This is the latest post for an ongoing media project — SoCal Sports History 101: The Prime Numbers from 00 to 99 that Uniformly, Uniquely and Unapologetically Reveal The Narrative of Our Region’s Athletic Heritage. Pick a number and highlight an athlete — person, place or thing — most obviously connected to it by fame and fortune, someone who isn’t so obvious, and then take a deeper dive into the most interesting story tied to it. It’s a combination of star power, achievement, longevity, notoriety, and, above all, what makes that athlete so Southern California. Quirkiness and notoriety factor in. And it should open itself to more discussion and debate — which is what sports is best at doing.

The most obvious choices for No. 91:

= Kevin Greene, Los Angeles Rams

= Sergei Fedorov, Anaheim Mighty Ducks

The most interesting story for No. 91:

Dino Ebel, Los Angeles Dodgers coach (2019 to present), Los Angeles Angels coach (2006 to 2018)

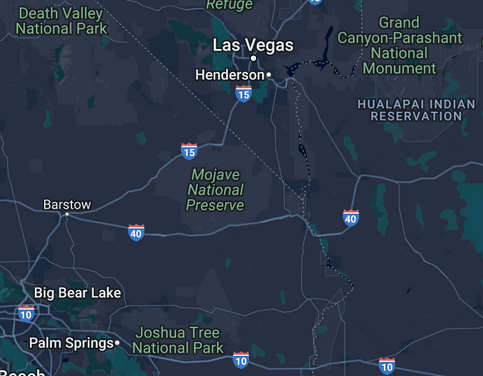

Southern California map pinpoints:

Barstow, Bakersfield, Rancho Cucamonga, Dodger Stadium, Angel Stadium

Barstow, the spunky Mojave Desert city with just enough space for a few key street signals to warn motorists of a major railroad crossings, has become one of the most important pivot points on California’s section of Route 66.

From all points east, where motorists have likely having threaded their way through Needles via the Grand Canyon to get to this 40-square-mile spot, there are three main options toward a mirage of blissfulness. From what’s now called Highway 40, there is: a) go north on the 15 to Las Vegas; b) go south on the 15, eventually hit the 10 and divert to Palm Springs, or c) continue on to the Santa Monica Pier for the end of the Mother Road.

Dino Ebel, neither a dinosaur on a baseball diamond nor in danger of becoming extinct, is Barstow’s representative in every Major League Ballpark when it comes to options heading into third base. Ebel is able, ready and more-than-willing to throw up the stop sign. Or quickly wave someone past him. Flash a sign. Offer a high-five and a pat on the back.

It was calculated that in mid-June of the 2019 baseball season, the Dodgers had put aboard 1,756 base runners. Only six had been thrown out at home plate. If they made baseball cards for third-base coaches, that’s the kind of stats you’d have to work with.

“I honestly haven’t seen anyone better in baseball taking hold of third base,” Dodgers manager Dave Roberts said at the time.

Processing all sorts of data in a split-second of head space — a base runner’s runner’s speed, the arm strength of the outfielder who just took possession of the ball in play, how many outs and which inning we exist in, seeing where are the cut-off men are situated, does this run matter in the grand scheme of the game … That’s just the basics when a ball is in play. Otherwise, it’s communicating to a batter and runner that a hit-and-run play is on. Or a bunt. Or a take. All based on a series of deceptive touching the chest, cap, leg, belt or face.

Risk/reward has no middle ground. Ebel is that experienced gatekeeper. And, ultimately, the communicator. The traffic cop.

For the entirety of the 21st Century, the Dodgers and Angels can thank Ebel for his service. The Dodgers had first claim on him, as an undrafted player out of college, grooming him as a minor-league instructional coach and eventual manager. The Angels borrowed and promoted him for a 15-year run. The Dodgers got him back, and dividends have been paid with two World Series titles.

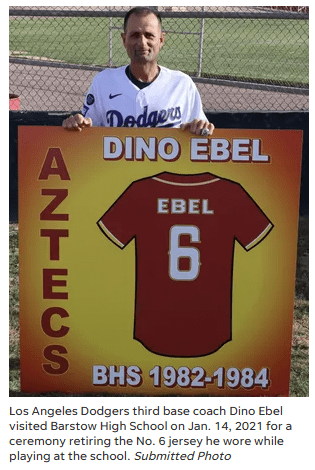

Because of his success, he has been retrofitted as a Barstow landmark. He’s had his enshrinement in the San Bernardino Valley College Hall of Fame in 2012, and his No. 6 retired by the Barstow High Aztecs in 2021. So next time you’re at the outlet mall, trying to find something to do between a trip to the giant In-And-Out or the Motel 6 sleepover, look up the Ebels. He’ll wave you over.

