This is the latest post for an ongoing media project — SoCal Sports History 101: The Prime Numbers from 00 to 99 that Uniformly, Uniquely and Unapologetically Reveal The Narrative of Our Region’s Athletic Heritage. Pick a number and highlight an athlete — person, place or thing — most obviously connected to it by fame and fortune, someone who isn’t so obvious, and then take a deeper dive into the most interesting story tied to it. It’s a combination of star power, achievement, longevity, notoriety, and, above all, what makes that athlete so Southern California. Quirkiness and notoriety factor in. And it should open itself to more discussion and debate — which is what sports is best at doing.

The most obvious choices for No. 37:

= Donnie Moore: California Angels

= Lester Hayes: Los Angeles Raiders

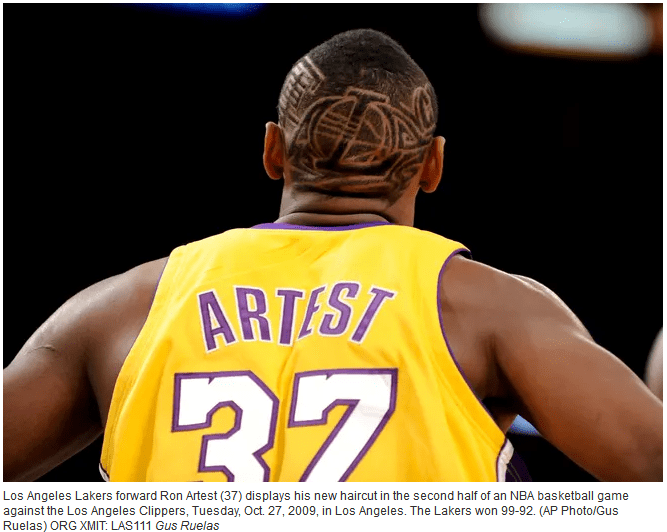

= Ron Artest/Metta World Peace: Los Angeles Lakers

The not-so-obvious choices for No. 37:

= Kermit Johnson, UCLA football

= Bobby Castillo: Los Angeles Dodgers

= Ron Washington: Los Angeles Angels manager

= Tom Seaver: USC baseball

The most interesting story for No. 37:

Tom Seaver: USC baseball pitcher (1965)

Southern California map pinpoints:

Los Angeles (USC), Manhattan Beach, Twentynine Palms

Tom Seaver was a stellar bridge player.

Bridge can be a tricky game. The trick is to gather the least the number of tricks bid by the partnership at the four-person table. The rules seem simple, but mastering the strategy and complexity of it all takes time and practice. Intelligence and patience are rewarded.

During his brief time as a USC student — a pre-denistry major, because he sensed he might need a fallback career — Seaver sometimes could be found with friends hanging out at the 901 Club on Jefferson Blvd., famous for its hamburgers and beer.

And bridge building, when he was there.

In the abridged version of how Seaver went from college baseball to a pro career, there should have been a simple bridge there for him to cross from USC to the Los Angeles Dodgers’ stellar starting rotation of the 1960s.

Instead, there was a toll to pay, and the Dodgers balked.

That’s where Seaver’s poker face came into play. A fantastic 2020 book by acclaimed author and former minor leaguer Pat Jordan revealed how deep a Seaver was. But when it came to his MLB future, Seaver wasn’t bluffing on contract demands. Eventually, both the Dodges and USC lost out.

As the Vietnam War started in 1962, Seaver wasn’t keen on being drafted out of Fresno High, where he just finished his senior baseball season with a 6-5 record but made the Fresno Bee All-City team. Still, he had no pro offers, nor any college interest.

So Seaver enlisted in the U.S. Marine Corps Reserves in 1962 and ’63, with bootcamp at Twentynine Palms. He realized eventually the extra weight and strength he gained in that training allowed him to eventually throw a more effective fastball and slider.

His roadmap to the bigs started with one season at Fresno City College as a freshman, then earning a scholarship to play at USC, the perennial NCAA title team under coach Rod Dedeaux (see SoCal Sports History 101 bio for No. 1).

After Seaver posted an 11-2 mark at Fresno City, the Dodgers were interested. But not more than $2,000 interested. Maybe it was $3,000. That was their reportedly their offer in 1964, the last time MLB teams would have the freedom to sign whomever they wanted before the draft kicked in.

Seaver declined the Dodgers’ gesture and went panning for gold elsewhere.

Dedeaux, who called Seaver the “phee-nom from San Joaquin,” agreed to give him one of his five USC baseball full scholarships — if Seaver first played in Alaska summer ball in ’64. Dedeaux worked out a deal for Seaver to pitch for the Alaska Goldpanners of the Alaska Baseball League, which showcased college talent. The 19-year-old experienced his first Midnight Sun Game in Anchorage — the 10:30 p.m. start on June 21 for the summer solstice that has become part of baseball lore.

In 19 games, starting five, Seaver was 6-2 with a save and 4.70 ERA to go with 70 strike outs in 58 2/3 innings. Later that summer, playing in an National Baseball Congress World Series in Wichita, Kansas, Seaver, now with the Wichita Glassmen, hit a grand slam in a game where he had been called in as a relief pitcher. Seaver would say that was one of his career highlights.

At USC, Dedeaux slotted Seaver as the Trojans’ No. 3 starter – also on the staff was junior Bob Selleck, the 6-foot-6 older brother of eventual USC basketball, baseball and volleyball player and actor Tom Selleck.

During the Trojans’ practices in March, some USC classmates suggested Seaver start lifting weights to increase his upper body strength to match his impressive leg mechanics. That was the start of Seaver’s ultra-effective drop-and-drive delivery. His fastball went up from 85 mph to the mid-90s.

As Bill Madden wrote in his terrific 2020 biography of Seaver, a turning point in Seaver’s career happened in a 1965 USC alumni game. The first batter Seaver faced was Ron Fairly, the Dodgers’ first baseman who been at USC in 1958. Seaver got Fairly out on a weak pop-up with his slider. Jogging back to the dugout, Fairly shouted to Seaver so the scouts nearby could hear: “That was a pretty good pitch, kid!”

The 1965 USC baseball team also included Mike Garrett, not yet the Heisman Trophy winning running back on the football team. Seaver often told a story about the time in baseball practice when he challenged Garrett to step in the batter’s box to take some cuts.

