This is the latest post for an ongoing media project — SoCal Sports History 101: The Prime Numbers from 00 to 99 that Uniformly, Uniquely and Unapologetically Reveal The Narrative of Our Region’s Athletic Heritage. Pick a number and highlight an athlete — person, place or thing — most obviously connected to it by fame and fortune, someone who isn’t so obvious, and then take a deeper dive into the most interesting story tied to it. It’s a combination of star power, achievement, longevity, notoriety, and, above all, what makes that athlete so Southern California. Quirkiness factors in. And it should open itself to more discussion and debate — which is what sports is best at doing.

The most obvious choices for No. 94:

= Kenechi Udeze, USC football

= Paul Bergmann, UCLA football

= Mateen Bhaghani, UCLA football

The not-so-obvious choices for No. 94:

= Terry Crews, Los Angeles Rams

The most interesting story for No. 94:

Don Yi, Korean language interpreter for Chan Ho Park (1994)

Southern California map pinpoints:

Lakewood, Glendale, Los Angeles (Dodger Stadium)

The 1994 Major League Baseball season started with Don Yi wearing the No. 94 jersey for the Los Angeles Dodgers.

It wasn’t necessarily the Year of Yi in Dodgertown that particular season, but numerically, it made sense.

While Yi was neither bat boy, ball dude nor clubhouse attendant, the 31-year-old UCLA graduate and computer programmer spoke South Korean. The Dodgers in general, and Chan Ho Park, more specifically, could use Yi’s skill set.

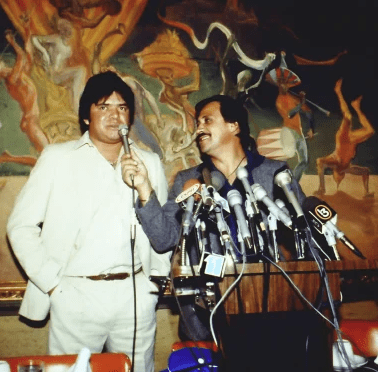

As an important part of a contract stipulation when the Dodgers signed a $1.2 million landmark deal with the 20-year-old pitcher, announced at a press conference at a hotel in Koreatown, the team would provide an interpreter.

Where Yi came into the picture, it’s somewhat a mystery.

Park, as the first MLB player brought in from South Korean player, needed to acclimate and assimilate. Yi was there to accomodate. This new-fangled job would evolve, or go sideways, on a daily basis.

It started with this: What is Park’s name?

The first time Yi was in full uniform as the team arrived its Vero Beach, Fla., training camp in March of ’94, reporters and teammates wanted to know what to call him.

“Some people are calling him Mr. Ho,” said Yi.

Dodgers broadcaster Ross Porter called him “Park Chan-ho,” as per Korean custom to use the family’s given surname first. Park asked if Yi could help him get the media covering him to “Americanize” his name.

Once that box was checked, what else might get found in translation?

Major League Baseball’s desire to add more players from the Far East to play in the U.S. led to the realization that a language barrier had to be properly addressed.

Latin American players could often find teammates, coaches and club officials who speak Spanish. Even managers who worked in the Winter Leagues in the Dominican Republic picked up key words and phrases that were useful. When Fernando Valenzuela came up with the Dodgers in 1981, Spanish-language broadcaster Jaime Jarrin became as visual a presence with the media scrums helping to translate Valenzuela’s responses to his remarkable performance as a rookie.

Players from Japan, Korea or China rarely had that option for the first few decades of global player movement.

Park, for what it’s worth, said he heard Spanish spoken nearly as frequently as English when he arrived to with the Dodgers. English was a language he’d been working on hard to learn, but it was more than that as he missed the privacy he had in his former life in Gongju, some 70 miles south of Seoul in the providence of South Chungcheongnam-do.

Since 2016, all MLB teams were required to have at least two full-time Spanish language interpreters, paid by the team, purely as a working relationship. Yet Asian players were often on their own, or the team tried its best to accommodate without any formal process.

