The book: “Tinker to Evers to Chance: The Chicago Cubs and the Dawn of Modern America”

The book: “Tinker to Evers to Chance: The Chicago Cubs and the Dawn of Modern America”

The author: David Rapp

How to find it: University of Chicago Press, 336 pages, $27.50, released April 2

The links: At Amazon.com, at the publisher’s website.

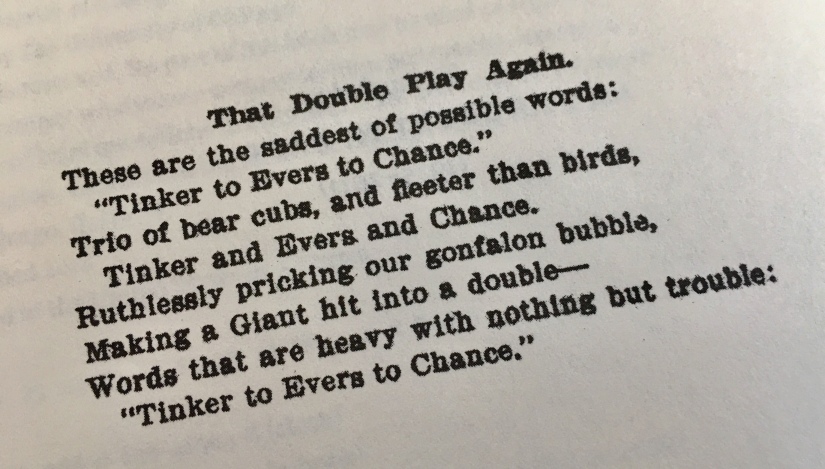

A review in 90-feet or less: Using the ironic eight-line poem about an infield that anchored a team to the World Series 100 years ago as a starting point, Rapp goes around the horn to make a case that they were not only justified by their stanza super powers, but makes a case they carried the game during that era with an extensive background check that’s a surprisingly thorough in what could otherwise be a rehash of previous works on the subject.

A review in 90-feet or less: Using the ironic eight-line poem about an infield that anchored a team to the World Series 100 years ago as a starting point, Rapp goes around the horn to make a case that they were not only justified by their stanza super powers, but makes a case they carried the game during that era with an extensive background check that’s a surprisingly thorough in what could otherwise be a rehash of previous works on the subject.

The preface thankfully explains how “Baseball’s Sad Lexicon” came into being in 1910 – a printing error, where the New York Evening Mail came up short on F.P. Adams’ column and had to dream up six more lines to fill it out.

If only journalism history was that glamorous.

And thanks for teaching us the word “gonfalon.”

Unlike “Casey at the Bat,” this “terse ditty used a different kind of irony to celebrate three living ballplayers and their sport’s newfound status as the ‘national pastime’.” So there.

Now consider that from 1906 to 1910, manager Frank Chance’s team won 530 games – a major-league record to this day – plus two World Series titles and four NL pennants. The threesome became a threesome in 1903 and didn’t split up until eight seasons later when Chance retired. Without that, there’s no foundation and context for what the Dodgers’ infield of Garvey, Lopes, Russell and Cey did in the 1970s and early ‘80s — a feat that didn’t even warrent a clever haiku about them.

The timing of the Tinker-Evers-Chance chance gathering — and let’s go ahead and answer now the Abbott and Costello-like trivia question about who was the third baseman, a pretty good player himself in Harry Steinfeldt — happened at a time when baseball needed a post-King Kelly push into credibility. The game was starting to get shoved into the deplorable category of prize fighting and horse racing as corrupt and unsavory.

It needed family values.

Of the three, Chance’s background resonates here most because of the unique upbringing in Fresno, with a well-to-do father who took advantage of recent California statehood and built his own success story, with connections to “Lucky” Baldwin of Santa Anita Park horse racing fame.

Frank Chance was much more interesting in boxing, but baseball eventually was the payoff when he moved to Chicago – and then insisted on playing catcher.

The Colts – later named the Cubs – also took frequent spring training trips to California to play some of the California League teams, no doubt a connection that was continued later with team owner Phil Wrigley having the Los Angeles Angels as his farm team and bringing the Cubs to train at Catalina Island decades later.