“You’re nothing but a dead-fastball hitter,” Seaver told Garrett, “and that’s all I’m gonna throw you when I face you today. I’m going to strike you out on three pitches.”

Garrett said he was up for it. As Garrett came to the plate, Seaver reminded him: “Remember, only fastballs.”

The first fastball was up and away. Garrett swung and missed. The next fastball was up and in. Garrett swung and missed.

The third pitch was a changeup.

Garrett was so far out in front of it he fell to one knee and couldn’t get up.

“You son of a bitch!” Garrett screamed, pounding his bat in the dirt. Seaver doubled over in laughter.

“Maybe the greatest strikeout of my career — better than Mays, better than McCovey, better than Aaron,” Seaver was said to have told Garrett when they met up at an NFL game between the New York Jets and Garrett’s Kansas City Chiefs in 1969 at Shea Stadium.

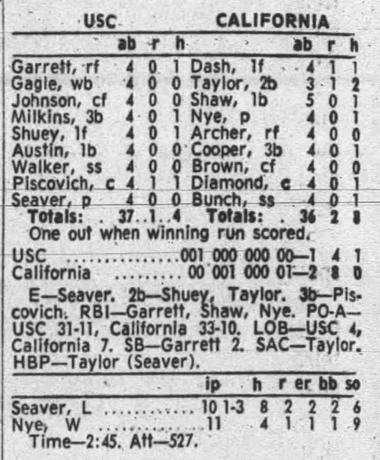

In his one and only season at USC, Seaver stitched together a sophomore season that was highlighted by a 10-2 record, a 2.47 ERA and 100 strikeouts in 105 2/3 innings. It was for a Trojans team that had one of its rare CWS missed appearances.

Consider Seaver’s only two losses:

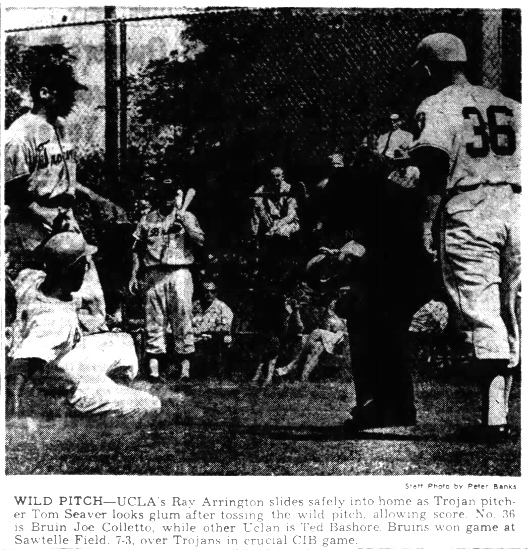

= A 7-3 decision UCLA in April where he gave up one earned run through six innings with four strikeouts. Three walks and an error finally did him in;

= A 2-1 heartbreaker in May at Cal where he went 10 1/3 innings and lost to the Bears in the bottom of the 11th.

Seaver would get his 10th win in a 6-5 decision over Santa Clara at USC’s Bovard Field where he struck out five in 8 2/3 innings. It was USC’s last game of the 30-15 season, but a 9-11 mark in conference kept them out of the NCAA playoffs.

In the summer of ’65, Dedeaux took Seaver as part of a group of USC players to play in Alaska and Hawaii for tournament experience.

By April of that year, the Fairbanks newspapers were already promoting the fact Seaver would be coming back with USC. It mentioned that Seaver had thrown six no-hit innings in an exhibition game against the Pacific Coast League’s Seattle team, an affiliate of the California Angels, and in that game struck out Angels prospect Rick Reichardt twice in the days after Reichardt signed a $200,000 bonus-baby deal with the club.

In the ’65 Midnight Sun Game, USC lost to the Alaska Goldpanners, 4-3. Seaver started for Alaska against his own team. During the contest, Seaver was struck by a line drive and had to be taken to the hospital with a gaping wound to his pitching hand.

As the USC trip progressed, the Honolulu Star-Advertiser ran a story in July about how Seaver and USC polished off the Hawaii Marines, 15-3, to go undefeated and win the Hawaiian Interservice-College baseball tournament.

During that same summer of ’65, MLB history happened. It held its first amateur draft — no more scouts birddogging and overbidding on high school students to sign deals on the day they graduated. The experiences Willie Crawford had with the Dodgers and Kansas City A’s battling for his rights, leading to an outrageous bonus, was part of the call for this draft to happen. (See the post on Crawford for No. 27). The Dodgers gave Crawford a $100,000 contract to join the team right out of Fremont High School.

In the inaugural MLB Draft of ’65, Santa Monica native Rick Monday went No. 1 overall to Kansas City. (See the post on Monday for No. 16).

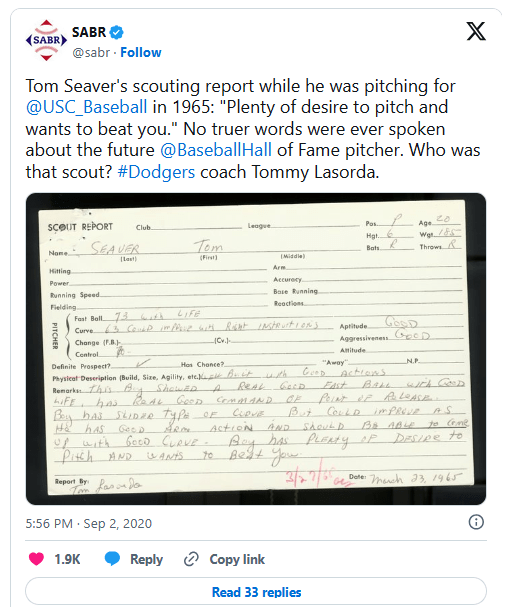

On the advice of scout Tommy Lasorda, the Dodgers picked Seaver. But it wasn’t until the 10th round, number 190 overall.

Lasorda’s scouting report on Seaver (above) included: “Boy has plenty of desire to pitch and wants to beat you.” You can almost hear Lasorda (who has the No. 2 locked up in the SoCal Sports History 101 project) shouting that to the Dodgers’ front office team.

In that ’65 draft, the Dodgers use the first nine rounds to bank on eight players who’d eventually never see an MLB diamond. First was a shortstop named John Wyatt out of Bakersfield High, No. 8 overall. He never made it out of Class A.

