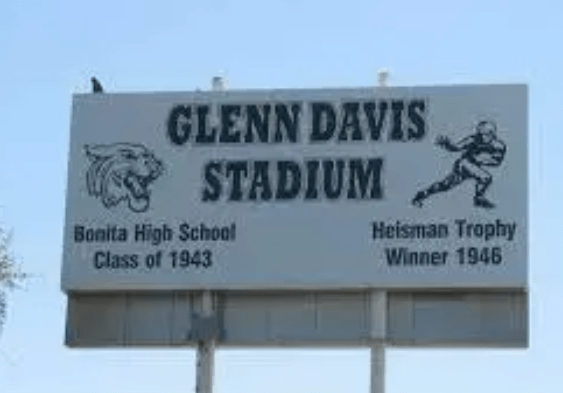

Next to Smudgepot Game Trophy — which, to some, carries more importance as far as bragging rights — Glenn Davis’ 1946 Heisman Trophy sits in the main office at Bonita High School in La Verne. It’s rather unassuming in a glass case, with all sorts of newspaper clippings behind it.

The Army tailback known as “Mr. Outside,” who had been on the outside looking in as he was the Heisman runner up as both a sophomore and a junior, became just the 12th recipient in the award’s history, having claim to the most “outstanding college football player in the United States” as deemed by the Downtown Athletic Club of New York City.

On Davis’ Heisman, there’s a small, noteworthy addition made to the original plaque in the bottom left corner. “Bonita High School 1940-1943.”

To the kid known as the “Claremont Comet,” that’s what most mattered. To the school, it was an honor to go with its pride.

“I don’t think there’s too many high schools in the country with a Heisman Trophy in their possession,” said then-Principal Bob Ketterling, who arrived a couple of years after the handoff. “People walk by and do a double-take.”

Davis was the first Heisman Trophy winner with roots in the California Interscholastic Federation’s Southern Section. It would be years later when, as a member of the Los Angeles Rams, the home-grown star was back in a spotlight, playing in two NFL championship games during his only two seasons.

The background

Born in Claremont on Christmas Eve 1924 — that’s what his headstone at West Point states, and it is what we will go with even though some sources say he was born on the actual Christmas day or the day after Christmas — Glenn Davis was nicknamed “Junior” as a family joke. He arrived 90 minutes after his twin brother, Ralph, who was given their father’s name.

Ralph and Irma Davis owned grove of lemon and orange trees in La Verne, and the boys worked summer as fruit pickers. They also were defense workers at a plant on Olympic Blvd., in L.A., when they were older.

At Bonita High, Glenn Davis was a four-star athlete, earning 13 varsity letters in football, basketball, baseball and track. Wearing No. 22, his claim to fame was scoring 236 points in his senior year. He scored five touchdowns to lead the Bearcats to a 39-6 win over Newport Harbor in the CIF-SS Class A title game.

Fame also came in a 41-12 win over South Pasadena during the playoff run to the title. Davis became the subject of a Ripley’s “Believe It Or Not” item. Running the Bonita Single Wing offense, Glenn threw a touchdown pass to Ralph during that game. But it was called back. His team was offside. So they did the same play — another TD pass from Glenn to Ralph, again, canceled by an offside call. On the third try, Glenn threw another TD pass — Bonita was called for holding, thus it was also nullified.

On the fourth try, Glenn faked a pass, tucked the ball in, and ran for a 55-yard touchdown. At that moment, he became known as the “Claremont Comet.”

The 1942 CIF-SS Player of the Year (and first-team All CIF with his brother Ralph on the second team), Glenn led his team to an 11-0 mark. He was also All-CIF in baseball and he received the 1943 Knute Rockne Trophy as the best track star in Southern California, running the 100 yards in 9.7 seconds and the 220 in 20.9.

Glenn’s plan was to move onto USC for football, but he was offered a Congressional appointment to the Army Academy by Congressman Jerry Voohis. Glenn agreed to go only if his brother Ralph could join him. They enlisted.

West Point may not have known what it was getting until Glenn’s plebe year when he took the “Master of the Sword” physical fitness test. A combination of the 300-yard run, a “dodge” run, a vertical jump, parallel bar dips, softball throw, situps and chins and standing broad jump would earn an average score of 540 for the participants. Davis scored a 926.4 out of 1,000 — an all-time high — and later increased it to 962.5.

In 1943, Davis enrolled but he was not the scholar student. He was asked to leave at the end of the season. He came back to Webb Prep School in Claremont to finish a four-month math course that allowed him to re-admit at West Point in 1944-45 back as a plebe.

At 5-foot-9 and 170 pounds, Davis had to rely on his leg strength, change of speed and a strong stiff arm on a defender — not unlike the pose presented on the Heisman Trophy.

