This is the latest post for an ongoing media project — SoCal Sports History 101: The Prime Numbers from 00 to 99 that Uniformly, Uniquely and Unapologetically Reveal The Narrative of Our Region’s Athletic Heritage. Pick a number and highlight an athlete — person, place or thing — most obviously connected to it by fame and fortune, someone who isn’t so obvious, and then take a deeper dive into the most interesting story tied to it. It’s a combination of star power, achievement, longevity, notoriety, and, above all, what makes that athlete so Southern California. Quirkiness and notoriety factor in. And it should open itself to more discussion and debate — which is what sports is best at doing.

The most obvious choices for No. 89:

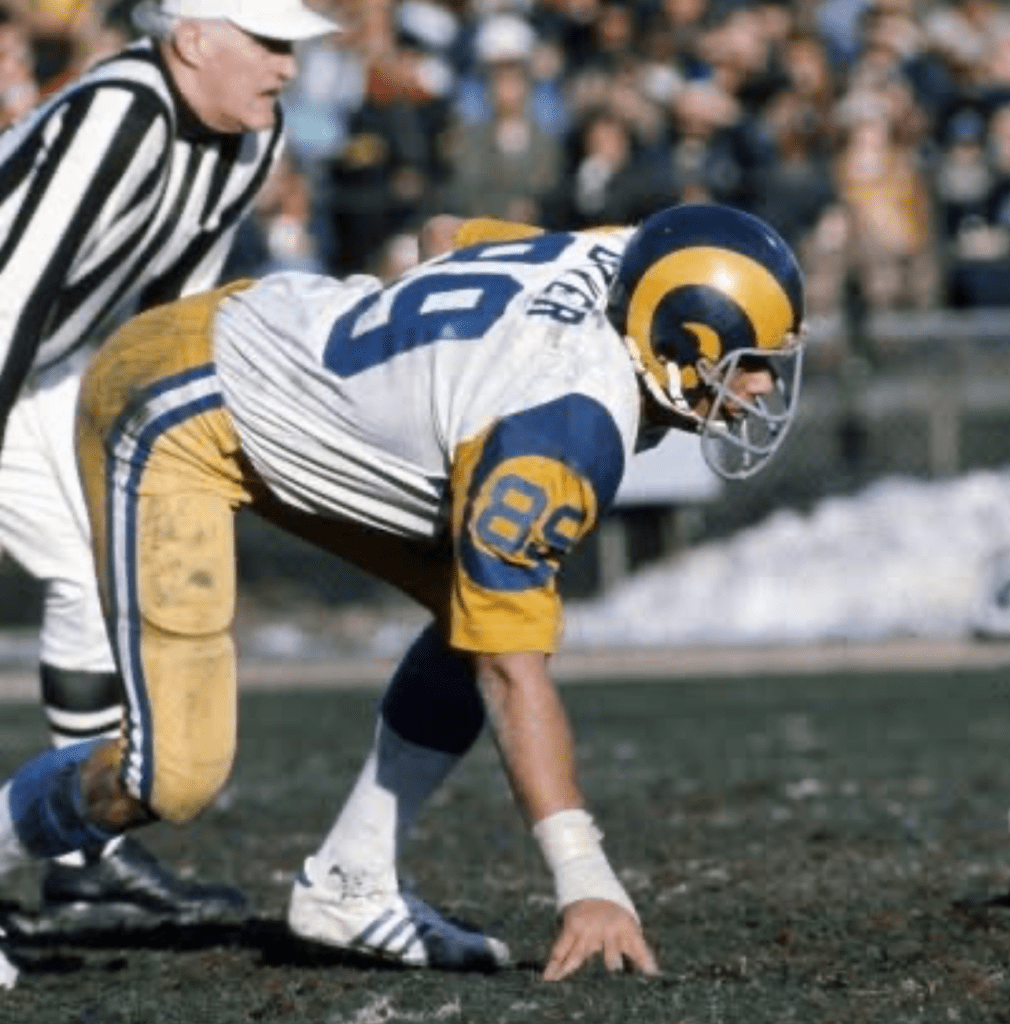

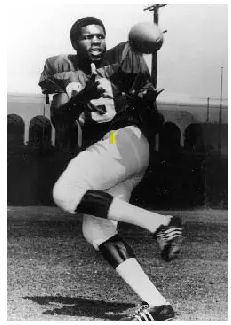

= Fred Dryer, Los Angeles Rams

= Ron Brown, Los Angeles Rams

= Charles Young, USC football

The not so obvious choice for No. 89:

= Jack Bighead, Pepperdine football

= Bobby Jenks, Los Angeles Angels

The most interesting story for No. 89:

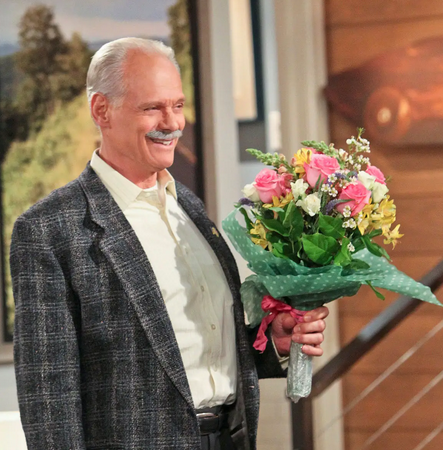

Fred Dryer: Los Angeles Rams defensive end (1972 to 1981) via Lawndale High and El Camino College

Southern California map pinpoints:

Hawthorne, Lawndale, Torrance, L.A. Coliseum, Long Beach, Hollywood

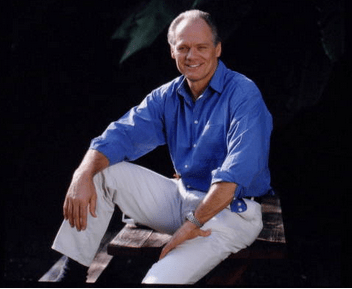

Whatever version of Fred Dryer first comes to mind — the swift-moving Los Angeles Rams’ defensive end sideswiping an offensive tackle en rout to hunting down another quarterback, or a guy named “Hunter,” a fearless LAPD private who bent the rules when necessary as a TV character — there was always that underpinning of “Dirty Harry” in motion.

