This is the latest post for an ongoing media project — SoCal Sports History 101: The Prime Numbers from 00 to 99 that Uniformly, Uniquely and Unapologetically Reveal The Narrative of Our Region’s Athletic Heritage. Pick a number and highlight an athlete — person, place or thing — most obviously connected to it by fame and fortune, someone who isn’t so obvious, and then take a deeper dive into the most interesting story tied to it. It’s a combination of star power, achievement, longevity, notoriety, and, above all, what makes that athlete so Southern California. Quirkiness and notoriety factor in. And it should open itself to more discussion and debate — which is what sports is best at doing.

The most obvious choices for No. 53:

= Don Drysdale, Los Angeles Dodgers

= Keith Erickson, UCLA basketball

= Rod Martin, Los Angeles Raiders

The not-so-obvious choices for No. 53:

= Jim Youngblood, Los Angeles Rams

= Lynn Shackleford, UCLA basketball

The most interesting story for No. 53:

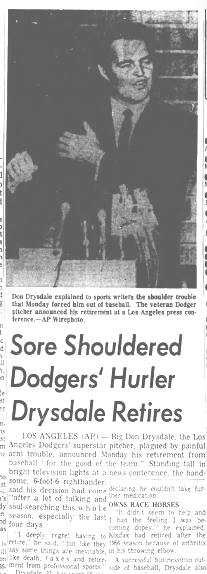

Don Drysdale, Los Angeles Dodgers pitcher (1958 to 1969), California Angels broadcaster (1973 to 1981), Los Angeles Rams broadcaster (1973 to 1976), Los Angeles Dodgers broadcaster (1988 to 1993)

Southern California map pinpoints:

Van Nuys, Bakersfield, Hollywood, Los Angeles (Coliseum, Dodger Stadium), Anaheim

The dogma of Don Drysdale presents itself as an expanded truth-or-double-dog-dare discussion of the “Big D” legacy.

No question it covers Southern California culture, as well as pop culture, and the culture of a Hall of Fame athletic and broadcast career.

There are bigger-than-life discoveries about the 6-foot-6 right-handed sidewinder, a San Fernando Valley-grown kid who spent all 14 years of his big-league career with the Dodgers organization and circled back for his final six years on the planet broadcasting their games:

Truth that’s been told: Don Drysdale led the league in putting the “mean” in what constituted a meaningful pitch.

Dare to discover: The dastardly stat was never kept, but if some SABR-cat researcher was compelled to go back and confirm, we’d suspect there was enough evidence to confirm he threw more brushback/purpose pitches during his 14-year career, all with the Dodgers, the last dozen in Los Angeles, than anyone else in his era.

He did hit 154 opponents, which breaks down into leading the majors for four seasons and the National League a fifth time. That can be interpreted from what Drysdale put out as his stated philosophy: You knock down/hit one of my guys, I knock down/hit two of yours.

The footnote to that: Why waste four pitches on an intentional walk with one pitch to the ribs will do? That line attributed to Drysdale may not take into the fact he did issue 123 IBB in his career.

Further research from Fangraphs on the essence of the “Two For One Special,” aka the “Drysdale Revenge Factor,’ shows of 18 times in his career where he hit two or more batters in a game. But deconstructing relative facts and figures from previous games and what else was happening is far more difficult to document. That mindset, however, leans into learning the art of intimidation by former veteran Brooklyn teammate Sal “The Barber” Maglie. Properly stated, it puts the idea in a batter’s mind that things could go south quick if you decided you owned the half of the 17-inch home plate that Drysdale decided was his for a particular at-bat.

“Batting against him is the same as making a date with the dentist,” Pittsburgh’s Dick Groat once said.

Added San Francisco’s Orlando Cepeda: “The trick against Drysdale is to hit him before he hits you.”

So, they knew the drill.

In a 1979 interview with the New York Times’ Dave Anderson, Drysdale said delivering the inside pitch was a “lost art” 10 years after his retirement.

“I just feel,” he was saying now, his right forefinger swirling the ice in his Scotch, “that when you’re pitching, part of the plate has to be yours. … The pitcher has to find out if the hitter is timid. And if the hitter is timid, he has to remind the hitter he’s timid.”

(Love that imagery).

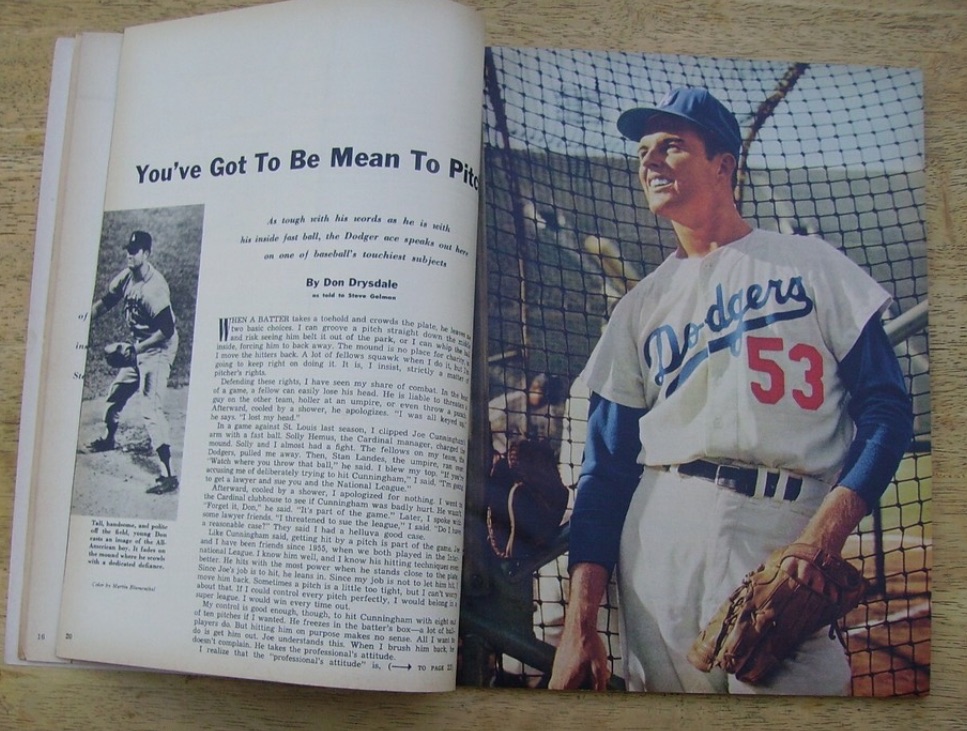

In that June 1960 Sport magazine story above, Drysdale put out there that while he pitched inside, he never deliberately threw at anyone.

