The book: “Tom Yawkey: Patriarch of the Boston Red Sox”

The author: Bill Nowlin

How to find it: University of Nebraska Press, 560 pages, $36.95, release Feb. 1.

The links: At Amazon.com, at the publisher’s website.

A review in 90-feet or less: Today’s Boston Red Sox, who visit Anaheim for a three-game series starting tonight facing Shohei Ohtani, have been owned by a group led by John Henry, Tom Werner and Larry Lucchino since 2002. They made a then-record $700 million purchase of the franchise from the Jean R. Yawkey Trust.

A review in 90-feet or less: Today’s Boston Red Sox, who visit Anaheim for a three-game series starting tonight facing Shohei Ohtani, have been owned by a group led by John Henry, Tom Werner and Larry Lucchino since 2002. They made a then-record $700 million purchase of the franchise from the Jean R. Yawkey Trust.

Mrs. Yawkey actually died in 1992 and held a majority ownership of the franchise since 1976.

Before that, her husband, Tom Yawkey was in charge.

So the story goes …

His run started in 1933, when he bought the team for $1.2 million. The Red Sox never won a World Series during his reign, but that’s not why so many pages here are devoted to him.

Nowlin, whom we mentioned earlier this month as the co-editor of the SABR publication about baseball players who made it to Hollywood, isn’t saber-rattling here. We also recognize from many books he has done about Red Sox history, he spares no trees to make his very deep dive in to the Yawkey reign.

But 560 pages worth? It’s 434 pages of chapter reads, plus the epilogue, acknowledgements, notes and index bring up the final 100-plus pages. Because on a project like this, everything must be accounted for.

And, after all, this is the first book ever done on the man, as Nowlin says.

While a lot of this book reminds us of the job Andy McCue did on the Walter O’Malley bio from 2014 — 480 pages deep, also from University of Nebraska Press — it’s needed to help clear the air about some possible false narratives.

For all that was seen and unseen, and for all Yawkey stood for, the topic of racism always becomes an undercurrent.

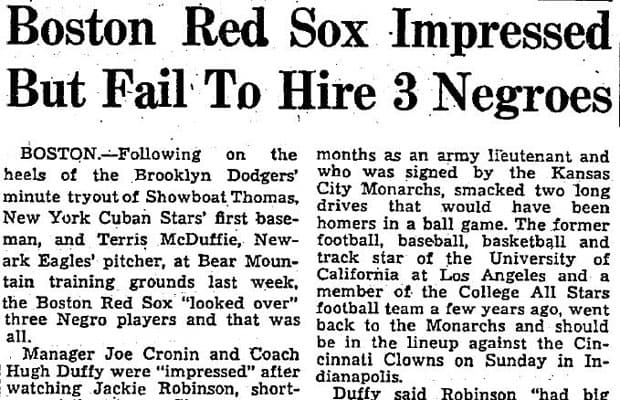

The narrative goes well beyond a note on page 110 where Jackie Robinson is quoted, in 1967, as believing Yawkey was “probably one of the most bigoted guys in organized baseball.” Robinson was one of three black players who had a tryout with the team in 1945, and nothing came of it. Two years later, he was the Dodgers’ Rookie of the Year. And it later came out that the tryout was only partially held to appease the city of Boston so they could hold games on Sundays.

Nowlin address all that in depth and meticulous as he can. He concludes soon that “perhaps Yawkey was not personally racist. Regardless of how one looks at the issue, however, whatever the Red Sox decided, through action or inaction, during the Yawkey years was ultimately his responsibility. … Perhaps far to naively, Yawkey trusted others to do the right thing for him. That trust was sometimes misplaced.”

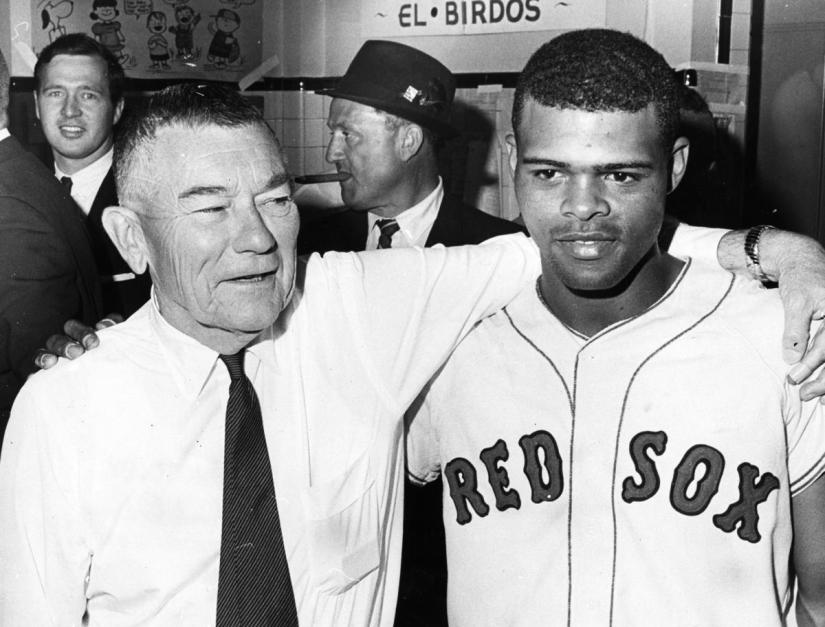

Responsible in the fact that not until 1959 did the team finally have its first black player.

We then traipse all the way to Chapter 27 – pages 420 to 434 – to reach the chapter “Tom Yawkey and Race,” where Nowlin again tries to drain the pool and look at the left-over mildew.

“In an appraisal of Tom Yawkey’s life, it seems unavoidable that we revisit the question of Yawkey and race. The issue keeps cropping up like the proverbial bad penny. Had Tom Yawkey been a racist? There appears to be no conclusive evidence one way or another.”

The topic is picked up again in the epilogue, where Nowlin says there were three key moments in Red Sox history under Yawkey – in ’45, ’50 and ’55.

Then there’s this gem:

“Times change, and organizations change as well. It is worth noting, by way of a postscript of sorts, that the twenty-first-century Red Sox have taken a leading role in honoring Jackie Robinson, hosting an annual education event. The Red Sox Foundation’s contribution to the Jackie Robinson Foundation is perhaps the largest within Major League Baseball. And one can credit the Red Sox with also acting in support of another minority, inviting Jason Collins to throw out the first pitch at Fenway (in 2013, after he came out as gay).

“It is sad to recall this history of the Red Sox and sad to think of what could have been had Tom Yawkey taken actions that were readily available to him. Fortunately other elements of the Yawkey legacy live on today and will for generations to come.”

Listen, there’s a whole book done on this subject some 15 years ago — Howard Bryant’s “Shut Out: A Story of Race and Baseball in Boston,” right after John Henry’s group took over.

Still, that’s an awful lot of pages devoted to decades of damage control. Even somewhat ironic that the cover photo of the book is also in black and white. Add a little color to this story next time, OK?

How it goes into the scorebook: A loud clang off the Fenway Park Green Monster. With Pumpsie Green playing the carom.

How it goes into the scorebook: A loud clang off the Fenway Park Green Monster. With Pumpsie Green playing the carom.

The book to the left: A 32-page children’s book from 2017.

Also:

*A 2017 piece by Art Martone on Yawkey worth looking at.

*A Boston Globe piece on Nowlin’s boom from 2017.

2 thoughts on “Day 17 of 30 baseball book reviews for 2018: No patronizing the Red Sox patriarch, but there’s lots of explaining to do”