Dryer had a job and a duty to perform it. In both cases. Vengeance could be a motivational tactic. He cleaned up messes, no matter how dirty or harry it became.

A day in court never seemed to bother him, either. Justice had to be serviced, whether Dryer was pushing back on a contract dispute as either a professional athlete or a popular thespian. Dryer pulled those levers of justice, his modus operandi, with or without a legal need to produce a habeas corpus.

There was a point at the height of his TV fame, almost a decade since the official end of his NFL career, when Dryer found himself in a huddle of entertainment industry writers. They soft-tossed him questions about how, as he was about to turn 42, he best self-identified at this point in his life.

Dryer tackled it all head on.

A headline in the Chicago Tribune seemed to make it clear: “Fred Dryer, Actor, Gives His Past A Punt.” It went on to explain:

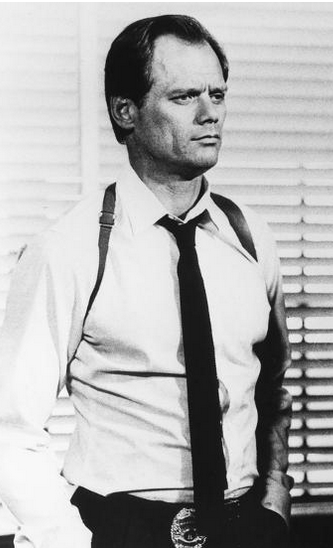

“As the hard-boiled Rick Hunter, a Los Angeles homicide detective, Dryer projects an image that combines Steve McQueen’s rough sexiness with Clint Eastwood’s stoic demeanor. And Hunter shows just about as much respect for his suspects Constitutional rights as Eastwood’s Dirty Harry does.

“Dryer has a theory about why his acting career took off when so many of his colleagues’ fizzled.

“ ‘Most athletes fail at it because they don`t understand that when you come from a success in another area like sports, you have to leave the sports world behind. You have to kill the guy that made you a sports star and start over completely.

“Fred Dryer, football player, is dead. I put him away and started with this other guy.

“That means you don’t bring the ego you had in football with you. Without mentioning names, I see ex-football players who are just not willing to let go of (their athlete image), because if they lose that, who are they? You have to let go of your past before you gain something else.”

Dryer was just staying in character. And considering he almost had the role of Sam Malone when the iconic TV series “Cheers” launched years earlier, the thought of hanging around a bar known as an ex-jock just wasn’t his idea of being pro active.

Born in Hawthorne in 1946, and growing up on a chicken farm in Lawndale, Fred Dryer thought his life as an athlete would be as a hard-throwing baseball pitcher. At Lawndale High, he also threw the shot put and discus on the track team.

He grew to be tired of the baseball players he hung around with. The football guys were more to his liking. The story goes he ended up playing football for two years at nearby El Camino College in Torrance not because he wasn’t recruited, but it’s where his football pals went for drinks after hitting the beach. A coach asked him to try out there. It led to Dryer not only becoming the school’s athlete of the year in 1966, making the JC All-American team, but he would be part of the inaugural ECC Athletic Hall of Fame in 1988, along with Keith Erickson and George Foster.

Two seasons at Division I-AA San Diego State came as a result of being recruited by the Aztecs’ defensive coordinator John Madden. The 6-foot-6 defensive end who may have weighed 200 pounds wore No. 77 play on Don Coryell teams that went a combined 19-1. Voted the school’s outstanding defensive lineman on a squad that included future NFL player/actor Carl Weathers, Dryer “had great speed, a hurtling slashing style that earned him a spot on the Little All-America team of 1968,” as was noted in his 1997 bio for induction into the College Football Hall of Fame.

The advantage he had playing in the East-West Shrine Game, the Hula Bowl and the 1969 College All-Star Game led to becoming the New York Giants’ first-round pick, No. 13 overall, in the 1969 NFL Draft. Dryer started 42 straight games as right defensive end and recorded 29 sacks — still not an official stat in the NFL.