As the co-MVP of the San Andreas League during his senior year in 1984 at Barstow High, Ebel hit .409 with six homers and 19 RBIs as a middle infielder to go with a 7-2 record on the mound and a 2.78 ERA.

After playing for a couple of conference championship seasons at San Bernardino Valley College, where he posted a .295 average, he signed a letter of intent to go to Cal State Fullerton. A transcript review revealed Ebel was one class credit short. At that point, Philadelphia drafted him in the 27th round of the 1986 MLB Draft. Ebel instead diverted to Florida Southern in Lakeland, Fla. There, he was part of the Moccasins’ 1988 NCAA Division II title team, second-team All-American with a .365 batting average

After his senior season, the already multi-tasking second baseman/shortstop/third baseman signed with the Dodgers, undrafted, in 1988. He remembers watching Kirk Gibson’s Game 1 walk-off homer at a friend’s house in Barstow while eating pizza and cheering in his own home with his parents at a time when the Dodgers were to clinch the title over Oakland. Ebel said he already felt like he was a part of the team from a distance as a member of the Dodgers organization.

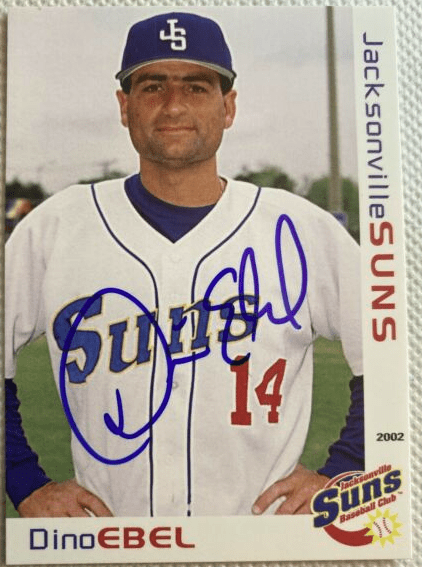

Six seasons in the minor leagues — a Dodgers’ Rookie Gulf Coast League Player of the Year in Sarasota, then at single-A Bakersfield and Vero Beach, double-A San Antonio and reaching two games at triple-A Albuquerque at the end of the 1991 season would be the peak of his playing days. He was in the Dodgers system with future stars such as Pedro Martinez, Mike Piazza and Raul Mondesi.

Ebel was pushed to learn the defensive nuances of every infield position from then-Dodger infield coordinator Chico Fernandez. Ebel learned about instincts and preparation from former Dodger longtime third base coach Joe Amalfitano.

At some point, the 25-year-old Ebel figured out he wasn’t going to get much better than a round-trip ticket back to Bakersfield, even as he played ball in the ’89, ’90 and ‘91 off seasons for the Adelaide Giants of the Australian Baseball League, a Dodger affiliate.

“I didn’t want to bounce around the minor leagues,” Ebel said. “Maybe that dream of getting to the big leagues might have come true, but I said I’m going to buckle down, and if I can’t make it as a player, I’m going to make it as a coach. You set goals for yourself and the goal was, if I’m going to start a coaching career, then the goal was to get to be in a Dodger uniform and be a part of that coaching staff.”

That year, Ebel toured the Dodgers’ farm system as a player-coach for four years. Dodgers farm director Charlie Blaney saw the way Ebel connected with players, serving as a mentor to some.

Ebel moved into full-time coaching for the San Bernardino Spirit (1995) and San Antonio Missions (1996). When Del Crandall resigned in the middle of a 13-game losing streak for the San Bernardino Stampede in ’97, Ebel stepped in and led the team to the championship series.

From 1998 to 2004, Ebel posted a 531-496 record as a minor-league manager in the Dodgers’ system. In that span, the Dodgers’ parent team hadn’t reached a World Series.

Mike Scioscia, the Angels’ manager who knew of Ebel while both were in the Dodgers’ system, added him to his big-league staff as a coach in 2006. Ebel first managed the franchise’s Triple-A Salt Lake (Utah) Stingers (formerly known as the Buzz, known thereafter as the Bees) to a 79-65 mark with a roster that included future big-leaguers Adam Kennedy, Ervin Santana, Joe Saunders, Casey Kotchman, Dallas McPherson and Curtis Pride.

