This is the latest post for an ongoing media project — SoCal Sports History 101: The Prime Numbers from 00 to 99 that Uniformly, Uniquely and Unapologetically Reveal The Narrative of Our Region’s Athletic Heritage. Pick a number and highlight an athlete — person, place or thing — most obviously connected to it by fame and fortune, someone who isn’t so obvious, and then take a deeper dive into the most interesting story tied to it. It’s a combination of star power, achievement, longevity, notoriety, and, above all, what makes that athlete so Southern California. Quirkiness and notoriety factor in. And it should open itself to more discussion and debate — which is what sports is best at doing.

The most obvious choices for No. 8:

= Kobe Bryant: Los Angeles Lakers

= Troy Aikman: UCLA football

= Steve Young: Los Angeles Express

= Drew Doughty: Los Angeles Kings

The not-so-obvious choices for No. 8:

= John Roseboro: Los Angeles Dodgers

= Tommy Maddox: Los Angeles Xtreme

= Ralphie Valladares: Los Angeles Thunderbirds

= Teemu Selanne: Mighty Ducks of Anaheim

The most interesting story for No. 8:

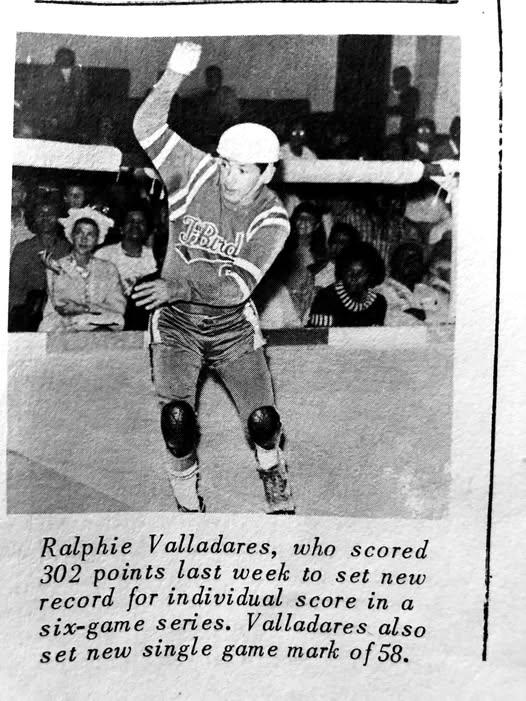

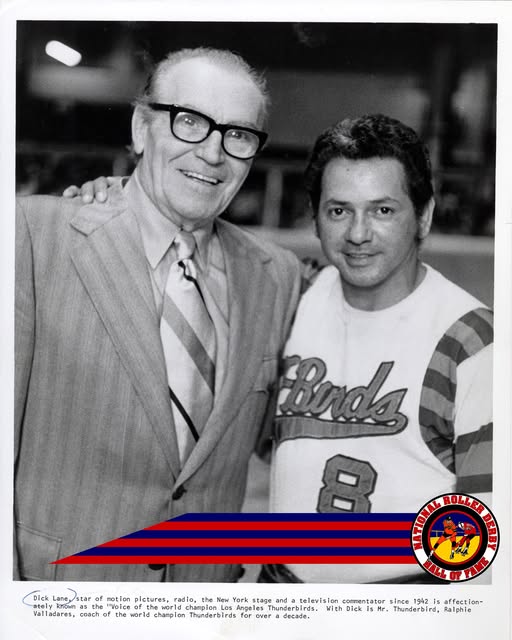

Ralphie Valladares, Los Angeles Braves (1953 to 1959); Los Angeles Thunderbirds (1961 to 1993)

Southern California map pinpoints:

Inglewood, Pico Rivera, Los Angeles (Olympic Auditorium)

In what was a real-deal world of Roller Derby, Ralphie Valladares brought validation, valor and viscosity for those pulling for the underdog. Even a trace of Prince Valiant.

No. 8 wasn’t just gritty great, he could flat-out skate. A lightning-fast play maker for the red, white and blue Los Angeles Thunderbirds, our own very diverse and equally dynamic team of men and women. An abject reflection our city’s inclusive melting pot and blue-color mentality.

It was not a stretch to look back on Valladares as the first high-profile relatable Latino sports star in Los Angeles, some 20 years before Fernando Valenzuela and his mania turned up in the 1980s. At which point in time Valladares was still around to see what kind of magic his sport could squeeze out for this generation at the height of the roller disco scene.

You couldn’t help but buy into the showmanship, and pop culture value, much like an audience would with the Harlem Globetrotters or the Savannah Bananas. There was art, merit and an authentic skill set necessary.

Even kids figured that out if they tried to replicate it on the playground wearing those plastic Dodger give-away batting helmets and hand-me-down four-wheeled skates an older sister might have once worn as a dream to be a figure skater on asphalt, it took talent or else you’d be just another skid mark.

We figured out this was a bit like Three Stooges rough-house theater, cartoons come to life. The merriment of a merry-go-round full of arm whips, flying elbows and heavy pouncing, wrapped up by the theatrics of an obnoxious infield interview and folding-chair throwing, turning over tables in faux anger, was an outlet.

This thing we were captivated by on TV — and at some point, we might have had to adjust tin-foil wrapped TV antennas on the black-and-white Zenith to find the UHF station actually delivering the Sunday night video taped action between 7 and 9 p.m. — also had a scoreboard. A rudimentary graphic popped up full screen to show that what we saw was as important as an MLB or college football game.

Someone was keeping track. We counted on that, too.

For some 50 years, Valladares played the part of player, coach and manager, spanning the 1950s to the early ’90s as the sport kept changing names and venues, something like a medicine show with Dick Lane as the Professor Harold Hill character, barking out the Richmond-9-5171 phone number to lure anyone into the otherwise sketchy Olympic Auditorium in downtrodden downtown L.A.

Lane was also the one screeching all too often: “There goes Little Ralphie Valllladarrezzzzzz on the jam!!”

That was our jam.

And while we all bought in on the statement that Valladares was the sport’s all-time leader in whatever made-up but important numbers they had created — matches played, career points, points scored in a single game, or bruises distributed — the ageless wheelman was all there for its seemingly entire sweet spot of history.

Scott Stephens, a longtime fan, one-time Roller Games skater and author of the 2019 “Rolling Thunder: The Golden Age of Roller Derby & The Rise And Fall of the L.A. T-Birds,” honestly wrote in his book: “Ralphie Valladares was the first and last T-Bird star.”

Yet none of this might have happened if Valladares had his athletic career go the way he thought it was heading. He dreamed of becoming a championship jockey riding thoroughbreds near his home at another famous oval, Hollywood Park. But something rolled him into a much different arena.

Continue reading “No. 8: Ralphie Valladares”