Pitcher Alan Foster of Los Altos High in Hacienda Heights (second round) had the most success, lasting 10 MLB seasons, the first four with the Dodgers and one year with the Angels. His MLB debut came in as a 20-year-0ld at the end of the ’67 season and got him on the cover of Sports Illustrated in ’68.

The rest of the Dodgers’ picks from there — catcher Mike Criscione out of Syracuse (third round), outfielder George Mercado out of New York (fourth round), pitcher John Radosevich of West Virginia (fifth round), outfielder Peter Barnes out of Southern University (sixth round), pitcher Gary Griffith out of Anadarko High in Oklahoma (seventh round), outfielder James Johnson out of Las Vegas High (eighth round) and first baseman Paul Dennenbaum of Syracuse (ninth round) — were like Wyatt and never got higher than Single-A.

The only one of the Dodgers’ 30 picks that year (other than Seaver or Foster) to make the big leagues was pitcher Leon Everett (15th round), who made five relief appearances for San Diego after he was taken in the 1969 expansion draft.

Seaver asked the Dodgers to meet his signing offer of $70,000, then reduced to $50,000. The Dodgers were still stuck on $2,000, as Gene Schoor reported in his Seaver biography in 1986. Again, maybe it was $3,000.

In retrospect, yes, the Dodgers’ decision to pick Seaver and then lowballing him was a huge missed opportunity — not just the Dodgers but every other MLB team who passed on him. For what it’s worth, Nolan Ryan was eventually taken in the 12th round of the ’65 draft by the New York Mets.

When the Dodgers balked, wanting more control of the situation, Seaver put his cards down and left the table.

“When I asked for $50,000, I think they laughed,” Seaver wrote in his 1973 book “Baseball Is My Life,” at the height of his Mets career. “They thought half of that was too much.”

Imagine a Dodgers rotation in 1966 that perhaps could have had Sandy Koufax, Don Drysdale, Don Sutton and Tom Seaver.

On Jan. 29, 1966, seven months after Seaver turned down the Dodgers, the Atlanta Braves, which had just relocated to Georgia from Milwaukee, took Seaver in this new Secondary Phase January Draft,number 20 overall. The Dodgers had the 14th pick of that draft. They passed on Seaver and took USC pitcher John Herbst, who never got out of Single-A.

Atlanta offered the 21-year-old Seaver a $50,000 package — a $40,000 signing bonus, $4,000 for his college scholarship and $7,000 if he reached the Major Leagues. Braves general manager John McHale had called Seaver “the best pitching prospect on the West Coast.”

So on Feb. 24, Seaver signed.

However …

Just prior to the signing, Seaver played for USC in what he thought were exhibition games against Cal Poly and San Fernando Valley State. They were in fact part of the USC official schedule. The Dodgers, according to reports, saw this and brought it to the attention of the Office of the Commissioner. Not that they sought some kind of revenge or anything for Seaver’s previous rebuke.

Seaver had been assigned to the Braves’ Triple-A Richmond roster in the International League affiliate, and a locker with his name was ready for him at the Braves’ spring training camp in West Palm Beach, Fla., with his name and the No. 65.

Then Major League Baseball stepped in. On March 2, General William D. “Spike” Eckert, just elected baseball’s fourth Commissioner less than six months earlier, spiked Seaver’s contract with the Braves.

Eckert cited the league rule that a college player couldn’t sign if his intercollegiate season had already started. Those two non-exhibition games mattered. Eckert ruled Seaver’s signing was a violation of the rule, fined the Braves $500 and banned them and their affiliates from signing the Seaver for the next three years.

Atlanta was prepared to tear up the contract and allow Seaver to finish his college career, retaining his rights. USC athletic director Jess Hill had already contacted the NCAA and demanded Seaver must be declared ineligible. This was as USC had already been slapped with NCAA sanctions in 1959 and feared more retribution for its success.

The Catch 22 here: Seaver went back to USC, but he wasn’t allowed to play. The NCAA ruled Seaver ineligible to pitch for the Trojans because he signed a pro contract, even though it was now void. But he couldn’t play for the Braves.

Seaver petitioned Eckert to change his mind, and his father threatened to sue. Finally, Seaver got on the phone with the Commissioner’s aide, future American League president Lee MacPhail, to plead his case. Eckert eventually declared that, while the Braves still couldn’t have Seaver, any other team could. So every MLB club had until April 1 to submit a notice that they would match the Braves’ offer to Seaver. Those teams would be entered into a lottery and a team would be drawn to get the rights to Seaver, at the price of his original deal with Atlanta.

Only three teams entered the Seaver sweepstakes: Cleveland, Philadelphia and the New York Mets.

The Dodgers? General manager Buzzie Bavasi told the Long Island Press’ Jack Lang in 1967 that he was having his own trouble with Koufax and Drysdale holding out for bigger contracts at that time, otherwise, maybe, they would have rejoined the scramble to re-engage with Seaver. Again, the investment in Crawford a few years earlier may have made them a bit shy about digging into their budget for one player.

The Mets became the lucky team picked out of a hat. Seaver signed with the beleaguered franchise on April 3, 1966 for their investment of $51,100. That summer, the Dodgers ended up giving Koufax a $125,000 deal and gave Drysdale a $110,000 payout. Koufax lasted one more year before he retired; Drysdale pitched just four more.