Lettering in football, track and as a center fielder in baseball, Davis attracted the attention of Brooklyn Dodgers president Branch Rickey, who said he could earn $75,000 if he was willing to come to spring training with the team.

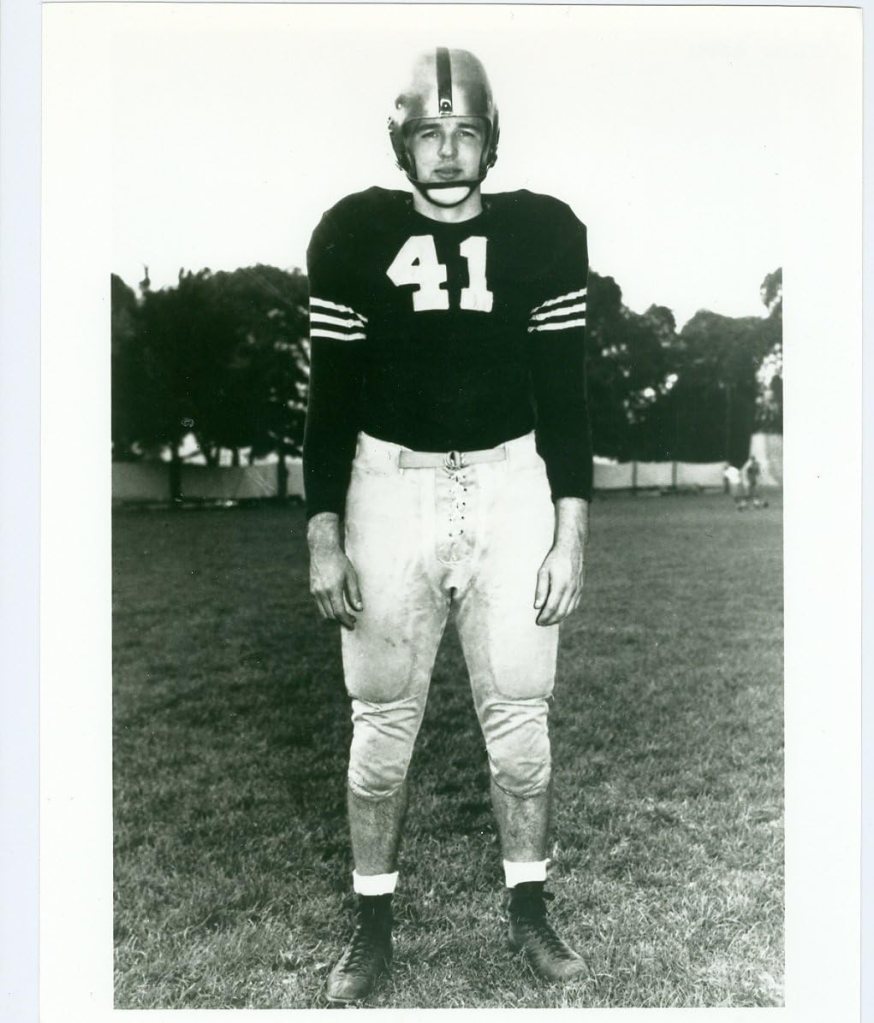

In 1944, the sophomore Davis finally sporting No. 41 led Army to a 9-0 record and No. 1 ranking as he accounted for 19 touchdowns. He led the nation with an average of 11.7 yards per carry. He scored 14 touchdowns rushing (667 yards on 58 carries), four TDs receiving (221 yards on 13 catches) and one passing (in six attempts, for 197 yards) to win the Maxwell Trophy, the Walter Camp Trophy and the Helms Foundation Trophy. Army finished undefeated for the first time in nearly 30 years. The prize win was 59-0 over Notre Dame.

