This is the latest post for an ongoing media project — SoCal Sports History 101: The Prime Numbers from 00 to 99 that Uniformly, Uniquely and Unapologetically Reveal The Narrative of Our Region’s Athletic Heritage. Pick a number and highlight an athlete — person, place or thing — most obviously connected to it by fame and fortune, someone who isn’t so obvious, and then take a deeper dive into the most interesting story tied to it. It’s a combination of star power, achievement, longevity, notoriety, and, above all, what makes that athlete so Southern California. Quirkiness and notoriety factor in. And it should open itself to more discussion and debate — which is what sports is best at doing.

The most obvious choices for No. 90:

= Larry Brooks, Los Angeles Rams

= Mike Wise, Los Angeles Raiders

The most interesting story for No. 90:

Andrei Voinea, California School of the Deaf Riverside football center, offensive lineman, tight end (2021 to 2022)

Southern California map pinpoints:

Riverside, Burbank

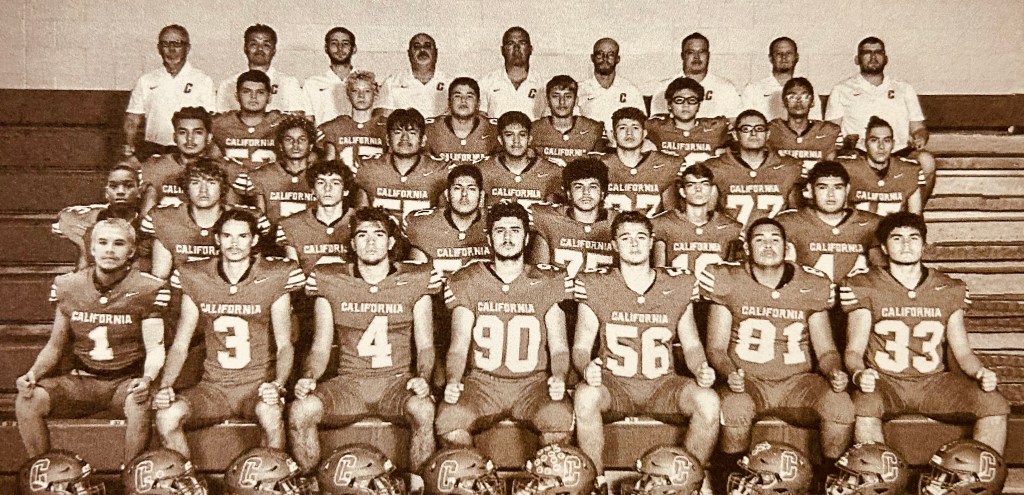

In the 2022 team photo of the California School of the Deaf Riverside high school football squad, No. 90 Andrei Voinea is front and center.

The starting center on the offensive line by season’s end, Voinea may not have been the most athletic or talented of a team that would go on to win a championship, but he was the biggest and perhaps the quickest learner, with a computer science mind and newfound appreciation for how he could converse with classmates.

The position of center who starts the play is vital, not only in an eight-man football alignment where the line works harder on protection after the snap. But, as the name of the school indicates, unique communicate is needed before and after the snap. It’s a skill set that starts in the school’s classrooms, social networking, and transfers to the football team’s collective success.

That photo also shows Trevin Adams, No. 4, the team’s quarterback/linebacker captain, next to Voinea. Adams is the son of the head coach, Keith Adams, up there in the back row, five in from the left. Trevin’s younger brother, freshman Kaden, was his backup at quarterback.

Jory Valencia, No. 3, is next to Adams, the team’s 6-foot-3 senior captain at wide receiver and cornerback. His grandfather Seymour Bernstein came to the school in 1958 and coached football. His parents, Jeremias and Scarlett, both attended CSDR and excelled in sports, as did his older brother Noah and his uncles Joshua Valencia, Jonathan Valencia, Steve-Valencia-Biskupiak and Ethan Bernstein.

Next to Valencia is Felix Gonzales, No. 1, the team’s most outstanding player and another senior captain. By the end of the season, Gonzales was recovering from a leg injury and couldn’t make the team picture. The school deftly edited him in digitally for this team shot.