The San Francisco Giants had the first Japanese pitcher on its roster — Masanori “Mashi” Murakami, a 20-year-old reliever from 1964 to ’65. He started in Single-A Fresno where a sizeable Japanese American community existed. Two other teammates came with him from the Nankai Hawks of the Japanese Pacific League.

“The frustration [with the language barrier] manifested in his play on the field,” said Bill Staples Jr., the chairman of SABR’s Asian Baseball Committee. “You can see it in the box score. Two passed balls in one game, then another, then another.”

Murakami made history, but he found it more comfortable to return to Japan to play for another 17 seasons.

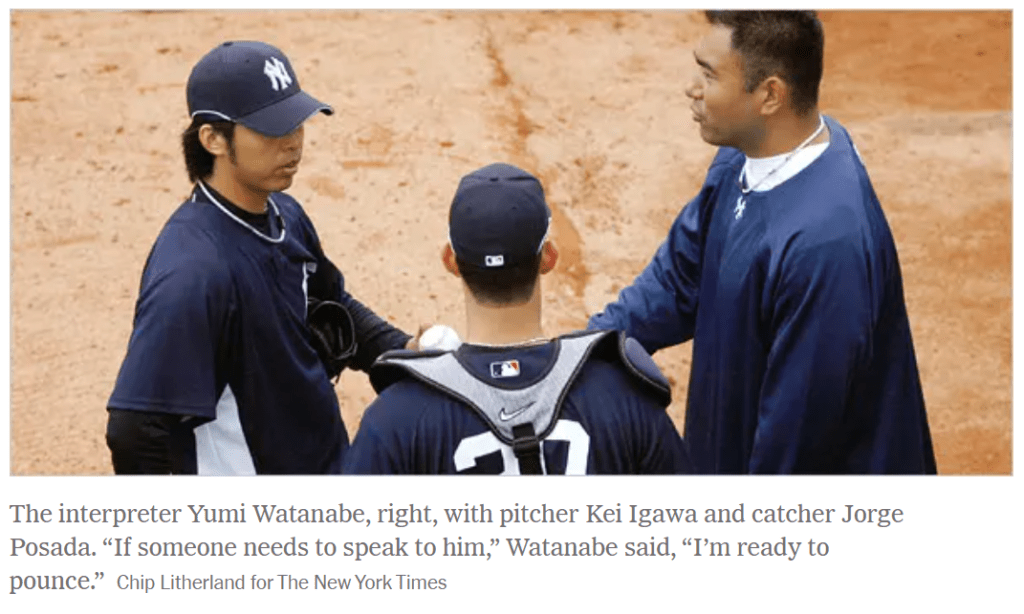

A 2007 story in the New York Times was one of the first to take an expanded look at just how MLB team-hired interpreters fit as a normal thing within team culture. The New York Yankees had been spending about $300,000 on the salaries and expenses for interpreters that year, plus having a Japanese news media adviser on the payroll. Compare that to what the MLB player’s minimum salary that year of $380,000, up from $327,000 the previous season.

By 2007, the Dodgers were deep into international players rotating in and out of the roster. That season, there were pitchers Hung-Chih Kuo and Chin-Hui Tsaso (both from Taiwan) and Takashi Saito (Japan). They also had shortstop Chin-lung Hu (Taiwan), which led to the culmination of a long-awaited line for broadcasters to use: “Hu’s on first.”