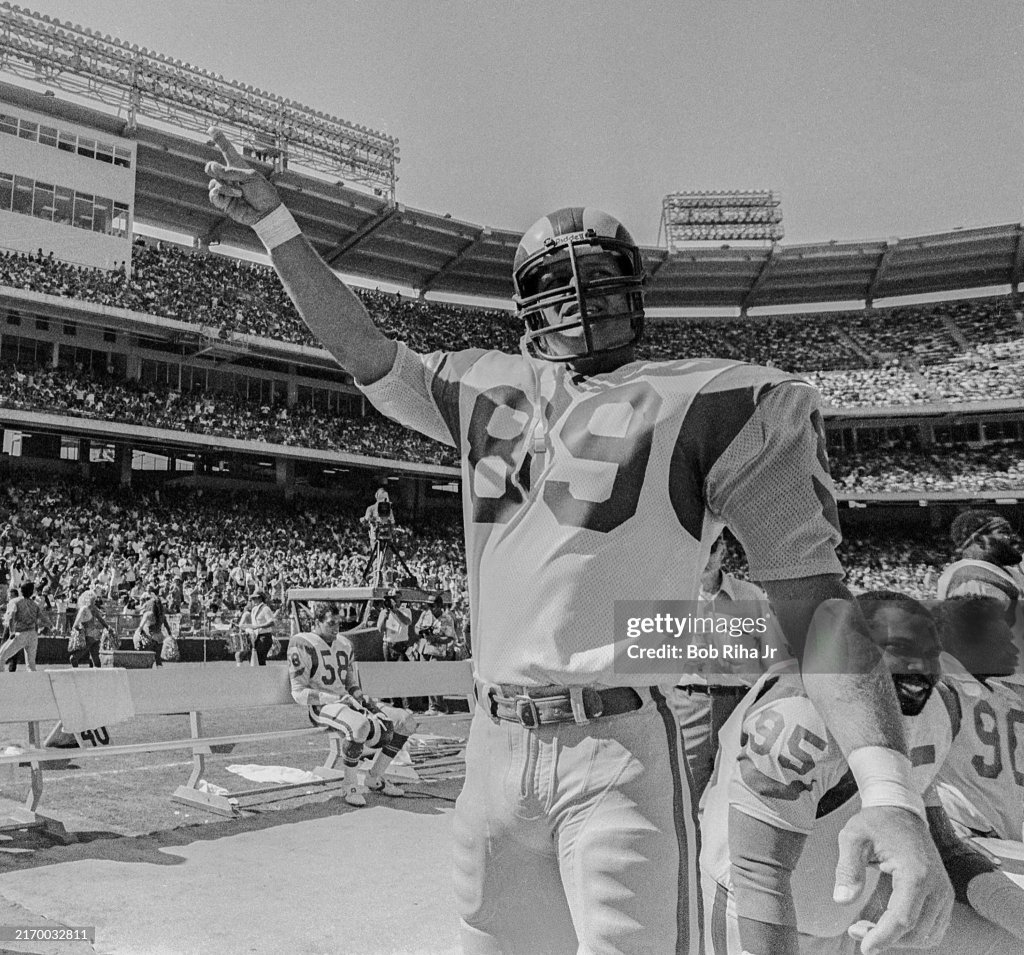

Run-ins with the Giants management over his contract, where he had a second-team All-NFC season, became an issue. Dryer would be a free agent if the team didn’t sign him before the 1971 season. So they tried to trade him. He went to New England for three draft picks. Dryer refused to report unless they made him the highest-paid DL in the league. The Patriots sent him to the Los Angeles Rams for a ’73 first-round draft pick — which would become USC fullback Sam Cunningham, its franchise all-time leading rusher.

As columnist Dave Klein wrote for the Newark (N.J.) Star-Ledger in April of ’72:

“Fred Dryer, the tallest hippie in the world, finally got what he wanted. … Fearless Fred wanted … the opportunity to play on the West Coast, where he was born, raised, educated and where his ties (meaning — surf boards, beach buggies and Volkswagen campers) are deepest. … So Dryer, who always carries his toothbrush and who sewed the curtains for his camper, will become a fulltime beach boy. He’ll probably prosper and flourish in the sun of southern California, and grow up to be a great ulcer of the New York Giants.”

Writer Murray Olderman also put down in ink: “The tweeze of vanity is not in his strut now. He was something special those first three years in pro football. He’s just another body on the roster of the Los Angeles Rams these days. And he’s learning. Things about defense he was never aware of. The total effect on Fred Dryer is nonentity.

“I’m just another guy here,” he says. “I just want to be left alone.”

Dryer had already arrived at the team’s Long Beach training came with a Greta Garbo attitude.

By this point, he had also figured out ways to embellish his resume.

“When he was with the Rams, they listed him at 230, 235 (pounds), but Fred still weighed 225,” insisted Maddon, who never got to coach Dryer at San Diego State, leaving in 1967 to join Al Davis’ staff with the Oakland Raiders for the start of his legendary pro career. “So, whenever they were gonna weigh him, he’d tuck a little five-pound weight under each armpit, and then wear a T-shirt, and the scale would read 235. He was never over 225 in the pros, and when I saw him the other night, he was still as skinny as he was at (San Diego) State.”

Dryer didn’t actually live in his van as many thought, but was with his mom in an apartment complex he bought in Long Beach. But he didn’t correct the narrative of how he lived. It made for a better story. He accepted a backup role to Jack Youngblood on the left side of the line. Even while playing with a broken hand and nose, Dryer recorded 4 ½ sacks to go with 40 tackles that first year in L.A.

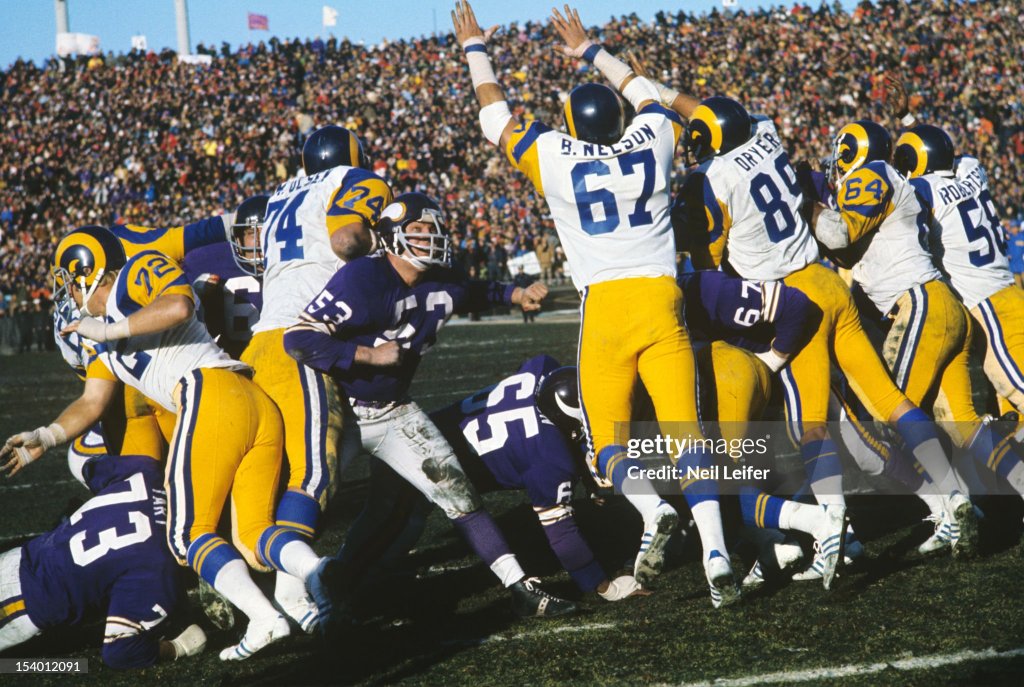

Dryer started all 14 games of the 1973 season, and the Rams went 12-2 to win the NFC West with Chuck Knox as the head coach. Ray Malavasi was the defensive coordinator who put in a 4-3 alignment, with Dryer, Larry Brooks, Merlin Olsen and Youngblood as the latest “Fearsome Foursome” sequel.