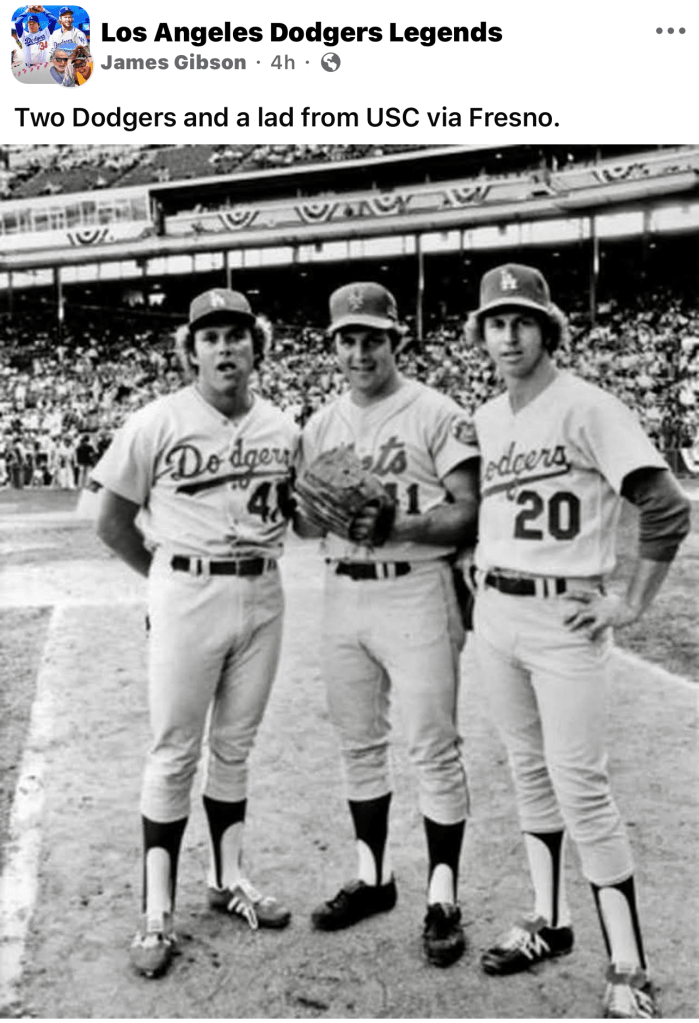

Seaver wrote in his book: “I was interested in the Los Angeles Dodgers, the San Francisco Giants, and Bad Henry Aaron with Atlanta. I couldn’t have cared less about the 10th-place team they called the Amazing Mets. I just never dreamed of playing in New York.”

Seaver wasn’t finished with USC. He had been courting Nancy McIntyre back in his Fresno High days, and both were at Fresno City College in 1964. While at USC in 1965, Seaver reportedly called her every other day.

“What are the girls like there,” Nancy asked about the USC co-eds.

“Nothing like you,” Tom would reply. “They’re boring. All they want to do is party and shop for clothes.”

They married in June of 1966.

Seaver made his MLB debut in April of 1967. In his third start, to get his second win, Seaver threw the first of his 231 complete games — a 2-1 decision over the Chicago Cubs at Wrigley Field. The New York Daily News’ Dick Young wrote: “Tom Seaver, the kid picked out of a hat by Commissioner Eckert, thus making the commissioner the best scout the Mets have …”

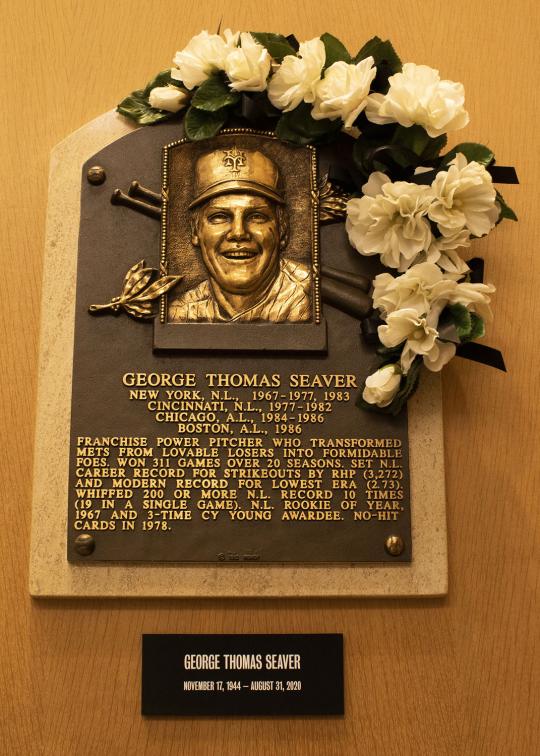

He was a 22-year-old All Star, starting a 20-year MLB season that would bring three Cy Young Awards (plus a second-place finish in the 1969 NL MVP voting), five strikeout titles, three ERA titles, 12 All Star selections and a 1992 Hall of Fame induction with 98.8 percent of the vote on the first year of eligibility. At that time, no player ever received a higher approval rating by the Baseball Writers Association of America.

Seaver did come back to haunt the Dodgers, as well as the other dozen teams in the National League.

The first two times Seaver faced the Dodgers, in May and August of 1967, both were complete game wins at Shea Stadium. On June 10 of 1968 — two days after Don Drysdale set the MLB consecutive scoreless inning streak — Seaver threw all 10 innings in a 1-0 win at Dodger Stadium against Don Sutton. Seaver had a second complete-game win at Dodger Stadium that August as well, again over Sutton.

During the “Miracle Mets” 1969 title run, Seaver faced the Dodgers twice in June and beat them both times — the first sending heralded Alan Forster to an 0-4 record. Seaver beat the Dodgers 22 times in his big-league career with 17 complete games and four shutouts.

“It sounded so simple,” Seaver wrote about his career. “Simple, all right, except that it turned out to be as complicated a stew as I could imagine. I’m sure somebody in the Atlanta organization thinks about it every time I win a game. Possibly the Dodgers, too.”

Seaver and one-time Fullerton High star Walter Johnson are the only major-league pitchers with 300 wins (311 total), 3,000 strikeouts (3,640 total) and a sub-3.00 ERA (2.86). Seaver, who wouldn’t retire until age 41 in Boston in 1986, had returned to USC to get a communication degree in 1974. He was USC’s first player to make the Baseball Hall of Fame and was inducted into the USC Athletics Hall of Fame in 1995, its second-ever class.

After his playing days ended, Seaver showed his expertise and intelligence — and communication skills — as a heralded network TV analyst.

When Seaver died of COVID in 2020 at age 75 in Napa, where he established a wine-making business that ran close to California Highway 37, his USC friends and family came forward to honor him.

“Growing up in Southern California, Tom was a childhood idol to me and many other kids in my era,” said then USC head baseball coach Jason Gill. “He was a great example of what talent, hard work and passion for the game of baseball and life looked like for all of us. Tom represented the Trojan Way and carried himself like a champion always.”

Tom House, Seaver’s USC teammate and picked by the Chicago Cubs in that 1965 draft just 11 spots after Seaver, said: “Obviously, his career and legend belongs to big league baseball. But, on the back side, he was a very private person and being part of the SC family allowed a consistency of interaction and communication that few people saw. He was really a bright person. Committed to baseball but also family was huge to him. And to be part of the SC family and to be part of the big league baseball arena, was a blessing for me.”