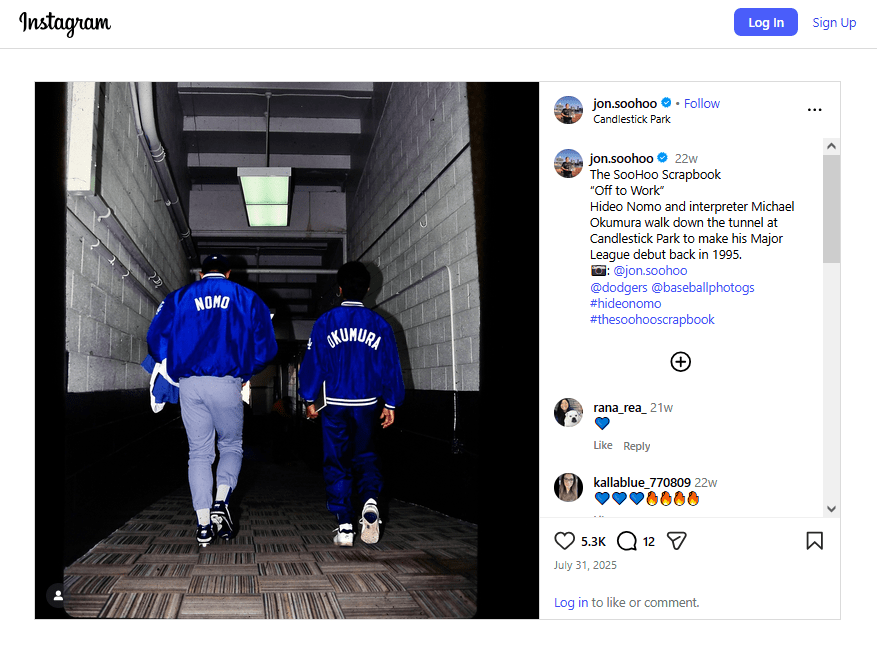

The Dodgers’ first blast of international flavor was, a year before Park, signing Japan sensation Hideo Nomo, the NL starting pitcher in the 1995 All-Star Game and the NL Rookie of the Year Award at age 26.

In ’95, Nomo’s agent, Don Nomura, said he had “the leverage to say, ‘We want this’ (perk because) I believed an interpreter was going to play a major role.”

If you can’t communicate, he said, you can’t succeed. But Nomo had a difficult time cutting loose his interpreter, Michael Okumura.

Los Angeles Times columnist Bill Plaske noted as much when he wrote a piece in spring of 1997 questioning whether Nomo would to himself better by learning and speaking English as Park had done to that point starting his fourth year with the team. “He dropped his interpreter after one season and now speaks with ease,” Plaschke wrote of Park.

Scott Akasaki, who also had been Nomo’s interpreter as part of the Dodgers’ Asian Operations department and eventually became their longtime travel agent in 2005, told the New York Times in 2023: “It’s an underappreciated role. … These guys are lifelines. When you come over, you can’t order a cheeseburger or ask for extra towels or say you’re out of shampoo. It’s a lot more than just balls and strikes.”’

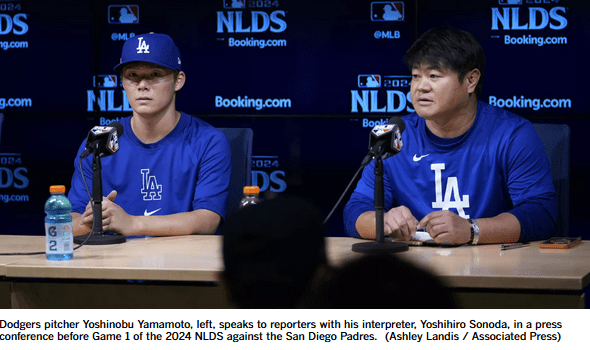

To that point: Two days into the job as the interpreter for the Dodgers’ Yoshinobu Yamamoto, Yoshihiro Sonoda said he wanted to quit. He had no previous experience doing this — he worked in the entertainment industry as a lighting engineer — and he wasn’t up much on baseball terminology. Plus, his wife was living by herself in Texas.

Akasaki had to talk Sonoda out of leaving. “You can learn about baseball if you study it,” Sonoda told Los Angeles Times columnist Dylan Hernandez, recalling what he had been told by Akasaki. “But Yoshinobu chose you for a reason, and that’s something no other person has.”

Before that 2024 season started, the Dodgers discovered the fine line between interpreter and personal assistant can have influencing a star player.

Shohei Ohtani, after six years with the Los Angeles Angels, came over to the Dodgers and brought with him Ippei Mizuhara, who had been an interpreter for English players on the Hokkaido Nippon-Ham Fighters in Japan. Ohtani originally used Hatt Hidaka as his interpreter when he came to the Angels in 2017.