“The mound is no place for charity, so I move the hitters back,” he said. “A lot of fellows squawk when I do this, but I’m going to keep right on doing it. It is strictly a matter of a pitcher’s right. My control is good enough (to hit a batter) with eight out of 10 pitches if I wanted. … But hitting him on purpose makes no sense. … All I want to do is get him out. (It) takes a professional’s attitude.”

In 1961, Drysdale was handed a five-game suspension and fined $100 by National League president Warren Giles for hitting Cincinnati’s Frank Robinson on the right forearm.

As Drysdale explained in his 1990 autobiography “Once A Bum, Always A Dodger,” he admits go having been warned by umpire Dusty Boggess already for pitching too tight to the Reds hitters.

The next time the Dodgers were in Cincinnati, where Giles had his office, Drysdale explained how he stopped at a bank and got $100 worth of pennies. He walked to Giles’ office, and placed the bag of them on the desk of Giles’ secretary and walked back to his hotel room, feeling proud of himself.

Giles’ office phoned him and asked him to come back for a visit. The conversation ended with Giles saying: “And by the way, I want you to take those pennies of yours and roll them back up for me.”

Drysdale spent the next few hours cursing and rolling pennies.

Truth that’s been told: Don Drysdale was a perennial Cy Young Award candidate en route to his 1984 Hall of Fame induction.

Dare to discover: Drysdale won the Cy Young Award just once, in 1962, during the Dodgers’ first season at Dodger Stadium, posting an MLB-best 25 wins, 232 strike outs and 314 1/3 innings pitched, to go with 19 complete games and a 2.83 ERA. He collected 14 of the 20 votes (a 70 percent share). He was also fifth in the NL MVP voting.

But 1962 was the only season Drysdale received any Cy Young votes for someone who had a record-tying five staring pitching assignments for the National League in nine All-Star games.

From its creation in 1956 through the 1966 season, the Cy Young Award was given to the best pitcher in all of baseball. Dodgers teammate Sandy Koufax won it three times in that 11-year period. But the 20 voters had just one vote. It was not a first-, second-, third-place ballot actually used then in the league’s MVP weighted-vote tallying. That changed in 1970. Since 2010, the Cy Young ballot now has room for five players to be ranked.

In 1968, after Drysdale started the July 9 MLB All Star game a month after he set the consecutive scoreless innings streak of 58 2/3 innings and threw six straight shutouts, all 20 NL Cy Young votes went to Bob Gibson (1.12 ERA and 13 shutouts, which also bested Drysdale’s total of eight).

The Year of the Pitcher was not an easy one to claim victory over. Even when Drysdale had the congratulatory backing of Democratic presidential hopeful Robert F. Kennedy, who mentioned Drysdale’s 5-0 win over Pittsburgh at Dodger Stadium to get him his scoreless inning streak on June 4, ’68 to 64 innings by pitching his sixth complete-game shutout. Kennedy had won the California primary and gave his victory speech at the Ambassador Hotel in Los Angeles just moments before he would be assassinated. Drysdale was said to have carried a cassette tape of Kennedy’s remarks with him. Drysdale extended the record four days later on June 8 through four more innings against Philadelphia, on the day of Kennedy’s funeral. Drysdale and his teammates wore a black armband on their sleeve in Kennedy’s honor.

In 1965, when Drysdale went 23-12 with a 2.77 ERA, Koufax was the unanimous 20-vote Cy Young winner (26-8, 2.04 ERA and an MLB record 382 strikeouts) and second in the NL MVP voting. Drysdale got himself another fifth-place spot in the NL MVP tally.

Which re-emphasizes the point: More voters put Drysdale on MVP ballots over his career than on Cy Young Award ballots.

Truth that’s been told: Don Drysdale was the most feared Dodgers’ hitter on their 1965 World Series title team.

Dare to discover: During the Dodgers’ 97-65 regular season run, do-it-yourself Drysdale, on the days he pitched, was often the only batter in the Dodgers’ regular lineup with a .300 batting average. He hit a two-run homer on Opening Day ’65 in the fourth inning that gave him a cushion in a 6-1 complete-game win over the Mets. After going 2-for-3 in a June 15, 2-1 home loss to San Francisco, Drysdale’s average was at a season-high .356. He finished 39 for 130 by the end of the season to level out at .300. His seventh and last homer of the season came off Houston’s Robin Roberts, a two-run homer in the third that gave the Dodgers a 2-0 lead en route to a 5-2 win, in which Drysdale won his 19th game.

On a team where Rookie-of-the-Year winner Jim Lefebvre and Lou Johnson tied for the team lead with 12 homers, Drysdale’s seven in more than half the at-bats looked pretty spiffy. Drysdale, who had 18 runs scored and 19 RBIs, didn’t get a Silver Slugger Award (they weren’t a thing at the time), but it fits into the narrative that a pitcher who could hit was a vital weapon — which explains why he’d despise the Designated Hitter rule for many reasons that came three years after his retirement but he had to confront as a broadcaster with the California Angels.

Along with his .508 slugging percentage and .839 OPS, Drysdale easily outdistanced the team averages of .245/.335/.657. With anyone who had 100-or-more at bats, Drysdale’s .300 was the best. His 2.2 offensive WAR was better than all but four Dodger batters (team-leader Maury Wills was 5.2, hitting .286 in 711 at bats, with an MLB-best 94 stolen bases). Drysdale had a 5.8 WAR as a career hitter (29 homers, 113 RBIs, .186 average in more than 1,300 plate appearances).

In 1965, Drysdale went 3-for-12 as a pinch hitter with a couple of RBIs. He hit as high as sixth in the Dodgers’ lineup at times. In the 1965 World Series, after Drysdale was knocked out of a Game 1 loss in the third inning, he came back in Game 2 to pinch hit for Koufax in the top of the seventh with the Dodgers trailing 2-1. Drysdale struck out against Mudcat Grant with runners on second and third.

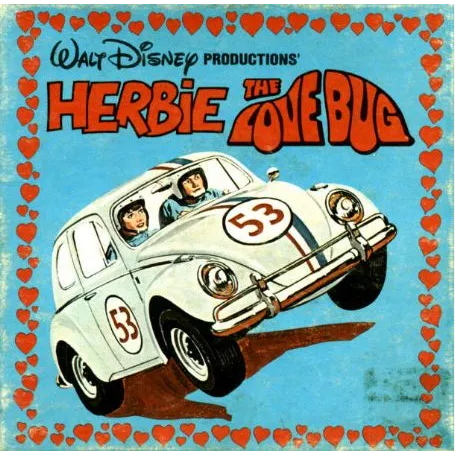

Truth that’s been told: Don Drysdale the reason why, in the iconic Disney film, “The Love Bug,” the Volkswagen Beetle nicknamed “Herbie” sports a No. 53 sticker on the hood, and the doors and on the engine hatch in the back, as he races with a mind of his own.