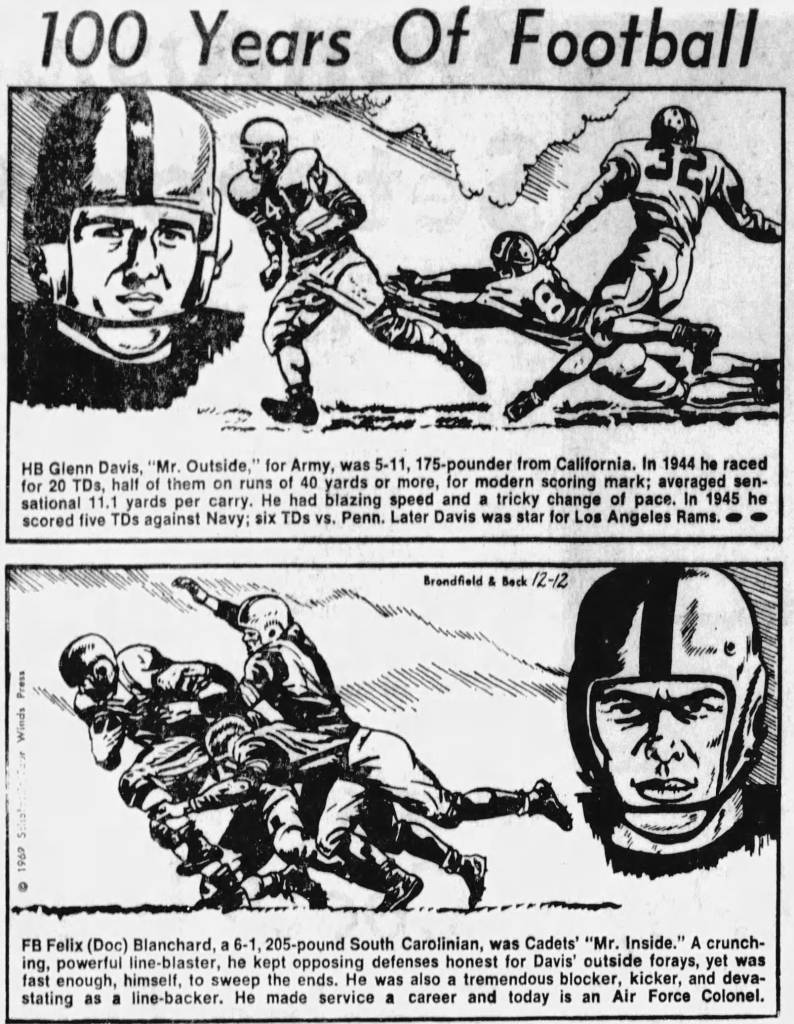

That year, he gained the nickname “Mr. Outside” for his skills to turn the corner of the line, while teammate Doc Blanchard was “Mr. Inside” for his ability to put his 235-pound body through the line. They became the “Touchdown Twins” and combined for 156 points together in ’44.

In the first of three All-American selection seasons, Davis finished second and Blanchard was third in the Heisman voting, behind winner Les Horvath, the senior halfback/quarterback from national champion Ohio State. Horvath would precede Davis in playing two seasons for the Los Angeles Rams (1947 and ’48), wearing No. 12.

By 1945, as Army again was 9-0 and ranked No. 1 all season long, Davis was second again in the Heisman, this time to teammate Blanchard. Both scored 17 touchdowns each for 204 points. Davis averaged an NCAA record 11.5 yards per carry and 103.3 yards a game (930 yards, 15 TDs) on the ground and 42.6 yards a game receiving (213 yards, two TDs).

The 1946 season saw Davis lead Army to another undefeated season, despite a tie against Notre Dame (which ended as the No. 1 ranked squad). Davis ran that season for 712 yards and seven touchdowns, had 356 yards receiving with six touchdowns, passed for 396 yards and four touchdowns, and played safety. Davis’ Heisman win (792 votes, over Georgia’s Charley Trippi and Notre Dame’s Johnny Lujack) came with teammate Blanchard finishing fourth (and Army quarterback Arnie Tucker fifth).

In his three years at Army, where the team was 27-0-1 and almost always ranked No. 1 in the nation, Davis piled up 2,957 yards rushing on 8.3 yards per carry — a long-time standing record. It resulted in 59 touchdowns. He also had 850 yards receiving as 12 TD catches. He passed for 1,172 yards.