Mizuhara told Sports Illustrated in a 2021 story titled “Beyond Words” that he was not only Ohtani’s catch partner, but he analyzed baseball data for him, and monitored Ohtani’s injury recovery, among a myriad of other duties. Mizuhara told the New York Times in 2023 about the trust factor he has with Ohtani: “It’s such a big part. We are together pretty much every day, longer than I’m with my wife, so it’s going to be tough if you don’t get along on a personal level.”

As it turned out, Ohtani’s trust in Mizhara allowed the interpreter to be caught up in a gambling scandal in 2024, just as the Dodgers’ season was starting with games in South Korea — where Park was throwing out the ceremonial first pitch. Mizhara ended up serving five years in prison for stealing some $17 million from Ohtani to pay off debts incurred with an Orange County bookmaker.

Mizuhara said he made between $300,000 and $500,000 working with Ohtani, which is on the higher end for interpreters working with Asian players.

Will Ireton, aka “Will The Thrill,” who had been with the Dodgers the previous eight seasons and was in the Performance Operations department at the time, became Ohtani’s his new translator, having acted as an interpreter for pitcher Kenta Maeda from 2016 to ‘19. Ireton had also been interpreting for Dodgers pitcher Yoshinobu Yamamoto. Ireton was born in Tokyo to a Japanese American father and Spanish Filipina mother. He came to the United States at age 15 and later was an infielder at Occidental College and, while playing at Menlo College, was its valedictorian for the class of 2012.

Ireton was the one who translated Ohtani’s words: “I never bet on baseball or any other sports, or have never asked somebody to do on my behalf and I have never went through a bookmaker to bet on sports.”

Some days, it seems like the interpreter’s pay scale has to cover much more than one may bargain for.

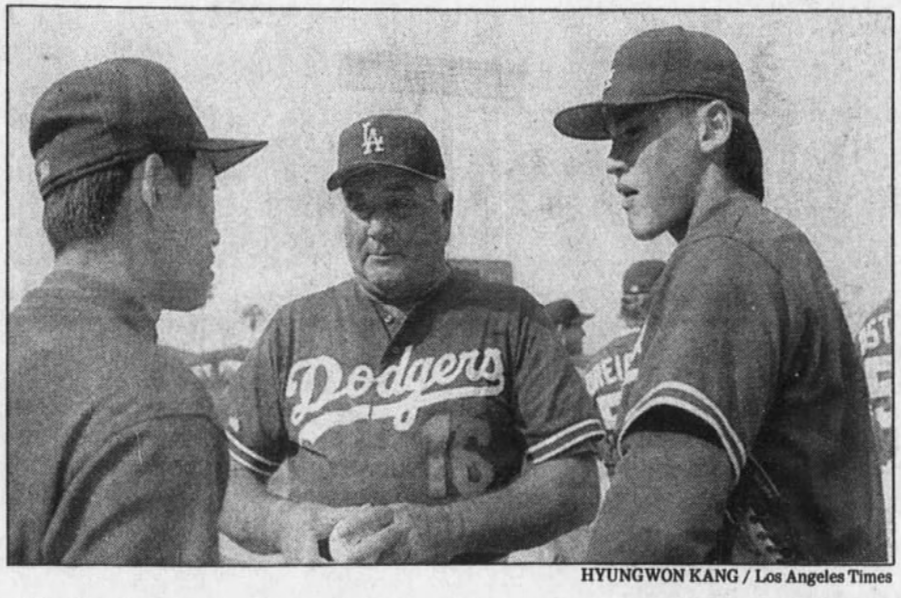

To think of how far MLB interpreters have come some 30 years after Yi first did the speaking for Park, consider how things had to be figured out in Park’s first intrasquad game of the Dodgers’ 1994 spring training. Park walked leadoff batter Delino DeShields. Catcher Tom Prince approached the mound to go over signs. Halfway there, Prince remembered to wave Yi to the mound as well.

“I was a little nervous because I thought Brett Butler was leading off, but it was Delino DeShields,” Park said through Yi.

Park made his first appearance in an exhibition game in early March, giving up one hit and one walk in three innings, and drew hordes of news reporters to the Dodgers locker room.

“Ladies and gentleman ….” Park began, in English, before turning to Yi with a grin.

