This is the latest post for an ongoing media project — SoCal Sports History 101: The Prime Numbers from 00 to 99 that Uniformly, Uniquely and Unapologetically Reveal The Narrative of Our Region’s Athletic Heritage. Pick a number and highlight an athlete — person, place or thing — most obviously connected to it by fame and fortune, someone who isn’t so obvious, and then take a deeper dive into the most interesting story tied to it. It’s a combination of star power, achievement, longevity, notoriety, and, above all, what makes that athlete so Southern California. Quirkiness factors in. And it should open itself to more discussion and debate — which is what sports is best at doing.

The most obvious choices for No. 80:

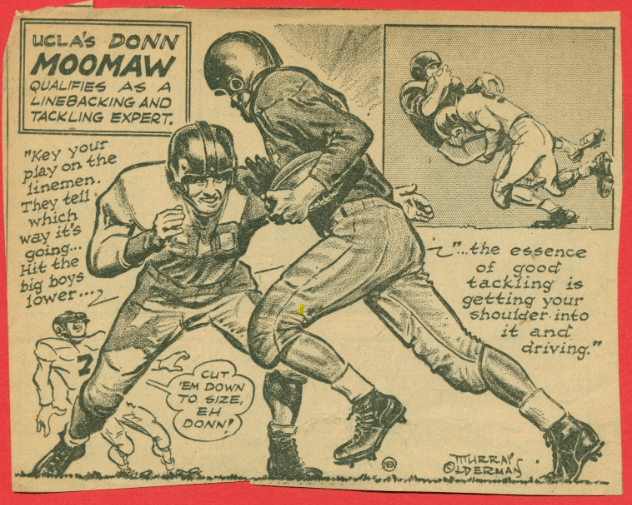

= Donn Moomaw, UCLA football

= Henry Ellard, Los Angeles Rams

= Johnnie Morton, USC football

The not-so obvious choices for No. 80:

= Bob Klein, USC football, Los Angeles Rams

= Duane Bickett, USC football

The most interesting story for No. 80:

Donn Moomaw, UCLA football center and linebacker (1950 to 1952)

Southern California map pinpoints:

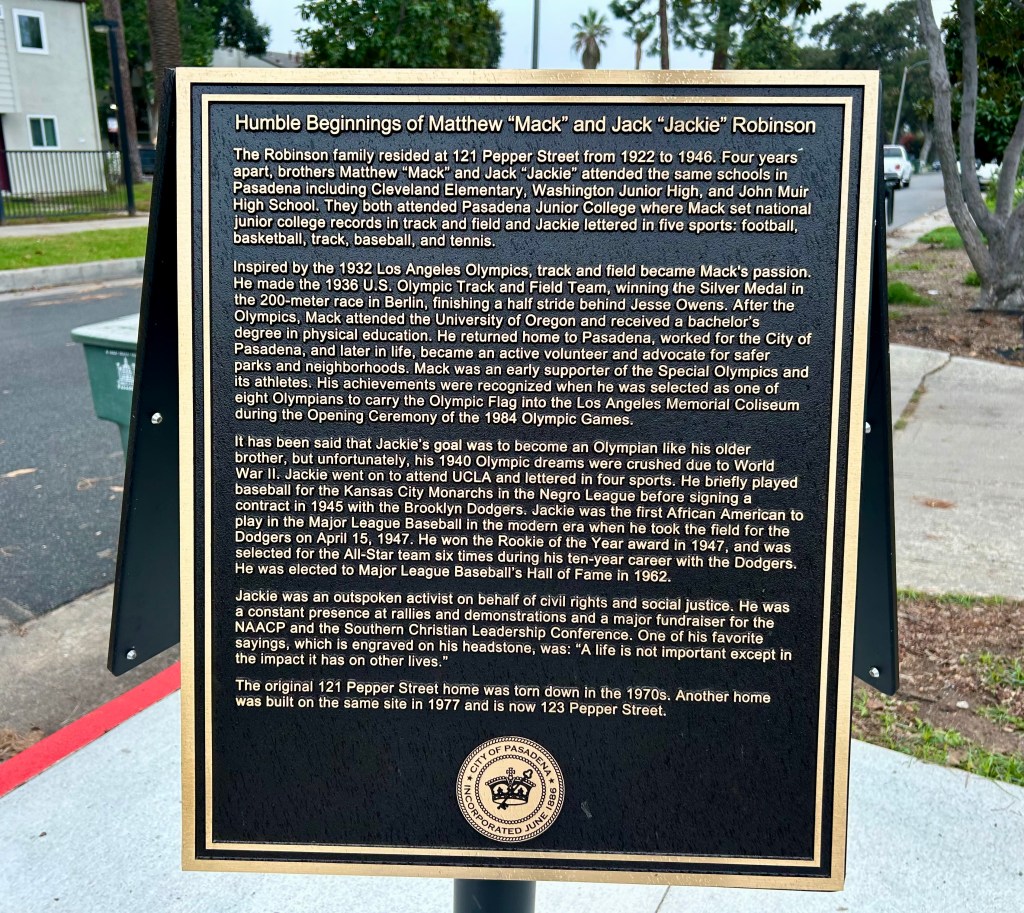

Santa Ana, Westwood, Los Angeles (Coliseum), Hollywood, Bel Air, Pasadena

With their first pick in the 1953 NFL Draft — the ninth-overall choice — the Los Angeles Rams selected center/linebacker Donn Moomaw, the first two-time All-American in UCLA program history and a local hero out of Santa Ana High.

Moomaw prayed on it.

Then he politely declined.

The NFL played Sunday games, which was Moomaw’s day for the Lord. It did not need any potential Hail Mary pass plays intercepting his focus.

As an end around, Moomaw could deflect to Canada, play for the Toronto Argonauts and the Ottawa Rough Riders in the CFL, and do more mid-week and Saturday engagements.

But soon enough, his rough ride of long-term pro football fame came with a change in heart. Moomaw became one of the most well-known preachers in the country. The fresh Presbyterian minister of Bel Air became a personal confidant of Ronald Reagan and his family, starting with his time as the California governor, and going all the way to the White House.

But then, the headlines that Moomaw made later in life were a cause to pause and pray some more.

The story

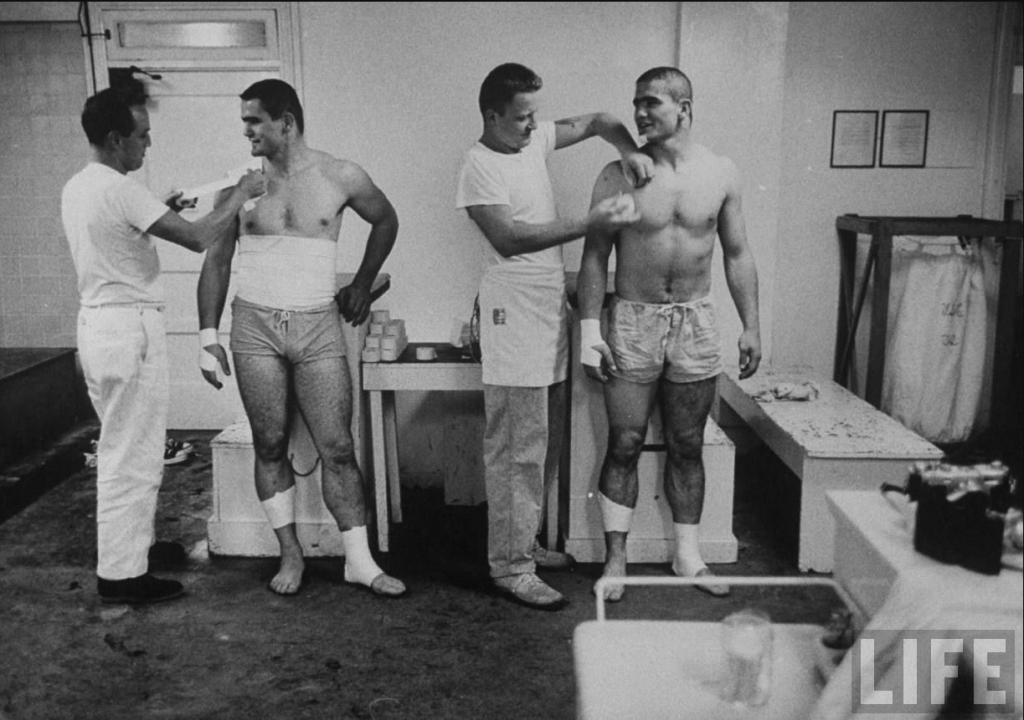

Don Moomaw’s time at UCLA was a glorious one. They weren’t booing him. When the 6-foot-4, 220-pound linebacker made a tackle, the UCLA cheerleaders would lead the crowd in “MooooooMAW!” He was known as “the Mighty Moo.”

He came just as advertised out of Santa Ana High.

Continue reading “No. 80: Donn Moomaw”