Dare to discover: It has been written many times in many places that “Love Bug” producer Bill Walsh, a longtime Disney employee, was indeed a Dodger fan, especially a Drysdale fan, and that was his creative decision for the film, which was being made during that ’68 season when was Drysdale setting the MLB record with 58 consecutive scoreless innings.

Sidenote: In 1986, pitcher Greg Matthews came up with the St. Louis Cardinals and asked for No. 53. To honor Drysdale? Nope. The left-hander out of Savanna High in Anaheim who just made it with Cal State Fullerton to the 1984 College World Series said it was because he was a fan of Herbie. “We’re both used to getting out of a lot of tough jams,” Matthews is quoted in the 2006 book, “Best By Numbers: Who Wore What … with Distinction” by The Sporting News.

Truth that’s been told: Don Drysdale and Robert Redford were Van Nuys High baseball teammates in the 1950s.

Dare to discover: Eh, no. But Drysdale loved the idea of it.

In his own 1990 autobiography, “Once A Bum, Always A Dodger,” Drysdale was more “The Natural” than Redford would be playing Roy Hobbs decades later.

“We were in the same grade, though I can’t lie to you and say that he and I were bosom buddies,” Drysdale writes. “I don’t remember him ever expressing an interesting in being a movie star any more than I was focused on being a baseball player.”

That’s the extent of what Drysdale said about it.

But when Drysdale’s died in 1993, the Los Angeles Times’ Steve Henson’s tribute recalled how friends remember him saying: “Oh, you mean Bobby; he was a pretty good first basemen.” Even though Drysdale knew Redford never played together.

“As far as I know, Redford never picked up a glove,” said Jim Heffer, a classmate of Drysdale and Redford. “I think Don covered for him, which showed the kind of gentleman he was.”

Redford, born in Santa Monica, appears to have played tennis at Van Nuys High. He did own a glove apparently. He was apparently a walk-on at the University of Colorado based on a tryout and told he might get a part-scholarship if he made the team. But he dropped out of school and went into acting. That seemed to pay off, naturally.

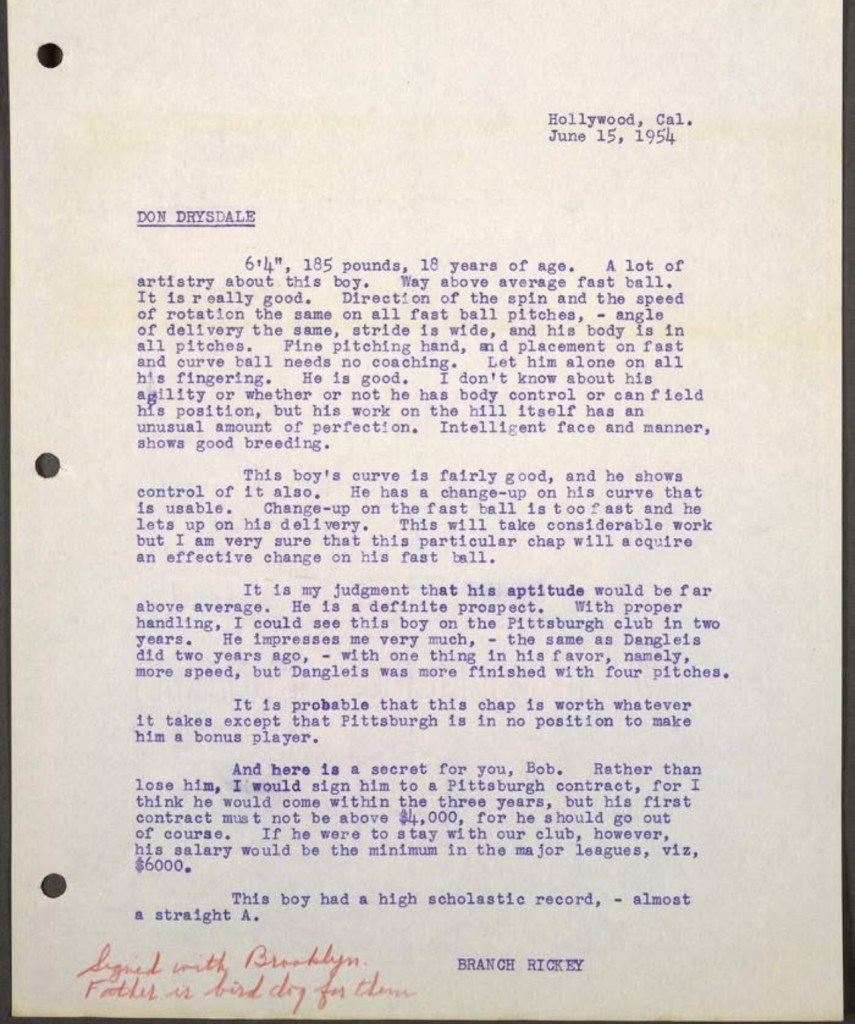

Truth that’s been told: Branch Rickey signed Drysdale to his first contract.

Dare to discover: No, but Rickey tried to pirate him.

The cigar-comping GM who famously signed Jackie Robinson to his 1947 contract with Brooklyn’s Dodgers and picked him to break the MLB color barrier in 1947, had moved onto to become the Pittsburgh Pirates GM when he scouted Drysdale at Van Nuys High.

Rickey wrote the report above and offered a $6,000 deal. Everyone else, including the Dodgers, were willing to give up $2,000. But Rickey’s plan for Drysdale started with him at their Triple-A Pacific Coast League affiliate, the Hollywood Stars, because the money offered made Drysdale a “bonus baby” and required the team to promote him faster. Rickey was then likely to move Drysdale down to a lower minor-league teams to give him more time to develop and eventually come up to the majors.

“If you’re not going to get a lot of money — and $2,000 isn’t a lot of money — then why not go where you have the best chance to learn?” Drysdale remembers his dad telling him.

That would be with Brooklyn, which dispatched him to its Class-C Bakersfield team. Drysdale was still in the big leagues by 1956, and pitching in a World Series after just turning 19.