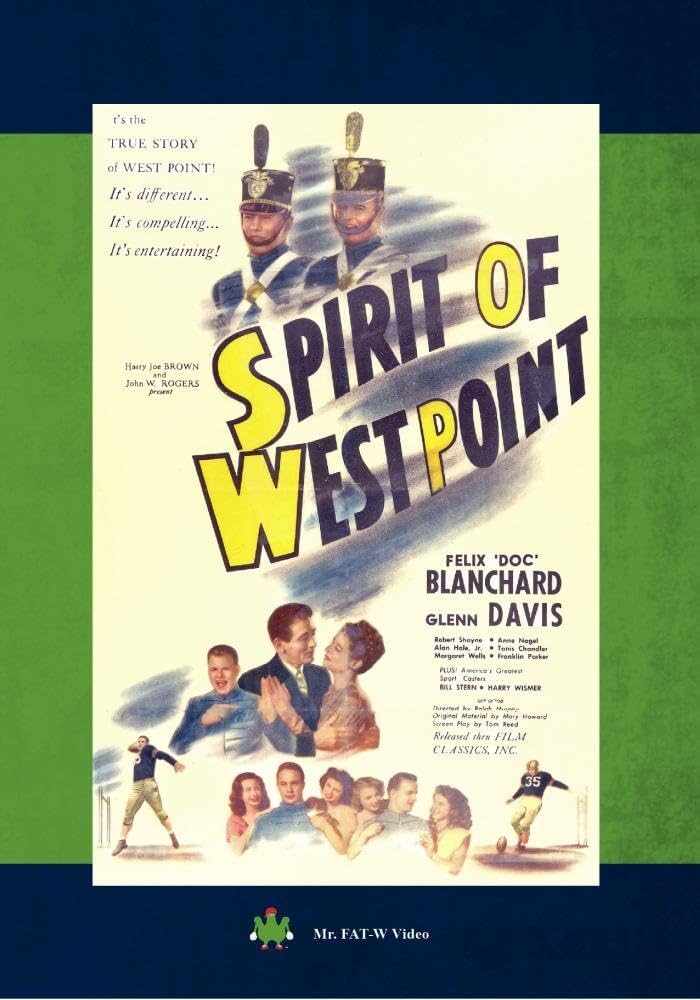

Hollywood got a hold of the Davis-Blanchard story and recruited both to star in “The Spirit of West Point,” where another former Heisman winner, Tom Harmon, played the role of a radio sportscaster.

Filmed at the UCLA practice field, Davis actually tore cartilage and ligaments in his right knee during the shoot. For what it’s worth, the film didn’t do all that well in reviews. The featured review on the IMdB.com called it “The Plan 9 of sports movies.”

Davis also had to fulfill his military obligation, serving in Korea, which means that while he was drafted by the NFL’s Detroit Lions, second overall in the ’47 event, he had to put that off.

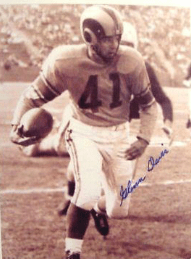

He would join the star-studded Los Angeles Rams for the 1950 season and kept wearing No. 41 once his obligation ended. Now listed at 5-foot-11 and 171 pounds at age 25, and despite the residuals of that knee injury, Davis was named to the Pro Bowl after a season where he ran for 416 yards on 88 carries and caught 42 passes for 592 yards, combining for seven touchdown.

In the 1950 NFL Championship Game on Christmas Eve, Davis scored on an 82-yard pass from Bob Waterfield for the first play after the opening kickoff in an eventual 30-28 loss to the Cleveland Browns in Cleveland, secured by Lou Groza’s 16-yard field goal with 28 seconds left. Davis had six yards rushing on six carries and one punt return for 14 yards.

In 1951, Davis re-injured his knee and was able to pile up just 290 yards rushing for the season. In the 1951 NFL Championship Game, during the Rams’ 24-17 loss at the Coliseum, Davis caught three passes for 10 yards, but also lost six yards on six carries. Sitting out the 1952 season, the Rams released him in September of ’53, ending his football playing days. It was time to move onto other things.

The legacy

In 2020, ESPN drew up a list of the Top 150 players in college football’s first 150 year history, and Davis was No. 18 with this writeup: Those who saw him play make Mr. Outside’s long list of records read like the dry text that it is. Two quotes from the book “The Heisman: Sixty Years of Tradition and Excellence” explain Davis’ greatness. First, Steve Owen, the coach of the New York Giants in the 1940s, declared Davis “better than Red Grange. He’s faster and he cuts better.” Additionally, Army teammate Bill Yeoman, the Hall of Fame coach of the Houston Cougars, said late in his life that Davis “is still the most phenomenal athlete I ever saw.” At 5-9, 170, Davis might have been too slight for today’s game. That’s assuming anyone ever laid a pad on him.

Legendary Army coach Earl “Red” Blaik was also known to say about Davis: He was “the best player I have seen, anywhere, anytime.” Blaik also called Davis’ shy demeanor as someone who was “bashful as a girl on her first date, even through he was an All American.”

Bonita High named its football field after Glenn Davis in 1987 — but it was not the stadium where he played. The Bonita High in Davis’ day was at the current site of Damien High, and the current Bonita campus wasn’t built until years after he graduated.

Inducted into the College Football Hall of Fame in 1961, Davis also found fame dating actresses Ann Blyth and Elizabeth Taylor and was briefly married to actress Terry Moore. Davis and wife Ellen Harriet Lancaster Slack were married for 43 years until her death. Davis and Slack had one son — named Ralph. In 1966, Davis married Yvonne Amenche, the widow of 1943 Heisman winner Alan Ameche.