Justin Dedeaux, teammate and roommate of Seaver’s in 1965 and son of the late Rod Dedeaux, added:

“We were fortunate enough to stay in touch through the years. I’d visit him up in Napa, and during the seasons when he was pitching, my dad and I would go out and see him every chance we got and go out to dinner with him after the games. I know my dad really cherished that relationship. I just can’t say enough about what a wonderful human being he was. He was very loyal to the program, he would come out and talk to our pitchers and stay involved. Tom was just one of those guys who did things the right way his entire life. He had a wonderful marriage to Nancy, beautiful daughters, and just a great life. I’m very thankful to have been a part of it and I know Trojan fans are grateful for the way he represented the university.”

In Bill Maddon’s biography, Seaver is quoted: “I learned more in one year at USC under Coach Dedeaux than I would have in two or three seasons in the low minors. Most of all I learned concentration and to stay in the game mentally.”

Kind of like how one masters the game of bridge.

The only other instance in MLB history when a commissioner stepped in to orchestrate the signing of a player other than Seaver was in 1979. It involved another USC pitcher that somehow Trojans coach Rod Dedeaux helped orchestrate a better outcome for one his players.

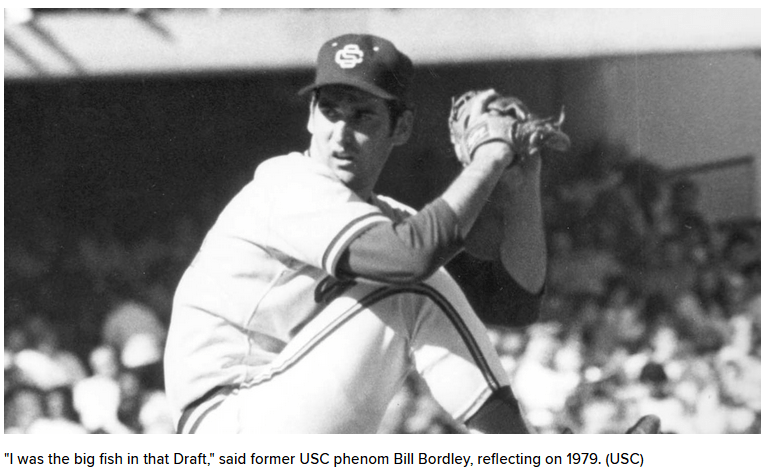

As a first-team All-American in 1977 and ’78 — the only Trojan ever to accomplish the feat — 6-foot-3 left handed fireballer Bill Bordley (wearing No. 49) went 14-0 as a sophomore and 12-2 as a junior, winning the decisive game for USC over Arizona State in the College World Series to clinch a national title. Bordley was a phenom years earlier at Bishop Montgomery High in Torrance (while wearing No. 24) and made it into Sports Illustrated’s “Faces in the Crowd” segment in July of 1975 as a junior. He he led the Knights to the CIF-Southern Sectional 3A title at Dodger Stadium, winning all five playoff games and pitching 35 straight innings without giving up an earned run. He was also the CIF Player of the Year also as a senior — in his career he completed 14 of his 17 starts, winning 16, with 176 strike outs over 115 2/3 innings.

Bordley had told all the MLB teams prior to the 1976 Draft that he wanted to stay on the West Coast because his father was in poor health. He thought the Angels would take him with its No. 6 overall choice, but Milwaukee stepped in at No. 4 and claimed Bordley. Bordley passed, and went to El Camino College for a season, then gravitated to USC for his two spectacular seasons. Prior to the 1979 January draft, Bordley left USC and declared himself eligible because of family hardships and made it clear again he was only going to play on the West Coast. Yet, in that January secondary phase of the draft, Cincinnati took him with the third pick, just before the Angels’ fourth choice, and the Angels were later penalized for tampering with Bordley. When Bordley refused to sign with the Reds, commissioner Bowie Kuhn voided the pick, put the names of the five teams Bordley would be willing to play for in a hat, and San Francisco was picked. That meant the Giants had to give him at least a $100,000 bonus as a 20-year-old.

After a full season at Triple-A Phoenix (8-11, 4.56 ERA, 94 walks and 84 strikeouts in 156 innings), plus 19 more games the next, the Giants finally brought Bordley up in June of ’80. He lasted just eight games, starting six, posing a a 2-3 record and 4.70 ERA. His elbow gave out on him and he underwent Tommy John surgery the following season. “I was the fourth player to have the surgery,” Bordley said.

After surgery and sitting out 1981, he came back in at Single-A Fresno at age 24 and wasn’t effective. He tried pitching in Mexico in ’82 and didn’t last long. A comeback try with Atlanta — the team that originally thought it had Seaver — didn’t pan out and Bordley retired in 1983.

At age 25, Bordley went back to USC, got a business degree and worked his way into the Secret Service during the Clinton administration starting in 1988. He was stationed at the Los Angeles office. Bordley eventually went to work as vice president of security and facility management for Major League Baseball, working out of New York.

When Bordley was inducted into the College Baseball Hall of Fame in 2014 he said of his time at USC: “It almost felt like a downgrade when I went to the big leagues (compared to) things we did with coach Dedeaux. He put so much confidence in you. I’m sure people might have known Xs and Os better, but his ability to make you feel like King Kong and how to win.”

One more note: In Bordley’s MLB debut for the Giants on June 30, 1982, a Monday night game at Candlestick Park before just 5,700 fans, Bordley was credited with the win in an 8-4 decision over Cincinnati, leaving with a 6-3 lead after six innings. The Reds’ starter and losing pitcher: Tom Seaver. Bordley got his one and only MLB hit also in that game against Seaver in the fourth inning, a single up the middle.

Who else wore No. 37 in SoCal sports history?

