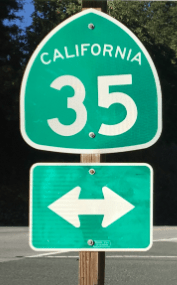

This is the latest post for an ongoing media project — SoCal Sports History 101: The Prime Numbers from 00 to 99 that Uniformly, Uniquely and Unapologetically Reveal The Narrative of Our Region’s Athletic Heritage. Pick a number and highlight an athlete — person, place or thing — most obviously connected to it by fame and fortune, someone who isn’t so obvious, and then take a deeper dive into the most interesting story tied to it. It’s a combination of star power, achievement, longevity, notoriety, and, above all, what makes that athlete so Southern California. Quirkiness and notoriety factor in. And it should open itself to more discussion and debate — which is what sports is best at doing.

The most obvious choices for No. 35:

= Sidney Wicks, UCLA basketball

= Bob Welch, Los Angeles Dodgers

= Cody Bellinger, Los Angeles Dodgers

= Jean-Sebastien Giguere, Anaheim Mighty Ducks

= Christian Okoye, Azusa Pacific College football

The not-so-obvious choices for No. 35:

= Tank Younger, Los Angeles Rams

= Loy Vaught, Los Angeles Clippers

= Rudy LaRusso, Los Angeles Lakers

= Ron Settles, Long Beach State football

The most interesting story for No. 35:

Petros Papadakis, USC football tailback (1996 to 2000)

Southern California map pinpoints:

San Pedro, Palos Verdes, Hollywood, Los Angeles (Coliseum, Sports Arena)

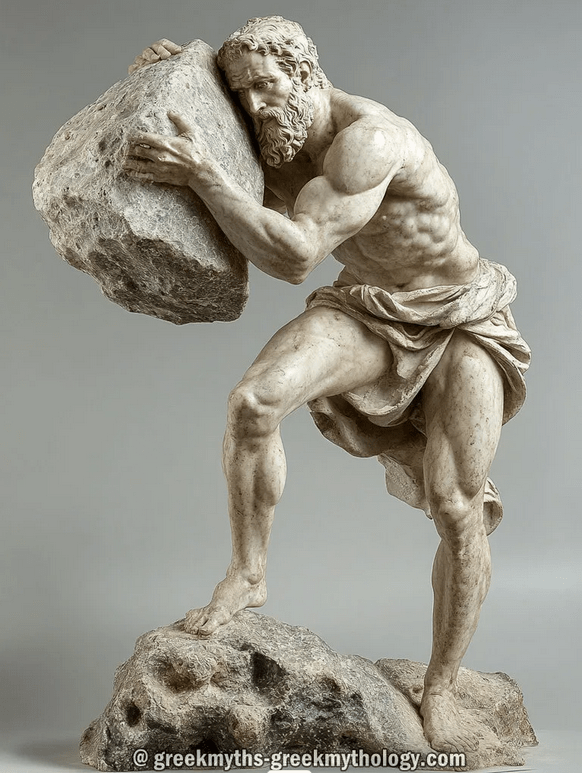

Any sort of perfunctory profile of Petros Papadakis becomes the proverbial Sisyphean pursuit. Hopefully we don’t have to Greek-splain too much here.

Sisyphus, the first king of Ephyra, found his eternal fate in Hades rolling a huge boulder endlessly up a hill, only to see it come back down at him. Every time he made progress and got on a roll, it reversed on him like a Looney Tunes cartoon. The whole thing seemed so Kafkaesque that French philosopher Albert Camus, writing “The Myth of Sisyphus” in 1942, elevated him to some absurd hero status in Greek mythology.

Something that Papadakis might find relatable.

When Papadakis gets on his own a roll, cutting it up on KLAC-AM (570)’s afternoon sports-talk drive-time “Petros and Money Show,” there is far less sports and much more drive to just being a voice for “la raza.” It’s a focus on a feeling of being in “la ciudad” with Papadakis, as familiar as he is bombastic, just the person in the passenger seat making observational conversation to it real.

He is part of USC football legacy, a linage of Cardinal and Gold athletes whose performance has been documented in Los Angeles’ grand Coliseum. Papadakis’ work ethic formed at his family’s famously iconic San Pedro Taverna, as he went from dishwasher to waiter to spending all his earnings for the night back on his guests to make sure they went home happy.

Maybe Papadakis became an accidental broadcaster, but it’s a career that likely defines him as much if not more than anything else. Once a Trojan workhorse in the USC backfield, he is the sometimes-hoarse former Trojan on the dashboard radio. A Red Bull in a china shop of hot topics. The connoisseurs of SoCal sports who enjoy conquering as much as consuming any kind of history lesson are better for it.

Back to the profile: Papadakis has provided quips along the way to make his story even more cohesive:

Continue reading “No. 35: Petros Papadakis”