Wearing No. 12 (and later No. 21) in the Angels’ third-base box, Ebel was given free reign to do his work as Scioscia stressed an aggressive, National League type approach on the basepaths. Ebel was also a master at throwing batting practice, fine-tuning the likes of Angels’ Vlad Guerrero and Albert Pujols — eventually pitching to the two when they competed in the annual Home Run Derby during the All Star Game. Pujols even gave Ebel a new blue Corvette for helping him in 2021.

Moving from third-base coach to Scioscia’s bench coach in 2013, Ebel was known for his loud whistle to signal defensive alignments. Back in the third-base box in 2018, that would be his last year with the Angels (as well as Scioscia’s final year as manager). Ebel interviewed for the open Angels’ managerial job, but it was given to Brad Ausmus.

When the Dodgers saw their third-base coach Chris Woodward leave in 2019 to become manager of the Texas Rangers, Ebel got the callback.

“I was so thrilled,” Ebel said, taking back the No. 12. “When I got that call from Andrew Friedman asking me to join their staff, I can’t even explain it, it was exciting for me to just know I’m going to put that Dodger uniform back on and be on that Major League field at Dodger Stadium every day.”

Two World Series rings came Ebel’s way in his first five seasons. He was also back pitching in the 2024 Home Run Derby, trying to help the Dodgers’ Teoscar Hernandez.

Ebel switched to No. 91 after the Dodgers’ acquisition of Joey Gallo in 2022, who wanted to wear No. 12. No Dodgers’ player has ever wore No. 91.

“Dino is one of the best, if not the best, third base coaches in the game,” Roberts said, noting that Ebel has been the U.S. World Baseball Classic coach in 2023 and ‘26. “Working with (Scioscia), what he’s done with the infielders — and he’s done some outfield with the Angels — base running, they’ve been one of the better base running teams in the last decade. His experience, his preparedness and ability to connect with players and teach them.

“He’s very well-versed, a person who’s loyal and was a Dodger, I know he’s thrilled to be back in Dodger blue.”

Ebel, who goes back to Barstow every off season to work with local kids in baseball clinics, is famous for his 30-minute four-mile runs every morning at the gym, followed by a trip to Starbucks for four tubs of oatmeal, a handful of blueberries and walnuts.

The baseball success of Ebel’s sons have also kept him in the news, as he and his wife Shannon have lived in Rancho Cucamonga. Brady and Trey Ebel were a year apart at Corona High, having arrived as a pair from Etiwanda High. At one point in 2023, the two were hitting a combined .720 for the team (13 for 18).

Brady, a left-handed hitting shortstop and pitcher, finished his senior season as a Top 100 prospect for the 2025 MLB draft. At 6-foot-3 and 185 pounds, Brady, who had a commitment to LSU, was picked No. 32 overall in July ’25 by the Milwaukee Brewers, signed, and played in Single A Carolina. Brady was one of three Corona High players picked in the first round — the first time that has happened in the 60 years of the draft history that three from the same high school were chosen.

Trey, a middle-infielder with a commitment to Texas A&M, is closer in size to his father at 5-foot-10 and 165 pounds as he has one more year of high school.

In 2019, Brady and Trey first started tagging along to Dodger Stadium with their dad after the Dodgers hired him away from the Angels. They would take ground balls and shag in the outfield during batting practice before the start of Dodger game.

What sets them from typical high school prospects at draft time is how they were brought up on the big-league fields, on road trips, absorbing experiences and lessons.

“Watching those guys do it every day, just being able to be in the clubhouse and walk around and see how guys act, has helped me and my brother a lot,” Brady said. “I take pieces from everybody.”

“As a dad, I love it, because I get to spend more time with them, and I get to watch them get better,” Dino said. “The process of watching them work with major league players is something I’ll never forget.”

Shohei Ohtani should feel as much as a son to Ebel as his own two.

Ohtani, a rookie with the Angels in 2018 when Ebel coached third base for the team, reunited with Ebel in 2024 with the Dodgers. The two needed to get on the same page quickly.