In a Week 6 win at the L.A. Coliseum against Green Bay, Dryer set an NFL record not likely to be broken — not just two safeties in the same game, but they came on back-to-back possessions in the fourth quarter. To cap off a 24-7 win that would improve the Rams to 6-0, Dryer chased down Packers starting quarterback Scott Hunter on a 12-yard sack in the end zone, and did the same to his backup, Jim Del Gazio, to account for the Rams’ final four points.

“They really weren’t that complicated — guy drops back to pass, you run up the field, you run into him in the end zone,” Dryer explained years later. “That’s how I saw it. As they were running their offense, the quarterbacks keep dropping deeper and deeper. Well, hell, I just ran around the tackle. I couldn’t have ordered it up more perfectly.”

In 1974, Dryer and Youngblood each had a league-best 15 sacks, Dryer was voted the Rams’ Outstanding Defensive Lineman, and the team returned to the NFC title game. Still no Super payoff.

Dryer’s only Pro Bowl season came in ’75, a year where he scored his first and only touchdown on a 20-year fumble return during a 42-3 Monday night win in Philadelphia. After the game, Dryer promised that if he ever scored again he would set his hair on fire in the end zone.

After that season, Rams owner Carroll Rosenbloom gave Dryer a five-year, no-cut, no-trade, no-waive, permanent roster-spot contract. In return for that guarantee — somewhat unheard of at that time — Dryer signed for considerably less money than he could have gotten elsewhere. Dryer would later say he lost about $700,000 over the course of the five years because he wanted that security.

Year after year, Dryer’s ability to hang quarterbacks out to dry was testament to his ability as someone who used his speed to his advantage, as well as and alignment that allowed him the freedom to navigate the backfield.

At age 33, Dryer had become the oldest member of a 1979 Rams squad that limped to the NFC West title at 9-7, pulled off a 9-0 win over Tampa Bay in the NFC title game, and then earned the right to face Pittsburgh in a Super Bowl game played at the Rose Bowl, giving the Rams its first SoCal homefield advantage. That season, Dryer again started every game, but split time with Reggie Doss. Still, Dryer recorded a career-best five sacks in one game, for losses of 49 yards, while making Phil Simms’ live miserable in a Week 9 loss to the New York Giants.

His nine QB sacks was the second-best individual performance on the ’79 Rams. It is noted that from 1974 to 1979, as the Rams played in five of six NFC Championship games, its defense gave up the fewest points, fewest yards and piled up the most sacks than any other in the league.

“Ray Malavasi put in a tremendous defense — he happened to be a defensive line coach — and everything started with the defensive line to control the line of scrimmage,” Dryer explained. “Ray said: We won’t sit in an even front and let the center off the line of scrimmage. I didn’t want anyone down blocking me. I would stud the tight end on his outside shoulder. I was a wizard when it came to convincing people I should be on a tight end down block.”

By starting all 16 games in 1980, he had 118 consecutive starts with the Rams and 174 games in a row as a pro. Dryer signed another deal with the team, and GM Don Klosterman gave him all the same contract provisions that Rosenbloom had before — except Rosenbloom was no longer the owner. He had mysteriously died. His wife, Georgia Frontiere was now in control of the purse strings.

When then-head coach Malavasi tried to cut Dryer during camp in 1981, Dryer kept showing up. He was actually cut twice.

Dryer wouldn’t leave. Look at the contract, he said.

The battle became so intense between Dryer and management, he acknowledged the fans chanting his name from the stands of Anaheim Stadium by blowing them kisses.

Frontiere even wondered if Dryer would agree to leave in exchange for having his number retired at halftime of the season opener. You couldn’t buy him off that easy.

“They plucked with the wrong guy,” said Dryer. “When Jesus Christ was hung on a cross, at least they had the decency to take him down. These people should be made to divest this franchise. They’re incompetent.”

As Dryer appeared in just two games in the 1981 season, the team cut him again in October. Dryer filed a $5 million suit against the franchise that November, claiming an additional “severe emotional distress” because of how he was let go. The suit went to trial in 1985 in California Supreme Court. It was finally settled.

“My whole life isn’t football,” Dryer said in 1981. “I have other interests — acting, television movies, TV series. But when you have a large part of you ripped away like that, it hurts. It really hurts. I’ll always be hurt over the way this whole thing was handled and money can’t fill the hole that’s in your heart.

“Ten years from now when I look back on my career I should be able to see the happy times. The good games, the championships, the Super Bowl in 1980. But I won’t see those moments. When I look back, this is what I’ll remember. The way they got rid of me. And that’s kind of sad.”

With 103 sacks — a total that again was not officially recognized until after he retired — Dryer had put himself in the top 30 all time of that category. As of 2025, he remains in the top 60 ahead of Hall of Famers such as Charles Haley, Alex Karras, Warren Sapp, Bob Lilly, Howie Long and, ahem, Merlin Olsen.

By then, Dryer felt he found a new career safety net.

