This is the latest post for an ongoing media project — SoCal Sports History 101: The Prime Numbers from 00 to 99 that Uniformly, Uniquely and Unapologetically Reveal The Narrative of Our Region’s Athletic Heritage. Pick a number and highlight an athlete — person, place or thing — most obviously connected to it by fame and fortune, someone who isn’t so obvious, and then take a deeper dive into the most interesting story tied to it. It’s a combination of star power, achievement, longevity, notoriety, and, above all, what makes that athlete so Southern California. Quirkiness and notoriety factor in. And it should open itself to more discussion and debate — which is what sports is best at doing.

The most obvious choices for No. 49:

= Charlie Hough: Los Angeles Dodgers

= Tom Niedenfuer: Los Angeles Dodgers

= Dennis Smith: USC football

= Charles Phillips: USC football

= Carson Schwesinger: UCLA football

The not-so-obvious choices for No. 49:

= Marvcus Patton: UCLA football

The most interesting story for No. 49:

Marvcus Patton, UCLA football linebacker (1985 to 1989) via Leuzinger High of Lawndale

Southern California map pinpoints:

Inglewood, Lawndale, Westwood

Marvcus Patton had no idea how proud his father might have been, the day UCLA’s football program accepted him as a relatively undersized walk-on linebacker in the fall of 1985.

It was his dad who gave him the name Marvcus, with the extra “v.” Pronounced MARV-cuss, in honor of the Roman emperor and warrior Marcus Aurelius. Marcus comes from the name Mars, the god of war.

“As it turns out, he turned into a warrior on the football field,” his mother, Barbara, told the Los Angeles Times in a 1989 story as her son was about to enter his final collegiate season.

As it also turns out, Barbara was far more influential in Marvcus’ ascent into a football life.

Marvcus’ father, Raymond Hicks, never saw him play. Hicks was a Los Angeles Police undercover detective shot and killed in the line of duty during a drug bust when Marvcus was 9. Hicks had been separated from Barbara for some time at that point, eventually remarried and started another family.

Barbara was a single mom of two children, working as a PBX operation for the federal government’s General Services Administration in L.A. That was her Monday-to-Friday job. On weeknights and on Saturdays, she slugged it out as a linebacker for the Los Angeles Dandelions of the National Women’s Football League.

No flag-grabbing here. Helmets, shoulder pads, extra-thick padding up front. Full on contact. For $25 a day, which sometimes happened, sometimes not.

Like mother, like son. Kind of.

“I thought it was really cool to tell my friends that my mom was a linebacker,” Marvus Patton once shared. “My mom’s love for the game definitely influenced me. I always watched football on television and collected football cards, but seeing my mom play really made me want to be in the NFL.”