The book reveals that Evers and Tinker really didn’t get along, and often fought. But they created a truce for their constant bickering for the good of the team that Chance tried to keep pulled together.

As for their place in history, this Cubs’ infield was part of several touchstone moments. They were playing in a game when President Taft stood in the seventh inning to stretch and appeared to start a tradition. They were the ones who noticed “Merkle’s Boner” during a Cubs-Giants pennant race and tried to immediately rectify it. They were also involved in a game in Brooklyn where Chance ended up with a week-long suspension for throwing a soda bottle back into the rowdy crowd after he was nearly hit with it.

As it turned out, all three infielders had a chance at managing the Cubs in that era. Chance, the real Hall of Famer in the bunch whose retirement in spring of 1912 led to him moving to Glendora to run an orange grove and construction business as well as become involved in the L.A. Angels as an owner and manager, was succeeded on an interim basis by Tinker, who then got into a another fight with Evers, who was then asked to take over as manager in 1913 and Tinker was traded to the Reds.

Stuff you can’t make up.

A reunion of sorts in name only happened in 1946 when the three were inducted together into the Baseball Hall of Fame, whether or not decades later there’s evidence to try to show it wasn’t truly appropriate.

Or was it?

“Tinker, Evers and Chance were the indisputable leaders of a great team that won a huge number of games,” Rapp concludes. “ ‘The definition of a great ballplayer is a ballplayer who helps his team to win a lot of games,’ baseball historian Bill James has said. ‘If you’re going to say these guys don’t belong in the Hall of Fame … you have to deal somehow with the phenomenal success of their team’.”

How it goes down in the scorebook: An A-plus history lesson. As Rapp concludes in the epilogue: “Until 2016, when the Chicago Cubs won the World Series for the first time in 108 years … few baseball fans knew all that much about Tinker and Evers and Chance, the cornerstone of the franchise’s only prior trophies. Those who have come across their names probably did so through a piece of throwaway verse … We’ve remained true to (the Cubs franchise through decades and even a century) for some strange reason too mysterious to comprehend. Now thanks to Tinker and Evers and Chance, we know why: We can because they cared .. their very lives and triumphs seemed to depend on a childhood game they each felt compelled to play.”

Also:

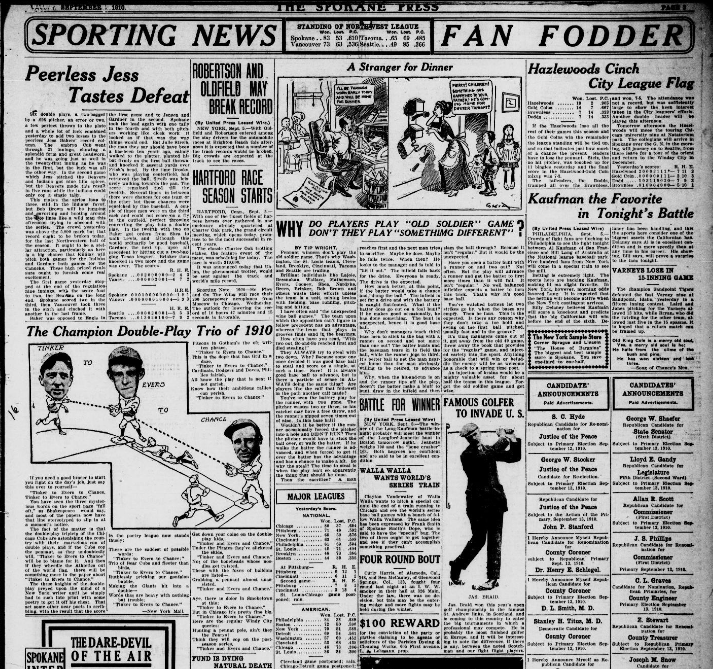

*A copy of the Spokane Press, which ran the syndicated poem in 1910:

2 thoughts on “Day 19 of 30 baseball book reviews for 2018: Poetry in motion — A chance this trio deserves Hall of Fame treatment depends on how you tinker with their impact on history”