Make a case for:

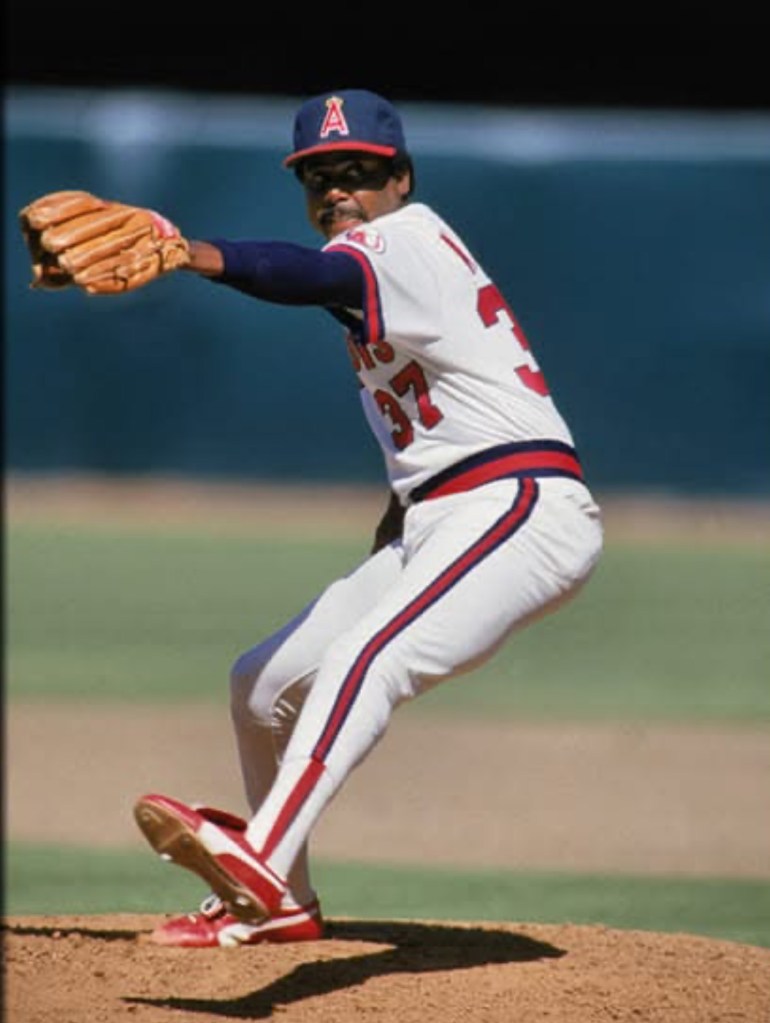

Donnie Moore: California Angels relief pitcher (1985 to 1988):

In a 2011 piece from The Atlantic magazine titled “The Myth of the Home Run that Drove an Angels pitcher to Suicide,” coming out 25 years after Moore took his own life at age 35 in 1989, writer Kevin Baker starts:

“There are stories we like to tell ourselves about sports. One of them is that the games we play can be so engrossing, our losses so exquisitely painful, that we can never really recover from them. This is mostly a fan’s way of looking at things, of course. Players can’t afford such thoughts. Their business is to shake it off, forget about even the worst losses, and move on to the next game. Yet as fans, we continue to believe that we can impose our agonies upon them, that we can so hound them with their mistakes and failures that they can never escape them …

“Donnie Moore, a pitcher for the California Angels who, unable to overcome his own moment of failure, was supposedly driven to take his own life. Yet the chances are good that everything you think you know about his story is wrong.”

Moore had been the Angels’ team’s lock-down reliever for 155 games in four seasons, including an AL All Star appearance in ’85 when he saved 31 games with a 1.92 ERA. A year later, when he gave up a go-ahead home run to Boston’s Dave Henderson in Game 5 of the 1986 American League Championship Series at Anaheim Stadium, Moore took the blame for not only that, but the Angels’ eventual seven-game series loss to the Red Sox.

Henderson’s home run was neither a walk-off nor a series-ending. It just felt that way to Moore.

Earlier that season, Moore missed a month with what was diagnosed as a muscle strain in his rib cage, but eventually found to be a bone spur near his spinal cord. Throwing awkwardly, he found his elbow and shoulder aching. He took a nerve-blocking agent for the rib cage, anesthesia and cortisone for his shoulder, and other medications for the migraines that had begun to plague him. Despite all that, he saved 21 games in ’86 as the Angels won the AL West.

In Game 5 of the AL Championship Series against Boston, the Angels’ Mike Witt took a 5-2 lead into the ninth inning, one win from the World Series. After a lead-off single to Bill Buckner, Witt struck out Jim Rice. When Don Baylor golfed a Witt curveball over the fence in left-center, the Angels’ lead became 5-4. Witt got Dwight Evans to pop out to third for the second out.

To finish the game, Angels manager Gene Mauch pulled Witt in favor of left-handed reliever Gary Lucas to face left-handed hitting Rich Gedman, who homered off Witt earlier. Lucas hit Gedman square on the forearm with the first pitch, the first batter he had hit in more than 400 innings over four seasons.

Mauch went back out and brought in Moore.

Henderson, batting just .189 in the championship series, already struck out in a key situation earlier that afternoon. Moore got two strikes on Henderson and nearly struck him out with a split-fingered fastball, but it was weakly fouled off. Catcher Bob Boone called for an off-speed splitter. Moore threw it, but the ball had no snap. Henderson hit it eight rows deep in the left field stands, then danced around the bases as the Red Sox took a 6-5 lead.

The Angels fought back to tie the score again in the bottom of the ninth, and then loaded the bases with just one out, but neither Doug DeCinces nor Bobby Grich could push the winning run across.

Moore, running on fumes, gave up two hits in the top of the 10th inning, but got Rice to hit into a double-play. In the bottom of the 10th, the Angels threatened again — only to see Rice, never known for his fielding, make an outstanding, two-handed catch against the wall.

In the top of the 11th, Moore was still pitching. He hit Baylor with a pitch. Evans singled to center. Gedman bunted them to second and third. Henderson was back up. He hit a long, high fly to center field — a sacrifice fly to score Baylor. After Moore got backup shortstop Ed Romero to fly out to left, Mauch replaced Moore with Chuck Finley, a left-hander, to get Wade Boggs to ground out. The Angels went quietly in the bottom of the 11th.

Moore had pitched two innings, faced 11 batters, and took the loss. He took the loss hard.

Even as the series went back to Boston’s Fenway Park, the Red Sox cruised to Games 6 and 7 wins by the scores of 10-4 and 8-1. The Angels played as if they were shell-shocked. Moore pitched the final inning of the season for the Angels, a 1-2-3 eighth inning in Game 7, which began with getting Henderson to fly out to center.

“Maybe if I had tried to blow it past (Henderson), we’d be drinking champagne right now,” Moore told reporters after the Game 5 loss. He did admit in the clubhouse that afternoon: “Every time I throw, my arm hurts … that’s not why I lost the game. I was horseshit.”