The career transition

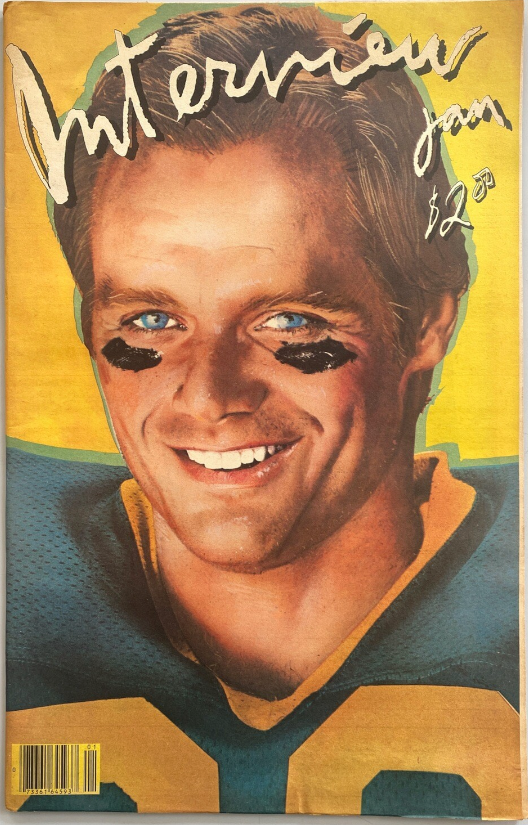

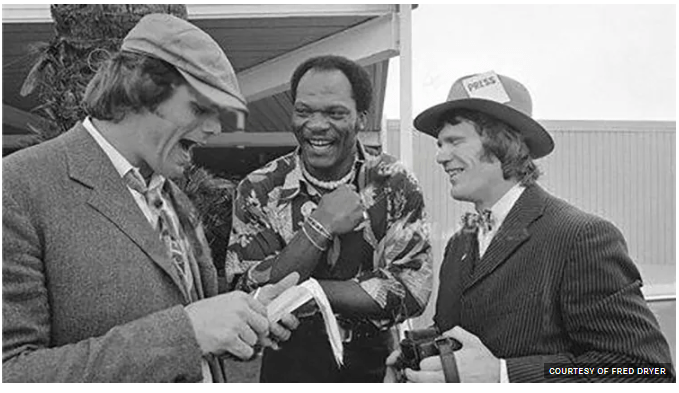

At the 1975 Super Bowl in New Orleans, Dryer got a taste of what it might be like as a dress-up actor.

He and Rams teammate Lance Rentzel went to a Hollywood costume shop, rented some old-time 1920s newspaper reporter tweet-coats and brimmed hats — inspired by the Jack Lemmon and Walter Matthau movie “The Front Page” — and talked Sport magazine editor Dick Schaap into letting them be part of the badgering/inquisitive media members tasked to cover the championship game between the Pittsburgh Steelers and Minnesota Vikings.

“I’d rather go to a funeral of an enemy than I would attend one of these things again,” Dryer, going by the name “Scoops Brannigan,” said as he recalled how that media day event all went down. “It was the most boring, full-of-shit group I’ve ever seen in my life.”

Already secure with a Screen Actors Guild card he obtained while an active NFL player, Dryer had already got some movie-set experience playing the role of a football player in the 1976 movie “Gus.”

He thought he might like becoming a color analyst with CBS’ NFL coverage in 1981 and ’82, but after about a dozen telecasts, he said he was tired of traveling and the restrictive nature of the job. The acting thing was interesting. He got his first credited role on TV’s “Laverne & Shirley,” and also had bit parts in “Lou Grant” and “CHiPS.” In 1981, he played Melanie Griffith’s stepfather in the made-for-TV movie “The Star Maker.” He also played a sergeant chasing down bad guys in “Cannonball Run II.”

At that time, NBC was workshoping a new sit-com called “Cheers,” and had been casting for the lead role of Sam Malone, the ex-athlete/bartender at a Boston pub where everyone knew each other’s names. Dryer went for it. So did William Devane. Ted Danson landed it.

Ken Levine, the longtime writer for “Cheers,” explained how that happened: “As originally conceived by the Charles Brothers, Sam Malone was a former football player for the Patriots. Fred Dryer was more who they had in mind. Ted was so charming and there was such chemistry with Shelley Long that they decided to cast him instead. But Ted as a football bruiser is only slightly more believable than me as an NFL lineman so they made Sam a baseball player instead.”

Dryer ended up appearing in a four early episodes of the show as a local TV sportscaster with a loud sports jacket named Dave Richards — a pal of Malone’s from their days at Boston Red Sox teammates.

In May of 1983, after Dryer married actress and Playboy centerfold Tracy Vaccaro, he was up for a new role on a detective show, “Miami Vice.” It turned out that at 6-foot-6, he was far too tall to play the role of James Crockett, which went to Don Johnson).

This was also an era of TV crime shows where rugged men were paired up with beautiful, hard-edged females. Think of “Moonlighting,” “Scarecrow and Mrs. King,” “Hart to Hart” and “Remington Steele.”

NBC had it sown version called “Hunter” in 1984.

As a rule-breaking L.A. Police Department plain-clothed homicide detective, Hunter would bust around town in a moss-green 1977 Dodge Monaco and lament at how the dark underbelly of the city needed to be fixed. If he broke the rules doing it, fine.

Dryer fit into the role playing off sergeant Dee Dee McCall (Stefanie Kramer). His “Dirty Harry” persona took hold.

“Nobody could throw a guy off a building like me,” Dryer said in a 2013 interview.

But Dryer almost didn’t last past the second season before the producers tried to throw him under the bus.

Before work started in 1986, Dryer threatened to quit unless he received a sizable boost from his $21,000 an episode fee. He noted that over on CBS’ “Miami Vice,” the show that rejected him, Don Johnson was making double his salary.

As “Hunter” producer Steve Cannell filed a $20 million breach-of-contract suit against Dryer in to L.A. Superior Court, the show was prepared to go on without him. Actor Joe Cortese was hired as Dryer’s replacement — Cortese would be either Hunter’s half-brother or cousin to keep the name alive in the story line. And he would get $30,000 an episode. There was already a script drafted for the first episode where Cortese and Kramer would work together to solve the disappearance of Dryer.

Dryer reappeared. Along with a deal that gave him $50,000 an episode.

Dryer explained that this attitude he had about standing firm on areements came from not enjoying how his father once treated him.

“My father wouldn’t be clear with me,” he said. “He was always trying to tell me what to do. I didn’t like it from him. I didn’t like it from coaches or owners and I don’t like it from anyone now.”

By the sixth season, Dryer was elevated to executive producer. A new female co-lead (Darlanne Fluegel as officer Joanne Molenski) appeared in the seventh season, but she had “creative differences” with Dryer. Halfway into that season, she wanted out, so her character was written off in a murder. Dryer could arrange such a thing.