The son’s story

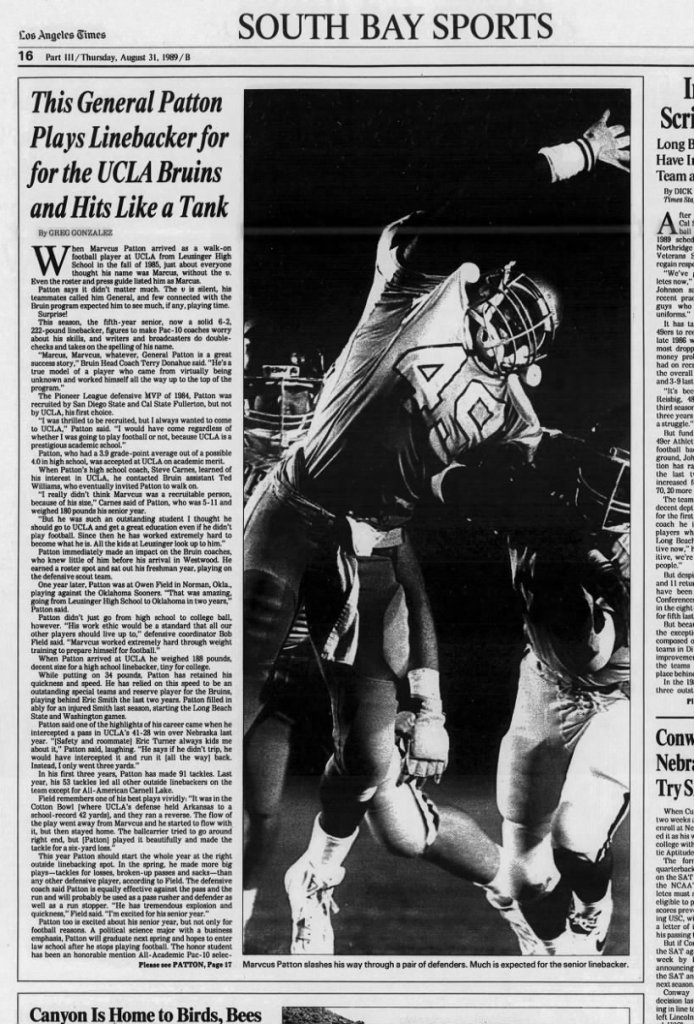

As the Pioneer League defensive MVP at Leuzinger High in Lawndale in 1984, Patton had only one college scholarship offer, from San Diego State. Cal State Fullerton was interested, but it couldn’t commit too much. It didn’t matter. Patton’s first choice was UCLA.

At 5-foot-11 and 133 pounds as a high school junior, he got up to 165 as a senior as he hit the weight room. But college choices were were limited. Academics mattered.

“I would have come regardless of whether I was going to play football or not, because UCLA is a prestigious academic school,” said Patton, who had a 3.9 grade-point average and made it into on scholastic merit. At Leuzinger, he had already completed upper-division classes as a freshman and sophomore and was practically able to graduate before his senior season.

Steve Carnes, Patton’s coach at Leuzinger, connected him with UCLA assistant Ted Williams. Patton was invited to walk on.

“I really didn’t think Marvcus was recruitable,” Carnes said. “But he was such an outstanding student I thought he should go to UCLA and get a great education even if he didn’t play football. Since then he has worked extremely hard to become what he is. All the kids at Leuzinger look up to him.”

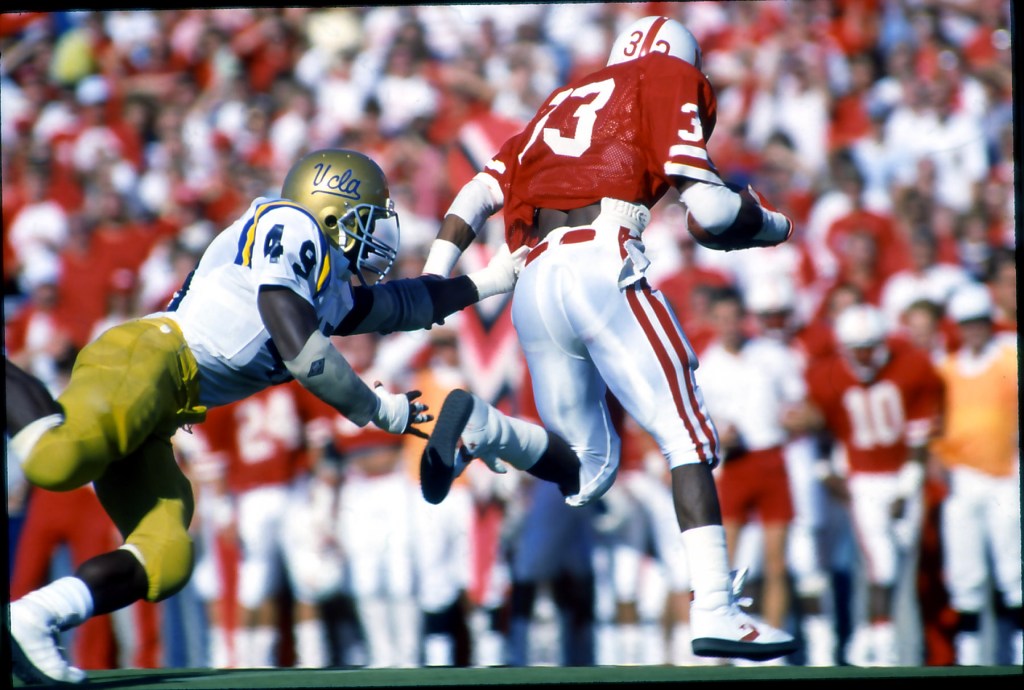

After participating on the freshman scout team, Patton made it into the Bruins’ lineup by his sophomore year. He had put on more than 30 pounds but maintained his speed that set him apart on special teams.