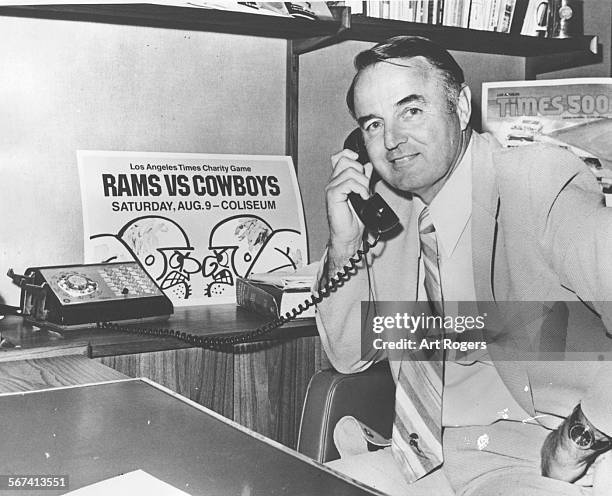

The Glenn Davis Award was created by the Los Angeles Times to honor the winner of its high school football player of the year. Davis worked at the Times as its special events director for fund raising, lasting 35 years before retiring to La Quinta.

As for the story of how Bonita High received Davis’ Heisman: A year before he died at age 80 in 2005 — soon to be buried at West Point near his coach, Earl Blaik — Davis said he just called the school one day and asked if anyone was there that day.

“I’m going to bring something over,” he told them.

Davis asked there be no publicity around the presentation. He left the Heisman off at the principal’s desk.

As he was leaving, Davis saw a trophy case with a small, non-descript award called the “Downtown Business Community” trophy that the school used to give to its top athletes.

Davis asked if he could take that one home instead, so he could remember his days at Bonita High.

“Nobody knew that he was going to give the Heisman to the school, and Glenn specifically asked for no cameras or no media coverage,” said Eric Podley, former head football coach at Bonita High School.

“I just happened to be walking outside the day he brought it. I saw a little old man and a little old woman walking along. I thought they were lost,” said Dan Harden, former Bonita athletic director. “Then I saw it. He was walking with his wife and just carrying it along, under his arm.”

As Davis told L.A. Times columnist Bill Plaschke in 2004 about the handoff: “It’s just a trophy. It’s not a life.”

Who else wore No. 41 in SoCal sports history? Make a case for:

John Lackey, Anaheim/Los Angeles Angels of Anaheim pitcher (2002 to 2009):

Best known: The Angels’ second-round 1999 draft pick from Abilene, Tex., made his major-league debut in June of 2002 at age 23, finishing up 9-4 with a 3.66 ERA in 18 starts. But there was far more to come. Lackey made five appearances in the 2002 playoffs, topped off as becoming the second rookie ever to start a World Series Game 7. He got the win in the Angels’ title clincher by allowing one earned run on four hits in five innings, leaving with a 4-1 lead. That was the first of three World Series championships he won in his career, capturing another with Boston and the Chicago Cubs. With the Angels for eight of his 15 MLB seasons, Lackey was 102-71, winning 19 games and a league-best ERA of 3.01 during his AL All Star season of 2007, third in Cy Young voting.

Not well remembered: Lackey is the pitcher featured in a Derek Jeter Gatorade commercial (above), as actor Harvey Keitel was egging on the Yankees’ great to steal second base on “that Schemedrick.”

Jerry Reuss, Los Angeles Dodgers pitcher (1979 to 1987):

Best remembered: As a member of the NL All Star team in 1980, Reuss made a mound appearance at Dodger Stadium in the top of the sixth inning, striking out three and earning the victory as his team took a 3-2 lead in the bottom of the sixth. That season, Reuss was second in the NL Cy Young voting, winning 18 games and throwing a no-hitter in San Francisco that could have been perfect if not for a Dodgers’ first-inning error. Reuss’ nine years with the Dodgers were the longest of any of the eight teams he played for in his 22 MLB seasons — including one with the Angels in 1987 wearing No. 44. As a Dodger he went 86-69 with a 3.11 ERA in 201 starts that included 44 complete games, 16 shutouts and even eight saves. He also won Game 5 of the World Series against the New York Yankees (after losing Game 1).

Not well remembered: Reuss was scheduled to be the Dodgers’ 1981 Opening Day starter at Dodger Stadium. But the day before, he suffered a calf injury shagging fly balls in the outfielder and couldn’t make it. Burt Hooten was also ailing. Manager Tommy Lasorda asked 20-year-old Fernando Valenzula to make the appearance. The rest was pretty historic. Thanks, Reuss.