In a 1985 interview, Dryer sized up how the world of a pro sports athlete could prepare some for a life as a Hollywood actor: “The discipline, the interaction, the necessity to think on your feet, the preparation, the imagination to free lance and interpret within the framework of a team concept. And in both businesses, all people see is the glamour end of it. They don’t see the hard work that goes into the finished product.”

An NBC vice president of casting also said at the time: “Athletes bring with them a certain name value, a personality and a presence. People are generally curious about them. Also since television is visual medium, it helps that your typical jock is a ‘hunk.’ Mike Warren, for example, is adorable. Fred Williamson is a handsome man. Fred Dryer is very good looking.”

In 1985, when a TV critic described Dryer as someone “made up of equal parts of Clint Eastwood and Richard Widmark, with a soupcon of Henry Fonda,” Dryer still laughed at one review of his work that said: “He moved from the NFL’s defensive line to the very front line of TV offensiveness.”

He shot back: “For every athlete who tries to act, there are 100 who don’t make it.”

At a time when “Hunter” hit its peak in 1988, Dryer fully embraced what his role had become, and the comparisons that went with it.

“Fred Dryer is the ultimate American hero,” said Roy Huggins, the show’s one-time executive producer. “He’s an icon. He walks across the screen and you say, ‘Yeah, there goes another one.’ Another Gary Cooper, John Wayne, Clint Eastwood. I think Fred is an actor who just happened to play football.”

Dryer embellished: “There is no one who can replace Clint Eastwood. He’s one of my heroes along with John Wayne and Steve McQueen. I came up on those guys. If I could have one-tenth the success of Eastwood, I’d be happy.

“People watch television to see people. They want to see James Garner or Don Johnson or J. R. Ewing. NBC stuck with the show after that first season because they liked me. And once they put it in the right time slot, I became known to the viewers and my popularity and the popularity of the show just shot up.”

It was pointed out that Dryer had become one of the few former NFL players who figured out how to navigate the TV star role — like Olsen (“Little House on the Prairie”), Karras (“Webster”) or Ed Marinaro (“Hill St. Blues”).

“Bringing this dynamic athlete into the insurance or real estate business can work for you,” Dryer said. “But acting is different. You have to kill that football guy off because he can’t help you.

“The mistake a lot of athletes have made is they don’t get rid of that guy. They want to bring that successful football player to acting, and it screws up the technique. It blocks them from looking at the work clearly and becoming another character. They march that ego, their fame, their name right in there and they expect to be given work because they are famous football players.”

Asked if he lamented losing the role in “Cheers,” Dryer went on the defense, saying: “I could have played the hell out of Sam.” He then went deeper into how that rejection helped shape his career, making more analogies.

“(Humphrey) Bogart was romantic as well a tough guy. I do see myself continuing in action film roles, but I want to do comedies and romantic stuff too. I want to do ‘Out of Africas.’ I’m never going to be Hamlet. But do you think Lawrence Olivier could do what I do? Do you think he could kick down a door?”

The show lasted more than 150 episodes, lasing through 1991. It included a made-for-TV movie revival in 2003, which nearly led to the show returning as “Hunter: Back In Force.” It went into syndication and was translated into dozens of languages in more than one hundred countries. It even spawned an ABC parody show, “Sledge Hammer!,” launched in 1986 that at least gave singer Peter Gabriel a hit song.

Considering Dryer’s track record of lawsuits filed by him and against him, it may have fittingly been incorporated into a “Hunter” script. An episode on December of 1990 read: “Hunter (Fred Dryer) fights a lawsuit accusing of him a false arrest during his investigation of a series of robberies at automatic bank-teller machines.”

In 1991, Dryer joined former NBC executive Brandon Tartioff and went to Paramount Studios to start Fred Dryer Productions. That led to two NBC movies — “Day of Reckoning” in addition to “The Return of Hunter.” Two years later, Dryer landed notable roles as Mike Land in the TV series “Land’s End” as well as a police chief in “Diagnosis: Murder.”

In 1997, he was back in court. A jury awarded him a $2.5 million suit against his former employer, Skyvision Entertainment, for back payment on “Land’s End,” but it also said Dryer had to pay them $200,000 for cost overruns that he created.

In 2000, Dryer produced, directed and starred in a feature film, “Highway 395.” At this point, he had created his own road to success. Some of it paved with court papers.

The legacy

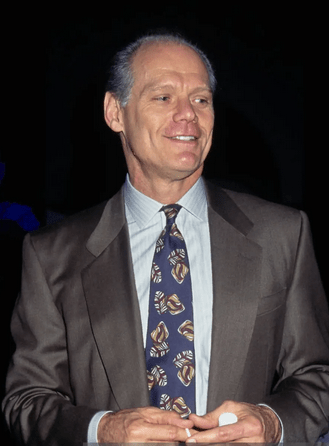

Dryer, who stayed put in Southern California to be near his daughter and three grandchildren, admitted in 2016 that he likely was dealing with CTE issues.

“I’ve had several concussions,” he said. “I was hospitalized with five of them. I know people that have been hit less times and have cognitive issues. I had head-to-head contact almost every day. For practice, I know that I took some damage. So, I know there’s a lot of people hurting.”

In 2009, his name was attached to a lawsuit against the NFL claiming his image in films and memorabilia to market the league was illegal without the league compensating him. It became a class-action suit. The league settled with 20 players, but Dryer opted out and a federal judge dismissed his case against NFL Films.

It never hurt that Dryer went all-in to create his action-hero pretense in Hollywood after all the physical stunting he dealt with playing for Hollywood’s NFL team.

In 2021, writer Ron Borges did a nifty job assessing how Dryer’s career could have been different if he had been a bigger-than-life figure in a more media-dynamic time period:

“If Fred Dryer were playing today, he would be an ESPN fixture, a social media darling and a human highlight reel on most NFL Sundays. At 6-6, he was a towering, blonde-haired, Hollywood handsome quarterback destroyer who also knew how to talk and loved to do it. But Dryer played primarily in the 1970s, when those things counted for a lot less than they do today, and so is remembered more for his post-playing career as an actor.