Patton said a career highlight was intercepting a pass in UCLA’s 41-28 win over Nebraska in 1988.

By the time Patton hit his fifth-year senior season, at 6-foot-2 and 222 pounds, teammates nicknamed him “General.” Maybe because they couldn’t get past the Marcus-Marvcus hurdle.

“Marcus, Marvcus, whatever, General Patton is a great success story,” UCLA head coach Terry Donahue would say. “He’s a true model of a player who came from virtually being unknown and worked himself all the way up to the top of the program.”

Marc Dellins, the longtime UCLA senior associate athletic director heading the sports information office, recalled the time when the Bruins played in the 1989 Cotton Bowl at the end of Patton’s junior season. All the players received bolo ties with a plastic replica of the bowl logo. The name spelled on Patton’s tie was “Marvcus,” and Dellins, notcing it, said he could get that fixed and have his name spelled right.

“That’s when he tells me it was spelled correctly,” said Dellins. “I realized for almost two seasons we had been spelling it wrong. I asked him why he didn’t say anything, and he said he didn’t want to make a big deal out of it. I said: ‘That’s your name, you can make a big deal out of it’.”

Actually, when his mother every got annoyed with him, she said she she might call him “MAR-cus.” Normally, it was “Marc.”

During Patton’s senior season, as UCLA stumbled to a 3-7-1 record in 1989 (next-to-last in the Pac-10 and the Bruins’ worst performance in 10 seasons), Donahue noted that Patton “played with great heart and competitiveness. He’s really had a good year despite the fact the team has not. I certainly think on a different team and a different set of circumstances, he’d really receive a tremendous amount of recognition and notoriety for his play.”

Patton set a school record with 22 tackles behind the line of scrimmage. He was third in the Pac-10 in sacks with 11. Teammates named him the co-MVP to go with his political science degree on his resume.

Patton fell to the eighth round of the 1990 NFL draft before Buffalo took a chance on him with the 208th pick overall. Patton said he felt like he was a walk-on all over again.

“When you have that feeling that everyone’s against you and they don’t think you can get it done, it gives you a little extra drive,” Patton said. “I’ve always felt that I had to prove myself.”

Patton not only earned a earned a roster spot but played in all 16 games, then suffered a broken leg on the opening kickoff of the AFC Divisional playoff game against Miami.

A full-time starter by his fourth season as a left inside linebacker, Patton had five seasons in Buffalo, including Super Bowl trips in four straight seasons. Patton got to return to the Rose Bowl as a professional when the Bills played in the Super Bowl XXVII against Dallas and former UCLA teammate Troy Aikman in 1993.

Traded to Washington and moving to middle linebacker, he led the team in tackles three times. He had a career best 143 with 115 solo tackles in 1998. After a Redskins’ 14-point loss to Tampa Bay in 1996, Patton was quoted as saying: “We played like babies. We didn’t tackle. We didn’t chase down people. We let it slip away.”

His final four seasons were in Kansas City, named a team MVP in his first season when he had 135 tackles, after landing a six-year contract said to be worth $10.1 million.

Having an NFL career that spanned 204 games over 13 seasons, Patton never missed a regular season game. Only one other defensive player picked in that 1990 NFL draft — Hall of Famer Junior Seau out of USC, No. 5 overall — played more than the 208 NFL games that Patton did in their career.

At age 35 in his final season with the Chiefs, Patton had two interceptions (giving him 17 for his career) and two fumble recoveries (giving him 12). His scored his only NFL touchdown on a 24-yard interception return in 2000.

He was walking away from pro football right about the same age as his mom did back in her playing days.

The mom’s story

Running back is where Barbara Patton always thought Marvcus would shine in Pop Warner football.

“You’ve got the speed, the moves … running back is the right place for you son,” she would say.

“No, mom,” Marvcus would answer. “I want to play defense … just like you.”

Barbara Patton knew what she was talking about. As 5-foot-4, 130-pound outside linebacker for the women’s professional Los Angeles Dandelions, starting with their debut season in 1973 and going until 1976, she was no shrinking violet. She was a dandy role model.

Continue reading “No. 49: Marvcus Patton (and his mother, Barbara)”