In Ohtani’s first home game at Dodger Stadium, in his first at-bat, he drove a ball to right field. Ebel had tried to hold him up at second base, but Ohtani kept coming and was suddenly stranded in front of third base — where teammate Mookie Betts was standing. Ohtani assumed Betts would score from first base on the hit, but Ebel held Betts up. There were no outs. Betts at third and Ohtani at second would have provided No. 3 hitter Freddie Freeman with many opportunities.

Ebel, who positioned himself up the third-base line toward home plate, also wasn’t sure if St. Louis outfielder Jordan Walker could make a strong throw to the plate if Ebel was to have sent Betts. Ohtani couldn’t find Ebel in his line of vision, as Ebel was farther up the line, stopping Betts from going home.

“He was like, ‘I gotta learn from this,” Ebel said of Ohtani, after talking to him and interpreter Will Ireton when the inning ended. “He’s always learning. He’s never a guy who is gonna turn away a time to learn. So I thought it was good on his part. And it was good for me, learning again how fast he is.”

It’s always a teachable moment for Ebel.

In the same week Ebel’s son Brady was drafted — and having missed the Dodgers’ final game before the All-Star break in San Francisco to be at home for the draft party — Dino Ebel was with the Dodgers coaching crew in Atlanta dispatched to the MLB All Star Game.

And when that game ended in a 6-6 tie, a new rule went into effect: A three-round “swing off” home-run contest between three hitters from the NL and AL.

Ebel was sent out as the pitcher for the NL team. First hitter Kyle Stowers of Miami managed one homer. But second hitter Kyle Schwarber got three homers in three swings to bring the NL from two down to one ahead. The NL didn’t have to use its last hitter, Pete Alonzo, because the NL built enough of a lead.

Some suggested Ebel be listed as the winning pitcher in the box score.

“What an exciting moment, I think, for baseball, for all the people that stayed, who watched on television, everything,” Ebel said. “That was pretty awesome to be a part of … I had like 10 throws just to get loose. And then it’s like, ‘Let’s bring it on.’ “

In 2022, Ebel got a reminder of how far he had come in his career.

Nearly 40 years after playing Little League Baseball with Ebel in Barstow, Lee Schroeder reconnected with him at a Dodgers-Brewers game in Milwaukee.

“Back in the ’70s, there were two season-ending Little League Tournaments where Dino played for East Barstow and I played for West Barstow, ” Schroeder told the Victorville Daily Press. “It was a great rivalry where our teams fought hard to win. I think we lost in ’77 and they won the following year.

“(After alerting a Dodgers official about their arrival), Dino comes out and says ‘You’re Lee, aren’t you?’” Schroeder said. “I introduced Dino to (my son) Austin, then we chatted for about 10 minutes just like old friends.”

Austin Schroeder said it “was amazing to be in this big ballpark, watching Dino and my dad talking about old times.”

Talking at a Barstow clinic event in 2019, Ebel explained his philosophy as a coach, which also applies to how he views life.

“It’s always been three things for me: Communicate, build the relationship and trust factor,” Ebel said. “Once you get those three things in place and the player knows you care, it just makes it easier. That’s how it’s always been with me.”

That’s where Barstow will get you when you’re connecting dots and directing traffic.

Who else wore No. 91 in SoCal sports history? Make a case for:

Kevin Green, Los Angeles Rams linebacker/defensive end (1985 to 1992)

Best known: En route to a 2016 induction into the Pro Football Hall of Fame, Greene and his long blond locks were a fifth-round draft pick of the Rams (113th overall) in the 1985 selection out of Auburn. A left-defensive end for the Rams, he didn’t earn the first of his 160 career sacks in an ’85 playoff game against Dallas, and didn’t start a game for head coach John Robinson for his first three seasons. By ’88, he led the Rams with 16 ½ sacks, second in the league to Reggie White, with 4 ½ of them coming against San Francisco’s Joe Montana in a key late-season game the Rams needed to win to make the playoffs. In a three-year period from 1987 to 1990, he had 46 sacks, more than any other NFL player in that span, thriving in a Fritz Shurmer five-linebacker defense that highlighted Greene’s speed and pass-rush abilities. The Rams’ change in 1991 to Jeff Fisher as the defensive coordinator moved Green to a right defensive end, and he moved around in 3-4 and 4-3 alignments with only three sacks. His 10 sacks in 1992 got him onto Sports Illustrated Paul Zimmerman’s annual All-Pro team because of the added skills he brought to the Rams with new defensive coordinator George Dyer under new head coach Chuck Knox. But given the chance to become a free agent, he gravitated to the Pittsburgh Steelers in 1993 to return to left outside linebacker. In a 15-year career that included stops in Carolina and San Francisco, with five Pro Bowls and a member of the NFL’s 1990s All-Decade Team, Greene was his team’s top sack leader for 11 of those seasons, retiring third all-time in sacks, plus 23 forced fumbles and five interceptions. Greene died of a heart attack in 2020 at age 58. The Rams offered a statement in that Greene “defined what it means to be a Los Angeles Ram, on and off the field, elevating everyone around him through his extraordinary leadership and commitment to serving others.”