“Regardless of all that post-career success, Fred Dryer should be remembered for a lot more than acting. In his 13 seasons as a relentless pass rusher he amassed (enough sacks) that 40 years after his retirement he would tank … ahead of a number of Hall-of-Fame pass rushers.

“His arrival in Los Angeles was a testament to Dryer’s iconoclasm and his ability. His desire was to return to his native southern California because, as he once put it, ‘Everything is vertical in New York. I’m a horizontal person.’

“Widely considered among the top defensive linemen in the game for much of his career, he was better known as an iconoclast in a world of conservatives.

“Once during a heated moment late in a close game, one of his overwrought teammates said there ‘was no tomorrow.’ They had to win this game. Immediately Dryer walked away from the huddle and headed to the sidelines. One of his stunned teammates asked what was wrong. Dryer turned to them and said, ‘Nothing, but if there’s no tomorrow I’m not going to waste my last day playing football.’

“His teammates laughed, he returned to the huddle and the Rams won. That was Fred Dryer in a nutshell, a winner with a sense of humor.

“(By) throwing quarterbacks onto the ground a lot more frequently than most of his peers, did he do that often enough to be enshrined in the Pro Football Hall of Fame? Not as of yet. But when you top 100 sacks and start every game for 11 of the first 12 years of your career, you most definitely have a strong case.”

At the very least, the Rams might reconsider that number retirement thing. Of the eight that have been put away in the Rams’ franchise history, No. 89 is not among them. More than a dozen players have worn it since, most recently the well-heeled tight end Tyler Higbee.

Sounds like someone needs to do a little more investigating into this matter and perhaps break some rules.

Who else wore No. 89 in SoCal sports history? Make a case for:

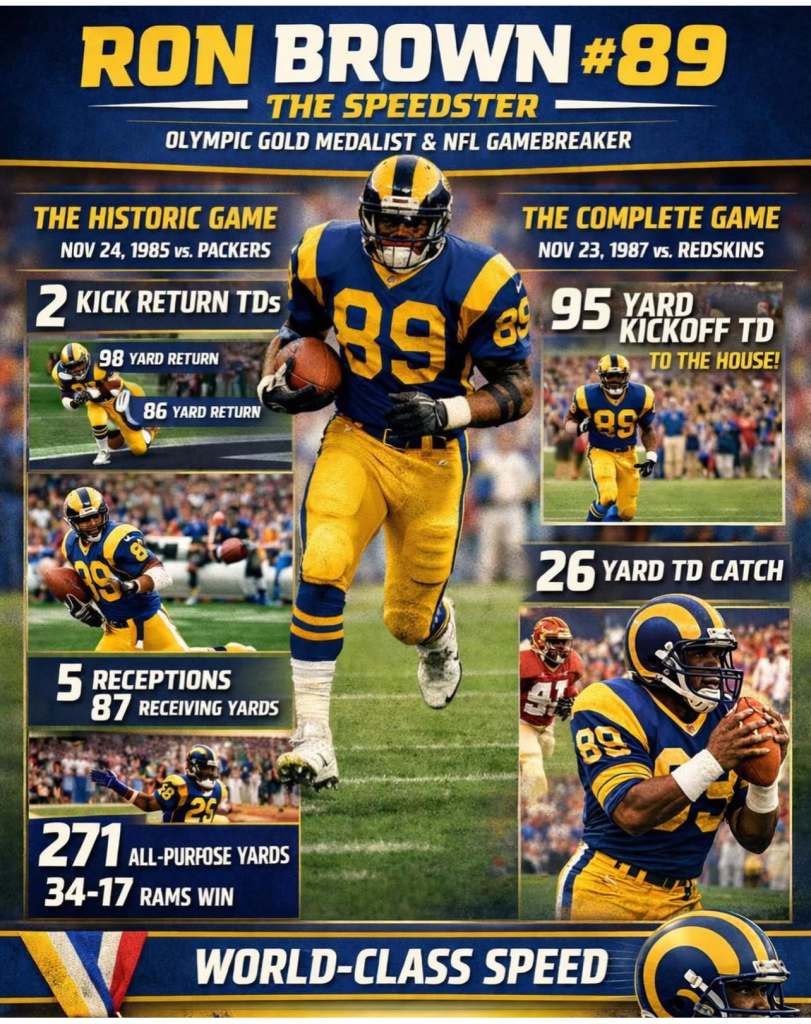

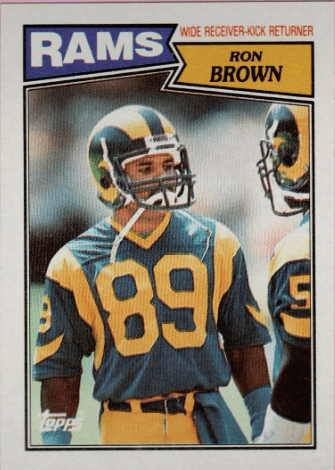

Ron Brown, Los Angeles Rams wide receiver / kick returner (1984 to 1991):

A year before he became the Rams’ 1985 Pro Bowl selection, Brown, born and raised in Baldwin Park, won a gold medal at Summer Olympics in Los Angeles at the Coliseum, running the second leg of the 400 meter relay in a world record time of 37.83 seconds. He also competed in the 60-, 100- and 200-meters. Originally picked by Cleveland in the NFL Draft out of Arizona State in 1983, Brown didn’t report because he was focused on the Olympics. After the Games, the Rams worked out a trade and got him his first six NFL seasons. After he caught 23 passes for 478 yards with four touchdowns as a rookie, the team discovered it was best served having him return kicks. In ’85, he had 28 returns for 918 yards for three touchdowns (the later two categories led the NFL) to earn Pro Bowl and All-Pro honors. After a brief stop with the Los Angles Raiders in 1990, Brown returned to the Rams for one last season, sporing No. 81. In his eight NFL seasons, he recorded 1,000 all-purpose yards four times.

