This is the latest post for an ongoing media project — SoCal Sports History 101: The Prime Numbers from 00 to 99 that Uniformly, Uniquely and Unapologetically Reveal The Narrative of Our Region’s Athletic Heritage. Pick a number and highlight an athlete — person, place or thing — most obviously connected to it by fame and fortune, someone who isn’t so obvious, and then take a deeper dive into the most interesting story tied to it. It’s a combination of star power, achievement, longevity, notoriety, and, above all, what makes that athlete so Southern California. Quirkiness factors in. And it should open itself to more discussion and debate — which is what sports is best at doing.

The most obvious choices for No. 95:

= Jamir Miller, UCLA football

The not-so-obvious choices for No. 95:

= Roger McQueen, Anaheim Ducks

The most interesting story for No. 95:

Jamir Miller, UCLA football outside linebacker (1991 to 1993)

Southern California map pinpoints:

Westwood, Pasadena

Jamir Miller’s jam at UCLA, aside from chasing down quarterbacks, seemed to be a persistent pursuit of parties. That didn’t stop until he was well into a career in pro football.

An All-American linebacker who, in just three seasons with the Bruins would lead the team in sacks each year, rack up a then-school record 23 ½ total, added 35 tackles for a loss, and was a Butkus Award finalist by the time he was done with college football, Miller said he once assessed that by his sophomore year in Westwood, “I embarked on the wild phase of my life that lasted through my second year in the NFL,” according to the Cleveland Plain Dealer in August of 2000.

That didn’t include a senior year of college in that time frame.

The 6-foot-5, 252-pounder was arrested twice at UCLA — once for possessing a loaded firearm and once for accepting stolen stereo and computer equipment. He pleaded no contest to both charges, was placed on three years probation and required to perform 100 hours of community service.

Miller also was suspended for the 1993 season opener by head coach Terry Donahue, a person who Miller credits for being most responsible for recruiting him to come to UCLA and tell his mother that her son would be taken care of. UCLA not only lost that first game of the season, 27-25, to Cal, but also the second game, 14-13, at the Rose Bowl against Nebraska, to started 0-2. That would be the last season for Miller at the school.

Miller’s missteps followed a bit of a pattern he developed as a kid growing up with a single mom in the Oakland area, trying to figure out his identity.

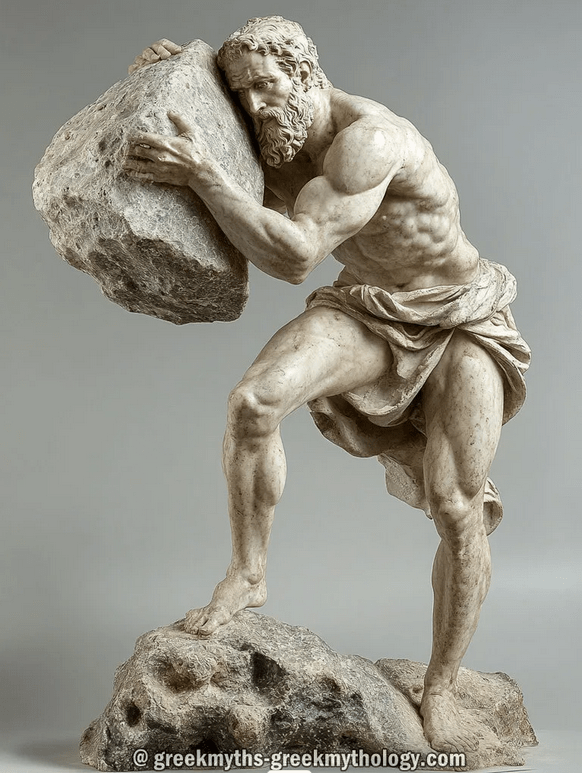

Jamir Malik Miller — his first and middle names mean royal warrior in Swahili — said he didn’t feel much like a warrior growing up.

“When I was younger I didn’t really like my name because it was different and a lot of people couldn’t pronounce it,” Miller told the Los Angeles Times in 1992. “They mess it up and say ‘Jamal’ and I’d go, ‘No, it’s Jamir .’

“I was in the fourth or fifth grade and I’d come home and say, ‘Mom I hate my name because no one can pronounce it.’ She told me not to worry, that I’d understand it when I grew older.

“I wanted to change my name to something like John. I wish my mother had named me something normal. But I decided to stick with it because that’s my identity. And now I’m glad she didn’t name me something normal.”

John Miller was the name of Jamir’s father. A hardened intravenous drug addict, John’s actions forced Jamir’s mother, Rhonda Hardy, to take him as a 3-month old out of their home in Philadelphia and move in with her mother and sisters in the Bay Area.

Continue reading “No. 95: Jamir Miller”