Yi also had to help the Dodgers, and National League umpires, decipher some quirks in Park’s pitching delivery, which included a bit of a hesitation. Some opposing players stepped out of the batter’s box asking for time out during Park’s delivery. Park had been called for balks four times in his first three springs tarts.

National League umpire Bruce Froemming held a meeting before a spring training game with Park, Yi, and Dodgers pitching coach Ron Perranowski.

“In the U.S., the umpires seem to be preoccupied with talks,” Park said through Yi.

Park and the Dodgers got word in late March from the commissioner’s office that his hesitation-kick delivery has been ruled illegal.

“It really doesn’t matter to me,” Park said through Yi. “It’s just one of the many things that I do.”

Yi might have enjoyed the fact he could be treated to staying in nice hotels, fly on the team plane and have other perks, but the 24/7 job had no vacations or sick days. Yi also had to figure out how to spend his time trying to navigate all the interview requests. At one point early in the season, a media crush of reporters who spoke English, Spanish and Korean showed up to talk to Park. Yi was elsewhere being interviewed himself. Dodgers manager Tommy Lasorda could stand in next to Park and helped translate questions from the Spanish media.

Park’s Dodgers teammates also needed Yi’s help for simple communication.

“We have become pretty good friends over the last six weeks,” said Dodgers reliever Darren Dreifort. “The language barrier is a little bit of a problem, but Don Yi does a good job.”

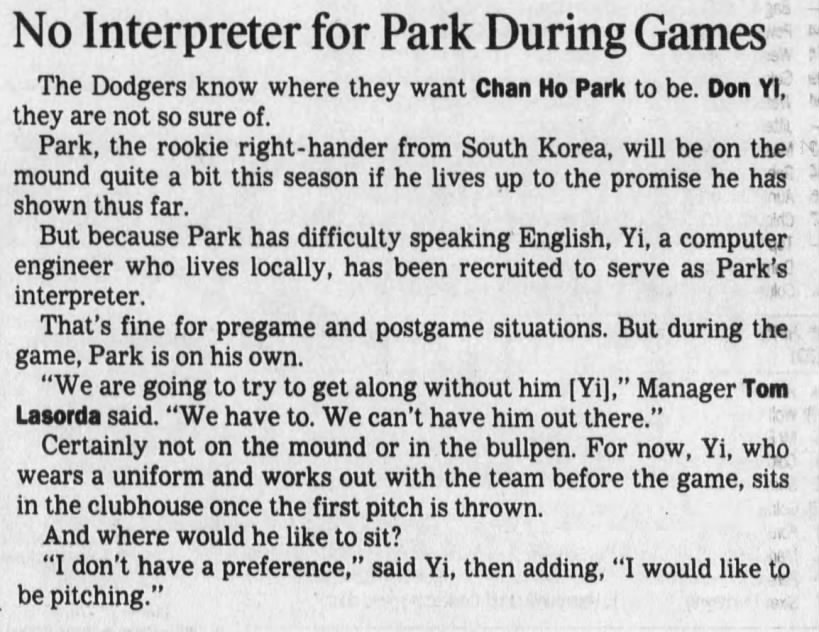

The Dodgers and bullpen coach Mark Cresse had figured out a way to use large cue cards to communicate with pre-written Korean phrases. It was then determined by manager Tom Lasorda that Yi could be with Park in the bullpen before the game, but when the first pitch was thrown, Yi seemed to be banished to the clubhouse.

“We are going to try to get along without him (Yi),” Lasorda said. “We have to. We can’t have him out there.”

Yi was asked where he would like to sit and watch games.

“I don’t have a preference,” said Yi, then adding, “I would like to be pitching.”

When the Dodgers opened the season at home with six games in early April, members of a Korean television station based in Seoul and about 15 local Korean journalists were on hand to follow around Park. His debut came in the Dodgers’ fourth game — April 8, 1994. Its historic nature was overshadowed by a 6-0 no-hitter thrown against the Dodgers by the Atlanta Braves’ Kent Mercker at Dodger Stadium.