Truth that’s been told: Drysdale is in the Labor Movement Hall of Fame.

Dare to discover: There is no Labor Movement Hall of Fame, but if there was, this essay by Pete Dreier in The Nation convinces us there should be. With Drysdale in it.

In order to form a more perfect MLB labor union, Drysdale and Koufax held a very visible 32-day contract holdout prior to the 1966 season. Ginger Drysdale, Don’s wife, a member of the Screen Actors Guild, suggested that they join forces. “If (Dodgers GM) Buzzie (Bavasi) is going to compare the two of you, why don’t you just walk in there together?” she proposed.

Koufax gave Drysdale permission to negotiate for both. The Dodgers agreed to pay Koufax $125,000 and Drysdale $110,000. Koufax objected. “I thought we’re supposed to get the same thing,” he said. But Drysdale—who had a wife and daughter—didn’t think he could hold out indefinitely and was willing to accept the lower amount.

They didn’t get the three-year contract or the salaries they sought, but they showed other players that the owners weren’t invincible in the face of collective action.

Truth that’s been told: Don Drysdale could carry a tune and was a professional recording artist.

Dare to discover: You be the judge:

Truth that’s been told: When Drysdale married Ann Meyers on the first day of November in 1986, what made that even more unique than a matrimony of Southern California star athletes was it was the first time that a married couple were members of their respective sports’ Hall of Fame.

Dare to discover: It worked because, after 10 years of falling short of the 75 percent of writers’ votes needed, Drysdale finally got into Cooperstown.

Meyers, our link to No. 15 in our SoCal Sports History 101 project, was a 1985 inducted into the International Women’s Sports Hall of Fame. She was later inducted into the Naismith Basketball Hall of Fame in 1993 as the first woman honored.

She met Drysdale appropriately when she appeared as a competitor and he was a broadcaster on ABC’s “The Superstars” made-for-TV competition, which took place in the Bahamas.

She thought he was Don Meredith, the former NFL quarterback part of ABC’s “Monday Night Football” team. Her Midwestern mother was more enamored with meeting Bob Uecker, another part of the ABC telecast, because she was so familiar with him as the Milwaukee Brewers’ broadcaster.

“The one thing I always remember when I first met Don is that he was such a gentleman,” Meyers once said in an interview. “And the one thing that I always loved, because I was from a big family, was just how these other guys responded to Donnie. You can go down the list with Duke Snider and Sandy Koufax and Bob Uecker and Pee Wee Reese and Ted Williams and Mickey Mantle — they were his brothers. But there was something that set Donnie apart. He was like this beacon. They were just all attracted to him. And believe me, all of those men were great in their own right. But there was something special about Donnie.”

Don just turned 50 and Anne was 31 when they married.

They had three children — Don Jr., born on his father’s birthday in 1987 as Don was broadcasting for the Chicago White Sox. Son Darren came two years later after Don joined the Dodgers’ broadcast team.

Daughter Drew arrived in March of 1993. Don Drysdale died four months later, while on a road trip with the Dodgers in Montreal. He was 56.

In Mark Whicker’s 2025 book, “Up And In: The Life of a Dodgers Legend,” time and time again Drysdale was referred to by family and friends as “a man’s man.”

During an appearance on Larry Mantle’s “Air Talk” on LAist/KPCC 89.3 FM, Whicker surmised that Drysdale was drawn to people like him who didn’t take themselves seriously, but were very serious about particular things that they saw not up to standards.

“I think he was a unique personality and all those who were with him saw him as a great leader,” said Whicker. “They may have respected and appreciated Koufax, but Don was more connected to how the team functioned, grabbing a six-pack, sitting on the team bus and telling stories. Very opinionated on and off the air. A strong ethic about how the game was played.”

Truth be told, there isn’t a lot of mythos to the Drysdale documentation. An appearance on the TV show “To The Tell The Truth” in November of 1959 has this glimpse.

The “affidavit” read on the show as the camera spanned the three men went this way: “I, Don Drysdale, am a pitcher for the Los Angeles Dodgers baseball team. This past season in which the Dodgers won both the National League pennant and the World Series, I led both leagues in strike outs and was voted the Most Valuable Player in the first All Star game. Last month, I started my career as a cowboy actor when I played a top feature role in the Western series, ‘Lawman.’ Signed, Don Drysdale.”

The panel easily picked him out from an encyclopedia salesman and in-coming U.S. service man in a cowboy hat — who men who the show’s producers rounded up mostly because they were also tall. The fact Drysdale himself wore a Dodgers’ uniform and cap also seemed to make it easier to believe him for who he was.

But anyone with a TV set who saw him just months before that ’59 season, appearing with his new wife of 2 ½ months, Ginger, on Groucho Marx’s “You Bet Your Life” show that also taped in Hollywood, could have separated him from any potential imposter.

“You’re a local boy, aren’t cha, Don?” Groucho asked.

“That’s right, Groucho, was born and raised in Van Nuys,” he replied.

“Where’s that?” Groucho followed up.

“That’s across the hills,” Drysdale responded, tilting his head back to the left, “over there in the San Fernando Valley.”

Asked if Drysdale if had any plans after his playing days were over, he seemed to have already figured it out: “Well, Groucho, I’d like to get into some sort of phase of radio or television work having to do with sports. I like talking, a sports program or something like that.”

“Tell me about Ginger, is she a good cook?” asked Groucho.

Long pause.

“No,” says Drysdale, pursing his lips and shaking his head with a smile.

Ginger almost snaps.

“Well, that’s Drysdale for you — another wild pitch,” says Groucho as the audience laughs.

The fact that Drysdale didn’t take himself too seriously and made him relatable could be found in all sorts of TV appearances.

