This is the latest post for an ongoing media project — SoCal Sports History 101: The Prime Numbers from 00 to 99 that Uniformly, Uniquely and Unapologetically Reveal The Narrative of Our Region’s Athletic Heritage. Pick a number and highlight an athlete — person, place or thing — most obviously connected to it by fame and fortune, someone who isn’t so obvious, and then take a deeper dive into the most interesting story tied to it. It’s a combination of star power, achievement, longevity, notoriety, and, above all, what makes that athlete so Southern California. Quirkiness factors in. And it should open itself to more discussion and debate — which is what sports is best at doing.

The most obvious choices for No. 92:

= Rich Dimler, USC football, Los Angeles Express

The not-so-obvious choices for No. 92:

= Harrison Mevis, Los Angeles Rams

= Rick Tocchet, Los Angeles Kings

= Don Gibson, USC football

The most interesting story for No. 92:

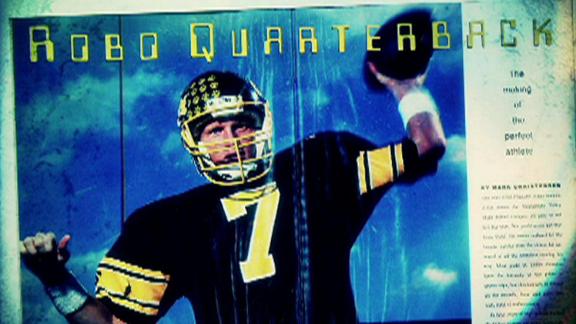

Rich Dimler, USC football nose guard (1975 to 1978), Los Angeles Express defensive tackle (1983 to 1984)

Southern California map pinpoints:

Los Angeles, Glendale, Inglewood, Hawthorne, Torrance, Rancho Palos Verdes

Raise a glass to Rick Dimler. With caution.

The fact he made it through 44 years of roughhousing, and once heralded by USC defensive line coach Marv Goux as “the toughest player I’ve seen in 22 years of coaching” while playing on four straight Trojan bowl victories, is worthy of a toast.

But then again, there was the time when his home town in New Jersey tried to throw a parade in his honor, and it didn’t end well.

Homecomings can be problematic if the honoree celebrates too early and too often.

In March of 1979, Dimler was living off the fame of finishing his four years of football at USC, capped off by a 12-1 season, co-captain of the defensive squad that was highly effective in a Rose Bowl win over Michigan, and giving the Trojans a national championship in the eyes of many voters of such polls.

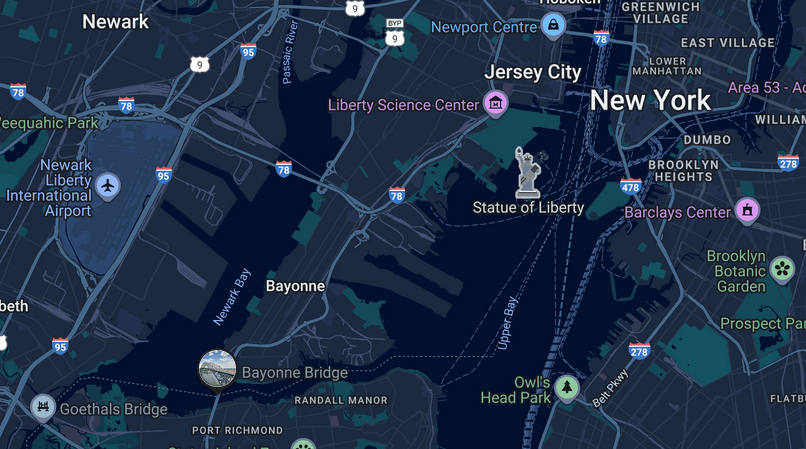

At this point, Dimler was back visiting friends and family in Bayonne, New Jersey. The cityfolk were finalizing plans for what would be Rich Dimler Day — a parade in his honor, a key to the city, the red-carpet treatment. Beers hoisted and thrown back as he could now look forward to what the NFL might bring.

The party was set for April, but, again, Dimler put himself in a situation that had penalty flags flying all over the place.

On March 12, Bayonne police say they saw Dimler in a car racing another car right down Broadway through the city, and started chasing him at 2 a.m. Dimler, according to the authorities, ran three red lights trying to escape. The other car got away. Dimler was hauled in.

At that point, the 6-foot-6, 260-pound Dimler had a dim view on how this might be a teachable moment.

“I’ll have your jobs; I’ll have both your jobs!” Dimler was said to have screamed at the officers, pushing one of them away. He was eventually accused of striking a patrolman in the chest at police headquarters and deemed “unruly” while in the jail cell.

“He flunked his breathalyzer test in flying colors,” said Lt. Vincent Bonner said in newspaper accounts. The .22 result was well above the legal limit of .15.

As soon as Dimler was out on bail facing charges of assault and battery and creating a disturbance, reporters covering the incident discovered he had been arrested just a month earlier in Los Angeles on driving under the influence, but no charges were filed.

Those digging further into his legal history found a disturbing incident in 1973, the year before he left New Jersey to attend USC, when Dimler, then 17, was acquitted of a death by auto charge in juvenile court. He had been charged of hitting and killing a 10-year-old girl as she crossed the street, and he left the scene. All that happened at the time was getting put on probation.

Bayonne City Councilman Donald Ahern — who happened to be Dimler’s high school coach in the mid-’70s — was asked about how all this might tarnish te upcoming day in his honor.

“He’s a good kid with a good heart; I’d be the last guy to leave the ship for that kid,” said Ahern.

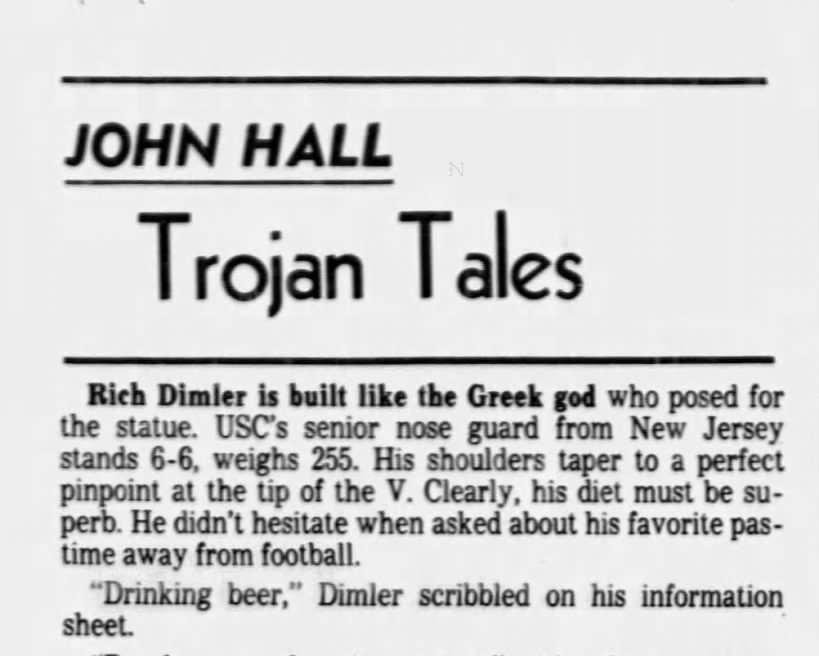

If Dimler needed another character witness, in November of ’78, USC coach John Robinson was telling the Los Angeles Times’ John Hall about how the season had been progressing with Dimler in command of the defense.

“If they ever draw up a blueprint for the ideal leader,” Robinson said, “that’s Dimler.”

Continue reading “No. 92: Rich Dimler”