After the Game 7 loss in Boston, Moore also said: “I’ll shoulder the blame. Somebody’s got to take the blame, so I’ll take it … I threw that pitch. I lost that game.”

Moore had doctors remove the spur near his spine that had been tormenting him. Mauch retired after spring training 1988 after 26 seasons without a pennant. The Angels cut the 34-year-old Moore loose by the end of the ’88 season after he made 27 appearances, logged four saves and had a 5-2 record despite a 4.91 ERA in 33 innings.

In the summer of ’89, the Royals released him from their Triple-A team in Omaha, ending his baseball career at the age of 35. On July 18, 1989, less than a week after his release, Moore shot himself in the head with a .45.

The instant assumption was that he killed himself because of a home run.

“I think insanity set in. He could not live with himself after Henderson hit the home run. He kept blaming himself,” said Moore’s agent, Mike Pinter. “That home run killed him.”

Tom Boswell in the Washington Post lamented “an American predisposition with Puritan roots … to equate defeat with sin,” and asked that “before we boo or use words like ‘choke’ and ‘goat,’ perhaps we should think sometimes of Donnie Moore.”

As Baker wrote in The Atlantic story, Tonya Moore, Donnie’s wife with him since high school, knew her husband was violently jealous and possessive. She said Moore started beating her when she was 19 years old, and kept it up through the rest of their years together, especially when he had knocked back too much Jack Daniels.

Well before Game Five of the 1986 American League Championship Series, he would become enraged whenever she so much as looked at or talked with another man. It was a side of him that he didn’t allowed his teammates or the sportswriters to see — or perhaps no one wanted to look very hard.

Baker wrote that Tonya tried to leave her husband when his baseball career ended, knowing he would become still more violent. When a brief attempt at a reconciliation failed, he chased her around their beautiful home with his gun, shooting her through the neck, lungs, and chest in front of their three children. Somehow, Tonya made it to the backseat of her car, and her 17-year-old daughter drove her to an emergency room. Tonya survived, but didn’t necessarily fully recover. Back at home with his young sons, Donnie Moore put the .45 to his head and pulled the trigger as they watched.

In 2012, Sports Illustrated put out a story by Michael McKnight headlined: “The Split: Twenty-Five Years After Donnie Moore’s Death, It’s Time To Dispel the Myth That The Pitcher Killed Himself Because Of A Playoff Home Run. The Truth is Both Darker and More Relatable.” In the 1990 issue of GQ, a story ran called “What Broke Donnie Moore?”

On July 30, 1989, days after Moore’s suicide, Ira Berkow wrote for the New York Times under the headline “Donnie Moore and the Burdens of Baseball” these words:

”It’s never just one thing that precipitates suicide,” said Loren Coleman, a research associate with the Human Services Development Institute of the University of South Maine. Coleman has made a study of suicides, including the 77 major leaguers or former major leaguers who have done it. ”It’s invariably a number of interwoven factors.” In Moore’s case, he had only a month before been released by the Omaha Royals; Moore’s agent had filed a grievance saying Moore owed him $75,000 in commissions; Moore had marital problems, and he had talked about selling his house.

The story recalled how Bruce Gardner, an all-America left-handed pitcher at USC in 1960, rose to Triple A for the Los Angeles Dodgers before he was released at age 25 back in Single-A. He was unsuccessful in business ventures and had unhappy romances. He became a high school baseball coach. Failure plagued him. One night in 1971, Gardner climbed the fence of the locked up Dedeaux Field on the USC campus, went to the mound, and shot himself in the head. He wrote in a suicide note:

”I saw life going downhill every day and it shaped my attitude toward everything and everybody. Everything and every feeling that I visualized with my earned and rightful start in baseball was the focal point of continuous failure. No pride of accomplishment, no money, no home, no sense of fulfillment, no attraction. A bitter past, blocking any accomplishment of a future except age. I brought it to a halt tonight at 32.”

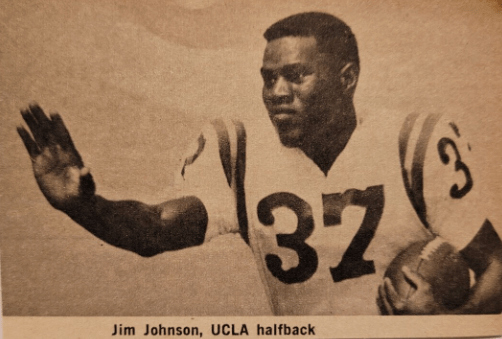

Jim Johnson, UCLA wing back/defensive back (1959-1960):

The younger brother of UCLA athletic legend Rafer Johnson also ran track in Westwood – winning the NCAA 110-meter hurdles. Jimmy piled up 812 yards from scrimmage (543 rushing) and four touchdowns in his career and was a first-round pick of the San Francisco 49ers in 1961. In a 16-year NFL career, he was a four-time All-Pro as a defensive back and a receiver. He was inducted into the UCLA Athletics Hall of Fame in 1992, and the Pro Football Hall of Fame two years later.

Kermit Johnson, UCLA running back (1971 to 1973):

A member of perhaps the best high school team ever in Pasadena at Blair High in 1969 with James McAlister, the two went as a package deal to UCLA and became celebrities for Pepper Rogers’ Wishbone offense. Johnson was 10th in the 1973 Heisman voting after piling up 1,129 yards and 16 touchdowns his senior year, where he broke the school record averaging more than 7.5 yards per play (eventually surpassed by quarterback Cade McNown 34 years later). Johnson and McAlister also gravitated to the WFL’s California Sun for a year. Johnson then played two years with the NFL’s San Francisco 49ers.

Lester Hayes, Los Angeles Raiders defensive back (1982 to 1986):

Also in Oakland from 1977 to 1981, Hayes ended up in five Pro Bowls, three with L.A. A key member of the Raiders Super Bowl XV and XVIII championship teams, Hayes’ 39 interceptions are tied with Willie Brown’s mark for the all-time team record. And where would the term “Stickum” be without Hayes? The substance by that name was banned from the NFL in 1981, directly linked to his usage to give himself a better grip of the ball in his hands. His nickname was “The Judge” and “Lester the Molester” because of the way he covered receivers, starting from a low crouch.