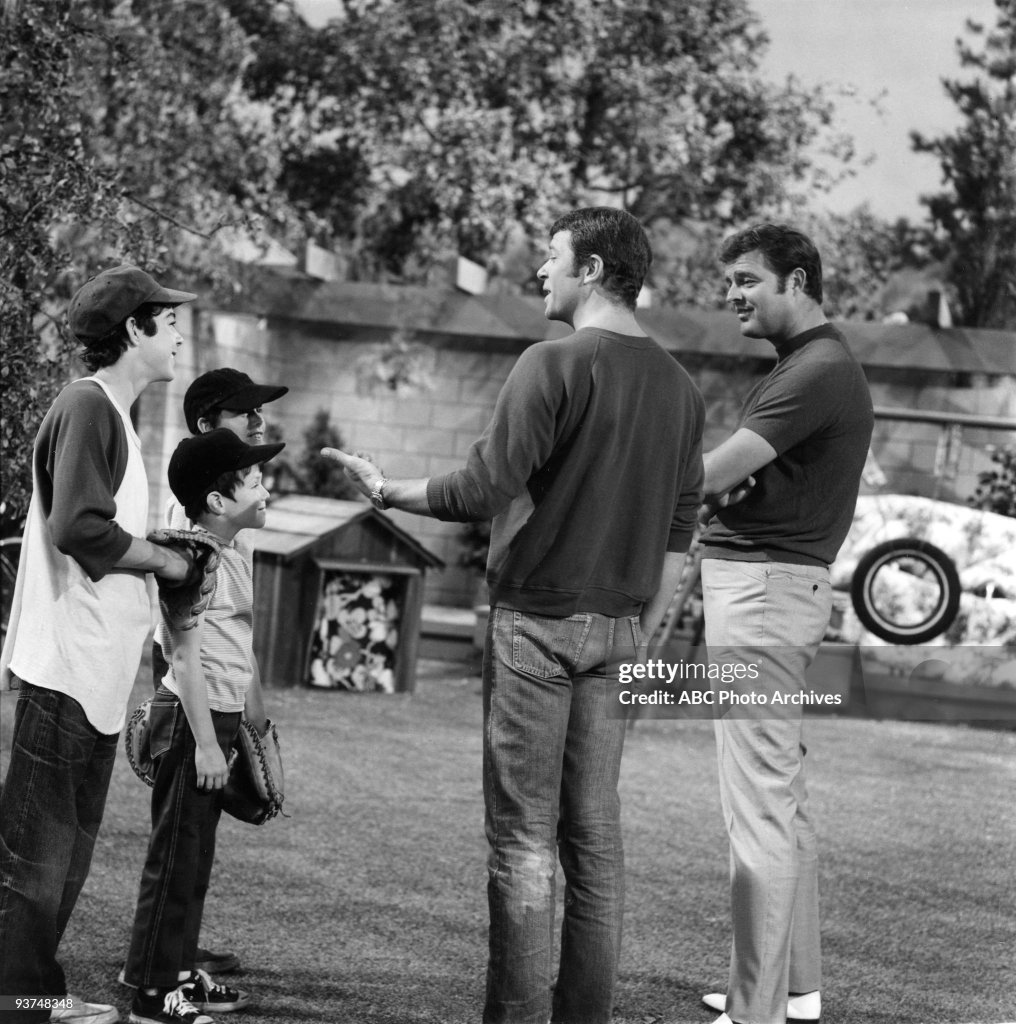

Like the commercial for Vitalis hair tonic, playing off the suspicions that he loaded baseballs with greasy fingers.

Kids in the ’60s always thought there could be a chance meeting with Drysdale. He appeared as himself on “Leave It To Beaver” (the Beaver just called him up in the Dodgers’ clubhouse) or “The Donna Reed Show” (her son had him as a coach) or, after his pitching days were over, on “The Brady Bunch” (he just showed up at the house with lessons to pass on). Drysdale also played himself in “Lucas Tanner” and “The Greatest American Hero.”

His acting chops were put to a test in roles for “The Rifleman,” “The Millionaire,” “The Flying Nun,” and “Then Came Bronson.”

Movie roles came as well and could be used as leverage in a contract dispute, as Drysdale and Koufax discovered before the 1966 season. That followed a trend for almost anyone associated with the Dodgers to get into the Hollywood scene if that was to their liking.

He had his own “Dugout” restaurant in Van Nuys, on Oxnard Street, as well as one in Anaheim. He had another place in Hawaii called “Club 53,” on the Big Island of Kona, and “The Whalers Pub” in Lahaina in Maui.

He owned race horses, and Willie Shoemaker won aboard one of his thoroughbreds.

All of that branding access and cultural connection was as a residue of a baseball career that saw him pitch in nine All-Star games, five World Series (three of them winners) and leading the NL three times in strike outs.

Drysdale never thought of himself as a baseball player, let alone a pitcher, growing up in the idealistic San Fernando Valley.

Between his junior and senior year of high school, Drysdale found himself more as a second baseman, first baseman and emergency catcher on the Van Nuys Post 193 American Legion team. The squad was coached by his dad, Scotty — who had a brief career as a pitcher in the Pacific Coast League’s Los Angeles Angels’ system in the 1930s and was now a repair supervisor for Pacific Telephone.

Roger Grabenstein, president of the Valley Ephebians high school honor society, is joined by classmates in a door-to-door campaign for passage of a school bond proposal on April 4, 1955. (Valley Times photo collection of the Los Angeles Public Libary archives)

One day, the team’s best pitcher, Roger Grabenstein, didn’t show up.

“I never gave pitching a thought,” Drysdale wrote in his autobiography. “My dad must have seen something in me. I remember him telling me that I wasn’t fast enough to play any position in the field other than catcher, and I don’t think he was too excited about me playing there. Dad had seen me throw casually during batting practice or playing catch, so he gave me the ball. All he told me was, ‘Don’t get cute and throw strikes.’”

Drysdale beat the North Hollywood team with a complete game.

Scott Drysdale saw Goldie Holt, a Dodgers scout sitting in the stands, and introduced them. Holt asked if he could see Don pitch for him a couple days later.

“If I threw 100 pitches, there must have been 85 strikes,” Drysdale recalled. “Everything clicked. I had no idea what was going on.”

That led him to playing on what was called a Brooklyn Dodgers Junior team, which at that time included future Dodgers pitcher Larry Sherry and his brother Norm, a catcher. There was also a scrapping infielder named George Anderson, better known as Sparky. All three were out of Fairfax High in L.A. and would make it to the Dodgers’ Class-C team in Santa Barbara as teenagers.

Drysdale, who also played football but sat out his senior year because of a growth spurt that affected him, became an All-L.A. City pitcher as a senior with a 10-1 record, throwing a no-hitter against North Hollywood with 12 strikeouts in a 7-0 win — one walk away from a perfect game.

As the season ended and his high school graduation neared, Drysdale met with Babe Herman representing the New York Yankees, some star power who asked him to sign up. The Milwaukee Braves and Chicago White Sox wanted him.

Before the smoke cleared, Rickey was chomping on his unlit cigar, trying to have a say.

Drysdale’s loyalty to the Holt and the Dodgers led him to signing with Brooklyn, and the bonus of having him start with Class-C Bakersfield. The deal was made the week before his high school graduation at Otto’s Pink Pig on Van Nuys Blvd., in Sherman Oaks.