Not well remembered: The 6-foot-3, 247-pounder who grew up in an Army family was in the U.S. National Guard while in college, learning to become paratrooper.

Sergei Fedorov, Mighty Ducks of Anaheim center (2003-04 to 2005-06):

Best remembered: After winning three Stanley Cups, a league MVP award, tw0 Hart Trophies as the league’s best defensive forward and six All-Star seasons during his first 13 years with the Detroit Red Wings, the 33-year-old Fedorov came to Anaheim for a five-year, $40 million agreement, turning down a four-year, $40 million or five-year, $50 million deal to stay in Detroit, according to sources. Fedorov had 400 goals and 554 assists in the bank already. The Russian star was reunited in Anaheim with Ducks GM Bryan Murray, his first NHL coach, just as the Ducks were coming off their first Stanley Cup Final appearance and had lost star left wing Paul Kariya as a free agent to Colorado. Playing with Teemu Selanne and Scott Niedermayer, Fedorov led the Ducks in goals (31) and points (65) his first season, playing 80 games, but Anaheim missed the playoffs. After playing in five games into the 2005-06 season, the Ducks decided to trade him — to Columbus, for Tyler Wright and rookie Francois Beauchemin. The Ducks were already in a salary dump with the new NHL cap in place. Anaheim won the Stanley Cup the next season without him. And after an 18-year career (wearing No. 91 every season) that ended in Washington, Fedorov made it into the Hockey Hall of Fame in 2015 and into into the International Ice Hockey Federation Hall of Fame in 2016.

Not well remembered: Federov became the first Russian to reach the 1,000-point plateau in NHL history, a feat he accomplished while with the Ducks on Feb. 14, 2004, registering an assist against Vancouver.

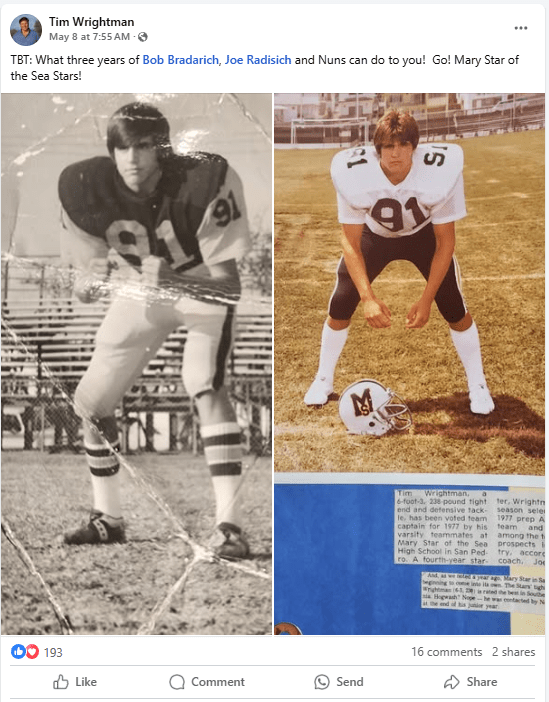

Tim Wrightman, UCLA tight end (1978 to 1981) via Mary Star of the Sea High School in San Pedro (1974 to 1977):

Best known: Inducted into the UCLA Athletic Hall of Fame in 1999, Wrightman, from Mary Star of the Sea High in San Pedro, led the Bruins in receiving in ’79 and was second-all time in the program when he left, logging 73 catches for 947 yards and 10 touchdowns in 44 games. A third-round pick by the NFL’s Chicago Bears, the 6-foot-3, 237-pounder instead went to the USFL’s Chicago Blitz, making him the first NFL draft pick to sign with the upstart league. He eventually went to the Bears in 1985 and was part of their Super Bowl team.

Anyone else worth adding?