Lou Johnson, Los Angeles Dodgers outfielder (1965 to 1967)

Best remembered: “Sweet Lou” hadn’t played in a big-league game for two seasons before the Dodgers acquired him from Detroit before the ’64 campaign, and then the 31-year-old was called up to replace an injured Tommy Davis in 1965. As the Dodgers’ regular left fielder, Johnson hit .260 with 58 RBIs. Johnson’s two homers in the 1965 World Series included what turned out to be the game winner in Game 7 at Minnesota. Johnson moved to right field in ’66 and played 152 games with 17 homers and 73 RBIs, hitting .272 leading to another World Series appearance. After his career ended following recovering from a broken leg, he joined the Dodgers community relations department.

Not well remembered: On Sept. 9, 1965, the night Sandy Koufax threw his 1-0 perfect game in an hour and 43 minutes against the Chicago Cubs (and won his 22nd game), Johnson, hitting cleanup, got the game’s only hit and scored the game’s only run. Johnson walked to lead off the fifth inning, got to second on a sacrifice bunt by Ron Fairly (Cubs’ starter Bob Henley dropped the ball as he fielded it and may have gone to second but then had to throw to first), stole third and scored on a throwing error by Cubs’ catcher Chris Krug, a former Riverside Poly High standout (who also struck out to start the famous ninth inning). In the bottom of the seventh, Johnson broke up Henley’s no-hit bid with a flare over first base and just bounced fair and kicked foul, chased down by Cubs first baseman Ernie Banks. Johnson ended up with a double — and turned out to be the only player to reach base for either team.

Jeff Shaw, Los Angeles Dodgers pitcher (1998 to 2001):

Best known: Shaw posted 25 saves and a 2.55 ERA during the second half of the 1998 season after a trade with Cincinnati, convincing the Dodger to make him one the highest-paid closers in MLB by signing him to a three-year, $15 million contract at season’s end — or risk having him use a player option to leave as a free agent (which then-manager Tommy Lasorda wasn’t aware of when he made the trade). Shaw was the franchise leader in saves with 129 until Eric Gagne passed him in 2004.

Not well remembered: Shaw became the first player in baseball history to participate in an All Star game wearing a uniform for a club he had yet to play in a regular-season. On the Saturday before the 1998 All Star Game in Denver, GM Lasorda gave up promising Dodgers rookies Paul Konerko and Dennys Reyes to the Reds in exchange for Shaw, already named to the NL roster for what he did so far that season with Cincinnati (23 saves in 39 games with a 1.18 ERA, with an NL-best 42 saves in ’97). During the AL’s 13-8 win, Shaw pitched the eighth inning, giving up a run on three hits. In 2001, Shaw’s final MLB season, he made one last NL All Star team for the Dodgers at age 34. He faced two batters in the eighth inning, giving up a hit.

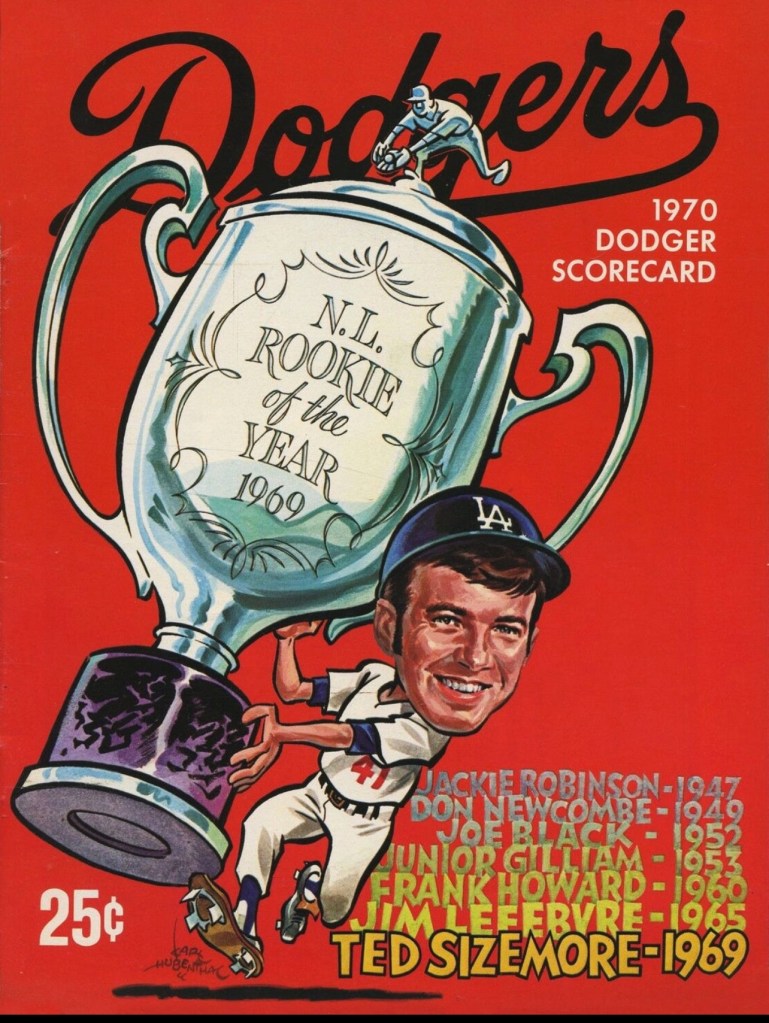

Ted Sizemore, Los Angeles Dodgers second baseman (1969 to ’70)