After a year at Triple-A Montreal, Drysdale made it to the big leagues as a 19-year-old in April of 1956.

In his first start, he pitched a complete-game 6-1 win in Philadelphia, with Roy Campanella as his catcher, and he got his first big-league hit.

The next year, he had a 17-win season in the Dodgers’ final year in Brooklyn.

Four years trying to figure out the confines of the L.A. Coliseum had mixed results for Drysdale — he played in three All-Star Games, had 13 shutouts and 57 wins against 50 losses and would average more than 40 starts in the 154-game seasons.

The Dodgers’ move to the new Dodger Stadium was a much better fit for Drysdale.

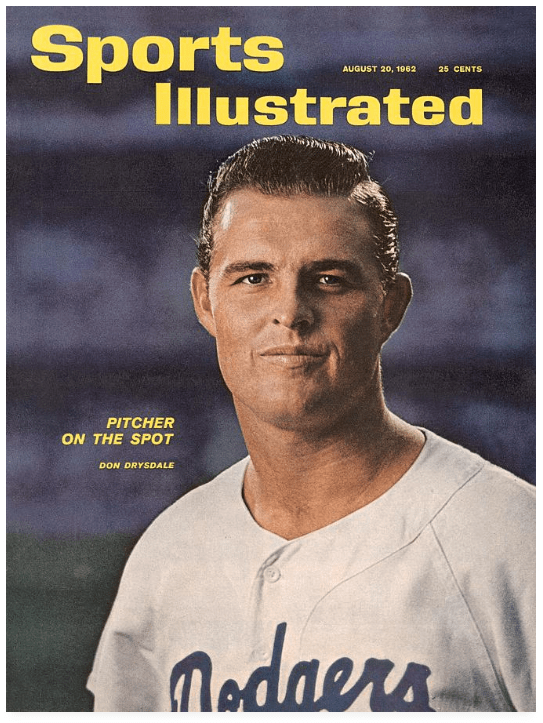

An August 1962 cover story on him in Sports Illustrated with the headline: “Pitcher On the Spot” revealed more about his career at that point in time. The story titled “Ex-Bad Boy’s Big Year” noted:

“Last week Drysdale’s throwing arm was as sound as his $35,000 paycheck (the most ever paid a Dodger pitcher). … Maturity and a fine opportunity to be the man of the hour have apparently hit Drysdale together. …

“Females make appreciative noises when observing his creamy good looks and his hair-tonic hairdo, and he is a made-in-Hollywood version of the boy next door. When not pitching, he is polite, relaxed and easygoing to a fare-thee-well, nurses no grudges and finds questions about his fabled temper tiresome in the extreme.

“ ‘I wish,’ he has said, ‘I could be like a milkman and be myself once in a while.’

“As himself, Drysdale is free of extravagant ideas and habits, and his tastes (Mexican food and western music) and pleasures (swimming and the sports page) are run of the mine. His only true interest, it appears, is playing baseball or capitalizing upon his fame in that game by endorsing male toilet articles and accepting bit parts in TV oaters. Well-fixed, you may believe, he lives in a $50,000 house and pool in Van Nuys with his wife and 3-year-old daughter, and his off-season work as a public relations man for an ice cream plant is well suited to him, since he tends to talk in slogans.

” ‘I give 100% when I pitch, and that’s all I can give,’ he may say, or ‘Baseball has been good to me,’ or, of course, ‘I couldn’t win without the other eight guys behind me.’

“The overall impression is that Drysdale is just barely three-dimensional, but as any Dodger will tell you, ‘He’s the nicest boy on the club’.”

In three of the next four seasons, the Dodgers would be in the World Series. Drysdale, who pitched the last two innings at Yankee Stadium in a Game 4 loss of the World Series, won Game 3 of the ’63 Series against New York (a 1-0 complete game victory) at Dodger Stadium and had a Game 4 win against Minnesota in the ’65 Series. He lost a 1-0 game to Baltimore in Game 4 of the ’66 Series.

After Koufax’s departure, and Maury Wills as well, the Dodgers dropped off significantly in 1967 to 73-89, eighth in the National League. Drysdale was the 30-year-old icon with 22-year-old Don Sutton, 23-year-old Bill Singer and 20-year-old Alan Foster trying to establish themselves. Drysdale and Osteen were the only two Dodgers in the ’67 All Star Game.

Then came ’68, where the Dodgers were still seventh in the NL (76-86). Drysdale would only post a 14-12 mark despite a 2.15 ERA.

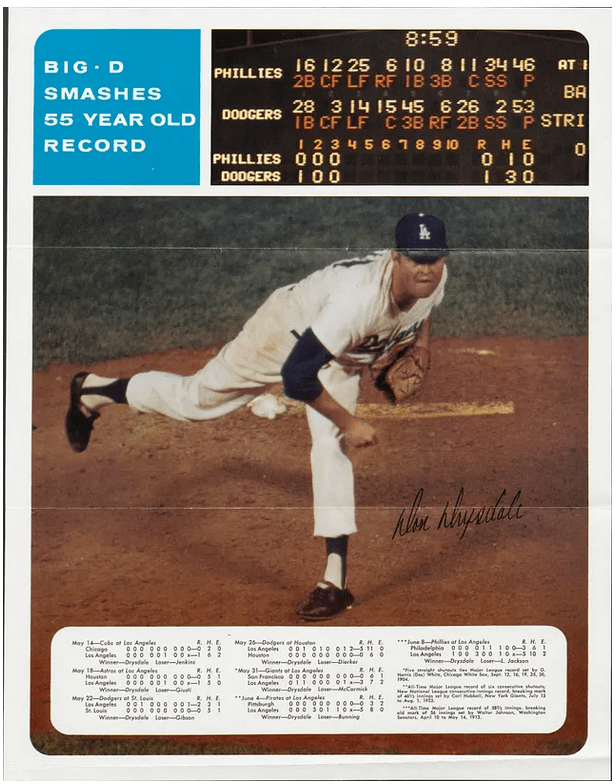

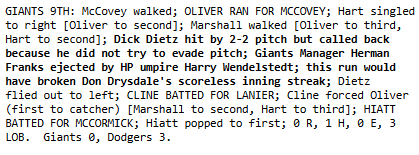

The ironic footnote to Drysdale’s 58 2/3 scoreless inning streak — featuring games where bested Chicago’s Ferguson Jenkins, Pittsburgh’s Dave Gusti, St. Louis’ Bob Gibson, Houston’s Larry Dierker, San Francisco’s Mike McCormick and Pittsburgh’s Jim Bunning, improving his record from 1-3 to eventually 8-3 — is was a hit batter could have ended his streak at 44 innings. But a judgment call of an umpire, Harry Wendlestdt, ultimately keep it going.