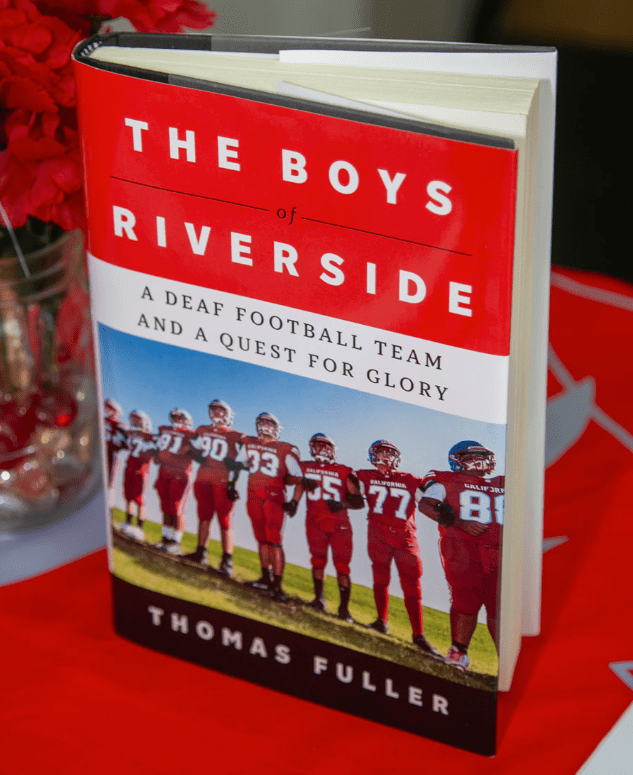

All of them and more make up the central casting of the 2024 book, “The Boys of Riveside: A Deaf Football Team And a Quest for Glory.” Note on the cover: Voinea, fourth in from the left, linking arms with teammates.

New York Times writer Thomas Fuller introduces Voinea and his teammates who, coming out of a COVID confusion that shutdown all the school’s sports, happened to be at the right place at the right time to make California School of the Deaf Riverside a rather improbable California Intercollegiate Federation (CIF) Southern Section champion.

“It was so quintessentially American,” Fuller, struck by the students’ perseverance, eventually described it to People Magazine. “A team that had endured seven decades of losing seasons was now beating the pants off of all their opponents.”

Listen as these Cubs roar.

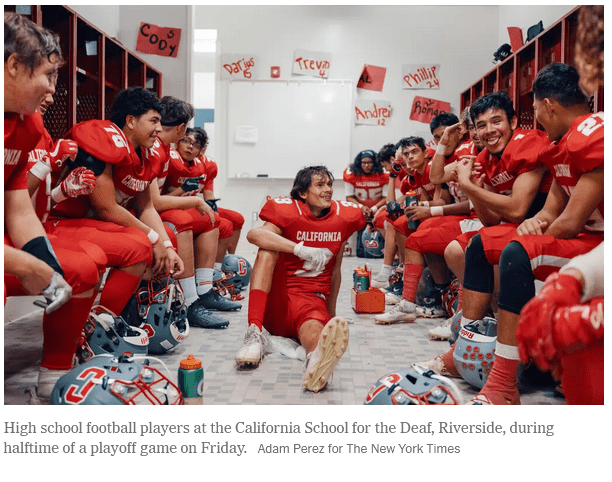

On the wall behind them are posters of players’ names and numbers. One of them is “Andrei 12.”

Voinea wore No. 12 as a junior (as well as when the team was on the road and needed a white jersey) because “Tom Brady was my favorite player in the NFL,” he said.

He wore No. 90 more in his senior year, admitting “it sounds bigger and more fitting for my size, considering most of the big guys in the NFL chose higher jersey numbers.”

Below: A photo of Voinea wearing No. 12 during a game at Avalon High on Catalina Island.

A year earlier, in 2021, the Cubs made noise as the first in the school’s 68-year history to advance to a section championship game. Scores of local and national media outlets came along for the ride and a storyline that was too good to pass on — a team of deaf players, at a school with more than 50 years of losing seasons, rose up out of COVID and did something remarkable.

Even though CSDR lost that title game, 74-22, to Faith Baptist of Canoga Park, the 2022 team went all the way on a 12-0 run, avenging the defeat with a convincing 80-26 win over the same Faith Baptist program.

Continue reading “No. 90: Andrei Voinea”