Ron Washington, Los Angeles Angels manager (2024 to 2025): Having managed the Texas Rangers from 2007 to 2014 to four straight 90 win seasons and two AL pennants, Washington had to step away to clean up his personal life. Washington returned to the game as Atlanta Braves coach and became the Angels new manager to start 2024. In June of ’25, Washington had to step down for health reasons. Perhaps a little remembered fact: He wore No. 44 during a short time as a Los Angeles Dodgers rookie in 1977 (10 games, 20 at bats).

Bobby Castillo, Los Angeles Dodgers pitcher (1977 to 1981, 1985): Out of Lincoln High in East L.A. and L.A. Valley College, Castillo first joined the Dodgers wearing No. 41 on the NL-pennant-winning teams of ’77 and ’78. His greatest contribution: Teaching the screwball to rookie Fernando Valenzuela, the eventual 1981 Cy Young Award winner. Castillo was part of the Dodgers’ 1981 World Series bullpen before the Dodgers traded him to Minnesota. In 2006, Castillo made the acceptance speech for Valenzuela’s entrance into the Baseball Reliquary’s Shrine of the Eternals. “I’m still finishing up for him,” said Castillo, who died of cancer at age 59 in 2014.

Mike Davis, Los Angeles Dodgers outfielder (1988 to 1989): Because he drew a rare walk against Oakland’s Dennis Eckersley as a pinch hitter for No. 8 hitter Alfredo Griffin with two out in the bottom of the ninth during Game 1 of the 1988 World Series, the game was prolonged so Kirk Gibson could pinch hit for Dave Anderson, who had been in the on-deck circle to pinch hit for Alejandro Pena. Then Davis stole second on a 2-2 pitch. Gibson could have been called for interference when catcher Ron Hassey attempted to throw down to second, but halted. That took away a force out and made it able for Gibson to tie the game with a single — Gibson said he did change his approach at that point to just trying to get a base hit. He hit a homer instead. Game over. Davis hit a two-run homer of A’s reliever Storm Davis in Game 5.

Darren Dreifort, Los Angeles Dodgers pitcher (1994 to 2004): A five-year, $55 million contract signed in 2000 will be Dreifort’s comfort blanket. A Dodgers bonus baby in the early ’90s, he missed the entire 1995 season, battled persistent arm issues, and had a 39-45 record prior to reaching free agency. His agent was Scott Boras, who hinted Dreifort was about to sign with the rival Colorado Rockies. So Dreiford stayed, got the deal, had a 5.13 ERA in 16 starts in 2001, missed all of 2002, had elbow reconstruction surgery and doctors said he suffered from a degenerative tissue condition and a deformed femur, which threw off his mechanics and shattered his durability.

Quintin Lake, UCLA football defensive back (2017 to 2021); Los Angeles Rams defensive back/safety (2022 to present): The Mater Dei grad played five seasons with the Bruins, where he had 180 tackles and six interceptions, and had the identity of the son of UCLA linebacker, Carnell Lake (who wore No. 31) and was inducted into the school’s Athletic Hall of Fame in 2000. During Carnell Lake’s 12-year NFL career, primarily in Pittsburgh, he wore No. 37 — which his son, Quintin, took to heart at UCLA and with the Los Angeles Rams, who drafted him in the sixth round of the 2022 selection, and eventually converted him to safety. He led the Rams with 73 solo tackles in 2024.

Have you heard this story:

Ron Artest/Metta World Peace, Los Angeles Lakers forward (2009-10 and 2015-16 to 2016-17):

This can get complicated.

He spent two stints with the Lakers, wearing No. 37 when he joined as a free agent, age 30, in 2009-10. He claimed he wore it in honor of Michael Jackson, who died in 2009, as that was the number of weeks Jackson’s “Thriller” was No. 1 on the charts. He has also said that when he signed his name and included the number “37” it looked to him like the “3” was an “M” for Michael and the “7” was a “J” for Jackson and his spin dance move.

That’s when his name was Ron Artest. He changed it to Metta World Peace in 2011, and also eventually changed to No. 15.

He became Metta Saniford-Artest in 2020, after he played his last game with the Lakers in 2017. Somewhere in there, he was also known as The Panda’s Friend. Legally.

As many can attest concerning Artest, it hasn’t been easy also following someone around who also wanted to be called Tru Warrior, Ron-Ron and Beast.

When he came to the Lakers, it was with plenty of baggage – didn’t the Lakers learn anything from Dennis Rodman? There was “The Malace at the Palace” when he played for Indiana. His career started in Chicago, and also veered through Sacramento and Houston, where his uniform number varied from No. 15 to 23 to 91 to 93 to 96 and even 51 in New York.

But he was given the J. Walter Kennedy Citizenship Award in 2011. During his final season with the Lakers in 2017, he said he tried to change to No. 60, in honor of the 60 points Kobe Bryant scored in his final game the previous spring. However, the change was too late after the league’s deadline had passed.

His most memorable moment as a Laker when he hit a clutch 3-point shot in the closing moments of the Lakers’ win over Boston in the 2010 NBA Finals. That was the last game he wore No. 37.

Mike Kekich, Los Angeles Dodgers pitcher (1965, 1968):

This can also get complicated.

As a 20-year-old left-hander, Kekich was valuable enough to be specialist reliever as part of the Dodgers’ 1965 World Series roster against Minnesota. He had made five appearances at the end of that ’65 season — which Vin Scully once recalled that Kekich was the first player he ever saw ejected from an MLB game before the player had ever made it into a game, tossed for heckling while on the bench.

Although Kekich won 21 games while playing at three different minor-league levels in the organization in 1967, his Dodgers’ career MLB totals were a 2-11 record and 4.38 ERA in 30 games. He was traded to the Yankees in the 1968 offseason for outfielder Andy Kosco.

That trade didn’t make as big a headlines as the trade he was involved with in 1973. Kekich was traded by his wife, Susanne, for Yankees teammate Fritz Petersen. Kekich then joined Peterson’s former wife, Marilyn. Yes, they essentially traded families. Kekich did not last as long with Marilyn as Petersen did with Susanne.

We also have:

Teoscar Hernandez, Los Angeles Dodgers outfielder (2024 to present)

Ed Robuck, Los Angeles Dodgers pitcher (1958 to 1963)

Norm Sherry, California Angels manager (1976 to 1977). Wore No. 34 as a Los Angeles Dodgers catcher from 1959 to 1962.

Anyone else worth nominating?

1 thought on “No. 37: Tom Seaver”