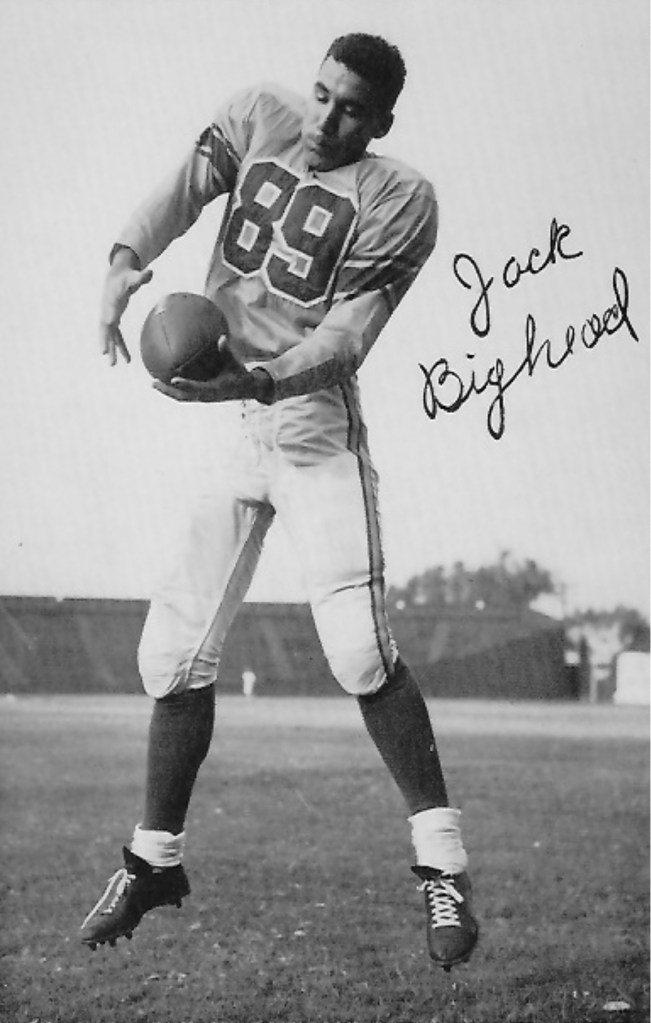

Jack Bighead, Pepperdine football end (1949 to 1951):

A 1981 inductee into the Pepperdine Athletic Hall of Fame, Bighead was a 6-foot-3, 215-pound Yuchi Indian from Oklahoma who first starred at L.A. Poly High. He earned Little All American honors at Pepperdine and held the program’s career records for receptions (86) and receiving yardage (1,261). After serving in the Navy during the Korean War, he returned to Pepperdine and set school records in the 440 and 220 hurdles in 1954. He played two years in the NFL, first with Baltimore (wearing No. 80) and his last with the hometown Rams in 1955 as he wore No. 86. That was the year he also got his Pepperdine degree and started a teaching career in Orange County.

Have you heard this story:?

Charle Young, USC football tight end (1970 to 1972):

A 2004 addition to the College Football Hall of Fame, Young was nicknamed “Tree” for his 6-foot-4, 234-pound frame. He became a unanimous first-team All-America as a senior when the 12-0 Trojans won the Rose Bowl and were crowned national champions. His 62 receptions set a career record for tight ends at USC to go with 1,008 receiving yards and 10 touchdowns. The sixth overall pick in the ’73 NFL draft by Philadelphia, Young was a four-time All Pro. His 13-year NFL career also included three seasons with the Los Angeles Rams (wearing No. 86).

And as for his name, spelled “Charle”?

USC officially lists it as Charles. But he once explained in 1982: ”People had a problem. They thought they had better call me ‘Charlie’ or “Chuck.’ But Chuck doesn’t fit me. And they didn’t know if they should spell the other one ‘Charlie’ or ‘Charley.’ So I decided to find a shorter name that would make it easier for them. I decided on ‘Charle.’ Call me Charlie if you want, but spell it ‘Charle’.”

Bobby Jenks, Los Angeles Angels minor-league pitcher (2000 to 2004):

A variety of baseball cards from Jenks’ early minor-league career with the Anaheim Angels made it seem as if the right-hander drafted out of Mission Hills would be a star once he harnessed his fastball. It never happened with the franchise. As the MLB game program for the 2024 Dodgers-Yankees World Series point out in a section dedicated to October memories from “unlikely heroes,” it explained Jenks’ contribution to the Chicago White Sox’ 2005 title run:

If, in April 2005, you made a list of the pitchers most likely to be standing victoriously on the mound at the end of that year’s World Series, White Sox reliever Jenks would have ranked about number 1,000. Jenks had pitches clocked as fast as 102 mph in the Angels’ minor league system after being drafted in the fifth round of 2000. Trouble was, that was also the speed at which he lived his life. There was no party Jenks wasn’t the life of, and no rule he wouldn’t break. In December, 2004, the Angels, tired of the headaches, let the White Sox claim him off waivers. To his credit, Jenks used that as a wake-up call. He blazed quickly through the minor leagues and was the Sox’s closer by mid-September. Earning a pair of saves in the ALDS, he dominated the Astros in the 2005 World Series. Jenks saved two of the four games against Houston and pitched two scoreless innings in another.

Jenks lasted seven MLB seasons, a two-time AL All Star, and posting five straight years with at least 27 saves. He did in July of 2025 at age 44. Mark Whicker posted this upon Jenks’ passing under the headline: “The pitching was the easy part for Bobby Jenks.”

We also have:

Nate Shaw, USC football defensive back (1964 to 1966)

Jim O’Bradovich, USC football tight end (1973 to 1974)

Norm Andersen, UCLA football wide receiver (1973 to 1975)

Hoby Brenner, USC football tight end (1978 to 1980)

Jonny Deluca, Los Angeles Dodgers outfielder (2023)

Anyone else worth nominating?

1 thought on “No. 89: Fred Dryer”