Park pitched two innings in relief, giving up two runs, striking out two and walking two before 36,546. Lasorda handed him a baseball after that outing as a keepsake. Park didn’t understand the magnitude. So he went into the clubhouse, and asked Yi.

‘That’s your first strikeout ball,” Yi told him. At the time, Park said he didn’t care. He felt embarrassed for allowing two runs. He quickly learned, however, to appreciate what all his milestones meant.

“It’s all meaningful for me since then,” Park said. “So every new ball or home run ball, base hit ball, all were firsts, right? So I started collecting the balls. That’s all in a museum in my hometown in Korea.”

He made his next relief appearance at St. Louis against the Cardinals on April 14 at Busch Stadium, going three innings and giving up three runs, striking out four and walking three. His ERA swelled to 11.25.

“The fact that I don’t know the hitters is difficult,” Park said after that game through Yi. “But I’m learning the batters now and getting better because of it.”

While on that trip to St. Louis, Park had lunch with Dreifort and Orel Hershiser when a group of Koreans approached him for his autograph.

“I am being recognized by many people now, not just Koreans,” Park said through Yi. “It happens in Glendale (where Park lives), in L.A., and here.”

Yi added to the story that Park, Hershiser and other Dodgers also went to see the movie “Major League II” during a rain postponement.

“Chan Ho kept comparing the players in the movie to his teammates,” said Yi. “You know the guy with the leather jacket who gets traded to the White Sox? Well, when he walks in the clubhouse with his sunglasses on, Chan Ho says, ‘There’s Roger McDowell.’”

Park said through Yi that he understood English better and “the other players are patient and understand. (On the mound) I understand when Mike Piazza talks to me. Baseball is a professional language and I don’t have difficulty there, Plus Piazza goes out of his way for me.”

By 1997, Piazza, now an All-Star catcher, was front and center trying to figure out the best ways to communicate not just with Park and Nomo, but also a starting rotation that included by Spanish-first speakers Ismael Valdez, Ramon Martinez and Pedro Astacio. There was also up-and-coming Mexican player Dennys Reyes. It was said Piazza, and pitching coach Dave Wallace were working overtime communication to the International House of Pitchers.

Perranoski said Park stopped by his locker before a game and communicated for the first time without Yi, using hand signals and what little English he knew by then.

“Chan Ho has been very defensive pitching-wise, and I have told him to throw his fastball more, but he’s been tentative,” Perranoski said. “I had taken him back to the clubhouse between innings (during his previous outing) and told him, using his interpreter, to throw more fastballs. And when he went out there the last inning, he got more aggressive.

“But today he stopped by to tell me that mentally he had been putting major league players up high, and his pitching, low. He used broken English, and pointed up high and then low, and then said that after his last inning, he realized that he is even with the batters. I pointed to my head, and he nodded. What he was telling me is that he has his confidence back.”

However, in late April, the Dodgers sent Park to Double-A San Antonio to work on his mechanics as he wasn’t getting enough innings on the big-league level. Yi went with him, moving into the same San Antonio hotel and going on the lookout for local Korean restaurants.

In his 2014 autobiography, Park wrote: “I heard that if I do well in a few games (in the minor leagues), I can go back to the Majors. I thought, oh really? Then I can go back pretty soon. But that was not so. I thought I was doing pretty well, but the coach (Burt Hooton) said so-so. Not good. About a month passed, and then it got difficult. I was lonely and frustrated. Even the food made it hard for me.

“One day, after about a month, the game did not go well. I gave up eight runs in four innings, and I was switched out. I was so sad and so embarrassed. At the time I was always with my translator. I didn’t say a word to the translator and left the stadium. I started walking. I didn’t want to get in the car and go back to my apartment. Thinking back now, it was quite foolish. But at the time, I was not of a mindset to be thinking. I just wanted to be alone. From the stadium to the apartment, I had to go on the freeways. It took about 15 minutes by car, but it took about 3 hours by walking. I walked on the freeway.

“Later, when people found out that I disappeared from the stadium, the organization panicked. Illegal immigrants or the homeless could pick a fight. There could be gun fights. Cars drive by at high speed. When I came home after three hours, my translator said it was crazy at the stadium and warned me to never do that again.