Best known: He started the ’69 season as the Opening Day shortstop, but was moved to second base within a few weeks when the Dodgers brought back Maury Wills. Posting a .359 batting average by the end of April, Sizemore ended up with 160 hits in 159 games and a .271 average to win the NL Rookie of the Year Award voting. He hit .306 his next year in 96 games, but the Dodgers, who originally drafted him as a catcher, decided to package him in a deal with St. Louis to get Dick Allen in 1970.

Not well remembered: The Dodgers made a deal with St. Louis in 1976 to get Sizemore back, dealing away Willie Crawford. The rumor was that Dodgers were about to deal shortstop Bill Russell to the Cardinals for Reggie Smith, but that never happened. After one season back in L.A. (as he wore No. 5), Sizemore was dealt to Philadelphia.

Ken Norton Jr., UCLA football linebacker (1984 to 1987):

Best known: The son of the heavyweight boxer by the same name, Norton came by way of Westchester High and made his way into the UCLA Athletic Hall of Fame in 1998 by leading the Bruins in tackles during his junior and senior seasons.In a career where was part of four winning bowl teams, and a finalist for the Butkus Award, the Bruins’ defensive MVP piled up 339 tackles at UCLA and was a second-round pick of the Dallas Cowboys.

Not well remembered: Norton returned in 2022 to be the Bruins’ linebacker coach after he spent six seasons coaching defense at USC (2004 to ’09).

Spencer Havner, UCLA football linebacker (2002 to 2005):

Best known: The four-year starter was a semifinalist for the Bednarik Award (nation’s top defender), the Lombardi Award (nation’s top lineman) and the Butkus Award (nation’s top linebacker) when he was also named UCLA’s Most Valuable Player in 2005. He led the Bruins with 99 tackles, 15 for a loss and three interceptions.

Not well remembered: In three NFL seasons, the 6-foot-3, 250-pounder was turned into a tight end with Green Bay in 2009 and caught 10 passes for 112 yards and four touchdowns that season from Aaron Rodgers.

Elden Campbell, Los Angeles Lakers center (1990-91 to 1998-99):

Best known: The 6-foot-11, 215-pounder from Morningside High of Inglewood who took off to Clemson University and came back to So Ca as the Lakers’ first-round (27th overall) draft pick in 1990 — and ended up scoring more points that decade (6,408) than any other Laker. He also ranks third in franchise history in blocks. The 1990s decade started with a Lakers roster that included the end of Showtime stars Magic Johnson, James Worthy and Byron Scott, and it ended with the arrival of Kobe Bryant and Shaquille O’Neal. As a starter from ‘93 to ‘97, Campbell averaged 13.4 points and 7.1 rebounds.

Not well remembered: During the 1998-99 season, Lakers GM Jerry West traded Campbell traded to Charlotte along with Eddie Jones for three-time All-Star small forward Glen Rice, who took the No. 41 that Campbell vacated. Campbell died at age 57 in 2025, the same year Morningside High closed.

Glen Rice, Los Angeles Lakers forward (1998-99 to 1999-2000), Los Angeles Clippers forward (2003-04):

Best known: Throughout a 15-year NBA career that started in Miami and went through Charlotte with three All-Star appearances, Rice established himself as a 3-point specialist that the Lakers felt they needed by trading for him midway through the ’98-’99 season. Rice averaged 17.9 points a game in 27 games to end that season (and averaged 18 points a game in the playoffs). For the ’99-’00 season, he averaged 15.9 points a game starting all 80 regular season games, then averaged 11 points a game in the Lakers’ six-game NBA Finals win over Indiana in 2000.

Not well remembered: Rice’s final NBA season with the Clippers were 18 games off the bench shooting 22-of-76 from the field (29 percent) and 5-of-28 from 3-point range (18 percent).