On May 31 in the ninth inning of a game at Dodger Stadium against the rival San Francisco Giants, Drysdale, nursing a 3–0 lead, loaded the bases with no outs. On a 2-2 count to Dick Dietz, catcher Jeff Torborg called for a slider. Drysdale’s pitch sailed inside and grazed Dietz’s elbow. He started to run to first, but Wendlestedt ruled that Dietz hadn’t tried to get out of the way of the pitch. The game was delayed some 25 minutes while Giants manager Herman Franks and third base coach Peanuts Lowery argued. Dietz, now on a 3-2 pitch and one away from a walk to force in a run, filed out to left, but not deep enough for a sacrifice fly.

Drysdale’s final career victory was on July 28,1969 when he had a complete-game shut out the San Diego Padres 19-0 in San Diego, his 49th career shutout. In his career, Drysdale posted one shutout for every four wins — 25 percent of the time. Drysdale drove in the final run of that game with a seventh-inning double after driving in their 16th run with a fifth-inning single.

At the time of his retirement, and somewhat anticlimactic in the aftermath of the “Great Holdout of 1966” with him and Sandy Koufax, Drysdale was the franchise leader in innings, shutouts and strikeouts.

In the current all-time Dodgers’ franchise record ledger, Drysdale remains second in innings pitched (3,432), games started (465) and shutouts (49); third in WAR for pitchers (61.4), wins (209), games pitched (518) and strike outs (2,486); and sixth in complete games (167).

And those 154 HBP numbers, the NL record at the time of his retirement, are most in Dodgers’ history, but, for what it’s worth, just No. 20 all time.

His 29 homers as a pitcher is a franchise-best and also No. 6 all-time in MLB history. Twice he had seasons of seven homers.

A torn rotator cuff in his right shoulder did him in during the 1969 season — just one year removed from his ’68 success. He just turned 33. He could only make 12 starts.

The broadcasting career could take its course, some of on ABC’s national MLB team with Howard Cosell as well as other Wide World of Sports assignments. In the span of 20-plus years, Drysdale spent nine with the California Angels as a partner to Dick Enberg, and his last seven with the Dodgers on a rotating roster for TV and radio with Vin Scully and Ross Porter.

Enberg, who died in 2017, once said to me: “Every day was a good day when you were with Don Drysdale,” and then threw in some classic off-color stories that wouldn’t be fit to print, comments Drysdale could make to him after he muted his mic. The Enberg/Drysdale partnership also lent it sent to several years as the Los Angeles Rams radio broadcast team.

Joining the Dodgers in 1988, fate brought Drysdale into Orel Hershiser’s orbit as Dodger No. 53 gave way to Dodger No. 55 to set a new record with 59 consecutive scoreless innings.

Drysdale was in the Dodgers’ visiting dugout in San Diego after Hershiser came off the field following 10 scoreless innings to break the mark. They shared a hug and did an interview live for radio and TV as the game continued.

“I really didn’t want to break it,” Hershiser said. “I wanted to stop at 58. I wanted me and Don to be together at the top. But the higher sources (manager Tommy Lasorda and pitching coach Ron Perranoski) told me they weren’t taking me out of the game, so I figured, what the heck, I might as well get the guy out.”

Drysdale laughed when told of Hershiser’s statement.

“I’d have kicked him right in the rear if I’d have known that,” Drysdale said. “I’d have told him to get his buns out there and get them.”

Later that month, Drysdale’s local Dodgers radio call of Kirk Gibson’s 1988 World Series Game 1 walk-off homer may be only the third most memorable after Vin Scully’s description for NBC TV and Jack Buck’s call on CBS Radio to the national audiences.

“Well, the crowd is on its feet and if there was ever a preface to ‘Casey at the Bat’ it would have to be the ninth inning. Two outs. The tying run aboard, the winning run at the plate, and Kirk Gibson, standing at the plate. Eckersley working out of the stretch, here’s the three-two pitch … and a drive hit to right field … way back! This ball is gone!”

After nearly two minutes of pure crowd noise, Drysdale resumes:

“This crowd will not stop. They can’t believe the ending! And this time, the Mighty Casey did not strike out! … The Dodges waiting for Gibson to limp around the bases were very careful as if they were touching a Rembrandt at home plate.”

The end for Drysdale came on a road trip to Montreal, the city where he played Triple A for the Dodges, and the place where his heart gave out on him.

Los Angeles’ heart was broken as well.

More Drysdale tales:

Growing up in Bakersfield in the ’50s and ’60s, George Culver wanted to be like Don Drysdale. In his autobiography, “The Earl of Oildale” Culver explains how as a Little Leaguer, he first saw Drysdale play in his hometown for the Class-C Bakersfield Indians.

Drysdale managed an 8-5 mark and 3.45 ERA in 14 starts, including 11 complete games. Culver, a star athlete at North High in Bakersfield and then at Bakersfield College, could also drive down to see Drysdale in person at the L.A. Coliseum and then Dodger Stadium.

By 1966, Culver reached the big leagues himself as a 22-year-old with Cleveland. By 1968, Culver was in the Cincinnati Reds’ rotation, en route to a career-high 226 innings in 35 starts.

Just a month after Drysdale set his MLB record streak with six straight shutouts, the Dodgers and Reds faced off on a Friday night in early July at Dodger Stadium. It was Drysdale vs. Culver.

“I was about to get a chance to not only pitch against him, but hit against him and that nasty side-arm deliver,” Culver wrote. “What a thrill (why me?)”

The game was scoreless through 10 innings — yet Drysdale and Culver were still pitching. Both gave up five hits. At the time, Drysdale may have been the Dodgers’ most feared batter in the lineup. Ken Boyer pinch hit for Drysdale in the bottom of the 10th and struck out — the last batter Culver faced. Culver came out for a pinch hitter in the top of the 11th-inning as 23-year-old Don Sutton came on in relief of Drysdale. The Reds won, 2-0, on Lee May’s run-run double in the 12th inning.

It was a split decision in Drysdale vs. Culver — actually, a no-decision for both.

“This was, without a doubt, the best game I ever pitched in the major leagues,” wrote Culver, who four starts later tossed a no-hitter against the Phillies at Connie Mack Stadium.

In 1998, a CBS “60 Minutes” crew was about to do a profile on Ila Borders, the Whittier native who became the first female to start a game as a pitcher in a men’s professional baseball league,

Cameras tried to follow her every move as she was preparing for her start with the Duluth-Super Dukes of the Northern League.