“But I decided to run that route every day. So from now on, I am going to run from the apartment to the stadium. I remembered how I used to train so hard in Korea, and I wanted to do that again here. But in the morning when I got out of the apartment, thinking that I’ll run, I hesitated. Should I run? Should I walk? Should I skip today? Should I do it tomorrow? My mind went everywhere, but I held myself tight. Let’s do it. Let’s run.”

By the end of the ’94 season, Park’s agent (and uncle) Steve Kim said “there will be no more interpreters next year.” Park was spending four hours a day studying English at Santa Monica College. “Tommy (Lasorda) and Peter (O’Malley) want to converse directly with me,” said Kim.

Park had a 5-7 record and a 3.55 earned-run average in 20 starts with San Antonio. He struck out 100 and walked 57 in 101 1/3 innings.

He would spend the first eight season of his 17-year MLB career with the Dodgers from ’94 to 2001, when he made his only All-Star appearance. He came back for a season in 2008 and posted 84 of his 124 wins as a Dodger over 275 games, 476 overall having learned to speak English and play in Texas, San Diego, Philadelphia, Pittsburgh and in New York with both the Mets and Yankees.

“There were a lot of things Chan Ho didn’t understand,” said Hooton, Park’s pitching coach with the San Antonio Missions. “When he came down, he thought that he was going right back. At first, he didn’t understand the long process. Aside from talent, he has much further to go than other kids, with coming over to this country for the first time, not knowing the language, experiencing a different culture, a different diet.”

As it turned out, Yi spent just a half season with Park, saying he had to return to L.A. to run his computer business. An interpreter named Billy Che came into help Park, who by then had picked up words and phrases such as “Hey dude” and was playing Elvis Presley music in his Walkman.

“Verbally, people prepared us for the difference between the big leagues and the minors, but boy, were they ever right,” Yi eventually told the Los Angeles Times. “I remember our first road trip, we were sitting in this little bus for about six hours. But we didn’t actually complain to each other too much.”

Yi’s status these days? It’s something of a mystery. Dodgers owner Peter O’Malley relayed to us that he doesn’t recall how he tagged Yi in the first place to help Park. Dodgers team historian Mark Langill can’t find any file photos of Yi either.

Maybe it’s just a reflection of how the job is evolving.

When the Dodgers gathered for the start of 2026 spring training in Glendale, Ariz., Ohtani was asked by Bill Plunkett of the Orange County Register if he would continue to need the services of interpreter Ireton. It was pointed out that when Ohtani was honored with his 2025 National League Most Valuable Player Award, and he gave his acceptance speech in English. The two-minute-long address prompted Plunkett to wonder if Ireton “would soon be out of a job.”

“I still need him because there might be some bullies out there that might give me some weird questions that I’m sure he can handle,” Ohtani said

Plunkett added that Ohtani then gave him “the first side-eye of the spring.”

Who else wore No. 94 in SoCal sports history? Make a case for:

Kenechi Udeze, USC football defensive lineman (2000 to 2003):

Best known: “BKU, for “Big Kenechi Udeze,” a prep All-American lineman at L.A.’s Verbum Dei High who was also a shot putter on the track team, got in three years at USC punctuated by All-American status and the sport’s National Defensive Player of the Year on the Trojans’ national title team in ’03. That season he led the nation in sacks (16.5), was fourth in tackles for a loss (26), ninth in forced fumbles (5) and the only player in the nation in the Top 9 in each of those categories. For his career, he recorded 135 tackles, 51 tackles for loss, 28 sacks, an NCAA record-tying 14 forced fumbles and three fumble recoveries. When he enrolled at USC, he weighing 375 pounds. When he left, he was at 275.

Not well known: A 20th overall selection by Minnesota in the 2004 NFL Draft, Udeze’s fourth year in the league was marked by constant pain. After the 2007 season, he was diagnosed with leukemia. A bone marrow transplant in ’08 helped him battle it enough to where he tried to return to the NFL in 2009, but he developed peripheral neuropathy in his feet from chemotherapy, causing painful numbness. As he retired before the season started, Udeze returned to USC to not just earn his bachelor’s degree in sociology in 2010, but after he turned to coaching, he was back on campus as an assistant strength and conditioning coach in 2015. He was named defensive line coach in 2016.