Have you heard this story:

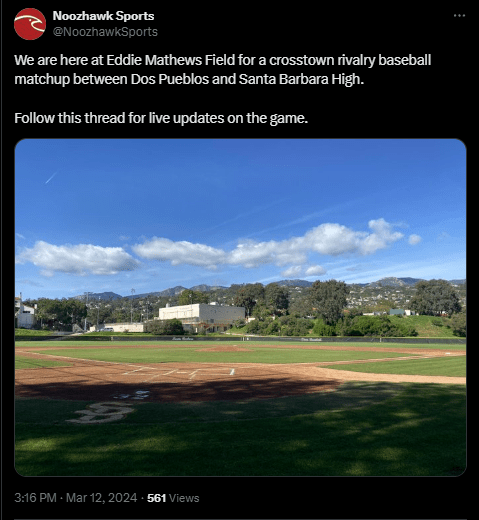

Eddie Matthews, Santa Barbara High baseball (1945 to 1949):

The Santa Barbara High baseball field sports his name because that’s where he drew attention prior to a Hall of Fame career with the Boston, Milwaukee and Atlanta Braves. The legend of Matthews on that field included those who claim to have seen him hit home runs over fences, buildings and swimming pools.

“I was a linebacker and fullback in football,” he once told the L.A. Times. “We played St. Anthony of L.A. in the football championship game at the Coliseum, but we lost because they had more first downs. Then we played in the baseball championship game at the old ballpark (Lane Field) in San Diego. I hit a home run, but we lost that one, too.”

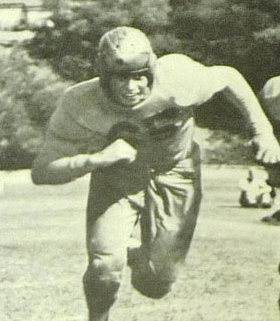

The “Santa Barbara Bomber” signed with the Braves at age 17 on the night of his high school graduation in 1949 and he was in team’s regular third baseman by age 20. The Braves retired his No. 41. What number did he wear playing baseball at Santa Barbara High? We aren’t sure. A 1948 yearbook shot shows him as a junior playing third base. But there is this photo of No. 65 playing football.

Matthews was a player, coach and manager with the franchise, including the team skipper on the night in 1974 when former teammate Hank Aaron hit his record-breaking 715th home run against the Dodgers. And a photo of him adorns the initial cover of Sports Illustrated in August of 1954.

Pasadena native and longtime Atlanta Braves slugger Darrell Evans was one of many who attended Mathews’ 2001 funeral in Santa Barbara Cemetery. Evans wore Matthews’ No. 41 while playing in Atlanta. “I think I still have some of the bruises from balls he hit at my chest,” said Evans, who played under Mathews. “He took the fear out of playing baseball. He taught me how to be a leader. He wanted me to be a leader. He is gone, but he is certainly going to live on with everybody here.”

Ron Shelton, a minor-league baseball player who would go on to be a Hollywood writer, producer and director, idolized Mathews growing up in Santa Barbara and wrote at the time of Mathews’ death: “If you lived in Santa Barbara — or Milwaukee, because the Braves moved there from Boston — you knew early on that two young hitting stars were about to become the most potent 1-2 home-run combination in baseball history. Two kids, really, Henry Aaron and Eddie Mathews. With one ‘t’, Mathews — that was a big thing for us kids. Spell his name right. He’s our guy. … I won the batting title at Santa Barbara High and was awarded the Eddie Mathews Bat, which was the school’s trophy for best batting average. Of all the trophies, plaques and honors I’ve received, this is the only one I can actually locate. It’s the only trophy you can carry out to the backyard and take a few cuts with.”

Quincy Olivari, Los Angeles Lakers forward (2024-25):

A headline on a Los Angeles Times story in mid-October of 2024 read: “Who is No. 41? The winning way Quincy Olivari introduced himself to Lakers nation.” When the Lakers had their annual media day in El Segundo prior to training camp for the 2024-25 season, Oliveri, an undrafted training-camp signee on a non-guaranteed contract deal became somewhat famous on the Internet one day for arranging to have his photo taken with LeBron James in the background of a TV interview being done with James’ son, Bronny. Oliveri then put in 11 points, with five rebounds and two assists during a 10-minute window in an exhibition game win in Milwaukee. “Yeeeeaaaahhhhh Q!!,” James posted on Instagram afterward. “They know who 41 is now.” Olivari was eventually signed to a two-way contract and went to the Lakers’ South Bay G-League team, using the mantra “Who is #41?” as his motivation. In the ’24-’25 season, Olivari played 10 minutes over two games, making one three-pointer.

We also have:

Clem Labine, Los Angeles Dodgers pitcher (1958 to 1960) Also wore No. 41 from 1950 to ’57 with Brooklyn

Mitch Kupchak, Los Angeles Lakers forward (1981-82) Also wore No. 25 from 1983-84 to 1985-86

Swen Nater, Los Angeles Lakers center (1983-84)

Mike Marshall, California Angels outfielder (1991)

Anyone else worth nominating?

1 thought on “No. 41: Glenn Davis”