In the prologue of her 2017 book, “Making My Pitch: A Woman’s Baseball Odyssey,” Borders wrote about how having to retreat to the women’s restroom at the ballpark and put her feet up so no one could detect she was in the stall. She wasn’t all about just smiling and being cute for the cameras.

“I’m an athlete here to win,” she wrote. “Now get the hell out of my face. Would you tell a guy to smile? Growing up I heard about Don Drysdale … I was crazy about Drysdale, who everyone said was the nicest guy around — except for the days he pitched. Then no one went near him. … I’ve been fighting for this since I was ten years old.”

By the time Mike Wallace had the chance to sit down with her, Borders couldn’t really fight her way out of the whole thing. She told Wallace: “I’ve always had this fierce spirit to do what I want to do.”

Borders was born six years after Drysdale retired.

When Drysdale retired after the 1969 season, his No. 53 was given to young outfielder Tom Paciorek to wear for eight games in September of 1970.

The next year, Paciorek was re-issued No. 17. And No. 53 was never seen again, finally and officially retired in 1984 when Drysdale went into the Baseball Hall of Fame.

They are the only two to have ever worn it in the franchise’s history.

Who else wore No. 53 in SoCal sports history? Make a case for:

Rod Martin, Los Angeles Raiders linebacker (1982 to 1988):

Out of L.A.’s Hamilton High and two years of playing at L.A. City College, Martin wore No. 52 for two years USC. It was enough to entice the Oakland Raiders to make him a 12th-round pick, No. 317 overall, in the 1977 draft, considered, at 6-foot-2 and 218 pounds, too small for a linebacker and too slow for a safety. Did they know he’d make two Pro Bowls and be a key on two Super Bowl teams? He set a record with three interceptions in Super Bowl XV and made the cover of Sports Illustrated. He broke up a key third-down pass on the Raiders 7 yard line in the second quarter in Super Bowl XVIII, sacked Joe Theismann once, and tackled John Riggins for no gain on a fourth-and-one conversion on the last play of the third quarter, and then recovered a fumble in the fourth quarter.

Lynn Shackleford, UCLA basketball forward (1966-67 to 1968-69):

Out of Burroughs High in Burbank, where the 1965 CIF Southern Section Player of the Year averaged 25.6 points a game and also earned varsity letters in baseball and golf, the 6-foot-5 Shackelford started on three of coach John Wooden’s NCAA title teams that went 88-2 during his three varsity seasons in Westwood on a roster with Lew Alcindor and Lucius Allen. After a year in the ABA, he got into broadcasting and became Chick Hearn’s analyst for seven seasons on Los Angeles Lakers’ radio and TV. He was also the sports anchor on KHJ-TV Channel 9 in L.A. for five years. UCLA inducted him into its Athletic Hall of Fame in 2023.

Jim Youngblood, Los Angeles Rams linebacker (1973 to 1984): His only Pro Bowl year was during the Rams’ 1979 season and their run to Super Bowl XIV, when Youngblood had a career-best five interceptions, returning two for touchdowns. He had 14 picks (four returned for TDs) in his 12 seasons with the Rams, who took him in the second round of the 1973 NFL draft out of Tennessee Tech. He started 98 of his 152 games with the Rams.

Nate Landman, Los Angeles Rams linebacker (2025): The mike linebacker and on-field signal-caller set a franchise record with 17 total tackles in the Rams’ 17-3 win at Baltimore in Week 6 of the 2025 season. Born in Zimbabwea where his father played rugby, the All-Pac-12 Conference linebacker from Colorado signed a one-year, $1.1 million deal with the Rams before the 2025 season after three years in Atlanta. He was named a team captain and was the NFC Defensive Player of the Week in Week 10 with a 10-tackle game in a win over Houston. The Rams gave him a three-year, $22.5 million contract extension in the middle of the ’25 season.

Have you heard this story:

Keith Erickson: UCLA basketball forward (1962-63 to 1964-65):

The player who Bruins basketball coach John Wooden would call the finest athlete he ever coach emerged from El Segundo High and El Camino Junior College without a primary sport to attract any sort of recruitment. During his one year at ECC (1961-62), it helped that his coach was George Stanich, Wooden’s first All-American recruit who was also a multi-sport athlete. It also helped that the ECC team faced the UCLA freshman squad as part of its schedule.

Stanich and UCLA basketball assistant/chief recruiter Jerry Norman created a plan for Erickson in Westwood: Wooden would provide a half scholarship for him to be on the basketball team as a shooting forward and Art Reichle could have another half-scholarship for him to play baseball as a shortstop or center fielder. If Erickson didn’t make it in either sport, neither coach wouldn’t have spent a full scholarship spot on the proposition. But there was also a third choice: Volleyball. UCLA coach Al Scates wanted to at least see what the 6-foot-5 hitter could do, so he snuck Erickson onto his team for a tournament that took place during basketball season — despite a warning from Wooden that it would compromise Erickson’s status. While Erickson helped Wooden win his first two NCAA titles at UCLA in ’64 and ’65, most importantly as a defensive specialist in the full-court zone press and as a senior captain who made the All-Pac-12 team, he also helped Scates win his first title, the ’65 U.S. Volleyball Association championship. Turns out, Erickson played one season of baseball and made basketball his priority (with a fulltime scholarship), and volleyball second — which included his time on the U.S. Olympic volleyball team that in 1964 competed in Rome and then on the beach playing in pro tournaments.

Although he was drafted by the NBA’s San Francisco Warriors at age 21 in 1965, Erickson got to come back to Los Angeles and play for the Lakers from 1968-69 to 1972-73, including on their ’72 title team, wearing No. 24. His top game as a Lakers: 30 points, five rebounds and six assists in a win at Atlanta in January of 1969.

He was inducted into the UCLA Athletic Hall of Fame in 1986, the Pac-12 Hall of Fame in 2016, and the Beach Volleyball Hall of Fame in 1993.

We also have:

Bobby Abreu, Los Angeles Angels of Anaheim (2009 to 2012)

Brendan Donnelly, Anaheim Angels/Los Angeles Angels of Anaheim (2002 to 2006)

James Edwards, Los Angeles Clippers center (1991-92); Los Angeles Lakers center (1992-93 to 1993-94). Also wore No. 42 for Lakers in 1977-78.

Carlos Estevez, Los Angeles Angels pitcher (2023 to 2024)

Anyone else worth adding?

2 thoughts on “No. 53: Don Drysdale”