Paul Bergmann, UCLA football tight end (1979 to 1983):

Well known: John Elway’s favorite target during their days at Granada Hills High — in a 1979 All Star Game at the Rose Bowl, Elway threw him a 50-yard pass that he caught one-handed — Bergmann came to UCLA and effectively sat three seasons before he played in ’82 and ’83, totaling 85 catches for 1,076 yards in 24 straight games, all-time records for tight ends. He had a game-best six receptions in UCLA’s win over Michigan in the 1983 Rose Bowl and had four receptions and a touchdown in UCLA’s upset over No. 4 Illinois in the 1984 Rose Bowl.

Not well known: Bergmann, a second-team All-American at UCLA, spent two years in the USFL and three seasons with the NFL’s Kansas City Chiefs. He served as the senior pastor at the Ojai Valley Community Church in 1998 to 2021, hosting a Super Bowl watch party for his congregation in 1999 to enjoy Elway’s final game in the NFL.

Mateen Bhaghani, UCLA football kicker (2024 to 2025):

Best known: A third-generation Pakistani nicknamed “Money Bhags,” Bhaghani hit a 32-yard field goal with 56 seconds left to give UCLA a 16-13 win over Hawaii in his first game as a Bruin. He had a Big Ten-best 20 field goals (and scored 80 points) during his first season in Westwood, having transferring from Cal, where he wore No. 49 and then reversed the numbers. In 2025, Bhaghani was 16-for-20 (80 percent) on field goals and 22-for-22 on extra points, giving him 71 of 71 for his career (which includes a freshman season at Cal). After making 36 of 44 field goal attempts at UCLA, Bhaghani entered the transfer portal after the 2025 season.

Not well known: “I’m very prideful,” Bhaghani said of his heritage as one of the few South Asian football players ever in college or professional ranks. “It’s very important that there’s people of all races in all sports, because I just want to show younger kids and people of my culture that anything is possible.”

Have you heard this story:

Terry Crews, Los Angeles Rams middle linebacker (1991):

Best known: First as the character “T-Money” for two seasons of the reality TV show “Battle Dome,” and then a choice by Adam Sandler to have him suit up in the remake of “The Longest Yard,” Crews spent eight seasons as Terry Jeffords on “Brooklyn Nine-Nine,” allowing him to flex his pecs on command.

Not well known: The 6-foot-2, 245-pounder out of Western Michigan became the Rams’ 281st overall pick (11th round) in 1991 and got into six games for a team that went 3-13 under John Robinson, his last with the franchise. After a season in San Diego (1993) and Washington (1995), Crews was done with the NFL pursuit.

Javier Herrera, Los Angeles Dodgers bat boy/ball boy (2006 to present):

Best known: It wasn’t until Herrera was 38 years old and part of the Dodgers’ equipment crew that maybe he finally got his close up. During a Dodgers’ 4-0 win at the Chicago White Sox on June 26, 2024 at Dodger Stadium, Herrera was standing next to star Shohei Ohitani in the dugout when Kiké Hernández slices a line drive toward the visitors dugout. Herrera caught the ball before it could hit Ohtani. It went viral as it was caught when a Japanese TV camera was poised on Ohtani. “I don’t know what happened,” Herrera told the New York Times. “I was just doing my job. … I saw the pitch all the way through, it hit the bat, and the ball pretty much found me. But I was able to grab it.” “My hero,” Ohtani posted on his Instagram story.

Not well known: Herrera first drew attention in a Dodgers uniform in 2016 when he took a tumble attempting to retrieve a foul fly ball as he was stationed down the third-base line, catching the attention of Vin Scully on the broadcast. “I lay there thinking, ‘Oh my gosh, what did I just do?’” he told The Times’ Bill Plaschke. “‘I just embarrassed myself on national TV!’ … I thought I might get heckled. I did not think I would get cheered.”

Anyone else worth nominating?

1 thought on “No. 94: Don Yi”